Chapter 4: Plant Pathology

Chapter Contents

Organisms that cause plant disease can damage plants from the time the seed is put into the ground until the time the crop is harvested and in storage. Some diseases are capable of totally destroying a crop, while others may cause only cosmetic damage. However, cosmetic damage may be equivalent to total destruction in the case of ornamental plants. While many biological entities can cause plant diseases, the vast majority of plant pathogens are fungi.

Plant Diseases in History

Certain diseases have had tremendous impacts on our society. Perhaps one of the most widely known among these is Phytophthora late blight, which caused the potato famine in Ireland (1845). As a result of this epidemic, approximately two million people either starved to death or emigrated, many to the United States.

Grape downy mildew ruined the French wine industry until Bordeaux mixture (a combination of copper sulfate, lime, and water) was accidentally found to control the fungus.

Two forest tree diseases that caused great economic and aesthetic losses in the U.S. are Dutch elm disease and chestnut blight. Both were introduced accidentally to the U.S. Chestnut blight destroyed the most valuable trees in the Appalachians, while Dutch elm disease continues its destruction today. More recently, dogwood anthracnose (which appeared in the 1980s in our area) has caused the long-term prospects of natural dogwood populations in cool, moist locations to become questionable.

These examples are prominent because they caused extensive damage. However, plant diseases cause variable amounts of damage from year to year, depending weather patterns.

Table 4-1: Infectious agents

| Disease Cause | Description | Common Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

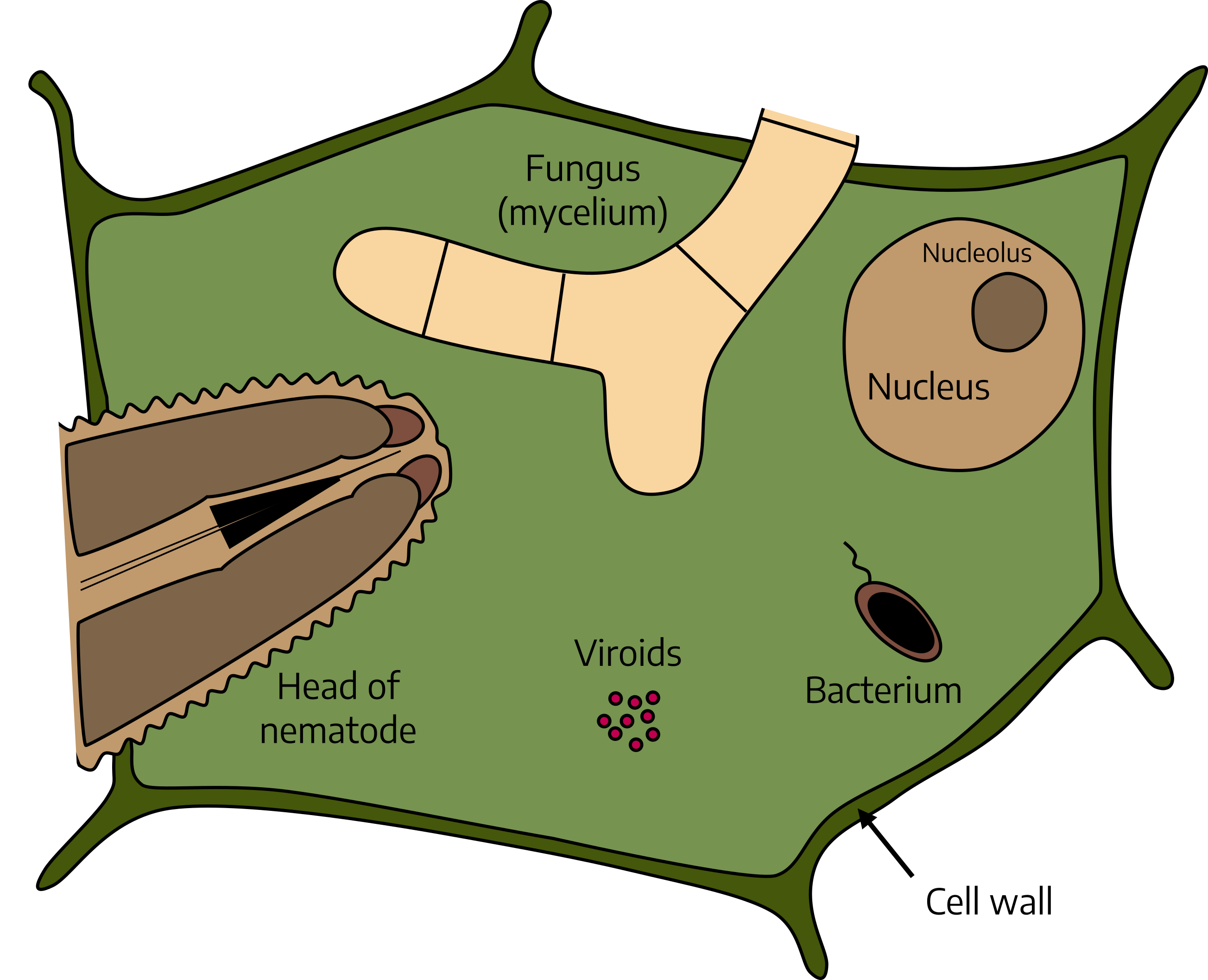

| Fungi | Usually filamentous (threadlike) organisms without chlorophyll. They are the most common causes of plant disease. The fungal filaments usually grow and ramify inside the plant tissue, but may also develop on the surface. Fungi typically reproduce, spread, and persist by minuscule spores. Fungus structures may be visible with the unaided eye (for example, mold, mildew, mushrooms, and conks), or may be microscopically small (for example, many fungi that cause leaf spots). There are thousands of different fungal plant pathogens. | Leaf spots and blights Fruit, stem, root, wood, and seedling rots Cankers Vascular wilts Galls Mildew Rust |

| Bacteria | Minute, one-celled organisms, much smaller and simpler than fungi. Sometimes, large masses of bacterial cells can be visible as bacterial slime or ooze, but more commonly nothing is visible without a microscope. There are several hundred different bacterial plant pathogens. Mycoplasmas or phytoplasmas are specialized bacteria that look like bacteria in the lab, but “behave” more like viruses in the field (for example, they are usually spread by insects and cause symptoms more similar to viruses). | Leaf spots and blights Stem and fruit rot Cankers Galls Vascular wilts |

| Viruses | Infectious molecules (or “clumps” of molecules) that take over plant metabolism and use the plant cell to produce more virus. Several hundred different viruses attack plants. Viroids are similar but even smaller. | Poor growth Mottling and mosaic Ring spots and wavy line patterns Leaf crinkling Distortion |

| Nematodes | A group of nonsegmented roundworms. The fact that these animals are usually covered in plant pathology texts or chapters, while insects and mites are treated separately, is purely an accident of history. Plant-parasitic nematodes are always small (less than 2 millimeters long, usually very thin and thus not easily visible without magnification), and many live in the soil, feeding on roots. A few kinds may live inside leaves or shoots. | Poor root development (and thus poor plant growth and wilt or yellowing) Root galls Swollen root tips Abnormal root branching |

Diseases Defined: Cause of Disease

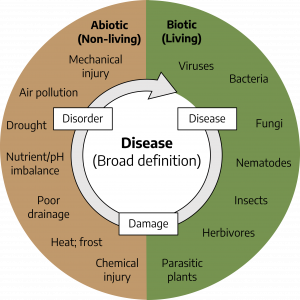

A plant disease may be defined as any disturbance that prevents the normal development of a plant and reduces its economic or aesthetic value. Plant disease is the rule rather than the exception. Every plant has disease problems of one sort or another. Fortunately, plants either tolerate these maladies, or the maladies are not very serious in most years. According to this broad definition, plant disease is caused by a large array of biotic (living) agents such as fungi, nematodes, bacteria, and viruses; by a large array of abiotic (nonliving) factors such as nutrient deficiencies and water or temperature stress; or sometimes by a combination or complex of these factors (Figure 4-1). Terms such as “disorder” and “damage” are often used to refer to abiotic problems, whereas the term “disease” is used to refer to biotic problems, but the boundaries are indistinct.

Steps to Disease Diagnosis

See Chapter 6 “Diagnosing Plant Damage” for more details.

- Study the symptoms and signs; together, they form the disease syndrome. Symptoms are physical expressions of disease in the host tissue, e.g., changes in color, appearance, integrity, etc. Primary symptoms are symptoms at the point where the pathogen is active. Secondary symptoms are the result of pathogen activity somewhere else in the plant. For example, if a fungus invaded the roots of a plant, the resulting root rot is the primary symptom; the above-ground symptoms of poor growth, leaf yellowing, wilting, etc., are secondary symptoms. For correct diagnosis it is very important to find the primary symptoms, because it’s only there that the pathogen can be found. A lesion is a well-defined area of diseased or injured tissue, often dead spots or areas. Lesions are often a primary symptom. Signs are structures or products of the pathogen itself on a host plant. Examples of signs are mold, fungal fruiting bodies, and bacterial slime/ooze. Examination with a hand lens may sometimes reveal structures that can aid in diagnosis. Placing the plant sample in a moist chamber (closed container or plastic bag) for a day or two may stimulate production of such structures. The presence of tiny, pimple-like, dark fruiting bodies in the spot indicate the presence of a fungus and may provide sufficient information for diagnosing the disease.

- Collect background information on the history of and patterns in the problem’s development. For instance, the cause of sudden death of shoot tips is more easily diagnosed once one realizes that a night frost has occurred a few days earlier. If identical symptoms develop on several different species of plants, it is highly likely that the cause is abiotic (for instance, herbicide damage). The diagnostic form used by Virginia Cooperative Extension requires much information that may be helpful in diagnosis, but one should always be on the lookout for additional clues.

- Consult reference books and the internet to compare syndromes with descriptions and pictures. Keep in mind that not all possible problems may be described or pictured in books, especially non plant-specific abiotic problems, which may be omitted. Be aware that not all web sites have been carefully reviewed by professional plant pathologists.

- Narrow down the possibilities by searching online for research-based information. Try adding “site:edu” to the end of your search query to see results from universities, or go to the Extension search page. Refer to a lab for further testing if the diagnosis in unclear.

The Plant Disease Clinic at Virginia Tech is a wonderful resource for assistance with diagnostic problems and staying informed about diseases in Virginia.

Watch: Plant Disease Clinic: Digital Diagnosis and Preparing Samples with Elizabeth Bush and Mary Ann Hansen

Symptoms (Change in Plant Appearance) of Plant Disease

Chlorosis

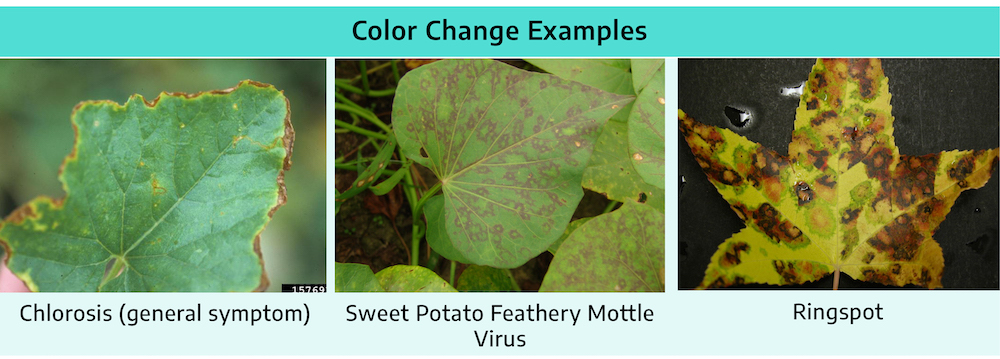

Chlorosis is the yellowing of normally green tissue. Pattern of the discoloration may be helpful in diagnosis

- General Chlorosis: Yellowing of entire leaf or plant. Causes: Nutrient deficiencies, root problems, nematodes

- Interveinal Chlorosis: Yelllowing of the leaf tissue between veins while the veins themselves remain green. Causes: Poor root functioning, root rot, nematodes, nutrient deficiencies, improper pH, chemical injury

- Chlorosis along the Veins: Chlorotic areas along the veins. Causes: Viruses, some herbicides

- Marginal Chlorosis: Yellowing of leaf edges. Causes: Chemical injury, nutrient toxicity

- Mosaic, mottle: Irregular light and dark green areas on the leaves, with distinct (mosaic) or less distinct (mottle) margins. Chlorotic areas may be on or between veins, pattern is more random on or between veins, pattern is more random than for interveinal chlorosis. Causes: Commonly virus, sometimes genetic abnormality, some nutrient deficiencies (esp. mottle)

- Ringspot: A circular area of chlorosis or necrosis with a green center. Causes: Viruses, cold weather (African violet)

- Line Patterns: Irregular patterns or wavy lines; on some plants lines may form a more regular pattern in the outline of an oak leaf. Causes: Viruses, chemical injury

Other Color Changes

- Color Breaking: Abnormal streaks of different color in colored plant organs (usually flowers). Causes: Virus, genetic (streaks usually more regular if genetic than with virus)

- Purpling, Reddening: Development of abnormal purple or red colors in normally green tissue. Causes: Phosphorus or boron deficiency, some herbicides, cold temperatures

- Bronzing: Foliage takes on gold or copper metallic appearance. Causes: Insects, mites, cold injury

- Browning: Plant tissue turns brown and may also become dry and brittle. Usually associated with tissue death. Browning is sometimes diagnostic, as with vascular browning in vascular plants. Causes: Many

- Russeting: Superficial roughening of plant epidermis (surface tissue) (e.g., apple) due to cork formation. Causes: Some fungal diseases (e.g., powdery mildew), frost injury, some chemicals, nematodes (e.g., root knot on potato tubers)

Necrosis (Tissue Death)

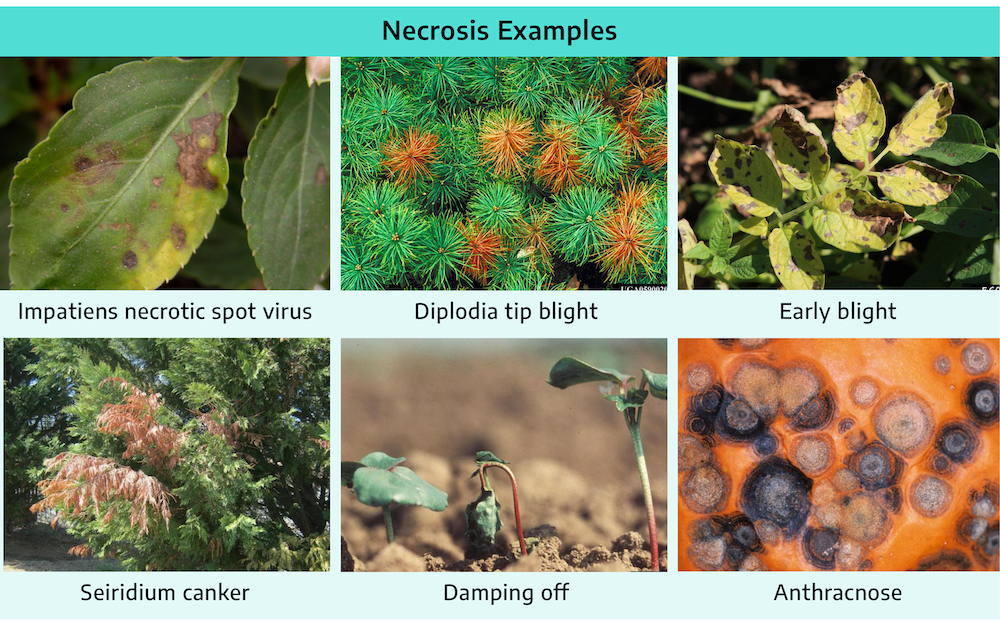

- Spot: Distinct necrotic areas on leaves and superficial lesions on fruits and herbaceous stems. May be round, angular, or irregular; they may have concentric rings or be surrounded by purple rims or chlorotic haloes. Commonly caused by fungi, but can also be caused by bacteria and abiotic factors (e.g., paraquat drift), uncommonly caused by viruses or nematodes.

- Blight: A general killing of plant parts (twigs, limbs, leaves, flowers, or shoots). Sometimes called Blast. May be primary or secondary symptom, for example, due to root disease or a canker girdling a stem or trunk. Causes: Many

- Blotch: Large, superficially discolored areas of irregular shape on leaves, shoots, fruits, and stems. Causes: Fungi, bacteria, chemical injury, sun scald

- Scorch, Marginal Necrosis: “Burning” of leaf margins. Causes: Drought, excess salt or fertilizer, root problems, cankers, vascular fungi, bacteria

- Rot: Affected tissues discolored, disintegrated (decayed), and often softened. Examples: wood rot (fungal), root rot (usually fungal), and soft rot (bacterial). Causes: Fungi, bacteria

- Canker: Necrotic areas in the bark of woody or herbaceous stems or twigs. Surfaces may be smooth or rough, sunken with raised margins, or swollen and cracked. Raised margins may sometimes have concentric rings = target shape. Causes: Usually fungi, bacteria

- Damping-Off: Seed, seedling rot, or canker-like lesions girdling seedlings and young herbaceous plants at the ground-line that cause the seedling to fall over and rot. Seedling death before emerging above ground is pre-emergence damping off. Seedling death after emergence is called post-emergence damping off. Causes: Usually fungi, sometimes insects, or soil conditions

- Shot-Hole: Dead areas of leaf spots fall away leaving holes in the leaves. Leaves may have tattered appearance if holes are numerous. Holes may be irregular in shape. Causes: Fungi, bacteria, insect-feeding

- Dieback: Twigs, limbs, or shoots die from the tip back. Similar to, if not the same as, blight. Causes: See blight

- Anthracnose: Disease caused by a certain group of fungi that produce acervuli (a type of fruiting body — a small blister on the lesion surface which in moist area may become pink from spore masses). Symptoms may vary from leaf spots to fruit or twig lesions. Causes: Fungi (per definition)

- Water-Soaked Appearance: Translucent appearance of tissue due to the intercellular spaces being filled with water. Often the first visible symptom of cell death. Causes: Bacteria, fungi, frost injury

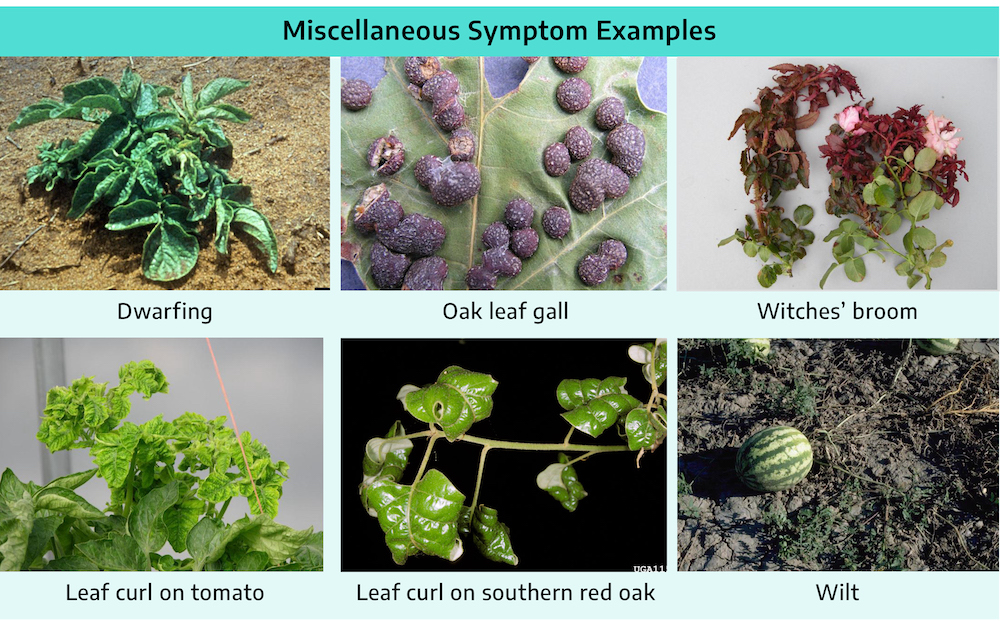

Miscellaneous Symptoms

- Dwarfing, Stunting: Failure of a plant part or whole plant to attain normal size. Causes: Many

- Gall, Tumor, Knot: Localized enlargement of plant parts. Examples: root gall, crown gall, leaf gall. Causes: Some fungi, some bacteria, some viruses, some nematodes (roots), MANY insects and mites

- Witches’ Broom: A dense, broom-like clustering of branches resulting from development of numerous adventitious buds at one region. Causes: Fungi, phytoplasmas, some mites

- Leaf Curl: Leaf curl is due to irregular growth; parts grow excessively or growth of parts is retarded compared to the rest of the leaf blade. Causes: Viruses, some fungi, herbicides, ethylene, aphids

- Wilt: Plant parts limp from lack of water. Causes: Drought, root rot, root damage from nematodes, other root problems, vascular pathogens (fungi, bacteria), walnut toxicity

- Leaf drop, Abscission: Falling off of leaves, flowers, fruit, or other tissues. Causes: Leaf spot pathogens, root pathogens, growth regulators, various abiotic conditions

- Epinasty: Downward curvature of leaves due to abnormal growth in part of the petiole. Causes: Vascular wilt pathogens, ethylene injury, some herbicides

- Gummosis: Production and exudation of a thick gummy liquid in response to injury or disease. Causes: Insects, fungal or bacterial infection, normal plant response to injury (e.g., in Prunus species)

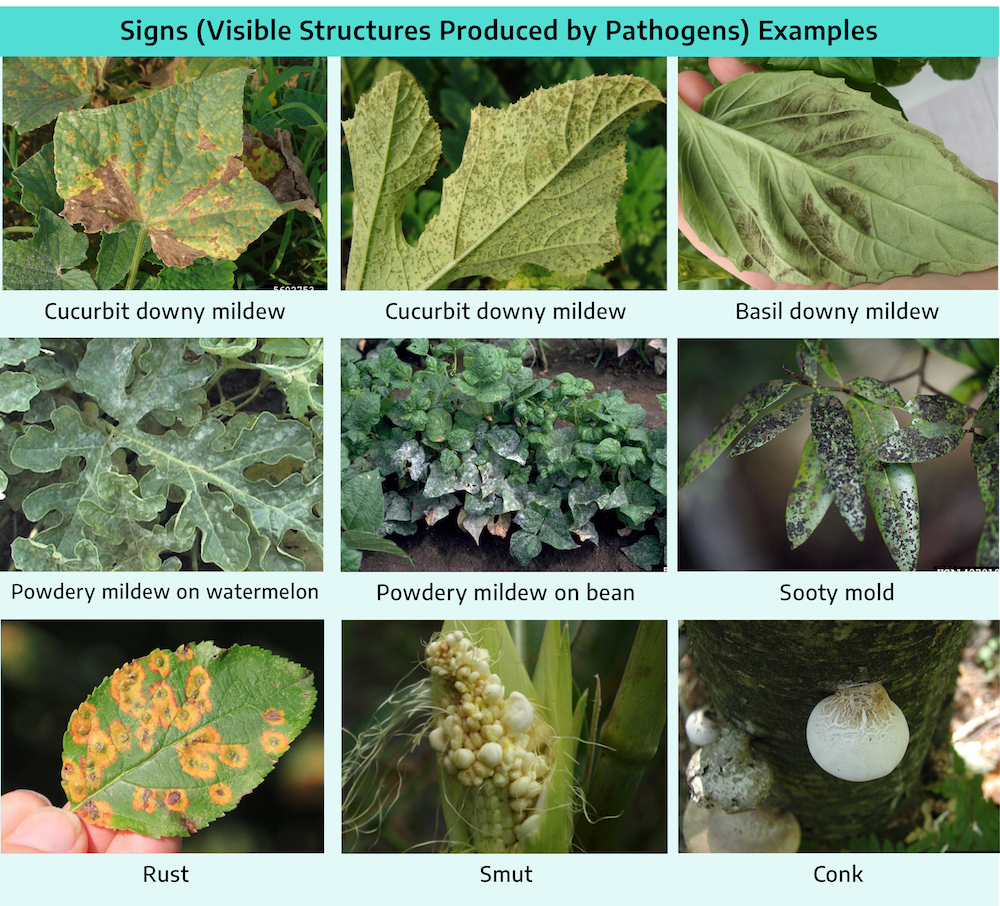

Signs (Visible Structures Produced by Pathogens) of Plant Disease

- Mildew: Grayish or whitish growth of fungus, of two groups: downy mildew, (grayish, often on lower leaf surface) and powdery mildew (whitish, on both upper and lower leaf surfaces – the most common). The names reflect the appearance; the two groups are quite different in their biology.

- Mold: Fungus mycelium and/or fruiting structures, similar to mildew but of different groups of fungi. Molds may be many colors, commonly gray, white, black, blue, or green.

- Sooty Mold: Black fungal growth on plant surface which can be scraped off. Caused by dark-colored fungi that grow on sticky secretions of sucking insects, such as aphids, whiteflies, and scale insects. Sooty mold fungi do not infect the plant itself.

- Rust: Spore pustules of a certain group of fungi called the rust fungi (sometimes also orange leaf spots and galls or cankers). Color of pustules may be yellow, orange, red, brown, or black.

- Smut: Spore masses of a certain group of fungi called the smut fungi, usually brown or black and powdery. May occur in inflorescences (for example wheat loose smut, corn smut), leaves (stripe smut of grasses), sometimes on stems (corn smut galls).

- Mushroom: Large fruiting body of certain fungi, few are plant pathogens, most are secondary decay organisms.

- Conk: Large, woody, shelf-like fruiting body of many of the wood decay fungi

- Bacterial Slime: Drops of sap containing bacteria. Found on the surface of plants infected by bacteria, or Slime especially under humid conditions.

Disease Development

Development and severity of disease is determined by three conditions. First, it is necessary to have a susceptible host plant. Each species of plant is capable of being infected by only certain pathogens. The plant must be in a stage of development susceptible to infection by the disease agent. The second requirement is the presence of an active pathogen in a stage of development conducive to infecting the host plant. If there is no or little inoculum of the pathogen present, there can be no or only a little disease. The third condition is an environment suitable for the pathogen to infect the plant. Temperature and moisture are important factors.

Disease Cycle

The chain of events involved in disease development is the disease cycle, which summarizes answers to questions such as:

- What are sources and forms of inoculum? (Inoculum is part of a pathogen that can cause infection). Possibilities include: other infected plants, plant materials (for example, seed, tubers, cuttings, and transplants), plant debris (dead leaves, stems, and roots) from infected plants, or infested soil.

- When or under what conditions does the pathogen infect? (Infection means to become established on/in the plant and initiate disease development). For example, most fungi and bacteria that cause leaf spots and blights can infect only when leaves are wet. Some of these pathogens may infect only young, developing leaves, while others infect only old, senescent leaves.

- How long does it take for the pathogen to colonize the plant and for symptoms to develop? This may range from a few days to a few weeks or sometimes months. During this stage, although symptoms do not yet show, it is often already too late to prevent a problem.

- After how long and under what conditions does the pathogen reproduce? Fungi and bacteria often need high humidity to produce more inoculum.

- How and under what conditions does the pathogen spread? Means of dispersal include: wind, water drip and splash, soil, anything that moves soil (e.g. shoes), running water (run-off, irrigation water), vectors (for example, aphids for many virus diseases, beetles for Dutch elm disease), equipment, tools, and moving plants from one location to another.

- How and where does the pathogen survive adverse conditions (for example, winter, dry spell, period of absence of host)? See above under sources of inoculum. Some pathogens produce specialized structures that are highly resistant to extremes in temperature or moisture (e.g. sclerotia of the fungus that causes southern blight).

Methods and Tools to Control Diseases

Cultural Practices to Control Diseases

Plant only certified-as-disease-free seed or planting stock

- Certified seed is only free of those diseases for which it has been tested ! Quality depends on the program.

- General nursery inspection program — tries to make sure that only materials free of (important) diseases and pests are sold.

Sanitation

- Removal of diseased plants or plant parts (pruning, roguing).

- Removal and/or destruction of plant debris and leaf litter that may contain inoculum.

- Removal of other hosts (including weeds) of the pathogen.

- Prevention of introduction and spread of pathogens: clean tools, equipment, clothes, etc.

Importance of disinfecting tools to prevent spread of plant disease

By Mary Ann Hansen, Extension Plant Pathologist, Virginia Tech

One way to help prevent the spread of some plant diseases is to sanitize garden tools before using them on healthy plants. This is especially important for preventing diseases that can be transmitted from diseased plant tissue to healthy plant tissue.

A good example of a disease for which sanitizing tools is especially important is boxwood blight. If infested plant debris remains on pruning shears after being used on a diseased plant, the disease could be transmitted to the next stem that is pruned with the shears. To sanitize tools effectively, it is important first to wash any visible plant debris from the surface of the tool before treating it with the sanitizer.

The tool should either be sprayed with the sanitizer and allowed to air dry or dipped in the sanitizer for the recommended length of time. Wiping tools with sanitizing wipes is NOT an effective way to sanitize a tool! Some readily available sanitizers include ethanol (70% or greater), sodium hypochlorite (a 1:14 solution of 8.25% household bleach), and Lysol Brand Concentrate Disinfectant. (Bleach can be corrosive to tools, so remember to rinse tools well after sanitizing them with bleach.)

There are also commercial sanitizer products labeled for use by professional applicators. Since sanitizing tools can be time-consuming in the home garden, try, at a minimum, to sanitize tools before moving to a new plant and/or location. More detail on appropriate use of sanitizers for preventing spread of boxwood blight can be found on the Virginia Boxwood Blight Task Force website.

Tillage and cultivation

- Buries plant debris with inoculum, leads to faster degradation.

- May also bring inoculum to the surface where it is exposed to sun and drying cycles.

Crop rotation

- Rotation with a species of plant that is not a host for a particular pathogen prevents buildup of that pathogen over the years, and allows inoculum to decline due to natural causes.

Temperature management (make it optimum for crop, but unfavorable for pathogen)

- Direct: greenhouse, storage facilities.

- Indirect: shading, mulching to affect soil temperature, timing of planting (planting warm-season crops into cold soils may predispose them to damping-off diseases), solarization.

Moisture management (make conditions less favorable for pathogen)

- Irrigation: Furrow and flood irrigation may spread pathogens and may saturate soil, which promotes some root diseases. Sprinkler irrigation may lead to splash dispersal of pathogens, and makes the leaves wet, creating conditions favorable for infection by many leaf pathogens. Timing may be important (late afternoon may be bad – leads to long periods of leaf wetness). To prevent pathogen dispersal and leaf wetness, it is usually best to water at the base of the plant, if possible. Drip irrigation reduces chances of spreading pathogens and creating conditions favorable for disease.

- Drainage: Avoid planting in poorly drained areas or choose plants that are adapted to wet sites. Install drainage tile before planting in poorly drained soil. Plant on raised beds to allow water to drain away from the roots.

- Relative humidity: Direct management: greenhouse, storage facilities. Indirect management: pruning and thinning for better canopy ventilation; foliar diseases tend to be more severe in shaded areas because the leaves stay wet longer.

- Management of fertilization and soil pH: Some diseases are worse when fertilization is excessive; others are worse when fertility is poor. Some diseases are favored by acid soil, others by alkaline soil.

- Soil amendments and mulches: Organic matter may stimulate soil microbial activity that may inhibit growth of pathogens. Adding organic matter can also help to improve drainage.

- Repel or control vectors: For example, by insecticides or by placing reflective aluminum foil around young plants to repel aphids.

- Plant at proper planting depth: Roots may not get enough oxygen or the crown may rot when plants are too deep.

- Avoid injury, which can invite decay organisms.

A program approach to control diseases

Plant disease control has never placed sole reliance on chemicals. Other major pillars are cultural practices and resistant cultivars. The use of several simultaneous control practices is usually required for effective disease management. A combination of methods is always required to manage the numerous diseases (Integrated Disease Management) and other pests (Integrated Pest Management) that threaten a specific garden or landscape.

A complete program for an annual plant might include the following steps (with modifications for establishment of perennial plants):

- Assess inoculum based on experience from past years. Identify possible sources.

- Use cultural practices or treatments that reduce inoculum. For example:

- Rotate out of susceptible crop

- Eradicate reservoir hosts (weeds, etc.)

- Remove or bury infested or diseased plant debris

- Steam or bleach (e.g., pots, flats, soil, tools)

- Select top-quality seed or planting stock that is:

- Adapted to the area and site

- Disease-free (from a reputable source)

- Disease-resistant (Note that few plants are resistant to all diseases; choose plants that are resistant to the diseases that have been previously diagnosed in that plant)

- Purchase treated seed (fungicide/insecticide) if experience shows it is needed.

Plant at optimum time, row spacing, and seeding rate; apply fertilizer and pesticide treatments as needed. - Monitor plants for early detection of disease problems:

- Get an accurate diagnosis of the problem. County Extension personnel can provide advice or forward sample to a lab for diagnosis.

- Apply chemicals as needed. Most sprays are PREVENTATIVE.

- Cultural practices — e.g., canopy management

- Harvest at proper time; handle and store produce properly.

- Remove and destroy plant debris to reduce survival of pathogens. Do not compost weeds or diseased plant material – place in trash.

- Plan for next year. Take steps to prevent future problems (rotations, etc.). Keep accurate records and maps that show pest and disease problems.

Plant Resistance to Control Diseases

- Genetically resistant cultivars may be partially resistant (some disease develops; nevertheless, these plants can be very useful) or completely resistant to a particular disease (but not necessarily to other diseases).

- Genetic resistance may be defeated when a pathogen develops new strains that can attack the resistant cultivars. Resistance may also sometimes “break down” when plant is under excessive stress, or when several pathogens attack at the same time.

- “Physiological” resistance refers to reducing the susceptibility of the plant by management of water, nutrients, light, and other cultural practices.

Chemical Controls

Regulatory Practices to Control Diseases

- Quarantine laws and inspections at the borders to keep foreign pathogens out.

- Certification of seed and planting stock to minimize initial inoculum.

Control of Diseases: Avoiding Attack

Keep host and pathogen out of striking distance from each other by:

- Exclusion – keep pathogen away from the crop.

- Keep pathogen out of the country, state. Quarantine regulations ban importation of certain types of plant material; other kinds of plant material must be inspected before being admitted.

- Keep pathogen out of the garden. Avoid spread of contaminated soil, equipment, boots, irrigation water, etc. Use pathogen-free planting material.

- Avoidance or evasion – keep plants away from the pathogen.

- Do not plant in already infested sites or in areas where the pathogen is a major problem.

- Grow plants in areas, during times, and under conditions that are not favorable for pathogen development. Reduce or eradicate inoculum. Complete eradication of a pathogen from an area or a country is rare.

- Reduction of inoculum by sanitation, deep plowing, crop rotation, etc., is common and often effective.

- Protect plants by reducing or eliminating chances for infection (using both cultural and chemical protection).

- Plant resistant plants (another way to protect the plant).

Physical Methods to Control Diseases

- Soil treatment with steam to eliminate pathogens, weed seeds, and insects. This is done mostly in greenhouses and seedbeds; it is not very practical for homeowners.

- Soil “solarization” in warm climates during the hot season by covering soil for several weeks with clear plastic. High temperatures eliminate many pathogens and weeds. This is most effective in tropical or subtropical areas where there is a long period of continuous sunlight and high temperatures.

- Hot-water treatment of seed and planting stock (not very practical for homeowners).

Biological Control

- Apply organisms that inhibit, eat, or parasitize plant pathogens. Currently, there are only a few commercially available examples of this available for home use.

- Stimulate naturally occurring beneficial organisms by organic soil amendments, water management, etc.

Summary

Plant diseases are to be expected. Fortunately, in most years there are few truly devastating diseases.

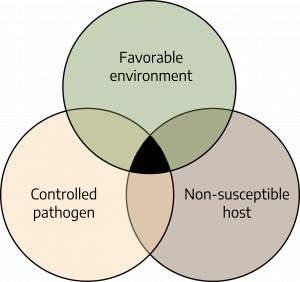

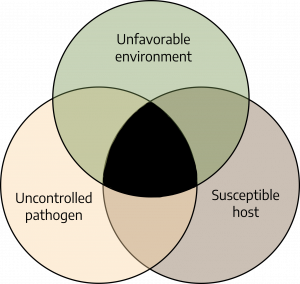

For disease to occur, there must be a susceptible host, a suitable environment, and a living pathogen. When all three conditions are met, disease occurs. Severity of the disease depends on the degree to which the conditions are met.

Diagnosis depends on a careful evaluation of symptoms, but also on evaluation of the history and patterns of disease development.

Disease control involves more than the use of chemicals. Planting resistant cultivars, destruction of inoculum sources, and a variety of cultural practices should be considered first. A combination of control methods, based on understanding of the biology of the pathogen, will give best results.

Additional Resources

Attributions

- Sherry Kern, Virginia Beach Extension Master Gardener (2021 reviser)

- Adria C. Bordas, Extension Agent, Agriculture and Natural Resources (2015 reviser)

- Mary Ann Hansen, Department of Plant Pathology, Physiology, and Weed Science (2015 reviewer)

- Anton Baudoin, Department of Plant Pathology, Physiology, and Weed Science (2009 reviser)

- Mary Ann Hansen, Department of Plant Pathology, Physiology, and Weed Science (2009 reviser)

Image Attributions

- Figure 4-1: Abiotic and biotic causes of plant diseases. Grey, Kindred. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- Figure 4-2: Schematic diagram of the shapes and sizes of certain plant pathogens in relation to a plant cell. Grey, Kindred. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- Figure 4-3: Marginal necrosis and chlorosis on cantaloupe, Sweet Potato Feathery Mottle Virus (Potyvirus SPFMV)on sweet potato, Ringspot caused by Mycosphaerella brassicicola. Johnson, Devon. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Includes image 5605913 by Gerald Holmes from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 1576917 by Gerald Holmes from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), and image 5549138 by Penn State Department of Plant Pathology & Environmental Microbiology Archives from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US).

- Figure 4-4: Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV) (Tospovirus INSV) on touch-me-not (Impatiens spp. L.), Diplodia tip blights (Diplodia spp. Fr.), early blight (Alternaria solani) on potato, Seiridium cankers (Seiridium sp.), damping off (general) on cotton, anthracnose (Colletotrichum orbiculare) on pumpkin surface. Johnson, Devon. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Includes image 5549122 by Penn State Department of Plant Pathology & Environmental Microbiology Archives from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 0590020 by Robert L. Anderson from Bugwood.org CC BY 3.0 US), image 5606707 by Gerald Holmes from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 5435276 by Jennifer Olson from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 1572331 by Gerald Holmes from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), and image 1576761 by Gerald Holmes from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US).

- Figure 4-5: Dwarfing caused by potato yellow dwarf virus on potato, oak leaf gall (Polystepha pilulae), witches’ brooming caused by rose rosette disease (RRD) (Emaravirus RRD) on rose, leaf curl caused by tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) (Begomovirus TYLCV) on tomato, aphid induced leaf curl on southern red oak (Quercus falcata Michx.), melon plants showing Fusarium wilt infection caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Johnson, Devon. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Includes image 0162085 by American Phytopathological Society from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 5507614 by Bruce Watt from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 5485808 by Mary Ann Hansen from Bugwood.org (CC BY 3.0 US), image 5411469 by Don Ferrin from Bugwood.org (CC BY 3.0 US), image 1150004 by Andrew J. Boone from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), and image 5365875 by Howard F. Schwartz from Bugwood.org (CC BY 3.0 US).

- Figure 4-6: Cucumber foliage showing symptoms of cucurbit downy mildew (Pseudoperonospora cubensis), pumpkin foliage showing symptoms of cucurbit downy mildew (Pseudoperonospora cubensis), basil downy mildew (Peronospora belbahrii) on underside of basil leaf, powdery mildew (Podosphaera fuliginea) on watermelon leaf, powdery mildew (Erysiphe polygoni) infection of bean plants, sooty mold on California laurel, cedar apple rust disease (Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae) on apple tree, corn smut (Mycosarcoma maydis) on corn cob, young birch conk (Piptoporus betulinus). Johnson, Devon. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Includes image 5602753 by Gerald Holmes from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 5602737 by Gerald Holmes from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 5551704 by Rebecca A. Melanson from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 5077043 by David B. Langston from Bugwood.org (CC BY 3.0 US), image 5358902 by Howard F. Schwartz from Bugwood.org (CC BY 3.0 US), image 1427010 by Joseph OBrien from Bugwood.org (CC BY 3.0 US), image 5486242 by James Chatfield from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), image 5604984 by Daren Mueller from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), and image 2187099 by Joseph LaForest from Bugwood.org (CC BY-NC 3.0 US).

- Figure 4-7: Slight disease. Grey, Kindred. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- Figure 4-8: Severe disease. Grey, Kindred. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- Figure 4-9: Pruning tools soaking in a 1:14 household bleach solution. Johnson, Devon. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Living agents such as fungi, nematodes, bacteria, and viruses

Nonliving factors such as nutrient deficiencies and water or temperature stress

Physical expressions of disease in the host tissue, e.g., changes in color, appearance, integrity, etc.

A well defined area of diseased or injured tissue, often dead spots or areas. Lesions are often a primary symptom.

Structures or products of the pathogen itself on a host plant, for example, mold, fungal fruiting bodies, or bacterial slime/ooze

Yellowing of normally green tissue

A plant that another organism (such as an insect or virus) lives on

Part of a pathogen that can cause infection

To become established on/in the plant and initiate disease development

Methods that involve growing and maintaining healthy plants without using synthetic (manmade) fertilizers, pesticides, hormones, and other materials