Chapter 19: Virginia Native Plants

Chapter Contents

- 8 Reasons to Plant Native Plants

- Virginia’s History of Native Plants

- What is a Native Plant?

- Native Plants Outside of Academia

- Natives: Why Now?

- The Flora of Virginia

- Choosing Native Plants to Match Your Site

- Going Native, but to What Degree?

- Why Are Native Plants Important?

- Virginia Invasives: 8 More Reasons to Plant Native Plants

- Additional Resources

If you’re becoming an Extension Master Gardener, you almost certainly are aware of native plants. If you’ve feasted your eyes on the fall foliage on the Skyline Drive, gasped at the beauty of the white trilliums and other spring ephemerals at the G. Richard Thompson Wildlife Management Area in Fauquier, Warren, and Clarke counties, walked the Nancy Larrick Crosby Native Plant Trail at Blandy Experimental Farm at the State Arboretum of Virginia in Boyce, or spent time any of the many national and state parks and forests and natural area preserves, you have hit upon some prime viewing area for plants native to Virginia.

Chances are, you also know what sets native plants apart. You know they are part of Virginia’s history, its cultural and natural heritage, and its native ecology. You understand that those special plant-viewing sites are set aside in response to an array of threats to Virginia native plants and habitats, and it wouldn’t be surprising if you wanted to make sure you had natives in your own garden or landscape.

Using natives doesn’t only incorporate the wonder of having them around us. In selecting natives for spaces and places and in ensuring before purchase that their needs will be met at the place planned, you make a biological connection with and a commitment to the plants, natural communities, interactions, and ecology. It truly is conservation in action, whatever the degree of “going native.” In light of habitat destruction and the climate crisis, when you use native plants, you help meet the needs of native animals, from insects and other invertebrates to birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. You provide habitat and can help reconnect natural lands that have been severed from one another as humans have cleared land for myriad purposes. In using native plants, you can replace or repair some of what has been lost or damaged and help it look great at the same time. As you envision a bright future for native plants, you feel the momentum of this change and that you are on the cusp of a time when even larger commercial nurseries will prominently label and display native plants, getting them to a larger, more aware market.

Before you select plants, explore the meaning of native plant. Learn about the study of Virginia natives, how to find out what is native to Virginia and specific counties, and which plants might best suit your own piece of Virginia.

8 Reasons to Plant Native Plants

1. They’re beautiful and can often be substituted for nonnative standbys.

Native plants are beautiful and can give the effects wanted in home gardens, yards, or landscapes, or in those of a client or project leader. The design can be as formal or as natural as desired, as long as the plants’ needs are met, just as is done with the nonnative plants commonly used. The slightly fragrant wild azalea, or pinxterflower (Rhododendron periclymenoides), is a great choice for the azalea slot in the moister parts of a yard, and it’s native to all but Virginia’s four westernmost counties.

2. They’re adapted to the native climate.

It may be self-evident, but it’s still worth pointing out that native plants evolved in the places to which they are native, so they’re better adapted to those conditions, such as rainfall and temperature, than are many garden-variety nonnatives, requiring less watering and other subsidies.

3. They provide food and habitat for native animals with which they evolved.

Oak trees (Quercus spp.) are the main host of the oak treehopper, Platycotis vitata, a true bug. While the treehopper relies on the oak, birds and insectivorous insects prey on the leafhoppers. Therefore oak trees support the ecosystem, providing food for leafhoppers which in turn provide food for our native bird population.

4. They’re part of Virginia’s natural heritage.

The wild turkey —first runner-up for national bird—has come back from dangerously low populations little more than a decade ago. Not so strictly allied to a type of plant as is the oak treehopper, turkeys do best in a mixed-hardwood forest that promises lots of acorns, nuts, and fruits, with some younger trees and shrubs for cover.

5. They can bridge fragments of natural habitats.

Natives are the choice for restoring sites such as salt marshes and areas disturbed by construction. When used in the yard, they aren’t just landscaping; they’re helping heal over natural habitats fragmented by the usual human activities of home and road building and achieving a larger contiguous expanse that appeals more to native animals. If you need to replace a fallen nonnative tree, consider planting a white oak (Quercus alba), native to every Virginia county. Oaks provide habitat and food for many, many animals, from herbivores to birds feeding nestlings to acorn-eaters.

6. They introduce us to a new set of like-minded folks.

Native plants bring together like-minded people interested in horticulture and the environment. There are many ways to get involved, including joining groups like the Extension Master Gardener program or Master Naturalists, which offer programming and volunteer opportunities to expand awareness of and access to Virginia native plants. Attend meetings, programs, workshops, native-plant sales, and field trips. Learn from one other!

7. They fit in with organic and thrifty gardening.

In growing native plants, gardeners use few if any pesticides and chemical fertilizers. If plants are matched to the right sites, water is rarely needed after the first season as the plants get established. Native plants that replace traditional lawns require no mowing, resulting in less noise, less exhaust, and less runoff. That helps everybody, from our neighbors to the pollinators and other inhabitants of the ecosystem.

8. They reconnect gardening with ecology.

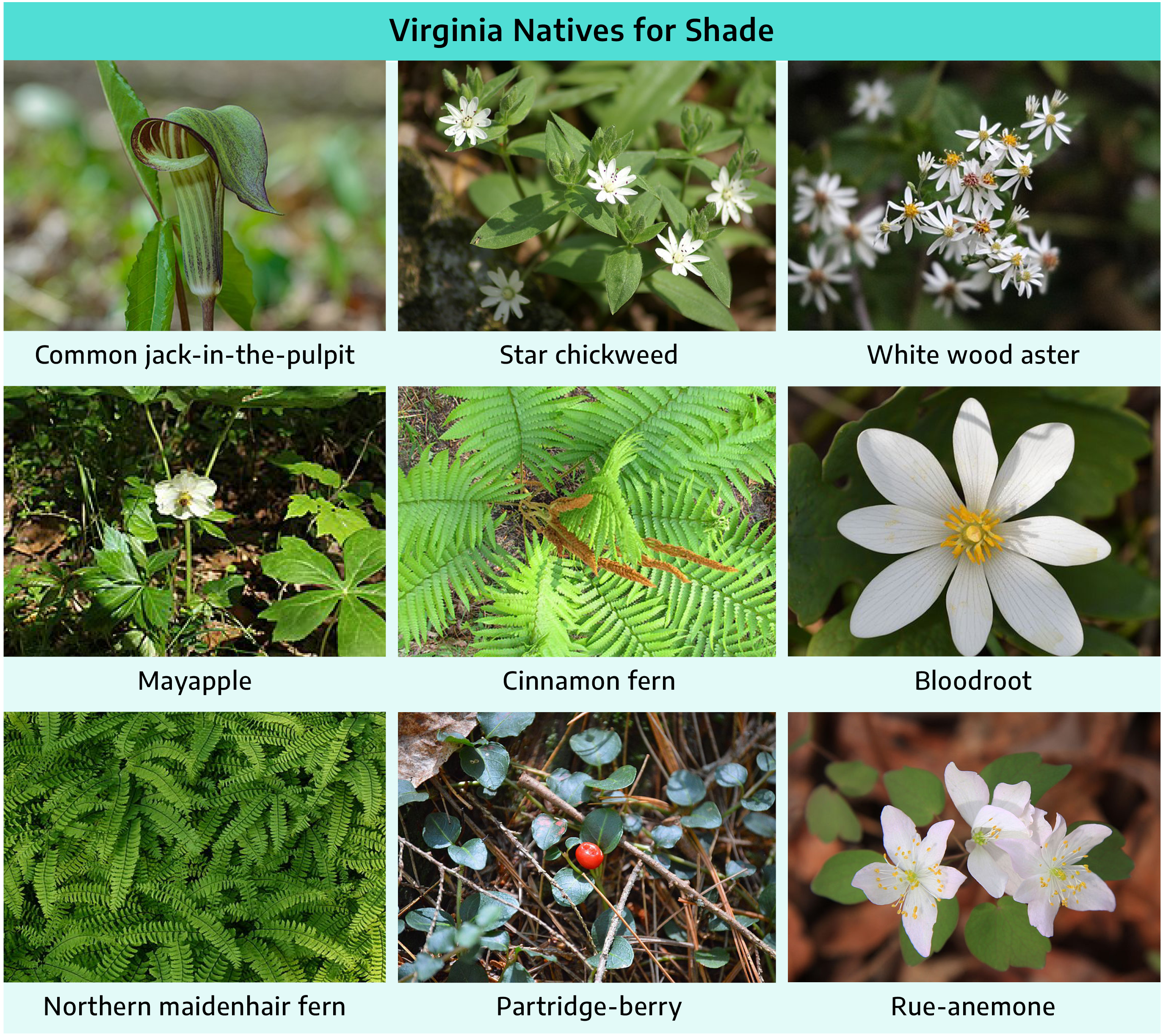

You know almost innately not to plant tender, water-loving plants in full sun on gravel and not to plant annual sunflowers in a secluded, shady nook in your yard. Natives have needs too, and one must consider what kind of habitats a site provides, such as moisture, sunlight, and soil, to pick plants that are a good fit for such spots. Forcing them to try to make do in a less than ideal place is rarely successful without a lot of constant care. If you’re planting the white wood aster (Eurybia divaricata), the ecology’s in the name: give it a semi-shady to shady, maybe woodsy, spot for best results.

Virginia’s History of Native Plants

Virginians have always been aware of native plants. Indigenous peoples knew them inside and out, relying on them for food, medicine, textiles, utensils, weapons, tools, and construction. English colonists arrived at Jamestown in 1607 and, the next year, were sending back home samples of the pitch and tar extracted from the stately longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) they encountered as they explored the northern reaches of its range. These products proved vital in waterproofing ships’ timbers, and the wood was perfect for house building.

Colonists paid attention to plants, giving them Anglicized names, while also learning the names the Indigenous peoples used:

"[...] American Indians had been observing and using Virginia plants for thousands of years before European settlers arrived, and their contributions to modern plant knowledge came down to us embedded not only in herbal remedies and plant lore but also in plant names of Indian origin like Hickory, Chinquapin, and Pipsissewa. And it was with information gleaned from American Indians that European explorers enriched their first descriptions of Virginia plants" (Hugo and Ware 2012).

The richness of the plant life in the Virginia colony appealed to naturalists, who began painstakingly studying them. They collected and preserved them by pressing and drying, keeping track of where they had been growing, describing habitats and habits in detail. Naming and inventorying these plants helped the Crown evaluate what resources the colony’s flora offered.

The plants of an area make up its flora, and the animals make up its fauna. A published compendium of information on those plants is also called a flora. Virginia had the first “flora” for the so-called New World. Based on the plant collections and descriptions of John Clayton, clerk of Gloucester County, the two-volume Flora Virginica was first published in 1739 and 1742. Carolus Linnaeus, who developed the binomial system of nomenclature, provided publication and naming assistance. Typical of books of science and learning at the time, Flora Virginica was written primarily in Latin, with just a single illustration: a map of what Clayton had explored in the colony, clearly based on Captain John Smith’s well-known map. A second edition, combining the two volumes of the first, was published in 1762. Other than some regional floras and plant lists, Flora Virginica would remain our only flora until the publication of Flora of Virginia (Weakley et al. 2012) in 2012, exactly 250 years later.

What is a Native Plant?

Flora of Virginia defines native plant as a species that was growing in Virginia at the time of European contact. Nonnatives are those that have been introduced, on purpose or inadvertently, since then and have become naturalized here; they manage to reproduce and persist in the wild without the help of humans.

The Virginia Department of Conservation’s Natural Heritage Program defines native plants as:

“[...] those that occur in the region in which they evolved. Plants evolve over geologic time in response to physical and biotic processes characteristic of a region: the climate, soils, timing of rainfall, drought, and frost; and interactions with the other species inhabiting the local community. Thus, native plants possess certain traits that make them uniquely adapted to local conditions, providing a practical and ecologically valuable alternative for landscaping, conservation, and restoration projects, and as livestock forage. In addition, native plants can match the finest cultivated plants in beauty, while often surpassing nonnatives in ruggedness and resistance to drought, insects and disease.” (2022)

The idea that native plants are “natural” is inescapable, yet it is not always easy to determine whether a species is native to a spot. It is incorrect, or at least not too meaningful, to say that a plant is native to the United States, to the East, or even to Virginia, because many species are much more localized, spotty, or even spatially disjunct in their distribution. Some species are native in one county but have been introduced to and thus are nonnative in another county. For others, nativity cannot be verified. Of the 3,348 species or infraspecific taxa covered in the December 2020 major update to the Flora of Virginia App, only about 79% (2,648) are native to Virginia, while 753 are nonnative (and the others not known). Fortunately, county-by-county maps are available showing present knowledge of nativity or nonnativity for each Virginia species that grows in the wild.

As we garden with native plants, we may be conscientious about planting only those species that are deemed native to the county we'll be planting in. For this reason, we need to know whether a plant is, or is not, native to that site. This requires a little research using existing tools.

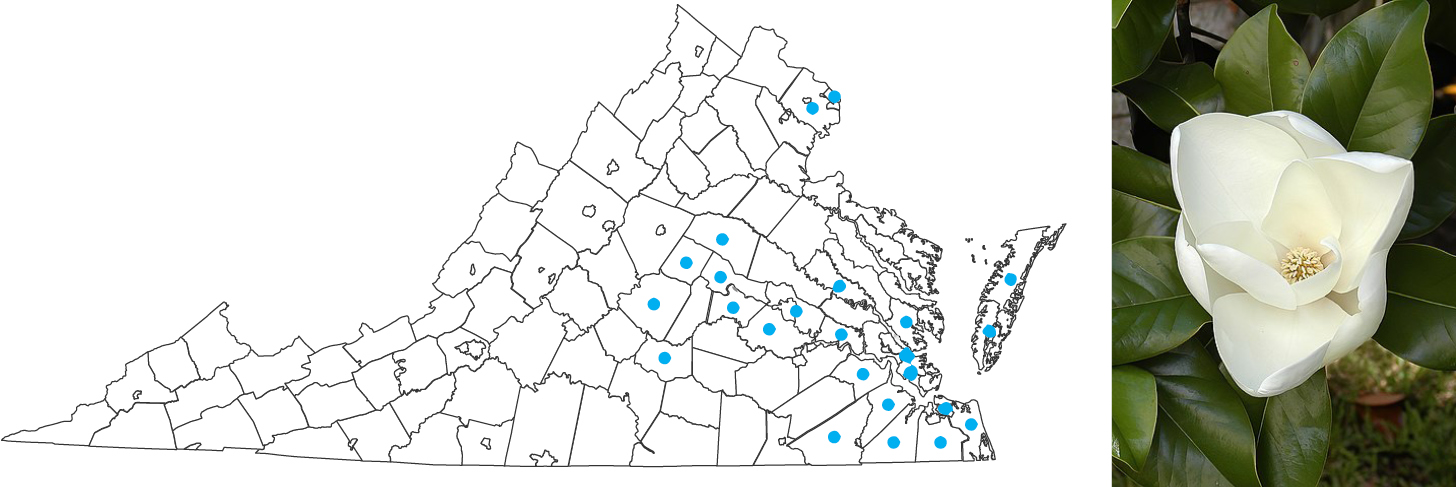

Case Study: Southern Magnolia, Nonnative? How Occurrence and Nativity are Documented

The iconic southern magnolia is not native to Virginia. Magnolia grandiflora is widely seen in the state, and you may feel that the grandeur and perfume of this lovely evergreen tree, celebrated in book, film, and song, is almost intrinsic to life. Though some sources say it’s native in the extreme southeastern corner of Virginia, the Flora of Virginia (Weakley et al. 2012, 2020) and the Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora (Virginia Botanical Associates 2022) do not. In the Flora, if an asterisk precedes a species’ name, it denotes a nonnative. The possibility that the southern magnolia is native to Virginia is tenuous at best, and voucher specimens are known for only a few counties, and those trees had escaped from cultivation.

A voucher specimen is a specimen of a species that depicts clearly its most important physical characteristics and structures. This helps in identifying specimens collected by others and in other regions. It’s a type of study specimen and so has been collected, identified, and preserved by careful drying, and mounted on a standard herbarium sheet of archival paper with a label presenting the details of its collection: collector, date, exact location, and habitat. Once such a specimen has been accessioned by a qualified herbarium (an organized and catalogued collection of such specimens, usually at a university or a museum) it is known as a voucher specimen of the plant.

Some native magnolias

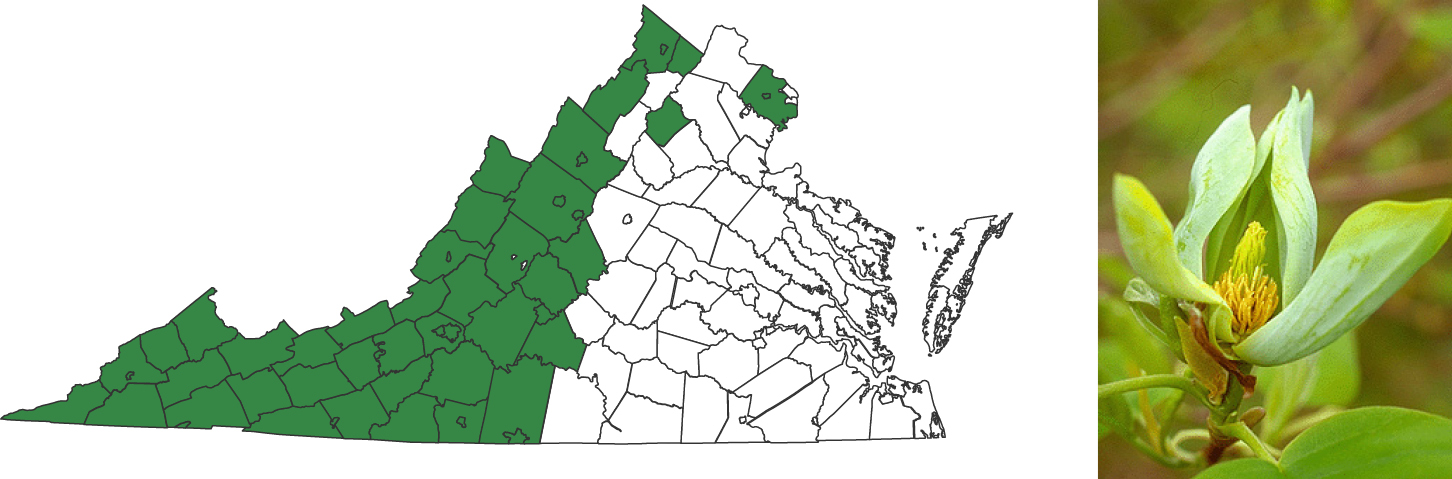

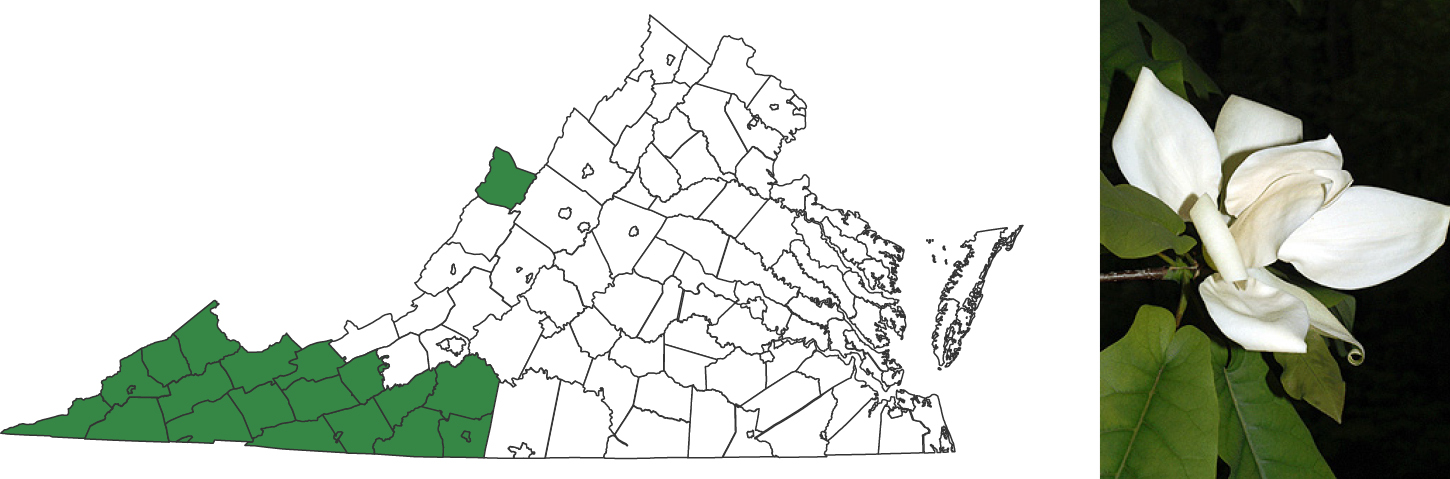

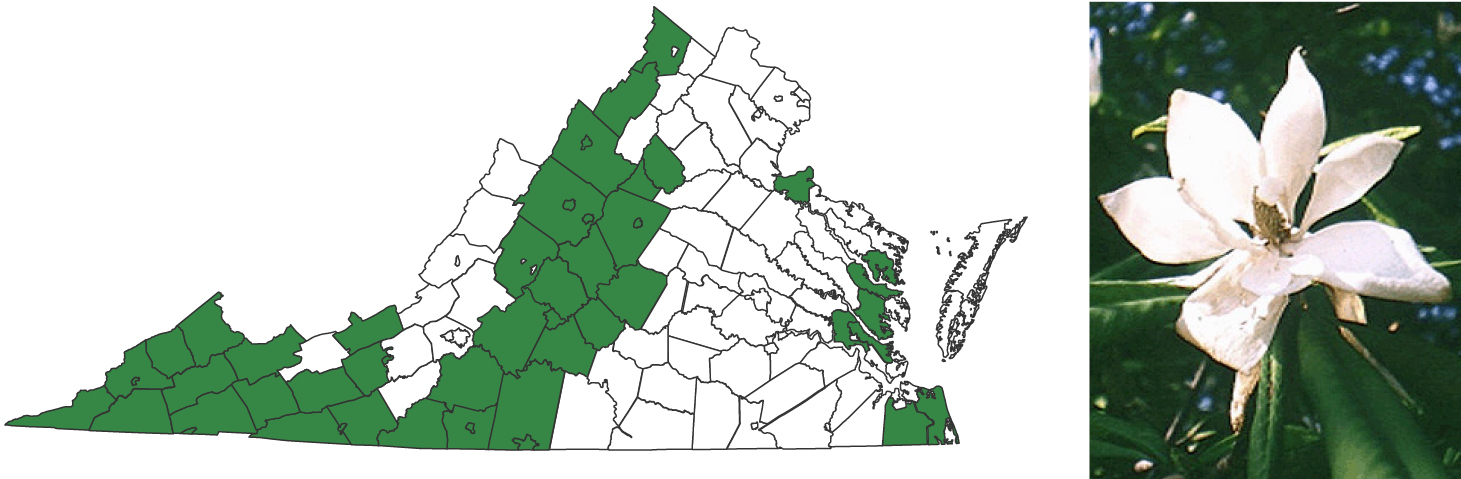

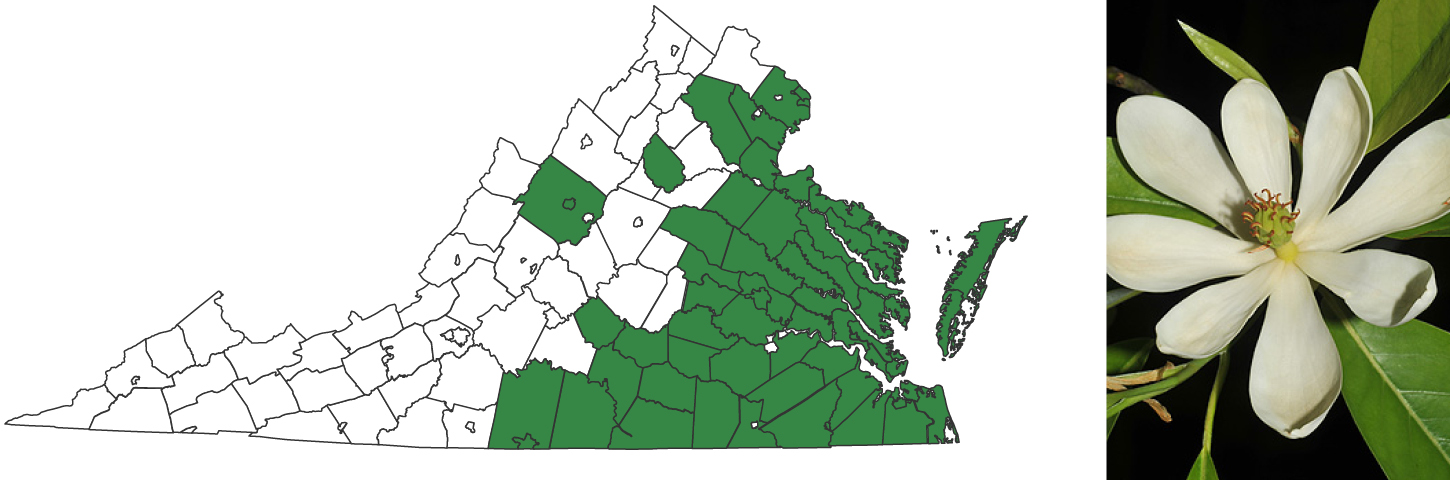

Virginia has some spectacular native magnolias. Here are four, with photographs and range maps adapted from those of the Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora. Green shading means that a voucher specimen exists for the species and that the species is native to that county (in the Digital Atlas, red dots are used for this purpose).

Cucumber-tree, Magnolia acuminata

Fraser magnolia, M. fraseri

Umbrella magnolia, M. tripetala

Sweetbay, M. virginiana

Nativity and Distribution by County: Range Maps

Maps showing county occurrence and nativity of species are provided and updated regularly by the Virginia Botanical Associates, which manages the Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora. Each dot in a county indicates that a voucher specimen exists for the species from that county and, by its color, whether the species is native. Updates take into account new vouchers.

- If there is no dot in a county, the species hasn’t been documented for that county, native or not.

- If a species has a red dot in a county, it is native there; and

- If a species has a blue dot in a county, it is naturalized (defined below) but nonnative.

People have planted southern magnolia possibly in every county in Virginia, but in most counties, they have not yet been found to have escaped cultivation. All the dots in the map for the southern magnolia, above, are blue (indicating introduced status). The voucher specimens did not represent a tree clearly in cultivation or a planted landscape tree but one that had naturalized from a seed dispersed from a cultivated tree by a bird or other animal.

Naturalized describes a nonnative plant that can reproduce and persist in nature without human help. The southern magnolia is naturalized in the blue-dotted counties in its range map. About its habitat, the Digital Atlas says, “Much planted, escaped, and naturalized in upland forests and swamps, especially near urban areas and in southeastern Virginia. Infrequent in the Coastal Plain and outer Piedmont; locally common in the Back Bay region.”

Native Plants Outside of Academia

Observing and studying nature were nothing new, but outside of academics, appreciation of native plants didn’t pick up steam until the 19th century, as new botanical gardens and field guides brought ordinary citizens up close and personal with American native plants. A result was concern, even then, about the damage human activity was doing to the natural world. This led, in part, to the founding of the National Audubon Society in 1905.

Field guides came into their own between the world wars and supplied more information on nomenclature and taxonomy, physical attributes, ecology, and ranges. As the native-plant audience grew, guides became progressively more scientific. Many people can trace their interest in wildflowers and, in particular, native plants, to these guidebooks. They instilled in us the desire to know the plants, to be able to identify them, and to take pride in knowing that natives grow here without anyone’s effort. Yet concern about overcollecting and other damage grew.

Natives: Why Now?

In the United States, interest in preserving wildflowers revved up around 1900. That June, William Trelease, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden, spoke in New York to mark his stepping down as vice president of the botany section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, of which he was past president. He was also the first president of the Botanical Society of America. In closing, he pointedly mentioned the need for “the protection and preservation in every possible way of our native and natural vegetation,” calling it “a matter of prime interest to all botanists, since it will probably affect the very prosecution of many of their studies before the next century shall have been closed.” He added that this was vital as well to “taxonomists, systematists, physiologists, and those studying plant morphology” (Trelease 1900).

Beginning in the 1950s and gaining momentum in the 1960s and 1970s, the environmental movement resulted in laws and policies designed to rein in and clean up pollution and protect (or in the case of most plants, at least designate) threatened and endangered species. Agencies and organizations were formed or grew to study and better care for the environment. Scientists and agencies whose goal it is to conserve and restore native habitats and the organisms that live in them need easy access to information about those habitats and organisms. As the soil, climate, and other physical features provide the habitats for plant growth, the plants provide the habitats for animals and other plants. Plants are also the basis of food webs, creating the building blocks of nutrients from sunlight, carbon dioxide, other atmospheric gases, and chemical components in the soil. Conservation became more and more allied to ecology, the focus not only on individual species but the variety of habitats, and the range of types of ecological communities that both attract and result from the living things in that area.

The Flora of Virginia

Virginia needed a modern volume describing its plant life and providing a tool for people involved in the conservation of plants and environmental protection. The Virginia Academy of Science was created in 1923 and just three years later formed its Committee on Virginia Flora. It kept alive the idea for a new flora but never managed to produce such a work. The massive amount of effort that would make it possible was finally mustered by the Flora of Virginia Project, formed in 2001 with the considerable logistical and scientific support of the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Division of Natural Heritage (the Virginia Natural Heritage Program). With funding from the academy, the Virginia Native Plant Society and its chapters and members, many individuals, foundations, and organizations, including many garden clubs, affiliates of both the Garden Club of Virginia and the Virginia Federation of Garden Clubs, the project became reality. Gronovius and Clayton’s remarkable book was finally supplanted in 2012, exactly 250 years after the publication of its second edition, by the new and massive Flora of Virginia (Weakley et al. 2012).

The print Flora covers 3,164 species and infraspecific taxa (that is, subspecies and botanical varieties, referred to as “species” here for simplicity’s sake) and includes 1,400 illustrations commissioned for the work as aids to identification, as well as keys for identification. Species descriptions include information on habitat, status, phenology (blooming and fruiting times), and botanical and ecological comments to further aid in understanding and identification.

The Flora Project also created an app for smart phones and tablets, making the content of the book accessible to more people, as well as a series of online educational modules.

Be Nice to Natives: Don’t Collect Them or Their Parts

Once you identify a plant that has caught your eye and suits your yard or garden, your task becomes to find it for sale at a nursery, since it's better not to collect from the wild; we don’t want to love our native plants to death. Sustainability is more than a buzzword; it’s the banner under which we expand our appreciation of native plants and their use. Sustainable plants are those capable of continuing to thrive in their native habitat. Many things can undercut sustainability. Apart from the complex threats of human development, the most obvious infractions are collecting native plants or their flowers, seeds, or rootstocks, or, worse, digging the plants out of the wild and transplanting them to your site. This should not be done. Plants are under too many other threats to face affronts from plant lovers. The flowers and seeds are needed in their native habitat, both clearly essential for propagation, continuation of populations, and the establishment, through seed dispersal, of new populations. All parts of the plants support wildlife, from bees, butterflies, and moths and their larvae to bats, birds, and other vertebrates that depend on plants for food, cover, shelter, nesting materials, and habitat. Plants protect other parts of the environment as well, from slowing or preventing erosion to serving as riparian buffers, filtering and retarding storm runoff from terrestrial habitats into aquatic ones.

“It is never acceptable to dig out wild plant material in nature,” says Ashley Moulton, who runs a native-plant operation in Richmond. Moulton formerly coordinated the Chesterfield Extension Master Gardener unit and serves on the boards of the Virginia Native Plant Society and the Flora of Virginia Project. Moulton states “It is illegal to harvest any type of plant material from protected lands, even if they are open to the public.” Unfortunately, laws do not prohibit collecting plants on other property. You must remember that if you were to collect on someone else’s land without permission, you could be held liable for trespassing. Instead of just following the letter of the law, rely on your own ethics: buy from conscientious sellers who collect and propagate native plants using procedures that encourage sustainability.

Be a squeaky wheel: As you window-shop for natives at any nursery, ask questions. Nurseries are increasingly coming on board with native plants. You want to be sure that they are sourcing their native plants and seed with sustainability in mind. Ask managers where they get their native plants or seeds. In a larger nursery, ask them to show you their natives, and if they don’t have any, that’s an opening for a conversation.

Learn in the field: Just because you won’t be collecting, picking, or digging your own natives doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy native plants in the wild. It’s a good idea to do so because in observing living plants, you get a better idea of their habitats and habits, essential for matching plants to desired sites. Not only do you learn the plants and where they live, you begin to hone your instincts as to which plants like what kinds of places and what plants you’d eventually like to find in a nursery.

You are lucky today in that most people have a virtually weightless, high-quality camera in their pocket: a phone. “Take only pictures, leave only footprints” remains a sensible adage to follow as you explore natives in natural places. Pictures give you a nice permanent record of those beautiful plants. Get close-ups of flowers, leaf edges, seed pods, and fruits. It’s also good to back off a bit for a habit shot, illustrating height, posture, and habitat, which you can try to replicate if you buy the plant at a nursery for your garden.

Another popular activity that will take you into the habitats is field trips, including those involving nature journaling. A variety of classes are available, and they usually involve drawing or painting some aspect of a plant or a spot, to which the artist adds notes of observation around the drawing, both narrating the art and complementing it. Some simply sketch or paint, while others only write. The point is to heighten our observational powers about what plants there are, what they look like, how they grow, what animals use them, and where they thrive, all while recalling one’s own yard or project.

Choosing Native Plants to Match Your Site

“To a very considerable extent,” wrote Robert S. Lemmon in 1940, “success in the growing of native plants in a more or less cultivated state hinges on the application of plain common sense, plus the realization that the great majority of the more desirable species have definite likes and dislikes to which we must defer” (Lemmon 1940). Lemmon was writing in Wild Flower on “Plants and Planting Methods for the Native Garden.” A naturalist and writer, in 1938 he founded the horticulture magazine Real Garden and from 1943 to 1951 was editor-in-chief of The Home Garden.

It is common among gardeners to say that “this plant likes partial shade or that one likes wet feet,” but what if we considered a semantic shift that better fits an ecological approach? What if we said that a plant’s “habitat should provide at least partial shade,” or “habitat should not provide soil that is bone dry for extended periods”? The plants are at the mercy of their habitat, and habitat is what you are providing, even if in a “more or less cultivated state.” Make sure plants will get what they need before you buy and plant them. This will make them easier to keep.

As with any plants, you may select a native for many reasons: beauty, desired color, appearance, flowering time, leaf shape etc., but first and foremost, it must be chosen to fit a habitat that is conducive to its thriving. Does it need acid soil or alkaline soil; full sun, part sun, or shade? Is it a beach species that you bought and planted in a spot in the mountains?

Siting and Planting Natives

Lemmon gives good advice: “At the very outset you should make a thorough study of the place you propose to work with,” he wrote. This is nothing new for gardeners, but it’s worth even more serious consideration when you are planting natives. One point is that you want to let the environment and not humans meet the lion’s share of their needs.

Once you have explored your site well, you would do well to test the soil from different areas that appear to be distinct from one another. “The physical and the chemical character of the soil may vary sharply in different sections of even a decidedly small area,” wrote Lemmon. If they are quite different, there could be different microhabitats that could multiply your prospects for diversity.

A soil test will tell you the pH of the soil of interest, as well as levels of nutrients, including phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, zinc, manganese, copper, iron, and boron, as well as the soil’s ability to retain nutrients. You can change some things by adding chemicals, but if it’s natural you’re after, honor that and pick a plant that will like your soil as it is.

Soil sample boxes and information forms are available at Virginia Cooperative Extension offices. Analyses are done at the Virginia Tech Soil Testing Laboratory, and results are provided by email.

Resources for Choosing Native Plants

Once you have assessed your site, it’s time to decide what natives you want, but it may feel more complicated than with mainstream plants. Because natives are slow getting into the retail stream, the labeling of native plants can be variable or include only the plant name. You should not depend on finding detailed siting and planting instructions on labels like you’re used to with big-box-store plants, nor is it always a simple task to find cultivation tips in gardening books. You are fortunate in Virginia that a number of organizations have taken on the task of helping you discover which natives best match your site. Here are some of those sources.

Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora: Virginia Botanical Associates (website)

The habitat and status information, the county-by-county range maps, and most of the photographs you see in the Flora of Virginia app have been provided by the Virginia Botanical Associates, a consortium of Virginia herbarium curators and botanists who document the occurrence of plants and their habitats around the state. It presents and regularly updates this information in its Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora (Virginia Botanical Associates 2022).

Native Plants for Conservation, Restoration, and Landscaping Project

The Native Plants for Conservation, Restoration, and Landscaping Project is a collaboration between the Virginia Natural Heritage program and a number of organizations invested in plant- and nature-related issues. A series of helpful brochures, available as PDFs at that address, was produced listing likely natives for planting in the Coastal Plain, Piedmont, and mountains. You will also find information on planting and restoring grasslands and planting or restoring native vegetation in the riparian zone (riverbanks and stream banks).

Virginia Natural Heritage Program Virginia Native Plant Finder

The Virginia Natural Heritage Program’s online Plant Finder lets you search by scientific or common name and returns data in a grid. You can also use a more detailed search form and provide information about your site, and it returns a matrix of species that fit. Each species links to its page in the Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora, which further describes habitat and status, gives a range map, and provides color photographs.

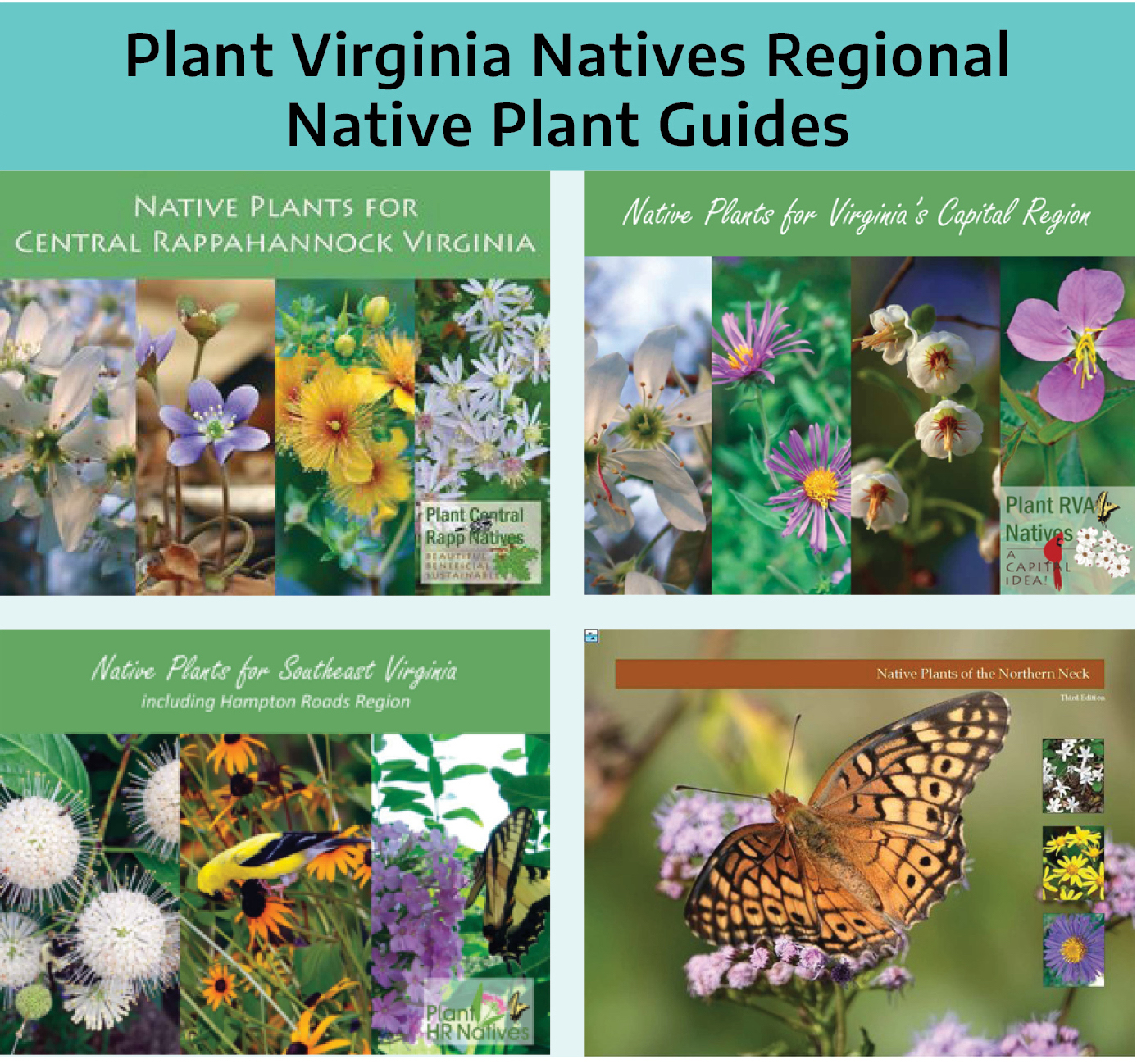

Plant Virginia Natives

Aiming to increase awareness, availability, and use of Virginia’s native plants, the Plant Virginia Natives Initiative was begun in 2011 by the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program, part of a federal–state program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) managed here by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. Goals were to make messaging about natives more consistent and to increase the efficiency of using these resources. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources became a co-chair of the partnership two years later to help fund and expand the program’s reach beyond the coastal zone.

A key focus of the initiative has been to create regional native-plant marketing campaigns and guides. As of 2022, there are now nine such regional campaigns, with more in the planning stages. Seven have published a guide: Northern Virginia, Upper Piedmont, Richmond and environs, the Central Rappahannock region, the Northern Neck, the Eastern Shore, and Southeast Virginia. Southern Piedmont and Southwest Virginia are developing their guides.

Not only do the guides provide great advice on using natives, but they also beautifully illustrate many natives available for the regions, giving specific information that will be invaluable for matching plants with your site. Habitat needs are part of the species description in the Capital Region guide and are presented in a separate matrix in the Upper Piedmont guide. The guide for the Capital Region gives a photograph and description of a species, with its relationships to pollinators and other insects, and it also gives a list of points that will help you determine whether there’s a spot at your site that’s like the plant’s native habitat. The Upper Piedmont guide offers habitat information in a matrix, directing readers to the descriptions and images. The other guides provide information in similar formats.

For more information on the regional campaigns, or to download PDFs of the guides now available, start at the regional project page on the initiative’s site.

The Flora of Virginia: Flora of Virginia Project

What if you like a plant you saw at a native-plant nursery or that you know from a field trip? Before you decide to buy one, you can use the Flora to see how it would fit your site. If you are considering buying a wax myrtle, Morella cerifera, you can find it in the Flora and read its description to see if you have the site for it.

Both the Flora of Virginia book and mobile app are good resources for identifying and learning more about Virginia’s native plants.

Table 19-1: Virginia Native Favorites

Here are some popular Virginia native plants for home gardeners!

| Scientific name | Common name | Family, scientific name | Family, common name | Light | Moisture | Native Range | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sambucus canadensis var. canadensis | Common elderberry | Adoxaceae | Moschatel family | Part shade | Wet | Whole state | Damp to wet soil in fields, clearings, ditches, roadsides, floodplain forests, and swamps; |

| Rhus glabra | Smooth sumac | Anacardiaceae | Cashew family | Full sun, part shade, shade | Dry | Nearly whole state | Old fields, clearings, fencerows, and roadsides; occasionally in natural woodlands. |

| Asimina triloba | Pawpaw | Annonaceae | Custard-apple family | Full sun, part shade, shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Well-drained floodplain forests, mesic to occasionally dry upland forests, wet flatwoods, and swamp hummocks. |

| Asclepias syriaca | Common milkweed | Apocynaceae | Dogbane family | Full sun | Medium | Whole state | Fields, pastures, roadsides, and other open, disturbed habitats. |

| Asclepias tuberosa var. tuberosa | Butterfly-weed | Apocynaceae | Dogbane family | Full sun | Dry to medium | Whole state | Dry woodlands, clearings, fields, pastures, and roadsides. |

| Ilex verticillata | Winterberry | Aquifoliaceae | Holly family | Full sun, part shade | Medium to wet | Nearly whole state | Alluvial swamps, seepage swamps, bogs, ponds, and depression swamps; occasionally in well-drained floodplain forests and mesic upland forests. |

| Arisaema triphyllum ssp. triphyllum | Common jack-in-the-pulpit | Araceae | Arum family | Shade | Medium | Whole state | Mesic upland forests, floodplain forests, and swamp hummocks. |

| Achillea millefolium | Common yarrow | Asteraceae or Compositae | Aster or composite family | Full sun | Dry to medium | Whole state | Ubiquitous in fields, meadows, roadsides, clearings, mesic to dry upland forests, and other habitats. |

| Conoclinium coelestinum | Ageratum | Asteraceae or Compositae | Aster or composite family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Floodplain forests, alluvial swamps, moist to wet meadows, old fields, clearings, and other disturbed, open or shaded sites. |

| Eurybia divaricata | White wood aster | Asteraceae or Compositae | Aster or composite family | Part shade, shade | Dry to medium | Whole state except eastern counties | Mesic to dry upland forests, woodlands, shaded outcrops, well-drained floodplain forests, seepage swamps, and fens. |

| Eutrochium purpureum var. purpureum | Sweet-scented joe-pye-weed | Asteraceae or Compositae | Aster or composite family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Mesic to dry-mesic upland forests; less frequently in dry forests, woodlands, barrens, well-drained floodplain forests, seepage swamps, and fens. |

| Helenium autumnale | Common sneezeweed | Asteraceae or Compositae | Aster or composite family | Full sun, part shade | Dry to medium | Nearly whole state | Bogs, fens, seeps, riverbanks and bars, floodplain forests, freshwater and oligohaline tidal marshes, tidal swamps, wet fields and meadows; also in high-elevation grassy balds. |

| Solidago nemoralis var. nemoralis | Gray goldenrod | Asteraceae or Compositae | Aster or composite family | Full sun, part shade, shade | Dry | Nearly whole state | Open forests, woodlands, barrens, clearings, old fields, and road banks; most characteristic of dry soils, but occasionally occurring in seasonally saturated or alternately wet and dry hardpan soils, especially in the Coastal Plain. |

| Podophyllum peltatum | Mayapple | Berberidaceae | Bayberry family | Part shade, shade | Medium | Whole state | Mesic to dry-mesic upland forests, well-drained floodplain forests, and various moist, disturbed habitats. |

| Campsis radicans | Trumpet-creeper | Bignoniaceae | Bignonia family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Floodplain forests, swamp forests (alluvial, nonriverine, tidal, and maritime), maritime forests, dune woodlands and scrub, various upland forests, rocky and sandy woodlands, old fields, and fencerows. |

| Mertensia virginica | Virginia bluebells | Boraginaceae | Borage family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Central VA and many western counties | Rich soils of well-drained floodplain forests, low-elevation cove forests, and mesic slope forests. |

| Lobelia cardinalis | Cardinal flower | Campanulaceae | Bellflower family | Full sun, part shade | Medium to wet | Whole state | Floodplain forests, alluvial swamps, seepage swamps, maritime swamps, tidal swamps, tidal freshwater and oligohaline marshes, wet meadows, ditches, and low roadsides. |

| Stellaria pubera | Star chickweed | Caryophyllaceae | Pink family | Shade | Medium | Whole state except eastern counties | Mesic to dry forests; most abundant on, but not restricted to, base-rich substrates. |

| Cornus florida | Flowering dogwood | Cornaceae | Dogwood family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Whole state | Common understory tree in a wide variety of mesic to dry upland forests; also in borders, clearings, old fields, and well-drained floodplains. |

| Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana | Eastern redcedar | Cupressaceae | Cypress family | Full sun, part shade, shade | Dry | Whole state | Dry upland forests, rocky woodlands, barrens, old fields, fencerows, and sandy soils of the Coastal Plain. |

| Carex stricta | Tussock sedge | Cyperaceae | Sedge family | Full sun, part shade | Wet | Nearly whole state except southwest mountains and southwest piedmont | In a wide range of wetlands, including bogs, fens, seeps, swamps (all types), wet meadows, beaver ponds, depression ponds, freshwater to oligohaline tidal marshes, and floodplain forests |

| Scirpus cyperinus | Woolgrass | Cyperaceae | Sedge family | Full sun, part shade | Wet | Nearly whole state | Freshwater and oligohaline tidal marshes, tidal swamps, alluvial swamps (particularly in seasonally flooded sloughs), maritime swamps, interdune swales and ponds, depression swamps and ponds, bogs, fens, seeps, impoundments, beaver wetlands, ditches, wet meadows, and other wet disturbed habitats |

| Diospyros virginiana | Common persimmon | Ebenaceae | Ebony family | Full sun, part shade | Dry to medium | Nearly whole state | Weedy tree in old fields, fencerows, and roadsides; also scattered in a range of natural habitats, including swamp forests, depression ponds, dune woodlands and scrub, rocky woodlands, and the understory of mesic to dry upland forests. |

| Kalmia latifolia | Mountain laurel | Ericaceae | Heath family | Part shade | Medium | Whole state | Mesic to dry, acidic forests, woodlands, and shrub balds; often in sandy, rocky, or organic-rich soils; less typically in bogs and seepage wetlands. More or less common throughout, except in the outer and far se. |

| Rhododendron periclymenoides | Wild azalea | Ericaceae | Heath family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Mesic to dry, acidic forests, seepage swamp hummocks, and stream banks. |

| Fagus grandifolia | American beech | Fagaceae | Beech family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Whole state | Mesic to dry-mesic upland forests, very well-drained floodplain terraces, and bluffs; most common on well-drained, acidic, nutrient-poor soils but found in a variety of soils. |

| Hamamelis virginiana | Witch hazel | Hamamelidaceae | Witch hazel family | Part shade | Medium | Whole state | Mesic to dry upland forests, occurring in a wide range of habitats, elevations, and community types. |

| Hydrangea arborescens | Wild hydrangia | Hydrangeaceae | Hydrangea family | Part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Mesic to dry, usually rocky forests, boulder fields, stream banks, cliffs, and outcrops. |

| Hypericum prolificum | Shrubby St. John’s-wort | Hypericaceae | St. John’s-wort family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Dry, open forests, rocky woodlands, barrens, clearings, riverside prairies and outcrops, often on mafic or moderately to strongly calcareous substrates; also in rich floodplain forests, mafic and calcareous fens, and interdune swales. |

| Sisyrinchium angustifolium | Narrow-leaved blue-eyed-grass | Iridaceae | Iris family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Whole state | Mesic to dry upland forests, woodlands, fields, meadows, and floodplain forests. |

| Claytonia virginica | Spring beauty | Montiaceae | Montia family | Part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Well-drained floodplain forests, mesic and dry-mesic upland forests, and old fields; most characteristic of, but not restricted to, base-rich soils. |

| Osmundastrum cinnamomeum var. cinnamomeum | Cinnamon fern | Osmundaceae | Royal farn family | Part shade, shade | Medium to wet | Nearly whole state | Seepage swamps, wet flatwoods, bogs, fens, pocosins, floodplain forests, alluvial and tidal swamps; usually in acidic, often peaty soils but also in base-rich soils of mafic seepage wetlands; occasionally in low-elevation mesic forests and frequently in Northern Red Oak and northern hardwood forests at high elevations. |

| Sanguinaria canadensis | Bloodroot | Papaveraceae | Poppy family | Part shade, shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Mesic to dry-mesic upland forests, dry calcareous forests and woodlands, well-drained floodplain forests; most numerous in moderately to strongly base-rich soils. |

| Chelone glabra | White turtlehead | Plantaginaceae | Plantain family | Part shade | Medium to wet | Nearly whole state | Seeps and seepage swamps, alluvial and tidal swamps, floodplain forests, stream banks, bogs, fens, and wet meadows. |

| Eragrostis spectabilis | Purple lovegrass | Poaceae or Graminae | Grass family | Full sun | Dry to medium | Nearly whole state | Dune grasslands, scrub, and woodlands; interdune swales, river shores and bars, riverside prairies, dry woodlands and barrens, clearings, fields, roadsides, and other open, disturbed habitats. |

| Adiantum pedatum | Northern maidenhair fern | Pteridaceae | Maidenhair fern family | Part shade, shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Base-rich soils of cove forests, mesic and dry-mesic slope forests, well-drained floodplain forests, and calcareous ravines in the Coastal Plain; occasionally on mesic or periodically wet calcareous or mafic boulder fields. |

| Aquilegia canadensis | Wild columbine | Ranunculaceae | Buttercup family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Dry forests, woodlands, barrens, and rock outcrops throughout; shell-marl slopes, bluffs, and shell middens in the Coastal Plain. Although most numerous on subcalcareous, calcareous, and mafic substrates, in the higher mountains it is more tolerant of acidic soils and varied habitats, including mesic to dry-mesic forests, meadows, and roadsides. |

| Thalictrum thalictroides | Rue-anemone | Ranunculaceae | Buttercup family | Part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Mesic to dry upland forests and well-drained floodplain forests; grows in a variety of soils, but somewhat restricted to base-rich soils in the Coastal Plain. |

| Aronia arbutifolia | Red chokeberry | Rosaceae | Rose family | Full sun, part shade | Medium | Nearly whole state | Bogs, fens, seeps, seepage swamps, tidal swamps, acidic alluvial swamps, wet flatwoods, pocosins, and borders of depression ponds; occasionally in mesic or even dry upland forests. |

| Rosa carolina ssp. carolina | Carolina rose | Rosaceae | Rose family | Full sun | Medium to wet | Nearly whole state | Dry-mesic to dry (rarely mesic) upland forests, woodlands, barrens, clearings, old fields, pastures, and roadsides. |

| Rosa palustris | Swamp rose | Rosaceae | Rose family | Full sun | Wet | Nearly whole state | Swamps (all types), tidal freshwater and oligohaline marshes, interdune swales and ponds, bogs, fens, seeps, and old beaver wetlands. |

| Mitchella repens | Partridge-berry | Rubiaceae | Madder family | Part shade, full shade | Medium | Whole state | Ubiquitous in dry to mesic forests, woodlands, and on hummocks of bottomland forests and swamps. |

| Viola pubescens | Yellow violet | Violaceae | Violet family | Part shade | Dry | Nearly whole state | Depends on variety |

Going Native, but to What Degree?

As with any plan for a garden or landscape, it’s seldom all-or-nothing, and a range of possibilities awaits each gardener. Starting at the low end of the scale, even a yard that is populated entirely from the garden department of a major building-supply store almost certainly has at least some natives in it. Unless the ground was shaved to the subsoil during development, which does happen, the transition to native gardening has probably already begun: trees that escaped felling during construction, others planted early upon occupation, the obligatory dogwood or two (Cornus spp.), or a redbud (Cercis canadensis). You may find some phlox a friend passed on, not realizing it was native, or a trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans) whose demise you have often pondered but luckily never got around to.

Other than such native accidentals, you may well find that your lot is more typically nonnative: tight foundation plantings of traditional but nonnative standbys like Asian azaleas, Chinese hollies, nandinas, and barberries. You may see hedges of privet or Bradford pears, and walls of nonnative wisterias, Japanese honeysuckle, or English ivy. All of this surrounding a manicured monocultural expanse of a nonnative grass.

Start Slow and Small

As you think about how you can make your yard or community more suited to its natural habitat using native plants, you need to plan. It’s generally best to start small. Going a little at a time and being selective is a good rule of thumb. Unless you have a big patch of open field to transform into a native wildflower meadow, you may not want to start by trying for total replacement, at least not at the outset. This will also help you to think now about how your planting will affect conditions once things become established.

As you go, consult references to learn which are the more invasive or problematic. What if you have a lot of Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense) and boxwood (Buxus sempervirens), both nonnative, and wonder which would be better replaced with natives if you could only replace one? Use the Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora to help you identify which has been introduced in more counties, therefore likely posing a greater risk of escape. For example, when you search for boxwood on the Digital Atlas range map, you see only six widely spaced counties with dots, all blue, indicating nonnative, though not terribly invasive. Chinese privet is a different story, with a blue dot in nearly every county. With masses of bluish-purple berries attractive to birds, the seeds are often dispersed willy-nilly. Boxwoods pose a lesser risk of escape, and it would therefore be better to remove Chinese privet.

You can also look up nonnative species to see if they appear in DCR’s invasive plant list. Invasive species identified by DCR are given a rank indicating how much of a threat they pose to the ecosystem. Chinese privet has an invasiveness rank of "high” (yet it is still used in the horticulture industry). The choice is clear: the privet goes.

What if you have azaleas all around your house and are interested in finding native replacements. Removing a few is a more cost-effective option, though some people may choose to uproot them all at once. Even replacing a few can contribute to improving the biodiversity of your landscape.

Virginia has a lot to offer in the native-azalea department, and azaleas are in a familiar genus: Rhododendron. As always, though, check the range map to see whether a species is native to your county. Some species have a restricted range or are mapped only in a few counties.

The following are some native replacements for Asiatic azaleas:

- Rhododendron arborescens, smooth azalea, sweet azalea

- Rhododendron atlanticum, dwarf azalea

- Rhododendron calendulaceum, flame azalea

- Rhododendron catawbiense, Catawba rhododendron

- Rhododendron cumberlandense, Cumberland azalea

- Rhododendron maximum, great rhododendron, great laurel

- Rhododendron periclymenoides, pinxterflower

- Rhododendron prinophyllum, early azalea

- Rhododendron viscosum var. viscosum, southeastern swamp azalea

Don’t forget the rhododendrons’ cousin, the mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia, native to every Virginia county.

Warning Internet Searchers

Always be cautious about where you get information online. Not all websites will have correct information on Virginia native. Look for .edu or .gov sources, or use the resources described above. For example, if you were looking for native plants for hedges, Plant NOVA Natives’ page on hedges is a reliable option, suggesting:

- Carpinus caroliniana, American hornbeam

- Cornus amomum, silky dogwood

- Itea virginica, Virginia sweetspire

- Morella cerifera, wax myrtle

- Rhus aromatica, fragrant sumac

- Rosa carolina, Carolina rose

- Rosa virginiana, Virginia rose

Why Are Native Plants Important?

As gardeners, we can learn how to transform gardens by using more native plants and, in the process, reconnect natural habitats fragmented by human activity. Planting natives can help invite wild animals to breed, nest, develop, and dine in your native-plant-fortified environments.

With increases in human development and expansion of built areas, native habitats have been fragmented into "islands." These islands can be so small as not to provide enough space for some animals’ territory, which ensures a breeding pair plenty of room for raising young and foraging. With these islands, species can be so far apart that mating becomes more difficult, opportunities for mating are more scarce, and genetic diversity of the species in that location diminishes.

“The negative impact on habitat connectivity due to anthropogenic activities can cause isolation of populations, with consequences on intercrossing between individuals and effective gene flow,” wrote Zubaria Waqar and her colleagues, researchers from the Brazilian state of Bahia (Waqar et al. 2021). “According to genetic variation dynamics, over space and time a few genotypes of a population can become dominant over others due to natural selection, genetic drift, and inbreeding.”

“When we design our home landscapes, too many of us choose beautiful plants from all over the world, without considering their ability to support life within our local ecosystems,” professor and author Doug Tallamy wrote in “The Chickadee’s Guide to Gardening” (Tallamy 2015). He tells how he counted the caterpillars on two trees in his neighbor’s yard: a Bradford pear (Pyrus calleryana ‘Bradford’), from Asia, and a young native white oak (Quercus alba) of about the same size. On the native oak, he found 419 caterpillars, representing 19 species. On the Bradford pear, he found one inchworm. The next day he found 233 on the oak, of 15 species, and one caterpillar on the nonnative Bradford pear.

He describes the often toxic, or at least unpalatable, chemical defenses plants have developed over millennia. Some species “have evolved to eat oak trees without dying, while others have specialized in native cherries or ashes and so on,” Tallamy writes. “But local insects have only just met Bradford pears, in an evolutionary sense, and have not had the time … required to adapt to [the trees’] chemical defenses. And so, Bradford pears stand virtually untouched in my neighbor’s yard.”

In Tallamy’s example of the chickadee, both parents feed their nestlings caterpillars, bringing one to the nest every three minutes. Tallamy calculates that for 14 hours of feeding time a day, for 16 to 18 days before the nestlings fledge, that’s 350 to 570 caterpillars a day, depending on the brood size. “So, an incredible 6,000 to 9,000 caterpillars are required to make one clutch of chickadees.” Larger bird species are likely to require even more insects to feed their young.

Some might wonder why the birds can’t just feed in wild areas. “That worked in the past, but now there simply is not enough ‘nature’ left,” Tallamy says. “And it shows.” You’ve read about the plight of the monarch butterfly. Birds are hurting too. Rosenberg et al. (2019) reported in Science that, since 1970, nearly 3 billion U.S. birds have been lost. That’s 29 percent of 1970 levels. “Species extinctions have defined the global biodiversity crisis,” they wrote, “but extinction begins with loss in abundance of individuals that can result in compositional and functional changes of ecosystems.” The monarch and the birds are proverbial canaries, and they portend worse. “These bird losses are a strong signal that our human-altered landscapes are losing their ability to support bird life,” Rosenberg told Gustave Axelson, who heralded the researchers’ findings in a blog entry on All About Birds, the site of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (Axelson 2019). “These results have major implications for ecosystem integrity, the conservation of wildlife more broadly, and policies associated with the protection of birds and native ecosystems on which they depend,” Rosenberg and his colleagues wrote (2019).

In recent years, more people are understanding that by planting natives in their landscapes, they can help the environment. They are realizing that their yards present an opportunity for species conservation and are inviting nature in to share their spaces.

Truly Native: Avoid Cultivars and Hybrids

When looking through what’s on offer at native nurseries or in native catalogs, you will at some point get down to the nitty-gritty of the why of native plants. You may encounter plants marketed as native that have a cultivar name in single quotes on the label or that are hybrids between two plants, one of them possibly a nonnative. Gene combinations resulting from artificial selection or hybridization for certain “more desirable” traits are not considered native.

When looking for plants that have evolved in your county, that are truly native there, you may want to provide native animals the “wild type” of plants, the native genotype with which they have coevolved. A cultivar or a hybrid falls short, as do nativars, or cultivars of native species, a term that piques the interest of native-plant people but indicates something otherwise. If you can’t find the truly native species at a nursery, wait a while until you do find it.

Here’s part of the Virginia Native Plant Society’s statement on cultivars:

"VNPS recognizes that wild-type plants may be difficult to find in the marketplace, and that cultivars and hybrids of native plant species can offer distinctive characteristics which increase their effectiveness in landscape design. However, due to documented cases where the introduction of cultivated plants has negatively impacted natural populations, and because the ecological implications of such plants have not yet been adequately evaluated, we recommend avoiding hybrids and using cultivars only in locations distant from natural areas (e.g., urban gardens) and to exercise caution in the selection of plants that vary significantly from the wild type (e.g., in flower structure, flower color, fruit size and leaf color)."

Case Study: What Native Plants Mean to the Monarch Butterfly

The plight of the monarch butterfly has upped the focus on native plants, the relationship between natives and animals, and the domino effect of environmental crises. It has people planting butterfly weed and other milkweeds (a group of required host plants for monarch larvae and thus for egg-laying by adult females) like never before. In the United States, there are two separate populations of monarch butterflies: the population east of the Rockies (some 99 percent of the North America population), which spends the summer along the eastern U.S. and eastern Canadian border and winters in central Mexico, and the western population, which lives along the Pacific coast and spends the winter in California.

The eastern population faces ecological peril in its summer home in the United States and Canada, in its winter home in Mexico, and in between. As of 2022, the monarch is not listed under the Endangered Species Act, but the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service has determined that listing is warranted, so it may be considered for inclusion soon. Although there is not scientific consensus on the reason for the monarch’s population decline, threats include habitat loss and degradation, pesticides, illegal logging, climate change, and the lack of milkweeds.

The eastern monarchs migrate north from Mexico to breed. After three to five short-lived generations have been produced, the season’s last generation heads to Mexico to winter, roosting in clusters in the oyamel fir (Abies religiosa) forest of the Sierra Madre at 8,000 to 12,000 feet. The monarch differs from other butterflies, which don’t migrate such great distances or may overwinter as larvae or pupae. Monarchs could not survive northern winters. (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2022).

Working for monarchs in the backyard

The U.S. Department of Forestry, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and other federal and state agencies are involved in work to restore monarch habitat. Read more about conservation efforts here. Gardeners can also help make their landscape and their community more favorable for monarchs.

Susan Walton, of the Peninsula Master Naturalist chapter, teamed up with Virginia Department of Transportation Superintendent Kevin Sears to identify and protect patches of milkweed growing on the shoulders of U.S. 17 in Gloucester County. Walton and Sears showed that the answer to this need was as simple as a change in mowing patterns around the milkweed habitat, an action that could be easily replicated in any milkweed- containing shoulder being mowed. Even a milkweed patch that was accidentally cut in early summer would grow again, ready for the last monarch generation of the season.

In 2013, Master Naturalists from the Historic Rivers Chapter, including York and James City counties and Williamsburg, worked to involve students at 10 elementary schools and one high school to build a monarch waystation (milkweed-containing monarch habitats) at each. Word spread, and outdoor classrooms and pollinator habitats were created at 23 schools. The following year, a total of 650 monarchs were tagged to monitor migration (Virginia Master Naturalist Program 2015).

Virginia Invasives: 8 More Reasons to Plant Native Plants

Nonnative plants can become invasive or harbor pathogens that will affect native species. Here are a few examples of invasive plants that have disrupted our ecosystems.

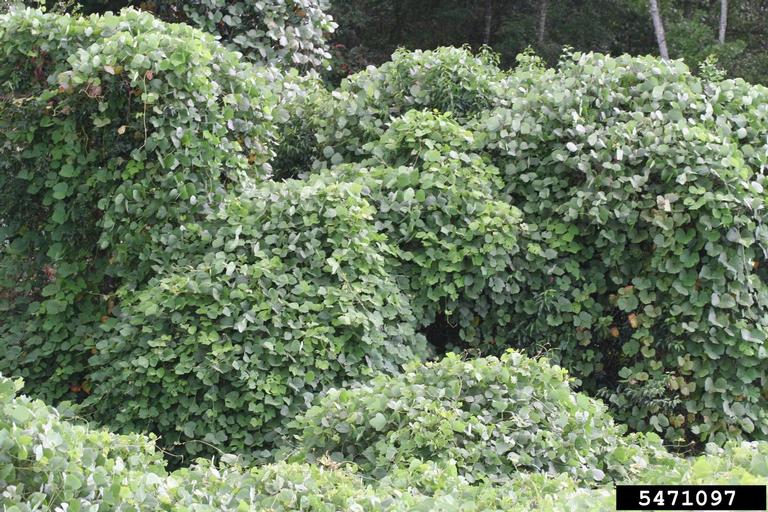

Kudzu, Pueraria montana: Kudzu was once the infamous star of invasive plants in many parts of Virginia. Sadly, it has a lot more company nowadays. A legume native to Asia, kudzu was first brought in as an ornamental and later found use in retarding erosion. It had other ideas and spread rampantly, often engulfing anything in its path. The Nature Conservancy has called it “the invasive vine that ate the South.”

Japanese honeysuckle, Lonicera japonica: Nearly everyone in Virginia knows this plant. It’s beautiful and sweet smelling, and its nectar is delicious, but don’t be fooled. This nonnative has found its way into every county in the state. If you have it in your yard or garden, you have a problem, and it doesn’t respect boundaries. The Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora says, “Nearly ubiquitous in wet to dry forests, old fields, disturbed floodplains, and various open habitats; shade-tolerant and very invasive in many natural community types.” It’s a back-breaker to get rid of, but it must be done. Try coral honeysuckle, Lonicera sempervirens, a favorite of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird.

Tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima: Betty Smith might have put this species front and center in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, but this made-to-invade plant is now ubiquitous and destructive in Virginia and beyond. Arriving in the United States via its strawlike seeds, which were used as packing materials to protect fragile porcelain, ailanthus creates those seeds in huge numbers. Making matters worse, the tree sprouts strongly from the roots when is cut down. In addition, it’s a preferred host plant for the equally invasive spotted lanternfly. A new threat to Virginia, the planthopper first appeared in the northwestern part of the state in 2018 and has since spread.

Chinese wisteria, Wisteria sinensis: It is such a shame that many invasives would be beautiful if they weren’t so dastardly. Planted for its beauty and fragrance, it broke free to become established in woods, borders, and fencerows, says the Digital Atlas. It’s common locally in the eastern half of Virginia. Bite the bullet and pull it out. The similar Wisteria frutescens var. frutescens, Atlantic wisteria, is native to parts of the Coastal Plain, though it's rare.

Japanese stiltgrass, Microstegium vimineum: Another example of something that could be loved it if weren’t so damaging, this aggressive destroyer creates a carpet that chokes out everything in its path. Another plant that stowed away as packing material in shipments of porcelain, it is also now common in nearly every Virginia county. Control requires early and close mowing before flowering and seed formation. It’s an annual, and its seeds survive in the soil for years, unaffected by herbicides applied directly to the blades of grass.

Hydrilla, Hydrilla verticillata: You may be familiar with many of these invasive nonnatives, but hydrilla’s an aquatic and possibly not so well known. The Flora of Virginia calls it “[o]ne of our most invasive aquatic weeds, often clogging waterways and boat motors and outcompeting native aquatics.” From Africa, it first got a foothold in Florida, probably via the aquarium trade (Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation and Virginia Native Plant Society 1997).

Autumn olive, Elaeagnus umbellata: Another plant that’s visually pleasing but on the most-wanted list of nonnative invaders. From Asia, this shrub was imported for wildlife, with whom the fruits are indeed popular, which explains its invasiveness in waste ground and in natural habitats.

Stowaway diseases and pests: Nonnatives can carry diseases or pests for which native plants have not evolved coping mechanisms. Some are well known: Dutch elm disease, the emerald ash borer, the hemlock woolly adelgid, and the infamous chestnut blight. Hitting Virginia’s state tree, the flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), is the fungal disease dogwood anthracnose. Since the 1970s, native dogwoods have been plagued by anthracnose, caused by the fungus Discula destructiva (Miller et al. 2016). The disease was first noticed on native dogwoods near U.S. ports, where it is believed to have entered on dogwood plants from Asia. There, the fungus doesn’t cause severe disease in native dogwoods (Miller et al. 2016). By the early 1990s, it had caused major losses and damage in the flowering dogwood, especially in the South (Anderson et al.).

Additional Resources

Online resources

- Virginia Master Naturalist Program: Extension Master Gardeners are already collaborating with Master Naturalists, and there is much more to collaborate on, including native plant–pollinator demonstration gardens, Plant Virginia Natives campaigns, habitat restoration projects involving native plant communities, and educational programs about native plants.

- Virginia Native Plant Society

- Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Natural Heritage Program: Information on native plants, invasive species, and Virginia conservation and ecology.

- Blandy Experimental Farm at the State Arboretum of Virginia

- Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora

- Flora of Virginia Project.

- Plant Virginia Natives Initiative.

- USDA’s PLANTS Database

- Virginia Extension Master Gardener Tree Steward Manual

- “Wildflower ethics and native plants” Article from the USDA Forest Service

- North Carolina State University Extension Plant Toolbox

- Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder

- Heffernan, K., E. Engle, and C. Richardson. 2014. Virginia Invasive Plant Species List. Natural Heritage Technical Document 14-11. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage, Richmond. https://www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural-heritage/document/nh-invasive-plant-list-2014.pdf. Available March 2022.

- Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. 2020. Habitat at Home, 2020 revision. Text and photography by Carol A. Heiser. https://dwr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/media/Habitat-at-Home.pdf. Available April 2022.

- "Biodiversity for the Birds: Non-native plants in homeowners’ yards endanger wildlife, UD researchers report," LaPenta, Dante. 2022.

Books

- Botanical Artists for Education & the Environment. 2014. American Botanical Paintings: Native Plants of the Mid Atlantic, a Book for Artists and Gardeners. B.S. Driggers, editor. Lydia Inglett Ltd. Publishing, Hilton Head, South Carolina.

- Capon, B. 2010. Botany for Gardeners. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Darke, R., and D. Tallamy. 2014. The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Finch, B., B.M. Young, R. Johnson, and J.C. Hall. 2012. Longleaf, Far as the Eye Can See: A New Vision of North America’s Richest Forest. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

- Hamilton, H., and G. Hall. 2013. Wildflowers & Grasses of Virginia’s Coastal Plain. Sponsored by the John Clayton Chapter of the Virginia Native Plant Society. BRIT [Botanical Research Institute of Texas] Press, Fort Worth.

- Harris, J.G., and M.W. Harris. 2001. Plant Identification Terminology: An Illustrated Glossary, 2nd ed. Spring Lake Publishing, Spring Lake, Utah.

- Holm, Heather. Pollinators of Native Plants: Attract, Observe and Identify Pollinators and Beneficial Insects with Native Plants. Minnetonka, MN: Pollination Press LLC, 2014.

- Norris, Kelly. New Naturalism: Designing and Planting a Resilient, Ecologically Vibrant Home Garden. Beverly, MA: Cool Springs Press, 2021.

- Rainer, T., and C. West. 2015. Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Slattery, B.E., K. Reshetiloff, and S.M. Zwicker. 2003, 2005. Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping: Chesapeake Bay Watershed. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office, Annapolis, Maryland. https://dnr.maryland.gov/criticalarea/Documents/chesapeakenatives.pdf. Available April 2022.

- Tallamy, D.W. 2007. Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Tallamy, D.W. 2020. Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation that Starts in Your Yard. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Tallamy, D.W. 2021. The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Virginia Department of Forestry. n.d. Rain Gardens Technical Guide: A Landscape Tool to Improve Water Quality. Virginia Department of Forestry, Charlottesville. https://dof.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/Rain-Gardens-Technical-Guide_pub.pdf. Available April 2022.

- Weakley, A.S., J.C. Ludwig, and J.F. Townsend. 2012. Flora of Virginia. Bland Crowder, ed. Foundation of the Flora of Virginia Project Inc., Richmond. BRIT [Botanical Research Institute of Texas] Press, Fort Worth.

- Weakley, A.S., J.C. Ludwig, J.F. Townsend, and G.P. Fleming. 2020. Flora of Virginia [mobile app]. Bland Crowder, ed. Foundation of the Flora of Virginia Project Inc., Richmond, and High Country Apps, Bozeman, Montana.

References

- Anderson, R.L., J.L. Knighten, M. Windham, K. Langdon, F. Hedrix, and R. Roncadori. [1994.] Dogwood anthracnose and its spread in the South. USDA Forest Service, Atlanta. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5447373.pdf. Available March 2022.

- Axelson, G. 2019. Vanishing: more than 1 in 4 birds has disappeared in the last 50 years. All About Birds. Cornell University, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/bring-birds-back/. Available March 2022.

- Beverley, R. 1705. History and present state of Virginia. R. Parker, London.

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2021. Adelges tsugae (hemlock woolly adelgid) - fact sheet. https://inspection.canada.ca/plant-health/invasive-species/insects/hemlock-woolly-adelgid/fact-sheet/eng/1325616708296/1325618964954. Available March 2022.

- Center for Biological Diversity. 2022. Monarch butterfly. Center for Biological Diversity, Tucson, Arizona. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/invertebrates/monarch_butterfly/

- D’Arcy, C.J. 2000. Dutch elm disease, revised 2005. Plant Disease Lessons, American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, Minnesota. https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/disandpath/fungalasco/pdlessons/Pages/DutchElm.aspx. Available March 2022.

- Darke, R., and D. Tallamy. 2014. The living landscape: designing for beauty and biodiversity in the home garden. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Goatley, M., Jr. 2008. What grass should I grow for my lawn? Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia, and Virginia State University, Petersburg. Crop and Soil Environmental News, March 2008. https://www.sites.ext.vt.edu/newsletter-archive/cses/2008-03/WhatGrass.html (available 3 March 2022). Available March 2022.

- Frost, C.C. 1993. Four centuries of changing landscape patterns in the longleaf pine ecosystem. Pp. 17–43 in S.M. Hermann (ed.), The longleaf pine ecosystem: ecology, restoration and management. Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference, No. 18. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, Florida.

- Hance, J. 2020. Brazil’s Atlantic Forest (Mata Atlântica). Mongabay [blog]. https://rainforests.mongabay.com/mata-atlantica/. Available March 2022.

- Hartke, B.B. 2017. Finding fulfillment as a Wildlife Way Station volunteer. Blog. Virginia Native Plant Society, Boyce, Va. https://vnps.org/finding-fulfillment-as-a-wildlife-way-station-volunteer/. Available March 2022.

- Heffernan, K., E. Engle, and C. Richardson. 2014. Virginia invasive plant species list. Natural Heritage Technical Document 14-11. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage, Richmond. https://www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural-heritage/document/nh-invasive-plant-list-2014.pdf. Available March 2022.

- Hill, E.C. 1943. Conserving the native beauty of Virginia. Wild Flower 20(1): 1–3.

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. 2009. Ask Mr. Smarty Plants. [Mr. Smarty Plants replies to a reader’s question about replacing azaleas with native plants.] https://www.wildflower.org/expert/show.php?id=3435&frontpage=true. Available 7 March 2022.

- Lemmon, R.S. 1940. Plants and planting methods for the native garden. Wild Flower 14(1):89–94.

- Michaux, F.A. 1810. The North American sylva, or a description of the forest trees of the United States, Canada and Nova Scotia. F.A. Michaux, 1810. Real-time PCR detection of dogwood anthracnose fungus in historical herbarium specimens from Asia. Plos One 11(4): e0154030. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154030. Available March 2022.

- Miller, S., H. Masuya, J. Zhang, E. Walsh, and N. Zhang. 2016. Real-time PCR detection of dogwood anthracnose fungus in historical herbarium specimens from Asia. PloS ONE 11(4): e0154030. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154030.

- National Audubon Society. 2022. History of Audubon and science-based bird conservation. https://www.audubon.org/about/history-audubon-and-waterbird-conservation. Available March 2022.

- Newcomb, L. 1989. Newcomb’s wildflower guide. Reprint edition. Little, Brown and Company, Boston.

- Palmer, M.J. 2018. Defenders of Mexico’s environment chronicle their battles: poet Homero Aridjis and Betty Ferber have spent a lifetime fighting to save endangered species and ecosystems in Latin America. Earth Island Journal, August 8, 2018. Earth Island Institute, Berkeley, California. https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/articles/entry/defenders-of-mexicos-environment-chronicle-their-battles/. Available March 2022.

- Ray, J. 1999. Ecology of a cracker childhood. Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis.

- Ricker, P.L. 1937. A history of the wild flower preservation movement. Wild Flower 14(2): 28–30 and 14(2): 49–53.

- Rosenberg, K.V., A.M. Dokter, P.J. Blancher, J.R. Sauer, A.C. Smith, P.A. Smith, J.C. Stanton A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr, P.P. Marra. 2019. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366(6461): 120–124.

- Rothenberg, J. 2014. In defense of the monarch butterfly: a letter to three nations from poets, writers, scientists, & artists. Poems and poetics [blog]. Jacket 2, Philadelphia. https://jacket2.org/commentary/defense-monarch-butterfly-letter-three-nations-poets-writers-scientists-artists. Available March 2022.

- Solyst, J. 2020. The greatest wildlife comeback you’ve never seen: saved from near extinction, wild turkeys are now guarded by vigilant wildlife managers. Chesapeake Bay Program, Recent News. https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/the_greatest_wildlife_comeback_youve_never_seen. Available March 2022.

- Tallamy, D. 2011. A call for backyard biodiversity. Originally published in American Forests magazine, autumn 2009. https://www.americanforests.org/magazine/article/a-call-for-backyard-biodiversity/. Available March 2022.

- Tallamy, D.W. 2007. Bringing nature home: how you can sustain wildlife with native plants. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Tallamy, D.W. 2015. The chickadee’s guide to gardening. New York Times, March 11, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/11/opinion/in-your-garden-choose-plants-that-help-the-environment.html. Available March 2022.

- Tallamy, D.W. 2020. Nature’s best hope: a new approach to conservation that starts in your yard. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Tallamy, D.W. 2021. The nature of oaks: the rich ecology of our most essential native trees. Timber Press Inc., Portland, Oregon.

- Trelease, W. 1900. Some twentieth century problems. Science (New Series) 12(289): 48–62.

- UNESCO. 2008. Twenty-seven new sites inscribed. World Heritage Convention, News, July 8, 2008. UNESCO, Paris. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/453/, available March 2022.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2022. Monarch butterfly frequently asked questions (FAQs). U.S. Forest Service, Washington. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/Monarch_Butterfly/faqs.shtml. Available March 2022.

- Virginia Botanical Associates. 2022. Digital atlas of the Virginia flora [website]. Virginia Botanical Associates, Blacksburg. http://www.vaplantatlas.org/. Available March 2022.

- Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation and Virginia Native Plant Society. 1997. Hydrilla. Invasive alien plant species in Virginia [factsheet series]. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation and Virginia Native Plant Society. https://www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural-heritage/document/fshyve.pdf.

- Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. 2022. Eastern hemlock–hardwood forests. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage, Richmond. https://www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural-heritage/natural-communities/nctb5. Available March 2022.

- Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. 2022. What are native plants? In Native plants for conservation, restoration, and landscaping. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage, Richmond. https://www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural-heritage/nativeplants. Available March 2022.

- Virginia Department of Forestry. 2022. Emerald ash borer. Virginia Department of Forestry, Forest Health Program. Charlottesville. https://dof.virginia.gov/forest-management-health/forest-health/insects-and-diseases/emerald-ash-borer/. Available March 2022.

- Virginia Department of Forestry. 2022. Emerald ash borer in Virginia: an introduction. Story map. Virginia Department of Forestry, Forest Health Program. Charlottesville. https://vdof.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=e2660c30d9cd46cc988cc72415101590. Available March 2022.

- Virginia Master Naturalist Program. 2015. Giving monarchs a boost in Virginia. Virginia Master Naturalist Program, Charlottesville. http://www.virginiamasternaturalist.org/home/giving-monarchs-a-boost-in-virginia. Available March 2022.

- Virginia Tech. 2022. Virginia Tech Soil Testing Lab. Virginia Tech, Blacksburg. https://www.soiltest.vt.edu. Available March 2022.

- Waqar, Z., R.C.S. Moraes, M. Benchimol, J.C. Morante-Filho, E. Mariano-Neto, and F.A. Amato . 2021. Gene flow and genetic structure reveal reduced diversity between generations of a tropical tree, Manilkara multifida Penn., in Atlantic Forest fragments. Genes 2021, 12, 2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12122025.

- Weakley, A.S., J.C. Ludwig, and J.F. Townsend. 2012. Flora of Virginia. Bland Crowder, editor. Foundation of the Flora of Virginia Project Inc., Richmond. BRIT [Botanical Research Institute of Texas] Press, Fort Worth.

- Weakley, A.S., J.C. Ludwig, J.F. Townsend, and G.P. Fleming. 2020. Hydrilla verticillata [species treatment]. Bland Crowder, editor. Flora of Virginia [mobile app]. Foundation of the Flora of Virginia Project Inc., Richmond, and High Country Apps, Bozeman, Montana.

- Worrall, J.J. 2022. Chestnut blight. In Forest pathology: diseases of forest and shade trees. [website.] https://forestpathology.org/canker/chestnut-blight/. Available March 2022.

Attributions

Written by Bland Crowder, Executive Director Flora of Virginia Project

- Marion Lobstein, Associate Professor of Biology, NVCC-Manassas, Adjunct Professor, Blandy Experimental Farm (2022 peer reviewer)