Chapter 18: Habitat Gardening for Wildlife

Chapter Contents:

Landscaping for wildlife is both an art and a science. Whether we use plants creatively as a form of artistic expression or we design the landscape as merely a utilitarian space, we can sustain the biodiversity around us by planning our gardens with an ecological function in mind. When we plan our surroundings in a way that supports complex interactions between plants and animals, we become more fully connected to nature ourselves.

Habitat gardening is an enjoyable way to more fully appreciate nature while improving the available food, water, and cover for birds, amphibians, mammals, and other wild creatures in our landscape. Applying the principles of good vegetative structure and horizontal layering as we add plants to the landscape will provide wildlife with beneficial food sources as well as much needed cover from predators, winter winds, and summer sun. Nest boxes, water features, brush piles and other amenities will enhance the habitat’s value and can be planned as attractive focal points in the garden.

However, as one assesses the existing habitat and makes choices about what plants and amenities to add, care must be taken in the placement of those enhancements, in order to minimize the possibility of attracting “unwelcome” wildlife species. There are no “nuisance wildlife” species; rather, we create the conditions in our landscape that attract wildlife, and sometimes our unwitting choices set the stage for certain wildlife species to become a problem. Therefore, we must plan the habitat garden in a way that balances our need for aesthetics and beauty with the reality of how wildlife will likely use the space as we’ve designed it.

Habitat Loss and Declining Wildlife Populations

The decline of wildlife species is occurring at an alarming, accelerated rate. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) maintains a Wildlife Action Plan (published 2015) which identifies 925 species of greatest concern, classified into four groups or ‘tiers’ that describe varying degrees of population declines attributed to habitat loss. Of these, 290 species or 31% are insects, which are an essential part of aquatic and terrestrial food webs.

Table 18-1: Wildlife groups and numbers

| Wildlife Groups in Virginia (Total Species in Parentheses) | Number of Species of Greatest Conservation Need |

|---|---|

| Mammals (96) | 24 |

| Birds (390) | 96 |

| Fishes (210) | 97 |

| Reptiles (62) | 28 |

| Amphibians (82) | 32 |

| Mussels | 61 |

| Aquatic Crustaceans | 61 |

| Aquatic Insects | 148 |

| Terrestrial Insects | 142 |

| Other Aquatic Invertabrates | 34 |

| Other Terrestrial Invertabrates | 202 |

| Total species of greatest concern | 925 |

Except regularly nesting sea turtle species, list does not include marine wildlife.

Habitat loss is caused by many factors. The most obvious is development and fragmentation of forest, meadow and wetland habitats, as we continue to grow the economy by building commercial and residential sites. This development brings with it a host of factors that adversely impact the remaining or surrounding habitats, and these factors include but are not limited to a prevalence of impervious surfaces that contribute to increased erosion and runoff, which carries chemicals and sediments with it, and the extensive use of lawn and other non-native plants in the landscape for ornamentation. There are adverse impacts occurring in the more rural or agricultural areas, including the routine use of herbicides and pesticides and farming practices that remove hedgerows and large expanses of vegetation in order to maximize production. In addition, as more land disturbance occurs across all these areas—urban, suburban and rural—we’ve seen a connected proliferation of invasive exotic plant species that compete with native plant communities.

The additive effect of all these factors or pressures on the environment is an overall reduction in the quantity and quality of aquatic and terrestrial habitats, which is the single most important reason that wildlife populations are in decline, across multiple genera and species. The 2015 revised edition of the Wildlife Action Plan therefore places even greater emphasis on habitat conservation by providing summaries of priority actions that local Planning District Commissions can apply on a regional scale.

What can Master Gardener volunteers do at the local level to support the Wildlife Action Plan? Master Gardeners are in a unique position to influence the trajectory of habitat loss by increasing public understanding of this issue. Oftentimes, homeowners and landowners are either completely unaware of or only vaguely familiar with the connection between their landscape practices and the effects of those practices on habitat quality. Continued emphasis in our education outreach programs about good conservation landscaping practices is essential for raising awareness. If we provide consistent, clear messages and simple guidance about how to improve or restore habitat in our communities, then the resulting actions by the public should help to slow—and ultimately, one hopes, to reverse—the trend of declining wildlife species. Conservation begins at home and in the neighborhood, and habitat gardening is a good first step to restoring and sustaining biodiversity.

Habitat Principles

What Wildlife Needs: Vegetative (Biotic) Components

In order to understand fully what wildlife needs, we must begin with plants. Each plant species in a given geographic area has a total number of individual plants that make up a population, and the collection of plant populations found in that area form an assemblage known as the plant community. A diverse, healthy plant community provides multiple ecological services, such as interception of rainfall, which helps to recharge the groundwater and reduce flooding and erosion. Plant communities also contribute to nutrient cycling, oxygen exchange and carbon sequestration processes. Perhaps one of the most crucial functions of a plant community, in addition to these many benefits, is the life-sustaining support it provides to an associated community of wildlife species. The plant community provides organic matter for a variety of organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, and the plants also provide food and cover for wildlife, including birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and insects.

Plant and animal communities live and interact together in varying compositions and in distinct, often complementary relationships to each other. These biologically diverse communities, when combined together with the other non-living (abiotic) elements of the surrounding environment, such as soil, water and sunlight, form a functional system of continuous energy exchange called an ecosystem. Forests, wetlands and prairies are examples of ecosystems that contain thousands of plant and animal populations that interact with each other in the context of other landscape components.

Together, these interdependent populations of plants and animals make up countless communities within ecosystems, which give an area its species richness and genetic diversity. Biodiversity refers to the variety of genes, species and ecosystems in the aggregate, across the larger landscape.

A habitat is the area within an ecosystem where an animal is able to secure the food, water, cover and space it needs to survive and reproduce. Every wildlife species has specific habitat requirements; but because there are often overlaps of habitat features within a system, there are usually multiple wildlife species that can live in a given habitat. Salamanders, for example, require moist soil and rich organic matter that can be found in forest, riverine, and wetland ecosystems. Each of those ecosystems contain multiple habitat components—the tree canopy, boggy low areas, rocky outcrops, etc.—and other wildlife species like frogs and birds will be found in association with the habitats in those ecosystems, too. This means that if we want to restore and sustain biodiversity in the landscape around our home or on our property, we simply need to “put back” an assemblage of many of the plant species and other elements that would naturally have occurred there, and arrange the plants and those elements in such a way that many wildlife species will be able to take advantage of them and meet their needs for survival.

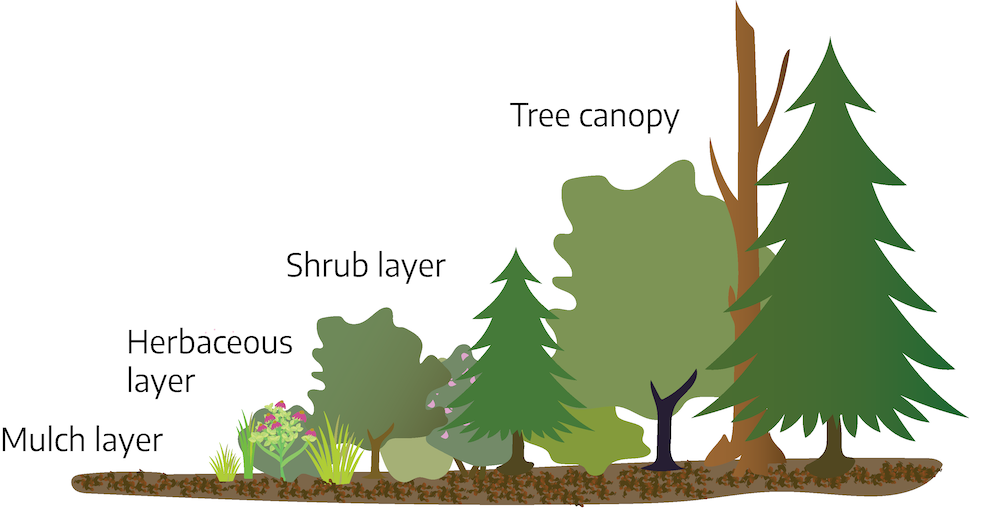

Habitat gardens are therefore most successful when they support a broad diversity of wildlife species, and the easiest way to achieve wildlife diversity is to choose a variety of plant species that most closely mimic the vegetative structure of a natural system. Plants are the living or biotic component of the landscape, and vegetative or vertical structure refers to layers of plants that provide a level of complexity and functionality in their arrangement such that they sustain a broad array of wildlife species.

Mulch layer

For example, on the ground plane of an eastern deciduous forest, the first component is the mulch layer, which forms a humus blanket that maintains soil temperature and can protect the ground from erosion. The mulch layer is critical for the decomposition process and supports many insects such as sow bugs, beetles and millipedes. These insects then become food for predatory insects such as centipedes and also serve to feed other wildlife, such as spiders, salamanders, toads, lizards, turtles, small mammals and birds. As the leaf litter and woody debris are broken down through the chewing and shredding of insects, along with the associated decay that’s wrought by fungi and bacteria, nutrients are released back into the soil, where plants can take them up again. This continuous recycling of organic matter and replenishment of soil is a most valuable aspect of the mulch layer. Therefore, one of the very first steps in establishing a habitat garden is to retain the leaf litter in the landscape, so as to support a rich assortment of organisms that will form the foundation for a complex food web.

Herbaceous layer

The next layer in our forest example is the herbaceous layer. These are plants with green, mostly non-woody stems, and they include species that form the groundcover layer. Groundcovers are plants that creep along the mulch or grow in clumps or masses and provide a protective covering for the soil below. Foamflower (Tiarella), wild ginger, striped wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata), sundrops, woodland phlox, columbine, and bluebells (Mertensia virginica) are some wildflowers or “forbs” we might see in the forest setting. In addition to these groundcover plants, the herbaceous layer may also contain a variety of ferns as well as vines, such as crossvine (Bignonia capreolata), pipevine (Isotrema macrophyllum), trumpet vine (Campsis radicans), and Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). Of special note is that groundcovers in nature are typically much taller than the two to three inches in height we’re accustomed to seeing in a conventional lawn. Hence, the herbaceous layer in a productive habitat garden is not likely to be a short carpet but rather a diverse composition of plants of varying heights that simply cover the ground.

Shrub layer

Standing above the herbaceous layer but below the taller trees is the shrub layer or “sub-canopy” layer. This layer is comprised of flowering shrubs that grow in a wide range of sizes, from as small as 2 feet for huckleberry or lowbush blueberry, to medium heights of 6-12 feet for deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), spicebush (Lindera benzoin), and viburnums, and as tall as 15 or 20 feet for American hazelnut (Corylus americana), witch hazel, and rhododendrons.

Tree canopy layer

Overhead is the canopy formed by the tallest plants, the tree layer. Some trees are small, only 20 to 35 feet in height, such as pagoda dogwood (Cornus alternifolia), paw paw (Asimina triloba), and redbud (Cercis canadensis). Others grow within a range of 30 to 60 feet in height, such as serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), and American holly (Ilex opaca). The largest trees, such as oaks and hickories, can attain heights of 80 to 100 feet.

Since most of our built landscapes are typically missing one or more vegetative layers, we can easily support more wildlife species by taking our cues from nature and choosing a palette of plants appropriate for our particular site conditions. For example, if the landscape is primarily wide open lawn, which is devoid of vegetative layers and diversity, we could bring life back to the scene by emulating a meadow habitat made up of sun-loving native grasses and flowers. If our landscape has some tree cover but little else, we could add a shrub layer and herbaceous ground covers. A very wet, boggy area in the yard that’s difficult to mow and maintain could be transformed into a mini-wetland, with the addition of common elderberry and buttonbush to make up the shrub layer, and moisture-loving plants like Joe pyeweed (Eutrochium purpureum), cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), and swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) to form an herbaceous layer.

Horizontal and vertical structure layer

Another habitat principle we can apply in our landscape planning is horizontal structure. Over the course of time, plant species within a given community will naturally change, if there are no interventions such as mowing, grazing or burning. Each stage of change occurs in succession after the one before it, and this process of succession is why a plant community that starts out as a meadow will gradually be replaced with woody species and eventually become a forest in the final stage. The arrangement and interspersion of these different successional stages in proximity to each other is what provides horizontal structure. We can use basic gardening and maintenance methods to improve horizontal structure by encouraging the growth of particular vegetative types that will mimic different successional stages, which in turn will support different wildlife species. For example, if we stop mowing an area, we can allow woody shrubs and trees to gradually take over and provide a forest-type habitat. If, on the other hand, we already have a woodland and want to attract wildlife species that require grasses and other flowering herbaceous plants, we can create an opening in the canopy and plant perennials and grasses, then keep the successional changes in check by mowing every two to three years, which will prevent woody vegetation from becoming re-established there.

We can also enhance the places where two habitat types come together, referred to as an edge. This transition zone is made up of plants from each of the habitats juxtaposed to each other and therefore contains wildlife species from both habitats as well. The greater the number and variety of plant species along an edge, the higher the abundance of wildlife found there. In a landscape setting, we can maximize this edge effect by increasing the number of plant species in the space between where two different vegetative types occur. For example, where a lawn abuts a stand of trees, we can add a shrub layer alongside the trees, to soften the edge. We could even take the edge one step further by adding a layer of herbaceous flowering plants next to the shrub layer. Hence, even a very small space like a townhouse yard can greatly increase its habitat potential by simply adding layers that improve both vertical and horizontal structure.

Similarly, the edges of small creeks and streams that run through the landscape can be enhanced or protected with vegetation. An edge of shrubs and trees planted along a waterway will provide a sheltering buffer for wildlife from human activity, and the roots of the plants will hold the soil and filter runoff that enters the stream – thus improving the aquatic habitat within the stream, too.

Choosing Plants for Wildlife: Interrelationships and Biodiversity

Now that we know how to put a habitat together—arrange it in layers, with lots of structure and diversity—the next step is deciding which plants to use. There’s an important case to be made for selecting native plants for wildlife whenever possible.

What’s a native plant? According to the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, “Native species are those that occur in the region in which they evolved. Plants evolve over geologic time in response to physical and biotic processes characteristic of a region: the climate, soils, timing of rainfall, drought, and frost; and interactions with the other species inhabiting the local community.”

Mounting scientific evidence indicates a strong correlation between the use of native plants in the landscape and insect biodiversity.

According to researchers Desirée L. Narango, Douglas W. Tallamy, and Peter P. Marra, “Over 90% of herbivorous insects specialize on one or a few native plant lineages—thus, ecosystems dominated by nonnative plants are characterized by reduced insect diversity, abundance, and biomass. Given that the majority of terrestrial birds rely on insects as a primary food source for reproduction and survival, the persistence of insectivorous bird populations is inextricably linked to insect conservation,” (2018). The choice of plants we make in our landscape not only impacts the biodiversity of insect populations but also multiple bird populations as well. Further, Tallamy and other scientists have found that not all native plants are equally productive. Some plant species support far greater biomass or numbers of organisms than others. For example, native plants in the Lobelia genus (such as cardinal flower) only support four species of Lepidoptera (butterflies, moths and skippers), while plants in the Carex genus (the sedges) support 36 species of Lepidoptera.

As gardeners, then, we have a wide range of choices before us when selecting plants for habitat improvement. The initial decisions we make for habitat gardening will likely be the same as for any other project, based on three primary factors: 1) how we plan to use the site; 2) the current site conditions; and 3) what plant species are most appropriate for those site conditions and the geographic region we live in. Budget is typically a fourth factor. Although it’s true that the more native plant species we use, the better the wildlife diversity will be, it’s important to find the right balance to suit our specific site, which is an individual choice that will depend on our own particular needs. Ultimately, the degree to which one is able to improve habitat and sustain wildlife will be unique to each situation and dependent on individual preference.

In addition, there are many other reasons to use native plants besides the benefit of providing food and cover for wildlife. Whenever we choose “the right plant for the right place,” we ensure a more successful outcome, especially if we select those best adapted for drought—or water-tolerance. And although native plants are not maintenance free—contrary to popular opinion—they can substantially decrease long-term maintenance requirements over time, once established. In general, native plant landscapes use less water, help reduce energy costs, and can increase property value because of their intrinsic aesthetic appeal.

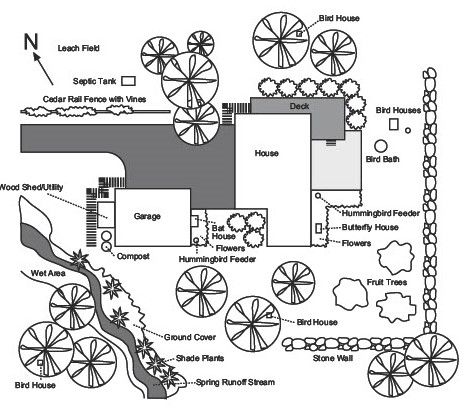

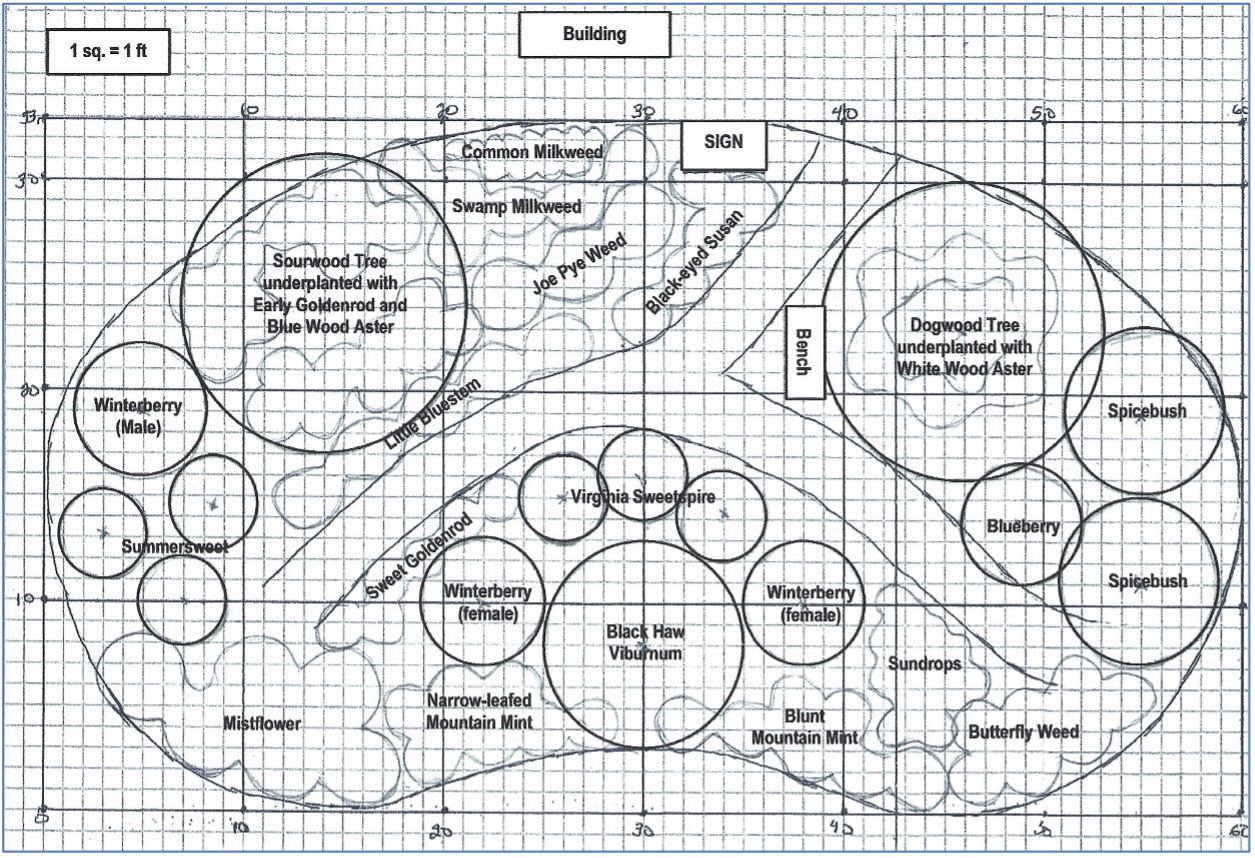

Goochland-Powhatan Extension Master Gardener Habitat Demonstration Garden

By Linda Toler, Extension Master Gardener, Goochland-Powhatan

In 2021, Extension Master Gardener volunteers from the Goochland-Powhatan Master Gardener Association (GPMGA) initiated a project called “HOPE from the Garden” (HOPE stands for Helping Our Planet Endure) to encourage gardeners to adopt practices that will help keep the land healthy and support the life that depends on it, keep local waters clean and plentiful, and keep the air clean and unpolluted.

The initiative focuses on these areas:

- Building and maintaining a healthy soil.

- Minimizing the use of pesticides.

- Reducing lawn areas.

- Incorporating native plants into our landscapes and eliminating invasive plants.

- Providing healthy wildlife habitats.

- Conserving water.

- Managing stormwater runoff.

- Adopting gardening practices that contribute to clean air.

Some of the specific recommendations within each area are “no-brainers,” while others like no-till gardening and reducing lawn areas, may require a change in thinking for some gardeners. Some may ask, “is it even possible to have an attractive landscape that adopts these practices?”

Goochland-Powhatan Extension Master Gardeners believe the answer is “yes.” And so, in late Fall 2022, a team of GPMGA volunteers began installation of a “HOPE Garden” in a large, sunny, lawn area in front of the county building housing the Goochland County Extension Office and others.

The main practices illustrated by the garden are:

- Conversion of a lawn area into an ecologically beneficial garden using no-till gardening techniques.

- Design of an attractive garden of native plants that provides value to wildlife.

- Maintaining a garden without the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and gasoline-powered equipment.

In Fall 2022, garden installation began using a no-till, “lasagna garden” approach. Plentiful fall leaves and grass clippings were layered over sheets of cardboard, wet down, and left to break down over the winter months.

Plant installation began the following spring. Plants selected for the garden are native to Virginia’s Capital Region, are attractive in the home landscape, and most importantly, support the invertebrates, birds, and mammals that are so important to our local ecosystems. For example, the native dogwood (Cornus florida) included in the design is the larval host for 115 native caterpillar species. The design includes trees, shrubs, and perennials selected to provide garden interest throughout the year. Each plant was selected for the teaching opportunities it presents. Other features to support wildlife will be added as the garden evolves.

The garden is laid out with pathways for up-close viewing of the plants and their “visitors.” Educational signage describing the plants and their benefits to our native ecosystem are planned as are educational events and activities for homeowners and children.

The “HOPE Garden” is a new project that will evolve over time. The volunteers are excited about providing a forum for presenting the positive benefits of converting part of a lawn area into an attractive native plant garden that will help support our native wildlife.

To initiate a project like this in your community, find a location that has visibility in the community, get buy-in from key stakeholders, decide what you want to teach with the garden, and line up a team of hard-working volunteers who are committed to the project and sharing the concepts with the community.

Conservation Landscaping and Habitat Gardening

Conservation landscaping refers to landscape principles that apply best practices for conserving water, soil, and existing native plant communities. The Chesapeake Conservation Landscaping Council has developed simple guidelines that can help homeowners, landowners, landscape professionals and municipal decision-makers take action to improve the health of the Chesapeake Bay watershed. However, these guidelines can certainly be applied to other areas of the state that are outside the Bay watershed, because conservation practices help improve environmental quality no matter where we live.

The “Eight Essential Elements” are useful for making informed landscape choices. A conservation landscape:

- Is designed to benefit the environment and function efficiently and aesthetically for human use and well-being;

- Uses locally native plants that are appropriate for site conditions;

- Institutes a management plan for the removal of existing invasive plants and the prevention of future nonnative plant invasions;

- Provides habitat for wildlife;

- Promotes healthy air quality and minimizes air pollution;

- Conserves and cleans water;

- Promotes healthy soils;

- Is managed to conserve energy, reduce waste, and eliminate or minimize the use of pesticides and fertilizers.

Conservation landscaping is therefore a systematic approach that integrates the use of native plants and wildlife habitat into our built environment while simultaneously reducing the need for mowing or for using fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, water and fossil fuels. With this approach, plants are selected not just for their ornamental appeal but for their function in providing the highest habitat value for the site, in order to sustain multiple wildlife species. There’s much less emphasis on using turfgrass as the predominant cover type, because turfgrass supports very little biodiversity. Instead, the principles apply greater emphasis on replacing lawn with assemblages of native plants that would be found locally in the natural environment. In essence, a conservation landscape sustains life and conserves resources in a way that traditional landscaping often does not. Yet, conservation landscapes can provide as much—and many would say they provide more—beauty and aesthetic appeal to the human eye.

After the vegetative components have been chosen and the various layers of plants have become established, it’s time to look around the landscape and strategically fill in any remaining spaces with additional structural components that will augment the available habitat for wildlife. These are the non-living or abiotic elements of the landscape. The most commonly used structural components include brush piles and rock piles, snags (dead trees), nest boxes, areas with bare soil, and water features.

Table 18-2: Examples of Conventional Landscaping Practices that Reduce or Increase Habitat Value

| Examples of Conventional Landscaping Practices that Reduce Habitat Value | Examples of Conservation Landscaping Practices that Increase Habitat Value |

|---|---|

| Select plants primarily for their perceived decorative value, unusual physical characteristics, or rapid growth habits that will quickly and easily fill in a site, regardless of where the plant species originated. | Select plants primarily for their utility to wildlife, water quality and ecosystem processes, in order to emulate native plant habitats that would be found naturally in the local region and are most appropriate for the given site conditions. Avoid selecting non-native “alien” or “exotic” invasive plant species known to be problematic in the environment, and control these plants if they enter the landscape, in order to reduce the likelihood of their competition with native plant communities. |

| Maximize lawn as a predominant feature of the landscape. | Minimize lawn by using it artistically where needed, for its specific functional value, such as for a pathway, or for certain recreational activities, or to frame a view or provide an intentional edge around a planted bed. |

| Routinely apply fertilizer and pesticides to optimize plant growth. | Use native plant species that are well-adapted to local soils, climate and insect predation, thereby reducing or eliminating the need for fertilizers or pesticides, which can run off the site during a rain event and have harmful effects on water quality and aquatic wildlife species. |

| Rake-up and bag-up leaves in autumn, and dispose of in the landfill. Remove and dispose of all downed twigs, branches and other woody debris. | Keep leaves on site by shredding and/or composting them, and use the material for mulch and/or as an organic amendment to ornamental planting beds, which will enrich the soil and provide a sustainable food source for insects and other wildlife. Keep downed twigs and branches on site by chipping them and composting the material or using it for mulch, or cut the larger branches into manageable sizes that can be used to create brush piles for wildlife cover. |

| Remove all dead vegetation from flowering plants in the fall. | Allow dead vegetation to remain on site throughout winter (until late February/early March), which will provide cover for dormant insects or their eggs, and places for birds to feed and seek protection from harsh weather. Design the landscape such that plant species are strategically chosen and placed to provide interesting structural elements in winter dormancy, and therefore greater visual and aesthetic interest throughout the season. |

| Mow all the vegetation along a creek or stream, down to the water’s edge. | Maintain at least a 35 foot buffer of plants such as shrubs and trees along waterways, which will filter runoff from the surrounding land, will shade the water, and will keep the soil from eroding the banks, thereby protecting aquatic wildlife species that cannot tolerate extremes of water temperature and that need clean water to thrive. |

Brush Piles and Rock Piles

Brush piles and rock piles provide places for wildlife to seek shelter from the elements of rain, wind and snow over the course of a year. The “nooks and crannies” afford cool, dark areas to hide from the summer sun, or a protected spot to nestle down and retain warmth against the winter’s chill. Temperature extremes aside, these simple constructed piles of easily found materials also provide valuable escape cover from predators, as well as places for wildlife to raise young. Rabbits, raccoons, mice, chipmunks, box turtles, lizards, snakes, insect-eating birds are just some of the many other animals that seek out these protected areas from time to time, either to rest, find food, overwinter or lay their eggs. Depending on how big the pile is, some species may create a burrow or nest underneath the pile to live on a more permanent basis.

The limiting factor for brush piles and rock piles, of course, will be the size of the yard, as these piles are best suited to fairly large size lots (at least an acre), with plenty of space. It’s also important to locate the pile well away from buildings and vegetable gardens, in order to minimize the likelihood of attracting wildlife such as groundhogs or skunks, which might decide to seek alternative shelter under the foundation of a nearby house or shed. Very small yards, such as a courtyard or a town house lot, are not conducive to making a pile at all.

Rock piles can be placed on the edges of the property near existing vegetation, or behind a shrub bed or adjacent to a stand of trees—wherever the rocks will blend in with the surrounding landscape to look natural and not too contrived. A rock pile can also benefit frogs and other aquatic organisms when stacked loosely among the vegetation next to a creek or a pond, or partially submerged at the water’s edge, at least a foot below the water’s surface.

To build the pile, choose rocks or old bricks and blocks of various sizes and shapes, ranging from potato size to soccer ball size for the home landscape setting, or larger sizes in the more rural, spacious setting. Arrange the rocks unevenly, with open spaces between them, to fill an area at least five or six feet wide and one or two feet deep. Don’t worry about being too artistic with rock placement. Wildlife doesn’t care how pretty it looks; they just want a place to hide when the time comes. Consider planting a ground cover around the edges of the rock, or a vine that will grow over it, to provide additional protection. No need to mow there anymore!

Similarly, a brush pile is loosely constructed with lots of open spaces between the branches, which will make it easier for a wren to fly in or a rabbit to run under when threatened. Although a brush pile can be messy and built as big and wide as you like, avoid dumping a big pile of debris on the ground, which is a practice more suited to starting a compost heap. Rather, build the foundation of the brush pile in the manner of a miniature log cabin, starting with stumps or small logs, depending on what you have on hand, and criss-cross these in a couple of stacks until you have a firm base, preferably on level ground. Then stand large tree limbs up against the base, stacked against it, with the butt ends of the branches on the ground, and the thinner, lighter tips pointing up above. This will form a somewhat pyramidal-looking structure that you can continue to add smaller branches to, until most of the interior is no longer visible, but with plenty of empty voids remaining throughout the stack. Place the greatest number of branches on the side of the pile that faces the prevailing winds, to ensure additional protection from summer thunderstorms and winter winds.

Effective brush piles are quite large. In a rural landscape or on a very large lot, they should be at least 12 to 15 feet in diameter and at least five or six feet tall. However, this may not be practical for a smaller suburban lot. A smaller pile, such as six to eight feet wide and four to five feet tall, may be more appropriate for a residential setting and should still be adequate for many wildlife species to use.

Snags

Another structural component that some would say is “worth its weight in gold” for wildlife is a dead tree or snag. Dead trees provide a cornucopia of benefits, because the decaying material is host to innumerable insects and their larvae that chew their way through the wood or otherwise feed beneath the bark. Approximately 30 percent of native bee species use abandoned beetle tunnels in dead trees as a nesting site to lay their eggs. This abundance of burrowing insects, grubs and eggs provide an invaluable protein source for dozens of bird and mammal species. Woodpeckers make their homes in dead trees, too, and the holes they leave behind in the trunk and the branches provide places for bluebirds, chickadees, nuthatches, tree swallows, screech owls, titmice, opossums, tree squirrels, bats, raccoons and other cavity-seekers to raise their young. Snags provide open perches for hawks to hunt from, and when dead trees are located near a water body, kingfishers, flycatchers and herons can hunt from these perches as well. Other birds use snags as a convenient post to sing from when proclaiming their territory. Dead trees also provide a refuge for birds and hibernating mammals in winter, when fewer resources for cover may be available in other parts of the landscape. In a pond environment, a fallen tree in the water can provide excellent habitat structure for fish and other aquatic species.

The astonishing array of wildlife species that rely on dead trees—and on decomposing logs and branches on the ground—cannot be overstated. Therefore, whenever possible, leave dead trees standing. If a dying or dead tree poses a threat to a walkway, driveway or building, the tree can be taken down and left on the ground to decompose naturally and become an interesting if not unusual focal point, especially if it’s used as a backdrop for planting flowers and ferns around it. Or, sections of the tree can be cut up and used to make a brush pile, as described earlier. Either way, retaining dead trees and woody material on site will greatly enhance the habitat value for wildlife and also recycle nutrients back into the soil.

Nest Boxes

Birds

Where no dead or dying trees are present, the next best thing is to put up nest boxes for cavity-seekers. Nest boxes provide vital homes for birds and small mammals such as flying squirrels to bear and raise their young, and each species that uses them has different requirements for the box dimensions, including the overall size of the box, the diameter of its opening, and the depth of the cavity within.

There are several considerations for constructing a bird house. Use untreated wood and select rough-cut lumber that’s a minimum of ¾- inch thick (one inch is better). Cedar is a good choice, if available, because of its durability. The box should provide for adequate ventilation near the top, for heat to escape, and holes in the bottom for drainage, if water gets in. The roof of the box should overhang the front, to keep rain from entering, and the box should also have a provision for opening up the side or the top to clean out the contents at the end of the breeding season. Roughen the inside of the front part of the box, or attach a small piece of hardware cloth to it, to make it easier for young birds to climb out when it’s time for them to fledge; do not paint the inside of the box. Also, do not attach a perch to the outside of the box, which merely provides an easier foothold for predators and encourages other non-native birds like starlings and house sparrows to attempt to enter.

To install a bird house, place it on a free-standing post or pole, well away from trees, which are the domain of the black rat snake. Secure a conical or stovepipe-type baffle to the post or pole beneath the box, in order to discourage raccoons, snakes and other predators. Do not use grease on the pole, as this is an unreliable method for deterrence and may sicken animals which ingest it. Be sure the front of the box is directed away from the prevailing winds, but face the box towards a distant tree where young birds can land when they leave the nest.

Table 18-3: Examples of Common Nest Box Dimensions

Various sources may recommend different dimensions. More detailed specifications for constructing nest boxes are available from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

| Bird Species | Diameter of Entrance Hole (inches) | Depth of Cavity (inches) - from bottom of hole to the floor of the box | Floor of Cavity (inches x inches) | Height of Box Above the Ground (feet) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Bluebird | 1.5 | 6.5 | 5 x 5 | 5-15 | Place in open areas away from buildings and spaced 100 feet apart |

| Carolina Chickadee | 1.125 | 8 | 4 x 4 | 5-15 | Place in area with mature hardwoods |

| Northern Flicker | 2.5 | 16-18 | 7 x 7 | 8-10 | Fill box with sawdust |

| House Wren | 1 | 6-8 | 4-6 | 5-10 | This species will fill the nest box with sticks |

Bats

Bat houses are constructed very differently than bird houses. A bat house has no floor on the bottom, because bats fly in and out from below, and the interior of the box is made up of several narrow partitions, conducive to the bats hanging between the baffles. The species that most commonly use bat houses in the mid-Atlantic region are the little brown bat and the big brown bat; females of these species congregate in nursery colonies in the summertime and may use boxes to raise their young. However, success with bat houses is mixed and seems to depend on many variables, such as the numbers of partitions within the box and the width between them; or how much sun the box receives (it should be painted a dark color to absorb sunlight, because bats need warm temperatures); or how far above the ground the box is mounted (typically 12 to 20 feet). Boxes placed in proximity to a natural water source, such as a pond, lake, stream or river, are often said to have the greatest success of use, because bats frequent aquatic areas where insect numbers are typically high. Place bat houses on the side of a building away from nighttime lights, and orient the box towards the southeast for maximum exposure to sunlight in the early morning. Instructions for building a bat house are available online, here is one example from the U.S. Forest Service: “Building a Bat House.”

Bees

Another type of nesting house is one that can be made for orchard mason bees, which seek out holes or tunnels in plant stems to build brood cells in which to lay their eggs. Make the bee nest house from plants that have hollow stems, such as reed grass or teasel. If there happens to be a stand of invasive bamboo available, select narrow stems approximately half inch or less in diameter and cut them into five or six inch lengths. Then hollow out about three and a half inches on the end of each stem, leaving part of the tube closed. Gather about 10 to 15 of these pieces, tie them into a bundle with the closed ends together, and hang the bundle horizontally from a tree or building about three to six feet off the ground, in a sunny area with the holes facing east or southeast, and sheltered from the elements.

Or, make a “bee block” by drilling a series of holes between 3/32 and 3/8 inch in diameter, about ¾ inch apart on center, into an untreated (preservative free) block of wood, or into an old log or stump. Do not drill all the way through but rather only three to four inches deep, for holes less than ¼ inch diameter, or five to six inches deep for holes larger than ¼ inch.

Areas with Bare Soil

Bare soil is often an overlooked element in the landscape that can be useful for some wildlife species. Songbirds will appreciate an occasional dust bath where bare soil is available, in order to control mites and other external parasites on their skin or in their feathers. Birds also ingest bits of grit and coarse sand, which help to grind up food such as hard seeds in the bird’s gizzard. A simple way of providing the dust they need is to scrape away the vegetation from a two to three foot diameter patch of ground and allow it to dry out.

Areas of bare ground are also extremely important to bees, because almost 70 percent of North America’s 4,000 native bee species nest in the ground. These are solitary-nesting bees, which means that individual females seek out their own nest site to tunnel into the ground. Since the soil surface should be bare in order to provide bees the access they need to dig, a good rule of thumb is to clear small patches of bare ground in a sunny, open space, up to a few feet across, and pat the areas firmly to compact the surface. Different locations will attract different bee species; therefore try clearing patches on both flat ground and on slopes, particularly those that are facing south.

Bare ground can also be supplemented with sand pits for bees. Find a sunny spot, dig a hole in the ground about two-feet deep, and fill it with a mix of sand and loam that will provide good drainage.

Water Features

Another structural element that’s essential to any habitat garden is the presence of water, which can be provided in many ways. Bird baths are perhaps the easiest and can be purchased in a variety of shapes and sizes. Choose a bird bath with a shallow basin that has gradually sloping sides and is no more than two or three inches deep. Put one or two fist-sized stones into the water where birds can land, and place the bird bath several feet away from a shrub or tree, so that birds can easily seek cover if needed. To extend the season for year-round bird use, install a small heating element that will keep the water from freezing in winter.

An even simpler way of creating a bird bath is to turn the lid of an old trash can upside-down and nestle it within a plant border, or use a large, plastic plant dish the same way. Regardless of size or type, replenish all bird baths with fresh water every few days throughout the summer, to keep mosquitoes from breeding there.

Creating small mud puddles for insects is another method of providing water. Butterflies in particular use wet patches of soil (or wet manure) to obtain minerals, and this “puddling” behavior is commonly seen along the muddy edges of roads after a rain storm. To replicate a small mud puddle, fill a shallow cake pan with a mixture of sand and soil, fill it with water, and place it in a sunny area near a flower bed.

There may also be opportunities in the landscape to capture and divert a portion of the rainwater that falls and to collect it in a shallow depression to create a mini-wetland. Unlike a true rain garden, which is constructed several feet deep with permeable soil and is designed to hold water for no more than four days, the mini-wetland is only about 12 to 15 inches deep and is lined with a layer of clay at the bottom to hold the water for a longer time. The depression is filled with a soil mixture that contains mostly loamy organic matter and a bit of clay, then it’s planted with species that are adapted for periodic inundation—hence the habitat. Locate this water feature in a low-lying area where water already naturally collects.

Or, construct the mini-wetland approximately 10 feet away from a building where it will receive some of the water from a downspout, with the aid of a shallow, planted swale that directs the water from the downspout to the area below. One can also connect a flexible plastic pipe to the downspout and bury it in the ground, with the end of the pipe daylighting directly into the clay-lined depression. However, be sure there’s enough slope between the building and the water feature, so that the pipe doesn’t back up during a heavy downpour.

These examples are simple ways of providing water for terrestrial wildlife species to use for drinking or bathing. A water garden or frog pond provides a larger habitat for aquatic species to live and breed in and is discussed in the section below, “Water Garden for Frogs, Salamanders, and Other Aquatic Species.”

Table 18-4: Selected native shrubs for wildlife habitats

Source: USDA-NRCS (2014). Field Office Technical Guide, Section 2, Plant Establishment Guide. [NOTE: This shrub list is excerpted and adapted from a much larger database.]

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height (feet) at 20 years | Not Preferred by Deer | Fruit / Seed Abundance | Value to Pollinating Insects | Bloom Period | Shade Tolerance | Anaerobic (wet) Soil | Drought Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highbush Blueberry | Vaccinium corymbosus | 6 | High | High | Spring | Tolerant | Medium | Medium | |

| Buttonbush | Cephalanthus occidentalis | 15 | Medium | High | Summer | Tolerant | High | Medium | |

| Eastern Red Cedar (evergreen) | Juniperus virginiana | 20 | x | Medium | High | Late Spring | Intermediate | Low | High |

| Black Chokeberry | Photinia melanocarpa | 15 | x | Medium | Moderate | Spring | Tolerant | Medium | Medium |

| Red Chokeberry | Photinia pyrifolia | 5 | x | Medium | Moderate | Mid Spring | Intolerant | Medium | Low |

| Coralberry | Symphoricarpos orbiculatus | 2 | x | High | Low | Mid Spring | Intermediate | None | Medium |

| Southern Crabapple | Malus angustifolia | 30 | x | High | High | Mid Spring | Intolerant | Low | Medium |

| Flowering Dogwood | Cornus florida | 20 | Medium | Low | Early Spring | Tolerant | None | Low | |

| American Black Elderberry | Sambucus nigra, ssp. canadensis | 7 | x | High | Moderate | Spring | Intolerant | Low | Medium |

| White Fringetree | Chionanthus virinicus | 20 | High | Low | Mid Spring | Tolerant | Low | Medium | |

| Cockspur Hawthorn | Crataegus crus-galli | 30 | High | High | Late Spring | Intolerant | None | High | |

| American Holly (evergreen) | Ilex opaca | 20 | x | Low | High | Mid Spring | Tolerant | Low | Medium |

| Winterberry Holly | Ilix verticillata | 6 | x | High | High | Late Spring | Intermediate | High | Low |

| Indigobush | Amorpha fruticosa | 6 | x | High | High | Late Spring | Intolerant | None | Medium |

| Common Ninebark | Physocarpus opulifolius | 10 | High | Moderate | Late Spring | Intolerate | None | High | |

| Pawpaw | Asimina triloba | 25 | x | Medium | Low | Mid Spring | Tolerant | Low | Low |

| American Plum | Prunus americana | 24 | x | Medium | Moderate | Mid Spring | Intolerant | Medium | High |

| Chickasaw Plum | Prunus angustifolia | 12 | x | Medium | Moderate | Early Spring | Intolerant | None | None |

| Eastern Redbud | Cercis canadensis | 25 | Medium | High | Spring | Tolerant | None | High | |

| Swamp Rose | Rosa palustris | 8 | Medium | Moderate | Spring | Intolerant | High | Low | |

| Canada Serviceberry | Amelanchier canadensis | 20 | x | High | Moderate | Mid Spring | Intermediate | Medium | Low |

| Northern Spicebush | Lindera benzoin | 12 | x | Low | High | Mid Spring | Intermediate | Medium | Low |

| Strawberrybush | Euonymus americanus | 8 | Medium | Low | Late Spring | Intolerant | Low | None | |

| Smooth Sumac | Rhus glabra | 12 | High | Moderate | Mid Spring | Intolerant | Low | Medium | |

| Winged Sumac | Rhus copallinum | 8 | High | Moderate | Mid Spring | Intolerant | Medium | Medium | |

| Eastern Sweetshrub | Calycanthus floridus | 7 | x | Medium | Low | Summer | Intolerant | Low | Low |

| Blackhaw Viburnum | Viburnum prunifolium | 16 | x | Medium | Moderate | Spring | Tolerant | None | Medium |

| Southern Arrowwood Viburnum | Viburnum dentatum var. dentatum | 15 | x | Medium | Moderate | Early Spring | Intermediate | None | Low |

| Silky Willow | Salix serricea | 12 | Medium | High | Mid Spring | Intermediate | High | Low |

Selected Habitat Gardens that Sustain Wildlife Diversity

Habitat Garden for Butterflies and Other Pollinators

One of the most popular, visually-rich landscaped habitats is a garden designed specifically to support pollinators. Pollinators are wildlife species that move pollen from the flowers of male plants to the flowers of female plants of the same species, when the pollinator travels from flower to flower in search of nectar, pollen or other insects to eat. Pollinators include hummingbirds, butterflies, moths, bees, wasps, beetles, flies and some species of bats. Their role is to help fertilize female plants and enable the plants to produce seeds, nuts or other fruit. These animals are therefore critical for ecological function. Without pollinator services, plants would not be able to survive reproductively, because over 85% of flowering plants require an animal—usually an insect—to move pollen (Ollerton et al., 2011), and over 25% of the global diets of birds and mammals are comprised of pollinator-produced fruits and seeds (Adamson 2016). Our agricultural industry is also heavily reliant on pollinators to produce the high yielding crops we’ve come to expect in food production. “In 2009, it was estimated that honey bees contributed USD 11.68 billion to agriculture in the U.S.” (Calderone, 2012). In Virginia, bees are attributed with supporting $23 million of the apple industry (McBryde, 2016).

Restoring a site by replacing lawn with pollinator habitat can transform the landscape, because as the new plants become established and begin blooming, insects of all types very quickly descend on the flowers, seemingly from out of nowhere. To plan a pollinator garden, as with any other kind of habitat garden, it’s helpful to remember that each group of organisms has different requirements. When we attempt to select plants for butterflies, we need to think of butterflies as if they’re “two animals in one,” because of their metamorphic life cycle. A butterfly start outs as an egg, develops into a caterpillar that must eat leaves, and then after several stages and successive molts, it forms a chrysalis and develops into an adult, which must get its energy from flower nectar. Hence, to be successful, a butterfly garden must include host plants for the larvae and nectar plants for the adults. For example, the larvae of monarchs need milkweed leaves, while the adults can forage among numerous nectar-producing plants. If the only plants we select for a garden are the ones that simply provide a colorful bed of blooms, then we will have missed half the equation, and the overall habitat value for butterflies will be lower as a result.

A tremendous number of butterfly species rely heavily on tree species as host plants. For example, black cherry trees support swallowtails, painted ladies and luna moths, and black locust trees support sulphurs and skippers. Elm is the host plant for mourning cloak butterflies, willow is the host for tiger swallowtail, and hackberry tree for question marks. Based on the work of Narango et al. 2020, and Tallamy 2007, the following list of 20 woody plant genera includes trees and shrubs ranked by their value for supporting Lepidoptera (the classification of butterflies, moths and skippers). The list is based on an exhaustive search of the scientific literature about host plant ecology. Below are the top 10 tree genera for supporting Lepidoptera:

Ten most valuable woody native plant genera for supporting lepidoptera:

- Quercus (oaks) support 534 species of Lepidoptera

- Prunus (cherries) 456 species

- Salix (willows) 456 species

- Betula (birches) 413 species

- Populus (poplars) 368 species

- Malus (crabapples) 311 species

- Vaccinium (blueberries) 288 species

- Acer (maples) 285 species

- Ulmus (elms) 213 species

- Pinus (pines) 203 species

Most valuable ornamental native perennial plant genera for supporting lepidoptera:

- Solidago (goldenrods) support 115 species of Lepidoptera

- Aster (asters) 112 species

- Helianthus (sunflowers) 73 species

- Eupatorium (pyeweeds, boneset) 42 species

- Ipomoea (morning glories) 39 species

- Carex (sedges) 36 species

- Lonicera (honeysuckles) 36 species

- Lupinus (lupines) 33 species

- Viola (violets) 29 species

- Geranium (geraniums) 23 species

- Rudbeckia (coneflowers) 17 species

These data clearly indicate that butterfly species—indeed, whole populations of butterfly species—are dependent on hundreds of species of trees, shrubs and perennial flowers. We would therefore do well to select several trees, shrubs and flowering plants from the above groups when planning our pollinator garden, knowing that when we do, we’ll have all our bases covered, because the myriad connections between all those groups will ensure a high likelihood of a biodiverse habitat.

In addition to Tallamy’s work, other scientists are also conducting field research to further document the association between pollinators and specific plant species. In Pennsylvania, for example, Connie Schmotzer at Penn State Extension devised a series of “Pollinator Trials,” in part to evaluate “the level of insect attractiveness of various perennial plant species or cultivars.” The study monitored “88 pollinator-rewarding herbaceous perennial plants,” to see how many and what type of insect pollinators would seek them out. Below is a synopsis of some of the study results:

Best Plants for Pollinator Visitor Diversity (ranked in order of preference, out of 88) (Schmotzer and Ellis, 2014):

- Clustered Mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum)

- Coastal Plain Joe Pyeweed (Eupatoriadephus dubius)

- Stiff Goldenrod (Solidago rigida)

- Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

- Gray Goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis)

- Rattlesnake Master (Eryngium yuccifolium)

- Flat Topped Aster (Doellingeria umbellata)

- Spotted Joe Pyeweed (Eupatoriadelphus maculatus ‘Bartered Bride’)

Best Plants for Sheer Number of Bee and Syrphid [Fly] Visitors (Schmotzer 2013) (Numbers indicate the mean number of bees/syrphids observed per plot in 2 minutes):

- Clustered Mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum): 19 bees/syrphids

- Gray Goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis): 14 bees/syrphids

- Pink Tickseed (Coreopsis rosea): 14 bees/syrphids

- Lance-Leaved Coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata): 13 bees/syrphids

- Spotted Joe Pyeweed (Eupatoriadelphus maculatus ‘Bartered Bride’): 12 bees/syrphids

- Rattlesnake Master (Eryngium yuccifolium): 12 bees/syrphids

Best Plants for Attracting Butterflies (Schmotzer 2013) (Numbers indicate the mean number of butterflies/skippers observed per plot in 2 minutes:

- Coastal Plain Joe Pyeweed (Eupatoriadephus dubius): 17 butterflies/skippers

- Blue Mistflower (Conoclinium coelestinum): 5 butterflies/skippers

- Showy Aster (Eurybia spectabilis): 4 butterflies/skippers

- Sweet Joe Pyeweed (Eutrochium purpureum subsp. maculatum ‘Gateway’): 3 butterflies/skippers

- Dwarf Blazing Star (Liatris microcephala): 3 butterflies/skippers

As one can see, certain plants are like powerhouses when it comes to supporting pollinators. Therefore, all one needs to do to have a highly productive pollinator habitat is to start with the above top genera [goldenrods (Solidago); milkweed (Asclepias); tickseed (Coreopsis); mountain mint (Pycnanthemum); pyeweed (Eupatorium or Eutrochium); asters (Eurybia); mistflower (Conoclinium); and blazing star (Liatris)], and then look at the Virginia regional native plant list for the garden area in question, in order to determine the particular species of goldenrod, milkweed, tickseed, pyeweed, or aster. that would be most suitable for the given site conditions.

Moreover, not only do these represent a broad spectrum of species and flowering types, they also bloom at different times throughout the season, which adds a temporal dimension to the association of insects that will frequent the plants. For example, peak bloom time for mountain mint is mid-June to mid-July; for swamp milkweed, mid-July to mid-August; and for pyeweed, mid-August to early September. This means if we select a variety of plants across flowering times, in addition to selecting across genera, we can magnify the habitat benefits even more. A good rule of thumb is to “provide blooming plants from early spring to fall, with at least three species of flower in bloom each season” [Xerces Pollinator Conservation Fact Sheet].

In addition to the genera listed above, other excellent pollinator plants include those in the coneflower (Rudbeckia), beardtongue (Penstemon), phlox (Phlox), bergamot (Monarda), and ironweed (Vernonia) genera. Flowering perennials such as these, combined with native warm-season grasses to form meadows in large open settings, will provide early successional habitat that benefits many bird species as well. Some native warm-season grasses suitable for dry, sunny meadows are the following: big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Andropogon scoparius or Schizachyrium scoparium), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum).

Looked at another way, if landscape diversity is currently low in the built-environment around us, and if we add more forestal and meadow-like components (i.e., a diversity of shrubs, trees, grasses, and flowering perennials), then we’ll be supporting the butterfly species that are associated with each of those vegetation types.

An established pollinator habitat garden or meadow should be allowed to stand throughout the dormant months in fall and winter to provide winter cover. Mowing a pollinator garden is rarely necessary, and typically this practice is reserved for larger landscapes where the predominant vegetative type is native warm-season grasses, which are either burned or mowed only once every three years, to keep the thatch on the ground from becoming too thick. There’s a fairly short window of time for mowing or burning these rural fields, usually between mid-February to mid-March, which is at the end of winter, when insects have been dormant in the dead vegetation, but before birds begin nesting in the spring.

Here are some additional pollinator habitat tips from the Xerces Society:

- “Avoid pollen-less cultivars and double-petaled varieties of ornamental flowers.”

- Butterflies need warmth in order to fly; therefore plant pollinator habitats in open, sunny areas.

- Shelter pollinator habitats from the wind with some type of cover, such as groups of shrubs or hedgerows, trees, or a nearby wall or fence.

- Include some tall grasses in the habitat, allow the grass to remain overwinter, and conserve dead leaves and sticks in small piles. Caterpillars will use the grasses and brush piles to seek safety to build a chrysalis.

- Avoid cleaning out leaves and garden debris in the weeks leading up to the first severe cold spells of winter, because butterflies overwinter (hibernate) in the debris, either as eggs, larvae, pupae or even adults, depending on the species.

- Do not use insecticides in or near the garden, especially neonicotinoids, which “are systemic chemicals absorbed by plants and dispersed through plant tissues, including pollen and nectar.”

Butterfly Species Associated with Forest, Field, and Forest/Field Intergrade (Maria Van Dyke, Native Bee Research Lab, Dept. Entomology, Cornell University):

Forest:

- Zebra Swallowtail

- Easter Tiger Swallowtail

- Spicebush Swallowtail

- Pipevine Swallowtail

- Common Blue

- Question Mark

- Eastern Comma

- Mourning Cloak

- Red Spotted Purple

Field:

- Black Swallowtail

- Cabbage White

- Clouded Sulphur

- Orange Sulphur

- American Copper

- Eastern Tailed Blue

- Great Spangled Fritillary

- Meadow Fritillary

- Pearl Crescent

- Red Admiral

- Common Buckeye

- Hackberry Emperor

- Tawny Emperor

- Northern Pearly Eye

Forest/Field Intergrade:

- Monarch

- Common Wood Nymph

- Red-Banded Hairstreak

Bird Garden

In earlier sections of this chapter we describe the importance of enhancing layers of vegetative structure within the landscape to support a biodiverse assemblage of plant and animal communities, and here we revisit that theme again in the context of providing good habitat for birds. The most effective way to design a garden space that will become a home for many bird species is to grow lush shrub borders and hedgerows replete with fruits and seeds; to plant trees for an overhead canopy; and to fill the landscape between those two layers with pollinator habitat that will attract the insects and spiders that birds feed on for protein. These vegetative elements—the herbaceous flowering layer, the shrub layer and the canopy layer—along with other structural elements like brush piles, nest boxes and water features, will ensure an abundance of bird species throughout the seasons.

Birds need plenty of space to establish a territory, engage in courtship, build a nest, raise and feed their young, and move about in the landscape to find food and cover. The choice of shrub species and how they’re arranged in relation to the surrounding trees and other elements will provide varying degrees of food and cover depending on the time of year. During the growing season in spring and summer, deciduous plants are full of leaves that provide shade and protection, but in winter, birds will need the cover of evergreens such as eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), bayberry (Morella pennsylvanica), American holly (Ilex opaca), and Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana).

In spring, the new growth on trees like oaks, cherry, and poplar are a magnet for insects, and migratory neotropical birds such as orioles, warblers, tanagers, and vireos will utilize the canopy to glean insects from the leaves and branches. As late spring gives way to summer and birds begin breeding, they turn their attention to berry-producing shrubs and other mast (fruits and seeds), as more food becomes available.

Birds will also use hedgerows as a protective corridor to get from one area to another throughout the year. Shrubby thickets made up of species such as blackberries (Rubus), sumac (Rhus), chokeberry (Aronia), dogwood (Cornus) and viburnums (Viburnum) provide excellent cover and mast for catbirds, mockingbirds, thrashers, robins and many others.

The advancing progression of fruit ripening over the seasons ensures there’s always plenty of food available from spring to fall, and many berries and seeds are persistent through the winter. Therefore, prune trees and shrubs in late winter, after the majority of fruits and seeds have been eaten, and before nesting season begins.

In large landscape settings, a good size shrub bed is a large circle of 15 to 30 feet in diameter, with a variety of species planted at least eight feet apart. This many plants results in a deep mass of leaves and branches, where birds can nest or easily dart in and out of when threatened. Alternatively, select one species to fill an entire plant bed, for example five inkberry (Ilex glabra) in one bed, or five American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), or five New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus). In smaller landscapes with less room, plant clusters of just three shrubs instead. Mainly the goal is to group plants together as much as possible, rather than singly, here and there.

Every once in a while we hear folks complain that “all the quail and rabbits are gone,” and they claim it’s because “there’s too many hawks.” But the reality is that the decline of small mammals and birds is because too many landowners—in cities and in rural areas—are “cleaning out” fencerows, hedgerows, and ditches. There’s a definite need to educate the public about the value in letting hedgerows and fencerows stay a little more wild with blackberries, greenbrier, grape vine, and Virginia creeper, in order to preserve habitat for the small mammals and birds that the hawks feed on, whether one lives on a tiny urban lot or on a large rural farm. “Gardening for birds” is so rewarding that it shouldn’t be limited to foundation plantings but extended throughout the landscape.

One other special consideration is the ruby-throated hummingbird, which is a joy to see in any habitat setting, and a bird garden would seem incomplete without these jewels on the wing. As pollinators, they’re especially keen on the nectar of tubular-shaped flowers, but they will also use a few other flower types selectively. If the landscape doesn’t already include a pollinator patch with some of the following plant species in it, choose at least a few from the plant list below, based on the region of the state it’s in, and the growing conditions of the site:

Plant list for ruby-throated hummingbird:

- Wild Columbine (Aquilegia Canadensis)

- Oxeye Sunflower (Heliopsis helianthoides)

- Coral Bells (Heuchera americana)

- Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis or I. biflora)

- Seashore Mallow (Kosteletzkya virginica)

- Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

- Great Blue Lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica)

- Virginia Bluebells (Mertensia virginica)

- Horsemint or Wild Bergamot (Monarda bradburiana or M. fistulosa)

- Beebalm (Monarda didyma)

- Sundrops (Oenothera perennis)

- Narrow-Leaved Sundrops (Oenothera fruticosa)

- Foxglove Beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis)

- Lyre-Leaf Sage (Salvia lyrata)

- Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)—SHRUB

- Yellow Poplar or Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera)—TREE

- Trumpetvine or Trumpet Creeper (Campsis radicans)—VINE

- Crossvine (Bignonia capreolata)—VINE

- Trumpet or Coral Honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)—VINE

- Carolina jasmine or jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens)—VINE

Water Garden for Frogs, Salamanders and Other Aquatic Species

The most effective habitat for supporting frogs, salamanders and other aquatic species is an in-ground wildlife pool that mimics a natural pond or wetland system. There are many options for providing ground-level water features, ranging from small and inexpensive to large and elaborate. Pre-fabricated liners are available at many garden centers and offer a convenient way to get a water source into the landscape quickly. These are often shaped like bathtubs and are available in different dimensions. Most are about three feet deep and made of thick, durable plastic or fiberglass, with built-in, shallow shelves for placement of potted aquatic plants. To install a pre-fabricated liner, dig a proportionate hole to accommodate its shape and size, and make sure the liner is level once it’s in the ground. Remember to call Miss Utility before digging.

Alternatively, one can dig a water garden by hand and create a custom-made shape that’s tailored to the specific site, as big or as small as practical. Locate the garden where it can be seen from a porch or window, and in a level area where there will be at least three to five hours of sunlight per day, with plants shading the water the rest of the day, because most aquatic organisms such as tadpoles need shade protection from temperature extremes.

Dig the deepest area 36 inches, then create shallower edges in concentric circles around this, to make ledges of different heights, such as 24 inches deep, 14 inches deep, and eight or 10 inches deep. The biggest challenge will be to level the sides with each other. Remove any rocks, roots, sticks or other sharp objects from the hole as it’s being dug.

A hand-dug water garden will require two flexible plastic (PVC) liners and two geotextile pads that are at least eight ounces in weight each. The size of the liners and pads should be larger than the total size of the pond (for example, a 30 foot diameter pond would need liners 40 x 40 feet). An ideal size is about 18-20 feet long by 12-15 feet wide, but do some research first to see what size pond liners are actually available on the market. Be sure to buy a liner specifically designed for aquatic gardens, and at least 30-45 mil thick, rather than an ordinary tarp or liner from a hardware store, because the typical home improvement products are usually too thin, and are often pre-treated with a fungicide or algicide.

The installation is assembled like a giant sandwich: start with a two-inch layer of sand on the bottom, or use one geo-textile pad; next lay one of the PVC liners over the sand or pad; then lay another geo-textile pad down; and finish with the second PVC liner. The padded underlayment will help protect the water feature from tree roots and small burrowing animals that might tunnel underneath; some folks use old carpeting for this purpose.

Once the plastic layers are installed, use large rocks to hold the liner down in the middle, as well as along the ledges and around the upper edge. Small logs can also be used for edging around the top. If the pond is large, provide shallow, muddy areas, and also flat rocks in the open, where amphibians can bask in the sun. Fill the pond with non-chlorinated water (or wait several days for the chlorine in treated water to dissipate), and check the level during the driest part of the summer, to see if water may need to be added from time to time. To prevent a terrestrial animal like a bird or a chipmunk from falling in and not being able to escape, place a small branch or log in the pond that an animal can use to climb out.

After all the rocks are in place, the next step is to choose the plants. Just as we use layers of plants in a terrestrial habitat for wildlife diversity, use layers in the water garden to achieve the same effect. Ideally the pond will have enough plants to cover from one half to two-thirds of the surface area of the water. Select native aquatic plants suited to the different levels within the pond. Emergent plants root in the bottom, and their stems and leaves grow upright, out of the water. This is the area where salamanders and frogs spawn and lay their eggs. The matrix of plant roots and stems will provide a good micro-habitat for breeding, as well as multiple places for tadpoles and other organisms to feed and to hide. Floating plants root in the bottom, and their leaves float on the water’s surface. Submergent plants grow completely underwater.

To achieve the best plant diversity, bring a list with you to the aquatic garden center to make the selection (see chart at the end of this section, “Native Plants for Moist Sites or Aquatic Habitats”). Choose plants that are adapted for each of the pond layers (emergent, floating and submergent), as well as plants to place around the edge that will hang over the water and provide additional cover. Avoid using cattails from a local farm pond, because cattails are very aggressive and will fill a pond quickly and choke out other vegetation.

One other consideration is whether or not to consider a recirculating pump or an aerator. The benefits of an aerator are that it provides water movement, keeps the water’s oxygen content high, and minimizes algae build-up. Some amphibians prefer to live and breed in quiet water, while others only live and breed in moving water.

Therefore, if the pond is large enough and designed with different shelves for layers of varying depths, you can provide both types of micro-habitats (i.e., shallow, quiet water, and deeper water with a current) to support a broader range of species. If a pump or aerator will be used, have an electrician install a GFCI (ground-fault protected) outlet in the vicinity of the pond, during the digging stages.

However, if the pond is very small (less than 10 feet in diameter) and is filled with plants, the species that use the water garden will most likely be those that primarily associate with vernal or temporary pools. In this case, the abundance of diverse plants should support enough insect diversity to ensure there will be numerous predaceous insects as well as frogs eating any mosquito larvae, and a pump may not be necessary.

“Mosquito dunks” are not generally recommended for use in a frog pond. These pellets contain spores of bacteria known as Bti, a subspecies of the familiar Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) that is widely used to control grasshoppers, caterpillars and other insects. Bti targets larvae within the suborder Nematocera, which includes mosquitoes; however, there may be larger, ecosystem effects to using Bti in ponds intended for wildlife (Brühl et. al., 2020). As the water garden becomes established with a full complement of diverse plants, many predatory, carnivorous aquatic invertebrates will move into the habitat, such as copepods, water bugs, diving beetles, and dragonfly and damselfly nymphs. These insects and their larvae all feed on mosquito larvae, as do frogs and salamanders.

Perhaps the most important recommendation for providing a safe haven for frogs and salamanders is: do NOT add fish. Fish prey on tadpoles; fish body wastes increase nitrogen in the water and can cause a nutrient imbalance; and goldfish and koi are non-native. Likewise, it is not recommended to purchase tadpoles or snails, as their genetic source cannot be fully confirmed, and releasing organisms from other areas into a new site can introduce pathogens to the environment that may be detrimental to the health of local aquatic populations.

A healthy aquatic habitat will gradually reach an equilibrium as various organisms become established. Over time, though, the pond is bound to gradually fill in with sediment from fallen leaves, and the amount of total water will gradually decrease as the plants’ roots fill in and take over. Therefore, every two to three years in late winter (late February), remove any excessive amounts of decaying material or sediment, being careful to scoop out any newts, salamanders or frogs among the material, and temporarily hold them in a bucket, until the job is completed and they can be returned to the water.

Table 18-5: Native Plants for Moist Sites or Aquatic Habitats

Trees should be planted near a water feature or in a buffer along the edge of a creek. Ferns and grasses should be planted next to a water feature. Herbaceous flowering plants should be planted next to a water feature up to the water's edge. Sedges should be planted at the water's edge or in the water up to 1 foot deep. Emergent flowering plants grow in 1-2 feet of water. Floating plants grow in 2-8 feet of water. Click "next" to see more table rows

| Plant Type | Common Name | Scientific Name | Approx. Height of Plant (ft) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tree | Green Ash | Fraxinus pennsylvanica | 50 |

| Tree | Sweetbay Magnolia | Magnolia virginiana | 20-60 |

| Tree | River Birch | Betula nigra | 45 |

| Tree | Northern Red Oak | Quercus rubra | 100 |

| Tree | Red Mulberry | Morus rubra | 35 |

| Tree | Black Willow | Salix nigra | 40 |

| Small Tree/Shrub | Red Buckeye | Aesculus pavia | 20 |

| Small Tree/Shrub | American Elderberry | Sambucus canadensis | 10 |

| Small Tree/Shrub | American Beautyberry | Callicarpa americana | 10 |

| Small Tree/Shrub | Southern Bayberry | Myrica cerifera | 8-20 |

| Shrub | Highbush Blueberry | Vaccinium corymbosum | 10 |

| Shrub | Possumhaw | Viburnum nudum | 10 |

| Shrub | Red Osier Dogwood | Cornus sericea | 10 |

| Shrub | Sweetshrub | Calycanthus floridus | 10 |

| Shrub | Buttonbush | Cephalanthus occidentalis | 10 |

| Shrub | Silky Dogwood | Cornus amomum | 7 |

| Shrub | Virginia Sweetspire | Itea virginica | 3-6 |

| Shrub | Inkberry | vIlex glabra | |

| Fern | Chain Fern | Woodwardia areolata | 2 |

| Fern | Lady Fern | Athyrium filix-femina | 2-3 |

| Fern | Maidenhair Fern | Adiantum pedatum | 1-2 |

| Fern | Cinnamon Fern | Osmunda cinnamomea | 3 |

| Fern | Royal Fern | Osmunda regalis | 3-5 |

| Fern | Sensitive Fern | Onoclea sensibilis | 1-2 |

| Grass | Inland/River Sea Oats | Chasmanthium latifolium | 2-4 |

| Grass | Eastern Gammagrass | Tripsacum dactyloides | 4-6 |

| Grass | Bushy Bluestem | Andropogon glomeratus | 3-5 |

| Grass | Switchgrass | Panicum virgatum | 4-6 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Cardinal Flower | Lobelia cardinalis | 3-5 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Swamp Milkweed | Asclepias incarnata | 5-6 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | New York Ironweed | Vernonia noveboracensis | 4-6 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Blue Vervain | Verbena hastata | 4-6 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Joe Pyeweed | Eupatorium purpureum | 4-6 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Common Boneset | Eupatorium perfoliatum | 3-4 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Blue Mistflower | Eupatorium coelestinum | 3 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Blazing Star | Liatris spicata | 4 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Turtlehead | Chelone glabra | 2-4 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | New York Aster | Symphotricum novi-belgii | 1-3 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Northern Blue Flag | Iris versicolor | 2-4 |

| Herbaceous Flowering Plant | Southern Blue Flag | Iris virginica | 2-3 |

| Sedge | Tussock Sedge | Carex stricta | 2-4 |

| Sedge | Fox Sedge | Carex vulpinoidea | 3 |

| Sedge | Shallow Sedge | Carex lurida | 3 |

| Emergent Flowering Plants | Arrowhead | Sagittaria lancifolia | 2-3 |

| Emergent Flowering Plants | Pickerelweed | Pontedaria cordata | 2-3 |

| Emergent Flowering Plants | Soft Rush | Juncus effusesv | 3 |

| Floating Plants | American White Waterlily | Nymphaea odorata | NA |

| Floating Plants | Yellow Pond Lily | Nuphar lutea | NA |

| Floating Plants | Illinois Pondweed | Potamogeton illinoensis | NA |

| Floating Plants | Longleaf Pondweed | Potamogeton nodosus | NA |

| Floating Plants | Frogbit | Limnobium spongia | NA |