Chapter 11: Lawns

Chapter Contents:

Grasses that are used for lawns are commonly referred to as turfgrasses. They are durable perennial grasses that can be mowed to a short height to form a uniform, compact, and soft groundcover. They are somewhat tolerant of foot traffic and ideal for sports fields such as golf courses, recreation areas like parks, or residential areas for children’s playgrounds or entertainment.

Producing quality lawns in Virginia can be challenging. Virginia is located within the turfgrass transition zone and its cold winters and hot dry summers are not favorable for establishing or maintaining lawns in an easy, affordable, and environmentally friendly way. However, with proper cultural practices, a healthy lawn can be established and maintained.

Establishing a Lawn

Turf may be established from seed, sprigs, plugs, or sod. The method used depends on the type of grass desired, the environmental and soil conditions, time constraints, and financial considerations. These factors are discussed more in the section on Seed versus Sod. The same basic requirements for lime, fertilizer, and seedbed preparation apply for both seeding and vegetative establishment. After the new lawn is established and growing well, begin a good, comprehensive maintenance program to keep it healthy and attractive.

Soil Test

The first step in establishing a new lawn is to have the soil tested. Test results will determine which basic nutrients are available in the soil, and will allow recommendations to be made for liming and fertilization. Forms and sample boxes, along with instructions for obtaining good samples, are available from your Extension office. Samples should be taken from several areas in the lawn. Samples from areas that have similar soil types should be combined into one sample. For most yards, one combined sample is adequate. Large yards with widely varied conditions may require more samples. There is no need to submit more samples than you are willing to individually treat, if turf areas do not exceed 5 acres.

Pre-Plant Weed Control

Observe the topsoil or lawn area to be planted and determine if there are weeds present that should be controlled prior to planting. Grassy weeds that are particularly troublesome in lawns of Kentucky bluegrass, perennial ryegrass, or fine fescues are dallisgrass, quackgrass, tall fescue, orchardgrass, and bermudagrass. These weeds can be controlled prior to planting by properly applying a non-selective herbicide such as glyphosate.

Controlling troublesome perennial broadleaf weeds prior to establishment can be beneficial. Refer to the most current version of the VCE Pest Management Guide for recommendations on chemical controls and timings specific to individual species.

Pre-plant weed control needs to account for the wait time between when a chemical control is applied and when the area can be seeded to prevent residual herbicide damage to newly planted turf. Refer to product labels for the appropriate wait time.

Pre-Plant Installation of Irrigation and Drainage

If irrigation systems or drainage tiles are necessary, they should be installed prior to topsoil application in order to avoid contamination of topsoil with subsoil. Stockpiling of topsoil is advisable if considerable subsoil grading is necessary.

Soil Preparation

Remove building debris and other trash from the lawn area during all stages of construction. Such material causes mowing hazards and blocks root system development. Rotting wood is often the host for troublesome “fairy ring” diseases which are difficult to control. The subgrade should be sloped away from the house, and the area should be allowed to settle for 2 or 3 weeks before seeding or sodding. Several wetting and drying cycles will aid settling and help you locate low spots in the lawn which should be filled. Topsoil depth after settling should be a minimum of 6 to 8 inches. Therefore, 8 to 10 inches of loose topsoil should be called for in the establishment specifications.

Lime

Soils in most areas of Virginia are acid, and lime recommendations will be made from the soil test to raise the soil pH to 6.5, as based on Virginia Tech Soil Testing Lab recommendations. Lime rates are based on the target pH and the buffer index from the soil analysis. The lime should be tilled into the soil to a minimum depth of 4 to 6 inches. If soil tests indicate low available magnesium levels, dolomitic limestone should be used. Otherwise, use ground agricultural limestone.

Have soil tested

The soil analysis will determine lime and fertilizer needs. The soil should be tested at least a month before the lawn establishment is started.

When to Establish

Seed will germinate only under proper conditions. There are certain periods each year when temperature, moisture, and day length are most favorable for establishing turfgrass. In general, early fall seeding of cool-season grasses is much preferred over spring seeding to allow maximum establishment and growth before the turf’s first full summer. Early spring seedings may also bring good results if moisture is adequate, but it is likely the lawn will need supplemental irrigation to survive the first summer. In Northern Virginia and the areas of Western Virginia at lower elevations, the best seeding dates are mid-to-late March for spring seeding, and the last week of August to mid-September for fall seeding. It may be possible to get good results as late as the middle of October for fall seeding. At higher elevations (greater than 1200 feet) in Western Virginia, the best seeding dates are April and early May in the spring and mid-August to mid-September in the fall. In southern and southeastern Virginia, February 15 to March 30 is the best period to plant for spring warm-season grasses. In the fall, September 15 to October 15 is most suitable for cool-season grasses. Sod of Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue can be installed throughout the year except in mid-winter when the ground is frozen. When extreme heat and drought conditions exist in summer, sodding operations should be delayed. If done under drought conditions, the turf must be kept moist and cool.

Improved strains of warm-season grasses such as zoysiagrass, bermudagrass, centipedegrass, (possible use from Southside through the southern coastal plain of Virginia) and St. Augustinegrass (used on the coast in Southeast Virginia) which are normally sprigged, plugged, or sodded, should be established during May after the soil is warm. There also are improved-quality, cold-tolerant seeded bermudagrasses and zoysiagrasses now commercially available. May and June plantings will have the greatest chance of surviving the first winter, especially for seeded establishments. These grasses have been successfully planted as late as July; however, late summer plantings are not recommended because there is not sufficient time for proper root and rhizome establishment before cold weather.

Seed versus Sod

A quality lawn containing the recommended mixtures of grass varieties and species can be established with either seed or sod (the upper layer of soil with grass growing, often harvested and rolled). Both seed and sod of recommended varieties are available, and the soil preparation for the two methods does not differ. The latest recommendations for top performing turfgrass varieties in Virginia can be found on the Extension publication site.

Initially, seed is less expensive than sod. However, soil erosion potential and heavy weed pressure are both more likely with seeded establishments than with sod. If reseeding of certain areas or even an entire lawn is necessary, the overall expense may be less with sod. Also, because of the time required for seed to germinate and become well-rooted in the soil, there is often excessive potential for erosion. Sodding practically eliminates such problems, a consideration which may be especially important on steep hills or banks

Sodding provides an immediately pleasing turf that is quickly functional and will compete with viable weed seed already present in the soil. When using seed, an intensive weed control program may be necessary to reduce weed competition.

Seed establishment is only recommended in the early fall or early spring, whereas sod may be established in nearly any season if moisture is available.

Seeding and Mulching

A well-prepared seedbed is essential for the establishment of turfgrasses. The seedbed should be tilled to a depth of 6 inches if possible, with lime (if needed), compost and fertilizer worked into the soil prior to seeding. Tilling 1-2 inches of compost into the soil improves soil structure and helps the turf establish more quickly. Prepare a smooth, firm seedbed, then divide the seed and sow in two directions, perpendicular to each other. If low rates of seed are being sown (typical with smaller-seeded grasses like Kentucky bluegrass, bermudagrass, or zoysiagrass), mixing the seed with a dry carrier such as sand, calcined clay, or a granular organic fertilizer will aid in gaining uniform coverage. Cover the seed by raking lightly and rolling. Avoid a completely smooth surface that promotes the washing of the seed. A finished seedbed should have shallow, uniform depressions (rows) about 1/2 inch deep and 1-2 inches apart, such as those made by a corrugated roller. Uniformly mulch the area with straw or other suitable material so that approximately 50% to 75% of the soil surface is covered. This is normally accomplished by spreading 1 bale of straw per 1000 square feet. This amount of mulch would simply be chopped up with the mower the first few times the new lawn is mowed. Heavier rates of mulch that might shade the turf should be removed when the seedlings are about 2 inches tall, being careful not to remove the young, recently rooted seedlings.

Sodding

Soil preparation should be similar to that described for seeding. Take care not to disturb the prepared soil with deep footprints or wheel tracks. These depressions restrict root development and give an uneven appearance to the installed sod. During hot summer days, the soil should be dampened just prior to laying the sod. This avoids placing the turf roots in contact with an excessively dry and hot soil. Premium quality, certified sod is easier to transport and install than inferior grades. Such sod is light, does not tear apart easily, and quickly generates a root system into the prepared soil. Before ordering or obtaining sod, be sure you are prepared to install it. Sod is perishable, and should not remain on the pallet or stack longer than 36 hours. The presence of mildew and distinct yellowing of the leaves is usually evidence of reduced turf vigor.

To reduce the need for short pieces when installing sod, it is generally best to establish a straight line lengthwise through the lawn area. Working from the edge of a sidewalk or driveway is a logical starting point. The sod pieces are then staggered as when laying bricks. A sharpened masonry trowel is very handy for cutting pieces, forcing the sod tight, and leveling small depressions. Immediately after the sod is laid, it should be rolled and kept very moist until it is well-rooted in the soil.

Plugging and Sprigging

The highest quality cultivars of the zoysiagrass, bermudagrass, and St. Augustinegrass must be vegetatively established using either plugs or sprigs. Plugs are small squares/circles of sod grown in a tray. Sprigs are the stems from shredded sod. Sprigs should include leaves, a stolon, and roots.

The soil should be prepared as described for seeding or sodding. Rooted plugs of zoysiagrass are commonly available, and are 1 to 2 inches in diameter with 1 to 2 inches of soil attached. St. Augustinegrass usually requires 4 inch diameter plugs. The plugs should be fitted tightly into pre-cut holes and tamped firmly into place. Plugs are normally planted on 6- to 12-inch centers. Planting plugs on 6-inch centers requires 4000 plugs per 1000 square feet. On 12-inch centers, only 1000 plugs are required per 1000 square feet.

Sprigs can be broadcast over a previously disked area and covered lightly with soil by disking again. They can also be planted in shallow depressed rows on 6 to 12 inch centers, then covered with soil. In either case, the sprig should root at the nodes. Sprigs can be purchased as sod and then shredded, or can often be purchased by the bushel. Generally, one bushel of sprigs is produced from shredding one square yard of sod. Sprigging rates for bermudagrass and zoysiagrass range from 7 to 10 bushels per 1000 square feet.

Post-Planting Irrigation

New seedings and spriggings require intensive irrigation to ensure successful establishment. Seedings require light and frequent watering to ensure that the seed and surface of the soil are constantly moist. Plan to keep the soil moist for 30 days following planting. During hot days this may necessitate 3 or 4 light waterings during the day to provide adequate moisture for rapid and successful germination. If the soil dries out during the germination or sprigging process, the plant material is likely to die. Areas sodded and plugged also require intensive irrigation initially. However, frequent light watering is only required until the sod or plug is rooted. Once sod or plugs are rooted, irrigation applied every second or third day, wetting the soil to a 6-inch depth, is adequate. As a rule of thumb, once the lawn requires mowing, it is time to change the irrigation strategy to a ‘deep and infrequent’ approach.

Renovating an Old Lawn

A lawn of less than satisfactory appearance but fair condition may be renovated without having to be completely tilled. Advantages of renovation include less expense and mess, since minimum tilling of the soil is required. The lawn will be able to take light traffic during the renovation period. Some conditions reduce the chances of successful renovation. If the soil is extremely compacted, has a pH below 5.2, very low soil phosphorus availability, or the grade is very uneven, complete re-establishment with plowing or disking may be a better choice.

Determine Cause of Poor Quality

Lawns usually require renovation because of one or more of the following reasons: poor soil chemical and/or physical properties, poor fertilization practices, inadequate drainage, excessive traffic, poor selection of grass variety or species, weed invasion, compaction, drought, insect or disease damage, or excessive shade.

Have Soil Tested

The soil analysis will determine lime and fertilizer needs. The soil should be tested at least a month before the lawn renovation is started. Simply put – don’t guess, soil test!

Control Weeds and Undesirable Grasses

If possible, control perennial grass weeds such as tall fescue (in warm-season turf), bermudagrass (in zoysia and cool-season turf), nimblewill, and quackgrass prior to the soil preparation process. Glyphosate, applied in accordance with label directions, will control most perennial grassy weeds. Begin treatment with glyphosate 30 to 45 days prior to renovation to provide the opportunity for re-treatment if regrowth occurs. Perennial broadleaf weeds can be controlled either prior to renovation or after the new seed has been mowed two times. If controlling broadleaf weeds prior to renovation, pay attention to any planting restrictions that might be indicated on the label. In most situations, apply the broadleaf weed control at least 30 days prior to soil disruption and seeding.

One very important weed competitor that is a serious problem with spring plantings is crabgrass. Standard preemergent (PRE) herbicides for crabgrass control will also control any grasses that are planted from seed, so there must be a very well defined plan of when grasses will be planted and how one is going to manage the weeds. The VCE Pest Management Guide should always be the resource to consult for the latest information on these pesticides. Two very popular herbicides that fit crabgrass control programs for most (not all) grass establishments from seed are mesotrione and quinclorac. Consult the PMG for the rates and timing of their applications in order to optimize grass establishment and crabgrass control.

Dethatch and/or Aerify if Necessary

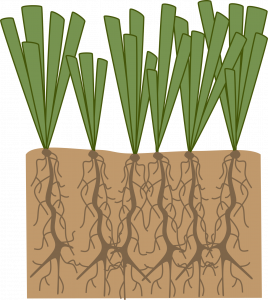

Thatch is an organic mat of stems that forms between the mineral soil and the turfgrass canopy. It is primarily comprised of rhizomes (below-ground stems), stolons (above-ground stems), or seedheads. Grasses that don’t spread by lateral stems typically do not produce a lot of thatch. Due to the high cellulose content of grass, thatch is slow to decay and forms a hydrophobic mat between the soil and grass leaves. Thatch layers greater than ½ inch in thickness will eventually cause a decline in turfgrass performance and will make renovations using seed very difficult..Use a vertical mower or dethatching machine(many rental businesses will have these machines available) to remove thatch (if it is a problem). Even if the existing lawn is not thatch, these machines are great renovation tools because they promote good seed to soil contact.. Seed planted on top of the thatch layer is largely wasted since thatch is a hydrophobic layer of undecomposed organic matter that is not conducive to root establishment.. Aerification with a coring aerifier (often called a ‘plugger’) helps prepare a lawn for renovation by inoculating the thatch with soil, reducing compaction, and creating moisture collecting holes in the soil. Dethatching after aerification helps bust the cores and provide a better seedbed by promoting more soil to seed contact.

Apply Lime and Fertilizer

Consult soil test recommendations.

Sow the Seed

Renovated lawns can be drill-seeded and/or broadcast-seeded. Drill seeding provides the best seed-soil contact and the highest germination rate. Drill seeding alone generally leaves a “row effect,” which can be masked by also broadcast seeding. The best method involves drill seeding in two perpendicular directions and then broadcast seeding. Lightly rake or drag the area after seeding.

Water Frequently

Water lightly and frequently every day until the seed has germinated and developed a 2- to 4-inch root system. Then water less frequently but more deeply to keep the soil moist.

New Lawn Maintenance

Begin mowing the new lawn when the 1/3rd rule applies. This mowing rule of thumb says to never remove more than 1/3rd of the leaf blade during any mowing event. For instance, if the desired maintenance cutting height of a new tall fescue stand is 2 inches, cut the grass when it reaches 3 inches tall. Be sure that the lawn mower blade is sharp. A dull mower tends to pull grass seedlings out of the ground. Try to minimize traffic on the new lawn until it is mature. Broadleaf weed control may be necessary. Do not apply broadleaf weed control to new lawns until they have been mowed three or more times (often indicated on the herbicide label). Begin a good, comprehensive fertilization program based on the recommendations in Extension publications.

Healthy Virginia Lawns: Grassroots in Chesterfield

By Seth Guy, Environmental Educator, Virginia Cooperative Extension, Chesterfield

You can help improve Virginia’s waterways starting in your own backyard! Growing turf in Central Virginia can prove difficult as we live in what is considered a transition zone for turfgrasses. This means that the climate can be hostile towards both cool-season grasses and warm-season grasses. This can lead to the excess use of fertilizers trying to maintain a beautiful lawn. Using excess fertilizers not only becomes expensive, it can also be detrimental to our waterways.

Chesterfield Extension Master Gardeners’ Grass Roots, a Virginia Healthy Lawns program, is an excellent source of assistance for Chesterfield homeowners to determine just what their lawn needs to be as healthy as possible. Master Gardeners support the program, providing information about soil acidity, why the pH matters, when to fertilize your grass and how to minimize a property’s impact on Swift Creek Reservoir and James River, which helps to continue the improvement of the Chesapeake Bay watershed. It all starts with a soil test, a measurement of the customer’s lawn area, and a survey of the condition of the grass and the presence of weeds. For a small fee, a Master Gardener team will perform these tasks and send a soil sample from your lawn to Waypoint Analytical’ s soil lab for analysis to determine the best course of action.

Over the past 16 years since the start of Grass Roots, Chesterfield Master Gardeners have helped more than 6,000 residents adopt the lawn care practices of Virginia Healthy Lawns. This has resulted in beautiful healthy turf for the customers and a reduction of excess nutrients reaching the local watersheds.

Recommended Turfgrass Varieties for Virginia

The Maryland – Virginia Turfgrass Variety Recommendation Work Group meets each spring to consider the previous year’s data from the Virginia and Maryland National Turfgrass Evaluation Program trials and to formulate these recommendations. To qualify for this recommended list, turfgrass varieties: 1) must be available as certified seed, or in the case of vegetative varieties, as certified sprigs or sod; 2) must be tested at sites in both Virginia and Maryland; and 3) must perform well, relative to other varieties, for a minimum of two years to make the list as a “promising” variety and for three years to make the recommended category. All test locations in Virginia and Maryland are considered in making these recommendations.

The Virginia Crop Improvement Association (VCIA) will accept the turfgrass mixtures listed in the current “Virginia Turfgrass Variety Recommendations” publication, which can be found by searching “Turfgrass Variety Recommendations” on the Extension publications website. All seed or vegetative material must be certified and meet minimum quality standards prescribed by the VCIA. Varieties can be considered for removal from these lists due to declining performance or insufficient recent data relative to other varieties. Varieties can also be considered for removal from these lists due to seed availability problems and/or due to seed quality problems. Varieties specific to certain locations in the state due to temperature extremes etc. will also be denoted on the list.

Many seeding specifications (for municipalities, counties, state and governmental agencies, landscape architects, and professional organizations) state that varieties used for turfgrass establishment must come from this list, and that blends or mixtures follow the guidelines for certified sod production. Specifications for state highway seeding are now developed from this list, but their specifications may require some species and/or varieties not normally recommended for uses other than roadside seeding. Seed availability may vary between turf seed suppliers.

Turfgrass varieties fall into two basic categories: cool-season and warm-season. Cool-season grasses, such as Kentucky bluegrass, tall fescue, fine-leaf fescue and perennial ryegrass, have a long growing season in most areas of Virginia and provide green winter color. Warm-season grasses, such as zoysiagrass, bermudagrass, centipedegrass, and St. Augustinegrass go dormant after the first hard frost and stay brown through the winter months. Zoysiagrass greens up around mid-May in northern Virginia. While the winter color of the warm-season grasses may make them less desirable, maintenance costs are somewhat reduced since water requirements are less and the shorter growing season requires fewer mowings per year.

Table 11-1: Temperature ranges (°F)

| Function | Warm-Season Turfgrasses | Cool-Season Turfgrasses |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Shoot Growth | 80-95° | 60-75° |

| Ideal Root Growth | 75-85° | 50-65° |

| Upper Limit Shoot Growth | 120° | 90° |

| Upper Limit Root Growth | 110° | 77° |

| Lower Limit Shoot Growth | 65° | 40° |

| Lower Limit Root Growth | 50° | 33° |

Table 11-2: Turfgrass characteristics

| Type of grass | Leaf Texture | Shade Tolerance | Cold Tolerance | Heat Tolerance | Drought Tolerance | Wear Tolerance | Salinity Tolerance | Fertility Requirements (Nitrogen) | Mowing Height (inches) | Optimum Soil pH Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Bermuda | Medium | Low | Low-High | High | High | Very Good | Good | Medium-High | 1 | 6.0-7.0 |

| Hybrid Bermuda | Fine | Low-Medium | Low-High | High | High | Excellent | Good | Low | 1 | 6.0-7.0 |

| St. Augustine | Coarse | High | Low | High | Medium | Poor | Good | Medium-High | 3 | 6.5-7.5 |

| Fescue | Fine - Coarse | High | High | Medium | Medium | Good | Fine | Medium | 3 | 5.5-6.5 |

| Zoysiagrass | Fine-Medium | Low-Medium | High | High | High | Excellent | Good | Medium | 1 | 6.0-7.0 |

| Centipedegrass | Medium-Coarse | Medium-High | Medium-High | High | Medium | Poor | Poor | Very Low | 2 | 5.0-6.0 |

Table compiled by Randy Jackson, Unit Director. Funding provided by ES-USDA project #91-EWQI-1-9034 Chesapeake Bay Residential Watershed Water Quality Management

The following recommendations are developed from research conducted in Virginia and Maryland. Turf and seed specialists from the University of Maryland, the United States Department of Agriculture, the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, and Virginia Tech concur in making these recommendations.

Kentucky Bluegrass

Best suited to areas in and west of the Blue Ridge Mountains and north of Richmond, Kentucky bluegrass provides lush, blue-green, fine-bladed lawns. It is a fairly aggressive creeper having an extensive rhizome system. This makes it a desirable cool-season grass for heavily trafficked turfs. In the transition zone, bluegrass lawns may require irrigation in the summer to keep from going into summer dormancy. It does not perform well in heavy shade or on poor soil. Kentucky bluegrass is best suited to a well-drained soil and moderate to high levels of sunlight and management. It can be established from seed or sod.

While classified as Kentucky bluegrasses, there are a number of hybrid bluegrasses (crosses between Kentucky bluegrass and Texas bluegrass) now commercially available. These grasses have similar maintenance requirements to standard Kentucky bluegrasses, but appear to be better suited in the warmer climates of Virginia than standard bluegrasses.

Blends of Kentucky bluegrass varieties are recommended in Virginia, as it is thought they are more likely to provide good quality turf over a wide variety of management and environmental situations. There are two categories of blends.

When seeding a mixture of Category I (recommended) seed, individual varieties should make up no less than 10 percent nor more than 35 percent of the total mixture by weight. Category II seed (promising) includes Kentucky bluegrass varieties that can be blended for use in special situations. They can be mixed with Category I varieties at the rate of 10 to 35 percent. Perennial ryegrass is mixed at the rate of 10 to 15 percent by weight with bluegrass in erosion control situations.

Where erosion is a concern or seedings are being made outside of recommended dates, the addition of Virginia Tech recommended, certified perennial ryegrass varieties to the Kentucky bluegrass mixture at 3 pounds per 1000 square feet (10% to 15% on a weight basis) is recommended.

Categories I and II Seeding Rates: 1.5 to 2.5 lbs per 1000 square feet.

Tall Fescue

Tall fescue is a fine to moderate coarse-textured turfgrass which is tolerant of a wide range of soil types and climatic conditions. It provides very good quality turf under low to moderate management levels and can be established from seed or sod.

Tall fescue does not have the recuperative potential of Kentucky bluegrass since it does not spread by rhizomes (rhizomatous tall fescues are in their early stages of development, but lateral growth rates are still not comparable to those of bluegrass at this time). Therefore, infrequent overseeding may be necessary to maintain desirable turf density in tall fescue lawns.

The fine-bladed turf-type tall fescues dominate the home lawn market in this area. The leaf texture is now so fine that they are commonly mixed with Kentucky bluegrass in sod production. A 90% tall fescue/10% Kentucky bluegrass mixture, whether planted as seed or sod, provides increased recuperative potential and may be advantageous where traffic is expected.

Seeding rate: 4 to 6 pounds per 1000 square feet of tall fescue blends, 3-4 pounds per 1000 square feet for standard mixtures (90-95% tall fescue plus 5-10% Kentucky bluegrass).

Creeping Red, Hard, and Chewing Fescues

These grasses are known collectively as the fine-leaf fescues. As a group of grasses, they exhibit the best tolerance of shade, drought, low-nitrogen, and acid soil. These cool-season grasses require the least intensive maintenance of any of the grasses adapted to Virginia. They perform best in shady lawns in mixtures with shade-tolerant Kentucky bluegrasses as noted earlier. They are excellent choices for reduced input turfgrass areas such as highway rights of way, cemeteries, etc. They have very poor tolerance of intensive traffic or poorly drained soils. Choices in seed are quite limited for all species of fine-leaf fescues. Seed is more limited for fine fescues than any other turfgrass in this area, but for the first time, there is now fine-fescue sod available from a limited number of growers in the state. Seeding Rate: 3 to 5 lbs. per 1000 square feet.

Perennial Ryegrasses

Perennial ryegrass is a fine-medium textured grass that mixes well with Kentucky bluegrass. Some strengths of the perennial ryegrasses are their quick germination and establishment rate, good traffic bearing characteristics as a mature turf, and early spring green-up. They blend well with Kentucky bluegrasses to provide quick erosion control. However, they tend to be susceptible to disease in hot weather and exhibit poor heat and drought tolerance. At present in Virginia, monostands of perennial ryegrass are not capable of providing the level of season-long quality normally associated with a good Kentucky bluegrass mixture without fungicide support. They are best utilized in mixtures with Kentucky bluegrass (5-10% by weight), as noted earlier. Perennial ryegrass is only currently recommended in monostands on heavy traffic areas such as athletic fields where the benefits of rapid germination from seed and traffic tolerance as a mature turf are valued. Variety recommendations are listed with the Kentucky bluegrass recommendations. For standard seedings of perennial ryegrass, use 3-5 pounds per 1000 square feet. Perennial ryegrass also has one additional use for lawns and that is as a winter overseeding component, primarily on bermudagrass lawns. The ryegrass is introduced to the lawn in the early fall for winter color and growth. Typical winter overseeding levels are 5-10 lbs per 1000 square feet for lawns. Remember that the ryegrass will be a competitor with the bermudagrass next spring and will cause a delay in spring greening of the bermudagrass. It is not recommended to overseed any of the other warm-season grasses.

Zoysiagrass

Zoysiagrass is a warm-season grass of fine to medium texture that turns brown with the first hard frost in the fall and greens up about mid-May. Zoysiagrass as a whole has the best cold tolerance of the warm-season grasses used in Virginia, particularly the wider-leaf varieties that are Z. japonica species. Finer textured zoysias of the Z. matrella species are now used throughout Virginia, but they are not generally considered to be as cold hardy as the Z. japonica varieties. It spreads by both rhizomes and stolons, but is a very slow creeper. It is well-suited for lawn use in Virginia and has a low fertility and irrigation requirement. It does well in full sun and has moderate shade tolerance. Its density as a mature turf precludes much weed control and when managed properly, it has very few disease and insect problems as well. The grass has a slow recuperative potential and, therefore, is not recommended for heavily trafficked lawns or athletic fields. It can be established from sod, plugs, or sprigs and with recent developments, a few improved varieties can be established from seed. However, its rate of establishment is extremely slow regardless of the establishment method. Zoysia plugs planted on 12-inch centers will normally require two or three growing seasons to provide full cover. If established from seed, 2-3 lbs of pure live seed per 1000 square feet are recommended, anticipating it will take a full growing season to gain coverage from a mid-spring/early summer planting.

Planting Rate: 2-inch diameter plugs on 6- to 12- inch centers or sprigs broadcast at 7 to 10 bushels per 1000 square feet will require 2 to 3 growing seasons for 100% cover. Planting Dates: May 1 to July 15.

Bermudagrass

Bermudagrass is a fine-bladed, warm-season grass that aggressively creeps by both rhizomes and stolons. Bermudagrass has exceptional drought tolerance and its aggressive growth habit and tolerance to mowing heights of as low as ½ inch make it a great grass for athletic fields and golf course fairways. Its use as a lawn is best suited to the warmest areas of Virginia, but recent releases in cold-hardy varieties (both seeded and vegetative) have expanded the possibility of it being used anywhere in the state. Hybrid bermudagrass can be established by sod, sprigs, or plugs. Two-inch diameter plugs of bermudagrass planted on 12-inch centers will normally provide 95% to 100% cover in one growing season. Seeded bermudagrasses are established at 0.5 to 1 pound of pure live seed per 1000 square feet. Sprigging Rate: 7 to 10 bushels per 1000 square feet. Moderate winter damage can be expected on bermudagrasses once every 6 or 7 years in Virginia.

Centipedegrass

Centipedegrass is a coarse-textured stoloniferous warm-season grass that is adapted in southern Virginia from Martinsville to the coast. It is the lowest maintenance, highest density warm-season grass available. Centipedegrass is established primarily from seed, but sod is available (most coming from farms in the Carolinas). It has a characteristic yellow-green color and prefers acidic soil conditions. Its shade tolerance is moderate and it has very poor traffic tolerance. It is an excellent low-input turf for the warmest climates of Virginia. Centipedegrass is established at levels of ¼ to ½ pound of pure live seed per 1000 square feet.

St. Augustinegrass

St. Augustinegrass is a coarse-textured stoloniferous warm-season grass that has the best shade tolerance of this category. It is grown almost exclusively on the coast of Virginia where the climate is moderated by the ocean and does not persist in any area that has extreme winters. St. Augustinegrass is a very aggressive creeper that has the highest pest pressure (insect and disease) of any of the warm-season grasses. Its use in far southeastern Virginia will primarily focus on shaded lawns and general purpose turfs. St. Augustinegrass can be established by plugs or by sod.

Grass Choices for Virginia Beach

The eastern part of Virginia (zones 7b to 8a) is best suited for warm-season grasses though the predominant lawn grass continues to be the cool-season tall fescue.

Warm-season grasses have the potential for winterkill during extreme winters, they will be dormant (i.e. no green color) 4-5 months out of the year, some are serious weed problems (bermudagrass, aka wiregrass), and not all varieties can be established from seed. However, warm-season grasses typically require 30% less water and have much lower pest pressures than cool-season turfgrasses, so an argument can be made that warm-season lawns can actually be quite ‘enviromentally friendly’ when properly selected and maintained.

Warm-season grass choices for Virginia Beach include: Bermudagrass, Centipedegrass, St. Augustine, Zoysiagrass. A cool-season option is tall fescue.

Purchasing Quality Seed

The purchase of lawn seed is a long-term investment, as the seed you buy will influence your success in developing a beautiful lawn. It is not possible to evaluate the quality of seed by looking at it. Information that will help you make a wise choice is printed on the seed packages.

There are differences in lawn seed, and it pays to compare. The price you pay for seed will represent only a small portion of the total cost of planting, fertilizing, mowing, etc. Don’t let low cost be the only factor you consider when purchasing lawn seed. Choose those varieties that have been tested and proven to be the best for your area of Virginia.

Virginia has a seed label law that is basically a truth-in-labeling law. The label on the package must include an analysis of the seed it contains. This analysis enables the purchaser to determine the kind of seed contained in the package, estimate how well it should perform, and compare its cost-effectiveness with other brands.

Example Seed Label:

Kind: Kentucky bluegrass

Variety: Super-Duper

Pure Seed: 98%

Germination: 85%

Inert Matter: 1%

Date of Test: (month and year)

Other Crop Seed: 0.7%

Lot# – 1A

Weed Seed: 0.3%

Noxious Weeds: 120 Annual Bluegrass per pound

John Doe Seed Co., Richmond, VA

- Germination – The percentage of viable (live) seed. The date of test should be within the last 12 months.

- Pure Seed – The percentage (by weight) that is actually seed of the crop specified.

- Inert Matter – The percentage (by weight) of chaff, dirt, trash, and anything that is not seed.

- Weed Seeds – The percentage (by weight) of all weed seeds in the sample and the number of noxious weed seeds present. If possible, avoid seed lots with noxious weeds.

- Other Crop Seeds – The percentage (by weight) of crop seed other than the crop specified. For example, in tall fescue, this includes orchardgrass and ryegrass. In Kentucky bluegrass, it can include bentgrass, ryegrass, tall fescue, or perennial ryegrass contaminants.

Cost Effectiveness

When considering seed lots of similar quality, compare the amount of pure live seed (PLS) in the package. The only thing you really want to pay for is seed that will grow. To determine the amount of PLS, look at the analysis on the label, multiply the germination percentage by the percentage of pure seed, and then multiply by 100 to get the percentage pure live seed.

Calculating pure living seed example

To obtain the cost per pound of PLS, divide the price per pound by the PLS. If the seed costs $2.25 per lb, then 2.25 ÷ 0.833 = $2.70, the actual cost per pound of pure live seed.

Similarly, when it comes to planting rates, use the PLS value. If the recommendation is to plant 2 lbs of pure live seed per 1000 square feet, and the PLS is 83.3, then one needs 2 ÷ 0.833 = 2.4 lbs of seed from the package per 1000 square foot.

Quality

Certified seed is a guarantee from the seller that you will get the kind and variety of lawn seed named on the label. Buying certified seed is a good practice. If the seed is certified, a blue certification label will be attached to the seed package.

The Virginia and Maryland Cooperative Extension Services have worked with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, seed nurseries, and the Virginia Crop Improvement Association to develop a program that helps purchasers recognize quality lawn seed. In both states, special labels are placed on packages containing seed that meets very high standards of purity, germination, and freedom from weed and other crop seed. Seed in a package that carries one of these labels is certified and recommended for use in both states.

Purchasing Quality Sod

There are several types of sod being grown in Virginia. The basic types are Kentucky bluegrass blends, tall fescue-Kentucky bluegrass mixtures, bermudagrass, and zoysiagrass. Each of these types of sod is best suited to particular uses and geographic areas of Virginia. Some sod producers grow sod in the Virginia Crop Improvement Association (VCIA) certified sod program, which means that the sod produced must meet established standards of quality.

VCIA-certified sod is high-quality and meets rigid standards which require preplanting field inspections, prescribed varieties and mixtures, periodic production inspections, and a final preharvest inspection. This program provides the consumer with guaranteed standards of quality. Sod in the VCIA program which cannot quite meet program VCIA-certified standards may be classified as VCIA approved sod and sold at a lower price than sod in the certified category which meets all VCIA standards. VCIA-certified sod can be identified by its label. High quality sod is also available outside the VCIA certified sod program, but it is not graded by standards and quality and can only be ensured by pre purchase inspection. The following four products comprise 98% of Virginia’s sod market: Kentucky bluegrass blends, Tall fescue or tall fescue-Kentucky bluegrass mixtures, Bermudagrass, Zoysiagrass.

Annual Lawn Maintenance

The wide variety of microclimates and soil types make it difficult to formulate a uniform program for lawn maintenance in Virginia. The basic factors required for maintaining a lawn are discussed; however, the recommendations may need to be modified for your particular location. As mentioned earlier, the first thing to do is have the soil tested.

In addition to considering the genetic potential of the turfgrass in your lawn, important factors in maintaining high turfgrass quality include an annual program of mowing, fertilization, weed control, irrigation, and leaf management. In addition to these, the following cultural practices may be necessary in some years: dethatching, pH adjustment, aeration, disease control, and insect control. In order for these maintenance practices to be fully effective, their timing is of utmost importance. Please refer to the respective cool-season or warm-season calendar for the optimum timing of main maintenance practices.

Maintenance Calendar for Cool-Season Turfgrasses in Virginia:

- Seeding (initial establishment and renovation): Preferred timing August-October, second best timing March-May

- N Fertilization: Preferred timing August-October, second best timing March-May and November-December

- PRE herbicides: Preferred timing March-April (targeting summer annual weeds) or August-September (targeting annual bluegrass and winter annual broadleaves)

- POST herbicides: Preferred timing March-June or August-November (weeds must be actively growing to achieve control with postemergence herbicides)

- Cultivation/dethatching: Preferred timing September-November, second best timing March-April

Maintenance Calendar for Warm-Season Turfgrasses in Virginia

- Planting (initial establishment and renovation): Preferred timing May-June, second best timing July

- N Fertilization: Preferred timing April-August, second best timing mid-February-mid-March

- PRE herbicides: Preferred timing March-April (targeting summer annual weeds) or August-September (targeting annual bluegrass and winter annual broadleaves)

- POST herbicides: Preferred timing March-October, second best timing December-mid-February (weeds must be actively growing to achieve control with postemergence herbicides)

- Disease concerns: May-July, September-October

- Insect concerns: July-early-August

- Winter overseeding: Preferred timing August-early-October

- Cultivation/dethatching: Preferred timing May-early-June, second best timing late-June

Genetic Potential

The potential for a lawn to provide a quality surface is very dependent upon the varieties of grass in the lawn. New, improved varieties are being released each year. Periodic infusion of improved varieties will increase the chances of producing a high-quality lawn. The best maintenance program is not likely to overcome the limitations of inferior turfgrasses in the stand.

Mowing

Mowing grass is one of the most time-consuming practices in turfgrass management, and yet the total impact of mowing management is seldom considered. To appreciate the true impact of mowing on turfgrass, it is necessary to understand the physical, environmental, and physiological effects of mowing on the turfgrass community.

The most obvious physical effect of mowing is the decrease in leaf surface area of the grass plants. The grass plant’s leaves are the site of photosynthesis, and any decrease in leaf surface area proportionately decreases the plant’s ability to produce the carbohydrates essential for root, shoot, rhizome, and stolon growth. If more than 1/3 of the grass vegetation is removed during mowing, root growth is temporarily slowed by the plant’s inability to produce carbohydrates at the previous rate. Carbohydrates can be pulled out of reserve to enhance extensive root, rhizome, and stolon development. However, carbohydrate reserves can be called upon to these structures only a limited number of times while the grass plant is recuperating from the shock of a severe mowing. We need to think of mowing primarily as a carbohydrate-depleting management factor. Improper mowing habits can weaken the plant as the mowing season progresses, reducing its recuperative potential and predisposing it to insect, disease, and drought susceptibility. It has been shown that severe defoliation of the grass plant has extreme effects upon root growth. For example, in cases where 50% of the existing Kentucky bluegrass foliage was removed by mowing, only 35% of the roots were producing growth 33 days after mowing.

Wound hormones are produced every time grass is cut. These compounds along with phenol oxidase enzymes are involved in wound-healing. The production of compounds involved in healing mowing wounds occurs at the expense of food reserves. If you are cutting grass with a dull mower, you are creating severe wounds that require more wound healing compounds and therefore more use of stored food reserves. Be sure to keep your mower blades sharp! Continuous use of dull mowers depletes the plant of stored reserves necessary for survival during the stress-filled months of July and August. Eventually the plant’s ability to heal the mowing wound is impaired by a lack of food reserves, and the open wound becomes a site of fungal entry leading to serious disease problems. Every unit of plant energy that must be utilized to heal dull mower wounds is simply one less unit that will be available for healing during periods of stress.

Nothing is more mismanaged in lawns than their cutting height. Lowering the mowing height beyond those for which a grass is adapted severely disrupts the environmental and competitive forces that exist in the turfgrass community. In a mixed community of turfgrass plants, some plants will become less competitive as the mowing height is lowered. It is essential to realize that lowering mowing heights to 1 inch or less decreases the amount of leaf area intercepting sunlight. Lower mowing heights increase the number of plants per unit area for some grasses (for instance, some bermudagrass varieties), but it is highly likely that the individual plants in the crowded community become weaker, and for such types of mowing, specialized mowing equipment (i.e. reel mowers) are required. Weaker plants require more intensive management to be able to withstand periods of stress. Suboptimal mowing heights in Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue often lead to increased weed populations of annual bluegrass and crabgrass. The table below shows recommended mowing heights for turfgrasses commonly used. The lowest ranges of these heights should only be used during the most optimal growing periods of the year (e.g. summer for bermudagrass or zoysiagrass, late summer/early fall and early to mid-spring for tall fescue or Kentucky bluegrass). Mowing at these lower ranges during optimal growing periods can actually improve turfgrass density. However, it is very prudent to begin raising the cutting height of a respective grass 4-6 weeks before the onset of a predictable environmental stress period such as summer or winter. As a rule, raise the cutting height of cool-season grasses in mid-May and raise the cutting height of warm-season grasses in early September so that the grasses are better prepared to survive the coming environmental stress period.

Table 11-3: Turfgrass mowing heights for lawns (inches)

Heights of 1 inch or lower are best achieved with a reel mower

| Type of grass | height |

|---|---|

| Kentucky bluegrass | 1.5-2.5 |

| Tall fescue | 3-4 |

| Creeping red fescues | 2-3 |

| Perennial ryegrass | 1.5-2.5 |

| Bermudagrass | 0.5-2 |

| Zoysiagrass | 0.75-2 |

| Centipedegrass | 1-2.5 |

| St. Augustinegrass | 3-4 |

Selecting higher mowing heights for cool-season grasses helps to maximize the amount of food being produced by photosynthesis. Higher mowing heights will reduce stress levels on the turf and, at the same time, increase the likelihood of the grass surviving drought, since root development potential is increased by the higher mowing height.

Frequency of mowing can have severe effects on turfgrass communities. Excessive mowing frequency reduces total shoot yield, rooting, rhizome production, and food reserves. Mowing frequency should be determined by seasonal growth demands, and should be often enough that no more than 1/3 of the existing green foliage is removed by any one mowing.

Collecting clippings on home lawns is not advised. There is no significant benefit to the lawn derived from the collection of clippings if the lawn is being mowed with the proper frequency. Clippings are not a major contributor to thatch buildup. They do provide significant amounts of nutrition to the lawn as they decompose. Three years of returning clippings to a lawn has been shown to increase the growth rate 38% over lawns where clippings were not returned. In addition, earthworm populations increase where clippings are returned, improving aeration and water infiltration.

In summary, mowing is the most frequently necessary maintenance practice in the production of a good lawn. For good results, mow as high as is reasonable for the desired appearance and use of the turf, use a sharp blade, and don’t mow more often than necessary – but do mow often enough so that plant height is being reduced by not more than 1/3 each time. A final thought – keep the clippings on the lawn to utilize this ‘free fertilizer’ and protect water quality that can be endangered from clippings that enter storm water drains.

Fertilization

The time table for fertilizing cool-season grasses is completely different from that of warm-season grasses. Warm-season grasses go dormant during the time when the cool-season grasses make the most effective use of fertilizer for root growth and development.

Late-fall fertilization is essential in the maintenance of quality cool-season grasses. The advantages of late-fall fertilization observed in research and field observation are increased density, increased root growth, decreased spring mowing, improved fall-to-spring color, decreased weed problems, increased drought tolerance, and decreased summer disease activity. The amounts of fertilizer to apply and the time periods when they should be applied are critical.

The ideal lawn fertilization program provides the nutrition that maximizes the chances of producing a quality lawn. Temperature and moisture vary greatly and affect turfgrass growth. Therefore, nutritional needs vary from month to month. Excessive stimulation of growth from nitrogen fertilizers can be more detrimental than no fertilization at all. The source of nitrogen in fertilizers influences nitrogen availability to the turfgrass plant. There are two types of nitrogen sources: quickly available and slowly available. Quickly available materials are water-soluble and can be immediately utilized by the plant. Slowly available nitrogen sources release their nitrogen over extended periods of time and, therefore, can be applied less frequently and at higher rates than the quickly available nitrogen sources.

The numbers on the fertilizer bag (such as 10-10-10 or 46-0-0) indicate the percent of Nitrogen (N), Phosphate (P2O5), and potash (K2O) in the fertilizer. If your soil test indicates low or medium levels of phosphorus or potassium, complete fertilizers (those containing nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium) should be used. If high levels of phosphorous and potassium are present in the soil, then fertilizers supplying only nitrogen will be adequate.

Fertilizers can provide nitrogen to plants immediately or over an extended period of time. The amount that can be safely applied at one time depends upon the availability of the nitrogen. The portion of the nitrogen that is slowly available is listed on the fertilizer bag as Water Insoluble Nitrogen (WIN). For example, a 20-10-10 fertilizer with 5% WIN actually provides 5/20 or 1/4 of its nitrogen in the slowly available form. A 50 lb. bag of this material would provide 10 lbs. of total Nitrogen (.20 X 50 = 10 lbs.) of which 2.5 lbs. (.05 X 50 = 2.5) would be slowly available (WIN).

A fertilizer label will provide the following information

Guaranteed Analysis

- Total Nitrogen 16%

- Water Insoluble Nitrogen (WIN) 5.6%

- Available Phosphoric Acid (P2O5) 4%

- Soluble Potash (K2O) 8%

The above percentages are relative to the total fertilizer by weight. To find the percentage of WIN relative to the total nitrogen, perform the following calculation:

5.6/16 x 100 = 35%

WIN may also be listed in the asterisked fine print of a water soluble source. For Example:

Guaranteed Analysis

- Total Nitrogen 35%

- 35.0% Urea Nitrogen*

- Soluble Potash (K2O) 8%

*Contains 12% Slowly Available Nitrogen from coated Urea

Note: In this case, total nitrogen percentage (35%) is relative to the total fertilizer by weight, and the urea nitrogen percentage (35%) is relative to the total nitrogen. The slowly available nitrogen percentage (12%) is relative to the total fetilizer (35 x 35/100 = 12.25).

Nitrogen Fertilization of Cool-Season Grasses

Table 11-4: Program I

Nitrogen fertilization of cool-season grasses using predominantly quickly-available nitrogen fertilizers (less than 15% slowly-available nitrogen or WIN)

Nitrogen Application by Month (lbs N/1000 sq ft)

| Quality Desired | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | May 15 to June 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Medium | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0 |

| High | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0-0.5 |

Table 11-5: Program II

Nitrogen fertilization of cool-season grasses using predominantly slowly-available fertilizers (15% or more slowly-available nitrogen or WIN)

Nitrogen Application by Month (lbs N/1000 sq ft)

| Quality Desired | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | May 15 to June 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Medium | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0-0.2 | 0 |

| High | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0-0.5 |

Important Comments about Programs I and II:

- Fine fescues perform best at 1-2 lbs of nitrogen per 1000 sq ft per year.

- Applications in successive months should be at least 30 days apart and deliver no more than 0.7 lb of N per 1000 square feet per active growing month.

- Natural organic and activated sewage sludge products should be applied early in the August 15 to September 15 and the October 1 to November 1 application periods to maximize their effect since they release N due to microbial activity.

- Up to 0.7 lb of nitrogen in Program I and up to 0.9 lb of nitrogen in Program II may be applied per 1000 sq ft in the May 15 to June 15 period if nitrogen was not applied the previous fall or to help a new lawn get better established.

Nitrogen Fertilization of Warm-Season Grasses

Table 11-6: Program III

Nitrogen fertilization of warm-season grasses using predominantly quickly-available nitrogen fertilizers (less than 15% slowly-available nitrogen or WIN)

Nitrogen Application by Month (lbs N/1000 sq ft)

| Quality Desired | April | May | June | July/August |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Medium | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| High | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

Table 11-7: Program IV

Nitrogen fertilization of warm-season grasses using predominantly slowly-available nitrogen (15% or more slowly-available nitrogen or WIN)

Nitrogen Application by Month (lbs N/1000 sq ft)

| Quality Desired | April | May | June | July/August |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Medium | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| High | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Important Comments about Programs III and IV:

- If overseeded for winter color, add 1/2 to 1 lb of readily available nitrogen per 1000 sq ft in Sept./Oct. and/or Nov.

- Applications in successive months should be approximately four weeks apart.

- Centipedegrass and mature zoysiagrass perform best at 1 to 2 lbs of nitrogen per 1000 sq ft per year.

- Improved winter hardiness on bermudagrass will result from the application of potassium in late August or September.

If no WIN is listed on the fertilizer label, assume that it is all water-soluble or quickly available nitrogen, unless the fertilizer label indicates that it contains sulfur-coated urea. Sulfur-coated urea fertilizers provide slowly available nitrogen, but the fertilizer label does not list it as WIN. If the fertilizer contains sulfur-coated urea, include that portion as water insoluble nitrogen when determining the portion of the fertilizer that is slowly available.

Statements on a fertilizer bag such as “contains 50% organic fertilizer” do not mean that the fertilizer is 50% slowly available. It is impossible to calculate the amount of WIN from this information. For example, Urea (46-0-0) which contains carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, is in fact an “organic” fertilizer, yet it contains no slow release nitrogen.

Weed Control

Weeds in the landscape are considered as a sub-category of pests. As such, Integrated Pest Management (IPM) applies equally to weeds. For more information on IPM, see Chapter 7 “Integrated Pest Management and Pesticide Safety”

Weed control can be minimized by good mowing and fertilization management, since this makes grass more capable of competing with weeds. If chemical control should be necessary, care should be taken to apply chemicals at the time of year when they will be most effective. Follow label directions closely and never exceed recommended rates. Improper application of weed control chemicals can result in damage to desirable grasses, ornamental plantings, and the environment.

There are two basic groups of weeds: broadleaf weeds and weedy grasses. Broadleaf weeds consist of the familiar dandelions, chickweed, clover, ground ivy, wild onions, oxalis, plantain, and anything which is not classed as a grass. Examples of weedy grasses are nimblewill, quackgrass, crabgrass, and goosegrass. Of course, even what is a desirable turfgrass for some can be a serious weed for others (e.g. bermudagrass in tall fescue, creeping bentgrass in Kentucky bluegrass). Control for each of the two groups varies.

There are good selective herbicides available for broadleaf weed control. In general, broadleaf weeds respond best to weed killers when they are most actively growing and/or in the seedling stage. This is usually in early to mid fall and mid to late spring. When equally effective, fall applications are preferable because fewer ornamental and garden plants are in an active state of growth. Applications of high rates of weed killer during hot, dry conditions may brown desirable grasses. Annual weedy grasses such as crabgrass, foxtail, and goosegrass are controlled with preemergence herbicides that are applied in the spring, prior to germination. Pesticide recommendations for control of specific broadleaf and grassy weeds are contained in the VCE Pest Management Guide.

Control of perennial weedy grass such as common bermudagrass, nimblewill, and quackgrass is more difficult because selective herbicides that have activity generally can not control the weed in single applications. Therefore, persistence in weed treatment is required and in some instances spot spraying, physical removal, or total kill of existing lawns may be necessary. Pesticide options for controlling perennial weedy grass are available in the VCE Pest Management Guide.

Sedges are often called ‘nutgrass’ but they are not in the grass family. They can easily be identified by their triangular stem. Sedges can be controlled with use of herbicides that specifically target sedges. These herbicides do not damage mature turfgrass. Sedges are warm-season in nature and there are both annual and perennial biotypes. They are best controlled soon after their emergence in early-mid summer.

Control of mosses is usually done through cultural means. Improving surface drainage, reducing soil compaction, improving soil fertility and adjusting the pH can improve the ability of turf to outcompete moss. While some selective pruning can increase exposure to sunlight, lack of sunlight is often the main reason for moss to out complete turf in soil that has improved to otherwise favor turf. In this case, alternative ground covers are a better option than turf.

Weed Identification

Virginia Tech’s Weed Identification website is a very comprehensive weed identification tool: Virginia Tech Weed ID website. Additional resources for weed identification include: VCE publication “Identification of Virginia’s Noxious Weeds” SPES-244NP

Virginia Cooperative Extension also offers weed identification services through its Weed ID clinic. For more information on weeds, see the current VCE Pest Management Guide.

Irrigation

Lawns can use an inch or more of water per week in hot, dry weather. If rainfall does not provide this much water and soil moisture reservoirs are depleted, irrigation will be necessary to keep the lawn green. The lawn should be watered when the soil begins to dry out but before the grass actually wilts. At that stage, areas of the lawn will begin to change color, displaying a blue-gray or smoky tinge. Also, loss of resilience can be observed; footprints will make a long-lasting imprint instead of bouncing right back. Alternate wetting and drying periods are normal and beneficial to developing balanced microbial activity in soils. Ideally, the lawn should be watered shortly after the development of the blue-grey cast noted above.

Cool-season grasses usually go semi-dormant in the hottest part of the summer, returning to full vigor in cooler fall weather. If you want to keep the lawn green through the summer, regular deep watering will be necessary. If the lawn does go dormant (turns brown), let it stay that way until it naturally greens up again. Too many fluctuations between dormancy and active growth can weaken the lawn.

Light sprinkling of the surface is actually more harmful than not watering at all, since this encourages root development near the surface and increases crabgrass germination. This limited root system will require more frequent waterings and will necessitate keeping the surface wet, which is ideal for weeds and diseases. Watering should be an “all or nothing” type of commitment. If you water, do it consistently and deeply. If you don’t intend to be consistent, it is better not to water at all and to allow the grass to go dormant until natural conditions bring it back. Encouraging deep root growth by irrigating infrequently, but heavily, will maximize water use efficiency and turfgrass quality.

The best time to water a lawn is in the early morning. Evaporation is minimized and water-use efficiency is better than during midday. Early evening or night watering is not encouraged because it leaves the blades and thatch wet at night. This maximizes the potential for disease activity.

Dethatching

In addition to regular maintenance factors already discussed, in some years it may be necessary to remove thatch from lawns with thatch-forming grasses. Thatch is the tightly interwoven layer of living and dead stems, leaves, and roots that exists between the green blades of grass and the soil surface. This layer of decomposing organic matter accumulates on the soil surface in an innocuous fashion. During the early stages of thatch development, when it measures less than 0.5 inch in thickness, it can actually be beneficial to the grass. Thin layers of thatch can increase wear tolerance of turf by providing better dissipation of compaction forces, reducing weed populations by providing hostile conditions for germination, reducing water evaporation by blocking sunlight and air exchange with the soil surface, and insulating crown tissue, protecting it from frost and traffic damage. Thatch problems are inevitable with certain grasses under intensive turfgrass management programs unless thatch reduction principles are built into the program. The single cause of thatch buildup is the fact that the accumulation rate of dead organic matter and stems on the soil surface is greater than the decomposition rate. There are many reasons for this imbalance between rate of accumulation and decomposition. Some of the factors involved include excessively high nitrogen levels, the type of turfgrass, excessive irrigation, mowing management, chemical use, and soil type.

The effect of excessive thatch buildup upon turfgrass quality is subtle but deadly. This layer of undecomposed organic matter is capable of altering pest populations, moisture relations, nutrient utilization patterns, soil temperatures, and other climatic and biotic factors.

For all intents and purposes, thatch is not caused by leaf clippings. Recycle clippings to the lawn to take advantage of their nutrient composition.

The moist microclimate created by the thatch layer favors fungal invasion and allows pathogenic microorganisms to live and sporulate. The probability of insect pathogens surviving the winter is increased by the insulating effect of thatch. Soil-borne fungus and insect pathogens often escape control methods due to the inability of applied pesticides to penetrate the thatch layer. The thatch layer prevents adequate water infiltration, causing reduced root growth and increased potential for wilt damage. When thatch layers are kept moist, roots tend to develop in this zone, and crown regions of the individual turfgrass plants tend to be elevated in the thatch. This elevation of the crown region away from the soil leads to increased exposure to temperature extremes and a greater probability of stress-related damage. Interception of lime and fertilizer applications by thatch layers produces erratic fertilizer response. In some cases, the microorganisms tie up the applied nitrogen, rendering it unavailable to the turfgrass plants.

Preventive thatch management involves turfgrass selection, modification of nutrition, cultivation, mowing, and irrigation practices. Kentucky bluegrass, creeping red fescue, bermudagrass, zoysiagrass, and St. Augustinegrass are all prone to thatch development under intensive management because they produce lateral stems. Tall fescue and perennial ryegrass, bunch type-grasses, are low thatch producers and if they do produce thatch, then they are being mismanaged in terms of N fertilization.

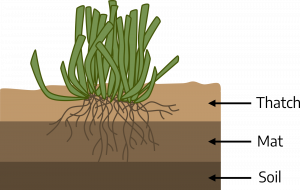

Figure 11-4 shows a block of turf with thatch, mat, and soil layers in profile. Note that the crown of the grass plant is elevated into the thatch layer. The mat is the layer of decomposing thatch which is becoming integrated into the soil. There is no simple method of controlling thatch development. Preventive programs for thatch reduction should be built into the maintenance program. Curative programs involving the labor-intensive process of dethatching may also be required at times.

The pH of the thatch layer appears to be more important to thatch decomposition than soil pH. Researchers have shown that light annual applications of lime (20 to 25 lbs. per 1000 square feet) may be beneficial in speeding the thatch decomposition rate. Moderate use of nitrogen with more frequent small applications appears to decrease thatch buildup. Aerification and topdressing of turfgrass speeds up thatch decomposition by returning microbes into the thatch layer and improving the environment for their maximum activity. Aerobic microorganisms involved in the thatch decomposition benefit from improved oxygen levels as much as the turfgrass. Earthworm castings serve to inoculate the thatch layer with microorganisms and soil to improve moisture retention in the thatch layer, thus increasing microbial activity.

If the thatch layer in your lawn is more than 2 inches thick, dethatching and/or aeration will be beneficial. Timing of these is critical, and is best done during periods when the plants can recover from the treatment. Warm-season grasses should be dethatched in early to mid-summer. Kentucky bluegrass and other cool-season grass lawns should be dethatched in early fall or early spring. Spring verticutting can lead to excessive crabgrass invasion if improperly timed. Vertical mowers and aerifiers can be rented. Dethatchers physically remove thatch and deposit it on the surface of the lawn. This material should then be raked up and removed. If overseeding is planned, it is good to do this in conjunction with the verticutting or aerating process, since the grooves cut in the soil will provide good soil contact for the new seed.

pH Adjustment

Soils in Virginia are typically acid, and from time to time it may be necessary to add lime in order to keep the soil pH near 6.2. Soil test results will tell how much lime should be applied.

Aeration

If soil is heavy or compacted, or thatch buildup is a problem, aeration may be necessary. Roots need oxygen as well as water and nutrients. Compacted soil restricts the absorption of water and does not allow the soil to exchange oxygen with the atmosphere.

Aeration is best done by a machine which forces hollow metal tubes into the ground and brings up small cores of soil which are left laying on the surface. The soil should be moist, not too wet or too dry, when this is done. Simply punching holes with a spiked roller may improve water retention, but this practice also increases compaction in the soil. Reinoculation of thatch layers with soil and microbes through the aeration process is beneficial in helping to create an environment conducive to thatch decomposition. Another great soil improvement strategy to tie together with core aeration is a surface application of compost. As little as ¼ inch depth of compost one to two times per year is an important way to improve soil physical and chemical properties and reduce fertilizer, water, and pesticide water inputs for the turf over time.

Disease Control

Proper management will greatly reduce a lawn’s susceptibility to disease. Disease damage may be difficult to identify, since many of the symptoms may also be caused by improper management or by environmental factors such as competition from tree roots. Nearly all lawn diseases are caused by fungi, and fungicides can be applied to prevent and control them.

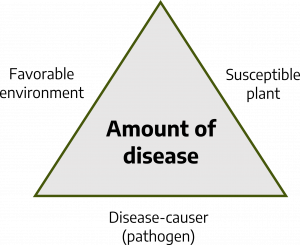

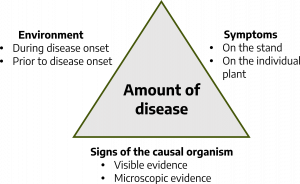

Disease or sickness in turfgrasses, as in other plants, develops from an interaction between a susceptible plant, a disease-producing organism (usually a fungus), and an environment favorable for the disease-causing organism to attack. Scientists who work with turfgrass diseases sometimes use a disease triangle to illustrate the concept of disease. The three sides of the disease triangle represent three factors that interact to produce turfgrass disease: the disease causer, the susceptible grass, and a favorable environment (Figure 11-5). Three factors interact to cause turfgrass disease; therefore we must observe all three factors to gather information for diagnosis of the problem, and we can change any or all of these three factors to combat the disease.

The first step in turfgrass disease management is the identification of the problem. Disease management strategies that are effective against one disease may have no effect on or may even worsen another disease.

The three factors (grass, disease-causer, and environment) provide the sources of information for diagnosis (Figure 11-6). The environment during the onset of the disease is one source of diagnostic information. For example, what were the temperature, the light intensity, and the moisture conditions just prior to and during disease development? The nature of the disease site is also important. Air and water drainage, soil conditions, sun/shade, slope, and nearness of other plantings or buildings may all be important in development of turfgrass diseases. Prior chemical applications to the site, including pesticides and fertilizers, may be contributive. Heavy thatch accumulation and poor mowing practices that stress the turf may trigger or amplify certain disease problems in turf areas.

The nature of the symptoms on the grass is a very important source of diagnostic information. Two kinds of symptoms should be looked for in diseased turfgrass areas- symptoms on the stand, and symptoms on individual plants. A home lawn, an athletic field, and a golf green or fairway are all examples of turf stands. Symptoms on the stand are the appearance and the visible patterns of the disease on the planting. These are extremely important in turfgrass disease diagnosis because different diseases appear differently on turf stands. The visible differences in pattern are often critical factors in identifying particular diseases. Diseases can appear on the turf stand as spots, patches, rings, circles, or may be unpatterned. Certain diseases never appear as rings, while others always appear as rings. Symptoms to look for on individual plants include leaf spots, leaf blight, wilt, stunt, yellowing, and root discoloration or rot. Leaf spots can be very good diagnostic clues because the leaf spots of diseases are usually unique in shape, color, and size. Leaf blighting is different from these unique leaf spots because leaf blighting is rot on the leaf that has no definite form. Leaf blighting can be any size or shape and may involve the entire leaf.

Certain life stages of turfgrass disease-causers can be seen without magnification. The fungi that cause most turfgrass diseases are microscopic. But in stripe smut, powdery mildew, and rust diseases, that spores of the causal fungi pile up in such numbers that they become visible as black, white, or orange powder on grass leaves. In red thread disease, the fungus sticks together and forms the pink or red antler-like threads that typify the disease. When the causal fungus can be seen, its appearance is often the most important clue for diagnosis.

Because the three components of disease development combine to influence the onset of turfgrass disease, the task of disease management on turfgrasses involves manipulation of these three – the environment, the grass, and/or the disease-causing organism – to favor the grass and inhibit the causal fungus.

The environment can be altered in many ways. The ones chosen depend on the disease to be managed. Water manipulation can be a valuable tool in disease management. Effective strategies to reduce free water include morning irrigation, removal of dew, and reduction in amount and/or frequency of irrigation. Other management strategies may involve some forms of improved air and water drainage, improved soil conditions by aeration, thatch reduction, manipulation of light conditions, regulation of fertilization levels, and implementation of proper mowing practices.

When establishing new turf areas or when renovating disease-damaged turf, it is important to select grasses that are resistant to diseases known to be common in the area or that have damaged the existing stand. Disease resistant grasses can be seeded to minimize turf loss from disease. Disease severity can often be reduced by appropriate changes in the grass that is being grown. It is a bad practice to replant that same grass that has been killed by the same disease year after year, if there is another option. In selecting grasses for turf establishment or renovation, it is preferable, where possible, to use mixtures of different grasses or blends of different varieties rather than seeding a single kind of grass. The seeding of mixtures or blends produces a diverse population of grass plants. Such turf is usually more likely to survive stress caused by disease. Diversity in plantings almost always increases odds of survival.

The causal organism may be attacked by applying chemicals that will either kill the organism or keep it from growing. Again, it is important to have identified the causal organism correctly, so that an appropriate fungicide can be selected. Arbitrary selection and application of fungicides without knowledge of the disease can do as much harm as good. Using the wrong fungicide wastes money, and may increase the amount of disease or produce other undesirable side effects.

Planning an effective disease management program involves not only “spraying something,” but selecting cost effective and environmentally sound disease control strategies. The financial, environmental, and aesthetic costs of disease management strategies must be considered. Good, common sense approaches to disease management should employ all available disease management strategies.

The Virginia Tech Disease Diagnostic Lab provides identification services for samples that are handled through local Virginia Cooperative Extension offices.

Insect Control

There are naturally many different types of insects present in a lawn. Most of these are not harmful to the grass. Control for insects is not necessary unless the pest population builds up enough to cause visible damage to the lawn.

Close examination on hands and knees is the best way to identify insect pests in a damaged lawn. You may be able to see the insect in action. If you think you have an insect problem, your local Extension Office can help in identifying the pest and suggesting recommended control measures.

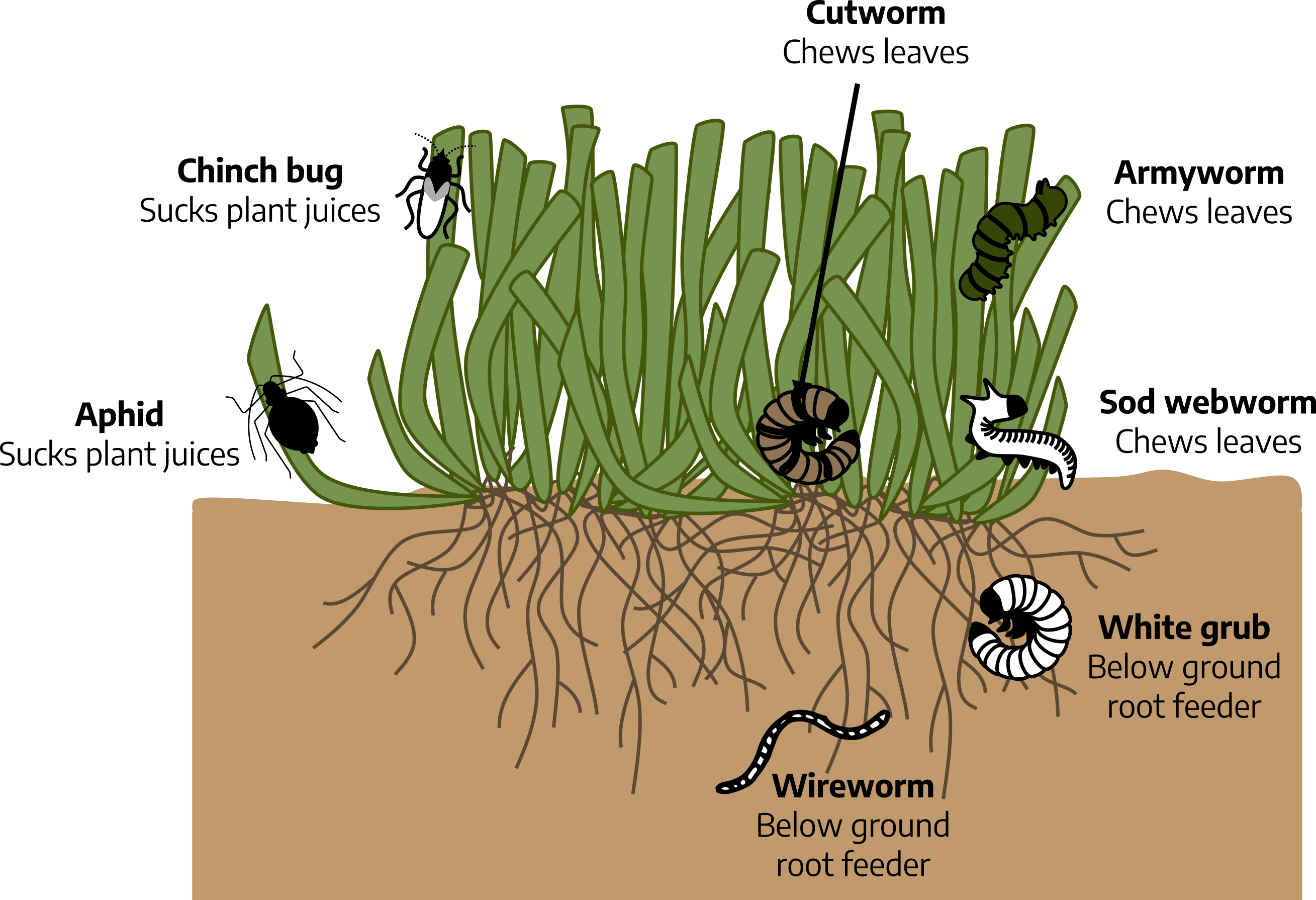

The most common above-ground insect pests in Virginia lawns are chinch bugs and sod webworms which feed on grass leaves and stems. Below ground, the most common pests are white grub larvae which feed on roots.