6.7 Stuck in the Middle

A firm is said to be stuck in the middle if it does not offer features that are unique enough to convince customers to buy its offerings and its prices are too high to effectively compete based on price. Firms that are stuck in the middle generally perform poorly because they lack a clear market or competitive pricing. Several examples of such firms are illustrated below.

| Examples of Firms that are Stuck in the Middle |

| Arby’s signature roast beef sandwiches are neither cheaper than other fast food nor are they standouts in taste. |

| Sears and their famous catalog once dominated US retailing, but the failure to cultivate customers among newer generations and prices that are higher than those of rivals have severely wounded the company. Sears filed for bankruptcy in 2018. |

| Electronics retailer Circuit City found itself squeezed by the superior service offered by rival Best Buy and the cheaper prices charged on electronics by Walmart and Target. Headquartered in Richmond, Virginia, the firm went bankrupt in 2009 after sixty years in business. |

| Kmart’s “Blue Light Specials” that alert shoppers to a deeply discounted item reflect the firm’s long-running effort to be a cost leader. But emerging on the losing end of a price war with Walmart sent the firm into bankruptcy. Struggling to survive, it has closed most of its stores. |

Stuck in the Middle: Neither Inexpensive nor Differentiated

Some firms fail to effectively pursue one of the generic strategies. A firm is said to be stuck in the middle if it does not offer features that are unique enough to convince customers to buy its offerings, and its prices are too high to compete effectively based on price (Table 6.11). Arby’s appears to be a good example. Arby’s signature roast beef sandwiches are neither cheaper than other fast-food sandwiches nor standouts in taste. Firms that are stuck in the middle generally perform poorly because they lack a clear market or competitive pricing.

Doing Everything Means Doing Nothing Well

Michael Porter has noted that strategy is as much about executives deciding what a firm is not going to do as it is about deciding what the firm is going to do (Porter, 1996). In other words, a firm’s business-level strategy should not involve trying to serve the varied needs of different segments of customers in an industry. No firm could possibly pull this off.

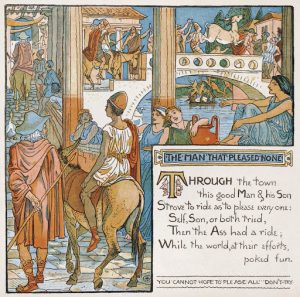

The fable, The Miller, His Son, and Their Ass, told by the ancient Greek storyteller Aesop helps illustrate this idea. In this tale, a miller and his son were driving their ass (donkey) to market for sale. They soon encountered a group of girls who mocked them for walking instead of riding. The father then told his son to ride the animal. Not long after, father and son overheard a man claim that young people had no respect for the elderly. On hearing this opinion, the father told the boy to dismount the animal and he began to ride. They progressed a short distance farther and met a company of women and children. Several of the women suggested that it was both ridiculous and lazy for the father to ride while the young son was forced to walk alone; once again the two changed positions. Another bystander suggested that they could not believe that the man was the owner of the beast, judging from the way it was weighed down. In fact, it would make more sense for the man and his son to carry the ass. On hearing this, the father and his son tied the animal’s legs together and carried it on a pole. As they crossed a bridge near town, the townspeople began to gather and laugh at the unorthodox sight. The noise and the chaos frightened the beast, leading it to thrash around until it tumbled into the river. With tongue in cheek, we note that the moral of the story is that if you try to please everyone, you may lose your ass (Short & Ketchen, 2005).

Getting Outmaneuvered by Competitors

In many cases, firms become stuck in the middle not because executives fail to arrive at a well-defined strategy but because firms are simply outmaneuvered by their rivals. After six decades as an electronics retailer, Circuit City went out of business in 2009. The firm had simply lost its appeal to customers. Rival electronics retailer Best Buy offered comparable prices to Circuit City’s prices, but the former offered much better customer service. Meanwhile, the service offered by discount retailers such as Walmart and Target on electronics was no better than Circuit City’s, but their prices were better.

The results were predictable—customers who made electronics purchases based on the service they received went to Best Buy, and value-driven buyers patronized Walmart and Target. Circuit City’s demise was probably inevitable because it lacked a competitive advantage within the electronics business. Although Target was on the winning end of this battle, Target executives need to worry that their firm could become stuck in the middle between Walmart’s better prices on one side and the trendiness of specialty shops on the other.

IBM’s personal computer business offers another example. IBM tried to position its personal computers via a differentiation strategy. In particular, IBM’s personal computers were offered at high prices, and the firm promised to offer excellent service to customers in return. Unfortunately for IBM, rivals such as Dell were able to provide equal levels of service while selling computers at lower prices. Nothing made IBM’s computers stand out from the crowd, and the firm eventually exited the business.

At its peak in the mid-2000’s, Blockbuster operated approximately 9,000 video rental stores. By 2010, the firm filed for bankruptcy. This rapid demise can be traced to the firm becoming outmaneuvered by Netflix. When Netflix began offering inexpensive DVD rentals through the mail, customers defected in droves from Blockbuster and other video rental stores such as Movie Gallery. Netflix customers were delighted by the firm’s low prices, vast selection, the convenience of not having to visit a store to select and return videos, and were among the first to transition to streaming movies. The low price strategy of RedBox also hurt the firm. Blockbuster was stuck in the middle—its prices were higher than those of Redbox and Netflix, and Netflix’s service was superior. Once individuals lacked a compelling reason to be Blockbuster customers, the firm’s fate was sealed. As of 2020 Blockbuster operated one store!

Key Takeaway

- When executing a business-level strategy, a firm must not become stuck in the middle between viable generic business-level strategies by neither offering unique features nor competitive pricing.

Exercises

- What is an example of a firm that you would consider to be “stuck in the middle”? What would your advice be to the executives in charge of this firm?

- Research a company that has gone bankrupt or otherwise stopped operations in the past decade because their strategy was “stuck in the middle” of otherwise viable generic business-level strategies. Could its demise have been prevented?

References

Porter, M. E. (1996). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, reprint 96608.

Short, J. C., & Ketchen, D. J. (2005). Using classic literature to teach timeless truths: An illustration using Aesop’s fables to teach strategic management. Journal of Management Education, 29(6), 816–832.

Image Credits

Figure 6.12: Crane, Walter. “Illustration for ‘The Man That Pleased None.'” Public Domain. Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a5/Can%27t_please_everyone2.jpg.

Figure 6.13: Stu pendousmat. “A Blockbuster location in Moncton.” CC BY-SA 3.0. Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/35/BlockbusterMoncton.JPG.