11.4 Corporate Ethics and Social Responsibility

What Is Corporate Social Responsibility?

As introduced early in this chapter, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) “is a self-regulating business model that helps a company be socially accountable—to itself, its stakeholders, and the public. By practicing corporate social responsibility, also referred to simply as social responsibility, companies can be conscious of the kind of impact they are having on all aspects of society, including economic, social, and environmental” (Chen, 2020). Philanthropy is the simplest form of CSR, where a firm donates funds to a nonprofit organization such as the local volunteer rescue squad or the American Cancer Society. However, CSR can take many forms, with the end result that society benefits in some way. Environmental efforts in CSR might include reducing the company’s pollution or helping to clean up the plastic that washes up on beaches. Supporting the local literacy volunteers by encouraging employees to participate to help adults learn to read and write provides a social benefit.

The CSR approach is not without controversy. When CSR was introduced, the famous economist Milton Friedman opposed CSR on philosophical grounds. He believed, as some others did, that no profits should be diverted for CSR activities. The logic was that company investors and stockholders took a risk when they invested in the company, and therefore the company’s first obligation is to them. On the other hand, many who practice CSR believe that CSR activities ultimately do benefit the company investors and stockholders. The belief is that having a CSR strategy provides good public relations for the firm and enhances their brand image, creating loyalty and more sales long term. For example, some consumers may specifically shop for TOMS shoes because of the firm’s Buy One, Give One model, where the consumer feels their purchase is providing a positive social impact.

Some examples of CSR efforts are:

- Reducing their carbon footprint—Coca Cola

- Ensuring contract manufacturers pay a living wage—Patagonia

- Improving sustainable manufacturing—BMW

- Matches employees’ donations to nonprofits—Microsoft and Google

- Reducing carbon emissions—United Airlines

- Promoting literacy among children—Twitter

- Eliminating foam cups—Dunkin’

- Donating employees’ hours to children’s tutoring—Salesforce

One criticism of CSR is that it is seen as an “add on” endeavor for firms. Often, CSR is not an ingrained component of the firm’s philosophy and operations. In response to this criticism, a rather new movement emerged in an attempt to remedy this deficiency. Michael Porter and Mark Kramer suggest that instead of CSR, wise corporations are shifting to a Creating Shared Value (CSV) model that argues that firms should address social issues by creating shared value, which is fundamentally focused on expanding the total pool of social and economic resources (Porter & Kramer, 2006; Porter & Kramer, 2011). Porter and Kramer re-frame the business proposition by trying to recognize that “societal needs, not just conventional economic needs, define markets, and social harms can create internal costs for firms” (Porter & Kramer, 2011).

Creating shared value (CSV) is a business strategy that creates a direct link between the success of the firm and the improvement of society. Generally, CSV can be considered to be a particular strategic approach within the more general CSR landscape. A key differentiating detail is the explicit focus of CSV in generating positive economic outcomes through its strategic investments. As a company prospers economically, so do those it impacts. However, CSV and CSR both take a longer-term, rather than a short-term, approach to measuring impact. For example, Whole Foods was one of the most high profile companies to adopt CSV as a guiding strategy. This strategy translated into investing in local schools to ensure a well prepared work force and supporting local agricultural communities so it could reliably source produce from local vendors. While one traditional view of “business as usual” is that when a company prospers, it is at the expense of the consumer and society. CSV and CSR flip this view.

Section Videos

Business Ethics: Corporate Social Responsibility [02:56]

The video for this lesson further explains corporate social responsibility.

You can view this video here: https://youtu.be/xoE8XlcDUI8.

Insight: Ideas for Change—Michael Porter—Creating Shared Value [14:09]

The video for this lesson focuses on the differences between CSR and CSV.

You can view this video here: https://youtu.be/xuG-1wYHOjY.

Measuring Corporate Social Performance

TOMS Shoes’ commitment to donating a pair of shoes for every pair sold illustrates the concept of social entrepreneurship, in which a business is created with a goal of improving both business and society (Schectman, 2010). Using a CSR model, firms such as TOMS exemplify a desire to improve corporate social performance (CSP) in which a commitment to individuals, communities, and the natural environment is valued alongside the goal of creating economic value. Although determining the level of a firm’s social responsibility is subjective, this challenge has been addressed by other organizations that rate firms on a number of stakeholder-related issues with the goal of measuring CSP. They conduct ongoing research on social, governance, and environmental performance metrics of publicly traded firms and reports such statistics to institutional investors. For example, the KLD database provides ratings on numerous “strengths” and “concerns” for each firm along a number of dimensions associated with corporate social performance (Table 11.6 “Measuring Corporate Social Performance”). The results of their assessment are used to develop the Domini social investments fund, which has performed at levels roughly equivalent to the S&P 500. Some rating firms use an ESG framework for evaluating a firm. ESG stands for Environmental, Social, and Governance, and measures within each of these three dimensions are used to score a company.

Corporate social performance is defined as the degree to which a firm’s actions honor ethical values that respect individuals, communities, and the natural environment. Determining whether a firm is socially responsible is somewhat subjective, but one popular approach has been developed by KLD Research & Analytics. Their work tracks “strengths” and “concerns” for hundreds of firms over time. KLD’s findings are used by investors to screen socially responsible firms and by scholars who are interested in explaining corporate social performance. We illustrate the six key dimensions tracked by KLD below.

| Corporate Social Performance | ||

| Community strengths include engagement in charitable giving, while involvement in tax controversies exemplifies a community concern. | Product quality/safety strengths include actions such as the establishment of a well-developed quality program, while concerns arise if a firm receives fines related to product quality and/or safety. | Diversity strengths include progressive programs for the employment of persons with disabilities, whereas fines or civil penalties that result from an affirmative action constitute a concern. |

| A no-layoff policy is a strength in regard to employee relations, while poor union relations are a concern. | Environmental strengths include engaging in recycling, while concerns arise when penalties for air or water violations are documented. | Corporate governance strengths include equitable levels of compensation for top management and board members, while concerns are raised if controversies related to accounting, transparency, or political accountability are discovered. |

Assessing the community dimension of CSP is accomplished by assessing community strengths, such as charitable or innovative giving that supports housing, education, or relations with indigenous peoples, as well as charitable efforts worldwide, such as volunteer efforts or in-kind giving. A firm’s CSP rating is lowered when a firm is involved in tax controversies or other negative actions that affect the community, such as plant closings that can negatively affect property values.

CSP diversity strengths are scored positively when the company is known for promoting women and minorities, especially for board membership and the CEO position. Employment of persons with disabilities and the presence of family benefits such as child or elder care would also result in a positive score by KLD. Diversity concerns include fines or civil penalties in conjunction with an affirmative action or other diversity-related controversy. Lack of representation by women on top management positions—suggesting that a glass ceiling is present at a company—would also negatively impact scoring on this dimension.

The employee relations dimension of CSP gauges potential strengths such as notable union relations, profit sharing and employee stock-option plans, favorable retirement benefits, and positive health and safety programs noted by the US Occupational Health and Safety Administration. Employee relations concerns would be evident in poor union relations, as well as fines paid due to violations of health and safety standards. Substantial workforce reductions as well as concerns about adequate funding of pension plans also warrant concern for this dimension.

The environmental dimension records strengths by examining engagement in recycling, preventing pollution, or using alternative energies. KLD would also score a firm positively if profits derived from environmental products or services were a part of the company’s business. Environmental concerns such as penalties for hazardous waste, air, water, or other violations or actions such as the production of goods or services that could negatively impact the environment would reduce a firm’s CSP score.

Product quality/safety strengths exist when a firm has an established and/or recognized quality program; product quality safety concerns are evident when fines related to product quality and/or safety have been discovered or when a firm has been engaged in questionable marketing practices or paid fines related to antitrust practices or price fixing.

Corporate governance strengths are evident when lower levels of compensation for top management and board members exist, or when the firm owns considerable interest in another company rated favorably by KLD; corporate governance concerns arise when executive compensation is high or when controversies related to accounting, transparency, or political accountability exist.

Key Takeaway

- Many companies have adopted a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) philosophy to make improvements in the communities and society they operate. CSR is evolving to a Creating Shared Value (CSV) model which integrates the profit motive with solving social issues. Firms such as KLD provide objective measures of both positive and negative actions related to corporate social performance.

Exercises

- How would your college or university fare if rated on the dimensions of CSR? Of CSV?

- Do you believe that executives behave more ethically as a result of legislation such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act? Why or why not?

References

Chen, J. (2020, February 22). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/corp-social-responsibility.asp.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78-92.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating Shared Value. Harvard Business Review.

Schectman, J. (2010). Good Business. Newsweek, 156, 50.

Image Credits

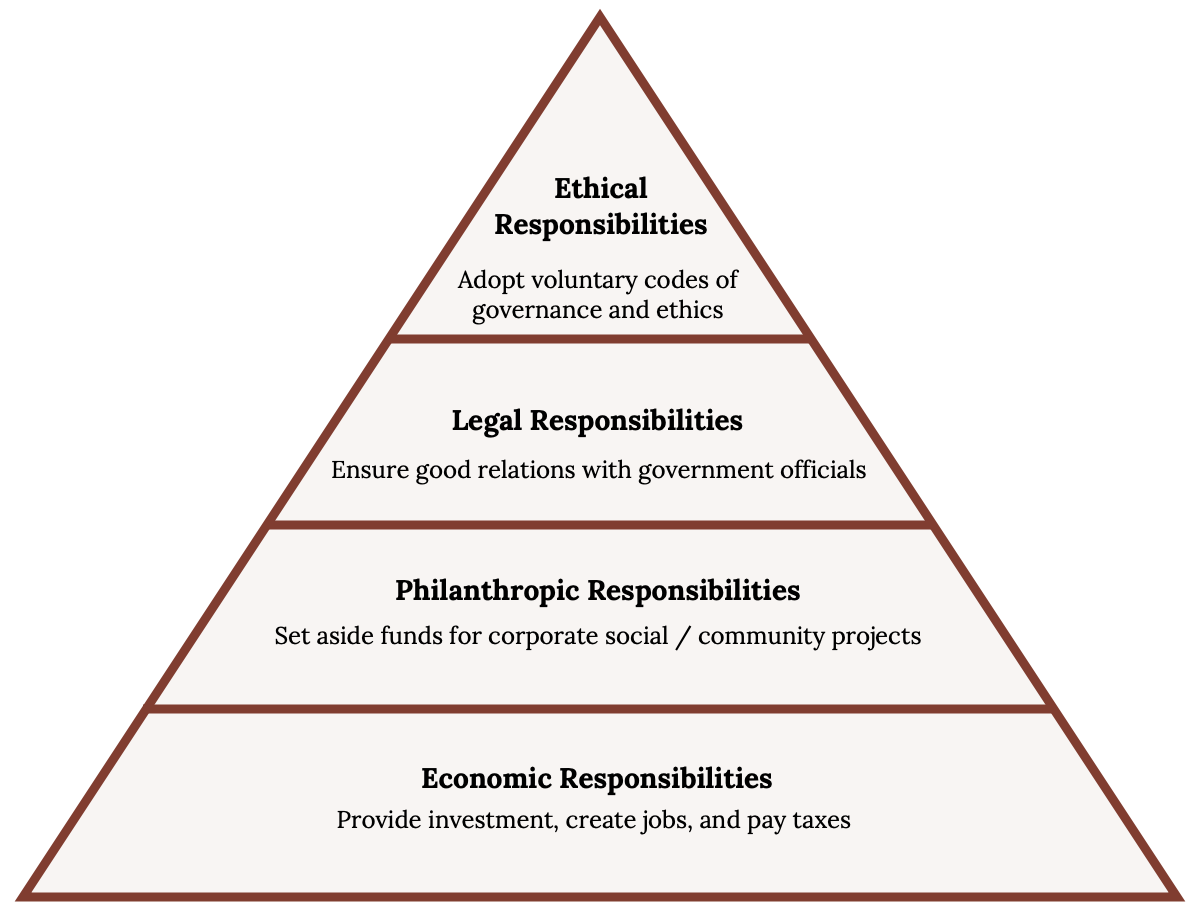

Figure 11.3: Kindred Grey (2020). “Business responsibilities.” CC BY-SA 4.0. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Business_responsibilities.png.

Figure 11.4: Chick-fil A. (2020). Photo used under Fair Use. Scholarship winners. Retrieved from https://thechickenwire.chick-fil-a.com/news/chick-fil-a-to-award-17-million-in-team-member-scholarships-in-2020.

Video Credits

Study.com. (2013, December 31). Business Ethics: Corporate Social Responsibility. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/xoE8XlcDUI8.

World Economic Forum. (2012, September 6). Insight: Ideas for Change-Michael Porter-Creating Shared Value. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/xuG-1wYHOjY.

Efforts by a firm to be socially accountable by contributing to community and/or societal goals through philanthropic, activist, or charitable activities

A business model whereby society’s needs and challenges are addressed as a firm prospers achieving its mission

Measuring the impact of a firm’s activities in corporate social responsibility