3 Stakeholder Motivations for Sustainable Property Management Practices

Chapter Contents

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Building Owners

3.3 Property Management Companies

3.4 Tenants

3.5 Vendors

3.6 Communities

3.7 Conclusion

Learning Objectives

- Identify key stakeholders in sustainable property management operations

- Identify motivations for building owners to adopt sustainable property management practices

- Identify motivations for property management companies to adopt sustainable property management practices

- Identify motivations for tenants to adopt sustainable property management practices

- Identify motivations for vendors to adopt sustainable property management practices

- Identify motivations for communities to adopt sustainable property management practices

3.1 Introduction

Various stakeholders significantly influence sustainable property management implementation. By understanding their motivations for sustainable building operations, an appropriate strategy can be devised that addresses their particular needs. Motivations can vary among stakeholders, so it is important to develop the sustainable property management plan based on the goals that are important to that particular stakeholder. This chapter identifies key stakeholders in sustainable property operations as illustrated in figure 3.1 and some common motivations for each stakeholder. Collaboration among stakeholders is key during this process of getting everyone on board with a sustainable property management plan.

3.2 Building Owners

The building owner typically holds the most influence over sustainable building initiative decisions. Although property management companies occasionally come to building owners pitching sustainable property management initiatives, more building owners influence property management companies to adopt sustainable building practices at this point and time. Figure 3.2 depicts common motivating factors for pursuing sustainable building initiatives from a building owner perspective.

Local laws and regulations motivate building owners to engage with sustainable property management. The Clean Energy Omnibus Amendment Act of 2018 enacted in Washington DC is an example where commercial and multifamily buildings under a certain energy threshold must improve their performance by 20 percent over a five-year compliance period or undertake other prescriptive measures (Department of Energy & Environment, n.d.). This mandates that building owners engage with sustainable building management practices. Some building owners also experience pressure from investors and the marketplace to implement ESG policies, as well as face reporting requirements based on these implemented ESG policies. Some investors and consumers simply will not invest with a building owner that does not have ESG policies and procedures in place. This is evidenced by the results of the PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) 2021 Global Investor ESG Survey where 49 percent of respondents “express willingness to divest from companies that aren’t taking sufficient action on ESG issues” (PriceWaterhouseCoopers, 2021).

One popular method that building owners use to incorporate ESG policies are green building certifications and the GRESB framework. These frameworks can assist building owners to more easily engage in sustainable property management practices by providing a pathway toward sustainable property management at the real estate asset level and organizational level. These certifications also provide an opportunity for asset distinction and enhanced market image. They may even be a recruiting tool, especially for younger generations who may be more aligned with sustainable building concepts.

Some business owners who may not necessarily care about sustainable building concepts engage with these concepts due to the potential positive financial statement impacts. For example, there is a law in Virginia that allows local jurisdictions to offer a reduced local property tax rate for buildings that reach a specific energy efficiency threshold (Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency, 2020). Historically, research has found that eco labels have economic benefits such as higher rents, higher occupancy, and increased sales prices. Specifically, green certified buildings garner 2.5–8.9 percent higher rents, increased occupancy rates of 3–11 percent, and 5.76–26 percent higher sales price in the commercial sector (Eichholtz, Kok, & Quigley, 2010; Fuerst & McAllister, 2009, 2011; Miller, Spivey, & Florance, 2008; Reichardt, Fuerst, Rottke, & Zietz, 2012; Stanley & Wang, 2017; Wachter, n.d.; Wiley, Benefield, & Johnson, 2010). Research has also generally shown operating cost savings such as greater energy and water efficiency in green buildings compared to conventional buildings (Hopkins, 2016). That is not to say that all green certified buildings act in this manner. For example, research has also found some green certified buildings consume more energy than non-certified buildings (Menassa, Mangasarian, El Asmar, & Kirar, 2011; Newsham, Mancini, & Birt, 2009; Oates & Sullivan, 2011). This showcases building variability and the need to assess each building for the appropriate green building initiatives based on its features. Some building owners also adhere to an environmentally conscientious corporate agenda to tap into their desire to “do good” for the environment. This type of agenda engages building owners with sustainable property management to keep them on the path of being more environmentally friendly.

It should be noted that there are barriers to sustainable property management initiatives from the perspective of the building owner. The uncertainty in time and cost to implement sustainable initiatives as well as the lack of market demand in some markets create a disincentive for property owners to invest in sustainable measures (Kriese & Scholz, 2011; Kyrö et al., 2012; Miller & Buys, 2008). Another deterrent faced by building owners is the investment in energy efficient appliances and fixtures if the tenant pays for their own utilities and the tenants’ cost savings are not fully capitalized into the rental rate (Blumstein et al., 1980; Davis, 2011; Klein, Drucker, & Vizzier, 2009; Economidou, 2014).

Section References

Blumstein, C., Krieg, B., Schipper, L., & York, C. (1980). Overcoming social and institutional barriers to energy conservation. Energy, 5(4), 355–371.

Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency (2020, June 29). Local option—Property tax assessment for energy efficient buildings. https://programs.dsireusa.org/system/program/detail/2983

Davis, L. W. (2011). Evaluating the slow adoption of energy efficient investments: Are renters less likely to have energy efficient appliances? In D. Fullerton and C. Wolfram (Eds.), The design and implementation of U.S. climate policy (pp. 301–316). University of Chicago Press.

Department of Energy & Environment (2023, February). Clean energy DC omnibus amendment act. https://doee.dc.gov/service/clean-energy-dc-act

Economidou, M. (2014). Overcoming the split incentive barrier in the building sector (workshop summary). Publications Office of the European Union. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC90407

Eichholtz, P., Kok, N., & Quigley, J. M. (2010). Doing well by doing good? Green office buildings. The American Economic Review, 100(5), 2492–2509.

Fuerst, F., & McAllister, P. (2009). An investigation of the effect of eco-labeling on office occupancy rates. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 1(1), 49–64.

Fuerst, F., & McAllister, P. (2011). Green noise or green value? Measuring the effects of environmental certification on office values. Real Estate Economics, 39(1), 45–69.

Hopkins, E. A. (2016). An exploration of green building costs and benefits: Searching for the higher ed context. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 24(1), 67–84.

Klein, J., Drucker, A., & Vizzier, K. (2009). A practical guide to green real estate management. Institute of Real Estate Management.

Kriese, U., & Scholz, R. W. (2011). The positioning of sustainability within residential property marketing. Urban Studies, 48(7), 1503–1527.

Kyrö, R., Heinonen, J., & Junnila, S. (2012). Housing managers key to reducing the greenhouse gas emissions of multi-family housing companies? A mixed method approach. Building and Environment, 56, 203–210.

Menassa, C., Mangasarian, S., El Asmar, M., & Kirar, C. (2011). Energy consumption evaluation of U.S. Navy LEED-certified buildings. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, 26(1), 46–53.

Miller, E., & Buys, L. (2008). Retrofitting commercial office buildings for sustainability: Tenants’ perspectives. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 26(6), 552–561.

Miller, N., Spivey, J., & Florance, A. (2008). Does green pay off? Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 14(4), 385–400.

Newsham, G. R., Mancini, S., & Birt, B. J. (2009). Do LEED-certified buildings save energy? Yes, but…. Energy and Buildings, 41(8), 897–905.

Oates, D., & Sullivan, K. T. (2011). Postoccupancy energy consumption survey of Arizona’s LEED new construction population. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 138(6), 742–750.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2021, October 28). Companies failing to act on ESG issues risk losing investors, finds new PwC survey. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/news-room/press-releases/2021/pwc-esg-investor-survey-2021.html

Reichardt, A., Fuerst, F., Rottke, N., & Zietz, J. (2012). Sustainable building certification and the rent premium: A panel data approach. Journal of Real Estate Research, 34(1), 99–126.

Stanley, J., & Wang, Y. (2017). An analysis of LEED certification and rent effects in existing U.S. office buildings. In N. E. Coulsen, Y. Wang & C. A. Lipscomb (Eds.), Energy Efficiency and the Future of Real Estate (pp. 99–136). Palgrave Macmillan.

Wachter, S. (2013). Valuing energy efficient buildings. http://www.cbei.psu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Valuing-Energy-Efficient-Buildings.pdf&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1678218728093622&usg=AOvVaw18xZwhvX7Lq2RkxnhORSqD

Wiley, J. A., Benefield, J. D., & Johnson, K. H. (2010). Green design and the market for commercial office space. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 41(2), 228–243.

3.3 Property Management Companies

Figure 3.3 illustrates some common motivating factors for pursuing sustainable building initiatives from a property management company perspective.

In some cases, there are sustainable property management responsibilities outlined in the management agreement. Examples may include the requirement of ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager reporting, and managing maintenance in a way that optimizes energy efficiency, such as wiping down coils at specific intervals to optimize efficiency, avoiding heating pools above 79 degrees to minimize evaporation, or only using LED light bulbs when light bulbs need to be replaced. It can be helpful for property managers to create and regularly update a sustainable property management plan that incorporates these responsibilities as well as other items deemed important by various stakeholders to run the property more sustainably while also aligning with property ownership goals.

The incorporation of conservation practices into performance expectations and/or annual performance evaluations is another motivating factor for property management companies to engage with sustainable property management principles. If sustainable property management concepts are part of performance expectations and subsequent performance evaluations, employees will very likely take these concepts seriously and work toward implementation throughout the property. While sustainable property management responsibilities are not widely incorporated into the management agreement and the employee evaluation process just yet, it is something to consider in order to increase sustainable property management practices at the real estate asset.

There are also potential positive leasing impacts for buildings that are managed in a sustainable manner. Showcasing sustainable initiatives can potentially make units easier to lease and make the building more in demand in a market that views sustainable building practices as important. Sustainable property management can also translate into higher property management fees due to this increase in lease activity. This is because property management fees are commonly based on rental income figures. Property owners can also incentivize property managers to reduce operating costs through sustainable measures by basing the management fee on operating expenses as well.

While it is true that property managers have a plethora of responsibilities and this may seem like “just one more thing to do“ in some cases, effectively embedding sustainable property management responsibilities into property management operations can benefit the property manager from a marketing, financial, risk management, and maintenance perspective. In reality, these practices can help them in their jobs and may help them to achieve certain thresholds for financial incentives and bonuses. However, barriers to engagement with sustainable practices persist in the property management industry, such as trepidation about new sustainable technologies and the lack of systems to properly evaluate the costs and benefits of sustainable building measures (Epstein & Roy, 2003; Pinkse & Dommisse, 2009).

Section References

Epstein, M. J., & Roy, M. J. (2003). Making the business case for sustainability. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2003(9), 79-96.

Pinkse, J., & Dommisse, M. (2009). Overcoming barriers to sustainability: An explanation of residential builders’ reluctance to adopt clean technologies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 18(8), 515-527.

3.4 Tenants

Figure 3.4 depicts various common motivating factors for pursuing sustainable building initiatives from a tenant perspective.

Enhanced well-being is a motivating factor for tenants to engage with sustainable property management practices. Examples of tenants engaging with sustainable property management practices for well-being purposes include taking advantage of physical, mental, and social health opportunities at the building, waiting to run the dishwasher or do laundry until there is a full load to save on utility costs, and not smoking. Tenant education programs can help tenants learn about ways to incorporate sustainable property management practices on a regular basis. Program examples include a handbook for tenants, programming on site for tenants, as well as signage throughout the property. Content can be created by the property management firm or drawn from other sources such as Better Buildings, an initiative of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Information about how each initiative helps meet goals for all three spheres of sustainability fosters action on the part of the tenant. Also, statistics can help motivate tenants to act. For example, instead of just asking tenants to unplug their appliances and devices while not in use, the statistic that plug loads can account for 30 percent of building energy, and equating this percentage to money saved and GHG emission reductions, can be used (EPA, n.d.). A tenant education program can also include real-time energy and water monitoring, as illustrated in figure 3.5, to help engage tenants in reducing their consumption.

Rewards are another tool to engage residents in sustainable property management practices. For example, contests relating to reducing consumption can be part of the real-time monitoring building display and rewards given for reaching certain goals. Recycling campaigns can also be implemented with rewards such as a gift card, free food, or a reusable water bottle when certain recycling thresholds are met. Recognition can also be used as a reward if there are limited funds available. Lower utility costs also motivate tenants to engage with sustainable property management principles. Partnering with tenants to educate them on how to reduce their utility bills through sustainable practices can help the tenant save money, reduce GHG emissions, and foster relationships between the tenant and property manager.

Of course lower utility bills is only a motivating factor if the tenant pays for their own utilities. In some cases, the building owner pays for the utilities so this motivating factor would be irrelevant. There are also other barriers to tenant engagement. For example, a busy single parent working two jobs may not reasonably have the time to unplug unused appliances or follow other green tenant practices; similarly, it may not be safe or even physically possible for elderly residents in a retirement community apartment tower to reach down to unplug things.

Section Reference

EPA (n.d.). 8 Great strategies to engage tenants on energy efficiency. https://betterbuildingssolutioncenter.energy.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/8-Great-Strategies-to-Engage-Tenants.pdf

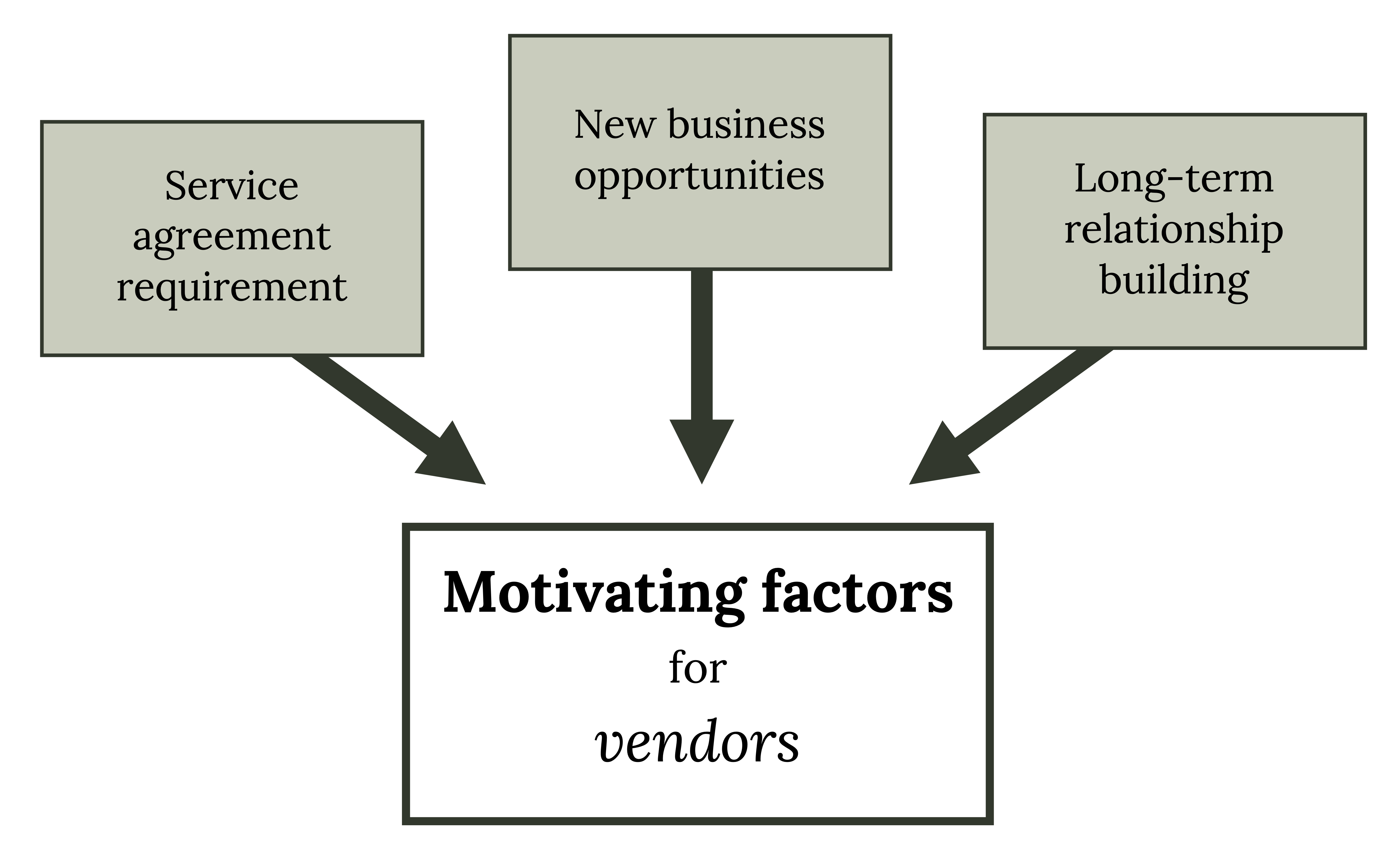

3.5 Vendors

Property vendors include contractors and suppliers. Figure 3.6 illustrates some common motivating factors for pursuing sustainable building initiatives from a vendor perspective.

The property owner may require vendors adhere to certain sustainability standards for operations at the property. These requirements can be detailed out in the service agreement between the property manager, who acts as an agent for the building owner, and the vendor. For example, there can be a clause in the landscape service agreement that the blade on mowers be raised to a certain level to allow longer grass, which makes it more drought-resistant. The grass height can occasionally be measured to ensure that the vendor is in compliance with the agreed-upon mower level per the service agreement. For supplies, the vendor service agreement can have a clause that only allows the property manager to select office products from a sustainable item list. This may include recycled paper and compostable cups. It’s important that there is someone on the property management team dedicated to regularly reviewing and enforcing the terms of these service agreements to ensure compliance with sustainability standards.

Considering the increased demand from investors and the market for sustainable building initiatives, there may be new business opportunities for vendors by offering supplies and services that are more sustainable. The creation of programs to address customer demands for sustainable services and products can help vendors gain a competitive edge, while vendors not willing to offer more sustainable services and products stand to lose business. However, it may cost vendors more to offer these sustainable materials and methods. Additionally, since some vendors may not be willing to offer these services, the owner/manager may be left with higher costs and/or fewer vendors to select from, which may impact cost or timeliness of deliveries. One way to address these barriers is for the property manager to negotiate a long-term contract based on collaboration to help counteract any higher costs and timeliness issues. By working with property personnel, vendors can collaborate on how to embed more sustainable practices into business operations through economies of scale and an agreed-upon timeline. This can also help align values and beliefs and lay a foundation for a long-term working partnership.

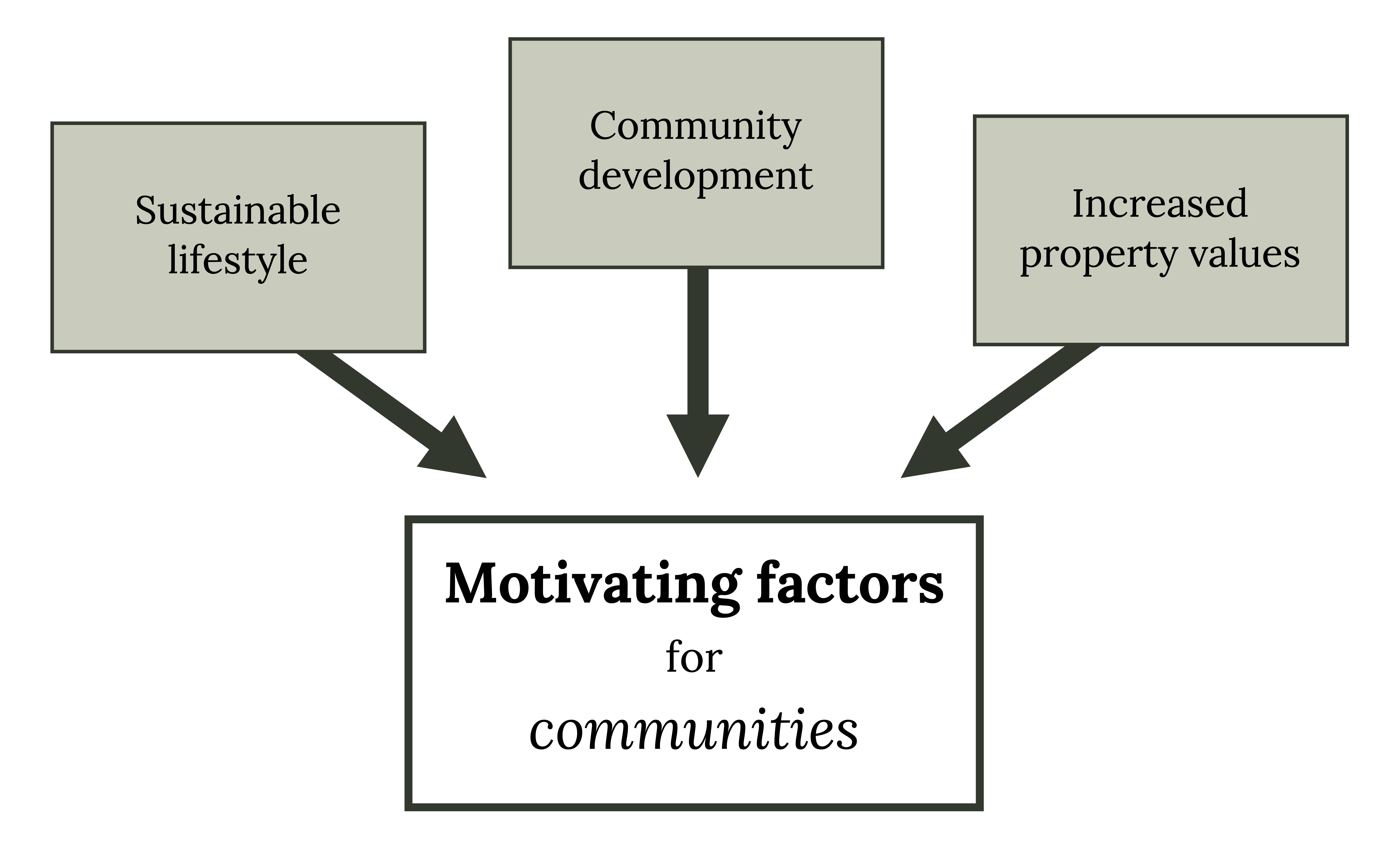

3.6 Communities

Wider community members are motivated to engage with sustainable property management principles for various reasons. Figure 3.7 lays out some common reasons for community engagement.

A sustainable lifestyle is increasingly becoming important to people, especially younger generations. Not only does this include ecologically sustainable practices such as recycling, minimizing single use plastics, and shopping local; it also focuses on economic opportunity through ethical sourcing, holding corporations accountable for their actions by boycotting or quitting from companies that appear irresponsible, and saving money by driving less, shopping from thrift stores, and minimizing hyper-consumerism. Engaging community members who find a sustainable lifestyle important can further sustainability efforts at the property and wider community as they can provide innovative ideas and extra support to get others on board with sustainability efforts. The wider community is also motivated to engage with sustainable property practices because they see that it can help with community development. For example, they may get involved to help the property set up farmers’ markets, a community garden, community yoga, service projects, a running club, a community compost bin, and green spaces, which help enhance the quality of the community. They can also educate and enlist the support of the community for initiatives that the community may at first consider negative externalities, such as installation of solar panels that will create a glare for surrounding properties. These collaborations among various community members can help the community and property thrive economically, socially, and environmentally by potentially increasing property values, building social relationships, and mitigating negative ecological externalities of the built environment.

There may be barriers to engagement by the community. For example, a composting area may produce an offensive smell, which the community may consider a negative externality. Another example is neighbors who oppose a farmers’ market because it causes nonresidents to park in their parking spaces when visiting the farmers’ market. When barriers like these arise, it is important to look for compromises and joint solutions that meet the needs of different stakeholders, but without disrespecting their right to opinions about the built environment. In the case of the farmers’ market example, the property manager could agree to somehow police parking violations as part of their programing efforts, although it should be noted that there is operational time and cost associated with this solution.

3.7 Conclusion

This chapter outlined various motivations for implementing sustainable property management practices. As can be seen, collaboration among various stakeholders is essential for a successful sustainable property management program at the property. Collaboration occurs through mutual respect and understanding of motivations while working toward compromises and joint solutions. This type of collaboration cultivates relationships among stakeholders and the desire to be good corporate and community citizens.

Discussion Questions

- What other factors may motivate key stakeholders in adopting a sustainable property management plan? And why is it a motivating factor for that particular stakeholder?

- As a building occupant, what sustainability features, if any, are important to you?

- Do you think sustainable property management operations will become a requirement in the future? Why or why not?

- What is your key takeaway from this chapter? In which section did you find it?

Activities

- Watch the following video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TWOVY1Q_otA. After watching the video, in one paragraph discuss how Bob Willard’s presentation can be applied to the property management field.

- Use the link below to access the Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency:

https://www.dsireusa.org/- Enter your zip code on the homepage to find incentives for renewables and efficiency in your area

- From the list provided, choose an incentive and answer the following:

- Name of the incentive

- State/Territory of the incentive

- Category of the incentive

- Policy/Incentive Type

- When it was created

- When it was last updated

- The goal of the incentive

Figure References

Figure 3.1: Key stakeholders in sustainable property management operations. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.2: Common motivating factors for building owners. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.3: Common motivating factors for property management companies. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.4: Common motivating factors for tenants. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.5: Real-time building energy monitoring example. Grand Canyon National Park. (2013). Lobby video display [photograph]. https://flic.kr/p/dMHdJq. CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.6: Common motivating factors for vendors. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.7: Common motivating factors for communities. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Image Descriptions

Figure 3.2: Motivating factors for building owners: local laws and regulations, investor and market pressure, green building certifications and GRESB points, positive financial statement impacts, environmentally conscientious corporate agenda. Return to figure 3.2.

Figure 3.3: Motivating factors for property management companies: property management agreement requirement, performance evaluation expectations, positive leasing impacts, higher management fees. Return to figure 3.3.

An operating plan developed by the property management company, with collaboration from various stakeholders, that outlines sustainability initiatives to be undertaken at the property and how these initiatives align with property ownership goals

Entity that holds title to the property

Entity that manages the operations and maintenance of the property

A contract between the building owner and property management company outlining the responsibilities of the property management company

Entity that occupies the property leased from a landlord

Programs to help tenants learn about ways to incorporate sustainable property management practices on a regular basis

The energy used by products that are plugged into an outlet

Contractors and suppliers that provide services and supplies to the property

Community members not directly involved with building operations

Excessive consumption of goods