1 Introduction to Sustainable Property Management

Chapter Contents

1.1 Introduction

1.2 What is Sustainable Property Management?

1.3 Why Sustainable Property Management Matters

1.4 Evolution of Sustainable Property Management

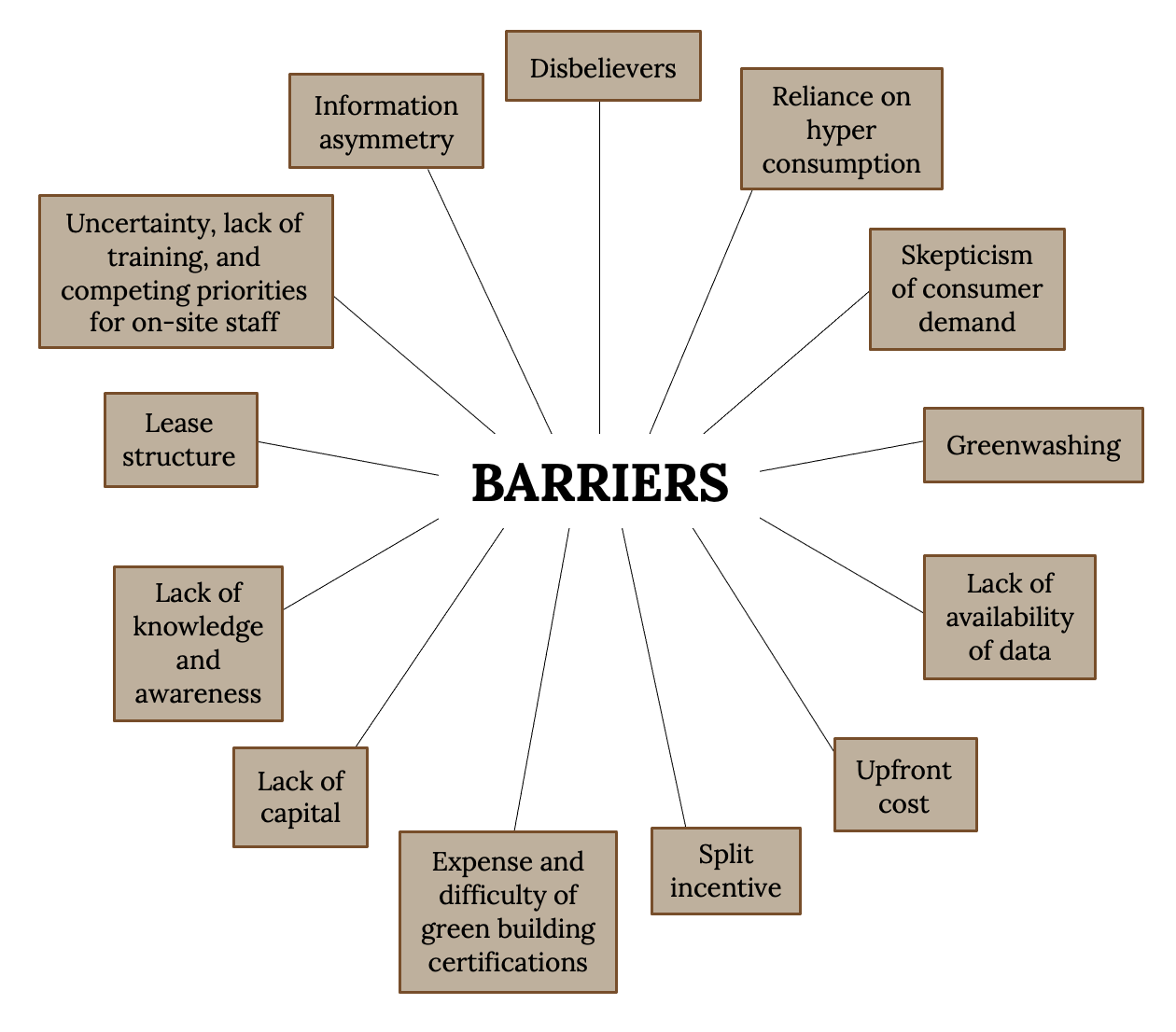

1.5 Barriers to Sustainable Property Management

1.6 Conclusion

Learning Objectives

- Explain the building lifecycle

- Define sustainable property management

- Identify the three spheres of sustainability

- Understand the role of real estate in sustainability

- Explain why sustainable property management matters

- Identify what’s driving sustainable property management

- Describe the main barriers of sustainable property management

1.1 Introduction

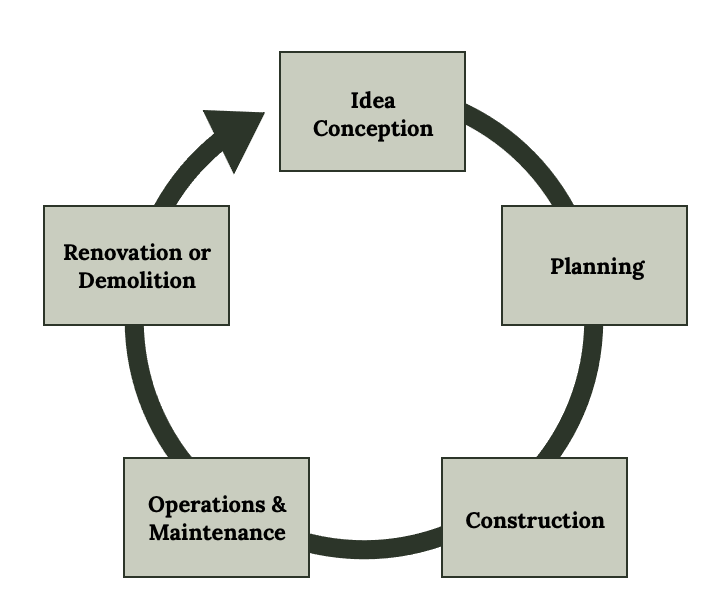

Every building has a lifecycle that begins with the initial idea conception and continues all the way through to the building’s eventual demolition, as illustrated in figure 1.1. Green building initiatives, defined as actions undertaken to minimize the environmental impact of a building, can be implemented throughout the building lifecycle. This textbook focuses on the operations and maintenance phase of the building lifecycle although there are certainly benefits in greening the building lifecycle in its entirety. Property management takes place during the operations and maintenance building lifecycle phase and includes functions such as human resources, relationship management, finance, accounting, maintenance, repairs, risk management, marketing, and leasing. So while greening property management functions cannot impact certain important aspects of the building, such as how the building is sited or built, it can impact the operations and maintenance phase, the longest phase within the building lifecycle.

The aim of green property management is to mitigate negative ecological effects associated with the building during the operations and maintenance building lifecycle phase. However, sustainable property management is a concept that incorporates the human and social elements of managing green buildings as well as the green buildings themselves. The term sustainable, which appears in the title of this book, is used specifically to convey the explicit relationships between humans, the ecological environment, and a building. In many cases, the building is seen as separate from the human, but humans create and manage buildings so they are an integral part when learning about sustainable property management.

This chapter introduces the term sustainability, what it means, and how it applies to property management. The chapter also describes the evolution of sustainable property management and introduces why sustainable property management matters. Of course, sustainable property management has many potential benefits, but there are also downsides and barriers, which must be acknowledged in order to understand why sustainable property management is not more pervasive across the property management industry.

1.2 What is Sustainable Property Management?

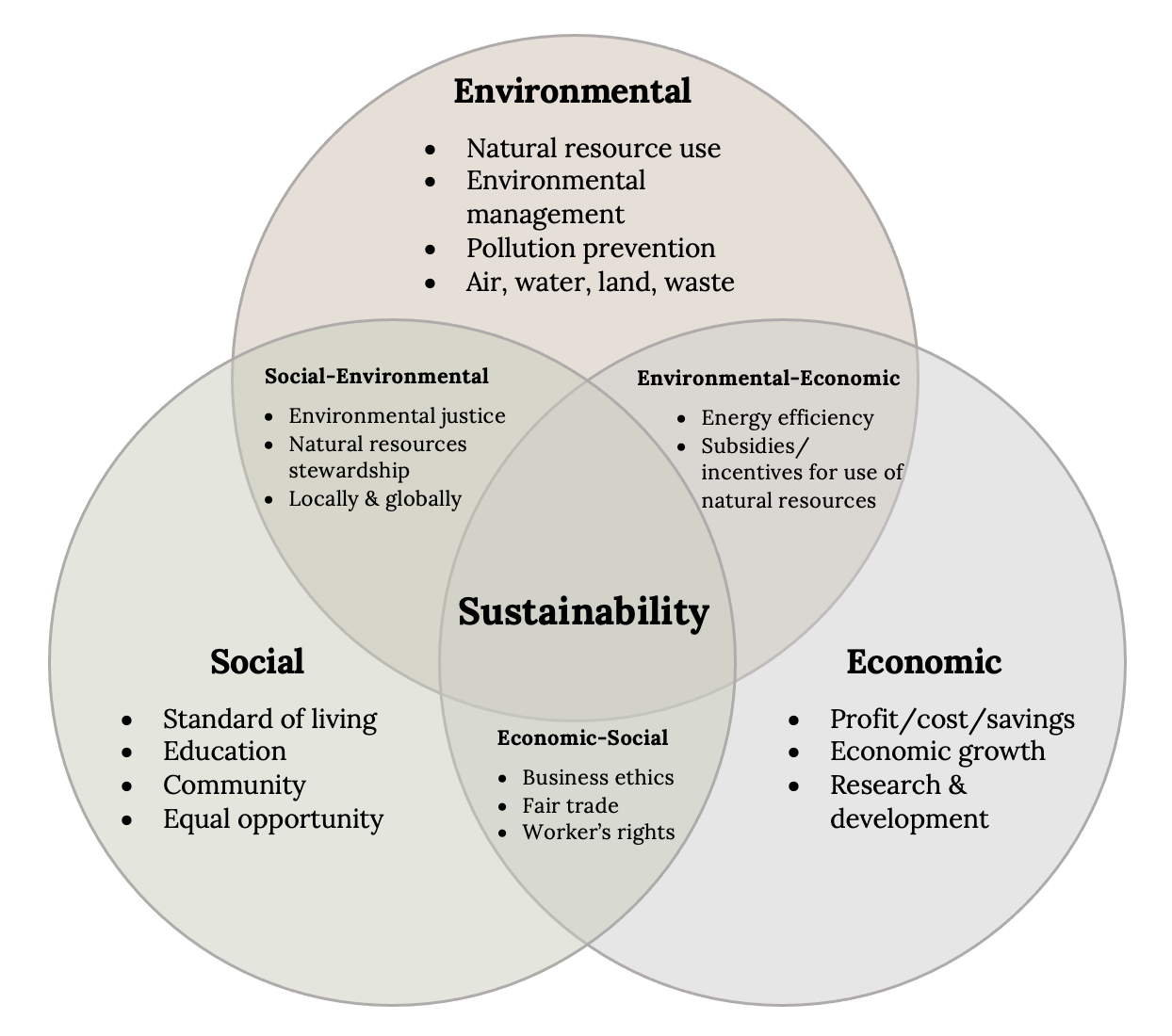

Sustainability, simply defined as the ability to meet current generation needs without compromising future generation needs, is on the rise across industries and the property management industry is no exception. Although sustainability, as used in the real estate context, is about preserving the environment, it is about more than that. In sustainable property management, sustainability encompasses three spheres—environmental, social, and economic (see fig. 1.2). Sustainable property management is implementing green building initiatives during the operations and maintenance phase of the building lifecycle, taking into account their environmental, social, and economic impacts with the goal of reconciling these three spheres in such a way that a balance is achieved between economic development and protection of environmental and social resources.

Example: Balancing the Three Spheres of Sustainability in Property Management

One example of balancing the three spheres of sustainability might be when a management company must decide what sort of cleaning practices to employ in a building. Cleaning products that are environmentally friendly might be more desirable for the Earth and human health, but they might also be more expensive, in which case cost must be balanced against the impact on the environment and the impact on human health. Another example is to suppose a new regulation requires all new carpet installations to be low-VOC (Volatile Organic Compounds) as these chemicals used in the carpet manufacturing process can pose a variety of health risks that negatively affect people and the Earth. For this reason, low-VOC carpeting is healthier to humans than high-VOC carpeting. Because of the regulation, Because of the regulation, tenants at all income levels have access to healthier indoor air quality. However, the carpet is expensive and, as a result, owners/managers may either (a) leave existing carpet in longer until it becomes overused and probably unhealthy, making tenants arguably worse off from a health perspective, or (b) pass the cost through to tenants, who are now financially worse off than they would have been in the absence of the new regulation. Note that there is no mechanism to force private sector owners/managers to lower the investment’s required rate of return to subsidize the new carpet. Do you support the new regulation? Something to think about in this situation is the possibility of implementing a comprehensive sustainable building plan that overall is able to create net financial savings and therefore a positive financial impact on the rate of return, while also addressing human and Earth health.

Property companies obtain various third-party independent certifications to illustrate commitment to sustainable property management, as illustrated in table 1.1.

| Professional Accreditations | ||

| Logo | Third-Party Green Building Accreditation | Organization that Developed Accreditation |

| LEED Accredited Professional (AP) for Operations and Maintenance (O+M) Certification | U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) | |

| LEED Green Associate Credential | U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) | |

| Building Certifications | ||

| Logo | Third-Party Green Building Certification | Organization that Developed Certification |

|

LEED Certification | U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) |

|

Certified Sustainable Property (CSP) | Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM) |

| ENERGY STAR® Building Certification | Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) | |

|

Parksmart Certification Standard for Existing Structures | Green Business Certification Inc. (GBCI) |

|

Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) In-Use | Building Research Establishment (BRE) |

|

Green Star—Performance | Green Building Council of Australia |

Table 1.1: A selection of global sustainable property management accreditations and certifications.

Arguably, the most widely used green building certification throughout the world is known as LEED—Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design. LEED certification for buildings was developed by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), a private non-profit organization founded in 1993, to provide certification opportunities throughout the building lifecycle. This is why there are multiple LEED certifications, including LEED for Building Design and Construction (LEED BD+C) and LEED for Operations and Maintenance (O+M) (U.S. Green Building Council, 2020). The categories associated with the LEED O+M certification include location and transportation, sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, indoor environmental quality, innovation, and regional priority. People can also achieve a LEED credential such as LEED Green Associate to demonstrate their overall knowledge in green building principles or LEED Accredited Professional (AP) to demonstrate advanced knowledge in green building principles in a specific LEED rating system such as LEED O+M.

The Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM) offers a Certified Sustainable Property (CSP) designation, which focuses exclusively on the operations and maintenance phase of a building. This certification addresses categories such as energy, water, health, recycling, and purchasing. The ENERGY STAR certification for buildings is offered through the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and, as the name implies, focuses strictly on the energy use of a building. Parksmart, a third-party certification that focuses on sustainable parking garages, offers a Parksmart Pioneer certification for existing parking structures that focuses on management, programs, and technology and structure design. Internationally, there are green building certifications such as the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) In-Use certification that originated in the United Kingdom and focuses on the operational phase of the building lifecycle. The BREEAM In-Use certification focuses on management, health and wellbeing, energy, transport, water, resources, resilience, land use and ecology, and pollution. Originating in Australia, the Green Star—Performance certification is available for the operational phase of a building and its categories include management, indoor environment quality, energy, transport, water, materials, land use and ecology, emissions, and innovation.

By no means is the green building management certifications list in table 1.1 complete, but it provides a sampling of some of the prominent certifications. The larger point here is that sustainable property management certification is happening on a comprehensive and global scale. However, it’s important to point out that just chasing a green building certification may not produce the desired sustainability results. This is because a green building certification is only as sustainable as its embodied concepts.

Section Videos

What is Corporate Sustainability?

[00:02:25] Network for Business Sustainability. https://youtu.be/ltBUjzuncQ4

What Is LEED?

[00:01:10] U.S. Green Building Council. https://youtu.be/tlVseOWToL4

Top 5 Reasons To Get ENERGY STAR Certification For Your Building

[00:03:19] ENERGY STAR. https://youtu.be/gwVkBcIjBho

Section Reference

U.S. Green Building Council. (2020). What is LEED? https://www.usgbc.org/help/what-leed

1.3 Why Sustainable Property Management Matters

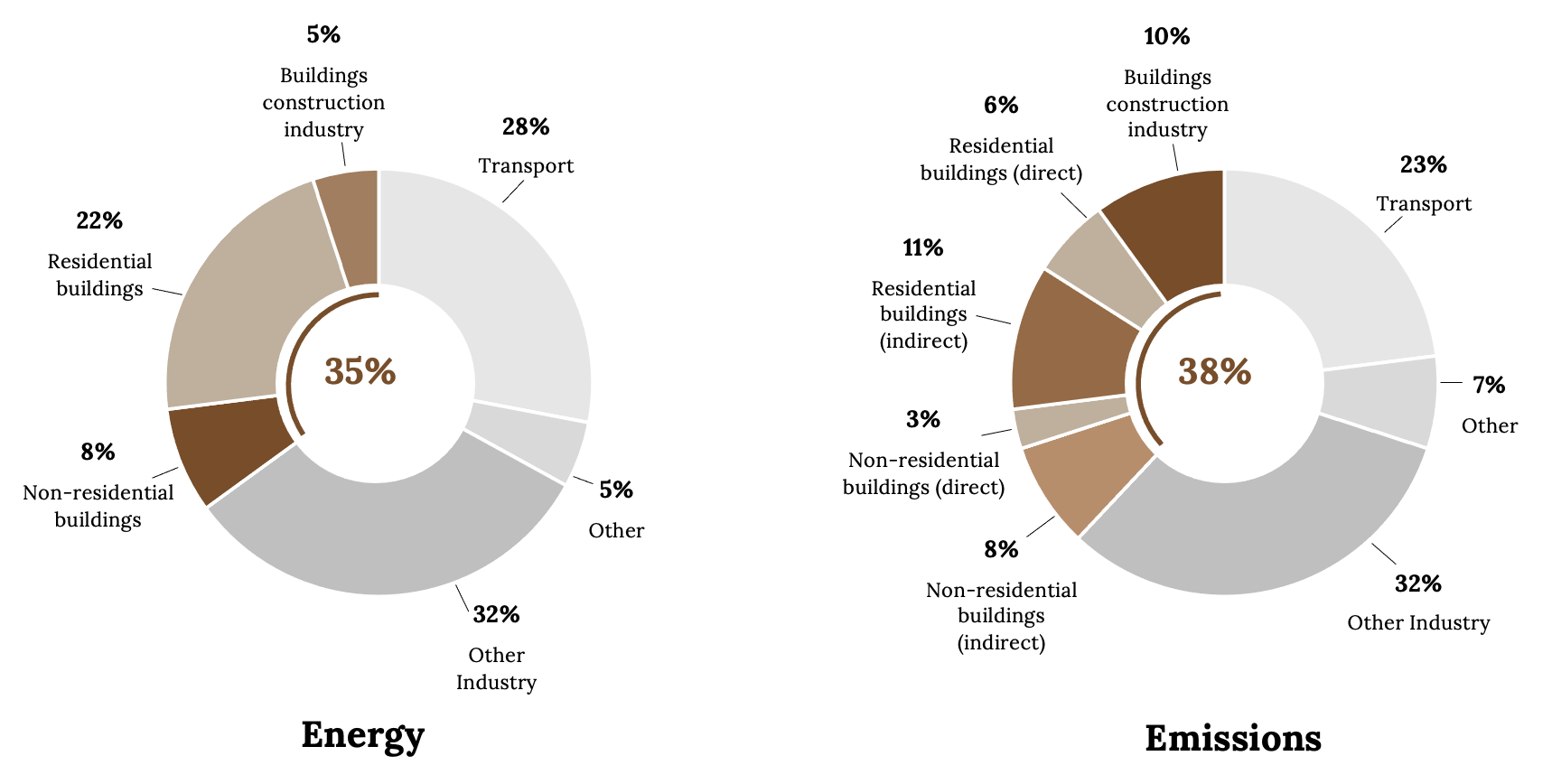

Sustainable property management matters because building operation activities contribute to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. As of 2019, building operations represented 28 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions related to energy, representing the highest level ever recorded (United Nations Environment Programme, 2020). As seen in figure 1.3, energy and carbon dioxide emissions related to energy in residential buildings and non-residential buildings account for the largest single industry user of energy and emitter of carbon dioxide. This matters because carbon dioxide emissions, a type of greenhouse gas emissions, trap heat causing the Earth to become warmer (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2021).

Climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions has a number of negative effects on the Earth: shrinking water supplies, increasingly severe weather incidents, disruptions in food supply, and geographical changes to the Earth, to name just a few (Sciencing, 2021). These environmental changes not only negatively affect the environment, they also negatively affect society and the economy. As water and food are essential to human survival, a shrinking water supply and shift in food supply negatively affect human health and can increase the cost of procuring these essential supplies. Also, severe weather and rising tides that are changing the geography of the Earth affect the safety and well-being of society and incur significant costs to repair buildings and infrastructure.

Sustainable property management can reduce negative environmental externalities, which in turn can foster benefits in the social and economic spheres as well. As the three spheres of sustainability overlap, sustainable property management illustrates the concept of interdependence. For example, sustainable property management can foster a decrease in carbon dioxide emissions while also lowering energy and water costs and providing healthier indoor environments for a building’s occupants. So while sustainable property management’s focus is primarily on ecological sustainability drivers, the economic and social spheres cannot be ignored as these spheres are interrelated and dependent on each other.

Section Video

What Is Greenhouse Gas?

[00:01:16] TestTube 101. https://youtu.be/nI1iWrxO6Y8

Section References

Cairoli, Sarah. (2023, February 10). Consequences of carbon emissions for humans. sciencing.com. https://sciencing.com/consequences-of-carbon-emissions-for-humans-12730960.html

United Nations Environment Programme. (2020). 2020 Global status report for buildings and construction: Towards a zero-emission, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector. https://globalabc.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/2020 Buildings GSR_FULL REPORT.pdf

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2021). Sources of greenhouse gas emissions. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

1.4 Evolution of Sustainable Property Management

The idea of sustainable buildings was born out of the environmental movements of the 1970s and 1980s. In response to these movements, the United Nations established the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1983. In 1987, the Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future (also known as the Brundtland Report) was published by the United Nations and contained a call to action for sustainable development in the built environment.

The growth of third-party green building certifications can be used as a proxy to gauge the increased level of stakeholder demand for sustainable buildings over time. Table 1.2 shows the year various green building certifications were introduced. This table only includes green building certifications that offer an option to certify existing buildings. The first green building certification system was introduced in 1990 by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) out of the United Kingdom. ENERGY STAR and LEED certifications, out of the United States, were also introduced prior to the turn of the century. Since 2000, many more green building certifications have been created as well as updates made to existing certifications. Although there is no global reference list, over six hundred tools that assess sustainability relating to at least one sphere have been identified worldwide, including thirty-eight green building labels (McCreadie, 2004; Reed et al., 2009).

| Year | Label | Country |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | BREEAM | United Kingdom |

| 1993 | ENERGY STAR for Buildings | United States |

| 1995 | ENERGY STAR for Homes | United States |

| 1998 | LEED for Building Design and Construction | United States |

| 2001 | CASBEE | Japan |

| 2003 | Green Star | Australia |

| 2005 | LEED for Existing Buildings | United States |

| 2009 | BREEAM In-Use | United Kingdom |

| 2009 | DGNB System | Germany |

| 2009 | BOMA 360 | United States |

| 2013 | Green Star-Performance | Australia |

| 2015 | IREM CSP | United States |

Table 1.2: Introduction of green building certifications that offer certification for existing buildings, by country and year of introduction.

When these certifications were first introduced, many of them focused on the building design and construction portion of the building lifecycle, with little or no thought given to the operations and maintenance of existing buildings. For example, while BREEAM was launched in 1990, the BREEAM In-Use certification for operations and maintenance was not created until 2009 (BREEAM, 2021). Additionally, LEED for building design and construction was introduced in 1998, but LEED for existing building operations and maintenance was not launched until the middle of the 2000s. Two notable exceptions to this focus on building design and construction during certification creation is ENERGY STAR for Buildings and ENERGY STAR for Homes, which focus strictly on the operations phase of the building lifecycle.

More recently, stakeholder demand has been a driver for increased Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria reporting, which is a “set of standards for a company’s operations that socially conscious investors use to screen potential investments” (Chen, 2021). The Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark (GRESB) assessment framework, founded in 2009, is used as an ESG benchmark for real estate assets. As of 2021, 117,000 real estate assets across 1,520 property companies, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT), funds, and developers participated in the GRESB Real Estate Assessment, representing $5.7 trillion of assets under management (“The GRESB ESG benchmarks,” 2021). (Chapter 2 provides further details on the GRESB Framework.) Companies can earn points for green building certifications as part of this benchmark, but ESG reporting embodies sustainability on a more holistic level, whereas green building certifications primarily address the environmental sphere of sustainability.

Example: Driver for Sustainable Building Demand

The Federal National Mortgage Association, also known as Fannie Mae, offers an economic benefit to multifamily properties with a recognized green building certification through preferential loan pricing.

Further details can be found at: https://multifamily.fanniemae.com/financing-options/specialty-financing/green-financing/green-financing-loans/green-building-certifications

Another factor driving the evolution of sustainable property management is technology. Smart buildings, made possible by advances in technology, have emerged with the goal of increasing building efficiencies as well as lowering operational costs. In smart buildings, building systems such as HVAC, lighting, and security are linked with real-time sensors that provide information to enable building automation and provide a comfortable atmosphere for building occupants. This also helps to better track operational data such as energy and water use.

Example: Evolution of Sustainable Property Management Driven By Technology

Lighting significantly influences the energy use of a building. Prior to some advances in technology, a method to encourage energy efficiency was to place a “Please turn off lights when not in use” label over the light switch to encourage occupants to turn off the lights when leaving the building space.

Although you may still see some of these on light switches, technology advanced and motion sensors were then installed within some building spaces to automatically turn the lights off when the sensor detected no more movement within that particular building space.

Technology then took another leap and smart light bulbs were invented. This enabled occupants to set timers or manually turn off the lights in a building space using a smartphone. So now, lights can be automated from virtually anywhere in the world through a smartphone.

While technology continues to advance, the conservation and cost savings concepts remain the same as proven by this example.

Sustainable property management has evolved as a strategy to address environmental concerns affecting the Earth and people, while also focusing on profit by considering net operating income (NOI) through either reducing operating expenses and/or increasing revenues. Profit is still a main focus for companies, but the environment and people are also increasingly a focus. Furthermore, the increased demand for sustainability from various stakeholders such as investors and building occupants is driving the property management industry to respond and increasingly incorporate sustainable building practices into the operations and maintenance of the real estate asset.

Section Video

The Greening Of The Real Estate Industry

[00:04:14] Urban Land Institute. https://youtu.be/EyS0hfl1miM

Section References

BREEAM. (2021). BREEAM in-use. https://www.breeam.com/discover/technical-standards/breeam-in-use/

Chen, J. (2022). What Is Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Investing? Investopedia.com. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/environmental-social-and-governance-esg-criteria.asp

GRESB. (2021, August 30). The GRESB ESG benchmarks expand in 2021 to cover $6.4 trillion of assets under management despite global challenges from Covid-19. https://www.gresb.com/nl-en/insights/the-gresb-esg-benchmarks-expand-in-2021-to-cover-6-4-trillion-of-assets-under-management-despite-global-challenges-from-covid-19/

McCreadie, M. (2004). BRE subcontract: Assessment of sustainability tools. (BRE report No. 15961) https://download.sue-mot.org/envtooleval.pdf

Reed, R., Bilos, A., Wilkinson, S., & Schulte, K. W. (2009). International comparison of sustainable rating tools. Journal of sustainable real estate, 1(1), 1–22.

UN. Secretary-General; World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: our common future https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/139811

1.5 Barriers to Sustainable Property Management

The real estate industry has certainly made significant progress in adopting sustainable practices, but a number of barriers still stand in the way of further progress. This can be seen in figure 1.7. First is climate change denial. Despite the fact that the U.S. EPA acknowledges that human activities cause climate change, many people remain disbelievers (U.S. EPA, 2021). Because of this disbelief, sustainable property management practices may seem somewhat irrelevant to these disbelievers, as they do not believe humans are contributing to climate change on Earth. Furthermore, even if people do believe in human-based climate change, there is a strong reliance on hyperconsumption to sustain a modern convenient lifestyle in developed and developing countries.

Building owners and property managers may also be skeptical of consumer demand for these types of features. So this may make sustainable property management a non-priority in their business development plan and thus in their corporate image. Or alternatively, they may be greenwashing their company, which is a marketing tactic that portrays a property to be greener than it actually is. This can increase a company’s corporate social image and the company can potentially acquire more business because of this image.

Some may also view the upfront cost to implement sustainable property management initiatives as too high a barrier even if there may be operating costs savings, such as reduced energy use. This is especially true if a new building is being built and the building owner does not intend to hold onto the real estate asset for a long period of time. This relates to the payback period of a capital outlay for a sustainable building initiative.

Example: Payback Period Barrier

If the building owner plans to hold the building for five years, and the payback period for a more energy efficient heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system takes seven years to payback on the investment, the payback of the additional capital outlay for the more efficient HVAC system will not likely occur due to the payback occurring after the building is sold by that owner. This rings even truer for the merchant builders who sell their buildings immediately upon completion. An additional consideration is the lease structure, which differs among property types, that can further impede adoption of sustainable property management practices. Therefore, the upfront cost to adopt some sustainable building initiatives poses a barrier.

Even if an owner plans to hold onto a building for the long-term, a split incentive issue can arise in which either the landlord or tenant is not financially incentivized to invest in sustainable initiatives. For example, if the tenant pays their own utility bills, the property owner is not financially incentivized to provide energy efficient appliances and fixtures because the cost savings accrue to the tenant. The exception to this is if the cost savings that the tenants receive from these ecologically sustainable investments are fully capitalized into the rental rate. On the other hand, if the landlord pays for utilities, the tenant is not financially incentivized to save on utilities so they may keep their unit extra warm during the winter season and extra cool in the summer season.

Property owners and managers commonly find green building certifications too hard and too expensive to obtain. This is especially true for companies that lack the size or resources to fulfill the requirements of green building certifications. Additionally, there may be a lack of capital for implementation of certain sustainable building management initiatives. These barriers are evidenced by looking at the most prevalent green building certification system in the US, LEED. As of the end of 2015, there were only 34,000 LEED building certifications compared to the total U.S. building stock of 5,500,000, representing a certification rate of 0.7 percent (Yudelson, 2016). Yudelson (2016) also puts forward the barriers of bureaucracy, overblown benefit claims, and a narrow focus on obtaining points versus material results related to LEED certification.

Lack of knowledge and awareness as well as lack of availability of data also create barriers to sustainable property management practices. For example, the decision-makers may lack the understanding of how the initial upfront costs may generate savings down the line when implementing a sustainable property management initiative. Even if this is understood and the economic numbers make sense, the unwillingness of on-site staff to embrace these initiatives due to uncertainty, lack of training, or competing priorities can prevent these initiatives from coming to full fruition. Additionally, information asymmetry can occur because sustainable property management can mean very different things to different people. This can cause lack of investment in sustainable property management. Decision-makers may instead invest in initiatives that have a clearer quantitative benefit.

Section References

US EPA. (2021). Climate change indicators in the United States. https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators

Yudelson, J. (2016). Reinventing green building: Why certification systems aren’t working and what we can do about it. New Society Publishers.

1.6 Conclusion

Sustainable property management utilizes sustainable building initiatives during the operations and maintenance phase of the building lifecycle, taking into account the environmental, social, and economic impacts of these building initiatives. This is becoming more commonplace in response to demand for sustainability from multiple stakeholders. Sustainable property management is important because it can positively impact all three spheres of sustainability. Furthermore, as technology is advancing it is providing more opportunities for data benchmarking and reporting, which allows for more quantifiable data on the progress of sustainable building management initiatives and their impacts on the environmental, social, and economic realms. It is important to remember that sustainable building practices are as much of a human science as well as a building science because humans, not the building itself, create and manage buildings. As the evolution of sustainable property management marches on, there remain barriers that must be addressed in order to further increase implementation of sustainable building practices.

Discussion Questions

- How would you define sustainable property management?

- What are the three spheres of sustainability? Provide an example of each sphere as it relates to sustainable property management.

- Try to identify one or two sustainable property management practices at work in the buildings you occupy. What are they and do you think they have been successful?

- Why do you think companies focus mostly on the economic sphere and not always the social and environmental spheres when considering sustainable property management initiatives?

- What do you think would be effective incentives for companies to focus on for social and environmental spheres and not just the economic sphere of sustainability?

- How might you try and incorporate sustainable property management into your business development plan?

- Would you consider sustainable property management practices important to you? Why or why not?

- What is your key takeaway from this chapter? In which section did you find it?

Activities

- Go to https://www.nmhc.org/research-insight/the-nmhc-50/top-50-lists/2021-top-manager-list/ and choose three property management companies from this list. Review each of the three companies’ websites and report on the following:

- Are each of the three companies addressing sustainability on their websites?

- If so, which spheres of sustainability are they addressing and what examples do they provide related to each sphere?

- What do you think they may be missing the mark on in regards to sustainability?

- Were you surprised by your findings? Why or why not?

- Research the pros and cons of green building certifications and report your findings on one page.

Figure References

Figure 1.1: Building lifecycle. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.2: The three spheres of sustainability. Kindred Grey. (2023). Adapted from Investigation of the Philosophy Practised in Green and Lean Manufacturing Management, by A. Aminuddin and M. Nawawi, 2013, International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management, 4(1) (DOI:10.4018/jcrmm.2013010101). Copyright 2013 by the International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management. Adapted under fair use.

Figure 1.3: Global share of buildings and construction final energy and emissions (2019). Kindred Grey. (2023). Data from United Nations Environment Programme 2020 Report. CC BY 4.0. https://globalabc.org/resources/publications/2020-global-status-report-buildings-and-construction).

Figure 1.4: Original energy efficiency attempt. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.5: Motion sensors. Z22. (2014). Motion sensors [photograph with adjusted color]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Light_switch_with_passive_infrared_sensor.jpg. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 1.6: Smart light bulbs. Jefferson William. (2019). Smart light bulbs [photograph]. Public domain. https://flic.kr/p/2hKtK3k

Figure 1.7: Sustainable property management barriers. Kindred Grey. (2023). CC BY 4.0.

Image Descriptions

Figure 1.2: 3 overlapping circles (Venn Diagram). Circle 1: Environmental – natural resource use, environmental management, pollution prevention, air/water/land waste. Circle 2: Economic – profit/cost/savings, economic growth, research and development. Circle 3: Social – standard of living, education, community, equal opportunity. Circle 1&2 overlap: Environmental-Economic – energy efficiency, subsidies/incentives for use of natural resources. Circle 2&3 overlap: Economic-Social – business ethics, fair trade, worker’s rights. Circle 3&1 overlap: Social-Environmental – environmental justice, natural resources stewardship, locally & globally. All 3 circles overlap: Sustainability. Return to figure 1.2.

Figure 1.3: 2 pie charts. Left: Energy. 8% Non-residential buildings, 22% residential buildings, 5% buildings construction industry, 28% transport, 5% other, 32% other industry. Right: Emissions. 8% Non-residential buildings (indirect), 3% Non-residential buildings (direct), 11% residential buildings (indirect), 6% residential buildings (direct), 10% buildings construction industry, 23% transport, 7% other, 32% other industry. Return to figure 1.3.

Figure 1.7: Barriers: Disbelievers, reliance on hyper consumption, skepticism of consumer demand, greenwashing, lack of availability of data, upfront cost, split incentive, expense and difficulty of green building certifications, lack of capital, lack of knowledge and awareness, lease structure, uncertainty/lack of training/competing priorities for on-site staff, information asymmetry. Return to figure 1.7.

Actions undertaken to minimize the environmental impact of a building

The life of a building from idea conception to renovation or demolition

Management of a property during the operations and maintenance phase of the building lifecycle

The ability to meet current generation needs without compromising future generation needs

Implementation of green building initiatives during the operations and maintenance phase of the building lifecycle, taking into account their environmental, social, and economic impacts

A third-party green building certification

Green building certifications for the operations and maintenance phase of the building lifecycle such as LEED O+M, IREM CSP, BREEAM In-Use, and ENERGY STAR Certification

Gases that trap heat in the Earth's atmosphere

Human-made environments where people live, work, and play

A set of standards used by socially conscious investors to evaluate investments

An assessment framework used as an ESG benchmark for real estate assets

Entities that own or finance income-producing real estate through capital from many investors

The disclosure of environmental, social, and governance data

Buildings with building systems such as HVAC, lighting, and security that are linked with real-time sensors that provide information to enable building automation with the goal of increasing building efficiencies as well as lowering operational costs

Total Operating Revenue minus Total Operating Expenses

A marketing tactic that portrays a property to be greener than it actually is

The time period it takes to recover the initial capital outlay of an investment through revenue or cost savings

Builders that build buildings for resale in the near future

The initial capital outlay for a product or service