1.3 Data Collection and Observational Studies

Does aspirin reduce the risk of heart attacks? Is one brand of fertilizer more effective at growing roses than another? Is fatigue as dangerous to a driver as the influence of alcohol? When we are interested in the effect one variable may have on another, we call the first variable the explanatory variable and the second the response variable. Questions like these are answered using studies and experiments. Proper study design ensures the production of reliable, accurate data.

Data Collection Methods

There are many ways data is commonly collected, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. Some ways data may be collected are:

The latter two options are more commonly accepted, but we will briefly describe the former first.

Anecdotal Evidence

Consider the following statements seemingly based on data:

- I met two students who took more than seven years to graduate from Duke, so it must take longer to graduate at Duke than at many other colleges.

- A man on the news had an adverse reaction to a vaccine, so it must be dangerous.

- My friend’s dad had a heart attack and died after they gave him a new heart disease drug, so the drug must not work.

Though each conclusion is technically based on data, there are two problems. First, the data in each example only represent one or two cases. Second, and more importantly, it is unclear whether these cases are actually representative of the population. Data collected in this haphazard fashion is called anecdotal evidence. While such evidence may be true and verifiable, be careful of data collected in this way since it may only represent extraordinary or unusual cases. Often, we are more likely to recall anecdotal evidence based on its striking characteristics. For instance, in Case #1 above, we are more likely to remember the two people we met who took seven years to graduate than the six others who graduated in four years. Instead of looking at the most unusual cases, we should examine a sample of many cases that represent the population.

Observational Studies

Researchers perform an observational study when they collect data in a way that does not directly interfere with how the data arises. For instance, researchers may collect information via a questionnaire or survey, review medical or company records, or follow a large group of similar individuals to form hypotheses about why certain diseases develop. In each of these situations, researchers merely observe the data that occurs. In general, observational studies can provide evidence of naturally occurring associations between variables, but they cannot by themselves show a causal connection. Why not? Consider the following example.

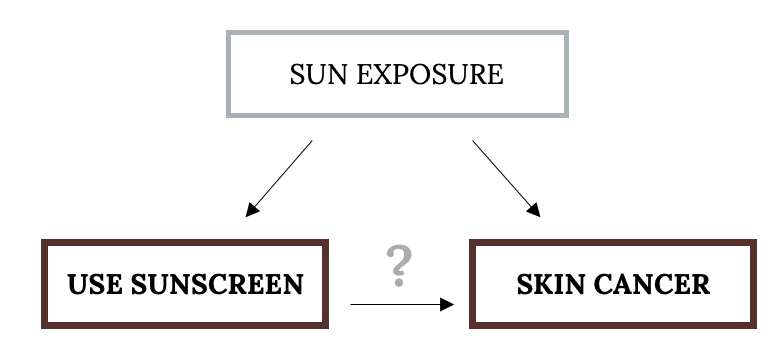

Suppose an observational study tracking sunscreen use and skin cancer found that the more sunscreen someone used, the more likely the person was to have skin cancer. Does this mean sunscreen causes skin cancer? Some previous research tells us that using sunscreen actually reduces skin cancer risk, so maybe there is another variable that can explain this hypothetical association between sunscreen usage and skin cancer. One important piece of information that is absent may be sun exposure.

Exposure to the sun is unaccounted for in this simple investigation, even though it stands to reason if someone is out in the sun all day, she is more likely to use sunscreen but also more likely to get skin cancer. Sun exposure here is an example of what we might call a confounding variable. Also known as a lurking or conditional variable, this is a variable that was not accounted for and may actually be important. Confounding variables can cause many misleading, counterintuitive, or even humorous (spurious) correlations.

Observational studies come in two forms: prospective and retrospective. A prospective study identifies individuals and collects information as events unfold. For instance, medical researchers may identify and follow a group of patients over many years to assess the possible influences of behavior on cancer risk. One example of such a study is the Nurses’ Health Study, started in 1976 and expanded in 1989. This prospective study recruits registered nurses and then collects data from them using questionnaires. Retrospective studies collect data after events have taken place (e.g., researchers reviewing past events in medical records). Some datasets may contain both prospectively and retrospectively collected variables.

There are other classifications of observational studies you may encounter, especially in life science and medical contexts. A cohort study follows a group of many similar individuals over time, often producing longitudinal data. A cross-sectional study indicates data collection on a population at one point in time (often prospective). A case-control study compares a group that has a certain characteristic to a group that does not, often taking the form of a retrospective study for rare conditions.

Example

A researcher is studying the relationship between time spent studying in medical school and depression rates among students. The researcher looks at graduated students’ medical records to determine if they have ever seen a psychologist. He also sends out a questionnaire to the same students to ask how much time they spent studying in college. What type of study is this?

Solution

This is both a prospective and retrospective observational study. Sending out a questionnaire indicates a prospective study, while reviewing past medical records indicates a retrospective study.

Your Turn!

Additional Resources

Figure References

Figure 1.3: Jason Leung (2018). Selective focus photo of red peonies. Unsplash license. https://unsplash.com/photos/nonlZlChSZQ

Figure 1.4: Kindred Grey (2020). Association between sunscreen and skin cancer. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 1.3: Close up photo of a peony bush at sunrise.

Figure 1.4: Three boxes form a triangle. The top box reads ‘sun exposure’ and has arrows pointing to two boxes. The bottom left box reads ‘use sunscreen’ and the bottom right reads ‘skin cancer’. There is an arrow with a question mark pointing from the bottom left box to the bottom right one.

The independent variable in an experiment; the value controlled by researchers

The dependent variable in an experiment; the value that is measured for change at the end of an experiment

Actual values (numbers or words) that are collected from the variables of interest

Evidence that is based on personal testimony and collected informally

Data collection where no variables are manipulated

Data collection where variables are manipulated in a controlled setting

A relationship between variables

A variable that has an effect on a study even though it is neither an explanatory variable nor a response variable

Collecting information as events unfold

Collecting or using data after events have taken place

Longitudinal study where a group of people (typically sharing a common factor) are studied and data is collected for a purpose

Collecting data multiple times on the same individuals over a period of time, usually in fixed increments

Data collection on a population at one point in time (often prospective)

A study that compares a group that has a certain characteristic to a group that does not, often a retrospective study for rare conditions