Chapter 7 Entrepreneurship and Small Business Development

Learning Objectives

- Define entrepreneur and describe what it means to be entrepreneurial.

- Identify common roles or activities needed to start your own business.

- Explain the conditions of when entrepreneurship takes place.

- Describe the different kinds of funding approaches to starting a company.

- Identify different parts of an entrepreneurial ecosystem that entrepreneurs can leverage when starting up.

- Explain the assumptions that can cause some startups to fail.

What is Entrepreneurship? What does Entrepreneurial Mean?

Entrepreneurship as a social science is the study of how people turn an idea into reality to create a new social agreement or institution (most often a new business). Social agreements are taken for granted ways of organizing so that the social world works and usually for the benefit or safety of a greater societal whole.

Entrepreneurs try to change the status quo or existing social agreements to new ways of doing things that are beneficial for a particular group of people. This proactive process of overcoming constraints to create value in new ways is what is meant by the adjective “entrepreneurial“. An entrepreneurial spirit refers to someone that challenges the status quo and tries new ways to solve a problem. It can also refer to someone who is able to take limited resources—a constraint—and create something valuable. Historically speaking, the term entrepreneur was used to describe individuals who take on the financial risk that something might not work out believing they can take action that will generate a profit. Economists have further specified that entrepreneurs act under conditions of uncertainty rather than risk. Risk is something you can guess the results of, a kind of probability. Uncertainty is a kind of knowledge problem that doesn’t have probabilities and can’t really be guessed.

To illustrate the concept of uncertainty versus risk imagine that this cloud encompasses everything that you need to know to successfully run the business you want to start. Now imagine within the cloud there is a smaller circle that represents everything you are aware of in relation to starting the business, and finally inside of that circle is an even smaller circle about what you already know how to do to start the business. All that stuff that is outside your circle of knowledge that you are aware of is risk and all the other stuff that is outside your circle of awareness is uncertainty. It is the things that you don’t even know you should worry about. It also represents stuff you can’t know because it is dependent upon the future action of yourself and others like potential customers or competitors. As entrepreneurs take action and interact with others under these kinds of conditions they are able to reduce the uncertainty associated with a new venture.

The Nature of Entrepreneurship

If we look a little more closely at the definition of entrepreneurship, we can identify three characteristics of entrepreneurial activity:[1]

- Innovation. Entrepreneurship generally means offering a new product, applying a new technique or technology, opening a new market, or developing a new form of organization for the purpose of producing or enhancing a product.

- Running a business. A business, as we saw in Chapter 1 “The Foundations of Business,” combines resources to produce goods or services. Entrepreneurship means setting up a business to make a profit.

- Risk taking. The term risk means that the outcome of the entrepreneurial venture can’t be known. Entrepreneurs, therefore, are always working under a certain degree of uncertainty, and they can’t know the outcomes of many of the decisions that they have to make. Consequently, many of the steps they take are motivated mainly by their confidence in the innovation and in their understanding of the business environment in which they’re operating.

A Few Things to Know about Going into Business for Yourself

Mark Zuckerberg founded Facebook while a student at Harvard. By age 27 he built up a personal wealth of $13.5 billion. By age 31, his net worth was $37.5 billion.

So what about you? Do you ever wonder what it would be like to start your own business? You might even turn into a “serial entrepreneur” like Marcia Kilgore.[2] After high school, she moved from Canada to New York City to attend Columbia University. But when her financial aid was delayed, Marcia abandoned her plans to attend college and took a job as a personal trainer (a natural occupation for a former bodybuilder and middleweight title holder). But things got boring in the summer when her wealthy clients left the city for the Hamptons. To keep busy, she took a skin care course at a Manhattan cosmetology institute. As a teenager, she was self-conscious about her complexion and wanted to know how to treat it herself. She learned how to give facials and work with natural remedies. She started giving facials to her fitness clients who were thrilled with the results. As demand for her services exploded, she started her first business—Bliss Spa—and picked up celebrity clients, including Madonna, Oprah Winfrey, and Jennifer Lopez. The business went international, and she sold it for more than $30 million.[3]

But the story doesn’t end here; she launched two more companies: Soap and Glory, a supplier of affordable beauty products sold at Target, and FitFlops, which sells sandals that tone and tighten your leg muscles as you walk. Oprah loves Kilgore’s sandals and plugged them on her show.[4] You can’t get a better endorsement than that. Kilgore never did finish college, but when asked if she would follow the same path again, she said, “If I had to decide what to do all over again, I would make the same choices…I found by accident what I’m good at, and I’m glad I did.”

So, a few questions to consider if you want to go into business for yourself:

- How do I find a problem to solve and know it is an opportunity worth pursuing?

- How do I come up with a business idea?

- Should I build a business from scratch, buy an existing business, or invest in a franchise?

- What steps are involved in developing a business plan?

- Where could I find help in getting my business started?

- How can I increase the likelihood that I’ll succeed?

In this chapter, we’ll provide some answers to questions like these.

Why Start Your Own Business?

What sort of characteristics distinguishes those who start businesses from those who don’t? Or, more to the point, why do some people actually follow through on the desire to start up their own businesses? The most common reasons for starting a business are the following:

- To be your own boss

- To accommodate a desired lifestyle

- To achieve financial independence

- To enjoy creative freedom

- To use your skills and knowledge

The Small Business Administration (SBA) points out, though, that these are likely to be advantages only “for the right person.” How do you know if you’re one of the “right people”? The SBA suggests that you assess your strengths and weaknesses by asking yourself a few relevant questions:[5]

- Am I a self-starter? You’ll need to develop and follow through on your ideas.

- How well do I get along with different personalities? Strong working relationships with a variety of people are crucial.

- How good am I at making decisions? Especially under pressure…..

- Do I have the physical and emotional stamina? Expect six or seven work days of about twelve hours every week.

- How well do I plan and organize? Poor planning is the culprit in most business failures.

- How will my business affect my family? Family members need to know what to expect: long hours and, at least initially, a more modest standard of living.

Before we discuss why businesses fail we should consider why a huge number of business ideas never even make it to the grand opening. One business analyst cites four reservations (or fears) that prevent people from starting businesses:[6]

- Money. Without cash, you can’t get very far. What to do: line up initial financing early or at least have done enough research to have a plan to raise money.

- Security. A lot of people don’t want to sacrifice the steady income that comes with the nine-to-five job. What to do: don’t give up your day job. Run the business part-time or connect with someone to help run your business—a “co-founder.”

- Competition. A lot of people don’t know how to distinguish their business ideas from similar ideas. What to do: figure out how to do something cheaper, faster, or better.

- Lack of ideas. Some people simply don’t know what sort of business they want to get into. What to do: find out what trends are successful. Turn a hobby into a business. Think about a franchise. Find a solution to something that annoys you—entrepreneurs call this a “pain point” —and try to turn it into a business.

If you’re interested in going into business for yourself, try to regard such drawbacks as mere obstacles to be overcome by a combination of planning, talking to potential customers, and creative thinking

Who is an Entrepreneur?

You might be thinking, “All that sounds great, but I’m not an entrepreneur.” While some research has found some correlation between personality traits, like openness to new experiences, to be common among entrepreneurs; entrepreneurs are not that different from you. You can learn to act entrepreneurially and decide if starting your own business is right for you now or in the future. While many people choose to be single founders of their own company (sometimes referred to as solopreneurs) most of entrepreneurship requires working with others in some way.

Founding Teams

One of the most effective ways to get more done is to collaborate with others. Founding Teams increases your capacity and provides additional knowledge and experience from which to draw during any problem-solving process. Working with others can also provide emotional support and motivation to persist when obstacles or failures are encountered. However, there is also a cost to collaboration requiring time and effort to ensure everyone’s actions are aligned to support one another, and that everyone agrees on what those actions are and how they should be accomplished. It can get tricky when you started something together but then start to see different opportunities. A founding team can be comprised of two (most common) or more co-founders that own the company together, take the chance to capitalize on an opportunity and are usually working for free as you get things off the ground.

When organizing a team it is good to start with yourself and an understanding of what you can do. Among entrepreneurship scholars, there is a bit of a debate and mixed results regarding the best kind of founding team. A diverse founding team can give you additional expertise, expand your network and access to additional knowledge and resources, as well as providing unique ways of seeing the world when it comes to problem-solving. Whereas, a founding team where members are more similar can reduce those benefits but it can also reduce the collaboration costs if you and you co-founders have the same kinds of backgrounds, experience, and goals which make communication and coordination more efficient for shared leadership.

If you are considering working with a co-founder start first by identifying what you can do, then consider what other skills or roles would allow you to achieve your goals of launching a new venture. Some common roles within a startup generally include someone who:

- Had the idea/pathfinder;

- Manages the project/company;

- Raises money or makes connections;

- Brings in the revenues;

- Built the product (or performs the services)

Now you may be able to do all of them pretty well yourself but you still only have 24 hours in a day and may need to spend your time doing something that no one else on your team can do, or using the time to work on your business rather than in it.

Identifying Co-Founders

How do you find co-founders once you know what you are looking for? You can start with your personal networks. Share your vision or what you are looking for and ask them to refer you to anyone they think would be interested and a good fit for what you are looking for. You can also try to put yourself in places where you are more likely to meet potential co-founders whether that is online or offline. You can search according to expertise. For example, if you’re experienced on the making side but not as experienced on the business side you might go to a business networking event. If the situation were reversed and you had some business acumen but didn’t know how to actually build say a software product you might go to a hackathon to find people that know how to code and develop software. In either case be sure you are bringing something to the relationship besides just an idea. Again, when recruiting, share your passion for the vision and why you need help. It is helpful to be very clear about the role they would fill as you work together. Because you are starting a new relationship try working together on a small project that would move things forward that can be completed in a week or two. Remember, you do not have to decide on how to divide the work and the ownership right away and in fact should probably make the amount of ownership contingent upon certain milestones completed.

When Does Entrepreneurship Occur? When Does it End?

Organization Lifecycle

An organizational lifecycle refers to the different stages that organizations pass through. Similarly, industries and products also experience this same kind of lifecycle, as you’ll see in Chapter 15.

As the entrepreneur or founding team begins their journey of turning their idea into a new organization they are in the startup phase. This phase is usually characterized by large amounts of uncertainty associated with customer demand, operational capabilities, and the financial feasibility of the business model. After the startup phase the business continues on to the growth phase when founders have figured out how to provide the product profitably and are implementing systems to find and reach more customers. After that stage the mature phase occurs when growth slows and the focus is more on optimization and resource allocation rather than exploring how to create additional value. The final stage is the decline or rebirth stage. A decline occurs when there is negative growth or profits. Instead of shutting down the company many will try a rebirth stage where they attempt to change what they do and find new customers. This stage doesn’t have to be after or during a decline but can occur whenever the company chooses to explore new products or services that create new value. This is when corporate entrepreneurship happens. However, the absence of uncertainty about what to create or how to create value signals the end of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial thinking, but can resurface as the organization decides to launch a new product or faces uncertain market conditions.

Uncertainty

When we talk about uncertainty experienced by entrepreneurs we are often referring to various knowledge problems they encounter during the startup or rebirth stages. Uncertainty is one kind of knowledge problem that happens when you cannot know what action is likely to lead to a desired outcome. Other common knowledge problems entrepreneurs deal with are complexity, ambiguity, and equivocality. Complexity occurs because of the number of variables that make up a problem and the number of interactions between those variables that could influence outcomes. Ambiguity occurs when there isn’t clarity around what is important or even what might happen. Equivocality occurs when there are multiple meanings or interpretations of what is important and what is possible. Each of these knowledge problems are navigated differently. For example, suppose you find yourself confronted with a complexity or equivocality knowledge problem and decide you just need more information before you make a decision. You have just added to your problems by creating more complexity to sift through or more possible options to consider. However, for knowledge problems like uncertainty and ambiguity additional information might help you to understand what will or will not work.[7]

These knowledge problems are why many people do not attempt entrepreneurship and why startups fail despite resources and effort. The judgement and action under these conditions are what define the domain of entrepreneurship. Once there has been a reduction in uncertainty and the other knowledge problems have been overcome to at least a level of probabilistic risk then as the emphasis shifts from exploration to optimization to minimize or to estimate the known risks.

Where Does Entrepreneurship Occur?

Entrepreneurship occurs in all sorts of different settings and industries. Each industry has its own set of norms, resources, and constraints. While new ideas can happen by bringing what has worked in one industry to another; it can also be challenging because of these differences of context. The common element in all the contexts is the creation of value under conditions of uncertainty.

Value is a subjective term that represents the perceived importance or preference of a good or service. Companies are able to capture some of that value because of the price they charge for delivering that value. Customers also receive enough value that they are willing and able to pay that price and receive enough of a benefit for doing so. An entrepreneur works with potential customers to understand and create a system that can continue to produce enough value for the customer to make providing a good or service worth doing. Let’s look at different types of entrepreneurship to see how context and other factors matter in value creation.

Types of Entrepreneurship

Lifestyle versus High-Growth

One way to classify startups are by the goals or aspirations of the founders and the market size they choose to serve. On one end of the continuum, we have startups that grow up to be commonly called lifestyle businesses (also referred to as small businesses). These tend to create value for a niche group of customers that benefit from their service, product, or platform. These “small” businesses can still be very profitable and employ upwards of 500 people. This kind of business makes up the largest quantity of businesses, however, despite the sheer number of them, in total, they produce less than the type of business at the other end of the continuum,, which are usually referred to as high-growth ventures. High-growth venture startups tend to create value for much larger sized markets and become or are acquired by large and often publicly-traded corporations. They tend to employ thousands or tens of thousands of employees within one country though often have a larger global market that they serve.

Social Entrepreneurship

Traditionally all entrepreneurship seeks to systematize value creation in a way that generates enough profits to continue to create value through providing beneficial experiences or solving problems. Social entrepreneurship seeks to use a startup or company to not only generate enough profit but also enough social and/or environmental impact. This might mean addressing a social need experienced by those unable to pay for a solution on their own due to conditions of poverty. This might mean the company donates part of its revenue or profit to a charitable cause. It might also mean that the company is set up and supported to be able to provide a service at a price that normally wouldn’t be sustainable. It also might look like a charity or non-profit that uses donations and grants instead of service or product revenue to address a social issue. It could also be a for-profit entity selling a service, product, or platform through a business model that provides employment to underemployed groups or areas. In most social entrepreneurship, the startup measures their success according to not only profits, but social and environmental impact referred to as a triple bottom line. Though both entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship add value and do good, what differentiates them are the kind of constraints a founder must address.

Corporate Entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship

When we think of entrepreneurship most of the time we think of new startup companies, but entrepreneurship can happen within an existing organization as well. As was mentioned in the organization lifecycle section, as a company grows it may sell its service or product to everyone within a particular market such that the demand for what they produce eventually declines. Intrapreneurship is entrepreneurship within an established organization. Instead of closing the organization because of a lack of demand, they can redeploy resources to make additional products or improve upon old ones to extend the lifecycle of the organization. Established companies might not wait until their current product is no longer in demand. Instead they build a better product that competes against their own product before someone else can. Existing businesses may also need to change different parts of their existing business model due to changes outside the company like competitors or environmental constraints. Some companies have separate divisions dedicated to exploring ways they can create new products, such as research and development (R&D) or a corporate venture capital division, while other companies encourage and rely on employees to suggest new ideas and improvements without any changes to dedicated roles or structures. In the figure below the dotted line represents the point at which intrapreneurship tends to take place during the lifecycle of the organization.

Intrapreneurship or entrepreneurship in this corporate setting tends not to have the same constraints found in new startups, like a lack of resources or legitimacy. Entrepreneurs within corporations must instead deal with constraints like institutional inertia and internal politics. Institutional inertia comes from the fact that the company is largely known for and focused on optimizing what they do well. The company does not want to risk a reputation in the market and is reluctant to compete against itself at times.

There is also the matter of not using the company’s resources efficiently. Most choices about what project to invest in are made using assumptions about risk. Unfortunately, these same approaches do not account for conditions of uncertainty, and innovation projects are often rejected through the normal project evaluation process because they will be seen as too risky. New ideas are often met with resistance because it means someone has to do something different or because there are differences about what or how the different things should be. New ideas might not receive support because of the internal competition for resources or power. Intrapreneurship requires a slightly different skill set that is able to navigate rejection and internal politics to generate enough momentum and internal support to be able to move an idea forward.

Health Entrepreneurship

While every industry has its own set of challenges, rules, and norms, the health industry is one that is very regulated. Health entrepreneurship requires extra time to bring a new product to market. Within the United States, the Food and Drug Administration is responsible for ensuring the safety and efficacy of food, drugs, biologics, medical devices, cosmetics, and other health-related categories. This requires getting approval or a (510k) exemption from the agency before being able to sell your product. Drugs in particular need to go through a series of experiments to make sure they work as they should without side effects first on animals and then on people. Even on an accelerated track, these tests can take a lot of time and money.

Another unique aspect of the U.S. health industry for entrepreneurs to navigate is the role of the insurance companies. Insurance companies have a series of medical codes that classify different kinds of treatments or devices that some insurance plans will pay on behalf of the consumer while others will not. In addition, each insurance company has different agreements regarding how much will be paid to the medical providers. Introducing new products or services requires understanding how the insurance coding and claims process works so that the insurance payor system will be able to finance what you are doing. Just because consumers like your health product doesn’t mean they will be able to afford it without it being covered by their insurance. These kinds of systemic constraints are experienced in the health industry in addition to the uncertainty associated with entrepreneurship.

Digital Entrepreneurship

Digital entrepreneurship is a term that has surfaced as a result of the increase in the use of technological advances that can be used to start a new venture. Often these kinds of new ventures create value by leveraging existing technological platforms or services to create and automate traditional business or organizational processes. Digital entrepreneurship also encompasses the use of digital products that only exist and can be used online. Often this kind of entrepreneurship lowers the cost to start but also introduces more complexities that make it difficult to understand which process and activities will create value that can be captured and delivered in a sustainable way. The internet context also introduces additional security concerns of protecting data that is used, collected, and stored.

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Lifestyle | Creates value for a niche group of customers that benefit from their service, product, or platform and grow-up to be small businesses (less than 500 employees) |

| High growth | Creates value for much larger sized markets and grow-up to be large corporations |

| Social | Use a startup or company to not only generate enough profit but also enough social and/or environmental impact. |

| Corporate/intrapreneurship | Creates a new product or service within an existing company |

| Digital | Creates value by leveraging existing technological platforms or services to automate traditional organizational processes or other digital products that only exist and can be used online. |

| Health/life science | Creates value with products that improve health outcomes while overcoming the constraints of regulation and insurance systems |

Figure 7.7: Types of startups.

Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

Each of these types and contexts is also part of a larger ecosystem that can make it easier or more difficult to go through the entrepreneurial process. When you hear the word ecosystem your mind might flash back to the first time you were introduced to biology and saw how things were connected. An entrepreneurial ecosystem refers to a community or network of people, spaces, and available resources that interact around the creation of new ventures. Traditionally, entrepreneurial ecosystems have been geographically oriented allowing for more frequent interactions between different groups of people who exchange information, connections, and resources. However, more and more entrepreneurs are turning to online ecosystems that can provide some of the same access.

Some common spaces where you are likely to find entrepreneurs within an ecosystem include coworking spaces, incubators, and accelerators. Coworking spaces are open areas where entrepreneurs and business professionals can work out of. The spaces can be free or accessible by paying for a membership to get access. Usually, those just getting started or solopreneurs tend to leverage these spaces. Incubators are basically a bunch of offices in the same area that are rented out to particular startup companies. The rent is usually below what you would find out in the current market to provide low-cost options for those getting started. There are also usually shared spaces or services to facilitate community amongst the tenants. Accelerators are programs that provide money, space, services, and some sort of training or mentoring to startups selected to participate in their program usually in exchange for equity. Accelerators often are for a limited time frame (e.g. 3 months) and end in a demo day when startups show off or demonstrate what they have done in front of other external investors.

There are also different variations on these kinds of spaces and programs in different ecosystems. For example, on a university campus you might find something similar to the Apex Center for Entrepreneurs, located at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia, that is dedicated to helping students, faculty, and/or alumni turn their passion and purpose into action through various programs and entrepreneurial experiences. You might also find other organizations that support and provide services to entrepreneurs sponsoring these spaces. So don’t be surprised to find lawyers, accountants, consultants, bankers, and investors at these places or other entrepreneurial events and activities.

See Virginia Tech Apex Center for Entrepreneurs’ annual report here: https://www.apex.vt.edu/about/annual-report

How to do entrepreneurship?

Process/Approaches

The process of starting a new venture is a dynamic series of experiences that can be approached in a variety of ways. Some ventures may begin with an idea, others may come across a new technology, while some founders experience a problem they want to solve for themselves and discover others want a similar solution. Getting access to new resources or a desire to work with a particular group can be the start of finding ways to create value utilizing those talents, connections, or resources. This means that you can start from just about anywhere though you’ll quickly discover the need to engage in other experiences to help reduce uncertainty as you figure out how it all fits together.

While the entrepreneurial journey can be started from different places most of the time in the early stage it begins with one of the following 5 scenarios:

Each of these is an on-ramp to a similar path with slight deviations depending on the industry and contextual factors. The entrepreneurs’ path is about creating a vision, reducing the unknowns by validating assumptions associated with that vision, gathering resources needed to execute, and generating enough collective agreement to execute on the vision. It is usually best to start with the riskiest or most impactful assumption. The following assumptions are frequently found to be the challenge:

- Assumption #1: Your envisioned customer has the problem you are trying to solve

- Assumption #2: Your solution solves the problem in a unique and desirable way

- Assumption #3: You know how to find and attract enough of your customers

- Assumption #4: Your customers are willing to pay you for the solution

- Assumption #5: You can build or provide the solution

- Assumption #6: You can recruit the talent needed to create, capture, and deliver value

- Assumption #7: You can establish partnerships that allow you to scale

Assumption #1 Your envisioned customer has the problem you are trying to solve

Many people tend to come up with and get excited about product ideas or solutions without fully understanding the customers’ problems. This can be problematic because they are at risk of only paying attention to information that can be used to justify that they are right instead of figuring out what the real problem is that customers actually care about. Another version of this underlying assumption is keeping the idea a secret, for fear of someone stealing the idea, until it is ready to buy instead of getting feedback along the way. This prevents entrepreneurs from taking advantage of the perspectives and ideas of others to refine and improve the idea. In both cases, the potential downside is that the entrepreneur puts in the time, effort, and resources to build something that no one really wants. Sure it might be annoying to the customer but so what? It isn’t that big of a deal, at least enough that it would motivate them to buy something to solve it. Before falling in love with your solution make sure you understand the problem so you can create the right solution. Reducing the uncertainty associated with this assumption can be done by identifying the emotional evidence of the problem. In addition, understanding what the core problem is and not just the symptoms can reduce uncertainty around what would be valued.

Assumption #2 Your solution solves the problem in a unique and desirable way

This assumption is closely related to the first one but has more to do with gauging market timing or demand rather than understanding the motivations of your buyer. One way to figure that out is to talk with potential customers about their current experience when they encounter the problem you are interested in solving. You are listening to hear if they have the problem and are actively trying to solve it with workarounds, trying new products, or doing a bunch of research but just are not happy with the outcomes. These are the people most ready to buy and are your Early Adopters. Early adopters also tend to tell other people about new solutions through word of mouth. In order to gauge market timing, you are trying to find problem spaces in which the majority of the people you talk to are the early adopters. However, many times people will simply acknowledge the problem but just deal with it instead of trying to solve it. They’ll be annoyed or discount the problem someway. Others won’t have a problem with the current outcomes due to their own preferences or priorities. If you talk to 10 people that you believe have the problem but only 2 or 3 are actively trying to address the issue with time, money, or effort then it probably isn’t the right time. This means you will end up spending a lot of time educating your customers about the problem and convincing them it is worth solving. You can choose to do that it just usually takes a lot more time, money, and motivation to generate enough momentum.

Once you have talked to early adopters about their experiences you can decide which problems you can or want to address. Now that the problem has been identified it is time to come up with a novel, useful, and valued solution. Ideation techniques and tools help entrepreneurs come up with those solutions. This process usually involves divergent thinking that generates as many kinds of solutions as possible before engaging in convergent thinking that narrows down choices to help us make a decision and move forward. Associative thinking that encourages unlikely recombinations of concepts or contexts has also been used to inspire novel ideas. Ultimately the idea needs to address the unmet needs of your early adopters.

Assumption #3: You know how to find and attract enough of your customers

Many entrepreneurs have the thought that as soon as they launch their website or app or if they just build it then people will immediately start buying. However, in most cases, people are so inundated with information or only use particular channels to get their information thereby making it difficult to even make them aware that your startup exists. As you talk to your early adopters figure out where they heard about the last new product, service, or platform that they considered buying. That can help you identify the marketing channels to start with but don’t stop there. The cost to acquire a new customer, referred to as customer acquisition cost (CAC), is one of the most uncertain costs associated with your business that can make or break how profitable you can be. Some entrepreneurs assume those costs can be low because “social media is free”. It still costs time to create, post, and interact with content even if it is your own time. Be sure to track how much it takes to get a new follower, put an hourly wage to that time, and include that in your CAC. You are trying to create a system that can continuously find and attract those early adopters who in turn will help you get more customers. You want to try to find what is most effective but also what brings in the largest quantity of potential customers. Because not everyone that sees your social media post will click on it, and not everyone that clicks on will, go to your website. Not everyone that comes to your website will be ready to buy and in fact, you’ll have a much smaller percentage of potential customers that will result in a conversion or sale than what you started out with. Keeping track of how many potential customers move from one stage to the next can help you do a better job at finding and attracting more customers.

Assumption #4: Your customers are willing to pay you for the solution

If potential customers do make it to the point of purchase they may still be unwilling to pay the price you are asking them to pay. Determining the right price for a new product or service can be tricky. Many factors outside of your control can influence this like what the competition or alternatives for the buyer are and how much value is perceived by the customer. You can use a market comparables approach where you look at potential alternatives to what you’re selling and either offer at a premium price or a discounted price. You can also try a cost-plus approach where you figure out how much it costs you to deliver the service, product, or platform and then add a particular markup percentage that represents your profits. Or you can attempt to quantify the subjective value that your early adopters place upon what you are creating. [8]

Sometimes the value created by a startup is not in a new service, product, or platform but rather, in the way they make it available to potential customers. A startup may sell its product at a loss or at a lower profit margin if they also have additional products or services that will be purchased by that customer over a lifetime. The lifetime value of a customer (LTV) is an assumed amount that each new customer will spend in the future. In most startup cycles lifetime means the next twelve to eighteen months.

Assumption #5: You can build or provide the solution

Many a potential entrepreneur has come up with an idea but have no idea how to actually make or build their idea. Some of that may be because of a lack of personal knowledge or skill in which case you will have to recruit the talent needed but it also may be because of the limitations of current technologies. Or it can be built but not at a cost anyone is ready to pay for. Remember as an entrepreneur you are wanting to create a system that can continuously create value. But you have to do it the first time before you can grow or scale it. This usually involves creating a prototype or a simple version of the product or service to learn what it would take to produce it and if it can work as envisioned. A prototype doesn’t need to be completely functional in order to learn. You could even use competitors’ products as your prototype and find out what needs to change or stay the same. Regardless in most cases, you’ll make multiple versions of a product or service after having received feedback from potential customers before arriving at the finished outcome, which includes a repeatable process.

Assumption #6: You can recruit talent needed to create, capture, & deliver value

This builds off of the prior assumption that you don’t have the necessary skills or knowledge to create, capture, and deliver value to your customers in a profitable way. This is often where passion for an idea can bring similarly passionate people together to work towards achieving a better future. However, while people might be interested in an idea, they are also interested in being well paid on a consistent basis. A lack of ability to pay people’s salaries puts startups at a considerable disadvantage when recruiting. However, you may be able to offer longer-term benefits such as equity or the chance to gain experience by working on things they’re not qualified to attempt in the general labor market. Or you can find experienced individuals who are willing to be a part of your advisory board and give you a few hours every month or so to help you know things that you are not aware of.

Assumption #7: You can establish partnerships that allow you to scale

Most of the time startups can’t do everything and need to partner with others. This might be suppliers or raw material providers that provide parts or resources, Or it could be manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers, or retailers. It might also look like bankers, accountants, consultants, or independent contractors who provide expertise on particular parts of your business. However, like the prior recruiting assumption they tend to want to be paid or guaranteed they won’t lose money for helping you. Finding partners who are willing to work with you as you figure out the best way can be challenging. Often personal networks and referrals are utilized to find partners willing to take a chance on a new startup. Contracts also become a common tool to spell out expectations and recourse if things do not go well.

Each assumption or area has experiences, milestones, or artifacts, a few of which we’ve mentioned above. The image below is an attempted visual roadmap of various stages/artifacts.

Startup Financing

While a lot of the process can be done without any money there are eventual costs that need to be covered to be able to create, capture, and deliver value. Often founders struggle to get started because of a lack of resources, this section talks about different ways the startup can be funded along a continuum that goes from straightforward to more complex.

| Level | Name | Team | Problem and vision | Value prop | Product | Market | Business model | Scale | Exit | Type of funding typically closed at this level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Exit in sight | Team positioned to navigate M&A, IPO | Global leader in stated vision | Cited as the top solution in the industry solving this problem | Product recognized as top in industry | Clear line-of-sight to industry dominance | Minimum 2x revenue growth for multiple years | Strong unit economics for multiple customer segments | Growth with exit | Acquirers |

| 8 | Scaling up | Team is recognized as market leaders in the industry | Systems-level change validated | Multiple renewals with low sales effort. Customers in multiple markets love the product | Strong customer product feedback in multiple markets | Brand established. Hard-to-beat partnerships for distribution, marketing, and growth | MOM revenue meets industry standard | Growth of customer base accelerates month-to-month | Team has turned down acquisition offer | Close institutional VC for recurring revenue + growth |

| 7 | Hitting product-market fit | C-suite as good or better than founding CEO and can stay with company through its growth and exit phases | Impact is successfully validated | Majority of first sales in target market are inbound | Product is built for scale and additional offerings in progress | Sales cycles meet or exceed industry standard | Business model validated—validation of strong unit economics | Evidence of strong unit economics across multiple markets | Team has strong relationships with multiple acquirers | Close institutional VC for recurring revenue + growth |

| 6 | Moving beyond early adopters | Team has proven sales, product dev skills, and management ability to support a growing team for scale | Sales validate impact tied to solution and grow as solution scales | Sales beyond initial target customers. Customers love it and are referring the product to others | Complete product with strong user experience feedback | Supply/distribution partners see their success aligned with the company's success | Sales begin to map to projections. Evidence of decreasing CAC with growing customer base buying at target price | Company has cleared regulatory challenges and (if applicable) is implementing a strong IP strategy | Team has identified specific acquirer(s) or other exit environment | Close institutional VC for 1st sales, market expansion |

| 5 | Providing a profitable business model | Team has cleat sales/ops understanding and strategy | Evidence of impact tied to solution—the company has evidence that by growing the business, company solves the problem | Target customers love the product and want to keep using it | Fully functional prototype with completion of product for wide commercial distribution in sight | Team is having conversations with strategic partners to capture their market faster/cheaper than the competition | Financial model with evidence of valid projections to reach positive unit economics | Vision and initial evidence of positive unit economics in two markets | Inbound interest from large strategics | Close round with angel and early VC |

| 4 | Validating an investable market | Team has clear understanding of how their target market operates and has string industry contacts in this market | The company can articulate system-level change—how this solution would transform the industry | Evidence of differentiation through initial target customer feedback that the solution solves their problem significantly better than others in the market | Team has cleat understanding of product development costs and how to build the initial product cos-effectively | Evidence of $1B+ total addressable market | Team has financial model with cost and revenue projections articulated and a strategy for hitting these projections | Initial evidence that multiple types of customers find value in the solution or in an extension of the product that the company is well-positioned to develop | Evidence of growth trajectory that cound lead to IPO, acquisition, or self-liquidating exit | - Angel/seed funding starts - Friends, family, bootstrap |

| 3 | Solidifying the value proposition | Team has technical ability to build fully functional product and has a clear understanding of the value chain and cost structures in their industry | The company can articulate why they're the best ones to solve this problem | Evidence that customers will pay the target price. For B2C-100 customers, for B2B-5 customers and conversations with multiple stakeholders in each | Team has built a working prototype and a product roadmap | Initial evidence through sales that team can capture initial target market | Team can articulate projected costs along the value chain and target cost points to reach positive unit economics | Clear strategy to move to multiple markets | Initial evidence that the solution already solves the problem better than any incumbents | - Grants for R&D (hardware) - Friends, family, bootstrap |

| 2 | Setting the vision | Team has senior members with lived experience of the problem and/or deep understanding of their target customer's problem | The team can solve the problem and can articulate its vision at scale—what does the world look like if they succeed? | The team has potential customers who provide evidence that solution solves key pain point—product is a painkiller, not vitamin | Team has a basic low-fidelity prototype that solves the problem | Team understands any regulatory hurdles to entering the market and has a strategy to overcome them | Company can point to pricing and business models of similar products in the industry as further evidence that their revenue assumptions hold | Initial evidence that multiple markets experience this problem | Vision for growth has company solving a large piece of the global problem in 10 years | - Grants for R&D (hardware) - Friends, family, bootstrap |

| 1 | Establishing the founding team | Strong founding team—at least 2 people with differentiated skillsets | Team has identified a specific, important, and large problem | Team has identified their hypothesis of their target customer—the specific type of person whose problem they are solving | Team has ability to develop low-fidelity prototype and has freedom to operate—not blocked by other patents | Team can clearly articulate total addressable market, the percentage they will capture, and initial target market | Team has identified an outline of revenue model | Team has identified multiple possible markets or customer segments and has aspiration to scale | Team understands what an exit is and has a vision for how they will ultimately provide a return for their investors | Friends, family, bootstrap |

Figure 7.11: Different types of funding for viral pathways.

Bootstrapping is when the founders use their own funds to start a company. This might be income from their full-time job, it might savings, or the use of their personal credit cards. They can also get favorable invoice or line of credit terms from suppliers so that they can have the product made and sell it before they have to pay for the cost of production. However, this often requires a personal guarantee from the founder exposing their personal assets to risk. As you progress along this continuum, founders might be funded with a gift or loan by friends or family members who want to help them start the business. Sometimes government institutions like universities or other ecosystem stakeholders might provide grants or competition prizes that allow the founder to get started. Some founders can pre-sell their ideas getting the money prior to building a product like on crowdfunding platforms. For those that need a lot of money to start their venture due to the kinds of equipment or property needed to create value, they may need to pursue debt financing like a bank loan. Others might be able to convince suppliers or manufacturers to extend a line of credit so that they have time to sell the service or products before the invoice comes due.

All these are ways to get to the primary funding mechanism of any business, revenue from paying customers. However, even if a startup has initial revenue, it may not be able to afford the changes needed to support rapid growth to reach large amounts of customers. This is when external investors may become involved. Investors will give the founders money in exchange for some equity or ownership of the company. Investors, in general, want a return on their investment which means the value of the company they invest in must increase considerably and have a way for them to get their money back. This becomes important for founders to understand as not all companies are investable due to the market size or growth potential. It doesn’t mean that they won’t be profitable just not enough for investors to get what they want or need. Below is an example of a Venture Investment-Readiness and Awareness Levels framework used by venture capital firms to help startups understand when they would be ready to be considered for investment.

The two primary types of investors in investable startups are angels and venture capitalists. Angel investors invest their own money either on their own or with a group of others. They might invest for a variety of reasons (a product they’d use, want to be involved in something exciting, desire to help a passionate founder, etc.) besides just the chance to make money but are often hoping to get a return on their money in a three to a five-year window through an acquisition or during the next round (Seed, Series A, B, C, etc.) of funding with venture capitalists. Venture capitalists invest primarily other people’s money promising high returns in seven to ten years to those individuals who contribute to their fund. The venture capitalists then search for a portfolio of high-growth ventures that serve large amounts of customers. They hope that some of the ventures will be acquired and that at least one of them will get really big, really fast to become a publicly-traded stock so they can cash out and return the promised money to their clients. Angel investors invest smaller amounts than venture capitalists but also don’t need the company to grow as much as the venture capitalist to get the desired return. Whereas venture capitalists have a fiduciary responsibility or to act in good faith on behalf of their clients. The tricky part is being able to tell which startups will be the ones to be that high-growth success with all the uncertainty that exists.

Beyond Founding

A key aspect of the entrepreneurial journey is the creation of a service, product, or platform. In order to build a system that creates value through one of these creations requires some experimentation and rapid learning to develop an offering that is enough to merit revenue transactions. Besides launching your own company the skills developed during the commercialization process tend to be those used by product managers within existing corporations and are often a career path for those that study entrepreneurship in higher education.

Distinguishing Entrepreneurs from Small Business Owners

Though most entrepreneurial ventures begin as small businesses, not all small business owners are entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs are innovators who start companies to create new or improved products. They strive to meet a need that’s not being met, and their goal is to grow the business and eventually expand into other markets.

In contrast, many people either start or buy small businesses for the sole purpose of providing an income for themselves and their families. They do not intend to be particularly innovative, nor do they plan to expand significantly. This desire to operate is what’s sometimes called a “lifestyle business.”[9] The neighborhood pizza parlor or beauty shop, the self-employed consultant who works out of the home, and even a local printing company—many of these are typically lifestyle businesses.

The Importance of Small Business to the US Economy

What Is a “Small Business”?

To assess the value of small businesses to the US economy, we first need to know what constitutes a small business. Let’s start by looking at the criteria used by the Small Business Administration. According to the SBA, a small business is one that is independently owned and operated, exerts little influence in its industry, and (with a few exceptions) has fewer than 500 employees.[10]

Why Are Small Businesses Important?

There are more than 30.7 million small businesses in this country, and they generate about 47.3 percent of jobs in the US.[11] The millions of individuals who have started businesses in the United States have shaped the business world as we know it today. Some small business founders like Henry Ford and Thomas Edison have even gained places in history. Others, including Bill Gates (Microsoft), Sam Walton (Wal-Mart), Steve Jobs (Apple Computer), and Larry Page and Sergey Brin (Google), have changed the way business is done today.

Aside from contributions to our general economic well-being, founders of small businesses also contribute to growth and vitality in specific areas of economic and socioeconomic development. In particular, small businesses do the following:

- Create jobs

- Spark innovation

- Provide opportunities for many people, including women and minorities, to achieve financial success and independence

In addition, they complement the economic activity of large organizations by providing them with components, services, and distribution of their products. Let’s take a closer look at each of these contributions.

Job Creation

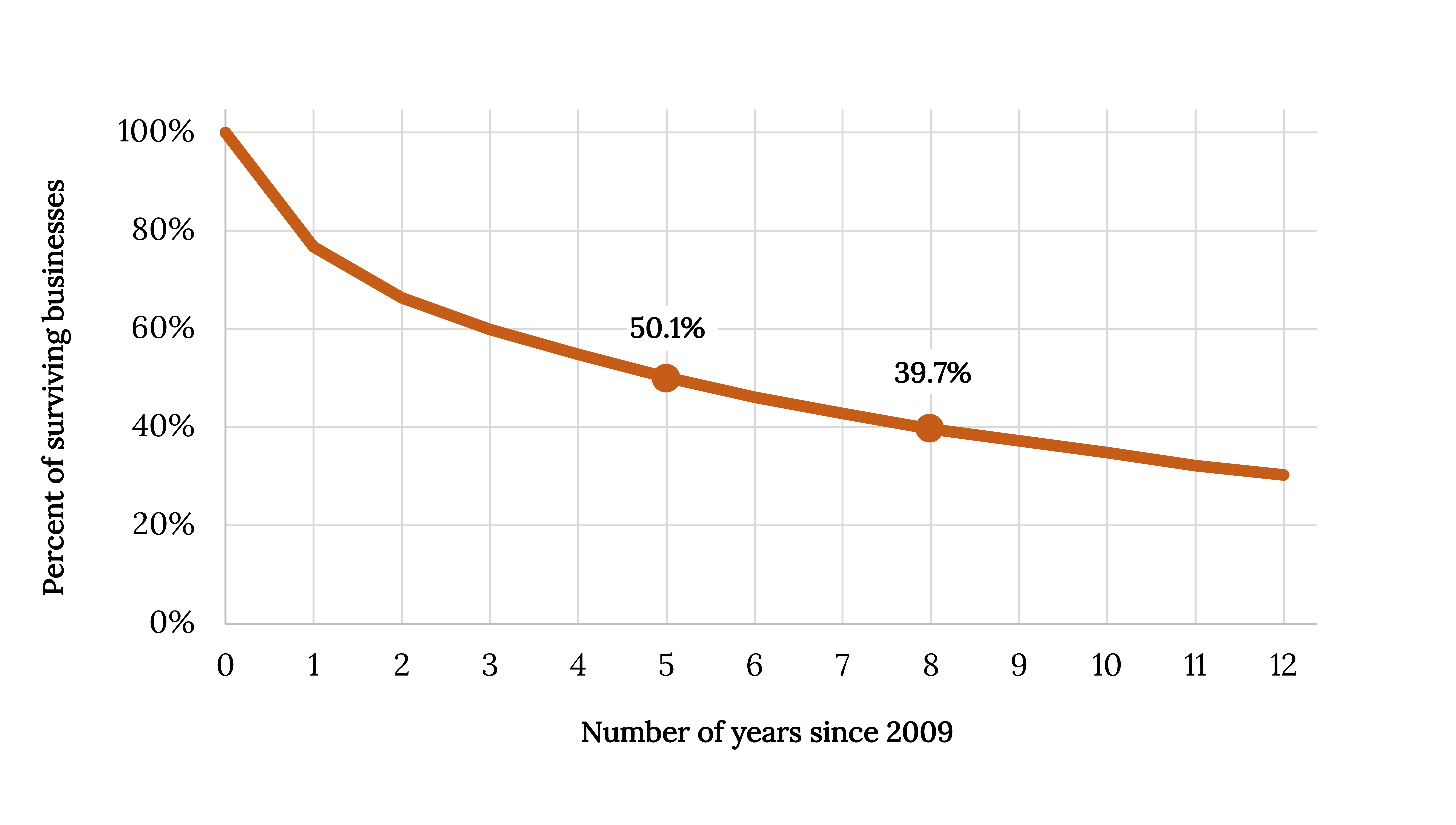

The majority of US workers first entered the business world working for small businesses. Although the split between those working in small companies and those working in big companies is about even, small firms hire more frequently and fire more frequently than do big companies.[12] Why is this true? At any given point in time, lots of small companies are started and some expand. These small companies need workers and so hiring takes place. But the survival and expansion rates for small firms is poor, and so, again at any given point in time, many small businesses close or contract and workers lose their jobs. Fortunately, over time more jobs are added by small firms than are taken away, which results in a net increase in the number of workers, as seen in figure 7.12.

| Job gains | Job losses | Net change |

|---|---|---|

| Openings: 85.5 | Closings: 82.1 | |

| Expansions: 326.5 | Contractions: 320.7 | |

| 412 | 402.8 | 9.2 |

Figure 7.12: Small business job gains and losses, 2000-2021 (in millions of jobs).

The size of the net increase in the number of workers for any given year depends on a number of factors, with the economy being at the top of the list. A strong economy encourages individuals to start small businesses and expand existing small companies, which adds to the workforce. A weak economy does just the opposite: discourages start-ups and expansions, which decreases the workforce through layoffs. Figure 7.12 reports the job gains from start-ups and expansions and job losses from business closings and contractions.

Innovation

Given the financial resources available to large businesses, you’d expect them to introduce virtually all the new products that hit the market. Yet according to the SBA, small companies develop more patents per employee than do larger companies. During a recent four-year period, large firms generated 1.7 patents per hundred employees, while small firms generated an impressive 26.5 patents per employee.[13] Over the years, the list of important innovations by small firms has included the airplane, air-conditioning, DNA “fingerprinting,” and overnight national delivery.[14]

Small business owners are also particularly adept at finding new ways of doing old things. In 1994, for example, a young computer-science graduate working on Wall Street came up with the novel idea of selling books over the Internet. During the first year of operations, sales at Jeff Bezos’ new company—Amazon.com—reached half a million dollars. In less than 20 years, annual sales had topped $107 billion.[15] Not only did his innovative approach to online retailing make Bezos enormously rich, but it also established a viable model for the e-commerce industry.

Why are small businesses so innovative? For one thing, they tend to offer environments that appeal to individuals with the talent to invent new products or improve the way things are done. Fast decision making is encouraged, their research programs tend to be focused, and their compensation structures typically reward top performers.

According to one SBA study, the supportive environments of small firms are roughly 13 times more innovative per employee than the less innovation-friendly environments in which large firms traditionally operate.[16]

The success of small businesses in fostering creativity has not gone unnoticed by big businesses. In fact, many large companies have responded by downsizing to act more like small companies. Some large organizations now have separate work units whose purpose is to spark innovation. Individuals working in these units can focus their attention on creating new products that can then be developed by the company.

Opportunities for Women and Minorities

Small business is the portal through which many people enter the economic mainstream. Business ownership allows individuals, including women and minorities, to achieve financial success, as well as pride in their accomplishments. Figure 7.14 gives you an idea of how many American businesses are owned by women and minorities.

| Business owners | 2007 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Women-owned | 37.5% | 19.9% |

| Hispanic-owned | 5.9% | 5.8% |

| Asian-owned | 5.6% | 10.1% |

| Black-owned | 3.6% | 2.2% |

| American Indian and Alaska Native-owned | 0.8% | 0.4% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander-owned | 0.2% | 0.1% |

Figure 7.14: Percent of all businesses owned by women and minorities.

What Industries Are Small Businesses In?

If you want to start a new business, you probably should avoid certain types of businesses. You’d have a hard time, for example, setting up a new company to make automobiles or aluminum, because you’d have to make tremendous investments in property, plant, and equipment, and raise an enormous amount of capital to pay your workforce. These large, up-front investments present barriers to entry.

Fortunately, plenty of opportunities are still available. Many types of businesses require reasonable initial investments, and not surprisingly, these are the ones that usually present attractive small business opportunities.

Industries by Sector

Let’s define an industry as a group of companies that compete with one another to sell similar products. We’ll focus on the relationship between a small business and the industry in which it operates, dividing businesses into two broad types of industries, or sectors: the goods-producing sector and the service-producing sector.

- The goods-producing sector includes all businesses that produce tangible goods. Generally speaking, companies in this sector are involved in manufacturing, construction, and agriculture.

- The service-producing sector includes all businesses that provide services but don’t make tangible goods. They may be involved in retail and wholesale trade, transportation, finance, entertainment, recreation, accommodations, food service, and any number of other ventures.

About 20 percent of small businesses in the United States are concentrated in the goods-producing sector. The remaining 80 percent are in the service sector.[17] The high concentration of small businesses in the service-producing sector reflects the makeup of the overall US economy. Over the past 50 years, the service-producing sector has been growing at an impressive rate. In 1960, for example, the goods-producing sector accounted for 38 percent of GDP, the service-producing sector for 62 percent. By 2015, the balance had shifted dramatically, with the goods-producing sector accounting for only about 21 percent of GDP.[18]

Goods-Producing Sector

The largest areas of the goods-producing sector are construction and manufacturing. Construction businesses are often started by skilled workers, such as electricians, painters, plumbers, and home builders, and they generally work on local projects. Though manufacturing is primarily the domain of large businesses, there are exceptions.

How about making something out of trash? Daniel Blake never followed his mother’s advice at dinner when she told him to eat everything on his plate. When he served as a missionary in Puerto Rico, Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao after his first year in college, he noticed that the families he stayed with didn’t either. But they didn’t throw their uneaten food into the trash. Instead they put it on a compost pile and used the mulch to nourish their vegetable gardens and fruit trees. While eating at an all-you-can-eat breakfast buffet back home at Brigham Young University, Blake was amazed to see volumes of uneaten food in the trash. This triggered an idea: why not turn the trash into money? Two years later, he was running his company—EcoScraps—collecting 40 tons of food scraps a day from 75 grocers and turning it into high-quality potting soil that he sells online and to nurseries. His profit has reach almost half a million dollars on sales of $1.5 million.[19]

Service-Producing Sector

Many small businesses in this sector are retailers—they buy goods from other firms and sell them to consumers, in stores, by phone, through direct mailings, or over the Internet. In fact, entrepreneurs are turning increasingly to the Internet as a venue for start-up ventures. Take Tony Roeder, for example, who had a fascination with the red Radio Flyer wagons that many of today’s adults had owned as children. In 1998, he started an online store through Yahoo! to sell red wagons from his home. In three years, he turned his online store into a million-dollar business.[20]

Other small business owners in this sector are wholesalers—they sell products to businesses that buy them for resale or for company use. A local bakery, for example, is acting as a wholesaler when it sells desserts to a restaurant, which then resells them to its customers. A small business that buys flowers from a local grower (the manufacturer) and resells them to a retail store is another example of a wholesaler.

A high proportion of small businesses in this sector provide professional, business, or personal services. Doctors and dentists are part of the service industry, as are insurance agents, accountants, and lawyers. So are businesses that provide personal services, such as dry cleaning and hairdressing.

David Marcks, for example, entered the service industry about 14 years ago when he learned that his border collie enjoyed chasing geese at the golf course where he worked. While geese are lovely to look at, they can make a mess of tees, fairways, and greens. That’s where Marcks’ company, Geese Police, comes in: Marcks employs specially trained dogs to chase the geese away. He now has 27 trucks, 32 border collies, and five offices. Golf courses account for only about 5 percent of his business, as his dogs now patrol corporate parks and playgrounds as well.[21] Figure 7.15 provides a more detailed breakdown of small businesses by industry.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Business Ownership

Do you want to be a business owner someday? Before deciding, you might want to consider the following advantages and disadvantages of business ownership.[22]

Advantages of Small Business Ownership

Being a business owner can be extremely rewarding. Having the courage to take a risk and start a venture is part of the American dream. Success brings with it many advantages:

- Independence. As a business owner, you’re your own boss. You can’t get fired. More importantly, you have the freedom to make the decisions that are crucial to your own business success.

- Lifestyle. Owning a small business gives you certain lifestyle advantages. Because you’re in charge, you decide when and where you want to work. If you want to spend more time on non-work activities or with your family, you don’t have to ask for the time off. Given today’s technology, if it’s important that you be with your family all day, you can run your business from your home.

- Financial rewards. In spite of high financial risk, running your own business gives you a chance to make more money than if you were employed by someone else. You benefit from your own hard work.

- Learning opportunities. As a business owner, you’ll be involved in all aspects of your business. This situation creates numerous opportunities to gain a thorough understanding of the various business functions.

- Creative freedom and personal satisfaction. As a business owner, you’ll be able to work in a field that you really enjoy. You’ll be able to put your skills and knowledge to use, and you’ll gain personal satisfaction from implementing your ideas, working directly with customers, and watching your business succeed.

Disadvantages of Small Business Ownership

As the little boy said when he got off his first roller-coaster ride, “I like the ups but not the downs!” Here are some of the risks you run if you want to start a small business:

- Financial risk. The financial resources needed to start and grow a business can be extensive. You may need to commit most of your savings or even go into debt to get started. If things don’t go well, you may face substantial financial loss. In addition, there’s no guaranteed income. There might be times, especially in the first few years, when the business isn’t generating enough cash for you to live on.

- Stress. As a business owner, you are the business. There’s a bewildering array of things to worry about—competition, employees, bills, equipment breakdowns, etc.. As the owner, you’re also responsible for the well-being of your employees.

- Time commitment. People often start businesses so that they’ll have more time to spend with their families. Unfortunately, running a business is extremely time-consuming. In theory, you have the freedom to take time off, but in reality, you may not be able to get away. In fact, you’ll probably have less free time than you’d have working for someone else. For many entrepreneurs and small business owners, a 40-hour workweek is a myth. Vacations will be difficult to take and will often be interrupted. In recent years, the difficulty of getting away from the job has been compounded by cell phones, iPhones, Internet-connected laptops and iPads, and many small business owners have come to regret that they’re always reachable.

- Undesirable duties. When you start up, you’ll undoubtedly be responsible for either doing or overseeing just about everything that needs to be done. You can get bogged down in detail work that you don’t enjoy. As a business owner, you’ll probably have to perform some unpleasant tasks, like firing people.

In spite of these and other disadvantages, most small business owners are pleased with their decision to start a business. A survey conducted by the Wall Street Journal and Cicco and Associates indicates that small business owners and top-level corporate executives agree overwhelmingly that small business owners have a more satisfying business experience. Interestingly, the researchers had fully expected to find that small business owners were happy with their choices; they were, however, surprised at the number of corporate executives who believed that the grass was greener in the world of small business ownership.[23]

Starting a Business

Starting a business takes talent, determination, hard work, and persistence. It also requires a lot of research and planning. Before starting your business, you should appraise your strengths and weaknesses and assess your personal goals to determine whether business ownership is for you.[24]

Questions to Ask Before You Start a Business

If you’re interested in starting a business, you need to make decisions even before you bring your talent, determination, hard work, and persistence to bear on your project.

Here are the basic questions you’ll need to address:

- What, exactly, is my business idea? Is it feasible?

- What industry do I want to enter?

- What will be my competitive advantage?

- Do I want to start a new business, buy an existing one, or buy a franchise?

- What form of business organization do I want?

After making these decisions, you’ll be ready to take the most important step in the entire process of starting a business: you must describe your future business in the form of a business plan—a document that identifies the goals of your proposed business and explains how these goals will be achieved. Think of a business plan as a blueprint for a proposed company: it shows how you intend to build the company and how you intend to make sure that it’s sturdy. You must also take a second crucial step before you actually start up your business: You need to get financing—the money that you’ll need to get your business off the ground.

The Business Idea

For some people, coming up with a great business idea is a gratifying adventure. For most, however, it’s a daunting task. The key to coming up with a business idea is identifying something that customers want—or, perhaps more importantly, filling an unmet need. Your business will probably survive only if its purpose is to satisfy its customers—the ultimate users of its goods or services. In coming up with a business idea, don’t ask, “What do we want to sell?” but rather, “What does the customer want to buy?”[25]

To come up with an innovative business idea, you need to be creative. If your idea is innovative enough, it may be considered intellectual property, a right that can be protected under the law. Prior experience accounts for the bulk of new business idea and also increases your chances of success. Take Sam Walton, the late founder of Wal-Mart. He began his retailing career at JCPenney and then became a successful franchiser of a Ben Franklin five-and-dime store. In 1962, he came up with the idea of opening large stores in rural areas, with low costs and heavy discounts. He founded his first Wal-Mart store in 1962, and when he died 30 years later, his family’s net worth was $25 billion.[26]

Industry experience also gave Howard Schultz, a New York executive for a housewares company, his breakthrough idea. In 1981, Schultz noticed that a small customer in Seattle—Starbucks Coffee, Tea and Spice—ordered more coffeemaker cone filters than Macy’s and many other large customers. So he flew across the country to find out why. His meeting with the owner-operators of the original Starbucks Coffee Co. resulted in his becoming part-owner of the company. Schultz’s vision for the company far surpassed that of its other owners. While they wanted Starbucks to remain small and local, Schultz saw potential for a national business that not only sold world-class-quality coffee beans but also offered customers a European coffee-bar experience. After attempting unsuccessfully to convince his partners to try his experiment, Schultz left Starbucks and started his own chain of coffee bars, which he called Il Giornale (after an Italian newspaper). Two years later, he bought out the original owners and reclaimed the name Starbucks.[27]

Ownership Options

As we’ve already seen, you can become a small business owner in one of three ways— by starting a new business, buying an existing one, or obtaining a franchise. Let’s look more closely at the advantages and disadvantages of each option.

Starting from Scratch

The most common—and the riskiest—option is starting from scratch. This approach lets you start with a clean slate and allows you to build the business the way you want. You select the goods or services that you’re going to offer, secure your location, and hire your employees, and then it’s up to you to develop your customer base and build your reputation. This was the path taken by Andres Mason who figured out how to inject hysteria into the process of bargain hunting on the Web. The result is an overnight success story called Groupon.[28] Here is how Groupon (a blend of the words “group” and “coupon”) works: A daily email is sent to 6.5 million people in 70 cities across the United States offering a deeply discounted deal to buy something or to do something in their city. If the person receiving the email likes the deal, he or she commits to buying it. But, here’s the catch, if not enough people sign up for the deal, it is cancelled. Groupon makes money by keeping half of the revenue from the deal. The company offering the product or service gets exposure. But stay tuned: the “daily deals website isn’t just unprofitable—it’s bleeding hundreds of millions of dollars.”[29] As with all start-ups cash is always a challenge.

Buying an Existing Business

If you decide to buy an existing business, some things will be easier. You’ll already have a proven product, current customers, active suppliers, a known location, and trained employees. You’ll also find it much easier to predict the business’s future success.

There are, of course, a few bumps in this road to business ownership. First, it’s hard to determine how much you should pay for a business. You can easily determine how much things like buildings and equipment are worth, but how much should you pay for the fact that the business already has steady customers?

In addition, a business, like a used car, might have performance problems that you can’t detect without a test drive (an option, unfortunately, that you don’t get when you’re buying a business). Perhaps the current owners have disappointed customers; maybe the location isn’t as good as it used to be. You might inherit employees that you wouldn’t have hired yourself. Careful study called due diligence is necessary before going down this road.

Getting a Franchise

Lastly, you can buy a franchise. A franchiser (the company that sells the franchise) grants the franchisee (the buyer—you) the right to use a brand name and to sell its goods or services. Franchises market products in a variety of industries, including food, retail, hotels, travel, real estate, business services, cleaning services, and even weight-loss centers and wedding services. Figure 7.17 lists the top 10 franchises according to Entrepreneur magazine for 2015, 2020, and 2022.

| Ranking | 2015 | 2020 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hampton by Hilton | Dunkin' | Taco Bell | |

| 2 | Anytime Fitness | Taco Bell | The UPS Store | |

| 3 | Subway | McDonald's | Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen | |

| 4 | Jack in the Box | Sonic Drive-In | Jersey Mike's Subs | |

| 5 | Supercuts | The UPS Store | Culver's | |

| 6 | Jimmy John's Gourmet Sandwiches | Ace Hardware | Kumon | |

| 7 | Servpro | Planet Fitness | Planet Fitness | |

| 8 | Denny's | Jersey Mike's Subs | Servpro | |

| 9 | Pizza Hut | Culver's | 7-Eleven | |

| 10 | 7-Eleven | Pizza Hut | Tropical Smoothie Cafe |

Figure 7.17: Entrepreneur’s top franchises (2015, 2020, 2022).

As you can see from figure 7.18 below, the popularity of franchising has been growing quickly since 2011. Although the economic downturn decreased the number of franchises between 2008-11, note that the overall value of franchise outputs steadily increased. A new franchise outlet opens once every eight minutes in the United States, where one in ten businesses is now a franchise. Franchises employ eight million people (13 percent of the workforce) and account for 17 percent of all sales in the US ($1.3 trillion).[30]

In addition to the right to use a company’s brand name and sell its products, the franchisee gets help in picking a location, starting and operating the business, and benefits from advertising done by the franchiser. Essentially, the franchisee buys into a ready-to-go business model that has proven successful elsewhere, also getting other ongoing support from the franchiser, which has a vested interest in her success.