Chapter 1 Teamwork in Business

Learning Objectives

- Define a team and describe its key characteristics.

- Explain why organizations use teams and describe different types of teams.

- Explain why teams may be effective or ineffective.

- Identify factors that contribute to team cohesiveness.

- Understand the importance of learning to participate in team-based activities.

- Identify the skills needed by team members and the roles that members of a team might play.

- Learn how to survive team projects in college (and actually enjoy yourself).

- Explain the skills and behaviors that foster effective team leadership.

The Team with the RAZR’s Edge

The publicly traded company Motorola Mobility was created when Motorola spun off its Mobile Devices division, creating a new entity. The newly-formed company’s executive team was under intense pressure to come out with a smartphone that could grab substantial market share from Apple’s iPhone 4S and Samsung’s Galaxy Nexus. To do this, the team oversaw the design of an Android version of the Motorola RAZR, which was once the best-selling phone in the world. The hope of the executive team was that past customers who loved the RAZR would love the new ultra-thin smartphone—the Droid RAZR. The Droid RAZR was designed by a team, as are other Motorola products. To understand the team approach at Motorola, let’s review the process used to design the RAZR.

By winter 2003, the company that for years had run in circles around their competition had been bumped from the top spot in worldwide sales.[1] Motorola found itself stuck in the number-three slot. Their sales had declined because consumers were less than enthusiastic about the uninspired style of Motorola phones, and for many people, style is just as important in picking a cell phone as features. As a reviewer for one industry publication put it, “We just want to see the look on people’s faces when we slide [our phones] out of our pockets to take a call.”

Yet there was a glimmer of hope at Motorola. Despite its recent lapse in cell phone fashion sense, Motorola still maintained a concept-phone unit—a group responsible for designing futuristic new product features such as speech-recognition capability, flexible touchscreens, and touch-sensitive body covers. In every concept-phone unit, developers engage in an ongoing struggle to balance the two often-opposing demands of cell phone design: building the smallest possible phone with the largest possible screen. The previous year, Motorola had unveiled the rough model of an ultra-trim phone—at 10 millimeters, about half the width of the average flip-top or “clamshell” design. It was on this concept that Motorola decided to stake the revival of its reputation as a cell phone maker who knew how to package functionality with a wow factor.

The next step in developing a concept phone is actually building it. Teamwork becomes critical at this point. The process requires some diversity in expertise. An electronics engineer, for example, knows how to apply energy to transmit information through a system but not how to apply physics to the design and manufacture of the system; that’s the specialty of a mechanical engineer. Engineers aren’t designers—the specialists who know how to enhance the marketability of a product through its aesthetic value. Designers bring their own unique value to the team.

In addition, when you set out to build any kind of innovative high-tech product, you need to become a master of trade-offs—in Motorola’s case, compromises resulted from the demands of state-of-the-art functionality on one hand and fashionable design on the other. Negotiating trade-offs is a team process: it takes at least two people to resolve design disputes.

The responsibility for assembling and managing the Motorola “thin-clam” team fell to veteran electronic engineer Roger Jellicoe. His mission: create the world’s thinnest phone, do it in one year, and try to keep it a secret. Before the project was completed, the team had grown to more than twenty members, and with increased creative input and enthusiasm came increased confidence and clout. Jellicoe had been warned by company specialists in such matters that no phone wider than 49 millimeters could be held comfortably in the human hand. When the team had finally arrived at a satisfactory design that couldn’t work at less than 53 millimeters, they ignored the “49 millimeters warning,” built a model, passed it around, and came to a consensus: as one team member put it, “People could hold it in their hands and say, ‘Yeah, it doesn’t feel like a brick.’” Four millimeters, they decided, was an acceptable trade-off, and the new phone went to market at 53 millimeters. While small by today’s standards, at the time, 53 millimeters was a gamble.

Team members liked to call the design process the “dance.” Sometimes it flowed smoothly and sometimes people stepped on one another’s toes, but for the most part, the team moved in lockstep toward its goal. After a series of trade-offs about what to call the final product (suggestions ranged from Razor Clam to V3), Motorola’s new RAZR was introduced in July 2004. Recall that the product was originally conceived as a high-tech toy—something to restore the luster to Motorola’s tarnished image. It wasn’t supposed to set sales records, and sales in the fourth quarter of 2004, though promising, were in fact fairly modest. Back in September, however, a new executive named Ron Garriques had taken over Motorola’s cell phone division; one of his first decisions was to raise the bar for RAZR. Disregarding a 2005 budget that called for sales of two million units, Garriques pushed expected sales for the RAZR up to twenty million. The RAZR topped that target, shipped ten million in the first quarter of 2006, and hit the fifty-million mark at midyear. Talking on a RAZR, declared hip-hop star Sean “P. Diddy” Combs, “is like driving a Mercedes versus a regular ol’ ride.”[2]

Jellicoe and his team were invited to attend an event hosted by top executives, receiving a standing ovation, along with a load of stock options. One of the reasons for the RAZR’s success, said Jellicoe, was that “it took the world by surprise. Very few Motorola products do that.” For a while, the new RAZR was the best-selling phone in the world.

The Team and the Organization

What Is a Team? How Does Teamwork Work?

A team (or a work team) is a group of people with complementary skills who work together to achieve a specific goal.[3] In the case of Motorola’s RAZR team, the specific goal was to develop (and ultimately bring to market) an ultra-thin cell phone that would help restore the company’s reputation. The team achieved its goal by integrating specialized but complementary skills in engineering and design and by making the most of its authority to make its own decisions and manage its own operations.

Teams versus Groups

As Bonnie Edelstein, a consultant in organizational development suggests, “A group is a bunch of people in an elevator. A team is also a bunch of people in an elevator, but the elevator is broken.”[4] This distinction may be a little oversimplified, but as our tale of teamwork at Motorola reminds us, a team is clearly something more than a mere group of individuals. In particular, members of a group—or, more accurately, a working group—go about their jobs independently and meet primarily to work towards a shared objective. A group of department-store managers, for example, might meet monthly to discuss their progress in cutting plant costs. However, each manager is focused on the goals of his or her department because each is held accountable for meeting those goals.

Some Key Characteristics of Teams

To put teams in perspective, let’s identify five key characteristics. Teams:[5]

- share accountability for achieving specific common goals,

- function interdependently,

- require stability,

- hold authority and decision-making power, and

- operate in a social context.

Why Organizations Build Teams

Why do major organizations now rely so much on teams to improve operations? Executives at Xerox have reported that team-based operations are 30 percent more productive than conventional operations. General Mills says that factories organized around team activities are 40 percent more productive than traditionally organized factories. FedEx says that teams reduced service errors (lost packages, incorrect bills) by 13 percent in the first year.[6]

Today it seems obvious that teams can address a variety of challenges in the world of corporate activity. Before we go any further, however, we should remind ourselves that the data we’ve just cited aren’t necessarily definitive. For one thing, they may not be objective—companies are more likely to report successes than failures. As a matter of fact, teams don’t always work. According to one study, team-based projects fail 50–70 percent of the time.[7]

The Effect of Teams on Performance

Research shows that companies build and support teams because of their effect on overall workplace performance, both organizational and individual. If we examine the impact of team-based operations according to a wide range of relevant criteria, we find that overall organizational performance generally improves. Figure 1.2 lists several areas in which we can analyze workplace performance and indicates the percentage of companies that have reported improvements in each area.

| Area of performance | Firms reporting improvement |

|---|---|

| Product and service quality | 70% |

| Customer service | 67% |

| Worker satisfaction | 66% |

| Quality of work life | 63% |

| Productivity | 61% |

| Competitiveness | 50% |

| Profitability | 45% |

| Absenteeism/turnover | 23% |

Figure 1.2: Performance improvements due to team-based operations.

Types of Teams

Teams can improve company and individual performance in a number of areas. Not all teams, however, are formed to achieve the same goals or charged with the same responsibilities. Nor are they organized in the same way. Some, for instance, are more autonomous than others—less accountable to those higher up in the organization. Some depend on a team leader who’s responsible for defining the team’s goals and making sure that its activities are performed effectively. Others are more or less self-governing: though a leader lays out overall goals and strategies, the team itself chooses and manages the methods by which it pursues its goals and implements its strategies.[8] Teams also vary according to their membership. Let’s look at several categories of teams.

Manager-Led Teams

As its name implies, in the manager-led team the manager is the team leader and is in charge of setting team goals, assigning tasks, and monitoring the team’s performance. The individual team members have relatively little autonomy. For example, the key employees of a professional football team (a manager-led team) are highly trained (and highly paid) athletes, but their activities on the field are tightly controlled by a head coach. As team manager, the coach is responsible both for developing the strategies by which the team pursues its goal of winning games and for the outcome of each game and season. They're also solely responsible for interacting with managers above them in the organization. The players are responsible mainly for executing plays.[9]

Self-Managed Teams

Self-managed teams (also known as self-directed teams) have considerable autonomy. They are usually small and often absorb activities that were once performed by traditional supervisors. A manager or team leader may determine overall goals, but the members of the self-managed team control the activities needed to achieve those goals.

Self-managed teams are the organizational hallmark of Whole Foods Market, the largest natural-foods grocer in the United States. Each store is run by 10 departmental teams, and virtually every store employee is a member of a team. Each team has a designated leader and its own performance targets. (Team leaders also belong to a store team, and store-team leaders belong to a regional team.) To do its job, every team has access to the kind of information—including sales and even salary figures—that most companies reserve for traditional managers.[10]

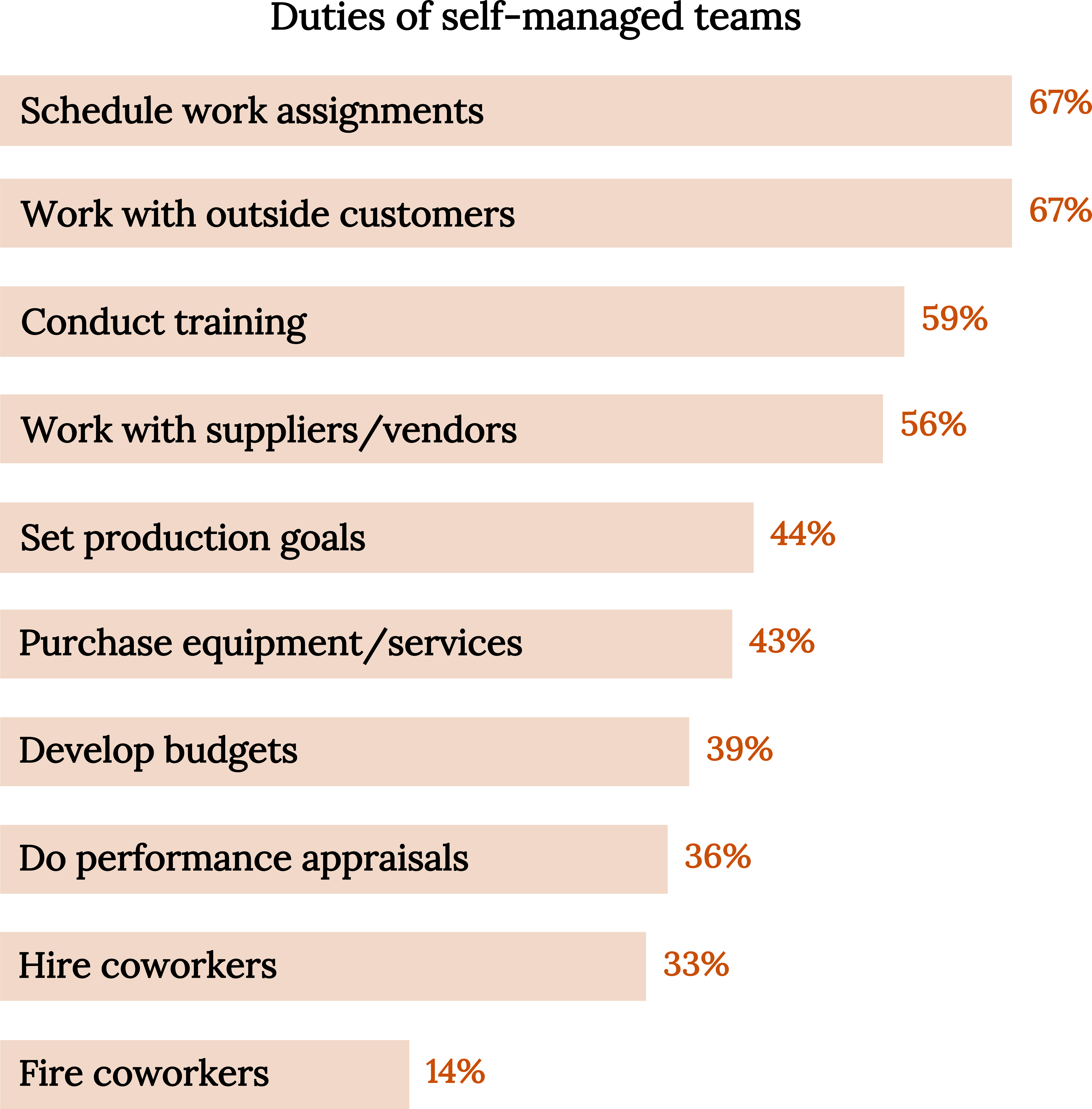

Not every self-managed team enjoys the same degree of autonomy. Companies vary widely in choosing which tasks teams are allowed to manage and which ones are best left to upper-level management only. As you can see in figure 1.4 for example, self-managed teams are often allowed to schedule assignments, but they are rarely allowed to fire coworkers.

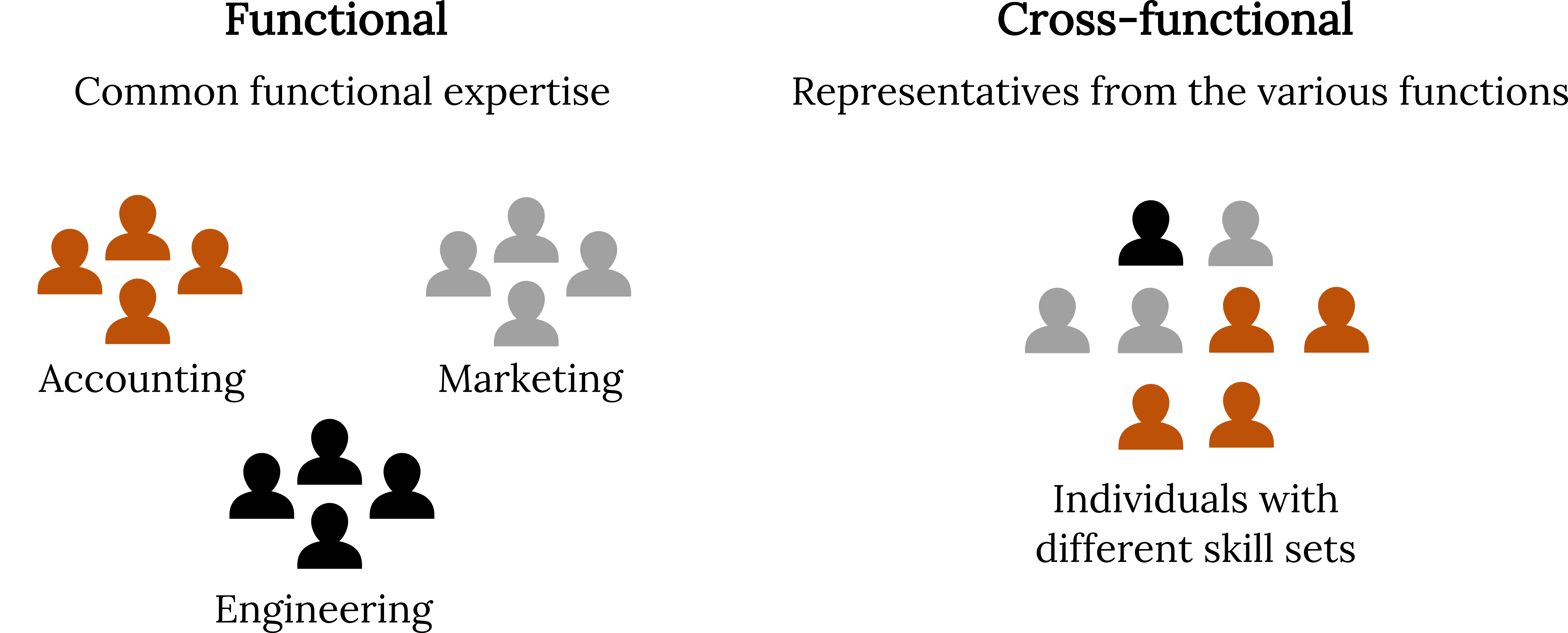

Cross-Functional Teams

Many companies use cross-functional teams—teams that, as the name suggests, cut across an organization’s functional areas (operations, marketing, finance, and so on). A cross-functional team is designed to take advantage of the special expertise of members drawn from different functional areas of the company. For example, when the Internal Revenue Service wanted to study the effects of a major change in information systems on employees, it created a cross-functional team composed of people from a wide range of departments. The final study reflected expertise in such areas as job analysis, training, change management, industrial psychology, and ergonomics.[11]

Cross-functional teams figure prominently in the product-development process at Nike, where they take advantage of expertise from both inside and outside the company. Typically, team members include not only product designers, marketing specialists, and accountants but also sports-research experts, coaches, athletes, and even consumers. Likewise, Motorola’s RAZR team was a cross-functional team; the responsibility for developing the new product wasn’t passed along from the design team to the engineering team, but rather was entrusted to a special team composed of both designers and engineers.

Committees and task forces, both of which are dedicated to specific issues or tasks, are often cross-functional teams. Problem-solving teams, which are created to study such issues as improving quality or reducing waste, may be either intradepartmental or cross-functional.[12]

Virtual Teams

Technology now makes it possible for teams to function not only across organizational boundaries like functional areas, but also across time and space. Technologies such as videoconferencing allow people to interact simultaneously and in real time, offering a number of advantages in conducting the business of a virtual team.[13] Members can participate from any location or at any time of day, and teams can “meet” for as long as it takes to achieve a goal or solve a problem—a few days, weeks, or months. Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, many companies, organizations, governments and learning institutions were forced to move to virtual settings in order to curve the spread of the virus. This transition allowed for continuity of operations as best as possible.

Team size does not seem to be an obstacle when it comes to virtual-team meetings; in building the F-35 Strike Fighter, US defense contractor Lockheed Martin staked the $225 billion project on a virtual product-team of unprecedented global dimension, drawing on designers and engineers from the ranks of eight international partners from Canada, the United Kingdom, Norway, and Turkey.[14]

Why Teamwork Works

Now that we know a little bit about how teams work, we need to ask ourselves why they work. Not surprisingly, this is a fairly complex issue. In this section, we’ll explore why teams are often effective and when they ineffective.

Factors in Effective Teamwork

First, let’s begin by identifying several factors that contribute to effective teamwork. Teams are most effective when the following factors are met:

- Members depend on each other. When team members rely on each other to get the job done, team productivity and efficiency tend to be high.

- Members trust one another.

- Members work better together rather than individually. When team members perform better as a group than alone, collective performance exceeds individual performance.

- Members become boosters. When each member is encouraged by other team members to do his or her best, collective results improve.

- Team members enjoy being on the team.

- Leadership rotates.

Some of these factors may seem intuitive. Because such issues are rarely clear-cut, we need to examine the issue of group effectiveness from another perspective—one that considers the effects of factors that aren’t quite so straightforward.

Group Cohesiveness

The idea of group cohesiveness refers to the attractiveness of a team to its members. If a group is high in cohesiveness, membership is quite satisfying to its members. If it’s low in cohesiveness, members are unhappy with it and may try to leave it.[15]

What Makes a Team Cohesive?

Numerous factors may contribute to team cohesiveness, but in this section, we’ll focus on five of the most important:

- Size. The bigger the team, the less satisfied members tend to be. When teams get too large, members find it harder to interact closely with other members; a few members tend to dominate team activities, and conflict becomes more likely.

- Similarity. People usually get along better with people like themselves, and teams are generally more cohesive when members perceive fellow members as people who share their own attitudes and experience.

- Success. When teams are successful, members are satisfied, and other people are more likely to be attracted to their teams.

- Exclusiveness. The harder it is to get into a group, the happier the people who are already in it. Team status also increases members’ satisfaction.

- Competition. Membership is valued more highly when there is motivation to achieve common goals and outperform other teams.

Maintaining team focus on broad organizational goals is crucial. If members get too wrapped up in immediate team goals, the whole team may lose sight of the larger organizational goals toward which it’s supposed to be working. Let’s look at some factors that can erode team performance.

Groupthink

It’s easy for leaders to direct members toward team goals when members are all on the same page—when there’s a basic willingness to conform to the team’s rules. When there’s too much conformity, however, the group can become ineffective: the group may resist fresh ideas and, even worse, end up adopting its own dysfunctional tendencies as its way of doing things. Such tendencies may also encourage a phenomenon known as groupthink—the tendency to conform to group pressure in making decisions, while failing to think critically or to consider outside influences.

Groupthink is often cited as a factor in the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger in January 1986: engineers from a supplier of components for the rocket booster warned that the launch might be risky because of the weather but were persuaded to set aside their warning by NASA officials who wanted the launch to proceed as scheduled.[16]

Motivation and Frustration

Remember that teams are composed of people, and whatever the roles they happen to be playing at a given time, people are subject to psychological ups and downs. As members of workplace teams, they need motivation, and when motivation is low, so are effectiveness and productivity. The difficulty of maintaining a high level of motivation is the chief cause of frustration among members of teams. As such, it’s also a chief cause of ineffective teamwork, and that’s one reason why more employers now look for the ability to develop and sustain motivation when they’re hiring new managers.[17]

Other Factors that Erode Performance

Let’s take a quick look at three other obstacles to success in introducing teams into an organization:[18]

- Unwillingness to cooperate. Failure to cooperate can occur when members don’t or won’t commit to a common goal or set of activities. What if, for example, half the members of a product-development team want to create a brand-new product and half want to improve an existing product? The entire team may get stuck on this point of contention for weeks or even months. Lack of cooperation between teams can also be problematic to an organization.

- Lack of managerial support. Every team requires organizational resources to achieve its goals, and if management isn’t willing to commit the needed resources— say, funding or key personnel—a team will probably fall short of those goals.

- Failure of managers to delegate authority. Team leaders are often chosen from the ranks of successful supervisors—first-line managers give instructions on a day-to-day basis and expect to have them carried out. This approach to workplace activities may not work very well in leading a team—a position in which success depends on building a consensus and letting people make their own decisions.

The Team and Its Members

“Life Is All About Group Work”

“I’ll work extra hard and do it myself, but please don’t make me have to work in a group.”

Like it or not, you’ve probably already noticed that you’ll have team-based assignments in college. More than two-thirds of all students report having participated in the work of an organized team, and if you’re in business school, you will almost certainly find yourself engaged in team-based activities.[19]

Why do we put so much emphasis on something that, reportedly, makes many students feel anxious and academically drained? Here’s one college student’s practical-minded answer to this question:

“In the real world, you have to work with people. You don’t always know the people you work with, and you don’t always get along with them. Your boss won’t particularly care, and if you can’t get the job done, your job may end up on the line. Life is all about group work, whether we like it or not. And school, in many ways, prepares us for life, including working with others.”[20]

She’s right. In placing so much emphasis on teamwork skills and experience, business colleges are doing the responsible thing—preparing students for the business world. A survey of Fortune 1000 companies reveals that 79 percent use self-managing teams and 91 percent use other forms of employee work groups. Another survey found that the skill that most employers value in new employees is the ability to work in teams.[21] Consider the advice of former Chrysler Chairman Lee Iacocca: “A major reason that capable people fail to advance is that they don’t work well with their colleagues.”[22] The importance of the ability to work in teams was confirmed in a survey of leadership practices of more than sixty of the world’s top organizations.[23]

When top executives in these organizations were asked what causes the careers of high-potential leadership candidates to derail, 60 percent of the organizations cited “inability to work in teams.” Interestingly, only 9 percent attributed the failure of these executives to advance to “lack of technical ability.”

To put it in plain terms, the question is not whether you’ll find yourself working as part of a team. You will. The question is whether you’ll know how to participate successfully in team-based activities.

Will You Make a Good Team Member?

What if your instructor decides to divide the class into teams and assigns each team to develop a new product plus a business plan to get it on the market? What teamwork skills could you bring to the table, and what teamwork skills do you need to improve? Do you possess qualities that might make you a good team leader?

What Skills Does the Team Need?

Sometimes we hear about a sports team made up of mostly average players who win a championship because of coaching genius, flawless teamwork, and superhuman determination.[24] But not terribly often. In fact, we usually hear about such teams simply because they’re newsworthy—exceptions to the rule. Typically a team performs well because its members possess some level of talent. Members’ talents must also be managed in a collective effort to achieve a common goal.

In the final analysis, a team can succeed only if its members provide the skills that need managing. In particular, every team requires some mixture of three sets of skills:

- Technical skills. Because teams must perform certain tasks, they need people with the skills to perform them. For example, if your project calls for a lot of math work, it’s good to have someone with the necessary quantitative skills.

- Decision-making and problem-solving skills. Because every task is subject to problems, and because handling every problem means deciding on the best solution, it’s good to have members who are skilled in identifying problems, evaluating alternative solutions, and deciding on the best options.

- Interpersonal skills. Because teams need direction and motivation and depend on communication, every group benefits from members who know how to listen, provide feedback, and resolve conflict. Some members must also be good at communicating the team’s goals and needs to outsiders.

The key is ultimately to have the right mix of these skills. Remember, too, that no team needs to possess all these skills—never mind the right balance of them—from day one. In many cases, a team gains certain skills only when members volunteer for certain tasks and perfect their skills in the process of performing them. For the same reason, effective teamwork develops over time as team members learn how to handle various team-based tasks. In a sense, teamwork is always work in progress.

What Roles Do Team Members Play?

As a student and later in the workplace, you’ll be a member of a team more often than a leader. Team members can have as much impact on a team’s success as its leaders. A key is the quality of the contributions they make in performing non-leadership roles.[25]

What, exactly, are those roles? At this point, you’ve probably concluded that every team faces two basic challenges:

- Accomplishing its assigned task, and

- Maintaining or improving group cohesiveness.

Whether you affect the team’s work positively or negatively depends on the extent to which you help it or hinder it in meeting these two challenges.[26] We can thus divide teamwork roles into two categories, depending on which of these two challenges each role addresses. These two categories (task-facilitating roles and relationship-building roles) are summarized here:

| Task-facilitating roles | Example | Relationship-building roles | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direction giving | “Jot down a few ideas and we’ll see what everyone has come up with.” | Supporting | “Now, that’s what I mean by a practical application.” |

| Information seeking | “Does anyone know if this is the latest data we have?” | Harmonizing | “Actually, I think you’re both saying pretty much the same thing.” |

| Information giving | “Here are the latest numbers from …” | Tension relieving | “Before we go on, would anyone like a drink?” |

| Elaborating | “I think a good example of what you’re talking about is …” | Confronting | “How does that suggestion relate to the topic that we’re discussing?” |

| Urging | “Let’s try to finish this proposal before we adjourn.” | Energizing | “It’s been a long time since I’ve had this many laughs at a meeting in this department.” |

| Monitoring | “If you’ll take care of the first section, I’ll make sure that we have the second by next week.” | Developing | “If you need some help pulling the data together, let me know.” |

| Process analyzing | “What happened to the energy level in this room?” | Consensus building | “Do we agree on the first four points even if number five needs a little more work?” |

| Reality testing | “Can we make this work and stay within budget?” | Empathizing | “It’s not you. The numbers are confusing.” |

| Enforcing | “We’re getting off track. Let’s try to stay on topic.” | Summarizing | “Before we jump ahead, here’s what we’ve decided so far.” |

Figure 1.8: Team member roles.

Task-facilitating roles

Task-facilitating roles address challenge number one—accomplishing the team goals. As you can see from Table P.6, such roles include not only providing information when someone else needs it but also asking for it when you need it. In addition, it includes monitoring (checking on progress) and enforcing (making sure that team decisions are carried out). Task facilitators are especially valuable when assignments aren’t clear or when progress is too slow.

Relationship-building roles

When you challenge unmotivated behavior or help other team members understand their roles, you’re performing a relationship-building role and addressing challenge number two—maintaining or improving group cohesiveness. This type of role includes activities that improve team “chemistry,” from empathizing to confronting.

Bear in mind three points about this model: (1) Teams are most effective when there’s a good balance between task facilitation and relationship-building; (2) it’s hard for any given member to perform both types of roles, as some people are better at focusing on tasks and others on relationships; and (3) overplaying any facet of any role can easily become counterproductive. For example, elaborating on something may not be the best strategy when the team needs to make a quick decision; and consensus building may cause the team to overlook an important difference of opinion.

Blocking roles

Finally, review figure 1.9, which summarizes a few characteristics of another kind of team-membership role. So-called blocking roles consist of behavior that inhibits either team performance or that of individual members. Every member of the team should know how to recognize blocking behavior. If teams don’t confront dysfunctional members, they can destroy morale, hamper consensus building, create conflict, and hinder progress.

| Blocking behavior | Tactics |

|---|---|

| Dominate | Talk as much as possible; interrupt and interject |

| Overanalyze | Split hairs and belabor every detail |

| Stall | Frustrate efforts to come to conclusions: decline to agree, sidetrack the discussion, rehash old ideas |

| Remain passive | Stay on the fringe; keep interaction to a minimum; wait for others to take on work |

| Overgeneralize | Blow things out of proportion; float unfounded conclusions |

| Find fault | Criticize and withhold credit whenever possible |

| Make premature decisions | Rush to conclusions before goals are set, information is shared, or problems are clarified |

| Present opinions as facts | Refuse to seek factual support for ideas that you personally favor |

| Reject | Object to ideas by people who tend to disagree with you |

| Pull rank | Use status or title to push through ideas, rather than seek consensus on their value |

| Resist | Throw up roadblocks to progress; look on the negative side |

| Deflect | Refuse to stay on topic; focus on minor points rather than main points |

Figure 1.9: Types and examples of blocking behaviors.

Class Team Projects

In your academic career you’ll participate in a number of team projects. To get insider advice on how to succeed on team projects in college, let’s look at some suggestions offered by students who have gone through this experience.[27]

- Draw up a team charter. At the beginning of the project, draw up a team charter that includes: the goals of the group; ways to ensure that each team member’s ideas are considered; timing and frequency of meeting. A more informal way to arrive at a team charter is to simply set some ground rules to which everyone agrees.

- Contribute your ideas. Share your ideas with your group. The worst that could happen is that they won’t be used (which is what would happen if you kept quiet).

- Never miss a meeting or deadline. Pick a weekly meeting time and write it into your schedule as if it were a class. Never skip it.

- Be considerate of each other. Be patient, listen to everyone, involve everyone in decision making, avoid infighting, build trust.

- Create a process for resolving conflict. Do so before conflict arises. Set up rules to help the group decide how conflict will be handled.

- Use the strengths of each team member. All students bring different strengths. Utilize the unique value of each person.

- Don’t do all the work yourself. Work with your team to get the work done. The project output is often less important than the experience.

What Does It Take to Lead a Team?

To borrow from Shakespeare, “Some people are born leaders, some achieve leadership, and some have leadership thrust upon them.” At some point in a successful career, you will likely be asked to lead a team. What will you have to do to succeed as a leader?

Like so many of the questions that we ask in this book, this question doesn’t have any simple answers. We can provide one broad answer: A leader must help members develop the attitudes and behavior that contribute to team success: interdependence, collective responsibility, shared commitment, and so forth.

Team leaders must be able to influence their team members. Notice that we say influence: except in unusual circumstances, giving commands and controlling everything directly doesn’t work very well.[28] As one team of researchers puts it, team leaders are more effective when they work with members rather than on them.[29] Hand-in-hand with the ability to influence is the ability to gain and keep the trust of team members. People aren’t likely to be influenced by a leader whom they perceive as dishonest or selfishly motivated.

Assuming you were asked to lead a team, there are certain leadership skills and behaviors that would help you influence your team members and build trust. Let’s look briefly at some of them:

- Demonstrate integrity. Do what you say you’ll do and act in accordance with your stated values. Be honest in communicating and follow through on promises.

- Be clear and consistent. Let members know that you’re certain about what you want and remember that being clear and consistent reinforces your credibility.

- Generate positive energy. Be optimistic and compliment team members. Recognize their progress and success.

- Acknowledge common points of view. Even if you’re about to propose some kind of change, recognize the value of the views that members already hold in common.

- Manage agreement and disagreement. When members agree with you, confirm your shared point of view. When they disagree, acknowledge both sides of the issue and support your own with strong, clearly-presented evidence.

- Encourage and coach. Buoy up members when they run into new and uncertain situations and when success depends on their performing at a high level.

- Share information. Give members the information they need and let them know that you’re knowledgeable about team tasks and individual talents. Check with team members regularly to find out what they’re doing and how the job is progressing.

Key Takeaways

- A team (or a work team) is a group of people with complementary skills and diverse areas of expertise who work together to achieve a specific goal.

- Work teams have five key characteristics. They are accountable for achieving specific common goals. They function interdependently. They are stable. They have authority. And they operate in a social context.

- Work teams may be of several types:

- In the traditional manager-led team, the leader defines the team’s goals and activities and is responsible for its achieving its assigned goals.

- The leader of a self-managed team may determine overall goals, but employees control the activities needed to meet them.

- A cross-functional team is designed to take advantage of the special expertise of members drawn from different functional areas of the company.

- On virtual teams, geographically dispersed members interact electronically in the process of pursuing a common goal.

- Group cohesiveness refers to the attractiveness of a team to its members. If a group is high in cohesiveness, membership is quite satisfying to its members; if it’s low in cohesiveness, members are unhappy with it and may even try to leave it.

- As the business world depends more and more on teamwork, it’s increasingly important for incoming members of the workforce to develop skills and experience in team-based activities.

- Every team requires some mixture of three skill sets:

- Technical skills: skills needed to perform specific tasks

- Decision-making and problem-solving skills: skills needed to identify problems, evaluate alternative solutions, and decide on the best options

- Interpersonal skills: skills in listening, providing feedback, and resolving conflict

References

Figures

Figure 1.1: Woman on the phone. Good Faces. 2021. Unsplash license. https://unsplash.com/photos/lY8ZoxeGUhU.

Figure 1.2: Performance improvements due to team-based operations. Adapted from Edward E. Lawler, S. A. Mohman, and G. E. Ledford (1992). Creating High Performance Organizations: Practices and Results of Employee Involvement and Total Quality in Fortune 1000 Companies. San Francisco: Wiley. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Figure 1.3: Virginia Tech head football coach, Brent Pry. SneakinDeacon. 2021. CC BY-SA 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/2mP1fd6.

Figure 1.4: Duties of self-managed teams. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0. https://archive.org/details/1.5_20220621.

Figure 1.5: Cross-functional teams. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0. Added person by Richa from Noun Project (Noun Project license). https://archive.org/details/1.6_20220621.

Figure 1.6: The space shuttle Challenger’s first launch in 1983. U.S. federal government. 1983. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Space_Shuttle_Challenger_(04-04-1983).JPEG.

Figure 1.7: Teamwork makes the dream work! Ivan Samkov. 2021. Pexels license. https://www.pexels.com/photo/coworkers-looking-at-a-laptop-in-an-office-8127690/.

Figure 1.8: Team member roles. Adapted from David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron (2007). Developing Management Skills, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. Pp. 517, 519.

Figure 1.9: Types and examples of blocking behaviors. Adapted from David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron (2007). Developing Management Skills, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. Pp. 519-20.

- The Motorola vignette is based on the following sources: Adam Lashinsky (2006). “RAZR’s Edge.” Fortune. Retrieved from: http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2006/06/12/8379239/index.htm; Scott D. Anthony (2005). “Motorola’s Bet on the RAZR’s Edge.” HBS Working Knowledge. Retrieved from: http://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/4992.html; Roger O. Crockett (2005). “The Leading Edge is RAZR-Thin.” Bloomberg. Retrieved from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2005-12-04/the-leading-edge-is-razr-thin; Arik Hessedahl (2004). “Motorola vs. Nokia.” Forbes.com. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/2004/01/19/cx_ah_0119mondaymatchup.html; Vlad Balan (2007). “10 Coolest Concept Phones Out There.” Cameraphones Plaza. Retrieved from: http://www.cameraphonesplaza.com/10-coolest-concept-phones-out-there/. ↵

- Roger O. Crockett (2005). “The Leading Edge is RAZR-Thin.” Bloomberg. Retrieved from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2005-12-04/the-leading-edge-is-razr-thin ↵

- This section is based in part on Leigh L. Thompson (2008). Making the Team: A Guide for Managers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 4. ↵

- Wilderdom.com (2006). “Team Building Quotes.” Retrieved from: http://www.wilderdom.com/teambuilding/Quotes.html ↵

- Adapted from Leigh L. Thompson (2008). Making the Team: A Guide for Managers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 4-5; C. P. Alderfer (1977). “Group and Intergroup Relations,” in Improving Life at Work. J. R. Hackman and J. L. Suttle ed. (1977). Palisades, CA: Goodyear. pp. 277–96. ↵

- Kimball Fisher (1999). Leading Self-Directed Work Teams: A Guide to Developing New Team Leadership Skills, rev. ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; Jerald Greenberg and Robert A. Baron (2008). Behavior in Organizations, 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 315–16. ↵

- Jerald Greenberg and Robert A. Baron (2008). Behavior in Organizations, 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 316; Leigh L. Thompson (2008). Making the Team: A Guide for Managers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 5. ↵

- Leigh L. Thompson (2008). Making the Team: A Guide for Managers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 8-13. ↵

- Ibid. p. 9 ↵

- Charles Fishman (1996). “Whole Foods Is All Teams.” Fast Company. Retrieved from: http://www.fastcompany.com/26671/whole-foods-all-teams ↵

- Human Resources Development Council (n.d.). “Organizational Learning Strategies: Cross-Functional Teams.” Getting Results through Learning. Retrieved from: http://www.humtech.com/ForestService/sites/GRTL/ols/ols3.htm ↵

- Stephen P. Robbins and Timothy A. Judge (2009). Organizational Behavior, 13th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 340–42. ↵

- Jennifer M. George and Gareth R. Jones (2008). Understanding and Managing Organizational Behavior, 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 381–82. ↵

- Adept Scientific (n.d.). “Lockheed Martin Chooses Mathcad as a Standard Design Package for F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Project.” Retrieved from: http://www.adeptscience.co.uk/media-room/press_room/lockheed-martin-chooses-mathcad-as-a-standard-design-package-for-f-35-joint-strike-fighter-project.html ↵

- This section based on: David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron (2007). Developing Management Skills, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 497. ↵

- John Schwartz and Matthew L. Wald (2003). “The Nation: NASA's Curse? 'Groupthink' Is 30 Years Old, And Still Going Strong.” New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/09/weekinreview/the-nation-nasa-s-curse-groupthink-is-30-years-old-and-still-going-strong.html ↵

- This section is based on Jerald Greenberg and Robert A. Baron (2008). Behavior in Organizations, 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 317–18. ↵

- Leigh L. Thompson (2008). Making the Team: A Guide for Managers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 323-324. ↵

- David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron (1991). Developing Management Skills, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 498–99; Richard S. Wellins, William C. Byham, and Jeanne M. Wilson (1991). Empowered Teams. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ↵

- Lauren Elrick (2015). “The Importance of Teamwork Skills in Work and School.” Rasmussen College, College Life Blog. Retrieved from: http://www.rasmussen.edu/student-life/blogs/college-life/importance-of-teamwork-skills-in-work-and-school/ ↵

- David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron (1991). Developing Management Skills, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 498-499; Edward E. Lawler (2003). Treat People Right. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ↵

- Lee Iacocca and William Novak (2007). Iacocca. New York: Bantam. p. 61. ↵

- The Hay Group (1999). "What Makes Great Leaders: Rethinking the Route to Effective Leadership: Findings from the Fortune Magazine/Hay Group 1999 Executive Survey of Leadership Effectiveness.” Retrieved from: http://www.lrhartley.com/seminars//great-leaders.pdf ↵

- Stephen P. Robbins and Timothy A. Judge (2009). Organizational Behavior, 13th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 346-7. ↵

- David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron (1991). Developing Management Skills, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 516-520. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Kristen Feenstra (n.d.). “Study Skills: Teamwork Skills for Group Projects.” Powertochange.com. Retrieved from: http://powertochange.com/students/academics/groupproject/ ↵

- David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron (1991). Developing Management Skills, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 520. ↵

- Kristen Feenstra (n.d.). “Study Skills: Teamwork Skills for Group Projects.” Powertochange.com. Retrieved from: http://powertochange.com/students/academics/groupproject/ ↵