6 Lung Cancer

Learning objectives

- Describe the four major categories of primary lung cancer and the associated risk factors.

- Describe the clinical manifestations of lung cancer.

This chapter will deal with only primary lung cancer (i.e., that originating in the lung), although many other forms of cancer that originate outside of the lung commonly metastasize to the pulmonary system. By far the most common site of malignant neoplasm is the bronchial mucosa and so it is referred to as bronchogenic carcinoma. Most cases are related to smoking, and the risk of bronchogenic carcinoma is related to the duration and intensity of smoking—two packs a day for twenty years increases risk of lung cancer seventy times above a nonsmoker’s risk. Other environmental or occupational factors can play a role, and when compounded with smoking the effect on risk can be multiplicative rather than additive, similar to asbestos exposure.

About half of neoplasms arise centrally, while the other half have a more peripheral origin in the smaller airways; but this is often very difficult to ascertain in advanced disease. The upper lobes are more commonly involved, particularly in the anterior segments, and the right lobe is more commonly involved than the left.

Four major types of bronchogenic carcinoma can be distinguished by histology, epidemiology, clinical features, and prognosis. They are:

- squamous cell,

- adenocarcinoma,

- large cell, and

- small cell.

Let us look at the features of each.

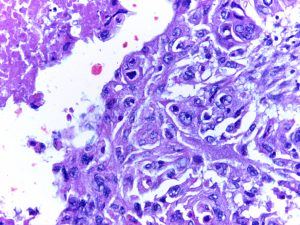

Squamous Cell

Squamous cell cancer accounts for about one-third of all lung cancers and is more common in men. It is pathologically characterized by keratin formation between cells and the development of large, well-outlined islands of cancer cells. It is usually centrally located and associated with the main bronchi. Metastasis tends to be local, affecting the surrounding areas and lymph nodes.

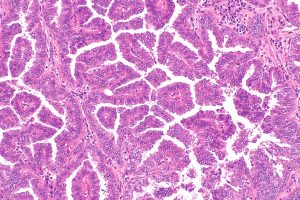

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma also accounts for about one-third of cases but is the most common lung cancer in women. The lesion has a glandular structure and may produce mucin. This is usually a peripheral lesion and distant metastasis is common.

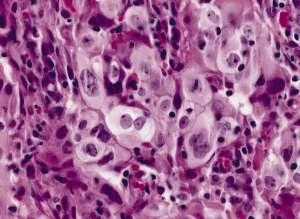

Large Cell

Large cell is less common and is seen in about 10 percent of cases, most of whom are male. The diagnosis is made by cell size, which is large and easily distinguished from squamous cell cancer or adenocarcinoma. The lesions can be anywhere in the lung but are often found in the periphery. This is a fast-growing cancer and so is frequently diagnosed at a later disease stage.

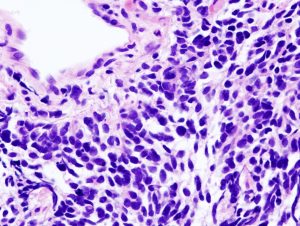

Small Cell

The previous three types of cancer are collectively known as non-small cell lung cancer. Alternatively, small cell cancer is found in about 15 percent of cases. It is less predominant in men, and incidence in women is rising. The small cells have an oat-like appearance, and the most common small cell cancer is known as oat cell carcinoma and the lesions frequently have endocrine function. Originating in the main bronchi this cancer spreads very quickly into other thoracic and extrathoracic sites, and this form carries a very poor prognosis.

The characteristics of these forms of lung cancer are summarized in table 6.1.

| Squamous cell | Adenocarcinoma | Large cell | Small cell |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~33% of cases | ~33% of cases | ~10% of cases | ~10–15% of cases |

| More common in men | More common in women | Mostly found in men | Increasing rate in women |

|

|

|

|

| Keratin bridges between cells | Glandular architecture (may produce mucin) | Diagnosis made by size of cells | Oat-like appearance, endocrine function |

| Islands of cancer cells | Distant metastasis is common | Fast growing, often diagnosed as established disease | Highly malignant, rapid, and widespread metastasis |

| Most centrally located around main bronchi and affect local tissue | Frequently a peripheral lesion | Can be anywhere in the lung but more often peripheral | Starts in main bronchi but rapidly spreads |

Table 6.1: Summary of forms of lung cancer.

Clinical Signs

The signs and symptoms can be variable and diverse depending on the location, type, size, and rapidity of growth. Patients may even be asymptomatic when the lesion is found on chest x-ray or with bronchoscope.

The most common symptom is cough, but unfortunately the patient, likely being a smoker, may be accustomed to cough and not think anything of it. Bloody sputum occurs in only about half of patients and is a frequent cause for them seeking medical advice, and severe hemoptysis is uncommon.

Chest pain is fairly common and ranges from a mild ache or feeling of heaviness, to severe and unremitting. Pain does not necessarily indicate pleural or chest wall involvement, although significant steady pain is more indicative of this complication.

Dyspnea may arise as the tumor obstructs a major airway or causes a large pleural effusion, but it can also be due to underlying bronchopulmonary disease.

Physical exam is likely to be normal in the early stages of the disease, but as the cancer progresses the exam usually reveals signs associated with either bronchial obstruction or a consequence of metastasis. Bronchial obstruction can lead to wheeze or other modified breath sounds, atelectasis, down-stream pneumonia, or pleural effusion. Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with the cancer can cause disruption to other systems and lead to characteristic weight loss, muscle wasting, and digital clubbing.

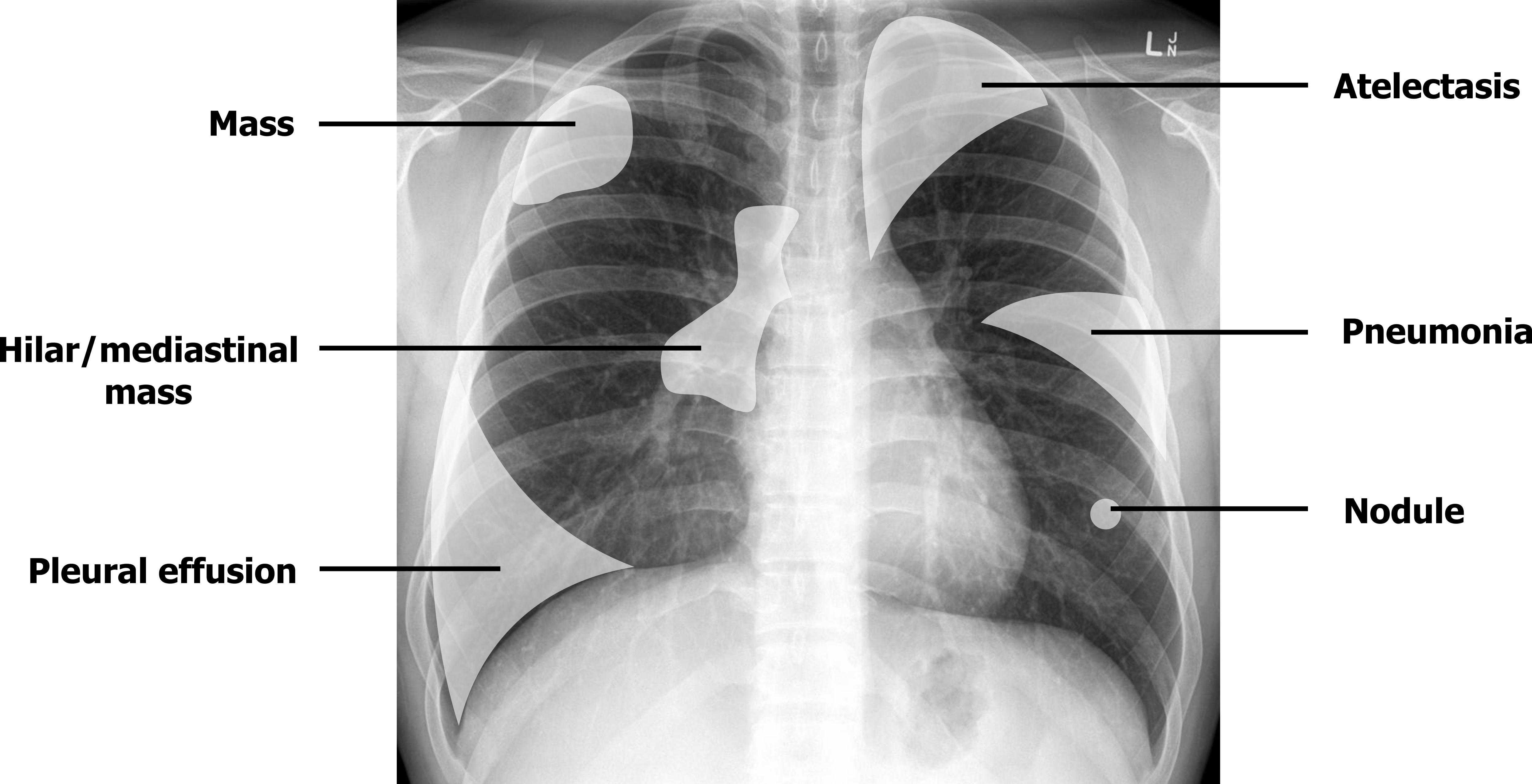

Chest x-ray is usually only capable of detecting advanced cancer stages, and therefore is not the best screening tool. Low-dose CT screening can be used to detect early stages of disease before symptoms arise and is advised for patients between fifty to eighty years old with a twenty-pack-per-year smoking history or who have quit smoking in the past fifteen years. Once the disease is established, however, the x-ray’s findings can either be direct detection of a mass, or a secondary consequence of the mass; therefore they are quite variable (figure 6.1).

- A mass may show as a solitary nodule or coin lesion, and peripheral lesions are most commonly associated with adenocarcinoma.

- Invasion of the tumor to lymph nodes may be observed as a hilar or mediastinal mass and is common with small cell carcinoma.

- Large cell cancer is frequently associated with large peripheral masses that may cavitate.

- Squamous cell carcinoma is frequently associated with bronchial obstruction, so as well as being detected as a mass it (and the other forms of cancer) can lead to detectable secondary effects such as atelectasis or a pneumonia that persistently appears in the same location. Pleural effusions, which can be massive, are sometimes the radiographic manifestation of lung cancer.

- Thoracic CT imaging is more useful for delineation of the original lesion and is now routinely used as a screening tool for current or ex-smokers.

References, Resources, and Further Reading

Text

Farzan, Sattar, with Doris L. Hunsinger and Mary L. Phillips. “Chapter 20.” In A Concise Handbook of Respiratory Diseases. Reston, VA: Reston Publishing Company, 1978.

Husain, Aliya N. “Chapter 15: The Lung.” In Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 9th ed., edited by Vinay Kumar, Abul K. Abbas, and John C. Aster. Philadelphia: Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., 2015.

Figures

Table 6.1: Summary of forms of lung cancer. Includes Squamous Cell Carcinoma Lung 40x by Calicut Medical College from WikimediaCommons (CC BY-SA 4.0), Papillary adenocarcinoma of the lung — intermed mag by Nephron from WikimediaCommons (CC BY-SA 3.0), Large cell carcinoma of the lung by The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) from WikimediaCommons (Public domain), and Lung small cell carcinoma (1) by core needle biopsy by KGH from WikimediaCommons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Figure 6.1: Potential radiographic findings in lung cancer. Grey, Kindred. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Includes Normal frontal chest x-ray by Gaillard, F., et al. from https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-8090 (labels and shaded areas added) (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0). https://archive.org/details/6.2_20220203