6 Public Aquariums and Their Role in Education, Science, and Conservation

Learning Objectives

- Explain the conservation mandate of public aquariums for research, conservation outreach, policy, and education.

- Summarize the motivational factors of visitors to public aquariums.

- Articulate the potential affects that visitation to public aquariums has on visitors.

- Describe new initiatives to propagate rare and endangered fish in partnerships with public aquariums.

- Examine the future challenges for public aquarium management.

6.1 Role of Public Aquariums

Public aquariums[1] are special places for people to learn about aquatic life. The number of public aquariums has grown since the opening of the first in Regent’s Park, London, in 1853 (Hillard 1995). Early aquariums were devoted to game fish and were auxiliary locations for hatchery-reared fish. Public aquariums have four aims today—aesthetic, educational, entertainment, and scientific—while introducing many people to fish, their adaptations, habitats, values, and human uses. Expansion of aquariums in many large urban centers was intended to enhance tourism and promote an “Age of Aquariums” (Murr 1988). Broad-based community support and high visitation rates make public aquariums among some of the most important places for public engagement in fish conservation to begin. More than 700 million people visited zoos and aquariums worldwide in 2008 (Gusset and Dick 2010). In the United States alone, over 183 million people visit zoos and aquariums annually—this is three times the number of recreational anglers in the country.

The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums defines conservation as “securing populations of species in natural habitats for the long term” (Barongi et al. 2015). As you read more about the roles and challenges of public aquariums, you should envision the future potential for public aquariums to become even more influential in fish conservation programs. Public aquariums strive to communicate the issues, raise awareness, change behaviors, and gain widespread public and political support for conservation actions (Reid et al. 2013). Aquariums are often the first place where aspiring young conservation champions are first exposed to aquatic animals. For example, pioneering ichthyologist Dr. Eugenie Clark first visited the New York Aquarium at age nine (Clark 1951).

Large public aquariums are accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Accreditation is a process by which the aquarium is evaluated by experienced and trained experts in operations, animal welfare and husbandry, and veterinary medicine and is measured against the established standards and best practices of aquarium management. In accredited aquariums, the behavioral and physical needs of animals are being met by providing opportunities for species-appropriate behaviors and choices. Consequently, a reliable way to choose an aquarium for visitation is to look for the notice, “Accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.”

6.2 Education and Interpretation

Education and interpretation are both on-site and off-site programs for targeted audiences, such as school groups, teachers, and families. Educational programs are proven methods for increasing awareness and participation in aquatic conservation. Conservation education programs are designed to fulfill specific goals of each institution. Many types of interpretive methods may be employed, but they typically involve graphic and video displays, exhibits of live animals, ambassador animals, and talks by animal care and conservation specialists.

At a time when fish conservation needs are acute in marine and freshwaters, the tensions and tradeoffs are apparent for aquarium conservation programs. Animal welfare concerns must be balanced against educational values of displays (Maynard 2018). Built aquatic habitats vary greatly in their suitability for fish. Consequently, the displays offer the potential to explain unique requirements of the displayed animals. Increasingly, video displays have emerged for education that can be delivered at aquariums as well as online. For example, Shark Cams (explore.org) installed around the world provide a view of sharks in their underwater world.

While shark displays are very popular in public aquariums, they may invoke controversies. Some aquarium goers prefer sharks with a predatory appearance, with streamlined bodies that display strong swimming ability. These include Blacktip Shark, Grey Reef Shark, and Sandbar Shark. Such shark displays require enormous tanks and skilled and experienced caretakers who use feeding tongs to ensure proper nutrition, thereby minimizing sharks eating their tank mates. Large sharks are difficult to capture and transport from the wild to aquariums. Sharks have declined in many parts of the world (Dulvy et al. 2014), and displays must convey a strong conservation message to justify their captivity. Other sharks, such as the Zebra Sharks, nurse sharks, carpet sharks, and other skates and rays more readily adapt to life in captivity.

Ambassador animals provide a powerful catalyst for learning. These are select animals whose role includes handling and/or training by staff or volunteers for interaction with the public and in support of institutional education and conservation goals. They allow the public to observe and interact with an animal that they may never see otherwise (Spooner et al. 2021). Ambassadors are important advocates for the protection of habitats and animals in nature.

In the 1930s, the John G. Shedd Aquarium in Chicago displayed a Smalltooth Sawfish (Pristis pectinata, Figure 6.1) for the first time. Since that time, other public aquariums have connected visitors with these unique and endangered fish. Millions of visitors have enjoyed the experience of seeing a sawfish up close and wondering about their existence in the wild. Worldwide, the sawfish and rays are among the most endangered fish. The educational displays of sawfish create a common understanding of their plight as the first step in a multifaceted approach needed to conserve populations of sawfish.

In an age where children lack nature experiences, public aquariums, by providing access to live animals in natural-like settings, enable human-fish relationships to be developed (Miller 2004; Louv 2008; Bekoff 2014; Brown 2015). Visitation at public aquariums allows thoughtful people to build a common definition of the conservation problem and understanding of the essential planning process.

The education and interpretation missions are undoubtedly the most important. They connect people to animals that they may never see otherwise, and that connection is important in developing advocacy for protection of habitats and animals in nature. To expand their education impact, public aquarium staff often collaborate with community groups, school districts, local colleges, and universities to expand the reach of education and interpretation programs.

6.3 Connecting Aquarium Visitors to Biodiversity Conservation

How do we motivate people who do not fish to care about aquatic life? Millennials, people born between 1981 and 1997, are more likely to be concerned with animal welfare issues than environmental protection (Palmer et al. 2018). Millennials are also more likely to believe in individuals as the source of solutions and trust less in the effectiveness of governments or nongovernmental organizations (Dropkin et al. 2015). Public support for conservation depends on committed and engaged conservationists who work for or with public aquariums. Their actions flow from acceptance of wildlife values, beliefs that fish are under threat, and beliefs that personal actions can help alleviate the threat and restore values. Self-interest, altruism toward other humans, and altruism toward other species and the biosphere are value orientations linked to pro-environmental behavior (Stern et al. 1999). People can be subtly influenced to change their behavior (i.e., nudged) by using seemingly innocuous persuasion (Thaler and Sunstein 2008). Committed individuals move conservation forward via pro-environmental behavior, often in the face of inertial and active resistance (Ballantyne and Packer 2016).

All members of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums have a goal of creating a strong connection between their resident animals and their counterparts in nature and integrated species conservation plans (Barongi et al. 2015). The educated public expects a strong conservation message from public aquariums. Some of the best public aquariums have dynamic educational programs as well as collaborative in situ conservation programs (Knapp 2018). Public aquariums train and support staff in accurately evaluating educational benefits of visitation via questionnaires and interviews (Falk et al. 2007; Marino et al. 2010; Mellish et al. 2019). Understanding and knowledge of biodiversity loss significantly increased after visits relative to previsit levels (Moss et al. 2015).

But do aquariums influence conservation actions? Empathy for the plight of animals is an emotional capacity that develops over time and is reinforced through interactions (Fennel 2012). Empathy relies on the ability to perceive, understand, and care about the experiences or perspectives of another person or animal. Empathy, an internal motivator toward acting, is elicited more by exposure to primates, elephants, and canines than to fish. Fish lack facial expressions and other cues for human empathy (Myers 2007; Webber et al. 2017). Motivating visitors to take action is a complex interplay among barriers, incentives, affective outcomes, and internal motivators (Young et al. 2018). Research studies support the idea that people who establish personal connections with nature are likely to value and protect elements of natural environments. Public aquariums play an essential role in providing opportunities for people to connect to fish and aquatic life and learn to care about conservation. Positive messaging, rather warnings about a coming apocalypse, are more likely to result in support for conservation actions (Jacobson et al. 2019).

Questions to ponder:

The following quote by Baba Dioum is often used in communications about conservation:

“In the end we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.” Baba Dioum (1986, cited in Valenti et al. 2005)

Do you agree or disagree with this sentiment? What type of information is most relevant to you in supporting conservation practices?

6.4 Restorative Nature of Public Aquariums

Public aquariums are popular tourist attractions and are interested in the guests’ motivations and experiences. Many are interested in whether an aquarium visit provides humans benefits in terms of psychological well-being or relaxation. Humans benefit from interactions with companion animals, primarily cats and dogs. If you ever had a pet dog, you know dogs can relieve a sense of loneliness. Dogs seem to know when you are feeling down and provide emotional support. Studies show that interactions with nonhuman animals lowered blood pressure and reduced risk of heart disease (Levine et al. 2013; Stanley et al. 2014; Mubanga et al. 2017; Brooks et al. 2018). Is it possible our interactions with pets can lead to longer life spans? A review paper published by the American Heart Association concluded that (1) pet ownership, particularly dog ownership, may be reasonable for reduction in risk of cardiovascular disease; and (2) pet adoption, rescue, or purchase should not be done for the primary purpose of reducing risk of cardiovascular disease (Levine et al. 2013). The association of pet ownership and regular aerobic activity is likely related to the effects. Although the “pet effect” on physical and mental health remains a hypothesis that is routinely debated, therapeutic interventions with animals continue to be practiced.

Few systematic studies have measured the benefits of fish viewing. Those who keep fish as pets find that it provides purpose and enjoyment in life (Langfield and James 2009). Early observations in medical facilities suggested a link between viewing fish in aquariums and benefits such as reduced blood pressure and increased relaxation (Riddick 1985). In controlled, experimental settings, fish viewing improved mood and reduced anxiety (Wells 2005; Gee et al. 2019). In some cases, fish viewing reduced stress and anxiety in patients (Cracknell et al. 2018; Clements et al. 2019). It is difficult to design a study of the psychological or physiological responses of visitors to public aquariums because of the difficulty of isolating causal factors, such as what exhibits were viewed or the effects of social interactions during the aquarium visit. However, there are enough indications that aquarium visiting has a calming effect (Cracknell et al. 2018; Clements et al. 2019) to support the argument that biodiversity in aquariums may influence well-being outcomes for the visitors.

Questions to ponder:

Can you remember a visit to a public aquarium? In what ways were you affected by the visit? Can you describe the type of exhibit or experience that was most memorable? Does it matter to the visitors that the displays at public aquariums are built and not natural?

6.5 Conservation and Public Aquariums

The larger and more progressive public aquariums are expanding their missions and conservation portfolios to align with the World Zoo and Aquarium (WZ Conservation Strategy (Barongi et al. (2015), which calls for a more action-driven, field-based conservation. Many responsibilities are outlined here:

- Provide the highest-quality care and management of wildlife within and across institutions.

- Develop and adapt intensive wildlife-management techniques for use in protecting and preserving species in nature.

- Support conservation-directed social and biological research.

- Lead, support, and collaborate with education programs that target changes in community behavior toward better outcomes for conservation.

- Use zoological facilities to provide for populations of species most in need of genetic and demographic support for their continued existence in the wild.

- Promote and exemplify sustainable practices in the management of animal populations, our facilities, and the environment.

- Provide a public arena to discuss and debate the challenges facing society as extinction accelerates and ecosystem services are degraded.

- Act as rescue-and-release centers for threatened animals in need of immediate help, with the best knowledge and facilities to care for them until they are fit to go back to the wild.

- Be major contributors of intellectual and financial resources to field conservation.

- Provide ethical and moral leadership.

In 2014, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums developed a common approach for expanding the scope of field conservation called Saving Animals from Extinction (SAFE). The mission of SAFE is to “combine the power of zoo and aquarium visitors with the resources and collective expertise of AZA members and partners to save animals from extinction.” This mission is achievable because accredited zoos and aquariums are uniquely positioned to become a force for global conservation, with more scientists, more animals, and more ability to activate the public than any other nongovernmental institution. SAFE is built on aquarium and zoo’s 100-year track record of success in saving endangered species from extinction. SAFE uses the One Plan Approach, where management strategies and conservation actions are developed by those with responsibilities for all populations (Grow et al. 2018). Priorities for selecting conservation projects depend on location, expertise, collection composition, institutional culture, financial restrictions, and collaboration with stakeholders (Knapp 2018). Sharks and rays—which are decreasing at alarming rates along with many critically endangered species and lack sustainable captive populations—were the first group of fish to be selected for applying the AZA SAFE approach. Seattle Aquarium, Shark Trust, Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium, North Carolina Aquariums, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and many others collaborate to leverage the large audiences of public aquariums to increase awareness.

In some cases, public aquariums have dedicated research institutes to lead research efforts. For example, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute is a world leader in deep-ocean science and technology and uses novel tools to monitor ocean change, carbon emissions, and harmful algal blooms. Public aquariums with a long history of focusing on discoveries have been instrumental in supporting explorers and scientists. Consider the inspirational story of Eugenie Clark, who became a world authority on sharks and fish and founded the Mote Marine Lab (Rutger 2015), which later added a public aquarium. Eugenie Clark’s first exposures to marine life, as noted earlier, were at the New York Aquarium at age nine. She made the first groundbreaking discovery that sharks could be trained to learn visual tasks as fast as some mammals, and she left a long legacy of shark research.

Large public aquariums are engaged in numerous partnerships for conservation. These partnerships require trust, a key driver for effective collaborations, conflict resolution, and performance in implementing conservation (Ostrom 2003; Fulmer and Gelfand 2012). Nonscientists form public opinions about conservation policy issues and rely on many sources. Scientific knowledge is only one source, but it enables citizens to engage in political decisions. Public aquariums, through their combined mission of conservation science and education, are a trusted source of science information and work on fish conservation through many partnerships (Rank 2018; Huber et al. 2019).

Many public aquariums also work to restore degraded local habitats and support ecosystem health. In these actions, they must partner with local volunteers in nearby waters, parks, forests, and preserves. Public aquariums in large urban centers work to install treatments that help reverse effects of polluted stormwater runoff for impervious surfaces, storm drains, cracked pipes, and more. The National Aquarium in Baltimore, Maryland, and the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, Illinois, are installing floating wetlands to treat excess nitrogen and create fish habitat in the local waters. The plants on the wetlands grow hydroponically and take up nutrients directly from the water before they cause harmful algal blooms. In these highly modified, urban waters, the floating wetlands are planted with native plants and attract a variety of native species. The floating wetland prototype designed by the National Aquarium was recognized by the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Larger public aquariums, including the New England Aquarium, Monterey Bay Aquarium, and Shedd Aquarium, are global leaders in outreach and use a portion of their budgets to fund larger programs. Shedd Aquarium has focused on charismatic flagship species, such as seahorses, sharks, and Nassau Grouper in The Bahamas, Arapaima in Guyana, as well as less well-known species, such as Queen Conch in the Caribbean and suckers in the Great Lakes. These outreach programs follow naturally from a vibrant research program focused on marine species (corals, Queen Conch, Nassau Grouper, sharks, and rays) and freshwater species (amphibians, freshwater mussels, and a diverse array of Great Lakes fish).

The public aquariums have scientific expertise on their staffs that give these conservation initiatives strong scientific grounding. A recent decline in favorability toward zoos and aquariums (Bergl 2017) may suggest a concomitant decline in trust; however, there are numerous examples of productive fish conservation programs emanating from public aquariums. Some public aquariums have research in their mission statements and support their staff to do research with direct conservation benefits (Knapp 2018; Loh et al. 2018). Consequently, you will find public aquariums playing an essential role as a trusted resource on fish conservation partnerships throughout the world. Collaborative programs include numerous partnerships. For example, the World Fish Migration Day raises global awareness about free-flowing rivers and migratory fish. Global FinPrint unites collaborators around the world to study sharks, rays, and other marine life with baited remote underwater video.

Question to ponder:

Can you imagine ways in which aquarium visitation leads to the appreciation and conservation of the natural environments and life therein?

6.6 Partnerships to Propagate and Restore Rare Fish and Habitats

On any visit to a large public aquarium, you will learn about efforts to propagate and restore rare fish. You may even be able to view rare or extinct in the wild fish. Currently, aquariums hold four of the six fish species listed by the IUCN Red List as “Extinct in the Wild.” (Table 6.1; da Silva et al. 2019). Public aquariums often keep and breed threatened species in captivity until such time as suitable conditions exist for reintroduction to the wild. Many other species with conservation value are held and, in some cases, propagated by public aquariums. In fact, 9.3% of ray-finned fish species, 10.7% of sharks, skates, and rays, and 62.5% of all lobe-finned fish species are displayed in public aquariums (da Silva et al. 2019).

Conservation cannot be done in a vacuum. For example, the Tennessee Aquarium was part of a team that discovered the few remaining populations of the Barrens Topminnow (Fundulus julisia), an endangered fish that occurs only in isolated springs of Tennessee (George et al. 2013). The Barrens Topminnow is endangered because many spring ponds and runs were converted to livestock pastures or plant nurseries, and the introduced Western Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) eat their young. These findings naturally led to proposing actions in concert with other conservation partners. Aquariums are ideally placed to influence public opinion and policy makers so that more species threatened by international trade are included on the list in the multilateral treaty, Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES 1973).

| Fish species on IUCN Red List | |

|---|---|

| Potosi Pupfish | Cyprinodon alvarezi |

| La Palma Pupfish | Cyprinodon longidorsalis |

| Butterfly Splitfin | Ameca splendens |

| Golden Skiffia | Skiffia francesae |

Table 6.1: Four fish species on IUCN Red List "Extinct in the Wild" held in public aquariums.

Public aquariums, because of their in-house expertise, can act quickly to collect and breed rare fish. Actions to prevent the extinction of the Barrens Topminnow include monitoring populations and propagating and stocking juveniles into existing or newly created spring habitats. The Tennessee Aquarium assisted with propagations and developed a program called “Keeper Kids,” where students on spring break help feed the Barrens Topminnows in a behind-the-scenes experience.

The breeding colonies of the Butterfly Splitfin (Figure 6.3) at the London Zoo and elsewhere serve as ark populations essential to the survival of this species. Butterfly Splitfins are endemic to the Río Ameca in western Mexico and almost extinct in the wild. Actions such as nonnative fish removal, stream restoration, and sanctuary designation may take decades before eventual introduction and survival in the wild. The Tennessee Aquarium is part of a large partnership to guide hatchery augmentation and recovery of the rarest darter in North America (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2019). The Conasauga Logperch (Percina jenkinsi), a federally endangered darter (Percidae), is found only in a 30-mile (48 km) stretch of the Conasauga River in Georgia and Tennessee (Moyer et al. 2015).

The Banggai Cardinalfish (Pterapogon kauderni), a small, endangered tropical cardinalfish in the family Apogonidae, is now bred and displayed in numerous public aquariums after overharvest in the wild drove wild populations to near extinction. Consequently, most Banggai Cardinalfish sold to hobbyists in the United States and European Union today are captive bred. Finally, the expertise in husbandry has led to high standards for care of fish in captivity and numerous published husbandry manuals (Grassman et al. 2017).

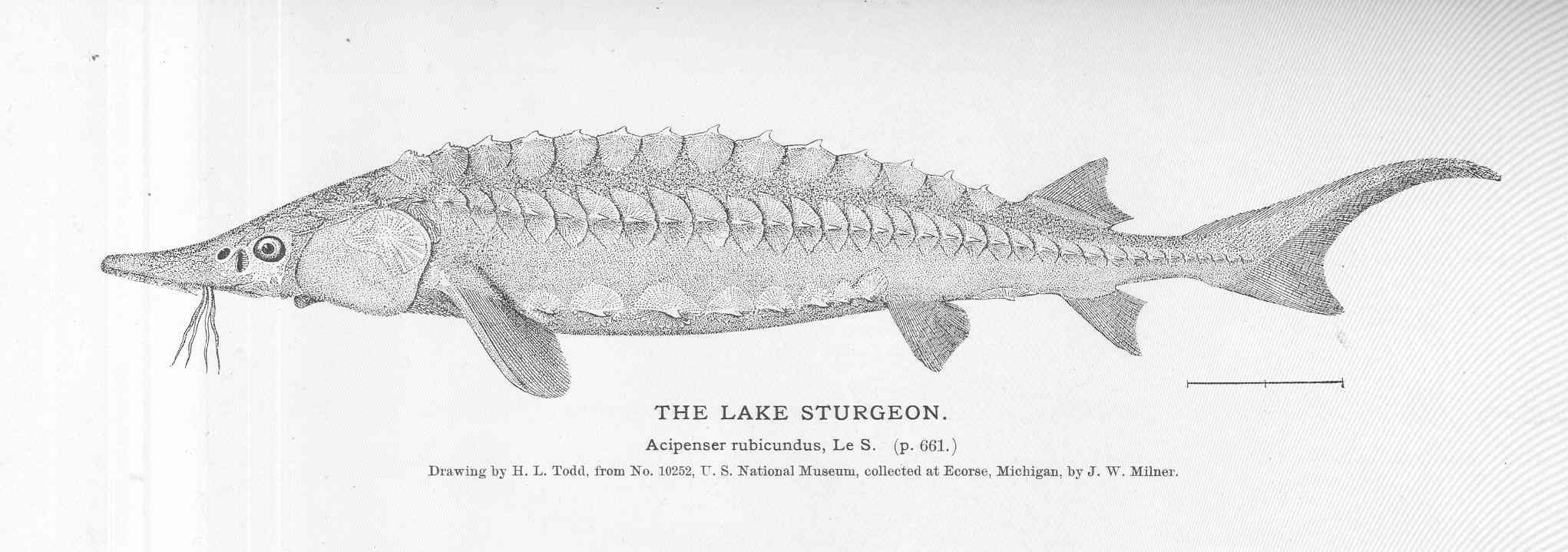

The Saving the Sturgeon program is a collaborative effort to reintroduce Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens, Figure 6.4) into the Tennessee River and surrounding waters (George et al. 2013). Lake Sturgeon, an important commercial species, was once abundant throughout the Great Lakes and Mississippi River drainages. It was overfished, and spawning migrations were blocked by construction of dams. By the 1970s it was extirpated from the Tennessee River. This collaborative program is a formal partnership of the Tennessee Aquarium, Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute, Tennessee Tech University, University of Tennessee, Tennessee Valley Authority, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, World Wildlife Fund, Conservation Fisheries Inc., Tennessee Clean Water Network, and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. The working group raises Lake Sturgeon for release as juveniles and collaborates with commercial and recreational anglers to monitor their health. The Tennessee Aquarium raises awareness and money for the conservation initiative. It also maintains a sturgeon touch-tank display and teaches elementary schoolchildren about sturgeon rearing, life history, and conservation. Touch displays for sturgeon are popular, as visitors can feel the unique leathery texture of the sturgeon’s skin and the hard bony plates.

6.7 Seahorse Conservation

Public aquariums are places where people first encounter the fascinating seahorses. The family Syngnathidae includes seahorses, sea dragons, sea moths, and pipefish. Because these are not targets of commercial or recreational fisheries, public aquariums first introduced them to the public. The World Aquariums and Zoo Association and Project Seahorse have worked collaboratively to improve husbandry of seahorses in order to decrease pressure on wild populations (Lunn et al. 1999; Koldeway et al. 2015; Muka 2018). Currently, rearing techniques are available for a dozen seahorse species. Aquariums were integral to studying biology and behavior (discover), distributing captive-bred specimens (act), and educating about their conservation status (share; Figure 6.3). The Association of Zoos and Aquariums organizes experts regarding the husbandry, veterinary care, conservation needs/challenges, research priorities, ethical considerations, and other issues of seahorse conservation (AZA 2014). The attention we give to seahorses in captivity is a necessary condition for conservation since many seahorse species are classified as vulnerable or worse (IUCN 2020). Trade in seahorses is highly regulated, and seahorses in public aquariums must be legally sourced.

The ethics of caring is illustrated by many stories about the fish in captivity, and in particular stories about the seahorses. Part of caring about a being is to be (1) curious about it, (2) willing to learn about it, and (3) responsible for its well-being (Schmitt 2017). A thoughtful person, in learning about the breeding and care for seahorses, is impressed and fascinated by the story of the male seahorse providing parental care in a protective pouch and nutrients and ionic balance to ensure normal embryonic development (Figure 6.5). The normal function of a female’s uterus is provided by the male seahorse. In addition, the appearance of seahorses swimming upright with curved neck, long snout, and tail that curls around a blade of seagrass or coral makes them unique in the world of fish.

Seahorses may be one of the very few fish to possess nonhuman charisma and operate as flagship species for conservation (Lorimer 2007). Flagship species are popular, charismatic symbols, and they serve as rallying points to stimulate conservation awareness and action (Leader-Williams and Dublin 2000). Seahorses live in some of the world’s most threatened habitats, and their plight has led to creation of marine protected areas and restoration projects. Recently, the rare Weedy Seadragon (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus) was raised at the Birch Aquarium, California. Saving seahorses means saving our seas.

Question to ponder:

In what ways do public aquariums educate the public? View this one-minute video developed by the Birch Aquarium to see how effective a short video can be for public education.

6.8 Efforts to Influence Seafood Choices

Marine environments are inaccessible to many due to simple facts of inland geographic locations or the lack of boats or equipment. Consequently, viewing displays at public aquariums is as close as most people come to experiencing marine life. One personal connection that even the inland residents have is our consumption of seafood. Consequently, public aquariums may educate visitors about challenges of providing sustainable seafood to consumers. In making personal choices about our seafood, we should ask: (1) Where did it come from? (2) Is it farmed or wild caught? And (3) If it’s wild, how was it caught? In 1999, in response to global overfishing, the Monterey Bay Aquarium began working to solve the most critical barriers to transitioning to sustainable seafood. Today, the aquarium staff reaches an online audience of over 3 million followers who regularly seek reliable, up-to-date information on sustainable seafood at the Seafood Watch® website, https://www.seafoodwatch.org/.

Seafood Watch summarizes information for seafood businesses, restaurants, and consumers by categorizing seafood choices as best choice, certified, good alternative, or avoid. Most fish on restaurant menus or in grocery stores do not mention source, so consumers are not able to make wise choices. Seafood Watch develops recommendations based on environmental protection, social responsibility, and economic viability. Best choice seafood would be grown or harvested in ways that protect the environment and maintain fish for the future. Three aquariums in France, Italy, and Spain launched a similar campaign, called Mr. Goodfish, www.mrgoodfish.com, to promote consumer awareness of sustainable seafood purchases.

Consumers in the United States import 90% of the seafood consumed, and a willingness to pay a premium to buy sustainable seafood has a global impact.

6.9 Ethical Considerations for Public Aquariums

Zoos and aquariums grapple with many conservation and welfare questions, such as, “What constitutes our conservation obligations? What is the moral and scientific basis of aquariums? And, Should aquariums exist at all?” (Mazur and Clark, 2001, 185). Where can we obtain live fish for displays? In captivity animals may be deprived of needed interaction. Some people may believe that deriving entertainment from sentient animals is wrong. Increasingly, aquariums are dealing with such questions about their ethical obligations to aquatic animals through AZA standards (Bekoff 2014).

Most public aquariums are not-for-profit organizations and seek grants and donations to maintain conservation and science programs and exhibits. Monterey Bay Aquarium was built and fully funded with a gift from David and Lucile Packard. Georgia Aquarium, the largest aquarium in the United States, was built in 2000 at a cost of $290 million, most from donations. Promoters for new aquarium construction sell them as both conservation initiatives and as enterprises that bring jobs and revenues to revitalize distressed downtowns. Tax breaks and bonds often subside public aquarium construction. Most also charge a daily entrance fee and annual memberships. Aquarium professionals have seen great variation in attendance, with high attendance numbers in the first years followed by dramatic declines if new exhibits are not developed and promoted (Lindquist 2018). Funding to support research and conservation efforts must compete with funds for maintenance and operations. Georgia Aquarium’s international Whale Shark research and conservation program is funded in part by proceeds from sales of a Whale Shark IPA launched by the Atlanta Brewing Company. Other innovative funding solutions exist in many public aquariums.

Many have begun to question moral acceptability of keeping animals in captivity. Do the benefits of keeping fish in captivity accrue to the institutions more than to conservation in the wild? How can we justify our captive animal programs based on attention and protection of species in the wild? Animal rights advocates stress that fish are valuable in and of themselves (they have inherent value) and that their lives are not just valuable because of what they can do for humans (their utility). In their view, the right actions are not found by invoking utilitarianism, in which the general rule of thumb is that the right actions are those that maximize utility summed over all those who are affected by the actions. No matter what you believe, animal welfare concerns must be a priority for public aquariums that exhibit fish.

Principles of ethics, compassion, humility, respect, coexistence, and sustainability should guide us in our interactions with aquarium animals. As we learn more about inner workings of the mind of fish, societal forces will increasingly ask about the level of respect and moral consideration given to fish (Bekoff 2014). These are not new questions, and we don’t yet have satisfactory answers, but we should expect to engage in dialogue.

Public aquariums believe there should be no boundaries to visitation. Therefore, exhibits, restrooms, and parking are fully accessible, and public transportation is available. In addition, some visitors with sensory processing disorders or photosensitive considerations are accommodated by scheduling low-sensory presentations with reduced volume and dimmed lighting. Assisted-listening devices and American Sign Language interpreters are often available for the hearing-impaired visitors. Audio-described presentations and tactile models are provided for the vision-impaired visitors.

Public aquariums maintain large and diverse collections of live animals for display and are committed to sustainability of aquatic animal trade (Tlusty et al. 2013, 2017). Some collect their own specimens but also share and engage in ornamental trade. The accreditation of Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) requires that suppliers do not cause environmental damage when collecting specimens and that they have all required legal permits. Consequently, they are interested in supporting sustainable trade by educating consumers and retail chains about best options for purchasing ornamental fish.

In addition, public aquariums encourage and communicate the examples of sustainable ornamental fish trade, such as the Rio Negro cardinal tetra fishery (Chao and Prang 1997). Nearly 20 million live fish are exported from the region annually, generating more than U.S. $2 million annually for the local economy. In some cases, such as sharks and rays, captive populations are challenging to sustain. Therefore, public aquariums engage in comprehensive assessments of the sustainability of future harvests so they can protect wild populations and permit some harvest for live displays (Buckley et al. 2018). In other cases, aquariums may have enough captive-bred fish to permit sharing among other aquariums. Zebra Sharks (Stegostoma tigrinum)—commonly known as Leopard Sharks throughout the Indo-Pacific—have declined in the wild. Public aquariums are assisting in recovery via introduction of juveniles bred in managed care and hatched from eggs supplied by participating AZA–accredited facilities.

Displays are increasingly designed for immersive experience for public education. Not all species are suited or captivity and display. If an animal suffers from being on display, it will never be a good specimen (Leddy 2012; Semczyszyn 2013). If the visitor finds the display is undignified, then it will not be a good display for aesthetic, education, or scientific purposes. Public aquariums are getting larger; the Atlanta Aquarium’s largest tank is 23,850,000 liters (that’s 6.3 million gallons) (Lindquist 2018). Keeping some fish, such as Whale Sharks and Great White Sharks in captivity, is controversial due to their feeding and extensive movements (Bruce et al. 2019; Roy 2019).

While public aquariums are places where visitors go to appreciate aquatic environments, for many of us, they remain the only glimpse of the underwater world. Yet, aquarium displays are human-created artifacts and not natural. The rapidly changing ethical and social perspective means that issues of animal welfare, animal rights, climate change, captive breeding, and commercialization may create tensions. Built displays will always be different from appreciation of nature and the natural environment (Semczyszyn 2013). Therefore, in addition to meeting the life requirements of live specimens, the aquarium displays must pay attention to the aesthetic experience. One alternative display option is to create smaller, more interactive models (Lindquist 2018, 343), such as touch displays for stingrays and sturgeon. In other aquarium displays, the display tanks are designed as invisible to focus attention on the living specimens. Choices made about displays recognize that not all species are equally suited to life on display.

Energy demands of large aquariums are substantial, with vast quantities of water and air that must be heated or cooled and treated. Electricity production generates waste as carbon dioxide (CO2). Shedd Aquarium’s CO2 emissions were once compared with “an endless 2,200 car traffic jam” (Wernau 2013), before a major initiative to reduce energy consumption, reduce and reuse water, and reduce waste (Shedd Aquarium 2020). The Aquarium Conservation Partnership is a new initiative that shares best practices in conservation actions designed to make conservation a core business strategy of public aquariums.

Profile in Fish Conservation: Karen J. Murchie, PhD

Karen J. Murchie is the Director of Freshwater Research at Shedd Aquarium, where she oversees a team of biologists focused on freshwater biodiversity conservation in the Great Lakes region. Her early experiences spending much time outside, from exploring a local conservation area near her home to a summer experience in a ranger program, led to an appreciation for nature. The first time she donned a mask and snorkel in Jamaica, a small purple and yellow Fairy Basslet entered her view and hooked her on a career in fisheries. Her experiences allowed her to learn about fish and explore aquatic habitats in the Caribbean, the Arctic, the Amazon, and many other places. Her first fisheries jobs included some environmental consulting gigs examining stream crossings and also working with American Eels on the St. Lawrence River, and then longer-term positions with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in the Great Lakes region, followed by an environmental consulting job in the Northwest Territories of Canada. After completing her PhD at Carleton University, she worked as an Assistant Professor at the College of The Bahamas (now University of The Bahamas), where she taught biology courses and did research on bonefish through engagement with local guides and fishing lodge owners.

In 2016, she joined Shedd Aquarium as research biologist and instructor, which exposed her to the important roles that public aquariums play in education and conservation. In addition to maintaining a rigorous research program focused on migratory fish in collaboration with other researchers and fisheries practitioners, she also instructed a yearly fall semester course in Freshwater Ecology to college students at Shedd, through the Associated Colleges of the Chicago Area. In this course, students are connected with many hands-on opportunities related to local conservation work in the greater Chicago area.

In 2019, Karen became the Director of Freshwater Research at Shedd and began to oversee a team of freshwater biologists, in addition to running the migratory fish conservation research program. Education and outreach, whether through collaborative programs with the Learning and Community Department at Shedd, engagement of the public in community science, or sharing knowledge through seminars, activities in the aquarium and via social media are all aspects of the position. Dr. Murchie enjoys highlighting the value of the often-overlooked freshwater fish through her fieldwork and various public engagement activities.

Key Takeaways

- Public aquariums have an important role in communicating the issues, raising awareness, changing behaviors, and gaining widespread public and political support for conservation actions.

- Conservation education and inspiration for their visitors are common missions of public aquariums.

- As people learn more about the things they care about, then they may act to protect and conserve the species and ecosystems that they are aware of and value.

- The restorative nature of visiting public aquariums is difficult to study, but an interest in therapeutic intervention with aquatic animals continues.

- Public aquariums are expanding conservation efforts via the SAFE program, for Saving Animals from Extinction and other outreach programs.

- Despite the broad base of support and interests, public aquariums continue to face challenges by welfare advocates, climate activists, and conservationists.

- Public perceptions of aquariums range widely, and some people are concerned about the benefits and morality of keeping animals in captivity.

- Aquariums engage with the ornamental fish trade by promoting market-based initiatives that link retailers to captive-bred rather than wild-caught fish.

- Immersive exhibits provide more opportunities for aquarium visitors to interact with displayed animals.

This chapter was reviewed by Anna L. George and Karen J. Murchie.

URLs

Accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums: https://www.aza.org/inst-status

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pCDSzAsG3DY

Figure References

Figure 6.1: Smalltooth Sawfish from public aquarium display. Simon Fraser University, Communications & Marketing. 2007. CC BY 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/nRQ4G5.

Figure 6.2: Floating wetland at Inner Harbor, Baltimore. Ron Cogswell. 2015. CC BY 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/vRqNqx.

Figure 6.3: Photo of the critically endangered Butterfly Splitfin (Ameca spendens). Przemysław Malkowski. 2008. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ameca_splendens.jpg.

Figure 6.4: Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens). George Brown Goode. 1884. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FMIB_51148_Lake_Sturgeon.jpeg.

Figure 6.5: Two pregnant Potbelly Seahorses at the Tennessee Aquarium, USA. Joanne Merriam. Unknown date. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://www.academia.edu/31808923/Interspecies_Care_in_a_Hybrid_Institution.

Figure 6.6: Karen J. Murchie, PhD. Used with permission from Karen J. Murchie. Photo by Shedd Aquarium/Brenna Hernandez. Use of the contribution is permitted at no cost in perpetuity in this and all future versions of this work.

Text References

AZA. 2011. The accreditation standards and related policies. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD.

AZA. 2014. Taxon advisory group (TAG) handbook. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD.

Ballantyne, R., and J. Packer. 2016. Visitors’ perceptions of the conservation education role of zoos and aquariums: Implication for the provision of learning experiences. Visitor Studies 19:193–21. doi:10.1080/10645578.2016.1220185.

Barongi, R., F. A. Fisken, M. Parker, and M. Gusset. 2015. Committing to conservation: the World Zoo and Aquarium conservation strategy. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums Executive Office, Gland, Switzerland.

Bekoff, M. 2014. Aquatic animals, cognitive ethology, and ethics: questions about sentience and other troubling issues that lurk in turbid water. Antennae: Journal of Nature in Visual Culture 28:5–22.

Bergl, R. 2017. Patterns and drivers of public favorability towards zoos and aquariums. Directors’ Policy Conference, Association of Zoos and Aquariums, 25 January, Corpus Christi, TX.

Brooks, H. L., K. Rushton, K. Lovell, P. Bee, L. Walker, and L. Grant, and A. Rogers. 2018. The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 18(1):31.

Brown, C. 2015. Fish intelligence, sentience and ethics. Animal Cognition 18:1–17.

Bruce, B. D., D. Harasti, K. Lee, C. Gallen, and R. Bradford. 2019. Broad-scale movements of juvenile white sharks Carcharodon carcharias in eastern Australia from acoustic and satellite telemetry. Marine Ecology Progress Series 619:1–15.

Buckley, K. A., D. A. Crook, R. D. Pillans, L. Smith, and P. M. Kyne. 2018. Sustainability of threatened species displayed in public aquaria, with a case study of Australian sharks and rays. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 28:137–151.

Chao, N. L., and G. Prang. 1997. Project Piaba: towards a sustainable ornamental fishery in the Amazon. Aquarium Science and Conservation 1:105–111.

CITES. 1973. Convention on international trade in endangered species of wild fauna and flora. https://cites.org/eng/disc/text.php.

Clark, E. 1951. Lady with a spear. Harper and Brothers, New York.

Clements, H., S. Valentin, N. Jenkins, J. Rankin, J. S. Baker, and N. Gee, D. Snellgrove, and K. Sloman. 2019. The effects of interacting with fish in aquariums on human health and well-being: s systematic review. PLoS ONE 14 (7):e0220524. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220524.

Cracknell, D. L., S. Pahl, M. P. White, and M. H. Depledge. 2018. Reviewing the role of aquaria as restorative settings: how subaquatic diversity in public aquaria can influence preferences, and human health and well-being. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 23:446–460.

da Silva, R., P. Pearce-Kelly, B. Zimmerman, M. Knott, W. Foden, and D. A. Conde. 2019. Assessing the conservation potential of fish and corals in aquariums globally. Journal of Nature Conservation 48:1–11.

Dropkin, L., S. Tipton, and L. Gutekunst. 2015. American millennials: cultivating the next generation of ocean conservationists. Edge Research and David and Lucille Packard Foundation, Arlington, VA. Available at: https://www.packard.org/insights/resource/american-millennials-cultivating-the-next-generation-of-ocean-conservationists/. Assessed September 11, 2019.

Dulvy, N. K., S. L. Fowler, J. A. Musick, R. D. Cavanagh, P. M. Kyne, L. R. Harrison, J .K. Carlson, L. N. K. Davidson, S. V. Fordham, M. P. Francis, C. M. Pollock, C. A. Simpfendorfer, G. H. Burgess, K. E. Carpenter, L. J. V. Compagno, D. A. Ebert, C. Gibson, M. R. Heupel, S. R. Livingstone, J. C. Sanciangco, J. D. Stevens, S. Valenti, and W. T. White. 2014. Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. eLife 3:e00590 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.00590.

Dwyer, J. T., J. Fraser, J. Voiklis, U.G. Thomas. 2020. Individual-level variability among trust criteria relevant to zoos and aquariums. Zoo Biology 39:297–303.

Falk, J. H., E. M. Reinhard, C. L. Vernon, K. Bronnenkant, N. L. Deans, and J. E. Heimlich. 2007. Why zoos & aquariums matter: assessing the impact of a visit to a zoo or aquarium. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD.

Fennel, D. A. 2012. Tourism and animal ethics. Routledge, New York.

Fulmer, A. C., and M. J. Gelfand. 2012. At what level (and in whom) we trust: trust across multiple organizational levels. Journal of Management 38(4):1167–1230.

Gee, N. R., T. Reed, A. Whiting, E. Friedman, D. Snellgrove, and K. A. Sloman. 2019. Observing live fish improves perceptions of mood, relaxation and anxiety, but does not consistently alter heart rate or heart rate variability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16(17):3113 https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/17/3113.

George, A. L., J. R. Ennen, and B. R. Kuhajda. 2019. Protecting an underwater rainforest: freshwater science in the southeastern United States. Pages 64–90 in A. B. Kaufman, M. J. Bashaw, and T. L. Maple, editors, Scientific foundations of zoos and aquariums: Their role in conservation and research, Cambridge University Press.

George, A. L., M. T. Hamilton, and K. F. Alford. 2013. We all live downstream: engaging partners and visitors in freshwater fish reintroduction programmes. International Zoo Yearbook 47:140–150.

Goode, G. B. 1884. Fisheries and fishery industries of the United States. Section I: Natural history of useful aquatic animals, plates. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Grassmann, M., B. McNeil, and J. Wharton. 2017. Sharks in captivity: the role of husbandry, breeding, education, and citizen science in shark conservation. Advances in Marine Biology 78:89–119. doi: 10.1016/bs.amb.2017.08.002. Epub 2017 Sep 15. PMID: 29056144.

Grow, S., D. Luke, and J. Ogden. 2018. Saving animals from extinction (SAFE): unifying the conservation approach of AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums. Pages 122–128 in B. Minteer, J. Maienschein, and J. P. Collins, editors, The ark and beyond: the evolution of zoo and aquarium conservation. University of Chicago Press.

Gusset, M., and G. Dick. 2011. The global reach of zoos and aquariums in visitor numbers and conservation expenditures. Zoo Biology 30:566–569.

Happel, A., K. J. Murchie, P. W. Willink, and C. R. Knapp. 2020. Great Lakes fish finder app; a tool for biologists, managers and educational practitioners. Journal of Great Lakes Research 46:230–236.

Hillard, J. M. 1995. Aquariums of North America: a guidebook to appreciating North America’s aquatic treasures. Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD, and London.

Huber, B., M. Barnidge, and H. G. de Zúñiga. 2019. Fostering public trust in science: the role of social media. Public Understanding of Science 28:759–777.

IUCN. 2020. The IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2020-2. International Union for Conservation of Nature, Gland, Switzerland. https://www.iucnredlist.org.

Jacobson, S. K., N. A. Morales, B. Chen, R. Soodeen, M. P. Moulton, and E. Jain. 2019. Love or loss: effective message framing to promote environmental conservation. Applied Environmental Education & Communication 18(3):252–265.

Knapp, C. R. 2018. Beyond the walls: applied field research for the 21st century public aquarium and zoo. Pages 286–297 in B. Minteer, J. Maienschein, and J. P. Collins, editors, The ark and beyond: the evolution of zoo and aquarium conservation. University of Chicago Press.

Koldeway, H. 2005. Syngnathid husbandry in public aquariums. 2005 manual. Project Seahorse and Zoological Society of London. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55930a68e4b08369d02136a7/t/5602efcbe4b033fa74554e82/1443033035533/Syngnathid_Husbandry_Manual2005.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2021.

Langfield, J., and C. James. 2009. Fishy tales: experiences of the occupation of keeping fish as pets. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 72:349–356.

Leader-Williams, N., and H. Dublin. 2000. Charismatic megafauna as “flagship species.” Pages 53–81 in A. Entwistle and N. Dunstone, editors, Priorities for the conservation of mammalian diversity. Cambridge University Press.

Leddy, T. 2012. Aestheticisation, artification, and aquariums. Contemporary Aesthetics 4. Special vol. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7523862.spec.406.

Levine, G. N., K. Allen, L. T. Braun, H. E. Christian, E. Friedmann, K .A. Taubert, S. A. Thomas, D. L. Wells, and R. A. Lange. 2013. Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 127(23):2353–2363.

Lindquist, S. 2018. Today’s awe-inspiring design, tomorrow’s Plexiglas dinosaur: how public aquariums contradict their conservation mandate in pursuit of immersive underwater displays. Pages 329–343 in B. Minteer, J. Maienschein, and J. P. Collins, editors, The ark and beyond: the evolution of zoo and aquarium conservation. University of Chicago Press.

Loh, T-L., E. R. Larson, S. R. David, L. S. de Souza, R. Gericke, M. Gryzbek, A. S. Kough, P. W. Willink, and C. R. Knapp. 2018. Quantifying the contributions of zoos and aquariums to peer-reviewed scientific research. FACETS 3:287–299. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2017-0083.

Lorimer, J. 2007. Nonhuman charisma. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 25:911–932.

Louv, R. 2008. Last child in the woods. Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC.

Lunn, K. E., J. R. Boehm, H. J. Hall, and A. C. J. Vincent, editors. 1999. Proceedings of the First International Aquarium Workshop on Seahorse Husbandry, Management, and Conservation. John G. Shedd Aquarium, Chicago.

Marino, L. S., O. Lilienfeld, R. Malamud, H. Nobis, and R. Broglio. 2010. Zoos and aquariums promote attitude change in visitors? A critical evaluation of the American Zoo and Aquarium study. Society and Animals 18:126–138.

Maynard, L. 2018. Media framing of zoos and aquaria: from conservation to animal rights. Environmental Communication 12:177–190.

Mazur, N. A., and T. W. 2001. Zoos and conservation: policy making and organizational challenges. Yale Forestry and Environmental Science Bulletin 105:185–201.

Mellish, S., J. C. Ryan, E. L. Pearson, and M. R. Tuckey. 2019. Research methods and reporting practices in zoo and aquarium conservation-education evaluation. Conservation Biology 33:40–52.

Miller, B., W. Conway, R. P. Reading, C. Wemmer, D. Wildt, D. Kleiman, S. Monfort, A. Rabinowitz, B. Armstrong, and M. Hutchins. 2004. Evaluating the conservation mission of zoos, aquariums, botanical gardens, and natural history museums. Conservation Biology 18:86–93.

Moss, A., E. Jensen, and M. Gusset. 2015. Evaluating the contribution of zoos and aquariums to Aichi Biodiversity Target 1. Conservation Biology 29:537–544.

Moyer, G. R., A. L. George, P. L. Rakes, J. R. Shute, and A. S. Williams. 2015. Assessment of genetic diversity and hybridization for the endangered Conasauga Logperch (Percina jenkinsi). Southeastern Fishes Council Proceedings 55. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings/vol1/iss55/6.

Mubanga, M., L. Byberg, C. Nowak, A. Egenvall, P. K. Magnusson, E. Ingelsson, and T. Fall. 2017. Dog ownership and the risk of cardiovascular disease and death—a nationwide cohort study. Scientific Reports 7(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-016-0028-x.

Muka, S. 2018. Conservation constellations: aquariums in aquatic conservation networks. Pages 90–103 in B. Minteer, J. Maienschein, and J. P. Collins, editors, The ark and beyond: the evolution of zoo and aquarium conservation, University of Chicago Press.

Murchie, K. J., C. R. Knapp, and P. B. McIntyre. 2018. Advancing freshwater biodiversity conservation by collaborating with public aquaria: making the most of an engaged audience and trusted arena. Fisheries 43(4):172–178.

Murr, A. 1988. The age of aquariums. Newsweek 112(20):26.

Myers, G. 2007. The significance of children and animals: social development and our connections to other species. 2nd ed. Purdue University Press, West Lafayette, IN.

Ostrom, E. 2003. Toward a behavioral theory linking trust, reciprocity, and reputation. Pages 19–79 in E. Ostrom and J. Walker, editors, Trust and reciprocity. Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

Palmer, C., T. J. Kasperbauer, and P. Sandøe. 2018. Bears or butterflies? How should zoos make value-driven decisions about their collections? Pages 179–191 in B. Minteer, J. Maienschein, and J. P. Collins, editors, The ark and beyond: the evolution of zoo and aquarium conservation, University of Chicago Press.

Rank, S. J., J. Volkis, R. Gupta, J. R. Fraser, and K. Flinner. 2018. Understanding organizational trust of zoos and aquariums. K. P. Hunt, editor. Understanding the role of trust and credibility in science communication. https://doi.org/10.31274/sciencecommunication-181114-16.

Reid, G. McG., T. C. MacBeath, and C. K. Csatádi. 2013. Global challenges in freshwater-fish conservation related to public aquariums and the aquarium industry. International Zoo Yearbook 47:6–45. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/izy.12020.

Riddick, C. C. 1985. Health, aquariums and the institutionalized elderly. Marriage and Family Review 8(3–4):163–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v08n03_12.

Roy, I. 2019. The real reason aquariums never have Great White Sharks. Reader’s Digest, June 21, 2019. https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/real-reason-aquariums-never-great-172748770.html.

Rutger, H. 2015. Remembering Mote’s “Shark Lady”: the life and legacy of Dr. Eugenie Clark. Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium website. Available at: https://mote.org/news/article/remembering-the-shark-lady-the-life-and-legacy-of-dr.-eugenie-clark. Accessed February 2, 2021.

Schmitt, S. 2017. Care, gender, and survival: the curious case of the seahorse. In Troubling species: care and belonging in a relational world. RCC Perspectives: Transformations in Environment and Society 2(1)83–89. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7778.

Semczyszyn, N. 2013. Public aquariums and marine aesthetics. Contemporary Aesthetics 11. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7523862.0011.020.

Shedd Aquarium. 2020. Sustainability at Shedd 2020: waste not. Available at: https://www.sheddaquarium.org/stories/sustainability-at-shedd-2020-waste-not. Accessed March 20, 2023.

Spooner, S. L., M. J. Farnworth, S. J. Ward, and K. M. Whitehouse-Tedd. 2021. Conservation education: Are zoo animals effective ambassadors and is there any cost to their welfare? Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 2:41–65. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg2010004.

Stanley, I. H., Y. Conwell, C. Bowen, and K. A. Van Orden. 2014. Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging and Mental Health 18(3):394–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.837147.

Stern, M. J., and K. J. Coleman. 2015. The multi-dimensionality of trust: applications in collaborative natural resources management. Society and Natural Resources 28:117–132.

Stern, P. C., T. Dietz, T. Abel, G. A. Guagnano, and L. Kalof. 1999. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: the case of environmentalism. Human Ecology Review 6:81–97.

Thaler, R. H., and C. R. Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Tlusty, M. F., A. L. Rhyne, L. Kaufman, M. Hutchins, G. M. Reid, C. Andrews, P. Boyle, J. Hemdal, F. McGilvray, and S. Dowd. 2013. Opportunities for public aquariums to increase the sustainability of the aquatic animal trade. Zoo Biology 32:1–12.

Tlusty, M. F., N. Baylina, A. L. Rhyne, C. Brown, and M. Smith. 2017. Public aquaria. Pages 611–622 in R. Calado, I. Olivotto, M. P. Oliver, and G. J. Holt, editors, Marine ornamental species aquaculture, John Wiley & Sons, Somerset, NJ.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2019. Revised recovery plan for the Conasauga Logperch (Percina jenkinsi). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior, South Atlantic-Gulf Region, Athens, Georgia. Available at: https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/Conasauga%20Logperch%20Recovery%20Plan%20Signed_FINAL_2.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2021.

Valenti, J. M., and G. Tavana. 2005. Report: continuing science education for environmental journalists and science writers (in situ with the experts). Science Communication 27 (2):300–310.

Wells, D. L. 2005. The effect of videotapes of animals on cardiovascular responses to stress. Stress and Health 21:209–213.

Wernau, J. 2013. Shedd Aquarium looks to slice energy bill. Chicago Tribune, January 26. https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-xpm-2013-01-26-ct-biz-0126-shedd-energy-20130126-story.html. Accessed February 2, 2021.

Young, A., K. A. Khalil, and J. Wharton. 2018. Empathy for animals: a review of the existing literature. Curator: The Museum Journal 61(2):327–343.

- I use the term public aquarium to include institutions, such as aquariums and marine parks, open to the public that may be supported by private or public funds. ↵

Constructed by humans

Keeping something in same position or moving in same direction

Addresses multiple species with one action plan

Situated in the original place

Process of growing plants in sand, gravel, or liquid

Naturally accompanying or associated

Person actively engaged in an art, discipline, or profession