7 Gender and Fishing

Learning Objectives

- Describe the roles that women play in fishing, fisheries, and aquaculture.

- Recognize the contributions of women to the science of managing fish and fishing.

- Explain the activities of governance where women’s issues are not recognized.

- Explore intersectionality as a starting point for discussions of human rights and social justice related to fish conservation.

7.1 Why Gender Is Relevant to Sustainable Fishing

The old axiom goes “Give a man a fish and he eats for a day. Teach a man to fish and he eats for a lifetime.” A feminist version of this would be, “Teach a woman to fish, and everyone eats for a lifetime” (Sharma 2014). Contributions of women in fishing and fisheries science have been historically invisible because someone else got credit for them. Furthermore, in scientific fields dominated by white males, harassment and other behaviors discourage participation by women. Women’s contributions to fishing communities may be direct or indirect, such as: (1) direct contribution of women’s labor in catching or processing operations; (2) creating the next generation by bearing and raising children; and (3) special responsibilities because of the absence of men away while fishing (Thompson 1985). In some fisheries, the catching of fish for sale is dominated by males, while the catching of fish for feeding the family is dominated by females (Bennett 2005; Santos et al. 2015; Ameyaw et al. 2020; Tilley et al. 2020).

Women hold knowledge, skills, and traditions relevant for fisheries management. However, despite the seemingly valuable contributions, women are often not paid for their work and, consequently, women’s fishing activities are not included in official statistics. Because of both diminished appreciation and differing roles, women in the fishing industry are likely to have a smaller role in governance and suffer disproportionately during difficult times. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic affected women fishers differently due to gender-based norms or restrictions (Lopez-Ercilla et al. 2021; Woskie and Wenham 2021). More inclusive consideration of gender in fishing should result in more sustainable fisheries, yet important obstacles remain.

Gender refers to a social construct based on how women and men relate. Thus, gender is expressed in behaviors, roles, social status, and rights of women and men as organized and justified by society on the basis of biological differences between the sexes. However, gender analysis in fisheries is impossible without observations and data by gender or sex. Categorization of gender and sex as binary (i.e., male or female) is not a full or accurate portrayal of the diversity of human behavior or biology. American adults identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersexual, or asexual (LGBTQIA) rose to 5.6 percent in a 2021 Gallup poll (Jones 2021). LGBTQIA adults are unlikely to see themselves represented in fishing and fish conservation arenas and other groups.

Increasingly, we are examining gender differences in participation in different types of fishing. Much of this work has focused on small-scale subsistence fishing, where fisheries support the economy of local communities (Campbell et al. 2021). Contributions of women in all types of fisheries, as well as in fisheries science and management, are overlooked by society, industry, and policy makers. However, the premise and promise of sustainability is rooted in the belief that no effort to restore ecological balance and integrity will succeed if it does not also address the social inequities and human suffering in our communities.

In this chapter, I examine implicit biases related to gender and fishing and encourage you to consciously and explicitly consider gender and diversity of those engaged in fishing. A modern view of fisheries should begin with the assumption that women do fish, rather the inverse. When we take a gender perspective, we identify where there are differences that generate inequalities, vulnerabilities, fears, and exclusion. Transforming harmful social ideas and practices requires everyone’s collaboration, regardless of their gender. This more inclusive view will bring women and historically underrepresented groups into the management process and will provide the base for better governance and policy reform.

Questions to ponder:

What is gender? What gender-related information would you want to have in order to manage a fishery or conserve a threatened fish population?

7.2 Harmful Fishing Stereotypes

A stereotype is any overgeneralized, widely accepted opinion, image, or idea about a person, place, or thing. We use stereotypes to simplify our world and reduce the amount of thinking we have to do. You may have heard someone remark that “women are bad luck on boats,” “girls are bad drivers,” “women are too emotional,” “the humanities are useless,” or “males are better at math.” At a boat ramp or fishing pier, one might hear that “you did really well for a woman,” which leads to anger and hostility. Stereotypes are harmful because we don’t work to see or understand the person and their identity. Instead, we substitute the stereotype. Such stereotypes may serve as self-fulfilling prophecies and affected individuals are at risk of being marginalized. Stereotypes may also lead to hostility between groups. Imagine that you are being judged and labeled without sharing anything about your creativity and uniqueness.

Our language continues to support the stereotype that those who catch fish are males. The term “fishermen” dominated the scientific literature in fisheries during most of the 20th century. Attempts to use gender-neutral terms, such as fisher or fisherfolk, have been increasing to the point that fishers and fishermen occurred equally in the most recent literature (Branch and Kleiber 2015). According to Welch (2019), women do not consistently take offense from the term “fishermen.” Two quotes from females are instructive:

I enjoy the term fishermen. I’d much rather be called a fisherman than a fisher woman. I feel like it would separate me as crew. I don’t want to be treated like a woman on the boat. I want to be treated like a crew member.

As a woman I have always considered myself a fisherman. My dad taught me how to fish, and I feel like it is something that is important to many families. Especially father daughter relationships and I think it should stay the way that it is.

The way we govern fisheries is influenced by gender stereotypes. Holding a stereotypic view that only males do the fishing means that access to fishing grounds, ownership of fishing boats, and the rights to fish are considered the domain of males (Figure 7.1). Therefore, males often have greater support from governing bodies in controlling harvest and influencing decisions than do females. Unfortunately, this leads to poor management decisions and marginalizing the role of women in fishing communities.

Questions to ponder:

What familiar stereotypes have you encountered? Are they positive or negative? What gender-neutral term do you typically use to describe one who harvests fish? Why would you prefer to use a gender-neutral term?

7.3 Gender Issues That Prevent Gender Equality

Women are a minority in many male-dominated sectors of fishing value chains, fisheries management, and fisheries science. Gender equality is not only a basic human right, but its achievement has enormous socioeconomic ramifications. Creating a world without gender-based discrimination is a global priority. Therefore, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and others have encouraged the use of a gender lens to examine and promote fisheries sustainability (FAO 2015, 2017; Kleiber et al. 2017). Only by applying a gender lens can we identify and eliminate barriers that exclude women from equal access to fisheries jobs, markets, and fishing resources. Avoidance of gender discrimination requires each of us to speak up and oppose inappropriate sexist behaviors and policies.

Sexism refers to any prejudicial attitudes or discrimination against women on the basis of their sex alone. Sexism is evident in our (a) beliefs, (b) behaviors, (c) use of language, and (d) policies reflecting and conveying a pervasive view that women are inferior (Herbst 2001). Nine issues are so engrained in society that most people experience one of these at some point but may fail to identify or call it out:

- Gender stereotypes

- Unrealistic body standards

- Unequal pay

- Negative female portrayals

- Sexist jokes

- Shaming language

- Gender roles

- Sexual harassment

- Toxic masculinity

Gender stereotypes. Many cultures around the world adopt a patriarchy—that is, a hierarchical system of social organization in which cultural, political, and economic structures are controlled by men. Male hegemony refers to the political and ideological domination of women in society.

Among those who fish for sport, only 27% of U.S. anglers are female, and females appear on 10% of covers, in 9% of fishing images, and in 6% of hero images in sportfishing magazines. Only 1% of feature articles are authored by females (Carini and Weber 2017; Burkett and Carter 2020).

Unrealistic body standards. These unrealistic standards of beauty have psychological effects that lead to women fixating negatively on their weight and appearance. From an early age, girls are subjected to unrealistic body images. Fishing is an activity that should emphasize safety as a priority, not body image. Another unrealistic assumption is that females prefer pink and will buy pink-colored fishing attire (Merwin 2010).

Unequal pay. Globally, women represent about 50% of all seafood workers. Yet, female workers are consistently overrepresented in low-skilled, low-paid, low-valued positions, remaining mostly absent at the other end of the value chain (Briceño-Lagos and Monfort 2018). Women’s labor is likely to be viewed as being part of the household duties assisting their husbands, while the high-paid positions in fisheries are mostly occupied by men.

Negative female portrayals. While many women are experts in fishing, ecology, and conservation, this expertise is not reflected in media portrayals. Rather, media portrayals too often focus on the rarity of “females who fish,” rather than on the expertise these individuals possess. Males who fish are not judged by their appearance and neither should females.

Objectification. There are many examples of fishing cultures that sexually objectify women and seek and to share photos of scantily clad women showing off the fish they catch. Among the detrimental effects of sexual objectification (Miles-McLean et al. 2019; Sáez et al. 2019), we can expect that objectification is a barrier to participation.

Sexist comments and jokes. The purpose of sexist jokes or comments is to disparage women. For example, the sexist joke — “What do you call a woman with half a brain? Gifted”—conveys the notion that women as a group are not very smart. The use of humor decreases the perception that the speaker is sexist and ultimately decreases the probability that the listener will confront the perpetrator (Mallett et al. 2016). In male-dominated fields, such as fishing or fisheries science, the frequency of sexist jokes is likely higher. Sexist jokes result in stress and anxiety over how or whether to respond or confront. Furthermore, sexual jokes may increase tolerance of sexual harassment. Clearly, men view sexist humor as more humorous and less offensive than do women. In the workplace, women who experience sexual humor are less likely to be satisfied with their jobs and more likely to withdraw from the workplace. This inappropriate behavior continues until men are confronted about the unwelcome jokes. People often hesitate to confront sexism for fear of social repercussions. Women, in particular, may be accused of being overly sensitive when they confront the perpetrator.

Failing to call out the sexist joke teller is a tacit endorsement of inappropriate behavior and damages group culture. Confronting sexism means quickly expressing disapproval when a sexist comment or situation arises (Monteith et al. 2019; Woodzicka et al. 2020; Woodzicka and Good 2021). Direct responses to sexist jokes and comments using the following statements are most effective.

- That made me uncomfortable.

- That’s against our code of conduct.

- That wasn’t funny at all.

- I don’t get it, can you explain.

- Disrespectful words are not tolerated here.

Shaming language. Shaming or patronizing language toward women—for example, explaining unnecessary things (e.g., mansplaining)—can make it more difficult to build productive working relationships in a male-dominated field. “Mansplaining” refers to the tendency of men to explain things to women, whether they need them explained or not. In many cases, a man may assume that a female is unaware of tips for winterizing a boat motor, finer points of baitcasting, or when to drift a nymph versus a dry fly. Adding further insult, the man may interrupt or speak over women, a behavior sometimes referred to as “manterrupting.” Often, men may compliment women at the expense of other women. For example, if one says “Most women are terrible when it comes to navigating with maps,” they are implying that there is a rule that women are inferior or incompetent in some way. Also, men may use gendered language to imply what is right or good. For example, a male may refer to another male as a “pussy” or may urge him to “man up,” which perpetuates a myth that females are weak.

Gender roles. Many fishing communities and organizations reflect the culture of society, and males typically have greater access to power. Commonly the division of labor in fishing communities is based on gender, which leads to unequal access to benefits of fishing. Gender roles are a source of prejudice and place limits on individuals and their behavior. Rural women face obstacles emanating from a strong patriarchal culture, prejudice, and tyranny rooted in religious traditions, as well as limited control over economic resources and the decision-making process (Deb et al. 2015). In some fishing communities, women fish close to home with little costly equipment in places where fishing may be done in the company of children. In Ghana, women called “Big Mammies” play major roles financing the tuna trade (Drury O’Neill et al. 2018). Gender roles can and do change over time (Gustavsson 2020). For example, in North America, the latter half of the 20th century saw an increase in working wives and mothers and their struggle to balance work and family life.

Sexual harassment. Harassment includes unwanted sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature. The growing sexual harassment problem hinders women’s participation in male-dominated parts of the fisheries value chain as well as the management and science sectors. Many women have been the target of some form of harassment, especially those with less power in the workplace. In a 2013 global survey across scientific disciplines, 64% of respondents reported being subjected to sexual harassment during fieldwork and 20% to sexual assault (Clancy et al. 2014). Among female observers on Alaskan commercial fishing boats, roughly half said they had experienced sexual harassment aboard vessels (Gross 2019). Such inappropriate and sexist behavior and its aftermath can derail a career and close off opportunities for women (Nelson et al. 2017).

Toxic masculinity. The term “toxic masculinity” was coined in the 1980s by Shepherd Bliss to characterize his father’s authoritarian masculinity. Toxic masculinity, sometimes called harmful masculinity, involves cultural pressures for men to behave in a way that corresponds to an old idea of “manliness” that perpetuates dangerous societal standards, such as male domination, homophobia, and aggression. In conversation, a male might respond with “I’m a guy, what do you expect?” Toxic masculinity teaches men that aggression and violence are acceptable solutions to problems. Toxic masculinity is expressed in some connections between environmental degradation and sexual power (Voyles 2021).

Recognizing that these gender issues exist is the first step in examining fishing with a gender lens. It is unacceptable to assume that if I don’t see it, it must not exist. Codes of conduct and rules for enforcement are essential to equal opportunity for all participants. The pervasive nature of these gender issues means that many allies will be needed to support gender equity in fishing and fisheries. These allies recognize that “If I were to remain silent, I’d be guilty of complicity.” Therefore, the message to all is to “See it. Name it. Stop it.”

7.4 Foundational Gender Concepts Apply to Fishing

Many differences exist among individuals and how they fish or do not fish. The problems arise when individual differences translate to differing preferences, privilege, and power (Figure 7.2). Differences mean that individuals display preferences that lead to certain unearned privileges. These privileges of males in fishing and fisheries are often a result of patriarchy where men are dominant figures who hold power. In fishing communities, males have much greater power in the catching and management of fish and occupy positions of power. In these male-dominated situations, males have ready access to resources and maintain differential power, and females are oppressed or their roles discounted. Over time, the oppression is internalized in ways that members of marginalized groups may see themselves as less or inferior. Men—especially middle-aged, middle-class white ones—are lacking in self-awareness of unearned privilege because they have gone through life taking their privileged position for granted (Perry 2017).

In addition to gender, multiple forms of oppression and identity interact to create one’s experience and access to influence and power (Figure 7.3). Therefore, the term “intersectionality” is a useful construct here as it acknowledges that everyone has their own unique experience of discrimination and privilege. Intersectionality is a crucial starting point in discussions and is grounded in social justice (Crenshaw 1989, 1991). Fishing controversies are seldom single-issue struggles. For example, fishing access may be constrained by race, class, language, or disability. Numerous factors, including gendered stereotypes, pedagogy, and science curricula, all conspire against a young woman’s ability to develop a science identity. In small-scale fisheries, gender intersects with issues such as human rights, well-being, food security, and climate change.

Society traditionally regards women as dissimilar to men in most fishing contexts. The difference often leads to societal preferences for men in fishing and may limit participation by women. Women are a minority in many male-dominated sectors of fishing value chains, fisheries management, and fisheries science. Participation by females in sportfishing depends on local culture and its ideas about a woman’s place (Toth and Brown 1997).

Gender socialization refers to the learning of behavior and attitudes considered appropriate for a particular gender. The group’s beliefs, behaviors, language, and policies will influence an individual’s initial involvement, attachment, and commitment. Females in fishing groups were seeking social aspects of fishing, while males were more interested in sport-related aspects (Kuehn et al. 2006).

Question to ponder:

Individuals reveal their sexist attitudes in their beliefs, behavior, and language, whereas institutions reveal sexist biases in established policies. Can you think of sexist beliefs, behaviors, language, or policies related to fishing?

Ecological feminism considers several foundational beliefs to guide our viewing of fishing through a gender lens (Gilligan 1988; Gaard 1993; Gaard and Gruen 1993). Foundational beliefs of feminism include the following:

- Women are oppressed and mistreated.

- The oppression and mistreatment of women is wrong.

- The analysis and reduction of the oppression and mistreatment of women are necessary (but not sufficient) for the creation and maintenance of the kind of individual and communal lives that should be promoted within good societies.

- Because different forms of oppression are intermeshed, the analysis and reduction of any form of oppression, mistreatment, or unjustified domination is necessary for the creation and maintenance of the kind of individual and communal lives that should be promoted within good societies (Cuomo 1998).

Language, practices, and values that lead to oppression of women are similar to those leading to exploitation or degradation of nature. For example, consider the passage from Warren (1994, 37):

Women are described in animal terms as pets, cows, sows, foxes, chicks, serpents, bitches, beavers, old bats, old hens, mother hens, pussycats, cats, cheetahs, bird-brains, and hare-brains. . . . “Mother Nature” is raped, mastered, conquered, mined; her secrets are “penetrated,” her “womb” is to be put into the service of the “man of science.” Virgin timber is felled, cut down; fertile soil is tilled, and land that lies “fallow” is “barren,” useless. The exploitation of nature and animals is justified by feminizing them; the exploitation of women is justified by naturalizing them.

Systematic analysis of gender differences in fishing is lacking, leading to persistence of implicit biases. “Implicit bias” describes when we have attitudes toward people or associate stereotypes with them without our conscious knowledge. Further analysis may help us understand differences in behavior and reveal biases that persist. We must remember that just as all men are not alike, all women are not alike. Yet, the studies done thus far support the conclusion that women experience more constraints to their participation.

Author Ernest Hemingway wrote about the quintessentially masculine image in this story of big game fishing in The Old Man and the Sea. Santiago, the main character, says, “I’ll kill him and all his greatness and his glory. I will show him what a man can do and what a man endures.” This is clearly a male author using masculine language to communicate this—the struggle between him and the fish. Ernest Hemingway and other writers always promoted the idea when they’re fighting these big trophy fish, that they were males and they were referred to as males—an implicit bias. This male bias misinforms us about the biology of fish. Females are more likely to be the larger individuals in many big game species, such as swordfish.

Fishers are a socially and culturally diverse group of people. However, the privilege and power differentials often lead to poor representation of marginalized groups in decision making. Therefore, fishing policies are often inappropriate when viewed with a gender lens (Williams 2008). Fishing and aquaculture policies currently do not collect gender-disaggregated data and do not value all the forms of labor. This leads to gender-blind policies, which may be inappropriate because they do not recognize the difference in motivations or roles (Figure 7.4). Gender-aware policies that take into consideration the gender differences so that better outcomes are achieved use instrumental frames to promote gender equality, whereas other gender-aware policies rely on intrinsic frames of fairness and justice as primary outcomes.

7.5 Towards the Goal of Gender Equality

Dialogues on gender equality in the seafood and fishing industries should be stimulated to create consciousness, to bring information, to share good practices, and to stimulate progressive initiatives. When we take a gender perspective, we look at relationships between women and men to identify where there are differences that generate inequalities, vulnerabilities, fears, and exclusion. Transforming harmful social ideas and practices requires everyone’s collaboration, regardless of their gender.

What prevents women from entering sportfishing? It only takes a single barrier to prevent females from becoming regular participants in fishing. The list below, shared by Betty Bauman of Ladies, Let’s Go Fishing!®, is only a partial list.

Sample Barriers to Participation by Females in Recreational Fishing:

- Husband/boyfriend says fishing is for guys only, won’t take them

- Can’t learn from others on the boat—no time to instruct

- Want to take their kids fishing but nobody knows how

- They have to stay home with kids while husband fishes

- Too early in the morning

- No one else to fish with

- Don’t like touching slimy fish

- Seasickness

- Feeling like “the alien” when entering a tackle shop

- Lack of knowledge and confidence regarding fishing skills (being on the team when you don’t know the game)

- Unable to launch or drive a boat

- Yelling / condescending comments / afraid to ask stupid questions

To encourage participation by females in sportfishing, we need to understand that certain motivations are unique to females. In a survey of licensed anglers in Minnesota in 2000–2001,

- Men reported higher involvement in fishing than women did.

- Women rated motivations related to catching fish for food higher than men did.

- Men rated developing skills and catching trophy fish higher than women did.

- Men agreed more with ethics related to catch-and-release fishing (Schroeder et al. 2006).

Questions to ponder:

In your lifetime, who has had the greatest influence on your behavior and personality? Take the implicit assumption test https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/ , which is a free test designed to allow an individual to identify their own unconscious biases related to gender, race, ethnicity, and obesity. What privileges do you possess due solely to your individual characteristics?

7.6 Examples of Women’s Impact

Sportfishing. Among those who fish for sport, only 27% of U.S. anglers are female (Burkett and Carter 2020). Underrepresentation of females in sportfishing is ironic, as the first publication on fly-fishing, dating from the 15th century, was written by Dame Juliana Berners, entitled Treatyse of Fysshynge with an Angle, a publication that heavily influenced novelty of the sport for European enthusiasts. Though sometimes invisible, women are slowly changing the world of sportfishing by breaking stereotypes. Future growth of sportfishing will rely on female anglers, instructors, and guides. Here I share a few examples on women making a substantial impact through their passion toward fishing. These examples demonstrate women who loved and valued what they did. If the paucity of female role models discourages females from seeing the relevance of fishing to them, these examples should inspire.

Frederick Buller (2013) chronicled the very long list of large Atlantic Salmon caught by female anglers, which are outnumbered 200 to 1 by male salmon anglers. Georgina Ballantine holds the British record for a 64-pound rod-caught Atlantic Salmon from River Tay, Scotland, in 1922 (Figure 7.5). Joan Wulff was introduced to fly-fishing by her father when she was ten and won several fly-fishing accuracy championships before winning the 1951 Fishermen’s Distance competition against all-male competitors. She became the first female spokesperson for Garcia Corporation in 1959 and advocated for women anglers in her writings for Outdoor Life and Rod & Reel. Today, females make up 30% of participants in the sport of fly-fishing (Recreational Fishing and Boating Foundation 2021). Joan Wulff participated in many distance casting events and did trick casting. She snapped a cigarette from the mouth of Johnny Carson on the TV show “Who Do You Trust?” (Fogt 2017). Starting in 1978, Wulff opened a fly-casting school on the Upper Beaverkill River in New York. Her Fly-Casting Techniques, published in 1987, and New Fly-Casting Techniques, published in 2012, are classic guides to learning her techniques. When asked about her favorite fish, she would respond, “Whatever I’m fishing for,” and her favorite place to fish was “Wherever I am.”

Most avid bass anglers can identify Roland Martin, Bill Dance, and Jimmy Houston, who dominated competitive bass fishing in the first decade of Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (B.A.S.S.) and have had TV fishing shows for decades. Kim Bain-Moore began competing in bass tournaments at age 19 and in 2009 became the first woman to compete in the Bassmaster Classic tournament. Only three females have been inducted into the Bass Fishing Hall of Fame. The first was Christine Houston, who organized the first-ever all women’s bass club, the “Tulsa Bass Belles.” But female participation in competitive bass fishing never took off as expected. Fewer that one in five readers of Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, and Bassmaster magazines are female (Carini and Weber 2017).

There are signs of change since Betty Bauman, the founder and CEO of Ladies, Let’s Go Fishing!® created “The No-Yelling School of Fishing.” Baumann realized that women preferred a nonintimidating atmosphere where they could learn fishing techniques (Crowder 2002). Since the first program in 1997, over 8,000 participants have graduated from the Ladies, Let’s Go Fishing! Training. In 2018, the Lady Bass Anglers Association was formed to promote the Women’s Pro Bass Tour. Wild River Press released Fifty Women Who Fish, by Steve Kantner. Many female fishing guides are emerging, as well as fishing resources for female anglers. One indigenous fly-fishing guide, Erica Nelson, became an avid fly fisher, guide, and advocate for inclusive fishing (Aiken 2022).

Subsistence Fishing. Women make up a significant, yet hidden, portion of the subsistence fishing workforce (Ogden 2017). Many times the catches are taken along the shoreline, on foot, or from small nonmotorized boats (Figure 7.6). Yet recent estimates suggest that the catch by women is a substantial contribution, especially to local communities (Harper et al. 2020). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 47% of the 120 million people who earn money directly from fishing and processing are women, while women make up some 70% of those engaged in aquaculture (Montfort 2015).

Catches by women are partially for home consumption or sold to support the household and child-rearing expenses, they are not part of the measured economic output. The work of women in subsistence fishing helps improve their living conditions, educate children, and gain economic independence. In Asia and Africa, many small-scale fisheries also produce dried fish (Figure 7.7). Over 50% of the workforce in fish drying yards of Bangladesh are women from marginalized groups, such as lower castes and refugees (Belton et al. 2018). Women working to process and market dried fish are constrained by gender restrictions that influence their ability to purchase fresh fish (Manyungwa et al 2019). Policy makers and development practitioners throughout the world often overlook the women’s burdens that are not shared by her brothers (Sharma 2014). The hegemony of dominant male fishermen is slowly beginning to crack as contributions of women are demonstrated (Weeratunge et al. 2010; Harper et al. 2012, 2017; Branch and Kleiber, 2017; Frangoudes and Gerrard 2018; Smith and Basorto 2019). Yet, many changes are needed for gender equity in fishing.

Commercial Fishing. Earliest commercial fisheries in North America recruited migrants to work in seasonal fisheries. Only white men engaged in these fisheries, and violence was common as men sought their place or power in commercial fishing industries. In the salmon fisheries that developed on the Columbia River, the fishing culture shifted from a rough, violent masculinity of seasonal labor to one dominated by ethnic patriarchy that emphasized fishing as the principal work for family breadwinners. Women played important if unrecognized roles as bookkeepers, parts runners, and general hands. By the 1970s, technological advancements provided a few openings for women on the boats, but by that time the commercial fisheries had dramatically declined in scope (Friday 2006).

Today, commercial fishing fleets are overwhelmingly male dominated, with fewer than 4% of commercial fishing licenses issued to women in Oregon and Washington states. Yet women contribute to resilient communities by caring for family and maritime households, and increasingly women play a significant role in science, fisheries management, policy, and decision making (Calhoun et al. 2016). The following quote is from a participant in an oral history project:

I used to go to groundfish management team meetings 25 years ago, and if there was one woman scientist in the groundfish management team it was a big deal. And now you see women are the chairs of the groundfish management team. So seeing changes, growth of women in both management and in science. Although I know those areas are still a challenge too. And then the rise of women participating in the decision-making process. (Calhoun et al. 2016)

Fisheries Science. In the early 20th century, research universities were seldom willing to offer women academic positions and a lab of their own. However, some women prevailed despite the discrimination (Brown 1994). I describe experiences and influences of Eugenie Clark and Emmeline Moore, recognizing that there were many other female scientists who were inspirational figures.

Eugenie Clark (1922–2015) was a zoologist at a time when the field was male dominated. Her illustrious career accomplishments are even more impressive when one considers the blatant sexism early in her career. In her first book, Lady with a Spear, she wrote of her expeditions to the West Indies, Hawaii, Guam, Palau, and the Red Sea, as well as early research trials on vision and behavior in gobies, puffers, triggerfishes, and sharks. In an interview, she said, “We had to work extra hard, especially on field trips, to prove we could keep up with males.” Eugenie Clark became a self-taught expert in the art of throwing a cast net and catching fish with both wooden-handled harpoons and spearguns. She pioneered research on behavior of sharks, conducted numerous submersible dives around the world, and founded the Mote Marine Lab before becoming a professor at the University of Maryland. Clark was a productive researcher who made 71 research dives with submersibles, and her many awards and accolades include the Legend of the Sea Award (Staff 2015).

Emmeline Moore (1872–1963) was a pioneering researcher investigating lakes from an ecosystem and landscape perspective (Zatkos 2020). Moore was the first woman scientist employed by the New York Conservation Department (1920–1925) and later led the New York Biological Survey, the most comprehensive watershed study of aquatic resources at the time. She was Chief Aquatic Biologist for New York State from 1932 to her retirement in 1944. Moore was an active member and leader in the American Fisheries Society, being elected as first female president of the organization in 1927. Her research on pond plants, food web dynamics, pollution, and fish parasites helped change the way fish were managed.

7.7 Toward More Inclusive Public Participation in Fisheries

Conventional wisdom for managing fisheries has focused on employment and products that contribute to value of all goods and services. However, mainstream economists (mostly male) tend to focus only on those things measured in monetary terms. Yet, feminist economists argue that many measures of human well-being from fisheries are ignored by prevailing governance systems (Cohen et al. 2019). Furthermore, the “tragedy of the commons” maintained that in trying to serve their own self-interests, individuals end up hurting themselves—and the public good—in the long run. Consequently, government intervention was needed to prevent the collapse.

The pioneering work of Elinor Ostrom demonstrated that human cooperation, self-governance, and sharing allow people to overcome the tragedy of the commons (Ostrom 1990). She argued that there was “no reason to believe that bureaucrats and politicians, no matter how well meaning, are better at solving problems than the people on the spot, who have the strongest incentive to get the solution right.” Her research has led to management of natural resources via comanagement. FAO’s Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (FAO 2015, 2017) is one of the few policy guidelines that addresses the role of gender in fisheries. These guidelines call for equal participation of women and men in organizations and in decision-making processes. Consider the following argument claim for comanagement of fisheries:

Premise: Historically, fisheries decision-making literature focused primarily on stakeholder groups who were mostly comprised of men.

Premise: Environmental knowledge is gendered.

Premise: Who has a voice in community conservation influences how well a group functions and who gains and loses from or is affected by interventions.

Premise: Omitting stakeholders may also obscure the difference between those who have a stake in fish conservation and those who have the ability to act on it.

Premise: Participatory approaches often aim to overcome stakeholder neglect by purposefully including diverse stakeholders.

Normative Claim: Solutions to problems should be built on shared negotiation processes with all stakeholders.

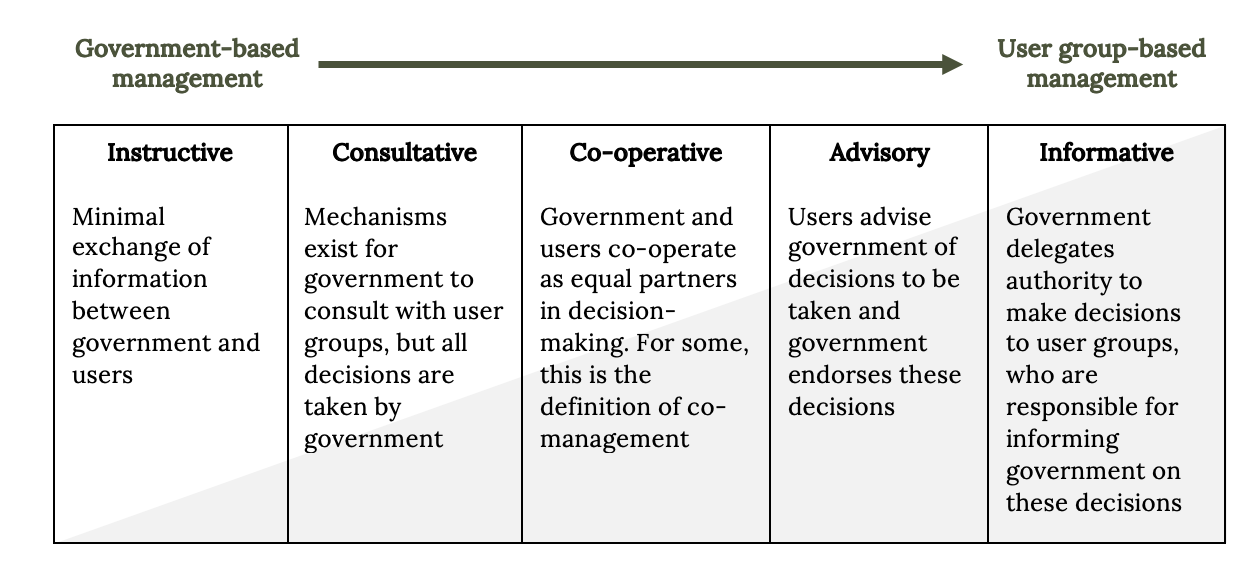

Comanagement of fisheries represents a wide spectrum of user participation. Consider the range of opportunities for participation illustrated (Figure 7.8). Management approaches that consciously and explicitly consider gender and diversity of actors may provide the basis for better fisheries governance (de la Torre-Castro 2019). In simpler cases, participation by fishers is limited and governments are able to effectively manage fisheries with minimal exchange of information. This is sometimes called Decide-Announce-Defend, or DAD for short. The DAD method is not suited for fisheries, where a wide range of technical, social, cultural, and economic factors are influencing the current situation and the various possible alternatives to it, and successful implementation involves a lot of people, and these people are not in an obvious command structure. Governments may provide opportunities for participants to provide input (consultative). Most believe comanagement requires at least a cooperative arrangement where participants are equal participants. In fisheries where staffs of small governments are overwhelmed by the number of fishers who are mobile and can select from many fishing opportunities within a region, governments may choose to allow groups to advise or make management decisions collectively. One example demonstrated that comanagement provided a new source of female income from fisheries and an unprecedented recognition of female participation in fishing activities (Freitas et al. 2020).

Today, there are organizations throughout the world to support equitable participation in fishing. A few examples are listed here:

- Commercial and Subsistence Fishing

- Strength of the Tides: Community organization aiming to support, celebrate, and empower all women, trans, and gender queer people on the water.

- Dried Fish Matters: Goal is to identify the overall contribution of dried fish to the food and nutrition security and livelihoods of the poor and examine how production, exchange, and consumption of dried fish may be improved to enhance the well-being of marginalized groups and actors in the dried fish economy.

- Minorities in Aquaculture: Goal is to educate women of color on the environmental benefits of aquaculture and support them as they launch and sustain their careers in the field, growing the seafood industry and creating an empowering space for women along the way.

- Women in Fisheries Network and other initiatives support women fishing.

- Gender in Aquaculture and Fisheries: Addresses the data gaps and issues faced by women in fisheries.

- Recreational Fishing

- Ladies Let’s Go Fishing: Dedicated to attracting women to fishing and to promoting conservation and responsible angling.

- Angling For All: Encourages fishing companies to sign the Angling for All Pledge that establishes a commitment to addressing racism and inequality throughout a pledgee’s internal culture, consumer-facing behaviors, and broader community.

- Brown Folks Fishing: Cultivates the visibility, representation, and inclusion of people of color in fishing and its industry.

- United Women on the Fly: Committed to building an inclusive community that educates, provides resources, encourages, and connects anglers from all backgrounds into the sport of fly-fishing.

Today we are regendering many types of work and leisure activities, including fishing. The significant challenges that we face in fish conservation at home and abroad will require input from all. Rather than propagating stereotypes of fishing activities, we need to explore the participation across gender and other differences so we can do a better job evaluating outcomes of conservation for the well-being of all humans.

Women and men have significantly different approaches and views on public policy issues, which means that women’s voices and those of minorities need to be heard.

—Janet Yellen

Profile in Fish Conservation: Danika L. Kleiber, PhD

Danika Kleiber is a fisheries social scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) based in Hawai‘i. She was always interested in blending her interests in fisheries biology and feminism and earned a degree in biology and women studies at Tufts University.

Today, her research specialty focuses on issues of equity and the intersection of gender and natural resources, in particular socioecological research approaches to small-scale fisheries management. Her research has uncovered some hidden relations between gender, food security, and participatory governance.

In a study for her dissertation, Kleiber characterized the participation of women in small-scale fisheries from 106 case studies from around the world. This landmark study revealed reasons why women are seldom adequately studied in fisheries. In some cases, it is considered culturally unacceptable for women to fish. In other cases, analysts used very limited definitions of what counts as fishing. In fact, in some languages, such as Greek and Greelandic, there is no female equivalent for the term “fishermen.” These and other gender biases reinforced the clear need for fisheries scientists to embrace gender approaches and appreciate women in fishing as parts of an interdisciplinary ecosystem approach.

Kleiber’s studies of small-scale fisheries demonstrated the scope and economic impact of women in a variety of roles. Gleaning was often overlooked by previous studies. But this hand collection of invertebrates from shallow intertidal water is the main livelihood for many rural women. To advance fisheries management, Kleiber is pioneering studies of social impacts of proposed fisheries management measures on fishing communities. Social impact assessment tracks many indicators beyond catch and revenues and recognizes that fishing also contributes to culture and social cohesion of island communities.

Key Takeaways

- Women are involved in all aspects of the fishing industry, including skinning, drying, curing, salting, processing, and marketing seafood.

- Rights, equity, and justice are mainstream principles of good fisheries governance.

- Women’s role in fishing or fisheries is often overlooked in decision making for cultural reasons.

- Foundational concepts of ecofeminism and intersectionality are useful constructs for analyzing fisheries gender issues.

- Fisheries management policies are set by governance bodies that exclude women.

- Intersectionality is a crucial starting point in all discussions and is grounded in social justice.

This chapter was reviewed by Kafayat Fakoya.

Long Descriptions

Figure 7.1: Government, Institutions, NGOs, & Donors, provide assets and services give support to fisheries governance. Chart splits showing, left: fisheries governance gives greater support in traditional roles to (male symbol) in access, ownership, rights; leads to control harvest, more influence in governance; right: fisheries governance gives less support in traditional roles (female symbol) with limited access, no ownership, limited rights; leads to conduct post harvest, less influence in governance. Both lines lead to lower representation in decision making increases community vulnerability. Jump back to Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.3: Intersectionality displays how social identities intersect with one another and are wrapped in systems of power with overlapping circles of a spirograph, including 1) race, 2) ethnicity, 3) gender identity, 4) class, 5) language, 6) religion, 7) ability, 8) sexuality, 9) mental health, 10) age, 11) education, 12) body size, and many more. Quote by Kimberle Crenshaw reads, “intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it locks and intersects. It is the acknowledgement that everyone has their own unique experiences of discrimination and privilege.” Jump back to Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.8: Range of co-management arrangements from government-based management to user group-based management. From left, 1) instructive, minimal exchange of information between government and users; 2) consultative, mechanisms exist for government to consult with user groups, but all decisions are taken by government; 3) co-operative, government and users co-operate as equal partners in decision-making. For some this is the definition of co-management; 4) advisory, users advise government of decisions to be taken and government endorses these decisions; 5) informative, government delegates authority to make decisions to user groups, who are responsible for informing government on these decisions. Jump back to Figure 7.8.

Figure References

Figure 7.1: Conventional fisheries governance gives greater support for traditional roles of males leading to lower representation of females in decision making. Adapted under fair use from A Review of Women’s Access to Fish in Small-Scale Fisheries, by Angela Lentisco and Robert Ulric Lee, 2015 (https://www.fao.org/3/i4884e/i4884e.pdf). Includes “Male,” by Heri Sugianto, 2018 (Noun Project license, https://thenounproject.com/icon/male-1745485/), and “Female.” by Maurizio Fusillo, 2012 (Noun Project license, https://thenounproject.com/icon/female-3446/).

Figure 7.2: The progression of gender influences begins with difference and illustrates a common pattern by which power is accrued by individuals who embody certain characteristics. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.3: Intersectionality is a powerful framework that acknowledges that everyone has unique experiences of discrimination and privilege. Sylvia Duckworth. 2020. Used with permission from Sylvia Duckworth. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.4: Policies may be gender blind or gender aware, and gender-aware policies may be instrumental or intrinsic. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.5: Georgina Ballantine holds the British record for a 64-pound rod-caught salmon from River Tay, Scotland in 1922. Photo by Raeburn Studio. Illustrated London News, “A woman breaks the record for tay salmon: A 64-pounder.” 2022. Public Domain.

Figure 7.6: Rana Tharu women go fishing in southwest Nepal. Yves Picq. 2004. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:N%C3%A9pal_rana_tharu1818a_Crop.jpg.

Figure 7.7: Woman selling dried fish at fish market in Cambodia. McKay Savage. 2008. CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cambodia_08_-_036_-_markets_-_dried_fish_for_sale_(3198824843).jpg.

Figure 7.8: Spectrum of comanagement showing increasing participation of users from government-based to user group–based management. Kindred Grey. 2022. Adapted under fair use from “Fisheries co-management: a comparative analysis,” by Sevaly Sen and Jesper Raakjaer Nielsen, 1996 (https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-597X(96)00028-0).

Figure 7.9: Danika L. Kleiber, PhD. Used with permission from Danika L. Kleiber. CC BY 4.0.

Text References

Aiken, M. 2022. “I identify as an angler”: meet Erica Nelson, a female, indigenous fly fishing guide. New York Times, February 19, 2022. https://www.awkwardangler.com/blog/nytimes.

Ameyaw, A. B., A. Breckwoldt, H. Reuter, and D. W. Aheto. 2020. From fish to cash: analyzing the role of women in fisheries in the western region of Ghana. Marine Policy 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103790.

Belton, B., M. A. R. Hossain, and S. H. Thilsted. 2018. Labour, identity and wellbeing in Bangladesh’s dried fish value chains. Pages 217–241 in D. Johnson, T. G. Acott, N. Stacey, and J. Urquhart, editors, Social wellbeing and the values of small-scale fisheries, Springer, New York.

Bennett, E. 2005. Gender, fisheries and development. Marine Policy 29:451–459.

Branch, T. A., and D. Kleiber. 2015. Should we call them fishers or fishermen? Fish and Fisheries 18(1):114–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12130.

Brown, P. S. Early women ichthyologists. Environmental Biology of Fishes 41:9–30.

Bull, J. 2009. Watery masculinities: fly-fishing and the angling male in the south west of England. Gender, Place & Culture 16(4):445–465.

Buller, F. 2013. A list of large Atlantic Salmon landed by the ladies. American Fly Fisher 39(4):2–21.

Burkett, E., and A. Carter. 2020. It’s not about the fish: women’s experiences in a gendered recreation landscape. Leisure Sciences 44(7):1013–1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1780522.

Calhoun, S., F. Conway, and S. Russell. 2016. Acknowledging the voice of women: implications for fisheries management and policy. Marine Policy 74:292–299.

Campbell, S. J., R.Jakub, A.Valivia, H. Setiawan, A. Setiawan, C. Cox, A. Kiyo, Darman, L. F. Djafar, E. de la Rosa, W. Suherfian, A. Yuliani, H. Kushardanto, U. Muawana, A. Rukma, T. Alimi, and S. Box. 2021. Immediate impact of COVID-19 across tropical small-scale fishing communities. Ocean & Coastal Management 200:105485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105485.

Carini, R. M., and J. D. Weber. 2017. Female anglers in a predominantly male sport: portrayals in five popular fishing-related magazines. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 52(1):45–60.

Clancy, K. B., R. G. Nelson, J. N., Rutherford, and K. Hinde. 2014. Survey of academic field experiences (SAFE): trainees report harassment and assault. PloS ONE 9(7):e102172.

Clark, E. 1951. Lady with a spear. Harper Brothers, New York.

Cohen, P. J., E. H. Allison, N. L. Andrew, J. Cinner, L. S. Evans, M. Fabinyi, L. R. Garces, S. J. Hall, C. C. Hicks, T. P. Hughes, S. Jentoft, D. J. Mills, R. Masu, E. K. Mbaru, and B. D. Ratner. 2019. Securing a just space for small-scale fisheries in the blue economy. Frontiers in Marine Science 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00171.

Crenshaw, K. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989(1), Article 8. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

Crenshaw, K. 1991. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43:1241–1299.

Crowder, R. 2002. Check your fly: tales of a woman fly fisher. Canadian Woman Studies 21(3):162–165.

Cuomo, C. 1998. Feminism and ecological communities: an ethic of flourishing. Routledge, New York.

Deb, A. K., C. E. Haque, and S. Thompson. 2015. “Man can’t give birth, woman can’t fish”: gender dynamics in the small-scale fisheries of Bangladesh. Gender, Place & Culture 22(3):305–324.

de la Torre-Castro, M. 2019. Inclusive management through gender consideration in small-scale fisheries: the why and the how. Frontiers in Marine Science 6:156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00156.

Drury O’Neill, E., N. K. Asare, and D. W. Aheto. 2018. Socioeconomic dynamics of the Ghanaian tuna industry: a value-chain approach to understanding aspects of global fisheries. African Journal of Marine Science 40:303–313.

Fogt, J. 2017. Virtuoso. Anglers Journal, May 12. Accessed June, 21, 2019, at https://www.anglersjournal.com/freshwater/virtuoso.

FAO. 2015. Voluntary guidelines for securing sustainable small-scale fisheries in the context of food security and poverty eradication. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

FAO. 2017. Towards gender-equitable small-scale fisheries governance and development: a handbook. (In support of the implementation of the Voluntary guidelines for securing sustainable small-scale fisheries in the context of food security and poverty eradication, by Nilanjana Biswas.) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

Frangoudes, K., and S. Gerrard. 2018. (En)Gendering change in small-scale fisheries and fishing communities in a globalized world. Maritime Studies 17:117–124.

Friday, C. 2006. White family fishermen, skill, and masculinity. The Oregon History Project. Available at: https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/white-family-fishermen-skill-and-masculinity/#.YhkBji-B1qs.

Freitas, C. T., H. M. V. Espírito-Santo, J. V. Campos-Silva, C. A. Peres, and P. F. M. Lopes. 2020. Resource co-management as a step towards gender equity in fisheries. Ecological Economics 176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106709.

Gaard, G., editor. 1993. Ecofeminism: Women, animals, and nature. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Gaard, G., and L. Gruen. 1993. Ecofeminism: toward global justice and planetary health. Society and Nature 2:1–35.

Gilligan, C. 1988. Mapping the moral domain: a contribution of women’s thinking to psychological theory and education. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Grace, R. NOAA is trying to encourage more observers to report sexual harassment. 2019. Alaska Public Media, June 5. Accessed January 12, 2023, at https://alaskapublic.org/2019/06/05/noaa-is-trying-to-encourage-more-observers-to-report-sexual-harassment/.

Gustavsson, M. 2020. Women’s changing productivity practices, gender relations and identities in fishing through critical feminization perspective. Journal of Rural Studies 78:36–46.

Harper, S., M. Adshade, V. W. Y. Lam, D. Pauly, and U. R. Sumaila. 2020. Valuing invisible catches: estimating the global contribution by women to small-scale marine capture fisheries production. PLoS ONE 15(3):e0228912. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228912.

Harper, S., C. Grubb, M. Stiles, and U. R. Sumaila. 2017 Contributions by women to fisheries economies: insights from five maritime countries. Coastal Management 45(2):91–106.

Harper, S., D. Zeller, M. Hauzer, D. Pauly, and U. R. Sumaila. 2012. Women and fisheries: contribution to food security and local economies. Marine Policy 39: 56–63. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2012.10.018.

Herbst, P. H. 2001. Wimmin, wimps & wallflowers: an encyclopedic dictionary of gender and sexual orientation bias in the United States. Intercultural Press, Yarmouth, ME.

Jones, J. M. 2021. LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup, February 24. Available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx.

Kleiber, D., K. Frangoudes, H. T. Snyder, A. Choudhury, S. M. Cole, K. Soejima, C. Pita, A. Santos, C. McDougall, H. Petrics, and M. Porter. 2017. Promoting gender equity and equality through the small-scale fisheries guidelines: experiences from multiple case studies. Pages 737–759 in S. Jentoft, R. Chuenpagdee, Barrag´an-Paladines, editors, The small-scale fisheries guidelines, Springer, Cham, NY.

Kleiber, D., L. M. Harris, and A. C. J. Vincent. 2015. Gender and small-scale fisheries: a case for counting women and beyond. Fish and Fisheries 16(4):547–562.

Kleiber, D., L. M. Harris, and A. C. J. Vincent. 2018. Gender and marine protected areas: a case study of Danajon Bank, Philippines. Maritime Studies 17(2):163.

Kolan, M., and K. S. TwoTrees. 2014. Privilege as practice: a framework for engaging with sustainability, diversity, privilege and power. Journal of Sustainability Education 7:1–13.

Kuehn, D. M., C. P. Dawson, and R. Hoffman. 2006. Exploring fishing socialization among male and female anglers in New York’s eastern Lake Ontario area. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 11(2):115–127.

Lawless, S., P. J. Cohen, S. Mangubhai, D. Kleiber, and T. H. Morrison. 2021. Gender equality is diluted in commitments made to small-scale fisheries. World Development 140:105348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105348.

Lopez-Ercilla, I., M. J. Espinosa-Romero, F. J. F. Rivera-Melo, S. Fulton, R. Fernández, J. Torre, A. Acevedo-Rosas, A. J. Hernández-Velasco, and I. Amador. 2021. The voice of Mexican small-scale fishers in times of COVID-19: impacts, responses, and digital divide. Marine Policy 131:104606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104606.

Mallett, R. K., T. E. Ford, and J.A. Woodzicka. 2016. What did he mean by that? Humor decreases attributions of sexism and confrontation of sexist jokes. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 75(5-6):272–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0605-2.

Manyungwa, C. L., M. M. Hara, and S. K. Chimatiro. 2019. Women’s engagement in and outcomes from small-scale fisheries value chains in Malawi: effects of social relations. Maritime Studies 8:1–11.

Merwin, J. 2010. Merwin: study says most women don’t like pink fishing gear. Field & Stream, 24 May. Available at: https://www.fieldandstream.com/blogs/bass-fishing/2010/05/merwin-study-says-most-women-dont-pink-fishing-gear/. Accessed June 20, 2019.

Miles-McLean, H., M. Liss, M. J. Erchull, C. M. Robertson, C. Hagerman, M. A. Gnoleba, and L. J. Papp. 2015. “Stop looking at me!” Interpersonal sexual objectification as a source of insidious trauma. Psychology of Women Quarterly 39(3):363–374.

Monteith, M., M. Burnes, and L. Hildebrand. 2019. Navigating successful confrontations: What should I say and how should I say it? Pages 225–248 in R. K. Mallett and M. J. Monteith, editors, Confronting prejudice and discrimination: the science of changing minds and behaviors. Academic Press, Cambridge, MA.

Montfort, M. C. 2015. The role of women in the seafood industry. Globefish Research Program, vol. 119. FAO, Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/a-bc014e.pdf.

Nelson, R. G., J. N. Rutherford, K. Hinde, and K. B. Clancy. 2017. Signaling safety: characterizing fieldwork experiences and their implications for career trajectories. American Anthropologist 119(4):710–722.

Ogden, L. E. 2017. Fisherwomen—The uncounted dimension in fisheries management: shedding light on the invisible gender. BioScience 67(2):111–117.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Perry, G. 2017. The Descent of Man. Penguin, New York.

Recreational Fishing and Boating Foundation. 2020. 2020 Special report on fishing. Recreational Fishing and Boating Foundation, Alexandria, VA. Available at: https://www.takemefishing.org/getmedia/eb860c03-2b53-4364-8ee4-c331bb11ddc4/2020-Special-Report-on-Fishing_FINAL_WEB.pdf.

Sáez, G., M. Alonso-Ferres, M. Garrido-Macías, I. Valor-Segura, and F. Expósito. 2019. The detrimental effects of sexual objectification on targets’ and perpetrators’ sexual satisfaction: the mediating role of sexual coercion. Frontiers in Psychology 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02748.

Santos, A. 2015. Fisheries as a way of life: gendered livelihoods, identities and perspectives of artisanal fisheries in eastern Brazil. Marine Policy 62: 279–288.

Sarasota Herald-Tribune. 2015. Timeline: Eugenie Clark’s life and work. February 25. https://www.heraldtribune.com/story/news/2015/02/26/timeline-eugenie-clarks-life-and-work/29301086007/.

Schroeder, S. A., D. C. Fulton, L. Currie, and T. Goeman. 2006. He said, she said: gender and angling specialization, motivations, ethics, and behaviors. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 11(5):301–315.

Sharma, R. 2014. Teach a woman to fish: overcoming poverty around the globe. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Smith, H., and X. Basurto. 2019. Defining small-scale fisheries and examining the role of science in shaping perceptions of who and what counts: a systematic review. Frontiers in Marine Science 6:236. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00236.

Thompson, P. 1985. Women in the fishing: the roots of power between the sexes. Comparative Studies in Society and History 27:3–32.

Tilley, A., A. Burgos, A. Duarte, J. dos Reis Lopes, H. Eriksson, and D. Mills. 2020. Contribution of women’s fisheries substantial, but overlooked, in Timor-Leste. Ambio 50:113–124.

Toth, J. F., Jr., and R. B. Brown. 1997. Racial and gender meanings of why people participate in recreational fishing. Leisure Sciences 19:129–146.

Voyles, T. B. 2021. Toxic masculinity: California’s Salton Sea and the consequences of manliness. Environmental History 26:127–141.

Warren, K. J., editor. 1994. Ecological feminism. Routledge, New York.

Weeratunge, N., K. A. Snyder, and C. P. Sze. 2010. Gleaner, fisher, trader, processor: understanding gendered employment in fisheries and aquaculture. Fish and Fisheries 11(4):405–420.

Welch, L. 2019. Fisher vs. fisherman: What do they prefer to be called? Alaska Fish Radio, December 31. Available at: https://www.seafoodnews.com/Story/1204395/Fisher-vs-Fisherman-What-Do-They-Prefer. Accesssed May 31, 2023.

Williams, M. J. 2008. Why look at fisheries through a gender lens? Development 51:180–185.

Woodzicka, J. A., R. K.Mallett, and K. J. Melchiori. 2020. Gender differences in using humor to respond to sexist jokes. Humor 33(2):219–238. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2019-0018.

Woodzicka, J. A., and J. J. Good. 2021. Strategic confrontation: examining the utility of low stakes prodding as a strategy for confronting sexism. Journal of Social Psychology 161(3):316–330.

Woskie, L., and C. Wenham. 2021. Do men and women “lockdown” differently? Examining Panama’s COVID-19 sex-segregated social distancing policy. Feminist Economics 27(1-2):327–344.

Zatkos, L., C. A. Murphy, A. Pollock, B. E. Penaluna, J. A. Olivos, E. Mowids, C. Moffitt, M. Manning, C. Linkem, L. Holst, A. B. Cárdenas, and I. Arismendi. 2020. AFS roots: Emmeline Moore, all things to all fishes. Fisheries 45(8):435–443.

Leadership or dominance, especially by one country or social group over others

Method and practice of teaching, especially as an academic subject or theoretical concept

Separated into its component parts

Belonging naturally or essential