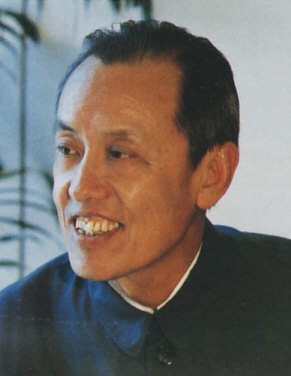

Wu Rukang (1916-2006)

Matthew Goodrum

Wu Rukang (吴汝康) (before 1967 his name was transliterated as Woo Ju-Kang) was born on 19 February 1916 in Wujin County, Jiangsu Province, in eastern China. His father was an elementary school principle. Wu completed a BS degree in biology from National Central University (later renamed Nanjing University) in Nanjing in 1940. Shortly thereafter Wu Dingliang (Woo Ting-Lian), the director of the Anthropology section of the Institute of History and Philology (歷史語言研究所), which was part of the Academia Sinica, hired Wu to work with him as an intern at the Institute. The Institute of History and Philology had been forced to relocate to Kunming, in Yunnan Province, because of the war with Japan. Wu Rukang worked with Wu Dingliang from 1940 to 1942, studying human skeletons and conducting field surveys on the different ethnic groups in Guizhou Province. From 1942 to 1944, Wu was a lecturer at Guizhou University but left to become assistant researcher in the newly established preparatory office of the Institute of Physical Anthropology, part of the Academia Sinica, where he worked from 1944 to 1946.

In 1946, Edmund V. Cowdry, an American who taught anatomy at the Peking Union Medical College from 1917 to 1921 before joining the faculty at the Washington University School of Medicine, arranged for Wu Rukang to travel to the United States to study at the Washington University School of Medicine, in St. Louis, Missouri. After obtaining his Master’s degree in 1947, Wu completed his Ph.D. in physical anthropology under the supervision of Mildred Trotter in 1949 with a dissertation titled “Ossification, Growth and Variation of the Human Maxilla and Palate Bone.” As part of his research, Wu spent the summer of 1948 studying paleoanthropology under the direction of T. Dale Stewart at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. In the autumn of 1949, Wu returned to China, but his return was complicated by the break in diplomatic relations between the newly established People’s Republic of China and the United States, so he had to travel first to Taiwan and then secretly cross to the mainland.

Upon his return, Wu joined the faculty of the Dalian Medical College where he served as a professor and the director of the Department of Anatomy. From 1953 to 1956, he also worked as an adjunct researcher in the Laboratory of Vertebrate Paleontology (古脊椎动物研究室). The Laboratory originated from the Cenozoic Research Laboratory, which was created in 1929 in conjunction with the excavations at Zhoukoudian that produced the famous Homo erectus (Peking Man) fossils. In 1953 the Cenozoic Research Laboratory was reorganized into the Laboratory of Vertebrate Paleontology, affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and in 1960 the Laboratory was renamed the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (古脊椎动物与古人类研究所). Excavations had recently reopened at Zhoukoudian and professor Yang Zhongjian, who later became director of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, invited Wu to examine some of the new fossils found there. It is from this point that Wu’s career became devoted to paleoanthropology research. In 1956, he left the Dalian Medical College to become a full time researcher at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (at that time it was still called the Laboratory of Vertebrate Paleontology). Significantly, Wu also joined the Communist Party of China in 1957.

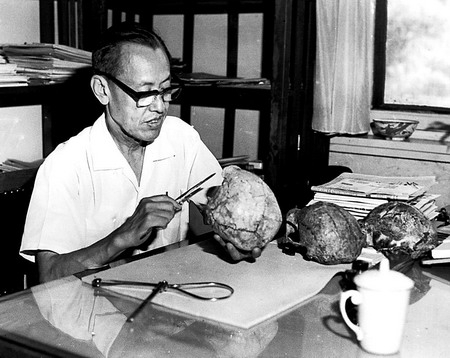

During his long career at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Wu studied many important fossils relating to primate and especially human evolution. Construction projects undertaken by the new government as well as the resumption of scientific excavations produced a wealth of new ape and hominid specimens. Wu studied Dryopithecus fossils found in 1956-7 in Yunnan province and a cache of fossils found in 1975 at Lufeng, in Yunnan province, that were originally thought to represent Sivapithecus and Ramapithecus. Wu examined these fossils and in 1987 he proposed they be placed in a new genus called Lufengpithecus (Wu 1987). Wu became particularly known for his comprehensive analysis of Gigantopithecus fossils, which led to an important monograph titled The Mandibles and Dentition of Gigantopithecus (Wu 1962).

In 1949 excavations resumed at Zhoukoudian, and soon new fossils were found at the site. Wu and his colleague Jia Lanpo examined new Homo erectus teeth and limb bones found at Zhoukoudian between 1949 and 1951 (Wu and Jia 1954). Wu then published a description of a Homo erectus mandible found at Zhoukoudian in 1958 (Wu and Zhao 1959). Excavations also began to discover Homo erectus fossils in other parts of China. Wu studied the Homo erectus mandible, found in 1963, and the cranial and facial bones found in 1964 in Lantian County, Shaanxi Province, during excavations conducted by the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (Wu 1964; 1966). These two specimens came to be called Lantian Man and are thought to be older than the specimens from Zhoukoudian. Wu also studied the Homo erectus partial cranium excavated from Longtan Cave in Hexian County, Anhui Province in 1980–81 (Wu and Dong 1982).

The renewed excavations also unearthed ancient Homo sapiens fossils from the Paleolithic. Early in his career, Wu and Peng Ruce examined a Homo sapiens partial cranium found at Maba, in Guangdong Province in 1958 (Wu and Peng 1959). Then in 1984, students from Peking University under the direction of Professor Zun’e Lu excavated a partial human skeleton from a collapsed limestone cave near Sitian Village, in Liaoning Provence. The so-called Jinniushan skeleton is thought to be 200,000 years old and displays a combination of Homo erectus and Homo sapiens features and is considered to be archaic Homo sapiens. Wu and his assistant Zhao Zongyi reconstructed the cranium of the specimen and published a description of it in 1988 (Wu 1988a).

Wu, like many of his Chinese colleagues, supported what is called the Multiregional Hypothesis. He argued that Homo erectus populations in Asia evolved into the modern human populations of those areas (Wu and Lin 1983). The opposing theory is the Out of Africa Hypothesis, which argues that Homo erectus became extinct in Asia and the Homo sapiens that migrated out of Africa into Asia are the ancestors of modern Asian peoples. In 1988 Wu published a paper where he proposed the creation of a new discipline called neoanthropology. While paleoanthropology is the study of hominid evolution, neoanthropology would focus specifically on the physical anthropology of modern Homo sapiens (Wu 1988b). By this time, Wu was one of the most important paleoanthropologists in China. He served as the deputy director of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology from 1977 to 1983. In addition, he served as the vice chairman of the Chinese Society of Anatomical Sciences from 1970 to 1978, and then as its chairman from 1978 to 1986. In 1980, he was elected academician of the Academic Divisions of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In 1982, he founded the journal Acta Anthropologica Sinica, which focuses on paleoanthropology and physical anthropology in China.

Wu died in Beijing on 31 August 2006.

Selected Bibliography

Wu Rukang and Jia Lanpo, “New Discoveries of Sinanthropus pekinensis in Choukoutien.” Acta Paleontologica Sinica 2 (1954): 267–288.

Wu Rukang and Zhao Zikuei. “New Discovery of Sinanthropus Mandible from Choukoutien.” Vertebrata PalAsiatica 3 (1959): 169–172.

Wu Rukang and Peng Ruce. Fossil Human Skull of Early Paleoanthropic Stage Found at Mapa, Shaoquan, Kwantung Province. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 3 (1959): 176-182.

巨猿下頜骨和牙齒化石The Mandibles and Dentition of Gigantopithecus. (Palaeontologia sinica, New ser. D: 11), 1962.

“Mandible of the Sinanthropus-Type Discovered at Lantian, Shensi.” Vertebrata PalAsiatica 1(1964a): 1–12.

“Mandible of Sinanthropus lantianensis.” Current Anthropology 5 (1964b): 98–102

“The Hominid Skull of Lantian, Shensi.” Vertebrata PalAsiatica 10 (1966):1-22.

“Palaeoanthropology in the New China.” In L. K. Koenigsson (ed.). Current Arguments on Early Man. Pp. 182–206. London: Pergamon Press, 1980.

Wu Rukang and Dong, Xingren. “Preliminary Study of Homo erectus Remains from Hexian, Anhui.” Acta Anthropologica Sinica 1 (1982): 2-13.

Recent Advances of Chinese Palaeoanthropology. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1982.

Wu Rukang and Lin Shenglong. “Peking Man.” Scientific American 248 (1983): 78–86.

北京猿人遺址综合硏究 [Multi-disciplinary Study of the Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian.] Beijing, 1985.

“A Revision of the Classification of the Lufeng Great Apes.” Acta Anthropologica Sinica 6 (1987): 265–271.

“The Reconstruction of the Fossil Human Skull from Jinniushan, Yinkou, Liaoning Province and its Main Features.” Acta Anthropologica Sinica 7 (1988a): 97-101.

“Paleoanthropology and Neoanthropology.” International Social Science Journal 116 (1988b): 265-270.

Wu Rukang, Wu Xinzhi, and Zhang Senshui, 中国远古人类 [Early Humankind in China]. Beijing: Ke xue chu ban she: Xin hua shu dian Beijing fa xing suo fa xing, 1989.

南京直立人 [Homo erectus from Nanjing.] Nanjing: Jiangsu ke xue ji shu chu ban she, 2002.

Secondary Sources

Frank Spencer, “Wu Rukang (1916-).“ In Frank Spencer (ed.) History of Physical Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. 2 vols. Vol. 2, pp. 1118-1120. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997.

Wu Xinzhi, “Wu, Rukang.” In Claire Smith (ed.), Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Pp. 7920-7921. Springer, New York, 2014.

Li Luyang, 吴汝康传 [Biography of Wu Rukang]. Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific and Technological Education Publishing House, 2004.

Wu Xinzhi, “Wu Rukang,” in W. Qianjin & H. Yanhong (eds.), Outstanding Persons of Chinese Academy of Sciences: 546-549. Beijing: Science Press, 2010.

* I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Lo Kuan-Hung and Shih Po-Jen in translating Chinese sources.