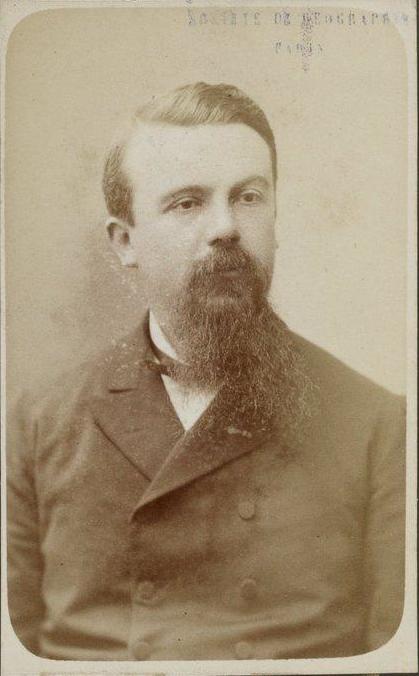

Ernest-Théodore Hamy (1842-1908)

Matthew Goodrum

Théodore-Jules-Ernest Hamy (better known as Ernest-Théodore Hamy) was born on 22 June 1842 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, a town in northern France near the border with Belgium. His father, Théodore-Auguste Hamy, studied in Paris where he attended courses at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). He became a pharmacist in Boulogne-sur-Mer and passed his interest in the natural sciences to his son. Hamy’s mother, Louise Marie Julie Isaac, descended from a Flemish family that immigrated to France in the seventeenth century. Several members of her family were distinguished painters and the young Hamy also displayed artistic talent. Due to his mother’s poor health and early death, when Hamy was only seven years old his father sent him to Catholic boarding schools where he excelled. When he was a student at the Institution Haffreingue in 1857 one of Hamy’s teachers, the amateur archaeologist Daniel Haigneré, led a group of students to his excavation of the tombs in the Merovingian cemetery at Pincthun and Hamy was given the responsibility of drawing the artifacts collected.

Hamy pursued his secondary education in Paris where he obtained a baccalaureate in letters in 1860 and a baccalaureate in the sciences in 1861. He decided to study medicine at the Faculty of Medicine in Paris and interned at the Salpêtrière under the guidance of Jean-Martin Charcot. There he met the French physician, neurologist, and anthropologist Paul Broca in 1864. As a result of this meeting Hamy became an extern at the Hôpital Saint-Antoine under Broca. Since Hamy was interested in anthropology, Broca invited him to become an assistant at the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (Anthropology Society of Paris). The science of anthropology was professionalizing at this time and Broca had established the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris in 1959 to promote anthropological research. One of Hamy’s first duties at the Society was to organize the human skulls collected during the excavation of the cemeteries at the new Hôtel Dieu near Notre Dame for the Society’s museum and he was also tasked with compiling the first catalogue of the Society’s collections. Hamy gained further experience when he participated in archaeological excavations, in 1864, of the Merovingian cemetery at Hardenthun (Pas-de-Calais) conducted by Daniel Haigneré, Hamy’s former teacher at the Institution Haffreingue. An important result of these excavations was the collection of human skeletons.

During this time Hamy also took courses at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle on osteology with Henri Milne-Edwards and prehistory with Edouard Lartet. Hamy was intrigued by the recent discovery of flint artifacts found with extinct animal fossils in glacial deposits, which indicated that humans lived during the Pleistocene. Geologists and archaeologists throughout Europe were uncovering similar artifacts and this encouraged Hamy to look for Ice Age artifacts near his hometown. Hamy and his friend Henri-Émile Sauvage, an amateur geologist and paleontologist who was honorary director of the Station Aquicole in Boulogne-sur-Mer and curator of the local municipal museum, excavated the Quaternary deposits around Boulogne-sur-Mer where they found stone tools. This early excursion into Paleolithic archaeology led to the publication of a book titled Étude sur les terrains quaternaires du Boulonnais et sur les débris d’industrie humaine qu’ils renferment (1866). That same year, Hamy became a member of the Société Académique du Boulonnais.

Hamy became a member of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris in 1867 and his research into anthropology expanded. He was invited to study the Egyptian mummies and skulls collected by French Egyptologist François-Auguste-Ferdinand Mariette and sent by Isma’il Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt, as part of the preparation for the 1867 Exposition Universelle held in Paris. Meanwhile Hamy completed his thesis on the human intermaxillary bone in the normal and pathological state (L’os intermaxillaire de l’homme à l’état normal et pathologique) in 1868. Hamy’s thesis received an award from the Faculty of Medicine as well as the Prix Godard from the Société Anatomique de Paris in 1869.

Broca appointed Hamy to the position of préparateur and chef de travaux at the Laboratoire d’Anthropologie at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in 1868. The following year, the Ministry of Instruction authorized Hamy to teach a course on anthropology at the amphitheater on the rue Gerson at the Sorbonne. The success of this course led to a course on Tertiary humans in the Americas which he taught in 1870. In 1869 Hamy traveled to Egypt for three months with Broca, the anthropologist Armand de Quatrefages, and the archeologist François Lanormant as part of the official delegation celebrating the opening of the Suez Canal. While there he traveled to see the ruins at Thebes and Abydos. More significantly, Hamy and Lenormant were able to collect more than a hundred Paleolithic flint axes and knives from the Nile basin (Hamy 1869b), although many archaeologists doubted the geologic age of these artifacts at the time.

Following the excavations of Henri de Longuy, Edouard Loydreau, and Jules Martin at Santenay in eastern France, Edouard Lartet directed Hamy to excavate some caverns in the Dheune valley, near Santenay, in 1870. Hamy and Henri de Longuy worked there for several years excavating the bone breccias of several caves including Pointe du Bois, grotte de Saint-Jean, grotte de Saint-Aubin, and grotte de la Roche-Fendue du Bois de la Fée where they found Neolithic artifacts and two human skeletons (Longuy 1883; Longuy and Sauvageot 1884). They sent animal fossils collected in the caves to paleontologist Albert Gaudry at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle and members of the Société Géologique de France (Geological Society of France) made an excursion to Santenay on 25 August 1876. In addition to these investigations, Hamy also excavated the dolmens at Mount Julliard, located between Santenay and Nolay, as well as the necropolises of the Chassey camp. Hamy’s scientific activities were interrupted in 1870 because of the Franco-Prussian war. While Paris was under siege by Prussian soldiers Hamy served as a surgeon-major in the Troisième Légion of the national guards of Pas-de-Calais.

In 1872 Hamy left his position at the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris and became aide-naturaliste (assistant) to Armand de Quatrefages, who held the chair of anthropology at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. By this time, he was deeply involved in anthropological research. In June 1870, Hamy had arranged an agreement with the Paris publisher Jean-Baptiste Baillière to produce a book on the human races, including prehistoric humans. As part of this project, over the next decade Hamy worked with Quatrefages to examine many of the human fossils recently found in Pleistocene deposits in Europe. Quatrefages and Hamy used the accepted techniques of craniometry (detailed measurements of the shape of the skull, particularly the cephalic index and the facial angle) to identify several distinct human races that existed in Europe during the Pleistocene. In three papers published between 1873 and 1874, and later expanded upon in their book Crania ethnica (1882) they identified a Canstadt race (represented by the Neanderthal skull from Germany and other similar skulls), a Cro-Magnon race (represented by the skeletons found at Les Eyzies and other sites), and brachycephalic races (represented by fossils found at Furfooz in Belgium and Grenelle in France). In the preface to the book, Quatrefages acknowledged that much of the research for the project had been conducted by Hamy. Hamy also published many papers describing recently discovered human fossils thought to date from the Ice Age. These publications were important not only for the evidence they provided about these early humans but also because he helped to establish the techniques that defined how to examine human fossils. It is also important to recognize that Hamy and Quatrefages focused on identifying prehistoric human “races” rather than discussions of human evolution, since the fossils they examined appeared to be fully human.

Hamy traveled to Copenhagen and Stockholm in 1874 to examine the ethnological and anthropological collections in their renowned museums in order to reorganize the anthropological collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. He continued to investigate the prehistoric archaeology and anthropology of France and beginning in 1877 he participated in the work of the Commission de la Topographie des Gaules and the Commission de Géographie de l’Ancienne France. Hamy collaborated with archaeologist Alexandre Bertrand, director of the Musée d’Archéologie Nationale (Museum of National Archaeology), on an installation for the 1878 Exposition Universelle held in Paris. Their exhibit displayed artifacts from the Stone Age, the pre-Roman Gallic period, the Roman period, and the Frankish period in France.

Hamy also participated in the organization of the Musée Ethnographique des Missions Scientifiques located at the Trocadéro Palace, which was also part of the Exposition Universelle. The museum collected together ethnographic artifacts from cultures around the world that were held in the collections of numerous institutions in Paris. This display of ethnographic objects was intended to stimulate interest in colonial expansion and the success of the exposition led to calls for the creation of a permanent ethnographic museum. Quatrefages supported this idea and the Chambre des Députés (Chamber of Deputies) accepted this proposal. On 19 July 1880 the Minister of National Education, Jules Ferry, signed the decree creating the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. Hamy was appointed curator of the museum and director of scientific missions. The museum contained an impressive collection of ethnographic, prehistoric, and physical anthropology specimens. Hamy’s principles for arranging the collections in the museum were laid out in an influential book, Les Origines du Musée d’Ethnographie (The Origins of the Museum of Ethnography) published in 1890, which reflected the attitude of many scientists of that time that biological and cultural phenomena were linked. Hamy also wanted to reconcile the prevailing views of biological and cultural evolutionism and with the idea of diffusionism. Hamy served as curator of the museum from 1880 until he resigned in 1906 in protest over the dismal state of the museum’s budget and the lack of support for the institution. The museum was reorganized into the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Man) in 1938.

Hamy was becoming increasingly involved in many prominent French anthropological and ethnological institutions. Hamy joined many of the leading French anthropologists, including Quatrefages, Broca, Gabriel de Mortillet, and Paul Topinard in attending the international anthropological congress held in Moscow in 1879. In 1882 Hamy founded and edited the journal Revue d’ethnographie which ceased publication in 1889 when it merged with Matériaux pour l’histoire primitive et naturelle de l’homme (edited by Emile Cartailhac and Ernest Chantre) and with Révue d’Anthropologie (edited by Topinard) to form the new journal L’Anthropologie. Hamy became professor of anthropology at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in 1892, upon Quatrefages’ retirement, and he held this influential position until 1908. During the course of his career, Hamy’s scientific interests gradually changed. For many years he had been interested in the indigenous peoples of the Americas. In 1874 and again in 1887 Hamy conducted research in Mexico where he collected documents and material on Mexican history and archaeology, which led to the publication of Anthropologie du Mexique (1884). This interest led him to establish the Société des Américanistes (Society of Americanists) in 1895, which was devoted to the ethnological and anthropological study of the native people and cultures of the New World. Hamy served as the editor of the Journal de la Société des Américanistes from its inception in 1895 until 1908. Thanks to the financial support of the duc de Loubat, the Paris publisher Ernest Leroux was able to print the Galerie américaine du Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1897 consisting of Hamy’s ethnographic and archaeological publications and 60 plates. Hamy continued to study other parts of the world as well and in 1887 he was part of a scientific mission to Tunisia, along with the explorer John Errington de la Croix, that studied the archaeology and ethnology of the Berbers.

Hamy was a member of many of the leading scientific societies in France. He was a member of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris from 1867 to 1908, serving as its president in 1884 and 1906. He became a member of the Société de Biologie in 1873, of the Société de Géographie in 1876, and of the Société Asiatique in 1890. An interest in folklore led Hamy to become a member of the Société des Traditions Populaires, serving as the Society’s president in 1887 and 1895. Hamy’s connection to medicine led him to become a member of the Académie Nationale de Médecine as well as the Société Française d’Histoire de la Médecine. Hamy was a founding member in 1872 of the Association Française pour l’Avancement des Sciences (French Association for the Advancement of the Sciences) and he served as its president in 1901. He was appointed a member of the prestigious Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1890. He was an active participant in the Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistoriques (International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology) and was president of the 1906 meeting held in Monaco. In addition, he was a member of the Société de l’Histoire de Paris et de l’Île-de-France as well as the Société des Amis des Monuments Parisiens. He was also a corresponding member of the Société d’Anthropologie de Lyon, as well as a corresponding or honorary member of scientific institutions in many other European counties.

The Ministry of Public Instruction appointed Hamy to several committees and commissions. These included the Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques in 1877, where he served as secretary of its Section de Géographie Historique et Descriptive beginning in 1886. In this capacity he was involved in reviving the geographical study of France and he served as the editorial secretary of the Bulletin de Géographie Historique et Descriptive. He also became a member of the Commission des missions scientifiques et littéraires in 1881. Hamy served as a member of the Fondation Garnier, which was created to support the exploration of central Africa and Asia.

Hamy received many honors during his long career. He was made an Officer of the Légion d’honneur in 1889. He was also an Officier de l’Instruction publique; a Commander of the Royal Order of Isabelle la Catholique; a Commander of the Order of Saint-Otaries de Monaco; an Officer of the Order of Léopold; a Knight of the Order of Saint-Maurice-et Lazare; a Knight of the of the Order of Saint-Charles of Monaco; a Knight of the Order of Saint-Stanislas; and Commander of the Etoile Polaire. Ernest-Théodore Hamy died in Paris at the Maison de Buffon, his residence at the Museum of Natural History, on 18 November 1908.

Selected Bibliography

“Sur les silex taillés de Chatillon, près Boulogne.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 6 (1865): 419-423.

“Étude sur l’ancienneté de l’espèce humaine dans le département du Pas-de-Calais.” Bulletin de la Société académique de Boulogne-sur-Mer 1 (1866): 217-248.

Henri-Émile Sauvage and E. T. Hamy, Étude sur les terrains quaternaires du Boulonnais et sur les débris d’industrie humaine qu’ils renferment. Paris: Librairie scientifique, industrielle et agricole, 1866.

“Étude sur le crâne de l’Olmo.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 3 (1868): 112-118.

“Note sur les ossements humains trouvés dans le Tumulus de Genay (Côte-d’Or).” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 4 (1869a): 91-98.

“L’Egypte quaternaire et l’ancienneté de l’homme.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 4 (1869b): 711-719.

Précis de paléontologie humaine. Paris: J.B. Baillière, 1870.

“Note sur les ossements humains fossiles de la seconde caverne d’Engihoul, près Liège.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 6 (1871): 370-386.

“Observations à propos du squelette humain fossile des cavernes de Baoussé-Roussé, dites grottes de Menton.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris ser. 2, 7 (1872): 589-593.

“Quelques observations anatomiques et ethnologiques à propos d’un crâne humain trouvé dans les sables quaternaires de Brux (Bohême).” Revue d’anthropologie 1 (1872): 669-682.

Armand de Quàtrefages and Ernest Théodore Hamy. “Races humaines fossiles – races de Canstadt.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 8 (1873): 518-523.

“Sur quelques ossements découverts dans la troisième caverne de Goyet, près Namèche (Belgique).” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 8 (1873): 425-435.

“Sur les ossements humains de Solutré.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 8 (1873): 842-850.

Armand de Quàtrefages and Ernest Théodore Hamy. “La race de Cro-Magnon dans l’espace et dans le temps.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 260-266.

“Note sur le squelette humain trouvé dans la grotte de Sorde, avec des dents sculptées d’ours et de lion des cavernes.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 525-531.

“Sur le squelette humain de l’abri sous roche de la Madelaine.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 599-606.

“Description d’un squelette humain fossile de Laugerie-Basse.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 652-8.

Armand de Quàtrefages and Ernest Théodore Hamy. “Races humaines fossiles, mésaticéphales et brachycéphales.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 819-826.

Armand de Quàtrefages and Ernest Théodore Hamy. “Races humaines fossiles, Race de Cro- Magnon.” Comptes rendus de l’Académie des sciences Paris 78 (1874): 861-867.

“Note sur le squelette humain trouvé dans la grotte de Sorde, avec des dents sculptées d’ours et de lion des cavernes.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 525-531.

“Sur le squelette humain de l’abri sous roche de la Madelaine.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 599-606.

“Sur les ossements humains du dolmen des Vignettes, à Léry (Eure).” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 606-609.

“Description d’un squelette humain fossile de Laugerie-Basse.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 652-658.

“Détermination ethnique et mensuration des crânes néolithiques de Sordes.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 813-817.

“Fossil Man from La Madelaine and Laugerie Basse.” In E. Lartet, H. Christy (eds), Reliquiae Aquitanicae, Being Contributions to Anthropology and Palaeontology of Périgord and the Adjoining Provinces of Southern France. Pp. 255-272. London: Williams and Morgate, 1875.

“De l’extension géographique des populations primitives en Belgique et dans le nord de la France.” Comptes rendus Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistorique 1877, p. 269-278.

“Note sur une voûte de crâne trouvée dans les alluvions du Petit-Quevilly, près Rouen.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 2 (1879): 482-487.

Armand de Quatrefages and Ernest-Théodore Hamy. Crania ethnica. Les cranes des races humaines, décrits et figurés d’aprés les collections du Muséum d’histoire naturelle de Paris, de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris et les principales collections de la France et de l’étranger. 2 vols. Paris, J.B. Baillière et fils, 1882.

Anthropologie du Mexique. Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1884.

Études ethnographiques et archéologiques sur l’Exposition coloniale et indienne de Londres. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1887.

Les origines du Musée d’ethnographie; histoire et documents. Paris: E. Leroux, 1890.

Études historiques et géographiques. Paris: E. Leroux, 1896.

Decades americanae: mémoires d’archéologie et d’ethnographie américaines. 3 vols. Paris: E. Leroux, 1896-1902.

Galerie américaine du Musée d’ethnographie du Trocadéro; choix de pièces archéologiques et ethnographiques. Paris: E. Leroux, 1897.

Other Sources Cited

Henri de Longuy, “Notice archéologique sur Santenay (Cote-d’Or).” Mémoires de la Société Éduenne 12 (1883): 125-206.

Henri de Longuy and Claude Sauvageot, Notice sur Santenay (Côte d’Or). Étude géologique, paléontologique et archéologique, analyses des eaux. Autun: de Dejussieu père et fils, 1884.

Secondary Sources

José Contel and Jean-Philippe Priotti (eds.), Ernest Hamy, du muséum à l’Amérique: logiques d’une réussite intellectuelle. Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2018.

L. Vallin, “Les pionniers de la Préhistoire régionale: Ernest Hamy (1842-1908).” Numéro spécial Boulonnais. Cahiers de Préhistoire du Nord (1989): 16-19.

Théodore Reinach “Notice sur la vie et les travaux de M. le Dr Hamy.” Comptes-rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 55 (1911): 55-142.

Résumé des Travaux scientifiques de E. -T. Hamy. Paris: Hennuyer. 1887.

Ernest-Théodore Hamy, Mémorial de famille, souvenirs de trois générations (1752-1841). Angers: A. Burdin et Cie, 1905.

Henri Cordier, A la mémoire de Ernest-Théodore Hamy, 22 juin 1842 – 18 novembre 1908. Corbeil: Crété, 1908.

“Théodore-Jules-Ernest Hamy.” L’Anthropologie 19 (1908): 595-603.

“Le Professeur Hamy.” Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 5 (1908): 140-149.

Jean Babelon, “Discours prononcés aux funérailles de M. Ernest Hamy.” Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 5 (1908): 150-154.

Léon Vaillant, “Discours prononcés, au nom du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, aux obsèques de M. le professeur Hamy.” Bulletin du Muséum national d’histoire naturelle 14 (1908): 322-325.

Henri Cordier, “Le Docteur E.-T. Hamy.” Bulletin de géographie historique et descriptive (1908): 165-166.

Paul Sébillot, “E.-T. Hamy.” Revue des traditions populaires 23 (1908): 461.

X. Gillot, [Necrologie]. Bulletin Société d’histoire naturelle d’Autun 23 (1908): 19-26.

Ernest Chantre, “Le Docteur E. Hamy, sa vie et ses travaux (1842-1908).” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Lyon 28 (1909): 13-28.

Émile Houzé, “Ernest-T. Hamy, Note biographique” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Bruxelles 28 (1909): xliii-lv.

Rene Verneau, Le professeur E-T Hamy et ses prédécesseurs au Jardin des Plantes. L’Anthropologie 21 (1910) 257-279.