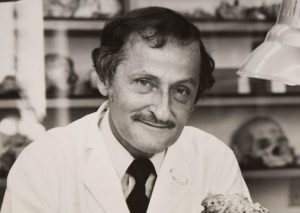

Phillip Tobias (1925-2012)

Matthew Goodrum

Phillip Vallentine Tobias was born in Durban, Natal, Republic of South Africa, on 14 October 1925. His father, Joseph Newman Tobias, was born in Portsmouth, England and emigrated to South Africa where for many years he ran a shop. His mother, Fanny Rosendorff, was a piano teacher who was born in Edenburg, in the Orange Free State in South Africa. Joseph Tobias’s great grandfather was the Anglo-Jewish publisher Isaac Vallentine. Phillip Tobias learned to read at the age of three, but his childhood was disrupted by his parents’ divorce as well as his father’s bankruptcy. When Tobias was fifteen his sister Valerie, then only twenty-one, died of diabetes and this was a major factor that contributed to his decision to study medicine. Tobias attended Durban Preparatory High School from 1933 to 1935 but spent the following year at President Brand School, in Bloemfontein, and the next two years at St Andrews School in Bloemfontein. He entered Durban High School in 1939 and graduated in 1942. During those years he frequently visited the Durban Natural History Museum where he was fascinated by the exhibits on genetics, zoology, and archaeology.

In 1944 Tobias enrolled in the medical school of the University of the Witwatersrand, where he was appointed Demonstrator in Histology and Instructor in Physiology in 1945. While at the university Tobias studied with the anatomist Raymond Dart and the histologist Joseph Gillman. Tobias was introduced to paleoanthropology through Dart, who described the first Australopithecus africanus fossil, and under Gillman’s influence Tobias began researching chromosomes. Tobias also became involved in student politics at a time when national politics was affecting university education. He was elected president of the National Union of South African Students three times (1948-50) and in this role he led some of the earliest campaigns against the apartheid government. In 1948 the National Party came to power in South Africa and one consequence of its apartheid policies was that the student union, which had previously been non-racial, was now racially segregated. Tobias’ opposition to this policy marks the beginning of a life-long effort to combat apartheid.

Tobias acquired some of his first experiences with archaeology and paleontology at this time. In 1945 he led a group of fellow students to Sterkfontein, where Robert Broom had discovered australopithecine fossils in the 1930s. That same year, at the suggestion of South African archaeologist Clarence Van Riet Lowe, Tobias led another student expedition to the Makapansgat Valley where he found fossil baboon skulls among the breccia from Limeworks Cave, which indicated that its deposits were contemporaneous with australopithecine deposits at other sites. Tobias also visited Mwulu’s Cave for the first time in 1945, where he found a Paleolithic stone tool. Tobias then organized excavations in Mwulu’s Cave in 1947 that recovered Middle Stone Age artifacts (Tobias 1949; 1954). Tobias received a B.Sc. degree in Histology and Physiology in 1946 and a B.Sc. Honors (1st Class) in Histology in 1947, and he completed his medical degree (M.B., B.Ch.) in 1950. He was appointed a lecturer in anatomy at the University of the Witwatersrand in 1951 and in 1953 he received his Ph.D., under the supervision of Joseph Gillman, for a thesis titled Chromosomes, Sex-Cells, and Evolution in the Gerbil. This was published in London a few years later (Tobias 1956). Tobias was later awarded a D.Sc. degree in 1967 for his work on the Zinjanthropus fossil.

Tobias undertook postgraduate research in physical anthropology in 1955 with Jack Trevor in the Duckworth Laboratory at Cambridge University, in England, where he was a Nuffield Dominion Senior Traveling Fellow. While examining hominid fossils housed in the British Museum, he decided to conduct a new investigation of the Kanam mandible that was first discovered by Louis Leakey at Olduvai Gorge in 1932 (Tobias 1960). The following year he traveled to the United States to continue his postgraduate studies as a Rockefeller Traveling Fellow in anthropology, human genetics, and dental anatomy and growth. At the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor he did work in anatomy with Bradley Patten, in human genetics with James Neel, and in anthropology with Fred Thieme and James Spuhler, and at the University of Chicago he worked with Sherwood Washburn and was exposed to the ideas of the New Physical Anthropology. After returning to South Africa, Tobias was the chairman of a committee in 1958 that successfully promoted the creation of the Institute for the Study of Man in Africa. The institute, established to honor the work of Raymond Dart, opened at the University of the Witwatersrand with the objective of studying African peoples as well as the evolution of humans in Africa (see Tobias 1958). In 1959 Tobias succeeded Raymond Dart as professor and Head of the Department of Anatomy and Human Biology at the University of the Witwatersrand. He held this position until 1990 and in 1993 he was appointed professor emeritus. In addition to being professor of anatomy he served as Dean of Medicine at the university from 1980 to 1982 and also served as a member of the Senate and Council of the University. Among his many official positions, Tobias was appointed Honorary Professor of Palaeoanthropology at the Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research in 1977 and Honorary Professor in Zoology in 1981.

During the course of his career, Tobias was involved in numerous archaeological and paleontological excavations, he conducted research into the physical anthropology of African peoples, and he contributed significantly to paleoanthropology. With Raymond Dart’s encouragement, he joined the French Panhard-Capricorn Expedition in 1951, where he collected anthropometric data on the San people of the Kalahari Desert. He also discovered many new archaeological sites in what was then the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana). Tobias was invited by Desmond Clark, of the Rhodes-Livingstone Museum, and Henry A. Fosbrooke, of the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, to participate in an expedition during 1957 and 1958 to study the Gwembe Tonga people of Zambia. Over the following decades he continued to investigate and write about the Kalahari San (Bushmen) and other African peoples. Much of this research focused on the anatomy, growth, physique and secular trends in southern African peoples. Tobias created and chaired the Kalahari Research Committee, which conducted annual multidisciplinary scientific studies of the San of the Kalahari between 1956 and 1971. This research resulted in the publication of a monograph edited by Tobias titled The Bushmen (1978).

The scientific discipline of physical anthropology was undergoing significant change at this time. Tobias disagreed with many of the ideas promoted by earlier generations of physical anthropologists regarding Africans. Rather than seeking to identify and characterize the distinct “races” present on the continent, Tobias argued for the essential biological unity among African peoples. He rejected the idea that racial classification had any biological meaning. Instead, he argued that genetic variation among African populations should be explained by environmental and evolutionary factors. He also rejected the widely held notion of a “Bantu race” and suggested the idea of a “Southern African Negro” as a more appropriate anthropological term. His physical anthropology research also led Tobias to write about the concept of race and the implications of racism in the modern world. He delivered a lecture in 1961 titled The Meaning of Race to the Union of Jewish Woman in Johannesburg, which was published in 1961 and subsequently greatly expanded in a second edition that appeared in 1972. This book critiqued the purported scientific basis for the white supremacist belief in racial purity and rejected South African apartheid racism and Afrikaner nationalist ideology. He argued for a genetic model of population variation that contrasted with the racial typology and racial classification schemes that dominated early twentieth century physical anthropology.

Tobias devoted much of his career to groundbreaking research in paleoanthropology. He analyzed and described hominid fossils from such geographically diverse places as Ubeidiya in Israel, Chemeron in Kenya, and from Haua Fteah in Libya. But he is best-known for his work on hominid fossils from Olduvai Gorge, in Tanzania, and from various sites in South Africa. In 1959, Tobias presented a paper at the fourth Pan African Congress of Prehistory, held in Leopoldville (now Kinshasha), on the controversial Kanam mandible found by Louis Leakey in 1932. This was the same meeting where Louis and Mary Leakey announced their recent discovery of the skull of a new hominid (OH 5) at Olduvai Gorge. They were impressed enough by Tobias’ paper that they invited him to undertake the analysis and description of this fossil, since neither Louis nor Mary were trained anatomists. Tobias made detailed measurements of the cranium, attributed to the new species Zinjanthropus boisei, and compared it with various Australopithecus specimens as well as to other hominid species. His comprehensive analysis of the fossil, published in Olduvai Gorge, Vol. 2: The Cranium and Maxillary Dentition of Australopithecus (Zinjanthropus) boisei (1967), garnered wide praise and served as a model for how hominid fossils should be studied. Significantly, he concluded his discussion by arguing that all the existing australopithecine fossils, which at this time were still classified under several different genera, should instead be placed under the single genus Australopithecus containing three species (A. africanus, A. robustus, and A. boisei).

Soon after the discovery of the Zinjanthropus specimen at Olduvai Gorge, the Leakey team unearthed new fossils belonging to a quite different hominid. In 1960 the Leakey’s excavated a partial juvenile cranium, a mandible, two clavicles, and hand bones (OH 7) along with a fossilized foot (OH 8). Then in October 1963 a mandible and fragments of a cranium (OH 13) were discovered. Tobias worked with Louis Leakey and British primatologist John Napier to examine this collection of new fossils. After careful study and some deliberation Leakey, Napier, and Tobias argued that since the specimen’s cranial capacity was larger than in australopithecines and given the evidence for a precision grip in the hand bones, which indicated this hominid possessed the ability to use tools, they felt justified in classifying these fossils as a new species, Homo habilis, which they considered to be a transitional species between Australopithecus africanus and Homo erectus. When they announced this new species in the journal Nature (Leakey, Tobias, and Napier 1964), they ignited a debate within the anthropology community over the creation and characterization of this new species that has continued ever since. Over the next several years, Tobias published a series of papers on the Olduvai Gorge hominid fossils (Tobias 1965a; 1965b; 1965c; 1966). Tobias also collaboration with German geologist Ralph von Koenigswald to examine the fossil hominids from Java and compare them with the Oludvai Gorge hominids, which resulted in a seminal paper (Tobias and von Koenigswald 1964). Excavations at Olduvai Gorge produced additional fossils attributed to Homo habilis (OH 16, OH 24) and Louis Leakey once again asked Tobias to conduct the analysis and description of these fossils. Tobias’ description of all the Olduvai Homo habilis fossils was published as Olduvai Gorge, Vols. 4A and 4B. The Skulls, Endocasts and Teeth of Homo habilis in 1991. In the conclusion of this volume, Tobias continued to support the view that there was adequate morphological space between Australopithecus africanus and Homo erectus to accommodate Homo habilis.

For much of his career Tobias was closely associated with renewed excavations conducted at Sterkfontein, a site where South African paleontologist Robert Broom first found Australopithecus fossils in 1936. Tobias directed a new research program at Sterkfontein from 1966 to 1993, working initially with Alun Hughes, who supervised field excavations until the early 1990s, and later with Ronald Clarke. This research focused on cave and site formation, stratigraphy, dating, faunal analysis, taphonomy, palaeoecology, hominid evolution and cultural evolution. In 1977, Tobias established the Palaeoanthropology Research Programme (within the Department of Anatomy). It was renamed the Sterkfontein Research Unit in 1979 and it has become internationally famous as a center for paleoanthropological research. In the course of the last half century, work at Sterkfontein has led to the recovery of approximately six hundred hominid fossils, most belonging to Australopithecus africanus. However, these also include a cranium (Stw 53) with Homo features discovered at Sterkfontein in August 1976 among stone tools and a fauna indicating an age of 2.0-1.5 million years (Hughes and Tobias (1977).

In 1995 Tobias and his colleague Ronald Clarke announced one of the most important discoveries made at Sterkfontein, a nearly complete skeleton of a 3.67 million year old australopithecine that was given the nickname Little Foot (Stw 573). The bones had originally been blasted out of the ground by lime miners in 1980 from the Silberberg Grotto at Sterkfontein and a field worker mistakenly stored them with some fossil animal bones. Thus, they remained unstudied until 1994 when Clarke recognized them as foot bones belonging to a hominid. In 1997, Clarke discovered more leg and foot bones in a box of fossils, which he realized also belonged to Stw 573. Clarke guessed that the rest of the skeleton could still be in the cave deposits. Clarke’s technical assistants, Stephen Motsumi and Nkwane Molefe, initiated new excavations at the Silberberg Grotto and soon found more bones and over the next fifteen years most of the skeleton was recovered. In early papers describing the foot bones, Tobias and Clarke (Clarke and Tobias 1995; Tobias and Clarke 1996) noted that although the bones showed adaptation to bipedalism, the big toe could extend sideways from the rest of the foot. From this they argued that Little Foot spent much of its time in trees, using its splayed feet to grasp branches, but when it came to the ground this hominid would have walked erect. This conclusion reignited the controversy among paleoanthropologists over the evolution of bipedalism.

In the course of his examination of African hominid fossils, Tobias became interested in the evolution of the human brain and the origins of spoken language. He developed a method to estimate the endocranial volume of the OH 7 Homo habilis cranium (Tobias 1964) and the detailed endocasts made by American anthropologist Ralph Holloway prompted Tobias’ interest in the relationship between endocranial morphology and spoken language. Tobias devoted many years to studying the endocasts of early hominids, especially A. africanus, A. boisei and H. habilis. In 1969 Tobias delivered the James Arthur Lecture at the American Museum of Natural History and this was subsequently published as a book, The Brain in Hominid Evolution (1971). In this work, Tobias discussed the evolution of the brain in hominids from his studies of endocranial casts of australopithecine, Homo habilis, Homo erectus, and Homo sapiens fossils. He observed that the hominid brain expanded in size steadily and fairly regularly from 2 million years ago to about 40,000 years ago. Furthermore, Tobias argued that tool-making was one of the major factors that drove the increase in brain volume and complexity in hominids, and that cultural behaviors such as tool-making, organized hunting, and speech were all interrelated.

In 1973 Tobias demonstrated for the first time the presence of prominences in the localities of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, regions of the brain involved in speech in modern humans, in the endocasts of Homo habilis, suggesting that this species might have been capable of speech. He published several innovative papers examining questions around brain evolution in hominids and its relationship to stone tool culture and the emergence of language (Tobias 1975a; 1979; 1983b; 1987). Tobias also published an influential article in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in 1970 titled “Brain-Size, Grey Matter and Race—Fact or Fiction?” that was inspired by his long-standing critique of racism. In this paper he denounced the old and persistent idea that there is a link between brain-size, race, and intelligence. Tobias was also involved in one of the first attempts to use computed tomography to image the endocranial cavity of hominid fossils (Tobias 2001). In another of his books, titled Man, the Tottering Biped (1982), Tobias discussed the evolution of bipedalism in hominids. He describes the changes that were required to the bones and muscles of the spinal column, pelvis, and legs to achieve bipedalism. He noted that changes to the nervous system were necessary as well, in order to maintain balance. This included an increase in the size of the cerebellum in hominid brains, which is a region of the brain that is important for balance.

During his career, Tobias did much to promote the science of anatomy in South Africa. He collaborated with University of the Witwatersrand anatomist Maurice (Toby) Arnold to write a three-volume anatomy textbook, Man’s Anatomy (1963-64), that subsequently went through several editions. This text was influential in part because it introduced new methods of teaching anatomy. In addition, Tobias was one of the founders, in 1968, of the Anatomical Society of Southern Africa. The impetus for creating an anatomical society grew out of an Anatomy Colloqia series that Tobias initiated in 1964 with the purpose of bringing together anatomists from across South Africa. For many years Tobias served as the president of the Anatomical Society of Southern Africa. During his tenure as professor of anatomy, Tobias worked to build up the collections of the Hunterian Museum of Anatomy, which is housed in the School of Anatomical Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, and he contributed to making it an excellent teaching and research facility.

It is impossible to review the career of Phillip Tobias without discussing the social and political context of the government policy of apartheid in the Republic of South Africa that affected so much of his professional life. Beginning when he was a student and continuing into his years as a prominent researcher and professor, Tobias was an outspoken critic of apartheid. Tobias noted on the occasion of his acceptance of the Walter Sisulu Special Contribution Award in 2007 that: “Only a few years after I arrived here [at the University of the Witwatersrand], the Apartheid regime came to power under D. F. Malan and they won that fateful election on an Apartheid platform. Every branch of society was to be segregated. Discrimination was to be enforced between the haves and the have-nots, between black and white South Africans.” Tobias opposed this policy in a variety of ways. He was a member of the executive committee of the Education League of South Africa, a body established to campaign against apartheid education, from its creation in 1948 to 1958. In his role as a South African academic Tobias publicly opposed apartheid, even though there were real risks to his career. South African authorities even warned him periodically that his research grants might be withdrawn if he failed to follow the government’s official policies. Yet, despite invitations to join the faculty of universities outside South Africa, Tobias chose to remain at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Following the death in prison of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko in 1977, Tobias and other South African academics presented a formal complaint to the South African Medical and Dental Council concerning the treatment of Biko by the police. They wanted the council to identify and censure the doctors who were likely complicit in Biko’s death. When the council failed to act, Tobias and other activists took the council to the Supreme Court over the matter. For a number of years there was an international academic boycott of South African academics because of apartheid and it hindered the advancement of South African science. Members of the South African scientific community were not permitted to publish in some journals and were even refused attendance at certain conferences. However, Tobias criticized the academic boycott of South Africa by the executive committee of the British national organizing committee of the World Archaeological Congress, which was held in Southampton in 1986. He argued that “isolating South African scholars would only result in our universities running down and down — and I couldn’t bear the thought of bequeathing a series of run-down universities to our post-apartheid successors.” Tobias also used his expertise in physical anthropology and paleoanthropology to critique racist political policies and the social and scientific ideas about race that these policies drew upon. He saw the archaeological and paleontological evidence for the origins of humanity in Africa as a significant political fact and he thought it was the scientist’s duty to expose the truths about race as a way to counter the assumptions of apartheid.

Besides being a prolific scientist, Tobias pursued a variety of other interests. In 2002 he hosted a television series for the South African Broadcasting Corporation called Tobias’ Bodies, which consisted of six episodes that explored issues relating to genetics, anatomy and primatology. Toward the end of his career Tobias wrote about the history of paleoanthropology, focusing especially on the contributions of South African scientists and discoveries. His book on the career of Raymond Dart, Dart, Taung, and the “Missing Link” (1984), written for the occasion of Dart’s 90th birthday, remains one of the best treatments of his mentor’s life and paleoanthropological research. After the end of apartheid, Tobias led negotiations to have the remains of Saartjie (Sarah) Baartman, a Khoi woman displayed throughout Europe in the nineteenth century and known as the Hottentot Venus, to be repatriated from Paris. Her grave is now a national heritage site. Tobias also led the successful campaign for the Sterkfontein caves, known as the Cradle of Humankind, to be proclaimed a UNESCO World Heritage site, because of the importance of the site to our understanding of human evolution.

Tobias held a number of academic posts throughout his career. In addition to being Professor of Anatomy and Human Biology at the University of the Witwatersrand, he was also Honorary Professorial Research Associate and Director of the Sterkfontein Research Unit, as well as Andrew Dickson White Professor-at-Large at Cornell University (USA). He was a visiting professor at a number of institutions including the University of Pennsylvania (USA), the University of KwaZulu-Nalal, and Cambridge University (England). He organized two very successful international conferences at the University of the Witwatersrand. The first was the Taung Diamond Jubilee in 1985, celebrating Raymond Dart’s discovery of the Taung Australopithecus fossil. The second was the Dual Congress of the International Association of Human Biologists and the International Association of Human Palaeontology held in 1998.

Tobias received seventeen honorary degrees from around the world and was elected a fellow, associate, or honorary member of over twenty-eight learned societies. He became a member of the Royal Society of South Africa in 1960, a member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in 1978, and a member of the Academy of Science of South Africa in 1996. In Britain he was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1992 and a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1996. In addition, he was a Foreign Associate of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), the American Philosophical Society, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Tobias served on the terminology committee of the International Federation of Anatomical Associations, and he also served as the first chairman of the South African National Commission for UNESCO.

Tobias received dozens of awards in recognition of his scientific achievements. Among the more prominent are the Simon Biesheuvel Medal granted by the South African Association for the Advancement of Science (1966), the Rivers Memorial Medal granted by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (1978), the Balzan Prize granted by the International Balzan Foundation (1987), the John F.W. Herschel Medal granted by the Royal Society of South Africa (1989), the L. S. B. Leakey Prize (1991), the Huxley Memorial Medal granted by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (1996), the Charles R. Darwin Lifetime Achievement Award granted by the American Association of Physical Anthropologists (1997), and the Wood Jones Medal granted by the Royal College of Surgeons (1997). The Royal Society of South Africa confers very few honors and so it is a mark of his achievements that Tobias was only one of two South African Honorary Fellows of the Society and one of only a few recipients of the Society’s highest medal, the John Herschel Medal. He also received honorary degrees from nearly two dozen universities around the world and was nominated three times for a Nobel Prize.

Besides these scientific awards, Tobias also received numerous civil honors. These include South Africa’s Order for Meritorious Service (Gold Class) (1992), Commander of the National Order of Merit of France (1998), Commander of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Italy (2000), the Honorary Cross for Science and Arts (first class) bestowed by the government of Austria (2002), Commander of the Order of St. John (2003), and the Walter Sisulu Special Contribution Award (2007). President Nelson Mandela awarded him the rarely given Order of the Southern Cross (class II) in 1999. Tobias was active in many professional organizations and in addition to being one of the founders of the Anatomical Society of Southern Africa in 1968, he was also a founding member of the International Association of Human Biologists in 1967 as well as a founding member of the South African Society for Quaternary Research in 1969. He was one of the founders of the International Society of Cryptozoology in 1981 and was the founder and chairperson of Medical Education for South African Blacks (MESAB) in 1986.

Tobias never married and had no children, but he left a lasting legacy among his students and colleagues at the University of the Witwatersrand. He was a prodigious scholar who published more than 1300 articles and authored or co-authored numerous books, including a memoir of his early life titled Into the Past (2005). Tobias himself was the subject of several Festschriften honoring his career, including From Apes to Angels: Essays in Anthropology in Honor of Phillip V. Tobias (1990) published on the occasion of his 65th birthday and his retirement as Chair of Anatomy and Human Biology, as well as Images of Humanity: Selected Writings of Phillip V. Tobias (1991). He was the subject of a documentary film made by Seth Asch in 1991 titled Time, Transience and Tobias and in 1975 he was featured in the documentary film Tobias on the Evolution of Man produced by the National Geographic Society. Tobias died on 7 June 2012 in Johannesburg at Wits University Donald Gordon Medical Centre. He was buried at the West Park Jewish Cemetery in Johannesburg on the 10th of June 2012.

Selected Bibliography

“The Excavation of Mwulu’s Cave, Potgietersrust District.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 4 (1949): 2-13.

“Climatic Fluctuations in the Middle Stone Age of South Africa, as Revealed in Mwulu’s Cave.” Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 34 (1954): 325-334.

Chromosomes, Sex-cells and Evolution in a Mammal. London: Percy Lund, Humphries, 1956.

“The Kanam Jaw.” Nature 185 (1960): 946–947.

The Meaning of Race. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations, 1961 (2nd edition, 1972).

“New Evidence and New Views on the Evolution of Man in Africa.” South African Journal of Science 57 (1961): 25-38.

“Cranial Capacity of Zinjanthropus and Other Australopithecines.” Nature 197 (1963): 743-746.

“The Olduvai Bed I Hominine with Special Reference to Its Cranial Capacity.” Nature 202 (1964): 3-4.

Louis Leakey, Phillip Tobias, and John Napier, “A New Species of The Genus Homo from Olduvai Gorge.” Nature 202 (1964): 7-9.

Phillip Tobias and G. H. R. von Koenigswald, “A Comparison Between the Olduvai Hominines and Those of Java and Some Implications for Hominid Phylogeny.” Nature 204 (1964): 515-518.

“Early Man in East Africa.” Science 149 (1965a): 22-33.

“New Discoveries in Tanganyika: Their Bearing on Hominid Evolution.” Current Anthropology 6 (1965b): 391-411.

“Australopithecus, Homo habilis, Tool-Using and Tool-Making.” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 20 (1965c): 167-192.

“The Distinctiveness of Homo habilis.” Nature 209 (1966): 953-957.

Olduvai Gorge, Vol. 2: The Cranium and Maxillary Dentition of Australopithecus (Zinjanthropus) boisei. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967.

“General Questions Arising from Some Lower and Middle Pleistocene Hominids of the Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.” South African Journal of Science 63 (1967): 41-48.

“Cultural Hominization among the Earliest African Pleistocene Hominids.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 33 (1968): 367-376.

“Brain-Size, Grey Matter and Race—Fact or Fiction?” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 32 (1970): 3-25.

“Human Skeletal Remains from the Cave of Hearths, Makapansgat, Northern Transvaal.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 34 (1971): 335-367.

The Brain in Hominid Evolution. New York: Columbia University Press, 1971.

“Implications of the New Age Estimates of the Early South African Hominids.” Nature 246 (1973): 79-83.

“Brain Evolution in the Hominoidea.” In R.H. Tuttle (ed.), Primate Functional Morphology and Evolution, Mouton. Pp. 353-392. The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1975a.

“Fifteen Years of Study on the Kalahari Bushmen or San: A Brief History of the Kalahari Research Committee.” South African Journal of Science 71 (1975b): 74-78.

Alun Hughes and Phillip Tobias, “A Fossil Skull Probably of the Genus Homo from Sterkfontein, Transvaal.” Nature 265 (1977): 310-312.

“The Earliest Transvaal Members of the Genus Homo with Another Look at Some Problems of Hominid Taxonomy and Systematics. Zeitschrift fur Morphologie und Anthropologie 69 (1978): 225-265.

The Bushmen: Sun Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa. (Edited by Phillip Tobias). Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 1978.

“Men, Minds and Hands: Cultural Awakenings over Two Million Years of Humanity.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 34 (1979): 85-92.

“The Emergence of Man in Africa and Beyond.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B 292 (1981): 43-56.

Man, the Tottering Biped: The Evolution of his Posture, Poise and Skill. Sydney, Australia: Committee in Postgraduate Medical Education, The University of New South Wales, 1982.

“Hominid Evolution in Africa.” Canadian Journal of Anthropology 3 (1983a): 163-190.

“Recent Advances in the Evolution of the Hominids with Especial Reference to Brain and Speech.” Pontifical Academy of Sciences Scripta Varia 50 (1983b): 85-140.

Dart, Taung and the ‘Missing Link’. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press for the Institute for the Study of Mankind in Africa, 1984.

“The Brain of Homo habilis: A New Level of Organization in Cerebral Evolution. Journal of Human Evolution 16 (1987): 741-761.

Phillip Tobias and Maurice Arnold, Man’s Anatomy. 3 vols. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1963-64 (2nd edition 1974; 3rd edition 1977; 4th edition 1988).

Olduvai Gorge, Vols. 4A and 4B. The Skulls, Endocasts and Teeth of Homo habilis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Images of Humanity: Selected Writings of Phillip V. Tobias. Johannesburg: Ashanti Publishing, 1991.

“The Environmental Background of Hominid Emergence and the Appearance of the Genus Homo.” Human Evolution 6 (1991): 129-142.

“The Bearing of Fossils and Mitochondrial DNA on the Evolution of Modern Humans, with a Critique of the ‘Mitochondrial Eve’ Hypothesis.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 50 (1995): 155-167.

Ronald Clarke and Phillip Tobias, “Sterkfontein Member 2 Foot Bones of the Oldest South African Hominid.” Science 269 (1995): 521-524.

Phillip. Tobias and Ronald Clarke, “Faunal Evidence and Sterkfontein Member 2 Foot Bones of Early Hominid.” Science 271 (1996): 1301-1302.

Charles Lockwood and Phillip Tobias, “A Large Male Hominin Cranium from Sterkfontein, South Africa, and the Status of Australopithecus africanus.” Journal of Human Evolution 36 (1999): 637-685.

“Re-creating Ancient Hominid Virtual Endocasts by CT-Scanning.” Clinical Anatomy 14 (2001): 134-141.

Into the Past. A Memoir. Johannesburg, Picador Africa and University of the Witwatersrand Press, 2005.

Darren Curnoe and Phillip Tobias, “Description, New Reconstruction, Comparative Anatomy, and Classification of the Sterkfontein Stw 53 Cranium, with Discussions about the Taxonomy of Other Southern African Early Homo Remains.” Journal of Human Evolution 50 (2006): 36-77.

Evolution of the Anthropological Sciences – Anthropological concepts on primate and human brain development and evolution. Bucuresti: Editura Hasefer, 2007.

Secondary Sources

Bernard Wood, “An Interview with Phillip Tobias.” Current Anthropology 30 (1989): 215-224.

Phillip V Tobias interviewed by Virginia Morell, The Leakey Foundation Oral History Project: Phillip Tobias. Berkeley, California: Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, 2003.

https://ohc-search.lib.berkeley.edu/catalog/MASTER_1989.

“Archaeological Johannesburg: Phillip Vallentine Tobias.” In Mike Alfred, Johannesburg Portraits: From Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo. Pp. 56-66. Cape Town: Jacana Media, 2003.

-

Clark Howell, “Phillip Vallentine Tobias: An Appreciation.” Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 60 (2005): 151–152.

Phillip Tobias, Goran Štrkalj, and Jane Dugard, Tobias in Conversation: Genes, Fossils, and Anthropology. Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press, 2008.

Ronald Clarke and Beverley Kramer, “Phillip Vallentine Tobias Hon. FRSSAf, 1925–2012.” Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 67 (2012): 169-173.

Brunetto Chiarelli, “Phillip Tobias: Born 14 October 1925, Died 7 June 2012, Aged 86.” Human Evolution 27 (2012): 295-298.

Frederick Grine and Peter Ungar, “Phillip Vallentine Tobias: October 14, 1925-June 7, 2012.” Evolutionary Anthropology 21 (2012): 127-129.

Trefor Jenkins, “In Memoriam: Phillip Valentine Tobias 1925-2012.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 67 (2012): 273-274.

Tim White, “Phillip V. Tobias (1925-2012).” Science 337 (2012): 423.

Bernard Wood, “Phillip Vallentine Tobias (1925–2012)”. Journal of Anatomy 222 (2013): 571-572.

Alan Morris, “Phillip Valentine Tobias (1925–2012).” American Anthropologist 115 (2013): 539-541.

Goran Štrkalj and Nalini Pather, “Phillip V. Tobias as an Anatomist.” Clinical Anatomy 26 (2013): 423–429.

Alan Mann, “Phillip Valentine Tobias 1925-2012: A Personal Reminiscence.” PaleoAnthropology (2014): 607-611.

Raymond Corbey, “Homo habilis’s Humanness: Phillip Tobias as a Philosopher.” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 34 (2012): 103-116.