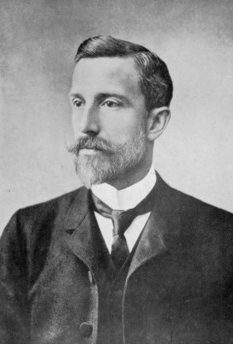

Julien Fraipont (1857-1910)

Matthew Goodrum

Julien-Jean-Joseph Fraipont was born in Liège, Belgium, on 17 August 1857. His father Joseph Fraipont was the director of the Crédit Général Liégeois bank, and his mother was Julienne Collin. Fraipont attended the Collège des Jésuites [Jesuit College] in Liège and among his boyhood friends were Maximin Lohest and Charles Mathien. They were all interested in science and were attracted to Charles Darwin’s recently proposed theory of evolution and its implications for the origin of humans. Their interest in evolution was influenced by the lectures of their teacher, Father Victor van Tricht, who discussed Darwin’s ideas. Fraipont began working in the bank where his father was director, but his desire to pursue a career in science led him to leave his job at the bank and enter the University of Liège in 1875. He attended the classes of the zoologist Edouard van Beneden, who was soon impressed with his young student. As a result, Fraipont first became a préparateur (student demonstrator) in van Beneden’s biological laboratory at the university in 1878, and then in 1881 he was elevated to the position of assistant in the laboratory. Initially Fraipont’s studies were in zoology, and he published several papers with van Beneden on marine organisms. Arrangements were also made for him to spend time at several important marine biological laboratories. He traveled first to Ostend, on the Belgian coast, in 1876 followed by a stay at the biological station at Roskoff on the northern coast of Brittany, in France. He then visited the Zoological Institute at Kiel, in Germany, in 1880 and finally the Zoological Station in Naples, Italy, during 1881 and 1882. These experiences allowed Fraipont to publish a number of papers and monographs on the anatomy and embryology of marine invertebrates, protozoa, hydrozoans, trematodes, and cestodes.

Fraipont’s studies soon expanded beyond just marine zoology. From 1880 to 1884, he worked in both van Beneden’s laboratory of biology and the laboratory of geology led by Gustave Dewalque. Dewalque gave Fraipont the responsibility of teaching the course in paleontology in 1884, and Fraipont took over the course on zoological geography and comparative zoology in 1886. He now became increasingly involved in paleontological research, and his work on Devonian crinoids (Fraipont 1883; 1884) was awarded a prize by the Société géologique de Belgique in 1884. It was at this time that Laurent-Guillaume de Koninck, a paleontologist and professor of chemistry at the university, asked Fraipont to collaborate on his monograph on the Carboniferous bivalves of Belgium (Koninck 1885). His early scientific research was divided between zoology and paleontology. He published papers on the taxonomy and morphology of different groups of animals, including Archiannelids. Fraipont also published several papers on Palaeozoic fossils, the most remarkable being his work on the beautifully preserved echinoderms and fish from the black marble of Dinant. Near the end of his career, he also published a monograph on the Okapia, an unusual animal discovered in the Belgian Congo around 1900. Fraipont concluded that the animal represented a form intermediate between the Cenozoic Giraffidae and present-day giraffes (Fraipont 1907).

In recognition of his scientific accomplishments, the University of Liège appointed Fraipont extraordinary professor in 1886, and in 1889 he was promoted to full professor. In 1891 he took charge of the course on paleontology at a time when he was becoming increasingly interested in Quaternary paleontology and human prehistory. In 1885 Gustave Dewalque directed Fraipont and Pierre Destinez, a préparateur working in geology under Dewalque, to conduct excavations in the Engis caves, where the Belgian physician Philippe-Charles Schmerling found human fossils and stone artifacts in the 1830s. Following this Fraipont joined his childhood friend Maximin Lohest and Ivan Braconier in excavating the Trou al’ Wesse cave at Petit-Modave. Between 1885 and 1887 they unearthed six archaeological layers in the cave containing Pleistocene animal fossils and flint artifacts. Additional excavations there by Fraipont yielded a collective Neolithic burial. Fraipont also collaborated with Ferdinand Tihon, a physician in the town of Theux, near Liège, who was also an avid archaeologist. During their excavations of the Grotte du Docteur, at Huccorgne, from 1886 to 1888 Fraipont and Tihon found Neolithic, Magdalenian, and Mousterian layers containing thousands of stone tools and many animal fossils. Fraipont and Tihon also excavated the Cavernes de la Mehaigne during 1887 and 1888 where they discovered a layer containing Mousterian artifacts with Rhinoceros bones below a layer containing Magdalenian bone tools (Fraipont and Tihon 1889). In 1896 they excavated the Sandron rock shelter at Huccorgne where they unearthed Acheulean and Mousterian artifacts along with a Neolithic ossuary. At the Grotte du Tunnel, they discovered Neolithic pottery and artifacts along with human bones, and in the Grotte de l’Hermitage Fraipont and Tihon unearthed Neolithic burials. Fraipont also excavated the Grotte du Mont Falhise (Anthée) in 1896 where he found broken human bones and Neolithic artifacts (Fraipont 1897). Fraipont compiled the results of his investigations of Neolithic sites in the area around Liège to publish a book titled Les Néolithiques de la Meuse (1900), where he discussed the peoples who lived along the Meuse valley during the Neolithic period.

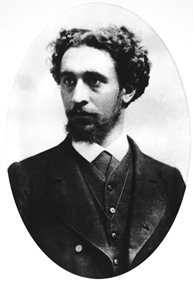

But Fraipont’s most important contribution to paleoanthropology arose from his work on the Neanderthal fossils found in the Grotte de Spy. Marcel de Puydt and Maximin Lohest began their excavations of the cave at Spy in August 1885. Marcel de Puydt had studied law and political and administrative sciences at the University of Liège and was director of the Legal Department of the city of Liège. He was also an avid archaeologist and a member of the Institut archéologique liégeois [Liège Archaeological Institute] and in 1881 he discovered the Neolithic station of Sainte-Gertrude, near Rijckholt. Maximin Lohest studied engineering at the University of Liège and had been appointed the assistant to Gustave Dewalque in 1884. De Puydt first met Lohest and Fraipont in 1881, and they all shared an interest in human prehistory and human origins. De Puydt had known of the cave at Spy since his youth and had explored it somewhat before he and Lohest began their work there. They hired Armand Orban, a former miner from Hoccorgne, to conduct the excavations of the terrace in front of the cave and soon they unearthed numerous Mousterian flint artifacts and Pleistocene animal fossils. These included bones of the wooly rhinoceros, mammoth, cave bear, hyena, and horse. Then in June 1886 the excavations uncovered two human skeletons in the lowest strata of the cave deposits.

Lohest and de Puydt invited Fraipont to conduct the anatomical and anthropological examination of the human fossils despite his lack of experience in anthropology. Fraipont consulted studies of previously discovered Paleolithic human skeletons conducted by Paul Broca, Armand de Quatrefages, Ernest-Théodore Hamy, Rudolf Virchow, Hermann Schaffhaussen, and others. After comparing the two skeletons, and especially the skulls, found at Spy with the Neanderthal fossils found in Germany in 1856 and with other Paleolithic skulls that Quatrefages and Hamy thought belonged to a “Neanderthal race” Fraipont concluded that the Spy skeletons also represented Neanderthals. Since few Neanderthal fossils were known at that time, and there was still a great deal of uncertainty about the Neanderthals, Fraipont’s study of the Spy skeletons helped to clarify some questions regarding the geological age and the anatomy of these early hominids. He argued that the Neanderthals were the earliest known inhabitants of Belgium and that they were the makers of Mousterian tools. Fraipont published several major papers on the Spy skeletons (Fraipont and Lohest 1886; Fraipont 1888; 1891) and later returned to the question of the “Neanderthal race” (Fraipont 1895). Fraipont was awarded the Broca Medal by the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris [Anthropology Society of Paris] in 1888 for the 1886 paper on the Spy skeletons. He also published a book, Les cavernes et leurs habitants [Caves and Their Inhabitants] (1896), where he addressed the new scientific evidence relating to the existence of humans during the Ice Age. He discussed the caves in Belgium and in other parts of Europe where artifacts and human bones had been found with the fossilized bones of Pleistocene animals, as well as the archaeological evidence for a succession of Paleolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages. As a result of his work on human prehistory, in 1890 Fraipont was appointed secretary general of the sixth meeting of the Congrès archéologique et historique [Archaeological and Historical Congress], organized by the Fédération archéologique et historique de Belgique.

Fraipont achieved a great deal of respect and recognition as a professor and researcher by the end of the century. In addition to his many years as a professor of zoology and paleontology, he also served as Dean of the Faculty of Science, and he became rector of the University of Liège in 1909, only months before his death. He was also put in charge of the Museum of Paleontology at the university, where he worked to save and develop Philippe-Charles Schmerling’s huge collection of bones. From 1900, Fraipont and his colleagues Max Lohest, Alfred Habets, Charles-Alfred Gilkinet, and Giuseppe Césaro campaigned to persuade the government to form the degree of engineer geologist at the university. He was a member of many scientific societies and institutions in addition to being a professor at the university. He was a member of the Société géologique de Belgique [Geological Society of Belgium] and served as its president from 1908 to 1909. Fraipont was also a member of the Fédération archéologique et historique de Belgique [Archaeological and Historical Federation of Belgium] and also served as its president. In 1891 he became a member of the Institut Archéologique Liégeois [Archaeological Institute of Liège] and was elected to serve as the Institute’s vice president in 1904 and again from 1908-1909 and served as its president in 1905 and again in 1910 just before his death. He became a corresponding member of the Science Class in the Académie royale de Belgique [Royal Academy of Belgium] in 1895 before being elected a titular member in 1901, and in 1908 he was named director of the Science Class. He was also a member of the Société d’Anthropologie de Bruxelles [Anthropology Society of Brussels] and of the Société Royale des Sciences de Liège [Royal Society of the Sciences of Liège]. He also served as a member of the Commission Académique de la Biographie Nationale [Academic Commission of National Biography]. And as one of the culminating recognitions of his accomplishments as a researcher of human prehistory, he was chosen to be the president of the twenty-first Congrès archéologique et historique when it met in Liège in 1909.

Fraipont was also a member of many foreign scientific institutions. He was elected a foreign member of the Académie impériale allemande Césarine-LéopoIdine-Caroline de Halle in 1890 as well as a corresponding member of the Société impériale des naturalistes de Moscou [Imperial Society of Naturalists of Moscow] in 1895. He was a corresponding member of the École d’Anthropologie [School of Anthropology] in France and of the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien [Anthropological Society of Vienna]. He was also a foreign associate member of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris [Anthropology Society of Paris]. Fraipont also received many awards during his career. He was named a Chevalier of the Order of Leopold in 1899. He received the civic medal first class and the commemorative medal of the reign of His Majesty Leopold II. The Academy of France honored him as an Officer of the Academy France; and the French government awarded him the Légion d’honneur [Legion of Honor] several days before his death. In recognition of his contributions to geology a mineral, fraipontite, was named in his honor.

Julien Fraipont died on 22 March 1910 in Liège following a brief sickness.

Selected Bibliography

“Recherches sur les crinoïdes du famennien (dévonien supérieur) de Belgique.” Third Part. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique 10 (1883): 45-68.

“Recherches sur les crinoïdes du famennien (dévonien supérieur) de Belgique.” Third Part. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique 11 (1884): 105-118.

Julien Fraipont and Ivan Braconier “La poterie en Belgique à l’âge du Mammouth (quaternaire inférieur).” Revue d’Anthropologie 2 (1887): 385-407.

Julien Fraipont and Max Lohest. “La race humaine de Néanderthal ou de Canstadt en Belgique. Recherches ethnographiques sur des ossements humains, découverts dans des dépôts quaternaires d’une grotte à Spy et determination de leur âge géologique,” Bulletins de l’Académie royale de Belgique ser. 3, 12 (1886): 741-784. [This paper also appeared in Archives de biologie, 7 (1887): 587–757].

“Le tibia dans la race de Néanderthal: Etude comparative de l’incurvation de la tête du tibia, dans ses rapports avec la station verticale chez l’Homme et les Anthropoïdes.” Revue d’Anthropologie 3 (1888): 145-158.

Julien Fraipont and Ferdinand Tihon,”Explorations scientifiques des cavernes de la vallée de la Méhaigne,” Mémoires couronnés de l’Académie royale des Sciences de Belgique 43 (1889): 5-72.

“Les Hommes de Spy: La race de Canstadt ou de Néanderthal en Belgique.” Congrès international d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques [1889] (1891): 322-362.

“La race “imaginaire” de Cannstadt ou de Néanderthal. (À la mémoire de A. de Quatrefages.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Bruxelles 14 (1895): 32-44.

Les cavernes et leurs habitants. Paris: J.-B. Baillière et Fils, 1896.

Julien Fraipont and Ferdinand Tihon,”Explorations scientifiques des cavernes de la vallée de la Méhaigne,” Mémoires couronnés de l’Académie royale des Sciences de Belgique 54 (1896): 1-55.

“La grotte du mont Falhise [Anthée].” Bulletin de l’Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique ser. 3, 33 (I897): 47-51.

Les Néolithiques de la Meuse. Bruxelles: Impr. Hayez, 1900.

“Matériaux pour l’histoire des temps quaternaires en Belgique.” Bulletin de l’Académie royale de Belgique (Classe des sciences) (1901): 464-482.

“La Belgique préhistorique et protohistorique.” Bulletins de l’Académie royale de Belgique (1901): 823-877.

“Matériaux pour l’histoire des temps quaternaires en Belgique.” Bulletin de l’Académie royale de Belgique (1901): 463-482.

“Les origines de la sculpture, de la gravure et de la peinture chez l’homme fossile.” Bulletin de l’Institut archéologique liégeois 34 (1904): 333-338.

Other Sources

Laurent-Guillaume de Koninck, “Faune du calcaire carbonifère de la Belgique. Part 5 Lamellibranches.” Annales du Musée royal d’ histoire naturelle de Belgique (1885)

Secondary Sources

Lucien Renard, “Julien Fraipont,” Chronique archéologique du Pays de Liège 5 (1910): 27-38.

Paul Fourmarier, “Notice biographique sur Julien Fraipont.” Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique 41 (1914): 337-350.

M. Lohest, Charles Julin et A. Rutot, “Notice sur Julien Fraipont, membre de l’Académie.” Annuaire de l’Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique 91 (1925): 130-197.

Georges Ubaghs, “Julien Fraipont.” In Bibliographie nationale, vol. 38, supplement vol.10, pp. 221-224. Brussels: Émile Bruylant, 1973.

Michel Toussaint, Les hommes fossiles en Wallonie: de Philippe-Charles Schmerling à Julien Fraipont, l’émergence de la paléoanthropologie. Namur: Ministère de la Region Wallonne, Division du Patrimoine, 2001.

Annick Anceau, Cyrille Prestianni, Frederic Hatert, and Julien Denayer “Les sciences géologiques à l’Université de Liège: deux siècles d’évolution. Partie 1: de la fondation à la Première Guerre Mondiale.” Bulletin de la Société Royale des Sciences de Liège 86 (2017): 27-63.