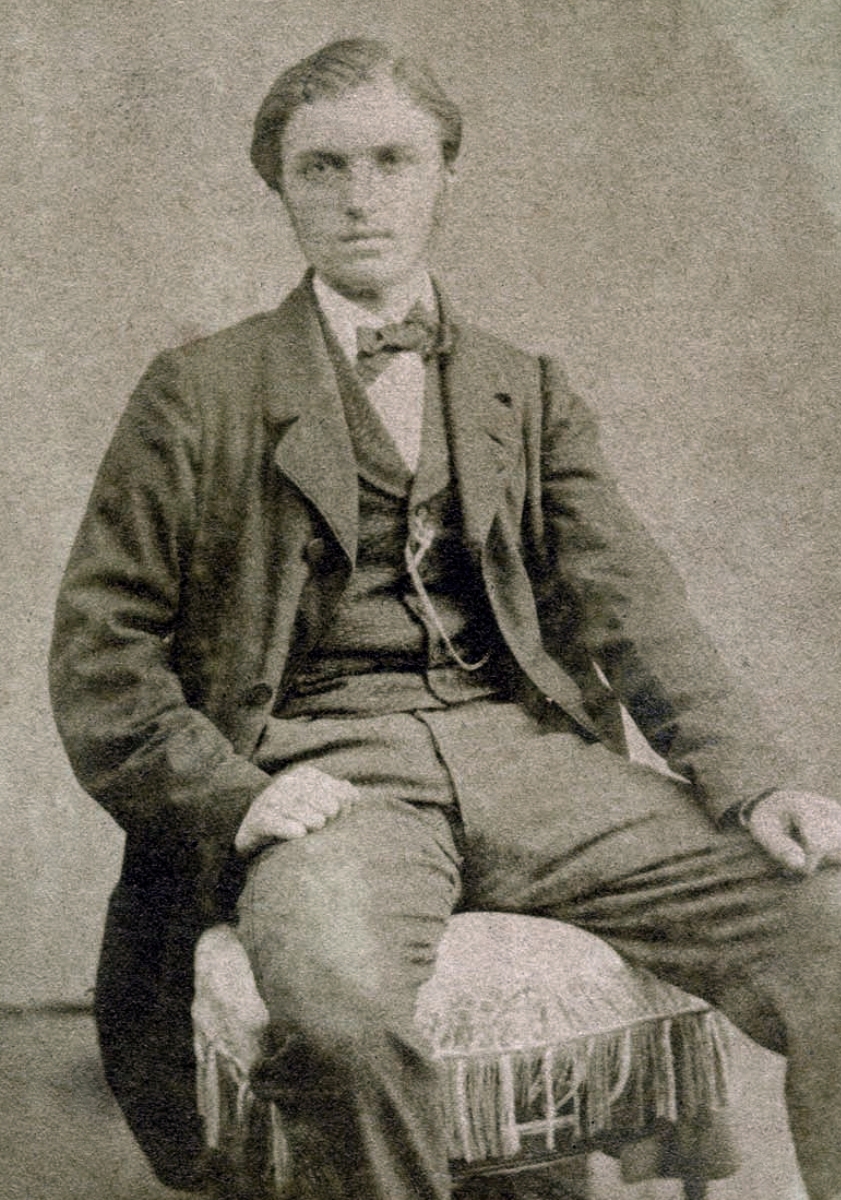

Louis Lartet (1840-1899)

Matthew Goodrum

Louis-Marie-Hospice Lartet was born in Castelnau-Magnoac, in the southwest of France, on 18 December 1840. His father, Édouard Lartet, was a geologist and prehistorian who played an important role in establishing the study of Ice Age humans in France. During the 1860s, Édouard Lartet and the English banker Henry Christy explored caves and rock shelters in the Vézère valley where they found Paleolithic artifacts and animal figures carved from ivory and reindeer antler. Louis Lartet grew up wandering the countryside around the family home in the department of Gers, where he developed an interest in nature and especially for collecting shells and fossils. The latter led him to pursue studies in geology. Lartet studied for two years at the lycée in Toulouse beginning in 1852, but the family later moved to Paris where his father cultivated relationships with many leading French scientists.

Lartet’s geological career advanced significantly during the 1860s when he was offered several valuable research opportunities. He became an assistant (préparateur) at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History) in October 1862, which placed him in one of the most important scientific institutions in the country. That same year, he was invited to join the French paleontologist Édouard de Verneuil on a geological expedition in Spain. While there Verneuil and Lartet, accompanied by the Spanish geologist Casiano de Prado, visited the archaeological site of San Isidro, in Madrid, where they found a Paleolithic flint axe in Pleistocene deposits. Verneuil and Lartet published a paper on this artifact, which was significant because it was the first evidence for Ice Age humans found in Spain (Verneuil and Lartet 1863). Lartet became a member of the Société Géologique de France (Geological Society of France) in 1863. The following year, he was offered an opportunity to join an expedition organized by a French aristocrat, the Duc de Luynes.

Honoré-Théodoric-Paul-Joseph d’Albert de Luynes was a scholar with an interest in both history and archaeology. The purpose of de Luynes’ expedition was to explore Palestine and surrounding regions and especially to investigate the origin of the Dead Sea. Lartet was responsible for conducting geological research during the expedition, which lasted from February 1864 to June 1865. While investigating the deposits along the Dead Sea, Lartet took the opportunity to collect information on the archaeology of the region as well. He studied the dolmens located along the Dead Sea at the ancient site of Ammonitide, at Manfoumieh near Mount Nebo, and at Djebel Attarus. These monuments consisted of four large stones forming the sides of the dolmen, with a circular opening forming an entrance, and one stone covering the top. He also explored the extensive Roman ruins and the necropolis at Um-Keis, the site of the ancient city of Gadara, located near the Sea of Galilee. When the expedition traveled to Syria, Lartet conducted excavations at Nahr el Kelb, where he unearthed flint knives and other stone tools as well as broken bones belonging to animals that were either extinct or that no longer lived in the region. Lartet also found stone tools along the coast of Lebanon during this expedition.

The geological research that Lartet conducted during this expedition served as the subject of his doctoral thesis, titled Essai sur la géologie de la Palestine et des contrées avoisinantes telles que l’Egypte et l’Arabie: comprenant les observations recueillies dans le cours de l’expédition du duc de Luynes à la Mer Morte (Essay on the Geology of Palestine and Neighboring Countries such as Egypt and Arabia), which was submitted to the faculty of sciences at the University of Paris in 1869. The thesis was published in the journal Annales des sciences géologiques and also appeared as a book. The second part of this work, which dealt with paleontology, was delayed by the onset of the Franco-Prussian War and was not published until 1872 (both in the Annales des sciences géologiques and as a book. Lartet later published Exploration géologique de la Mer Morte, de la Palestine et de l’Idumée (Geological Exploration of the Dead Sea, Palestine, and Idumea) (1876), which discussed the geology and paleontology of Palestine. In this book, he included a chapter that discussed the new evidence pertaining to human prehistory in the region. The discovery of Stone Age artifacts in this region was significant because it was seen as the cradle of civilization by many scholars, who thought that civilization had been introduced into a culturally and technologically less advanced prehistoric Europe from a civilized Orient. Lartet had to deal with the topic of human prehistory in the Holy Land cautiously given its implications for biblical notions of human history since this was potentially a sensitive subject for the church.

After his return from the Dead Sea expedition in 1865, Lartet accompanied his father on a trip to Spain. Louis examined caves in Álava and the Cameros Mountains, but ill health prevented Édouard from participating in this work. Louis explored twenty caves in the area around Torrecilla de Cameros; including a collection of caverns called the Lóbrega Cave. He collected animal bones as well as stone tools from caves at Peña de la Miel, which he attributed to the Reindeer Age. He also unearthed human bones, stone tools, and pottery from the Lóbrega Cave, which he dated to the late Stone Age (Lartet 1866; see also Pelayo López and Gozalo Gutiérrez 2013). The German anthropologist Franz Ignaz Pruner-Bey, living in Paris at the time, published a description of these artifacts and human bones (Pruner-Bey 1866). Lartet was becoming increasingly involved in the study of Ice Age humans. Throughout the 1860s, Lartet and periodically assisted his father with the excavation of Paleolithic sites in the Vézère valley. Lartet became involved with the Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistoriques (International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology) soon after it was first conceived in 1866. These were meetings that brought together geologists, paleontologists, archaeologists, and anthropologists from across Europe to discuss the many new discoveries being made about human prehistory. Lartet served as the secretary of the third meeting of the Congress when it met in England, at Norwich and London, in 1868.

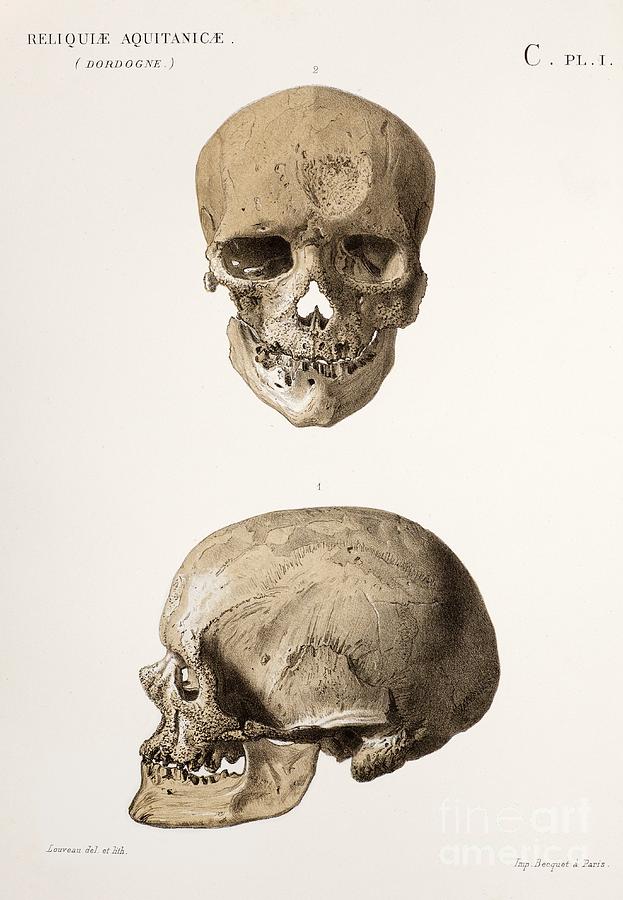

Lartet is best known for his excavations at the Cro-Magnon rock shelter near the village of Les Eyzies. During construction of a railroad through the village in March 1868, workmen dug into the floor of the rock shelter where they encountered artifacts and human bones. After the authorities were informed and the scientific importance of the site was recognized, Victor Duruy, from the Ministry of Public Education, asked Lartet to conduct a thorough excavation. He unearthed artifacts made from flint, ivory, and reindeer antler, but most importantly he recovered four partial human skeletons and one infant skeleton. Lartet’s task was to confirm the authenticity of these objects and to determine their geological age. The animal bones from the site, which included mammoth and reindeer, were studied by Édouard Lartet and indicated that the human remains dated to the end of the Pleistocene. Lartet presented a paper on his discoveries at Cro-Magnon on 21 May 1868 at the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (Anthropology Society of Paris) and published a paper defending the geological antiquity of the human skeletons (Lartet 1868a; 1868b). The idea that humans lived during the Ice Age was a recent and still controversial idea. Geologists had only found a small number of human bones in Pleistocene deposits to this point and the skeletons from Cro-Magnon offered invaluable information regarding who these Ice Age people were. Several prominent anthropologists, including Franz Ignaz Pruner-Bey (1868a; 1868b), Paul Broca (1868a; 1868b), and Armand de Quàtrefages and Ernest-Théodore Hamy (1874) examined the skeletons and concluded that they belonged to a distinct race of people who lived in Europe during the Ice Age.

In 1869 Lartet resigned from his position as assistant at the Museum of Natural History to become a préparateur at the Sorbonne. His career was on an upward trajectory following his successful completion of the excavations at Cro-Magnon, but then several disasters befell him. The first was the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), which caused Lartet to leave Paris, and during the war, he served as a sergeant-major in Gers. Lartet suffered considerable stress as a result of the war, which was compounded by the death of his father in 1871. These two events deeply affected Lartet and seem to have disrupted the course of his career. At the end of the war, he returned to Paris, but he soon left for the south of France. Once more Lartet was called upon to supervise excavations following yet another discovery of Ice Age human remains found in a rock shelter in the Pyrenees.

The events that prompted this began in 1872 when Raymond Pottier, a member of the Société Française d’Archéologie (French Society of Archaeology), found Stone Age artifacts in Landes and Chalosse. Pottier then enlisted the assistance of Gatien Chaplain-Duparc in the excavations. Chaplain-Duparc was a former officer of the merchant navy, and in his many travels throughout the world, he had collected ethnographic and archaeological objects. French anthropologist Ernest-Théodore Hamy had encouraged Chaplain-Duparc to excavate caves in the Pyrenees, and he had examined the tumulus of Garin, near Luchon, as well as excavating several caves near Lorthet. Pottier and Chaplain-Duparc began excavating the rock shelter of Duruthy, located near Sorde (Basses-Pyrénées) in 1873. In addition to artifacts, they unearthed a human skeleton, and when a second skeleton was discovered on 12 January 1874 ,Lartet was called in to take over the excavations. In the lowest strata of the rock shelter Lartet and Chaplain-Duparc recovered parts of a human skeleton, including a skull, along with a necklace made from cave lion and cave bear teeth. Immediately above this was a charcoal layer containing Magdalenian artifacts including arrowheads associated with animal bones. Above this was a layer containing human bones belonging to more than thirty individuals along with flint implements (Lartet and Chaplain Duparc 1874). The results of the excavations at Duruthy were presented at the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris on 18 June 1874 and a month later at the meeting of the Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistoriques held in Stockholm, Sweden. These discoveries were important because they provided later researchers with evidence regarding the material culture and the inhabitants of France spanning the period from the so-called Reindeer Age (during the late Paleolithic) to the Neolithic.

Lartet accepted a position teaching geology at the University of Toulouse in 1873. Initially his appointment was as a suppléant or lecturer in the Faculty of Sciences, but in 1879 he was promoted to Chair of Geology and Mineralogy at the university when Alexandre Leymerie retired. Lartet devoted his time to teaching and studying the geology of the Pyrenees. He also undertook the massive task of organizing the mineralogy and paleontology collections of the Faculty of Science in a new building at the university. Lartet served as an important member of the Council of the University of Toulouse for a number of years. Lartet saw to the completion and publication of the Description géologique et paléontologique des Pyrénées de la Haute-Garonne in 1881, which his predecessor Alexandre Leymerie had left unfinished.

Lartet was a member of several local and national scientific societies. He became a member of the Société Géologique de France in 1863 and of the Société Archéologique du Midi de la France in 1874. He became a member of the Société d’Agriculture de la Haute-Garonne in 1880, of the Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres de Toulouse in 1882, and of the Société d’Histoire Naturelle de Toulouse in 1883. He was also a member of the Société Archéologique, Historique, Littéraire et Scientifique du Gers. Lartet was elected a Foreign Correspondent of the Geological Society of London in 1882. Lartet retired as a professor at the University of Toulouse due to poor health in 1899 and returned to Seissan, in Gers, where he died in his family home in August. None of the obituaries published at the time give the date of this death, but his funeral was held on 16 August 1899.

Selected Bibliography

Edouard de Verneuil and Louis Lartet, “Note sur un silex taillé trouvé dans le diluvium des environs de Madrid.” Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 20 (1863): 698-702.

“Note sur la découverte de silex taillés en Syrie accompagnée de quelques remarques sur l’âge des terrains qui constituent la chaîne du Liban.” Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 22 (1865): 537-545.

“Poteries primitives, instruments en os et silex taillés des cavernes de la Vieille Castille (Espagne).” Revue archéologique 13 (1866): 114-134.

“Sur les grottes du bassin de l’Èbre (Espagne) où sont trouvés des ossements de mammifères fossiles et de vestiges de l’industrie humaine”. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 23 (1866): 718.

“Sur les découvertes relatives aux temps préhistoriques faites en Palestine.” Compte rendu de la Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistoriques [1867] (1868): 115-119.

“Mémoire sur une sepulture des anciens troglodytes du Périgord.” Annales des sciences naturelles: Zoologie et paléontologie ser 5, 10 (1868a): 133-45.

“Une sépulture des troglodytes du Périgord,” Bulletins de la Société ’Anthropologie de Paris 3 (1868b): 335-349.

Essai sur la géologie de la Palestine et des contrées avoisinantes, telles que l’Egypte et l’Arabie: comprenant les observations recueillies dans le cours de l’expédition du duc de Luynes à la Mer Morte. Paris: V. Masson, 1869.

“Une sépulture des troglodytes du Périgord à Cro-Magnon”, suivi de “Remarques sur la faune de Cro-Magnon”. Matériaux pour l’histoire naturelle et primitive de l’homme, V, pp. 97-108, 7 fig. (English translation in Lartet E. et Christy H., Reliquiae Aquitanicae).

Essai sur la géologie de la Palestine et des contrées avoisinantes, telles que l’Egypte et l’Arabie: comprenant les observations recueillies dans le cours de l’expédition du duc de Luynes à la Mer Morte. Part 2: Paléontologie. Paris: Masson, 1873.

“Traces de l’homme préhistorique en Orient.” Matériaux pour l’histoire naturelle et primitive de l’homme 8 (1873): 177-194.

“Gravures inédites de l’âge du renne paraissant représenter le Mammouth et le Glouton.” Matériaux pour l’histoire naturelle et primitive de l’homme 9 (1874): 33-36.

Louis Lartet and Chaplain-Duparc, “Sur une sépulture des anciens Troglodytes des Pyrénées superposée à un foyer contenant des débris humains associés à des dents sculptées de lion et d’ours.” Matériaux pour l’histoire primitive et naturelle de l’homme 9 (1874): 101-67. 302-330

Honoré d’Albert Luynes, duc de; Ch Mauss; Henri Joseph Sauvaire; Louis Marie Horpice Lartet; Louis Vignes; marquis de Melchior Vogüé, Voyage d’exploration à la mer Morte, à Petra, et sur la rive gauche du Jourdain. 3 volumes. Paris: A. Bertrand, 1874. (Volume 3 on geology is written by Lartet).

“Sur un atelier de silex taillés et une dent de Mammouth trouvés près de Saint-Martory, aux environs d’Aurignac (Hte-Garonne).” Matériaux pour l’histoire naturelle et primitive de l’homme 10 (1875): 272-275.

Exploration géologique de la Mer Morte de la Palestine et de l’Idumée. Paris: A. Bertrand, 1876.

Other sources

Franz Ignaz Pruner-Bey. “Description sommaire des restes humains découverts dans les Grottes de Cro-Magnon, prés de la station des Eyzies, arrondissement de Sarlay (Dordogne), en Avril 1868.” Annales des sciences naturelles: Zoologie et paléontologie ser 5, 10 (1868): 145-155.

Franz Ignaz Pruner-Bey, “Sur les ossements humains des Eyzies.” Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 3 (1868): 416-446.

Paul Broca, “Sur les crânes et ossements des Eyzies.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 3 (1868): 350-392.

Paul Broca, Description sommaire des restes humains découverts dans les grottes de Cro-Magnon près de Les Eyzies, Annales de Sciences naturelles, Zoologie et Paléontologie 10 (1868): 145-155.

Armand de Quàtrefages and Ernest Théodore Hamy. “La race de Cro-Magnon dans l’espace et dans le temps.” Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 260-266.

Francisco Pelayo López and Rodolfo Gozalo Gutiérrez, “Confirming Human Antiquity: Spain and the Beginnings of Prehistoric Archaeology.” Complutum 24 (2013): 43-50.

Secondary Sources

E. C., [Obituary for Louis Lartet] Revue des Pyrénées 11 (1899): 601-602.

Marcellin Boule, “Mort de Louis Lartet.” L’Anthropologie 10 (1899): 497-498.

E. de Margerie, “Éloge de Louis Lartet.” Bulletin de la Société géologique de France ser. 3, 28 (1900): 511.

A. Lavergne, “Louis Lartet.” Revue de Gascogne 41 (1900): 177-182,

Emile Cartailhac, “Eloge de Louis Lartet.” Mémoires de la Société Archéologique du Midi de la France 16 (1903): 9-18.

Père André. “Louis Lartet (1840-1899) fils et digne successeur d’Édouard Lartet.” Bulletin de la Société Archéologique, Historique, Littéraire et Scientifique du Gers 72 (1971): 458-467.

A. M. Monseigny and A. Cailleux, “Lartet, Louis.” In Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Charles Gillispie (ed.). Vol. 8, pp. 44-45. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1981.

G. Laurent, “Louis Lartet 1840-1899.” In Dictionnaire du Darwinisme et de l’Évolution (p. tOrt, dir.), puF, paris, (1996) II: 2582-2583