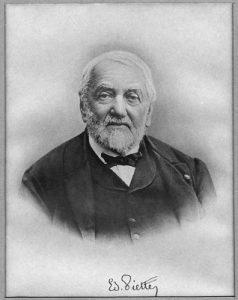

Edouard Piette (1827–1906)

Matthew Goodrum

Louis-Edouard-Stanislas Piette was born on 11 March 1827 at Aubigny, in the Ardennes region of France near the border with Belgium. His father, Louis-Auguste Piette, was a notaire (a public official authorized to certify legal documents) in Aubigny and later served as mayor of Rumigny, and his mother was Anne Henriette Stéphanie Lhoste. The family later moved to Charleville when Piette’s father was appointed conseiller général of the Ardennes. Piette studied at the college in Charleville where he and his brother Henry roamed the countryside collecting plants, insects, and fossils from the local quarry. After a year studying at Metz, he and Henry became clerks preparing to be notaires in Charleville. After three years, they went to Paris where they attended courses in the natural sciences at the Sorbonne, the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (Museum of Natural History), and at the École des Mines (School of Mines). Following his father’s wishes Piette obtained a degree in law in 1852 and returned to the Ardennes where he registered as a lawyer at the bar of Rocroi. He married Emilie Jenny Clémentine Graux, and they had two daughters, Marie and Louise.

In addition to establishing a career as a lawyer, in 1858 Piette published Education du Peuple (Education of the People), a book that advocated compulsory and secular education, as well as the teaching of morality that was not based in any specific religious denomination. Meanwhile, he was appointed justice de paix (justice of the peace) first in Raucourt in 1860, then at Rumigny in 1861, Asfeld in 1864, and at Craonne in 1868. His independent nature brought negative attention from government authorities, and this may help explain his frequent transfers to new locales. Through the intervention of his friend, the famous historian Henri Martin, he was appointed a judge in the civil court in 1882, a position he held at several places throughout France (Eauze, Gers, Segré, Le Mans, Angers), which allowed him to pursue his scientific interests in many different regions of France.

While successfully serving as a magistrate and judge, Piette never lost his original interest in the natural sciences, and despite the demands of his official duties, he found time to pursue a range of scientific endeavors. From an early age, Piette was interested in natural history, particularly paleontology and geology. From 1860 to 1870 he and the French pharmacist and paleontologist Olry Terquem studied the geology of the Aisne, the Ardennes, the Meuse, and the Moselle as well as sandstone deposits in Luxembourg (Terquem and Piette 1865). He assembled a large collection of Bathonian fossils from the Jurassic period, and he contributed a volume on the Jurassic gastropods he had collected to the series on French paleontology instigated by Alcide d’Orbigny (Piette 1891). Beyond these geological researches, Piette also became interested in prehistoric archaeology. While serving as justice de paix in Craonne, he and Edouard Fleury explored the necropolis in Çhassemy called Le Dessus de Prugny. Working at the site from 1868 to 1869, they distinguished three layers of burials dating to the Neolithic and the early Iron Age. Piette also examined a dolmen in Rumigny in 1870, the only monument of this kind that was known at that time in the Ardennes.

After enduring the upheaval of the Franco-Prussian War, Piette was encouraged to travel to the spa town of Bagnères-de-Luchon in the southwest of France, at the foot of the Pyrenees, for rest and to take the mineral waters in order to recover from the stress that had weakened his health. While there he studied the Pleistocene glaciers of the valley of the Garonne and the Pique rivers. He also met the French geologist Edouard Lartet who was engaged in excavating Paleolithic archaeological sites in the Vézère valley and this meeting spurred Piette to search for Paleolithic sites in the caves of southwest France. Thus began a long period, from 1871 to 1897, when Piette excavated the Upper Paleolithic sites of Gourdan, Lortet, Mas d’Azil, and Brassempouy. These investigations produced a remarkable collection of carved and engraved pieces of bone and ivory that made Piette one of the leading experts on Paleolithic art. Piette pursued this research in his free time and financed the excavations from his own personal wealth. According to the French archaeologist Émile Cartailhac, who was Piette’s friend and colleague, Piette spent several thousand francs each season for the rights to excavate these sites and to pay teams of laborers to conduct the work. In addition to the practical challenges he confronted in this research, when news spread of his spectacular finds, antique dealers sometimes raided his excavations at night to steal artifacts (Cartailhac 1906).

The first site that Piette investigated was the cave at Gourdan, located near the town of Montrejeau in Haute-Garonne. In 1871 Piette and Charles Fourcade, a naturalist from Bagnères-de-Luchon, initiated the first excavation and soon found artifacts. Piette worked at Gourdan from 1871 to 1875, and he employed the skills and methods he had learned as a geologist to carefully explore each layer of the cave in order to produce a stratigraphic record of its deposits. These deposits contained animal bones (especially reindeer), tools made from flint and bone, but even more exciting were pieces of bone and reindeer antler carved with images of animals. These included reindeer, stag, goats, bison, horses, and other animals. The carved images from the lower layers at Gourdan were finely executed and were realistic depictions of animals, but the carvings from the upper layers were crudely made and differed markedly from the older artifacts. In addition to these artifacts, Piette also found human bones, including a partial upper jaw, a fragment of a mandible, and skull fragments. All of the human bones were badly broken and reduced to small fragments. Most had notches and incisions on them, which Piette interpreted as evidence of cannibalism. Ernest-Théodore Hamy, an anthropologist at the Museum of Natural History in Paris and curator of the Musée d’Ethnographie (Museum of Ethnography), later published a description of the human bones from Gourdan (Hamy 1889). Piette presented several papers at the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (Anthropology Society of Paris) describing his discoveries at Gourdan (Piette 1871; 1873; 1875), but soon his attention was drawn to other sites.

In 1873 Piette began excavating a cave called the grotte de Lortet, located in the Hautes-Pyrénées, with the assistance of prehistoric archaeologist Émile Cartailhac and Eugène Trutat, curator of the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Toulouse. They unearthed flint tools, finely made harpoons along with a range of other tools made from bone and antler, and once again pieces of bone and antler with engraved figures of animals (Piette 1874). Piette attributed the artifacts from Gourdan and Lortet to what French archaeologists frequently called the Reindeer Age (‘âge du renne), but the French archaeologist Gabriel de Mortillet had recently designated his period the Magdalenian (de Mortillet 1869; 1872). Piette also excavated a cave called the grotte d’Espalungue at Saint-Michel, in Arudy in the department of Pyrénées-Atlantique, during 1873 and 1874. He uncovered several stratigraphic layers containing animal bones, flint tools, harpoons made from antler, bone and antler tools, bas-relief sculptures and engraved horse heads from the Magdalenian period. By comparing the artifacts and animal fossils from Gourdan and Lortet, combined with his careful stratigraphic analysis of the cave deposits, Piette was able to demonstrate that they did not all belong to the same precise geologic period, despite clearly belonging to the so-called Reindeer Age. This was one of the first indications that the Reindeer Age was of very long duration and was more complex than archaeologists thought.

His frequent transferal from one post to another often disrupted his research and was the cause for some frustration, but it also meant that he could explore the prehistoric ruins of new areas. During the 1870s, Piette began a fruitful collaboration with Julien Sacaze, a lawyer in the town of Saint-Gaudens, in Haute-Garonne. Sacaze was also an archaeologist and historian who published many works on the early history of the region along the Pyrenees in southwest France, and so was familiar with many prehistoric monuments. Piette and Sacaze investigated the cromlech and tumuli at Mount Epiaup during 1875 and 1876 (Piette and Sacaze 1877). In 1877 and 1878, they excavated the Iron Age tumulus of Avezac Prat (Hautes-Pyrénées) on the Lannemezan plateau, which contained a cremation burial and beautifully made urns (Piette and Sacaze 1879). From 1877 to 1880, Piette and Sacaze investigated the Neolithic and Bronze Age tumuli that lay between the towns of Bartrès, Ossun, Gers, and Lourdes, including the tumulus of Pouy Mayou which they excavated during the winter of 1879-1880 (Piette 1881a; 1884). Piette also appears to have joined Sacaze in the exploration of the early Iron Age incineration burials at Bordes-de-Rivière in 1880. In addition, when Piette was appointed justice of the peace in the town of Eauze, in the department of Gers, in 1879 the Ministry of Public Education directed him to explore the Gallo-Roman monuments that had been uncovered there as the result of the construction of a railroad. Eauze was built on the site of the Roman city of Elusa, which had been capital of the Roman province of Novempopulania, and Piette was able to collect antiquities and record Roman inscriptions from the site (Piette 1881b).

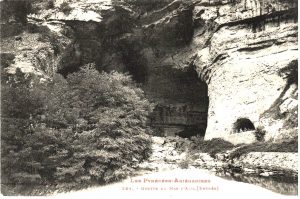

One of Piette’s most influential excavations was conducted at the site of Mas d’Azil. Near the village of Mas d’Azil, which lies at the foothills of the Pyrenees in Ariège, there exists an enormous tunnel in the rock through which the Arize River flows. There are caves and galleries lying along the tunnel that contained deep geologic deposits. Repair to the nearby road had unearthed new deposits in the tunnel, and these attracted the attention of Piette in 1887. He conducted careful excavations, recording the stratigraphy of the site. Piette unearthed layers dating from the Iron Age that contained animal bones and pottery, and below these were Bronze Age and Neolithic layers containing artifacts and the bones of domesticated animals. Still deeper there were deposits dating from the Reindeer Age (the Magdalenian period). The upper layers of these Magdalenian deposits contained flint tools and stag horn harpoons, but the lower layers contained reindeer antler harpoons and many pieces of carved bone and ivory depicting bison, horse, deer, and even a human figure. When Piette explored the deposits on the left bank of the river, he found red painted pebbles along with flint artifacts that resembled Magdalenian tools. He also found many flattened double-barbed harpoons made of stag antler, which differed from Magdalenian harpoons, which were rounded and made of reindeer antler. The most significant fact about these deposits was that there were no reindeer fossils and the animal bones all belonged to species that inhabited France after the retreat of the glaciers at the end of the Ice Age. This meant that these deposits and the artifacts they contained dated to a time after the end of the Paleolithic but were older than the Neolithic.

At this time, many prominent prehistorians believed there was a discontinuity between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic periods in Europe. They believed the Paleolithic population had disappeared as a result of the retreat of the glaciers and the disappearance of the Ice Age fauna and that Neolithic newcomers entered Europe a long period of time after this. Gabriel de Mortillet and Émile Cartailhac were among the French scientists who supported this idea, as did William Boyd Dawkins and others in Britain. On the basis of the objects he collected at Mas d’Azil, Piette argued that he had discovered a transition period between the Paleolithic and Neolithic. He called this period the Azilian, and he presented his evidence for this transitional period to the Académie des Sciences (Piette 1889) and in an important paper titled “Hiatus et lacune: Vestiges de la période de transition dans la grotte du Mas-d’Azil” (Piette 1895a). Piette knew his discovery of a transitional period between the Paleolithic and Neolithic would be controversial so he invited members of the Société géologique de France (Geological Society of France) to inspect the site and its stratigraphy. The paleontologist Marcellin Boule was the Society’s secretary at that time, and he traveled to Mas-d’Azil to inspect the site and its artifacts in situ, coming away convinced of the validity of Piette’s claims. This also marked the beginning of a long professional relationship between the two men.

In the course of the excavations of this transitional “Azilian” layer at Mas-d’Azil, Piette unearthed a burial containing two partial skeletons whose bones were covered with red ochre. But scientists found the painted pebbles that Piette collected in this Azilian layer, small stones bearing red markings painted on them, particularly intriguing. Piette eventually came to believe that the symbols on these pebbles represented objects, words, and even whole sentences. He even suggested that these enigmatic symbols had provided the elements of the most ancient alphabets of the Bronze Age, appearing partly in Trojan, Cyprian, and Aegean writing; but especially visible in the alphabets of the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Italians (Piette 1905). Several institutions, including the British Museum, obtained specimens of these painted pebbles, but after Piette’s death, convincing evidence appeared that some of the painted pebbles were forgeries made by workmen.

The last site that Piette explored was a cave called grotte du Pape at Brassempouy. The Paleolithic site at Brassempouy had already been the subject of several excavations. Pierre-Eudoxe Dubalen, a pharmacist and amateur archaeologist, found Upper Paleolithic artifacts during excavations in 1880 and 1881. Joseph de Laporterie, a lawyer, archaeologist and historian from Landes, resumed excavations at Brassempouy in 1890. Piette and de Laporterie worked at the site from 1894 to 1897, unearthing several layers containing Magdalenian artifacts along with mammoth and rhinoceros fossils. They also found pieces of bone and ivory engraved with images of horses, and in one layer, they found five beautiful ivory statuettes. The most famous of these is the “Dame à la Capuche,” a female figure carved from steatite, which they discovered in 1894.

Over the course of many years excavating sites along the Pyrenees, Piette had accumulated a remarkable collection of Upper Paleolithic artifacts, especially sculpted and engraved pieces of bone and ivory. Piette displayed some of his Paleolithic art objects at the Exhibition Universelle held in Paris in 1878. Among those who attended the Exhibition was Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, a Spanish lawyer and landowner with an interest in prehistory. Sanz de Sautuola had begun to explore the cave of Altimira, in the north of Spain, in 1875 with the hope of finding prehistoric artifacts. He met with Piette during the Exhibition, and Piette advised him on how to excavate prehistoric caves. In 1879 Sanz de Sautuola discovered images of Ice Age animals painted on the walls in the rear of the cave. Although many anthropologists rejected the authenticity of the cave paintings at Altamira, Piette wrote a letter to Cartailhac in 1887 arguing that they were authentic Magdalenian art. Piette displayed his growing collection of Paleolithic art at the 1889 Exhibition Universelle in Paris and again at the 1900 Exhibition Universelle where his collection on display at the Trocadéro Palace drew large crowds.

Prior to Piette’s excavations at Gourdan, Lortet, Mas-d’Azil, and Brassempouy, geologists and paleontologists had difficulty in distinguishing the Reindeer Age from older Paleolithic deposits. Yet it was clear to researchers that it was an important period in human prehistory. Before Piette it was not possible to imagine that the Reindeer Age could be divided into periods, but his research provided stratigraphic, paleontological, and archaeological evidence of a succession of changes during the Reindeer Age that indicated a long duration of time. Indeed, because Piette had experience as a geologist, he was careful to record the stratigraphy of the sites he excavated. This allowed him to reconstruct the relative chronology of their deposits. Over the years, Piette proposed several schemes for dividing the Paleolithic into periods. The French prehistorian Gabriel de Mortillet had already proposed a sequence of periods within the Paleolithic (Chellean, Mousterian, Solutrean, and Magdalenian) based largely on the types of artifacts found in French Paleolithic sites (de Mortillet 1883). Piette’s method for dividing the Paleolithic into periods differed in important ways from that of de Mortillet. Piette stressed the importance of relying upon stratigraphy, combined with paleontological and ethnographic evidence. These criteria took precedence over the typological method that de Mortillet employed.

As early as 1889, Piette proposed dividing the Paleolithic into a series of epochs (Achéolienne Mostérienne Sulistrienne, Magdalénienne). He also subdivided the Magdalenian into a series of phases on the basis of animal fossils: Elaphienne (red deer); Tarandienne (reindeer); Hippiquienne (horse); and Bovidienne (ox). In other works, he describes an époque sulistrienne (characterized by Solutrean artifacts and a fauna of spotted hyena, mammoth, auroch, and horses); an époque éburnéenne (characterized by Magdalenian artifacts and ivory sculptures, with a fauna of auroch, mammoth, Rhinoceros tichorinus, lion, panther); and an époque tarandienne (that part of the Magdalenian characterized by artifacts and sculpture made from reindeer antler and a fauna of ox, aurochs, reindeer, red deer, horse, wild boar, badger, fox, wolf). Alternatively, Piette proposed subdividing the French Paleolithic into an Amygdalithic period (characterized by hand axes and correlated with de Mortillet’s Chellean and Acheulean), a Niphetic period (de Mortillet’s Mousterian), and a Glyptic period (characterized by the presence of art objects). However, Piette’s periodization schemes and his nomenclature for these periods were not widely adopted by European archaeologists.

Perhaps more influential was his proposal of an âge glyptique (Glyptic Age), which referred to the period at the end of the Paleolithic that was characterized by fine art objects of carved or engraved bone and ivory as well as cave paintings; and of an âge asylien (Azilian Age) that fell between the end of the Magdalenian period, at the end of the Paleolithic and the beginning of the Neolithic. In other words, it represented the period after glaciers had retreated and the reindeer and other Ice Age animals no longer live in France. This period was characterized by the colored pebbles and other artifacts Piette had found at Mas d’Azil. Several prominent archaeologists adopted this periodization and nomenclature during the early twentieth century, but Piette’s Azilian period was later largely subsumed into the idea of a Mesolithic period. In his important monograph on Paleolithic art, Piette proposed a series of phases of the development of art during the Glyptic Age based on faunal evidence and changes in the art: Elaphienne, Rangiférien (or Tarandienne), Hippiquienne, and Eléphantien (or éburnéen) (Piette 1907). Beyond these attempts to trace a chronological series of phases for the Upper Paleolithic, Piette also drew important conclusions about the development of Paleolithic culture and art.

Regarding the evolution of Upper Paleolithic art, Piette argued that sculpture preceded figures carved in relief, and these preceded designs engraved onto the surface of bone and stone. He also believed that naturalistic and realistic depictions of animals represented the first forms of art but that later more abstract depictions appeared. Piette conducted important studies of the changing form of harpoons from the Upper Paleolithic into the Azilian (Mesolithic) period in France (Piette 1895d). Interestingly, Piette suggested that sculptured figures of humans could be used to identify the human races that lived in France during the Paleolithic. This was rooted in his belief that Paleolithic art presented realistic depictions of nature. For example, he argued that a steatophagous female figurine excavated at Brassempouy indicated that an African “Bushman race” (“race bochimane”) existed in France during the Upper Paleolithic. Piette argued that during the Glyptic Age there were three races in France: Neanderthal, Somali, and European (Piette 1902). At a time when European archaeologists and anthropologists were debating the cultural and intellectual abilities of Paleolithic peoples, whether they were primitive savages or people possessing a rudimentary civilization, Piette was convinced that the high quality of Upper Paleolithic artifacts and art objects indicated that these peoples were not uncultured savages but possessed an admirable culture and civilization.

By the 1890s, Piette had collected more than 300 art objects and a large number of artifacts from the sites he had excavated. He had published numerous papers covering a range of topics, but the demands of serving as a judge and the relentless sequence of excavations at Mas d’Azil and Brassempouy prevented him from finishing a monograph on his discoveries. As a consequence, in 1891 Piette requested that he be appointed an honorary judge, thus allowing him to retire back to Rumigny and devote all his time to writing papers and working on a book about Paleolithic art. It was at this time that Marcellin Boule invited Piette to write a series of articles on prehistoric ethnography for the journal L’Anthropologie. The result was a series of nine papers (under the heading “Études d’ethnographie préhistorique”) published between 1895 and 1906 covering topics ranging from plant cultivation during the Mesolithic at Mas-d’Azil, the semi-domestication of horses and reindeer during the Magdalenian, the colored pebbles from Mas-d’Azil, and the discoveries at Brassempouy. As Piette composed the text for his monograph on Upper Paleolithic art, he sought the collaboration of the skilled draughtsman Henri Formant, who worked at the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, to produce illustrations of the many pieces of Paleolithic art in Piette’s collection. Piette enlisted Jules Pilloy, a master of the technique of chromolithography, to produce the beautiful color plates that appeared in the book. Unfortunately, integrating the new discoveries from Mas d’Azil and Brassempouy caused delays and Piette died before the book was finished. The posthumous publication of L’art pendant l’âge du Renne (Art during the Reindeer Age) was left to Piette’s son-in-law Henri Fischer, and it appeared in 1907. The book offered one of the most extensive studies of Paleolithic art yet published. In it Piette presented the latest version of his chronological division of the Paleolithic and the chronological phases of the development of Upper Paleolithic art. But the most significant feature of the book was the many pages of color plates displaying the remarkable range of carved and engraved objects that Piette had collected from the caves of the Pyrenees.

Piette accumulated one of the most extensive collections in all of Europe of Upper Paleolithic sculpted and engraved figures made from bone, antler, and ivory through his excavations at Gourdan, Lortet, Arudy, Mas d’Azil and Brassempouy. He occasionally augmented his collection by purchasing objects from other sites. Sometime between 1898 and 1902, Piette acquired seven carved figurines originally discovered by Louis Julien in the Grimaldi cave, in Italy, in the 1880s. He also acquired objects excavated from the Paleolithic French sites of Laugerie-Basse and Les Eyzies-de-Tayac. Piette first raised the prospect of donating his collection to the Musée des Antiquités Nationales (Museum of National Antiquities) with Alexandre Bertrand, the founder and the original director of the Museum, in 1888. Several universities and foreign museums offered to purchase Piette’s collection but he reached an agreement with the museum in 1902 that resulted in the donation of the collection to the museum in 1904, under the condition that it would be kept together and be displayed according to his instructions, and that the museum pay for the publication of L’Art pendant l’Âge du Rennes. Salomon Reinach, who became director of the museum in 1902 following Bertrand’s death, designed the Salle Piette (Piette Hall) where the collection was displayed.

Despite publishing numerous scientific papers and presenting his ideas before various scientific institutions in France, Piette received little recognition or support from the French scientific community throughout his years of persistent research. Several prominent French scientists, particularly, Marcellin Boule, Émile Carthailac, and Salomon Reinach, eventually bemoaned the failure of French scientific institutions and the national government to recognize the value of Piette’s work. Indeed, it was only shortly before Piette’s death that his scientific peers recognized his achievements through official honors. It was partially through his friendship with the famous historian Henri Martin, who was a member of the Académie Française and a Senator in the French government, that Piette’s work began to gain the respect of French scientists. Piette was named a laureate of the Société Nationale des Antiquaires de France (National Society of Antiquaries of France), where he was awarded the Society’s gold medal in 1904. At the instigation of the prominent paleontologist Albert Gaudry, Piette was named a laureate of the Académie des Sciences (he was awarded the Saintour prize in 1905). And through the efforts of Salomon Reinach, he was named a laureate of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (he was awarded the Joest prize in 1905).

Piette had a direct influence on the career of the French prehistorian Henri Breuil. The two men met in 1897 when the young Henri Breuil was a student at the Seminary of Saint-Sulpice in Paris. Breuil joined the excavations at Brassempouy where he learned Piette’s stratigraphic excavation technique. Piette was impressed with Breuil’s skills as a draughtsman and asked him to draw some artifacts for his monograph. Breuil was also involved in arranging the Piette Hall at the Musée des Antiquités Nationales. Breuil later suggested that Piette’s collection of Magdalenian artifacts was an important influence in his decision in later years to study that archaeological period. Henri Breuil became an important prehistorian and expert on Paleolithic art during a career that spanned the first half of the twentieth century.

Piette was a member of many prominent scientific institutions in France and abroad. He became a member of the Société Géologique de France in 1851 and of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris in 1870. He was a member of the Société Historique de Haute-Picardie (serving as its president) and of the Association Française pour l’Avancement des Sciences. He was a non-resident member of the Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques. In recognition of his many scientific accomplishments, Piette was elected an honorary member of many regional, national, and foreign societies. He was also a corresponding member of many societies, notably the Société Nationale des Antiquaires de France (for a complete list see Fischer 1907). Piette was a founding member of the Société préhistorique de France (later renamed the Société préhistorique française), and he was elected its honorary president in 1904.

Piette died on 5 June 1906 in his family home, the château de la Cour des Prés, in Rumigny.

Selected Bibliography

De l’Éducation du peuple. Paris: A. Delahays, 1859.

Olry Terquem and Édouard Piette, Le Lias inférieur de l’est de la France, comprenant la Meurthe, la Moselle, le grand-duché de Luxembourg, la Belgique et la Meuse. Paris: F. Savy, 1865.

“Les grottes de Gourdan (Haute-Garonne).” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 6 (1871): 247-263.

“Sur la grotte de Gourdan, sur la lacune que plusieurs auteurs placent entre l’âge du renne et celui de la pierre polie, et sur l’art paléolithique dans ses rapports avec l’art gaulois.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 8 (1873): 384-425.

“La grotte de Lortet pendant l’âge du renne.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 9 (1874): 298-317.

“Sur de nouvelles fouilles dans la grotte de Gourdan.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 10 (1875): 279-296.

Edouard Piette and Julien Sacaze, “La Montagne d’Espiaup.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 12 (1877): 225-251.

Edouard Piette and Julien Sacaze, “Les tumulus d’Avezac-Prat, Hautes-Pyrénées.” Matériaux pour l’histoire primitive et naturelle de l’homme 10 (1879): 499-517.

“Note sur les tumulus de Bartrès et d’Ossun.” Matériaux pour l’histoire primitive et naturelle de l’homme 16 (1881a): 522-540.

Note sur l’épigraphie d’Élusa. Imprimerie Abadie, à Saint-Gaudens, 1881b.

“Exploration de quelques tumulus situés sur les territoires de Pontacq et de Lourdes.” Matériaux pour l’histoire primitive et naturelle de l’homme 1 (1884): 577- 594.

“Un groupe d’assises représentant l’époque de transition entre les temps quaternaires et les temps modernes.” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 108 (1889): 422-424.

Alcide d’ Orbigny and Édouard Piette, Paléontologie française: Description zoologique et géologique de tous les animaux mollusques et rayonnés fossiles de France, comprenant leur application à la reconnaissance des couches. Tome 3. Terrains jurassiques. Gastéropodes. Paris: Masson, 1891.

“Phases successives de là civilisation pendant l’âge du renne, dans le midi de la France et notamment sur la rive gauche de l’Arise (Grotte du M as dAzil).” Association française pour l’avancement des sciences part 2 (1892): 649-654.

“Races humaines de la période glyptique.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 5 (1894): 381-394.

“Note pour servir à l’histoire de l’art primitif.” L’Anthropologie 5 (1894): 129-146.

Edouard Piette and Joseph de Laporterie, “Les fouilles de Brassempouy en 1894.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 5 (1894): 633-648.

Edouard Piette and Joseph de Laporterie, “Sur des ivoires sculptés provenant de la station quaternaire de Brassempouy (Landes).” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 119 (1894): 249-251.

“Hiatus et lacune. Vestiges de la période de transition dans la grotte du Mas-d’Azil.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 6 (1895a): 235-267.

“Fouilles faites à Brassempony en 1895.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 6 (1895b): 659-663.

“La station de Brassempouy et les races humaines de la période glyptique.” L’Anthropologie 6 (1895c): 129-151.

“Études d’ethnographie préhistorique. Répartition stratigraphique des harpons dans les grottes des Pyrénées.” L’Anthropologie 6 (1895d): 276-292.

“Études d’ethnographie préhistorique, II. Les plantes cultivées de la période de transition au Mas d’Asil.” L’Anthropologie 7 (1896): 1-17.

“Études d’ethnographie préhistorique, III. Les galets coloriés du Mas d’Asil.” L’Anthropologie 7 (1896): 385-427.

Edouard Piette and Joseph de Laporterie, “Études d’ethnographie préhistorique, IV. Fouilles à Brassempouy en 1896.” L’Anthropologie 8 (1897): 165-173.

Edouard Piette and Joseph de Laporterie, “Études d’ethnographie préhistorique, V. Fouilles â Brassempouy en 1898.” L’Anthropologie 9 (1898): 531-555.

“Gravure du mas d’Azil et statuettes de Menton.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris 3 (1902): 771-779.

“Études d’ethnographie préhistorique, VI. Notions complémentaires sur l’Asylien.” L’Anthropologie 14 (1903): 641-654.

“Études d’ethnographie préhistorique, VII. Classification des sédiments formés dans les cavernes pendant l’âge du Renne.” L’Anthropologie 15 (1904): 129-176.

“Études d’ethnographie préhistorique, VIII. Les écritures de l’âge glyptique.” L’Anthropologie 16 (1905): 1-12.

“Études d’ethnographie préhistorique, IX. Le chevêtre et la semi-domestication des animaux aux temps plèistocènes.” L’Anthropologie 17 (1906): 27-54.

Édouard Piette and Jules Pilloy, L’art pendant l’age du renne. Paris: Masson, 1907.

Other Sources Cited

Ernest-Théodore Hamy, “Étude sur les ossements humains trouvés par M. Piette dans la grotte murée de Gourdan.” Revue d’anthropologie ser. 3, 4 (1889): 257-271.

Gabriel de Mortillet, “Essai d’une classification des cavernes et des stations sous abri, fondee sur les produits de l’industrie humaine.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des sciences 68 (1869): 553-555.

Gabriel de Mortillet, “Classification des diverses périodes de 1’age de la pierre.” Revue d’Anthropologie 1 (1872): 432-42.

Gabriel de Mortillet, Le préhistorique: antiquité de l’homme. Paris: C. Reinwald, 1883.

Secondary Sources:

Salomon Reinach, La collection Piette au Musée de Saint-Germain. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1902.

Henri Fischer, Edouard Piette 1827-1906. Rennes: Oberthur, 1906.

Marcellin Boule, “Edouard Piette.” L’Anthropologie 17 (1906): 214-224.

Émile Cartailhac, “Édouard Piette.” Revue des Études Anciennes 8 (1906): 274-276.

S. Zaborowski, “Edouard Piette,” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris 7 (1906): 260-264.

Adrien de Mortillet, [obituary of Edouard Piette]. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France 3 (1906): 225-233.

Paul Raymond, “Edouard Piette.” La Revue préhistorique (1906): 137-146.

Henri Breuil, “L’Évolution de l’art quaternaire et les travaux d’Edouard Piette.” Revue Archéologique ser. 4, 13 (1909): 378-411.

Henry Carnoy, “Piette (Louis-Edouard-Stanislas).” In Dictionnaire biographique international des écrivains. Vols. 1-4 1902-1906. Pp. 161-168. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1987 [Reprint].

Marthe Chollot-Legoux, Collection Piette, art mobilier préhistorique. Paris: Editions des Musées nationaux, 1964.

Henri Delporte, Piette, pionnier de la préhistoire. Paris: Picard, 1987.

Catherine Schwab, La collection Piette: Musée d’archéologie nationale, Château de Saint-Germain-en–Laye. Paris: Réunion des Musées nationaux; Saint-Germain-en-Laye; Musée d’archéologie nationale, 2008