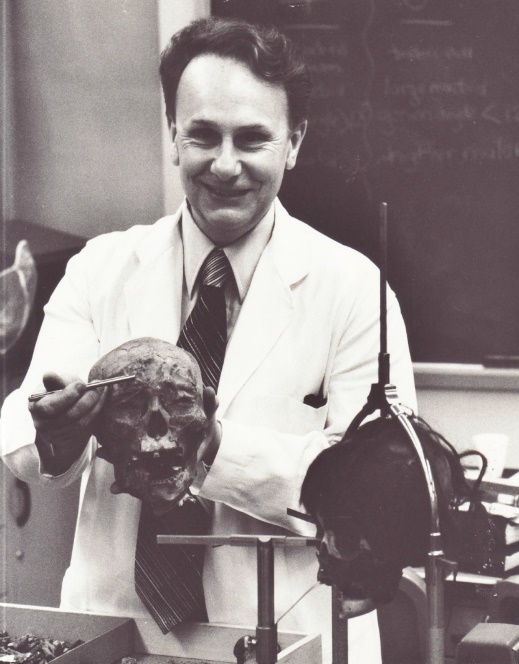

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy (1930–2014)

Matthew Goodrum

Kenneth Adrian Raine Kennedy was born in Oakland, California, on 26 June 1930. His father, Walter Burkhart Kennedy, worked as a bank officer, but he also pursued a love of music by performing as a pipe organist and choir director. Kennedy’s mother, Margaret Madge Kennedy, studied voice as a contralto. With such musical influences, Kennedy began piano lessons at age six and then studied the violin, which he continued to play well into his later years. These early experiences developed into a lifelong love of music, particularly opera and Indian ragas. The family moved to San Francisco in 1941 where they lived in the Marina district on land that had been dredged up from the sea for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exhibition. Kennedy developed an interest in “primitive man” while he was a student in grammar school and by the age of twelve he began reading books about anthropology, prehistory, and human paleontology. Following his graduation from Lowell High School in 1949, Kennedy enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley where he completed a bachelor’s degree in anthropology in 1953. He decided to stay at Berkeley for graduate school where he took courses with Theodore McCown, John Rowe, Robert Lowie, Frederica de Laguna, Sherwood Washburn and Robert Heiser. Kennedy obtained a master’s degree in anthropology in 1954 with a thesis titled “The Aboriginal Population of the Great Basin” that examined the cranial and postcranial morphology of Native American skeletons. It was later published in 1959 in the Reports of the University of California Archaeological Survey. Kennedy conducted this research under the supervision of physical anthropologist Theodore McCown, and this began a long relationship between the two men.

Because Kennedy had postponed being drafted into the United States military while he was in graduate school, he enlisted in the army and volunteered for the medical service after completing his master’s degree. He began his military service in late 1954, spending a year at the Walter Reed center just outside Washington, D.C., followed by two years at the Landstuhl Army Medical Center in Germany. Kennedy was discharged from the military in 1957, and he spent the next eight months traveling around Europe. In 1958, with funding from the GI Bill, he re-enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley to pursue a Ph.D., but he found major changes in the faculty of the Anthropology Department from when he had left four years earlier. Physical anthropologist Sherwood Washburn had just arrived from the University of Chicago, and the English archaeologist John Desmond Clark joined the faculty in 1961. Soon after returning to Berkeley, Kennedy received an invitation from Kenneth Oakley, geologist and paleoanthropologist at the British Museum (Natural History), to work on human fossil bones from Sri Lanka. Kennedy eagerly agreed to conduct his dissertation research on these South Asian specimens because so little research was being done in that region. Another factor influencing this decision was that his wife, Mary Marino, was a linguist interested in the Dravidian languages of India. Kennedy spent ten months at the British Museum in London studying nine Mesolithic human skeletons that had been excavated from the site of Bellan-bandi Palassa, in Sri Lanka, in 1956. Kennedy returned to Berkeley in 1961 and completed his Ph.D. under the supervision of Theodore McCown in 1962 with a dissertation titled “The Balangodese of Ceylon: Their Biological and Cultural Affinities with the Veddas.” This research was later published in the Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) (Kennedy 1965).

Kennedy spent the next two years in India on a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellowship at the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, located in Poona (now Pune). This was the beginning of collaborations with researchers in the Archaeology Department at the college that spanned many years. During this period, Kennedy published a paper on the fossil evidence for Pleistocene humans in India (Rajaguru and Kennedy 1963). He was also a member of the team that studied human skeletons unearthed at Lānghnaj, a village in the state of Gujarat, in India. Excavations between 1944 and 1963 had discovered animal fossils along with fourteen human skeletons from burials as well as large numbers of microlith tools dating to the late Mesolithic (these are now dated to 3,900 years ago, but they were originally thought to be much older). Kennedy and German paleontologist and archaeologist Gudrun Karve-Corvinus conducted excavations at Lānghnaj in November and December 1963 under the auspices of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, the University of Baroda, and the Government of Gujarat. These excavations produced additional animal bones, stone artifacts, and a new human skeleton (Karve-Corvinus and Kennedy 1964; Ehrhardt and Kennedy 1965). Kennedy also worked with Kailash Chandra Malhotra, a member of the Archaeology Department at Deccan College, to examine the Chalcolithic and Indo-Roman human skeletons excavated from the site of Nevasa, in India (Kennedy and Malhotra 1966).

Kennedy was hired as an assistant professor of physical anthropology at Cornell University in 1964 and he spent the rest of his career at Cornell teaching in the Departments of Anthropology, Asian Studies, and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at various times. Kennedy was particularly known for teaching a popular course from his Stimson Hall laboratory titled “Human Biology and Evolution.” He moved from the Anthropology Department to the Department of Ecology and Systematics (later renamed the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) in 1981. The circumstances of the move were painful because of his cherished identity as a physical anthropologist. Kennedy conducted pioneering work on the paleoanthropology and prehistory of South Asia ranging from the Miocene with the fossil anthropoid apes of the Siwalik Hills through the Middle Holocene with the Indus Valley Civilization. He also made significant contributions to skeletal biology and forensic anthropology, paleopathology, and he wrote on the history of evolution and biological anthropology.

Anthropological and paleoanthropological studies of prehistoric human skeletons was negligible in India until the 1980s, which made this region an excellent focus for Kennedy’s career. Decades after beginning this research, he addressed this apathy in an article that was intended to motivate archaeologists in South Asia to make the recovery of prehistoric human skeletons a greater part of their excavations (Kennedy 2003). While a professor at Cornell, Kennedy participated in projects and field research in Sri Lanka; at various sites in India in association with the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, the University of Allahabad, Vikram University, the Archaeological and Anthropological Survey of India, and the Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu State Departments of Archaeology and Museums; and at the University of Islamabad in Pakistan.

Beginning from the late 1960s, Kennedy studied human skeletal material from many different sites and different periods, and his research addressed a range of subjects. He examined human skeletons from the Mesolithic, Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Harappan, Iron Age, and Early Historic periods in order to collect paleodemographic information. This included studies of population displacement and mobility in the pre-Vedda and Vedda populations in Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon)(Kennedy 1969; 1972b). In The Physical Anthropology of the Megalith-Builders of South India and Sri Lanka (1975), Kennedy presented the results of his examination of 63 human skeletons dating to the Indian Iron Age (early first millennium BCE), a period associated with megalithic structures. Scholars previously thought the population of India during this period belonged to a single culture, but Kennedy showed that these peoples possessed a variety of physical characteristics and argued that they were not members of a single racial group. Furthermore, he observed no evidence of a sudden influx of biologically different peoples at the time of the Iron Age and the construction of megalithic structures, but that the peoples of modern India are biologically related to these Iron Age peoples. While Kennedy’s research dealt primarily with South Asia, he wrote two books at this time on broader subjects in physical anthropology, a book titled Neanderthal Man (1975) written for a general audience and Human Variation in Space and Time (1976).

In 1980, Kennedy published an article reviewing the existing ape and hominid fossil record of South Asia from the Miocene to the Holocene. Many of these fossils were only recently discovered and were little-known to most anthropologists. During the 1960s and 1970s, Elwyn Simons and David Pilbeam of Yale University collected Miocene ape fossils from South Asia, including the Ramapithecus fossils from the Siwalik Hills in Pakistan, which attracted great interest among paleoanthropologists. But this was also a time when ape and hominid fossil discoveries in East Africa were attracting the most attention from paleoanthropologists. Meanwhile, Kennedy engaged in several studies of human skeletons found at South Asian Mesolithic sites. From 1980 to 1981, Kennedy studied the 14 human skeletons that Govardhan Rai Sharma of the University of Allahabad excavated from the Mesolithic sites of Sarai Nahar Rai during excavations in 1972 and 1973 and the 26 human skeletons excavated from Mahadaha in 1978 and 1979 in the state of Uttar Pradesh, in India. At the time these were thought to be the oldest known Homo sapiens specimens from India, originally dated to 10,000 years ago, but they are now dated to approximately 2,800 to 4,000 years ago. Kennedy compared the morphology of the skeletons from the two sites and also compared them with Mesolithic skeletons from other parts of India and he concluded that during the Mesolithic there was a general trend toward reduced stature as well as other skeletal changes (Kennedy 1983; 1984; 1992a; Kennedy, , ). Kennedy was also a member of the team that studied the late Mesolithic human skeletons from Bagor and Tilwara, which were described in Bagor and Tilwara: Late Mesolithic Cultures of Northwest India (1982).

Kennedy was part of the team that studied Homo sapiens bones recovered from Batadomba lena and Beli lena Kitulgala caves in Sri Lanka during excavations conducted by Siran Deraniyagala of the Archaeological Survey Department of Sri Lanka between 1978 and 1983. The skeletal remains found in these caves consisted of 38 individuals and they ranged in date from 11,000 to 30,000 years ago. At the time, these were the most ancient specimens of anatomically modern Homo sapiens found in South Asia. They possessed robust skeletons and comparisons of these skeletons with other prehistoric human skeletons from South Asia supported the hypothesis that muscular-skeletal robusticity was a physical adaptation of early hunting-foraging populations. Kennedy and Deraniyagala observed a trend toward the reduction of sexual dimorphism and the development of a more gracile body form and smaller teeth that apparently accelerated as a result of the transition to agriculture and pastoralism and changes in the tools and practices used for food procurement and preparation. Kennedy conducted morphometric studies comparing these specimens with later prehistoric skeletons from South Asia to reach these conclusions (Kennedy et al. 1986; Kennedy et al. 1987; Kennedy and Deraniyagala 1989).

In 1982, Arun Sonakia of the Geological Survey of India excavated a fossil hominid calvaria in a Middle Pleistocene deposit (250,000 to 150,000 years ago) in the central Narmada valley of Madhya Pradesh, India. Researchers initially assigned this specimen to the new taxon of Homo erectus narmadensis. Kennedy was part of a team, along with Sonakia, that reexamined this fossil, and they concluded that the so-called “Narmada Man” should be classified as Homo sapiens or possibly Homo heidelbergensis. They noted that while the calvaria shared some anatomical features with Homo erectus specimens from Asia, it also exhibited a broad suite of morphological and mensural characteristics indicating similarities with early Homo sapiens fossils from Asia, Europe, and Africa (Kennedy and Chiment 1991; Kennedy et al. 1991). At this time, Kennedy also published a monograph on the human skeletons found in the Mesolithic site of Mahadaha held at the University of Allahabad (Kennedy 1992a) and on the large collection of human skeletons unearthed during excavations at the ancient city of Harappa between 1928 and 1988 (Kennedy 1992b). From his experience examining ancient human skeletons from India, Kennedy published a paper confronting the fraught anthropological and historical question over whether there was evidence of a distinct Aryan race that could be identified in the human remains from South Asia (Kennedy 1995b).

Siran Deraniyagala, from the Archaeological Survey Department of Sri Lanka, excavated human burials in 1968 and again in 1986 from Fa-Hien Lena, a large rockshelter in Sri Lanka. These excavations unearthed a sequence of human habitation deposits ranging from the Late Pleistocene to mid Holocene (approximately 38,000 to 5,400 years ago). Human bones were found in the oldest deposits, which dated to about 38,000 years ago. Kennedy and one of his graduate students, Joanne Zahorsky, studied these remains and concluded that they belonged to anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens). The oldest fragments of human bone came from several individuals (a young child, two older children, a juvenile, and two adults) and showed evidence of being secondary burials. This is a practice where corpses are exposed to the elements and after decomposition and predation by scavengers, the bones are placed in graves. The other human remains from Fa-Hien Lena included those of a young child dating to about 6,850 years ago and a young woman dating to about 5,400 years ago. Both were also secondary burials (Kennedy and Zahorsky 1997).

In 1999, Kennedy published an article titled “Paleoanthropology of South Asia.” This marks the first of several publications where Kennedy undertook a comprehensive review of the fossil evidence for early humans in South Asia. The article discussed the Miocene ape fossils collected in the Siwalik Hills in Pakistan and the efforts of paleoanthropologists to find possible evolutionary connections between these ancient apes and early hominids. Kennedy noted that while stone artifacts had been discovered from the Early Pleistocene, no human fossils had yet been recovered from this period. He described the South Asian skeletal record from the Middle and Late Pleistocene and addressed the question of how researchers had tried to identify prehistoric cultures on the basis of the stone artifacts studied by archaeologists, their geographical distribution, and the effort to relate these with extinct hominid species or prehistoric human populations. Kennedy criticized these approaches to South Asian paleoanthropology and rejected the traditional perspective of prehistoric South Asia as a region defined by major migrations of peoples from Western and Central Asia, which introduced new racial groups, new languages, and new cultural and technological innovations. Kennedy argued that archaeological and paleoanthropological research in the region should instead focus on studying the skeletal changes that occurred in human populations during the transition from a hunter-gather to an agricultural society. He encouraged the adoption of new research methods derived from the field of molecular anthropology, which used genetic techniques to investigate the relationships between ancient and modern South Asian populations. The paper also served to direct attention to South Asian paleoanthropology at a time when most researchers were focused on the dramatic fossil discoveries being made in Africa, China, and Europe.

Soon after this paper appeared, Kennedy published God-Apes and Fossil Men: Paleoanthropology of South Asia (2000), which became his most influential book. It presented a synthesis of modern research into the paleoanthropology of South Asia. Kennedy examined the prehistory of South Asia from the Paleolithic to the early historic period and offered a comprehensive summary of South Asian hominid fossils and prehistoric human skeletons. The book pioneered a new approach to investigating the paleoanthropology of South Asia that involved the integration of data from geology, archaeology, paleontology, ecology, human prehistory, primate and human paleontology, skeletal biology, human variation, genetics, and linguistics in order to understand South Asian populations belonging to distinct cultural periods that spanned the period from the Paleolithic to the Iron Age. Kennedy discussed the origins of agriculture, the emergence of an urban complex society during the period of the Harappan Civilization, the historical and anthropological search for the Aryans, research into the Iron Age Megalithic Builders of the region, and early historic populations. The significance of this book was quickly recognized, and Kennedy was awarded the W. W. Howells Medal, which is granted by the biological anthropology section of the American Anthropological Association, for the book.

The following year Kennedy published a paper that summarized the South Asian human skeletal and archaeological records spanning the Middle Pleistocene to the Middle Holocene. He compared these South Asian specimens with human fossils from this same period discovered in other parts of the world. The purpose of this paper was to situate the anthropological and archaeological developments in prehistoric South Asia in the broader context of the evolutionary and cultural developments that occurred elsewhere in the world, as well as exploring the continuities and developments that occurred within South Asia. While Kennedy had become a leading expert in the paleoanthropology of South Asia, he also contributed to the field of forensic anthropology. Several of his colleagues commented that Kennedy was one of the first academic anthropologists to make forensic anthropology a significant focus of his work rather than an occasional sideline. He engaged in forensic anthropology work over many years, analyzing local and regional cases in the northeast of the United States and serving as an expert witness in numerous criminal cases. Kennedy was one of the founding members of the American Board of Forensic Anthropologists (which is part of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences) and in 1978 he became one of the earliest certified holders of the Diplomate in Forensic Anthropology, which is conferred by the American Board of Forensic Anthropology.

After receiving the Diplomate accreditation, Kennedy became the primary consultant on forensic cases to the medical examiner for Tompkins County, in New York. He also participated in forensic cases and worked with law enforcement officials in other parts of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Kentucky. As Kennedy devoted less time to field research in South Asia in the early 1990s, he devoted more time to forensic cases and writing about forensic anthropology (Kennedy 1995a; 1996) while also continuing to write about the prehistoric peoples of South Asia. There were some connections between his South Asian anthropological research and his forensic work in the United States, notably his studies of the effects of occupational stress on the human skeleton (Kennedy 1998), which resulted in the book Atlas of Occupational Markers on Human Remains (1999) that he coauthored with Luigi Capasso and Cynthia Wilczak. In recognition of his work in forensic anthropology, Kennedy received the T. Dale Stewart Award for forensic anthropology from the American Academy of Forensic Sciences in 1987.

Perhaps Kennedy’s most famous demonstration of forensic science on the Cornell campus was his examination of the skeleton of an Egyptian mummy that had been donated to Cornell University in the 1880s. The inscription on the sarcophagus identified this individual as a court scribe named Penpi who lived during the Third Intermediate Period (c. 828 to 665 BCE). The mummy had been unwrapped and then put on exhibition on campus for many years and the mummy’s flesh was removed in the 1960s, leaving the disarticulated bones which were held in the Anthropology Collections at the university. Kennedy’s examination identified some possible disease indicators on the bones. In 1995, Kennedy published an influential article in the Journal of Forensic Sciences titled “But Professor, Why Teach Race Identification if Races Don’t Exist?” (Kennedy 1995a). In this paper he addressed a contentious issue in forensic as well as academic physical anthropology. While the typological race concept had been widely rejected by many biologists and anthropologists since the 1950s, the idea that humans could be classified into races (Black, White, Native American, etc.) still persisted in government census data as well as in the forensic sciences. Kennedy acknowledged that the determination of ancestry is a critical component of forensic anthropology’s methodology in the identification of human remains. He argued that in training forensics students, the paradox of the scientific rejection of the race concept and its survival in medical–legal contexts needed to be addressed explicitly. Kennedy suggested that forensic anthropologists and biological anthropologists are best able to determine the ancestral background of an individual when they are familiar with the geographical distribution and frequencies of phenotypic traits in modern human populations. Significantly, however, their methodology does not require a racial classification based upon nonconcordant characters in order to provide evidence for the positive identification of individuals.

In addition to his paleoanthropological and forensics research, Kennedy was also interested in the history of physical anthropology. He collaborated with his mentor Theodore McCown to edit Climbing Man’s Family Tree (1972), which was a compilation of major original texts pertaining to human evolution from 1699 to the mid-twentieth century. Kennedy’s last book, Histories of American Physical Anthropology in the Twentieth Century (2010), which he edited with Michael Little, contained papers addressing major themes in the history of American physical anthropology. The book arose from a symposium that Kennedy and Little organized to mark the 75th anniversary of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Kennedy was a member of many professional associations and institutions and held offices in a number of them. He was a member of the American Anthropological Association and served as the chairman of the biological anthropology section from 1986 to 1988. He was a member of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences and served as chairman of the physical anthropology section from 1994 to 1995. He was also a member of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists and served as its vice president from 1994 to 1996. Kennedy was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1992. He was an Episcopalian since childhood and was an Associate of the Order of the Holy Cross, an Anglican Benedictine monastic order. As such, he made regular retreats to the mother house of Holy Cross at West Park, New York. Kennedy was a communicant of St. John’s Church, in Ithaca, and served as a lay reader.

Throughout his career Kennedy made many field research trips to Sri Lanka, India, and Pakistan as well as visits to the British Museum in order to study their anthropological and archaeological collections of South Asian human skeletons and artifacts. In addition to this fieldwork and museum research, Kennedy had visiting academic appointments to institutions at California and Illinois in the United States. During these trips he was almost always accompanied by his second wife, Margaret Carrick Fairlie. She was a Juilliard-trained pianist and composer who also pursued research into the ethnomusicology of South Asia. During their stays in South Asia the couple filmed and recorded the music and dances of tribal populations in India and Pakistan and village dances in Sri Lanka. Kennedy retired from his faculty position at Cornell University in 2005 and was granted emeritus status. His former students organized a Festschrift symposium at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association in November 2008. Kenneth Kennedy died on 23 April 2014 in Ithaca, New York. His papers are held in the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at the Cornell University Library.

Selected Bibliography

S. N. Rajguru and Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, “Skeletal Evidence for Pleistocene Man in India,” Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute 24 (1963): 71–76.

G. Karve-Corvinus and Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, “Preliminary Report on Langhnaj: A Preliminary Report of the 1963 Archaeological Expedition to Langhnaj, Northern Gujarat.” Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute 24 (1964): 44–57.

“Human Skeletal Material from Ceylon, with an Analysis of the Island’s Prehistoric and Contemporary Populations.” Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Geology series 11, no. 4 (1965): 135–213.

Sophie Ehrhardt and Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, Excavations at Langhnaj: 1944–63, Pt. III: The Human Remains. Pune: Deccan College, Postgraduate and Research Institute, 1965.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and Kailash C. Malhotra, Human Skeletal Remains from Chalcolithic and Indo-Roman Levels from Nevasa: An Anthropometric and Comparative Analysis. Pune: Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, 1966.

“Paleodemography of India and Ceylon since 3000 B.C.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 31, no. 3 (1969): 315–319.

Thomas F. Lynch and Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, “Early Human Cultural and Skeletal Remains from Guitarrero Cave, Northern Peru.” Science 169, no. 3952 (1970): 1307–1309.

“Anatomical Description of Two Crania from Ruamgarh: An Ancient Site in Dhalbhum, Bihar.” Journal of the Indian Anthropological Society 7 (1972a): 129–141.

“The Physical Anthropology of Prehistoric South Asians.” The Anthropologist 17 (1972b): 1–13.

The Physical Anthropology of the Megalith-Builders of South India and Sri Lanka. Canberra: Faculty of Asian Studies in Association with Australian National University Press, 1975.

Neanderthal Man. Minneapolis, Minn.: Burgess, 1975.

Human Variation in Space and Time. Dubuque, Iowa: W. C. Brown Co., 1976.

“Fossil Man in India: The ‘Missing Link’ in Our Knowledge of Human Evolution in Asia.” Bulletin of the National Speleological Society 39, no. 4 (1977): 99–103.

Gregory L. Possehl and Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, “Hunter-Gatherer/Agriculturalist Exchange in Prehistory: An Indian Example.” Current Anthropology 20 (1979): 592–593.

“Prehistoric Skeletal Record of Man in South Asia.” Annual Review of Anthropology 9 (1980): 391–432.

John R. Lukacs, Virendra N. Misra, and Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, Bagor and Tilwara: Late Mesolithic Cultures of Northwest India, Part I, The Human Skeletal Remains. Pune: Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, 1982.

“Preliminary Report on the Mesolithic Human Remains from Sarai Nahar Rai, India: Their Skeletal Biology and Evolutionary Significance.” In History and Archaeology, ed. G. R. Sharma, Vol. 2 Allahabad: Allahabad University, 1983.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and Gregory L. Rossehl (eds.), Studies in the Archaeology and Palaeoanthropology of South Asia. New Delhi; Bombay; Calcutta: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co, 1984.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, John Chiment, Todd Disotell, and David Meyers, “Principal‐Components Analysis of Prehistoric South Asian Crania.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 64, no. 2 (1984): 105-118.

“Biological Adaptations and Affinities of Mesolithic South Asians.” In The People of South Asia: The Biological Anthropology of India, Pakistan, and Nepal, ed. J. R. Lukacs. Boston, MA: Springer US, 1984, 29–57.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and Peggy C. Caldwell, “South Asian Prehistoric Human Skeletal Remains and Burial Practices.” In The People of South Asia: The Biological Anthropology of India, Pakistan, and Nepal, ed. J. R. Lukacs. Boston, MA: Springer US, 1984, 159–197.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, , and “Mesolithic Human Remains from the Gangetic Plain: Sarai Nahar Rai.” Occasional Papers and Theses of the South Asia Program, Cornell University, 1986.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, T. , W. J. , J. , and J. “Biological Anthropology of Upper Pleistocene Hominids from Sri Lanka: Batadomba Lena and Beli Lena Caves.” Ancient Ceylon 6 (1986): 67–168.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, Siran U. Deraniyagala, William J. Roertgen, John Chiment, and Todd Disotell, “Upper Pleistocene Fossil Hominids from Sri Lanka.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 72, no. 4 (1987): 441–461.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and Mehmet Yaşar İşcan, eds., Reconstruction of Life from the Skeleton. New York: Liss, 1989.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and Siran U. Deraniyagala, “Fossil Remains of 28,000-Year-Old Hominids from Sri Lanka.” Current Anthropology 30, no. 3 (1989): 394–399.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, Arun Sonakia, John Chiment, and K. K. Verma, “Is the Narmada Hominid an Indian Homo erectus?” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 86, no. 4 (1991): 475–496.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and John Chiment, “The Fossil Hominid from the Narmada Valley, India: Homo erectus or Homo sapiens?” Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 10 (1991): 42–58.

Human Skeletal Remains from Mahadaha: A Gangetic Mesolithic Site. Ithaca, New York: South Asia Program, Cornell University, 1992a.

“Biological Anthropology of the Human Skeletons from Harappa: 1928–1988.” Eastern Anthropologist 45, no. 1–2 (1992b): 55–85.

“But Professor, Why Teach Race Identification if Races Don’t Exist?” Journal of Forensic Sciences 40, no. 5 (1995a): 797–800.

“Have Aryans Been Identified in the Prehistoric Skeletal Record from South Asia? Biological Anthropology and Concepts of Ancient Races.” The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia 1 (1995b): 32–66.

Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and J. L. Zahorsky, “Trends in Prehistoric Technology and Biological Adaptations: New Evidence from Pleistocene Deposits at Fa Hien Cave, Sri Lanka.” South Asian Archaeology, 2 (1995): 839–853.

“Markers of Occupational Stress: Conspectus and Prognosis of Research.” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 8, no. 5 (1998): 305–310.

“Paleoanthropology of South Asia.” Evolutionary Anthropology 8 (1999): 165–185.

Luigi Capasso; Kenneth A. R. Kennedy; Cynthia A Wilczac, Atlas of Occupational Markers on Human Remains. Chieti: Associazione antropologica abruzzese, 1999.

God-Apes and Fossil Men: Paleoanthropology of South Asia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2000.

“Middle and Late Pleistocene Hominids of South Asia.” In Humanity from African Naissance to Coming Millennia: Colloquia in Human Biology and Palaeoanthropology. Firenze: Firenze University Press, 2001, 167–174

“The Uninvited Skeleton at the Archaeological Table: The Crisis of Paleoanthropology in South Asia in the Twenty-first Century.” Asian Perspectives 42, no. 2 (2003): 352–367.

Secondary Sources

Michael A. Little, “Kenneth Adrian Raine Kennedy (1930–2014).” American Anthropologist 117, no. 1 (2015): 219–221.

Angela R. Lieverse and Nancy C. Lovell, “Obituary: Kenneth A. R. Kennedy (1930–2014).” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 161, no. 4 (2016): 569–570.

Angela R. Lieverse, “Foreword.” In Gwen Robbins Schug and Subhash R. Walimbe, eds., A Companion to South Asia in the Past. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2016, xx–xxv.

Subhash R. Walimbe, “Kenneth A. R. Kennedy—Pioneer of Human Skeletal Biology in India.” United Indian Anthropology Forum (2023).https://www.anthropologyindiaforum.org/post/kenneth-ar-kennedypioneer-of-human-skeletal-biology-in-india.

Frederic Gleach, “Kenneth Adrian Raine Kennedy.” Memorial Statements of the Cornell University Faculty, 2015.