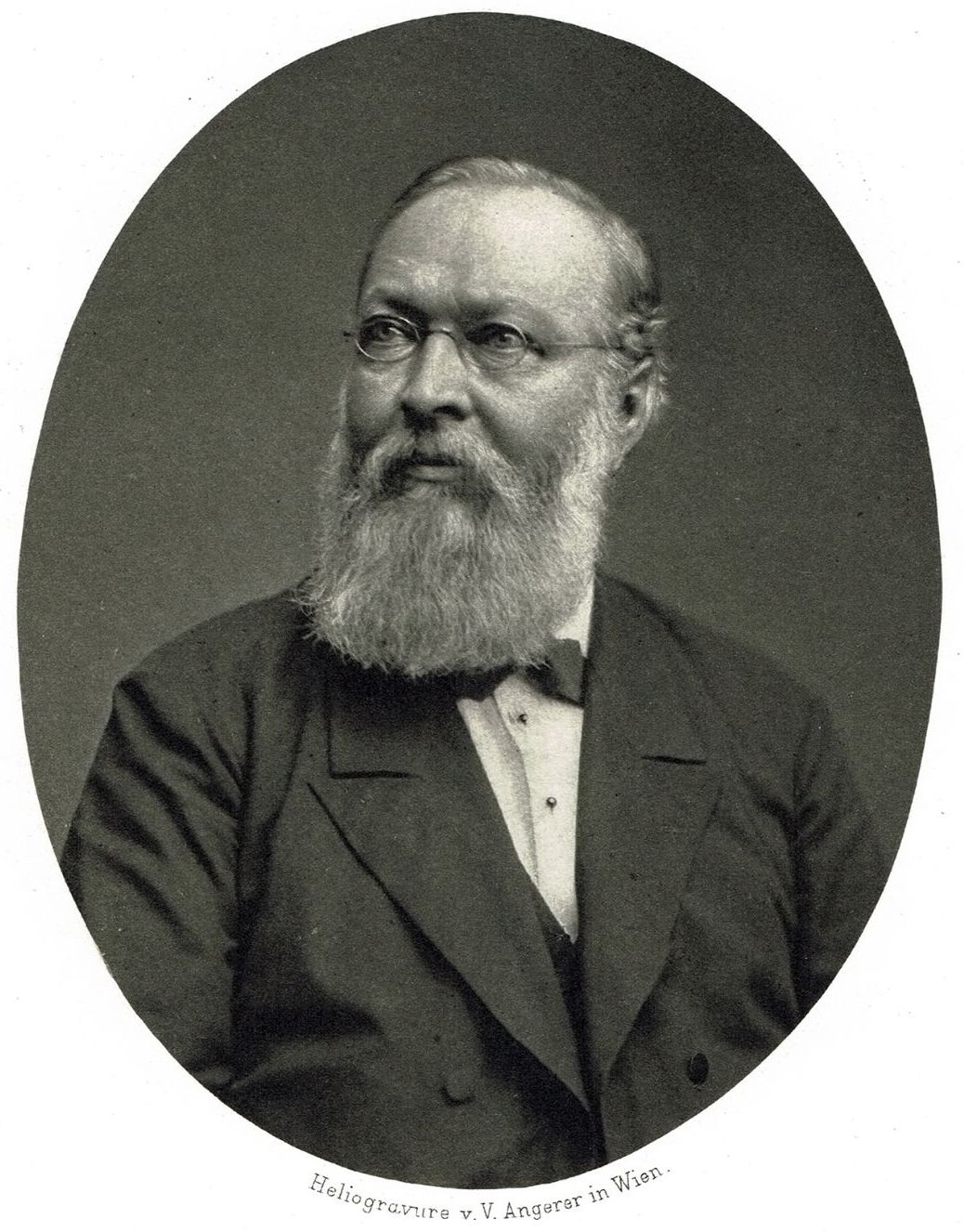

Josef Szombathy (1853–1943)

Matthew Goodrum

Josef Szombathy was born on 11 June 1853 in Vienna. His father, also named Josef, was a tailor whose family arrived in Vienna from Hungary, and his mother, Juliane Rubner, came from Bavaria. Szombathy’s father died in 1871, and from this point, Peter Trümmel, a clerk at the Landwirthschaftsgesellschaft (Agricultural Society), became his legal guardian. Szombathy attended the municipal secondary school (Oberrealschule) in Vienna and after graduating he studied chemistry at the Polytechnische Institut of Vienna from 1870 to 1874 (the institute changed its name to the Kaiserlich-Königlichen Technische Hochschule in 1872). At the Polytechnic Institute, he attended the lectures of Andreas Kornhuber on botany and paleontology as well as the lectures on mineralogy and geology taught by Ferdinand von Hochstetter. In 1872 Szombathy worked with Hochstetter on the preparation of an exhibit for the 1873 Weltausstellung (World Exhibition) in Vienna of giant birds from New Zealand sent by Julius Haast, the director of the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch. Szombathy was hired as Hochstetter’s assistant in 1875, and this relationship had a profound influence on Szombathy’s career. Hochstetter, who became a professor at the Polytechnische Institut in 1860, became interested in prehistory and anthropology after investigating the pile dwellings in Krain (Carniola, in what today is Slovenia) in 1864. He was an original member of the Anthropologische Gesellschaft in Wien (Anthropological Society in Vienna) from its founding in 1870. Hochstetter was appointed director of the Hofmineraliencabinet, the royal court mineral collection, in 1877, and Szombathy was appointed as his assistant at the Hofmineraliencabinett in September 1878. Meanwhile, Hochstetter was directed by the Austrian government to organize the new natural history museum in Vienna, the Kaiserlich-Königlichen Naturhistorisches Hofmuseum (later renamed the Naturhistorisches Museum), which was approved by emperor Franz Josef I on 29 April 1879. Construction of the museum was completed in 1881, and the museum opened in August 1889 with Hochstetter as the head of the Anthropological-Ethnological Department, which included the prehistoric collection.

During the summer of 1875, Szombathy accompanied Austrian geologist Franz Toula on a geological expedition to Bulgaria, which was still part of the Ottoman Empire at that time. In 1875 and 1876, Szombathy attended lectures at the University of Vienna on geology and paleontology taught by Eduard Suess as well as lectures on physical geography and the drawing of maps taught by Friedrich Simony. He also taught natural history at the Vienna municipal secondary school (Kommunal-Oberrealschule) from autumn 1875 through spring 1877, and he attended the paleontology lectures of Melchior Neumayr at the University of Vienna in 1880 and 1881. Szombathy’s first experience at an archaeological excavation came in May 1877 when he assisted Hochstetter during excavations of the Iron Age cemetery at Hallstatt, which produced many skeletons and artifacts. In 1879 Szombathy and Ferdinand Schulz, the preparator of the State Museum in Ljubljana, participated in the excavation of Križna jama (Kreuzberghöhle) in Krain (Carniola), which were also led by Hochstetter. These excavations resulted in the discovery of a complete cave bear skeleton. Szombathy used his training to make exact surveys and plans of the cave, sieved the sediments, and took samples for later examination, which was rather unusual for archaeological excavations in those days.

From 1879 to 1883, Szombathy explored, mapped, and excavated several Moravian caves on behalf of the Prähistorische Kommission (Prehistoric Commission). Ferdinand von Hochstetter had proposed the creation of a Prehistoric Commission within the Akademie der Wissenschaften (Academy of Sciences), and he served as the commission’s chairman after it was established in 1878. The Prehistoric Commission was created to undertake speleological investigations and “palaeo-ethnographical” research on Austrian territory. It was also tasked with preventing the unscientific exploitation of major sites for private purposes (see Mader 2018). Although Szombathy never became a member of the Prehistoric Commission, he participated in many excavations conducted under its auspices. As part of these investigations Szombathy examined the Diravica cave in 1880, where he discovered the remains of a prehistoric settlement from the Neolithic period. These included human artifacts made of stone and bones, bone remains from horses, pigs, deer, reindeer, and arctic hare. He also unearthed Pleistocene animals from the Výpustek Cave during excavations in 1880 and 1881. These included skeletons of cave bears (Ursus spelaeus), the skeleton of a rhinoceros (Rhinoceros tichorhinus), skulls and bones of a cave lion (Panthera spelaea), cave hyena (Crocuta spelaea), horse, wolf, wildcat, and ibex. These were sent to the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseums in Vienna.

Szombathy became director of the Prehistoric-Anthropological Collection at the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseums in 1882, when it was separated from the Ethnology Collection. He worked at the museum for the rest of his career and was appointed Kustos (Custodian) seventh class in 1886 and was promoted to Kustos first class in 1897. As the head of the Prehistoric-Anthropological Collection, Szombathy was influential both through his extensive excavations, which he undertook in order to increase the number of paleontological and prehistoric objects, and through his arrangement and cataloguing of the museum’s collections. After attaining his new position at the museum, Szombathy received a number of travel grants that allowed him to visit other museums and archaeological sites throughout Europe. He received a grant from the museum for a study trip to Germany and Denmark in July and August 1891. During this trip, he visited Prague, Teplitz, Dresden, Halle, Berlin, Danzig, Königsberg, Stettin, Stralsund, Copenhagen, Kiel, Hamburg, Hanover, Cologne, Mainz, Nuremberg, Regensburg, Munich, and Salzburg and was able to take part in the meeting of the Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie, und Urgeschichte (German Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory) in Danzig. In March 1893, Szombathy traveled with the Austrian writer and art collector Moriz Ritter von Gutmann to Egypt where he visited ancient monuments and the museum at Giza and acquired objects for the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseums. He returned home through Greece and visited ancient sites there including Eleusis, Corinth, Tiryns, Argos, Mycenae, and Olympia. Then in 1893, 1894, and 1896, he traveled on behalf of the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien to the region of Bukovina in the Eastern Carpathian Mountains (a region that today forms part of Romania and Ukraine) and visited museums in Chernivtsi, Lemberg, and Cracow. During these trips, lasting several weeks each, he collected objects for the ethnographic collection at the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseums as well as for the Verein für österreichische Volkskunde (Association for Austrian Folklore).

Szombathy conducted a large number of archaeological excavations over the course of his career. These ranged from Paleolithic sites dating to the Pleistocene through Bronze and Iron Age sites. His most significant contribution to paleoanthropology came during his excavations of the Fürst Johanns Höhle, a cave located near the town of Mladeč (Lautsch) in Moravia. Szombathy’s excavations, conducted under the auspices of the Academy of Sciences and the Naturhistorisches Hofmuseum, began in June 1881 and were continued during July and August 1882. The cave was owned by Prince Johann von und zu Liechtenstein, who offered some meager funds to support the excavations. Lack of money prevented a careful and systematic excavation of the cave’s deposits. While Szombathy did sketch the stratigraphy of the cave, he primarily focused on the recovery of objects. His main objective was to prove the contemporaneity of humans and reindeer in this region during the late Paleolithic. The excavations quickly produced Pleistocene animal fossils (reindeer, cave bear, mammoth) and stone and bone artifacts as well as fossilized human bones thought to belong to about five individuals. These consisted of two nearly complete crania and a partial juvenile cranium along with postcranial bones that were unearthed in 1881 and parts of a crania and some postcranial bones that were found in 1882 (see Antl-Weiser 2006). Szombathy was convinced by the evidence that these human bones dated from the Pleistocene (they were later determined to date from the Aurignacian period). These fossils were sent to the Naturhistorisches Hofmuseum. Szombathy presented a paper on the Mladeč fossils at the International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology held in Paris in 1900. He argued that the human remains were contemporary with the Paleolithic artifacts and the extinct animal bones found in the cave and that they resembled the Cro-Magnon fossils from France (Szombathy 1902a). Szombathy initially faced some skepticism regarding the Pleistocene age of the Mladeč specimens, in part because the specimens were fragmentary (a condition Szombathy rather implausibly attributed to cannibalism or some other form of human activity) and because they had been recovered very close to the surface of the cave deposits.

Szombathy conducted no further excavations at Mladeč, but the Moravian amateur prehistorian Jan Knies continued to excavate the cave and found more human bones. Jan Smyčka, a physician and mayor of the larger nearby town of Litau who worked with Knies during these excavations, sent a report of their discoveries to scientists in Vienna and Szombathy returned to Mladeč in August 1904 to inspect the new discoveries made by Knies and Smyčka in Quarry Cave. In 1903 Knies and Smyčka had unearthed the front half of a cranial vault and other cranial and skeletal fragments, and in 1904 they found a nearly complete adult calvaria, a fragmentary adult calvaria, and other cranial and skeletal fragments (Knies 1905). These fossils were again thought to date from the Aurignacian. Some of the fossils found by Knies went to the Litovel Museum and the rest went to the Moravské zemské muzeum in Brno. The Mladeč Caves became the property of the Krajinska musejni spolecnost v Litovli (Litovel Museum Association) in 1911, which initiated an extensive project of clearing the caves in order to make them accessible to the public. This work began in 1912 under Jan Smyčka’s supervision, but unfortunately it profoundly changed the Main Cave, whose chambers were completely cleared out to make it easier to move about in the cave. Szombathy later reported that some human remains were unearthed during this process. Additional human fossils were subsequently found by Josef Fürst and Smyčka around 1922, which prompted Szombathy to visit the site again in 1925 in order to inspect these new fossils. This led him to publish a detailed description of the geology, archaeology, and the human fossils recovered from the Mladeč caves (Szombathy 1925).

Szombathy investigated other caves as well, including the Pivka Jama-Höhle, in Krain (Carniola), which he explored and mapped in 1885. This work was organized by the Karst Committee of the newly founded Österreichischen Touristen-Club (Austrian Tourist Club). But many of his most important excavations were of Iron Age sites. In 1883 he dug for two months at Watsch (Vace), which was one of the richest Iron Age sites in Carniola. But his excavations of the burial grounds at St. Lucia (Sveta Lucija) and Idrija pri Bači were among his most important. Paolo Bizzarro had conducted excavations of the early Iron Age (Hallstatt period) burial grounds at St. Lucia (now Most na Soči, in Slovenia) in 1880 under the auspices of the Zentral-Kommission für Erforschung und Erhaltung der Kunst- und Historischen Denkmale (Central Commission for Research and Preservation of Art and Historic Monuments). Following these initial excavations, the Italian paleontologist Carlo Marchesetti, director of the Museum of Natural History in Trieste, excavated approximately 3610 individual graves between 1884 and 1902 (Marchesetti 1893). Szombathy conducted his own excavations of around 2450 graves between December 1885 and August 1890. Marchesetti and Szombathy were initially in competition with one another as they represented two institutions contending for finds, but by 1890 they began to collaborate in the work (see Mader 1995). Their excavations produced large quantities of pottery and iron artifacts (Szombathy 1887). From 1886 to 1887, Szombathy excavated the large necropolis containing several thousand cremation graves at Idrija pri Bači, located near the site of St. Lucia. These date to the Early Iron Age (Hallstatt period), Late Iron Age (La Tène period) and Roman periods. His excavations unearthed large numbers of grave goods consisting of bronze vessels and iron tools, some incised with north Italic inscriptions (Szombathy 1901). Szombathy conducted new excavations at Hallstatt in September 1886 which resulted in the discovery of thirteen graves in what is called the Steinbewahrersölde, and he excavated two Early Iron Age (Hallstatt period) barrows at Kučar in 1887 and 1888.

On various occasions throughout his career, Szombathy collaborated with the Slovenian archaeologist Jernej (Bartholomäus) Pečnik. Pečnik was a self-taught archaeologist from Dolenjska. His early excavations were carried out under the auspices of the regional museum in Ljubljana, but many of his excavations were supported by the Central Commission for Research and Preservation of Art and Historic Monuments. Szombathy first met him in 1886 and originally did not approve of his work, but after Dragotin Dežman’s death in 1889 Pečnik began collaborating with Szombathy and the museum in Vienna. Dragotin Dežman (known in German as Karl Deschmann) had served as the custodian of the Land Museum of Carniola in Ljubljana. During the course of their collaborations, Pečnik carefully followed Szombathy’s instructions for conducting excavations, including keeping the artifacts from each grave together and recording finds in a log. Szombathy and Pečnik excavated barrows in Slovenia beginning in 1887. In 1888 Szombathy opened ten barrows in Grm and another twenty in the Podzemelj necropolis; in 1888 he excavated thirty-seven Late Iron Age (La Tène period) graves in Zemelj. Szombathy also excavated the Bronze Age burial mounds in Kronporitschen south of Pilsen, first in 1888 and again intermittently from 1895 to 1909.

Jernej Pečnik excavated the Early Iron Age (Hallstatt period) site of Magdalenska gora (Magdalenenberg) in Slovenia during 1893 and 1894, which resulted in the discovery of human skeletons and numerous artifacts. These were examined and described by Szombathy (1894), and the artifacts were sent to the museum in Vienna. Construction work in the 1890s led to the discovery of a Late Roman period cemetery in Kranj (ancient Carnium), in Slovenia. When artifacts and human bones were unearthed, Pečnik initiated excavations in June 1900 that unearthed three graves. This led Szombathy and Pečnik to dig there in June and July 1901 and together they opened sixty-six graves (Szombathy 1902b). Szombathy also worked extensively at the prehistoric cemetery of Gemeinlebarn, which contained nearly 300 graves belonging to several cultures. These prehistoric graves first came to light during construction work near the Gemeinlebarn train station, which prompted the Austrian amateur archaeologist Adalbert Dungel to investigate some cremation burials in 1885 with the assistance of the Prehistoric Commission. In November 1885, the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseum began excavations at Gemeinlebarn, but it was not until 1889 that Szombathy began excavating a series of Early Bronze Age cremations, Middle Bronze Age burials, and Early Iron Age (Hallstatt period) tombs (Dungel and Szombathy 1890). He led more extensive excavations at the site from 1916 to 1922 despite the difficult conditions during the First World War. Szombathy unearthed many artifacts and a large number of skeletons at Gemeinlebarn, and he published an account of these discoveries in Prähistorische Flachgräber bei Gemeinlebarn in Niederösterreich [Prehistoric Flat Graves near Gemeinlebarn in Lower Austria] (1929).

Szombathy’s most significant contribution to Paleolithic archaeology was the discovery of the famous Venus of Willendorf figurine (see Antl-Weiser 2008). In 1908 railroad construction cut through the loess deposits near the village of Willendorf, in Lower Austria, revealing seven Paleolithic layers. Szombathy, along with German prehistorian Hugo Obermaier and Josef Bayer, who worked at the museum in Willendorf, saw this as an opportunity to explore the cultural development of the Upper Paleolithic in the region. Obermaier had recently completed his dissertation on Central European Paleolithic archaeology and had worked with Szombathy for several years already. Obermaier and Bayer managed the excavations, which were conducted under the auspices of the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseum. They unearthed numerous Aurignacian stone tools; then on 7 August 1908 all three were present when one of the excavators, Johann Veran, found the Venus figurine. The statuette was carved from a type of oolitic limestone that is not found in the region, and so it must have been brought there. The Venus of Willendorf was the best-preserved Paleolithic figurine that had been discovered at the time (Szombathy 1909; 1910). When first discovered the statuette was thought to be approximately 15,000 years old, but it is now thought to date to about 25,000 years ago. Szombathy presented a plaster replica of the figurine at a conference in 1909 and compared it to the Brassempouy statuette discovered by French Paleolithic archaeologist Édouard Piette.

During the course of his long career as the head of the Prehistoric-Anthropological Collection at the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseum, Szombathy dramatically expanded the number of artifacts in the collection, from about 7000 objects to about 53,000, and the anthropological collection increased from about 600 to more than 700 specimens. He also created inventories of the finds in the collection and introduced the practice of listing finds chronologically instead of by region, which was the more common practice at the time. As a field archaeologist, Szombathy introduced rigorous excavation and recording methods. He increased the scientific quality of his excavations by utilizing his early technical and scientific training, and his research displayed a commitment to positivism. This contrasts with the following generation, which approached prehistoric archaeology from a humanities perspective. Szombathy published numerous papers on his archaeological discoveries, but many of his excavations were never published, which makes his extensive excavation diaries and reports important sources of information for scholars today. In addition to his work as a prehistoric archaeologist, Szombathy also conducted anthropological investigations of the prehistoric skeletons he unearthed, including craniological studies of the skulls from Hallstatt, and he developed new osteological measurement methods in the course of this research.

Szombathy was an active member of many scientific institutions. He was an influential member of the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien (Anthropological Society in Vienna). He was elected a member in November 1879, served as the Society’s secretary, and from 1910 to 1920 he was its vice president. In recognition of his many achievements Szombathy was named an honorary member of the Society in March 1931. Szombathy was a member of the Wiener Prähistorische Gesellschaft (Vienna Prehistoric Society) from its founding in 1913 and served as its vice president from 1913 to 1934. He was named an honorary member of the Society in February 1933, and he was honorary president of the Society from 1935 until his death in 1943. Szombathy was an important member of the Österreichischen Touristen-Club (Austrian Tourist Club) and served as its president from 1896 to 1898 and again from 1906 to 1912. Franz von Hauer, the director of the Geologischen Reichsanstalt, created the Section for Speleology (Sektion für Höhlenkunde) within the Club in 1879 in order to encourage cave exploration. In 1885, members of the Section for Speleology, which included Szombathy, formed the Karst Committee of the Club. Over the years Szombathy led Club trips to Bosnia in 1897, to Dalmatia in 1898, and to Athens, Constantinople, Santorin, Egypt, Malta and Sicily in 1905. In 1883 Szombathy became a member of the Verein zur Verbreitung naturwissenschaftlicher Kenntnisse in Wien (Association for the Dissemination of Scientific Knowledge in Vienna), which had been created in 1860. He was also a member of the Wissenschaftlichen Club in Wien (Scientific Club in Vienna) from 1889 until it was dissolved in 1927, but he had been associated with the club from its origin. The Club was founded by Ferdinand von Hochstetter in 1876 with the purpose of promoting social and intellectual interactions among the members of the various scientific institutions in Vienna.

Szombathy was appointed Konservator (curator) of the Zentral Kommission für die Erforschung und Erhaltung der Kunst- und historische Denkmale (Central Commission for the Research and Preservation of the Art and Historical Monuments) for the districts of Baden, Neunkirchen, and Wiener Neustadt in 1900. He had previously worked as a Korrespondent for the commission. In this post as well as his other positions, he was able to coordinate the scientific and financial collaboration between the Central Commission, the Prehistoric Commission, the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseum, and the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft. In 1905 he was appointed secretary of a committee to establish regulations for the preservation of antiquities. In fact, Szombathy had first expressed the need for a law to preserve prehistoric monuments and sites in 1889 at a joint meeting of the Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie, und Urgeschichte and the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien, but it was only in 1909 that the Central Commission began to draft such a law.

His international stature is reflected in the many foreign scientific institutions of which he was a corresponding member. These include the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Philadelphia (1884), the American Philosophical Society (1885), the Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte in Berlin (1894), the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (1901), the Kongelige Nordiske Oldskrift-Selskab in Copenhagen (1907), the Ecole d’Anthropologie in Paris (1908), the Vereins für das Museum schlesischer Altertümer in Breslau, the Altertumsgesellschaft “Prussia” in Königsberg, the Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts in Wien, and the Hrvatsko Arheologicko Druztvo in Agram. Szombathy was also elected an honorary member of the Munich branch of the Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie, und Urgeschichte in 1895, and of the Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte in 1918.

Szombathy served as co-editor of the Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien on several occasions (1883-86, 1894-1901, 1910-20). Although he never became a member of the Prehistoric Commission of the Academy of Sciences, Szombathy did serve as the anonymous editor of the Commission’s Mitteilungen. After World War I, he was named chairman of the Studienfürsorge für Kriegerwaisen (Student Welfare Service for War Orphans). In March 1918 Szombathy was appointed curator (Konservator) of the Kaiserlich-Königlichen Staatsdenkmalamtes für prähistorische und antike Agenden (State Monument Office for Prehistoric and Ancient Agendas) for the districts of Baden, Lilienfeld, and Mödling.

Throughout his career, Szombathy attended many meetings of the Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie, und Urgeschichte as well as other scientific meetings throughout Germany and the Austrian Empire. He attended the Congrès international d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques in Paris in 1900, where he presented a paper on the human fossils from Mladeč. While in Paris, he visited the archaeological collections at the Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, and at the Louvre. He also took the opportunity to visit the Paleolithic sites of the Vézère valley. On yet another occasion, in the spring of 1924, he traveled through Italy visiting Venice, Florence, Naples, Pompeii, Palermo, Rome, and Bologna where he devoted much of his attention to their archaeological and art objects. Szombathy received several honors in the course of his career. He was made a Ritter des Franz Joseph-Ordens (Knight of the Franz Joseph Order) in 1889 in recognition for his efforts in creating the prehistoric collection at the Museum, and a Ritter des Ordens der Eisernen Krone 3rd Klasse (Knight of the Order of the Iron Crown 3rd Class) in 1916 at the time of his retirement. He was awarded a Medal of Honor (Ehrenmedaille) in 1914 for forty years of service. He was also appointed government councilor (Regierungsrat) on 21 December1905.

After many years as director of the Prehistoric-Anthropological Collection at the Naturhistorisches Hofsmuseum, Szombathy took early retirement in 1916 due to a legal dispute relating to excavations conducted in 1910 by Pietro Savini, which involved claims of the embezzlement of finds. However, Szombathy continued to act as a “honorierte wissenschaftliche Hilfskraft” (honored research assistant) at the museum until January 1919 when Josef Bayer returned from military service in the Middle East during World War I and became director of the Prehistoric-Anthropological Collection. Bayer had previously served as Szombathy’s assistant at the museum. Even after his retirement Szombathy continued to conduct excavations for the museum until 1929, and he remained an unpaid volunteer at the museum. The museum honored Szombathy with the title of Hofrat after he retired. In June 1933, Sombathy was honored on the occasion of his 80th birthday during a joint meeting of the Anthropologische Gesellschaft in Wien and the Wiener Prähistorische Gesellschaft. Sombathy’s first wife, Sophie Salomon, died of a stroke on 3 November 1925. They had been married since 2 October 1882. Szombathy married his second wife, Wilhelmine Theresia Rent, in 1933. Szombathy died of cardiac arrest on 9 November 1943 at his home in Vienna.

Selected Bibliography

“Die Skelette aus den Gräbern von Roje bei Moräntsch in Krain.” Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Mathematisch- Wissenschaften Classe) 42 (1880): 45-54.

“Über Ausgrabungen in den mährischen Höhlen im Jahre 1881.” Sitzungsberichte der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe) 85 (1882): 90-107.

“Die Höhlen und ihre Erforschung.” Schriften des Vereins zur Verbreitung naturwissenschaftlicher Kenntnisse Wien 23 (1883): 487-526.

“Grabfunde von Kunewald in Mähren.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 14 (1884): 59-60.

“Ausgrabungen in den mährischen Höhlen im Jahre 1883.” Sitzungsberichte der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe) 89 (1884): 353-358.

“Eine paläolithische Fundstätte im Löss bei Willendorf in Niederösterreich.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 14 (1884): 35-36.

“Die Nekropole von Santa Lucia im Küstenlande.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 17 (1887): 26-29.

“Ausgrabungen am Salzberg bei Hallstatt 1886.” Mitteilungen der Prähistorischen Kommission der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1 (1888): 1-7, 49-79.

Adalbert Dungel and Josef Szombathy, “Die Tumuli von Gemeinlebarn.” Mittheilungen der prähistorischen Commission der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien 1 (1890): 49-77.

“Funde aus dem Löss bei Brünn.” Correspondenzblatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie, und Urgeschichte 20 (1889), 85-88

“La Tène-Fund von Mitrowitz an der Save in Slavonien.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 20 (1890): 10-19.

“Ein Tumulus bei Langenlebarn in Niederösterreich.” Mitteilungen der Prähistorischen Kommission der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1 (1893): 79-90.

“Neue figural verzierte Gürtelbleche aus Krain.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 24 (1894): 226-231.

“Bemerkungen zu den diluvialen Säugethierknochen aus der Umgebung von Brünn.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 29 (1899): 78-84.

“Der zwölfte internationale Congress für prähistorische Anthropologie und Archäologie zu Paris 1900.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 30 (1900): 189-197.

“Das Grabfeld zu Idria bei Bača.” Mittheilungen der prähistorischen Commission der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien 1 (1901): 291-363.

“Un crâne de la race de Cro-Magnon trouvé en Moravie.” Compte rendu Congrès international d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques [1900] (1902a): 133-140.

“Grabfunde der Völkerwanderungszeit vom Saveufer bei Krainburg.” Mittheilungen der k.k. Central-Commission für Erforschung und Erhaltung der Kunst- und Historischen Denkmale 3. Vol. 1 (1902b): 231.

“Die Vorläufer des Menschen.” Schriften des Vereins zur Verbreitung naturwissenschaftlicher Kenntnisse Wien 43(1903): 1-35.

“Der diluviale Mensch in Europa.” Globus 84 (1903): 319-324.

“Die Vorläufer des Menschen.” Schriften des Vereins zur Verbreitung naturwissenschaftlicher Kenntnisse Wien 43 (1903): 1-35.

[The Forerunners of Man]

“Neue diluviale Funde von Lautsch in Mähren.” Jahrbuch der k. k. Zentral-Kommission für Kunst-und historische Denkmäler 2 (1904): 8-15.

“Die Aurignacienschichten in Löss von Willendorf,” Korrespondenzblatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie, und Urgeschichte 40 (1909), 85-88.

“Die diluvialen Kulturschichten von Willendorf. Vortrag auf der Monatsversammlung am 12. Januar 1910 vor der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 40 (1910): 8-9.

“Nachbildung des diluvialen Schädels von La Chapelle-aux-Saints.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 43 (1913): 22-24.

“Altertumsfunde aus Höhlen bei St. Kanzian im österreichischen Küstenlande.” Mittheilungen der prähistorischen Commission der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien 2 (1913): 127-190.

“Das Versiegen einzelner prähistorischer Kunstepochen und die Stellung der paläolithischen Kunst Mitteleuropas.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 45 (1915): 141-161.

Tabellen zur Umrechnung der Schädelmasse auf einen Rauminhalt von 1000 Kubitkzentimetern. (Ergänzungsheft zu den Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien). Vienna: Kommission bei Alfred Hölder, 1918.

“Ausgrabungen in Gemeinlebarn (N.-Ö.) im Jahre 1919.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 50 (1920): 58–60.

“Die jungdiluvialen Skelette von Obercassel bei Bonn.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 50 (1920): 60-65.

“Die Tumuli im Feichtenboden bei Fischau am Steinfeld.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 54 (1924): 164-197.

“Die diluvialen Menschenreste aus der Fürst-Johanns-Höhle bei Lautsch in Mähren.” Die Eiszeit 2 (1925): 1–34, 73–95.

“Gegen die Überschätzung des Homo Aurignacensis Hauseri, Klaatsch.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 57 (1927): 28-38.

“Die Menschenrassen im oberen Paläolithikum, insbesondere die Brüx-Rasse.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 57 (1927): 106–110.

“Die Menschenrassen im oberen Paläolithikum: Bemerkungen zu Dr. K. Sallers Abhandlung.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 57 (1927): 202–219

Prähistorische Flachgräber bei Gemeinlebarn in Niederösterreich. Berlin and Leipzig: W. de Gruyter, 1929.

“Kleinwüchsige Skelette aus bronzezeitlichen Gräbern bei Gemeinlebarn.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 61 (1931): 1-28.

“Bronzezeit-skelette aus Niederösterreich und Mähren.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft Wien 64 (1934): 1-101.

Other Sources

Jan Knies, “Nový nález diluviálního člověka u Mladče na Moravě.” Věstník klubu přírovědeckého Prostějov 8 (1905): 3-19.

Carlo de Marchesetti, Scavi nella necropoli di S. Lucia presso Tolmino. (Bollettino della Società Adriatica di Scienze Naturali in Trieste 15). Trieste, 1893.

Secondary Sources

Carl Blaha, Johann Jungwirth, and Karl Kromer. “Geschichte der Anthropologischen und der Prähistorischen Abteilung des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien.” Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien 69 (1965): 451-461.

Stane Gabrovec, “Josef Szombathy: Prispevek k zgodovini konservatorske službe na slovenskih tleh.” Varstvo spomenikov 12 (1967): 63-67.

Brigitta Mader, “Die Zusammenarbeit der Naturhistorischen Museen in Wien und Triest im Lichte des Briefwechsels von Josef Szombathy und Carlo de Marchesetti (1885 -1920): ‘Mit besten Grüßen von Haus zu Haus’.” Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien. Serie A für Mineralogie und Petrographie, Geologie und Paläontologie, Anthropologie und Prähistorie 97 (1995): 145-166.

Angelika Heinrich, “Josef Szombathy (1853-1943).” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 133 (2003): 1–45.

Walpruga Antl-Weiser, “Szombathy’s excavations in the Mladecˇ Cave and the first presentations of the results”. In Maria Teschler-Nicola, Early Modern Humans at the Moravian Gate: The Mladecˇ Caves and their Remains. Pp. 1-16. Vienna/New York: Springer-Verlag, 2006.

Walpurga Antl-Weiser, Die Frau von W. Die Venus von Willendorf, ihre Zeit und die Geschichte(n) um ihre Auffindung. (Veröffentlichungen der Prähistorischen Abteilung; Vol. 1). Vienna: Verlag der Naturhistorischen Museums, 2008.

Brigitta Mader, Die Prähistorische Kommission der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1878-1918. Vienna: Verlag der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2018.