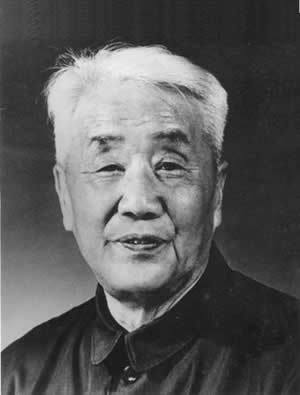

Jia Lanpo (1908–2001)

Matthew Goodrum

Jia Lanpo (贾兰坡) (in early publications his name was transliterated as Chia Lan-p’o) was born in Yutian, Hebei Province, in China on 25 November 1908 during the waning years of the Qing dynasty. He graduated from the Huiwen Academy in Beijing in 1929, and later that year, he obtained a position as a trainee at the newly established Cenozoic Research Laboratory, located at the Peking Union Medical College in Beijing. Canadian anatomist Davidson Black and Chinese geologist Weng Wenhao created the Laboratory as a result of Black’s discovery of hominid fossils at Zhoukoudian, near Beijing, and it rapidly became an important center of paleoanthropological research. In 1931 Jia became a technical assistant at the Geological Survey of China and joined the excavations at Zhoukoudian working under the guidance of Chinese paleontologist Pei Wenzhong, who supervised the excavations. As a member of the team excavating at Zhoukoudian, Jia worked first with Davidson Black, who led the paleoanthropological research at Zhoukoudian and served as director of the Cenozoic Research Laboratory until his death in 1934, and then with the German anatomist Franz Weidenreich, who was appointed director of the Laboratory after Black’s death. A number of foreign researchers also spent time at the Laboratory and at Zhoukoudian during these years, including Swedish paleontologist Anders Birger Bohlin, French paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and the French prehistorian Henri Breiul.

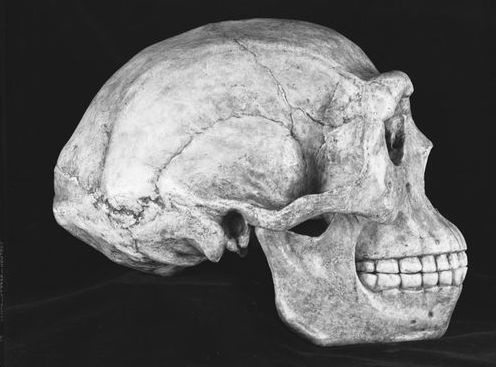

Jia served as personal secretary to the Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and had the opportunity to work with Henri Breuil while these men were in Beijing. These interactions with foreign scientists fostered Jia’s lifelong desire to maintain international links with scientists. When Pei traveled to France in 1935 to study with Henri Breuil, Jia was appointed field director of excavations at Zhoukoudian, and in November 1936, he oversaw the discovery of three nearly complete Homo erectus crania, along with stone artifacts and animal fossils. Jia was promoted to Research Investigator in 1937, but work at Zhoukoudian came to an end in 1941 as the Japanese army advanced on Beijing. Pei and Jia helped Weidenreich photograph and make plaster casts of the Homo erectus fossils and packed the fossils so they could be sent out of the country, but unfortunately the crates carrying the fossils were lost in transit. After Weidenreich left China in 1941, because of the Japanese invasion, Pei Wenzhong became the director of the Cenozoic Research Laboratory. Jia was promoted to Research Technician in 1945 and is credited with preserving thousands of research notes, letters, and 2000 photographs and negatives from the excavations at Zhoukoudian by hiding them in his own home in Beijing during the war.

After the victory of the communists and the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Cenozoic Research Laboratory was reorganized, and in 1953 it was renamed the Laboratory of Vertebrate Paleontology (古脊椎动物研究室) and was affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In 1960 the Laboratory was renamed the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (古脊椎动物与古人类研究所), and it has become one of the leading scientific institutions in China. Jia was one of the scientists, along with Pei Wenzhong, who were instrumental in the creation of the IVPP. During this period of transition and institution building, Jia was successively promoted to the positions of Assistant Research Professor (1949-1953), Associate Research Professor (1953-55), eventually becoming a Research Professor in 1956 at the IVPP. During his career at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Jia held a number of posts, including Assistant Director of the Institute’s Cenozoic Laboratory, Director of its Specimen Preparation Laboratory, and Head of the Zhoukoudian Work Station. It was also probably important for his career that in 1950 Jia joined the Jiusan Society (九三学社), one of the eight legally recognized political parties in the People’s Republic of China that follow the direction of the Communist Party of China and are members of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

Jia led the excavations at Zhoukoudian when they resumed in 1949, and his research focused on the changes in the animal fossils over time at the site. This led him to conclude that northern China had undergone a series of climactic changes, consisting of alternating warm and cold periods, during the several hundred thousand years that the area was occupied by hominids. Jia wrote several books during the 1950s and 1960s, describing Homo erectus in China, their culture, and the world they inhabited. Among the most prominent was 中國猿人 (北京人) [Chinese Ape Man (Peking Man)], first published in 1950. Jia was part of a team conducting a geological survey in the southeastern Chinese Autonomous Region of Guangxi in 1956 that made a rare discovery of Gigantopithecus teeth at a site called Heidong (Black Cave). He excavated Paleolithic sites at Dingcun in 1954 and at Kehe in 1959, both located in Shanxi Province in northern China. During excavations in 1957 in Changyang County, Hubei Province, Jia’s team unearthed a human maxillary (upper jaw) bone from deposits containing animal fossils dating from the Middle Pleistocene, making them as much at two hundred thousand years old (Jia 1957). Jia argued that the fossil belonged to early Homo sapiens, but this conflicted with the prevailing theories about the origins of Homo sapiens in Asia accepted by European and American anthropologists. In contrast, Jia long supported the view that modern humans had evolved in central Asia from earlier hominid species such as Homo erectus, and he rejected the Out of Africa Hypothesis, which argues that Homo sapiens evolved in Africa and then migrated into Europe and Asia. In his book Early Man in China, published in English in 1980, Jia argued that hominids had evolved in China over long periods of geologic time independently of hominids that were evolving in Africa. He presented Homo erectus (Peking Man) as an important part of Chinese history, and he traces the pedigree of modern Chinese peoples back into the Pleistocene in China.

In 1964 he was part of the multidisciplinary team that investigated the geologic deposits at Lantian, in Shaanxi Province, where a Homo erectus mandible and partial cranium were found. His subsequent excavation of the Early Paleolithic site at Xihoudu and the Late Paleolithic site at Shiyu in Shanxi Province in the 1960s provided important insights into the human occupation of China in the Pleistocene. On the basis of his studies of Paleolithic artifacts from across Northern China, Jia and his colleagues proposed the idea that there were two parallel stone tool traditions in Northern China. The Kehe-Dingcun Series is characterized by large choppers and triangular points, while the Zhoukoudian Locality 1-Shiyu Series is characterized by small flake tools. They suggested that these two stone tool traditions persisted from the Early Paleolithic until the Late Paleolithic, extending even into the Neolithic when they developed into two different agricultural patterns (Jia, Gai, and You 1972). This hypothesis influenced Chinese archaeologists for several decades.

Jia led the excavations at Xujiayao, also in Shanxi Province, during 1976, 1977, and 1979 that unearthed a large quantity of stone tools along with bones of early Homo sapiens from several individuals including the partial cranium of a child (Jia et al. 1979). In 1975 Jia published The Cave Home of Peking Man, an English language book that discussed Homo erectus in China, the archaeological evidence of their culture, the environment in which they lived, and their geologic age. Other works discussed the faunal and climactic changes that occurred in northern China during the Pleistocene. Notably, Jia suggested that the Homo erectus remains from Zhoukoudian did not represent the earliest stages of human evolution in China. He suspected the earliest evidence of humans in China might be discovered in the early Pleistocene deposits of the Nihewan basin in Hebei province. Chinese researchers conducted excavations in the Nihewan basin during the 1970s, but Jia was later instrumental in arranging a rare Chinese and American collaboration, led by himself and John Desmond Clark of the University of California at Berkeley, that worked in the Nihewan basin from the late 1980s through the early 1990s. Throughout much of his career, Jia pursued a multidisciplinary approach to investigating paleoanthropology, and this multidisciplinary approach was reflected in much of the research conducted at the IVPP.

During the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, when universities were closed and intellectuals became targets of abuse, Jia and other researchers at the IVPP were harassed and the institution vandalized. Despite years of political and social turmoil spanning the Japanese invasion of China through the communist revolution and the Cultural Revolution, Jia remained a prominent advocate of scientific research in China. During his long and influential career, Jia held many professional positions in prominent Chinese scientific institutions. He was elected Academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1980, and he served as a member of the Cultural Bureau of the Chinese State Council. He was a member of the Institute of Archaeology (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and was a member of the Geological Bureau of the Biological Section of the Chinese Academy of Natural Sciences. He served as the Assistant Director of the Quaternary Geology and Glaciology Sections of the Chinese Geological Association. He also served as the Assistant Chairperson of the Board of Directors of the Chinese Archaeological Association as well as the Assistant Director and Secretary of the Chinese Pacific History Society. He was also a member of the National Cultural Relics Commission of the Ministry of Culture. Jia received international recognition for his work when he was elected a Foreign Associate of the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1994. Jia played a central role in the process of designating the Peking Man site of Zhoukoudian a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. For many years, he also acted as the conservator of the Zhoukoudian Archives.

Jia Lanpo died of a cerebral hemorrhage on 8 July 2001. His cremated remains were placed at Zhoukoudian beside those of his fellow paleontologists Pei Wenzhong and Yang Zhongjian.

Selected BIbliography

中國猿人 (北京人) [Chinese Ape Man (Peking Man)]. Shanghai, Long men shu dian, 1950. [with later editions in

“Notes on the Human and Some Other Mammalian Remains from Changyang, Hupei.” Vertebrata PalAsiatica 1 (1957): 247-258.

Jia, Lanpo, Gai Pei, and You Yuzhu. “Report of excavations in Shiyu, Shanxi — A Palaeolithic Site.” Acta Archaeologica Sinica 1 (1972): 39–60.

The Cave Home of Peking Man. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1975.

Jia Lanpo and Wang Jian, 西侯度: 山西更新世早期古文化遗址 [Xihoudu: A Lower Paleolithic Site in Shanxi Province]. Beijing: Wen wu chu ban she, 1978.

La Caverne de l’homme de Pékin. Pékin: Éditions en langues étrangères, 1978.

Jia Lanpo, Wei Q., and Li C. “Report on the Excavation of the Hsuchiayao Man Site in 1976.” Vertebrata PalAsiatica 17 (1979): 277-293.

Early Man in China. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1980.

Jia Lanpo and Loïc Chotard, Nos ancêtres les chinois: la préhistoire de l’homme en Chine. Paris: Éditions France-Empire, 1982.

贾蘭坡舊石器时代考古论文選 [The palaeoliths of China, selected works of Jia Lanpo]. Beijing : Wen wu chu ban she : Xin hua shu dian Beijing fa xing suo fa xing, 1984.

Jia Lanpo, and Huang Weiwen, 1985a, “On the Recognition of China’s Palaeolithic Cultural Traditions.” In Wu Rukang and J. W. Olsen, (eds.). Palaeoanthropology and Palaeolithic Archaeology in the People’s Republic of China. Pp. 259-265. Orlando: Academic Press, 1985.

Jia Lanpo and Ho Chuan Kun, “Lumière nouvelle sur l’archéologie paléolithique chinoise.” L’Anthropologie 94 (1990): 851-860.

Secondary Sources

Lanpo Jia; Xiang Lin; Mingsheng Li. 世纪老人的话. 贾兰坡卷. Shenyang Shi: Liaoning jiao yu chu ban she, 2000.

大師導讀: 北京猿人: 賈蘭坡和他的考古大發現. Taibei shi: Long tu teng wen hua, 2011.

Dennis A. Etler, “Jia Lanpo (1908-2001),” American Anthropologist 104 (2002): 297–299.

John W. Olsen. “A Tribute to Jia Lanpo (1908-2001).” Asian Perspectives 43 (2004): 191-196.

* I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Lo Kuan-Hung in translating Chinese sources.