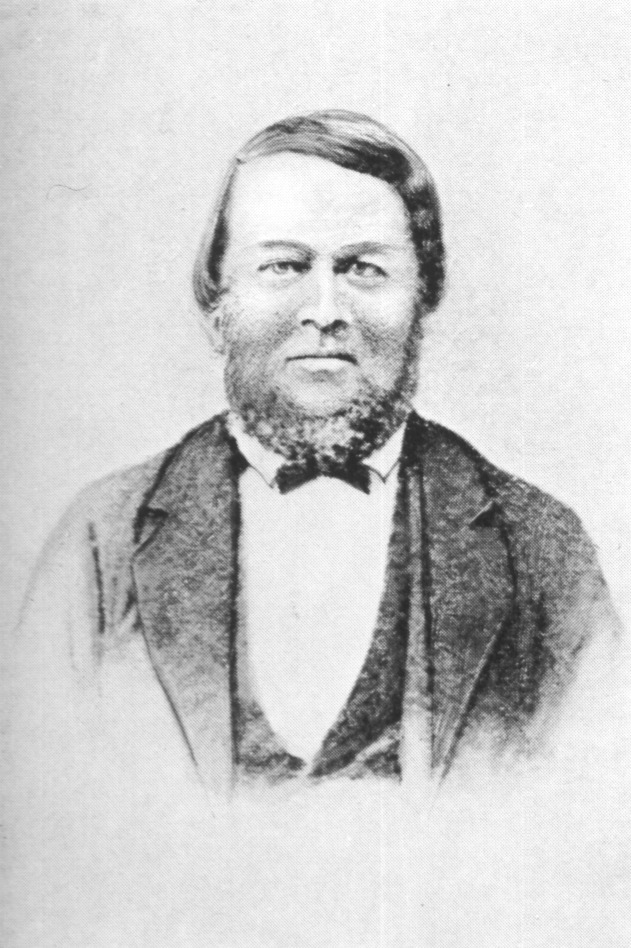

Hermann Schaaffhausen (1816–1893)

Matthew Goodrum

Hermann Joseph Schaaffhausen was born 18 July 1816 in Koblenz, Germany. His father, Hubert Josef Schaaffhausen, was a wealthy merchant in Koblenz, and his mother was Anna Maria Wachendorf. In 1834 he began his medical studies at the University of Bonn where he studied zoology with Georg August Goldfuss, anatomy with August Franz Joseph Karl Mayer, surgery and surgical anatomy with Karl Wilhelm Wutzer, and mental illness and anthropology with Christian Friedrich Nasse. After completing his studies at Bonn, Schaaffhausen entered the University of Berlin in 1837 where he studied under Johannes Müller. He received his medical doctorate on 31 August 1839 with a dissertation titled De vitae viribus. The following year, he passed the state medical exam, and during the autumn, he visited Dresden, Prague, Vienna, Munich, and Würzburg. He spent six months studying in Paris in 1842 and also visited London for three months in the summer of 1843. Schaaffhausen was appointed a Privatdozent (lecturer) of physiology at the University of Bonn in 1844 and was promoted to Professor extraordinarius in 1855. He was made Geheimer Medicinalrath (Privy Medical Councilor) in 1868. Schaaffhausen remained a professor on the medical faculty at the university for the remainder of his career, lecturing on physiology, anatomy, medicine, and anthropology. He lobbied the university for years to establish a chair in anthropology but the Medical Faculty rejected his pleas, in part due to his support for the idea of human evolution.

Early in his career, Schaaffhausen discussed the idea of biological evolution in an article published in 1853 titled “Ueber Beständigkeit und Umwandlung der Arten” (On the Constancy and Transformation of Species) where he declared that the immutability of species was not proven. This was several years before Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species (1859). Schaaffhausen presented a paper at the meeting of the Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte in 1867 titled “On the Anthropological Questions of Our Time” where he argued that humans had developed from animal ancestors, but he also believed that humans represent the pinnacle of creation and that a divine plan directed the emergence of humans. He argued, as Darwin did, that the biological and intellectual differences that separate humans from other animals are quantitative, not qualitative, and he noted the simian traits that one could observe in the anatomy of both prehistoric peoples and existing “lower races” (Schaaffhausen 1867).

Much of Schaaffhausen’s research dealt with anthropology and the study of prehistoric humans in Europe. This was at a time when anthropology was emerging as a distinct science and becoming professionalized. Paul Broca in France and Rudolf Virchow in Germany were founding institutions and establishing the methodology of anthropology. They emphasized the study of human races by making careful measurements of human bodies. For prehistoric skeletons, this meant the measurement of bones and especially the use of craniometry, the measurement and study of the form of human skulls. Schaaffhausen was one of the original members of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte (German Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory) when it was founded in 1869. He was a member of a commission organized by the Society to catalogue all the human skeletal remains found in Germany. Schaaffhausen was also involved in the discussion among German anthropologists over how to standardize the way anthropological measurements were taken, which led to the Frankfort Agreement in 1881, establishing an agreed method among German anthropologists for making craniometric measurements. He also worked to create a standard way of measuring the cranial capacity of human skulls.

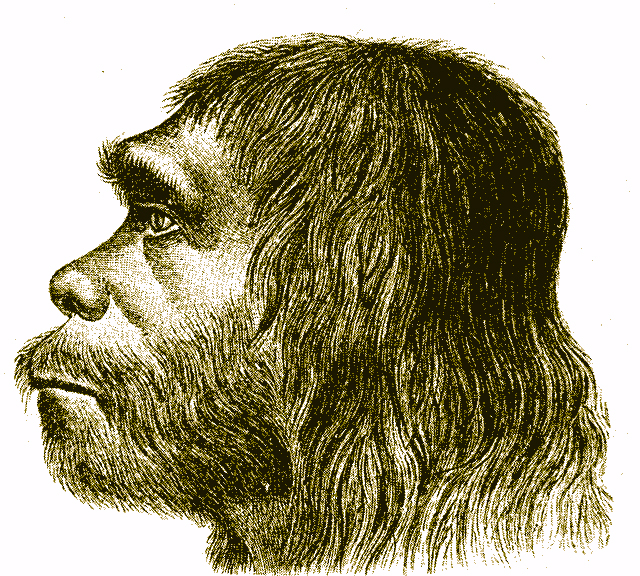

Today Schaaffhausen is best known for his contributions to paleoanthropology through his work on the original Neanderthal fossils. In 1856 workmen quarrying stone from the Feldhofer Grotte in the scenic Neander Valley, near Düsseldorf in northern Germany, unearthed human bones in the cave. Johann Carl Fuhlrott, a teacher at the Gymnasium in Elberfeld who had an interest in geology and paleontology, learned of the rare discovery and immediately went to recover the bones. He obtained the top portion of the skull, a clavicle and scapula, the right and left ulnae, a radius bone, the left pelvic bone, and the right and left femora. Fuhlrott noted that the bones appeared to be completely fossilized, which meant the bones might be extremely old. Recognizing the potential scientific significance of these fossils, Fuhlrott brought them to Schaaffhausen for analysis. Schaaffhausen was struck by the shape of the cranium and the evidence for the great geological age of the bones. Fuhlrott and Schaaffhausen presented papers describing the fossils and the geology of the Feldhofer Cave at a meeting of the Niederrheinische Gesellschaft für Natur- und Heilkunde (Lower Rhine Medical and Natural History Society) in Bonn in 1857. Schaaffhausen published a paper comparing the Neanderthal bones with other prehistoric human skeletons (Schaaffhausen 1858), and Fuhlrott published a paper in the Verhandlungen des Naturhistorischen Vereins der preussischen Rheinlande und Westphalens in 1859, describing the geology of the Feldhofer cave and how the bones were discovered. Fuhlrott and Schaaffhausen argued that the Neanderthal fossils dated from what was then called the Glacial Period, which meant they lived at the same time as mammoths, wooly rhinoceros, and other extinct Ice Age animals.

Schaaffhausen identified several features where the Neanderthal cranium differed markedly from modern human skulls. It possessed prominent eyebrow ridges and the long sloping shape of the cranium indicated that it belonged to what Schaaffhausen called a savage and barbarous race of ancient human. He concluded that the Neanderthals were the original wild race of humans that lived in Europe before other peoples migrated into Europe in prehistoric times. The Neanderthal fossils generated considerable debate among anthropologists across Europe. Rudolf Virchow, the most influential anthropologist in Germany, argued that the distinctive morphological features of the bones were the result of pathology and not evidence that they belonged to a distinct primordial human race. Uncertainty over how to interpret the Neanderthal fossils continued for decades, and it was not until after the discovery of additional Neanderthal fossils at the end of the nineteenth century, along with the growing acceptance of the theory of evolution, that the Neanderthals began to be accepted as an extinct species of ancient human.

Schaaffhausen continued over the next thirty years to write about the Neanderthal fossils and to investigate other prehistoric human remains in an attempt to understand the populations that inhabited Europe during prehistory. He examined the partial Neanderthal mandible that Karel Maška discovered in 1880 in the Šipka cave, in Moravia (today part of the Czech Republic) (Schaaffhausen 1880, 1883). He also discussed the human cranium unearthed at Podbaba, near Prague, in 1883 that was described by Anton Fritsch (Schaaffhausen 1883, 1884). This fossil was initially believed to date from the Paleolithic although its geologic age remains uncertain. He recognized the significance of the two Neanderthal skeletons discovered in a cave near the Belgian village of Spy in 1886, which helped to clarify the anatomy of the Neanderthals and vindicated his original opinion that they represented a distinct type of human (Schaaffhausen 1887a, 1887b). Schaaffhausen also examined the partial human skeleton that Alexander Makowsky excavated from the Pleistocene loess deposits under the Franz-Joseph Strasse in Brünn (Brno), Moravia, in 1891(Schaaffhausen 1892).

Schaaffhausen was a member of several prominent German and foreign scientific societies. In 1845 he became a member of the Naturhistorischen Vereins der preussischen Rheinlande und Westphalens (Natural History Society of the Rhineland and Westphalia), which was located in Bonn, and in 1864 he became a member of the Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft (Senckenberg Nature Research Society), which is located in Frankfurt am Main. He was also a member of the Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande (Association of the Friends of Antiquity in the Rhineland), the Niederrheinische Gesellschaft für Natur- und Heilkunde (Lower Rhine Society for Natural and Medical Science), and the Historischer Verein für den Niederrhein (Historical Association for the Lower Rhine). Schaaffhausen was elected a member of the prestigious Kaiserlichen Leopoldinisch-Carolinischen Deutschen Akademie der Naturforscher on 25 November 1873. He was elected a foreign member of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (Anthropology Society of Paris) in 1863, an honorary member of the Anthropological Society of London in 1868, and a member of the Société impériale des naturalistes de Moscou (Imperial Society of Naturalists of Moscow) in 1874. In addition to his scientific activities, Schaaffhausen served as president of the Vereins der Rettung zur See (Association for Rescue at Sea).

Schaaffhausen served as co-editor for many years of the influential journal Archiv für Anthropologie. He was also one of the founders of the Rheinischen Landesmuseums located in Bonn. He published many important scientific papers during his career, but no major monographs. Many of his most important anthropological papers were published as a book titled Anthropologische Studien [Anthropological Studies] in 1885. Schaaffhausen died in Bonn on 26 January 1893. He was buried in the Old Cemetery in Bonn. Among those who attended his funeral were Kaiser Wilhelm II, the Queen of Sweden, and many of his colleagues from the university.

Selected Bibliography

“Ueber Beständigkeit und Umwandlung der Arten.” Verhandlungen des Naturhistorischen Vereins der Preussischen Rheinlande und Westfalens 10 (1853): 420-451.

“Ueber die Entwickelung des Menschengeschlechts und die Bildungsfähigkeit seiner Rassen.” Amtlichen Bericht über die ein und dreissigste Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte in Bonn (1857): 73-81.

“Ueber die Hautfarbe des Negers und über die Annäherungen der menschlichen Gestalt an die Thierform.” Amtlichen Bericht über die ein und dreissigste Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte zu Göttingen [1854] (1860): 103-114.

“Zur Kenntnis der ältesten Rasseschädel.” Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin (1858): 453–478.

“On the Crania of the Most Ancient Races of Man.” The Natural History Review 1 (1861): 155-176.

“Ueber den Zustand der wilden Völker” Archiv für Anthropologie 1 (1866): 161-190.

“Ueber die anthropologischen Fragen der Gegenwart.” Archiv für Anthropologie 2 (1867): 327-41.

“Ueber die Urform des menschlichen Schädels.” Abhandlungen aus dem gebiete der naturwissenschaften, mathematik und medicin als Gratulationsschrift der Niederrheinischen Gesellschaft für Natur- und Heilkunde zur feier des Fünfzigjährigen Jubiläums der Königlich Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität (1868): 59-84.

“Ueber germanische Grabstätten am Rhein.” Jahrbücher des Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande 44 (1868): 86-162.

“Die Lehre Darwin’s und die Anthropologie.” Archiv für Anthropologie 3 (1868): 259-266.

“Darwinism and Anthropology.” Journal of the Anthropological Society of London 7 (1868): cviii-cxi.

“On the Development of the Human Species and the Perfectibility of Its Races.” Anthropological Review 7 (1869): 366-375.

“Ueber die Methode der vorgeschichtlichen Forschung.” Archiv für Anthropologie 5 (1871): 113-128.

“Sur l’anthropologie préhistorique.” Congrès d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques Compte Rendu [1872] (1873): 535-549.

Wilhelm Baer, Hermann Schaaffhausen, and Friedrich von Hellwald. Der vorgeschichtliche Mensch. Ursprung und Entwickelung des Menschengeschlechtes. Leipzig: O. Spamer, 1874.

“Der Neanderthaler Fund.” Correspondenz-Blatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte (1878): 116-120.

“Funde in der Schipkahöhle in Mähren.” Verhandlungen des naturhistorischen Vereins der Preussischen Rheinlanden und Westfalens 37 (1880): 260-264.

“Ueber den menschlichen Kiefer aus der Schipka-Höhle bei Stramberg in Mähren.” Verhandlungen des naturhistorischen Vereins der Preussischen Rheinlanden und Westfalens 40 (1883): 279-305.

“Die Schädel aus dem Löss von Podbaba und Winaric in Böhmen.” Verhandlungen des Naturhistorischen Vereines der Preussischen Rheinlande und Westfalens (1884): 364-379.

Anthropologische Studien. Bonn: Marcus, 1885.

Der Neanderthaler Fund. Bonn: Marcus, 1885.

“Ueber den Schädel von Spy.” Correspondenzblatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 18 (1887a): 161-162.

“Ueber die Funde menschlicher Skelette bei Spy.” Verhandlungen des Naturhistorischen Vereins der Preussischen Rheinlande und Westfalens (Korrespondenzblatt) 44 (1887b): 75-76.

“Vorgeschichtliche Funde in Mähren.” Verhandlungen des Naturhistorischen Vereins der Preussischen Rheinlande und Westfalens 49 (1892): 26-37.

Secondary Sources

Johannes Ranke, “Professor Dr. Hermann Schaaffhausen,” Jahrbücher des Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande 94 (1893): 1-42.

Johannes Ranke, “Schaaffhausen, Hermann.“ In Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, (Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften), (1893), vol. 35, pp. 748-751.

E. Roth, “Hermann Schaaffhausen,” Leopoldina 29 (1893): 168-173.

Hermann Hüffer, “Hermann Schaaffhausen.” Annalen des Historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein 56 (1893): 189-194.

Rudolf Virchow, “Hermann Schaaffhausen,” Verhandlungen der Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte (1893): 85-86.

Ursula Zängl-Kumpf, Hermann Schaaffhausen (1816–1893) – die Entwicklung einer neuen physischen Anthropologie im 19. Jahrhundert, Frankfurt am Main: R. G. Fischer, 1990.

Ursula Zängl-Kumpf, “Hermann Schaaffhausen (1816-1893) und die frühe Geschichte des Faches Anthropologie.” Anthropologischer Anzeiger 50 (1992): 335-354.

Ursula Zängl-Kumpf, ” Schaaffhausen, Hermann (1816-1893).” In Frank Spencer (ed.). History of Physical Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. 2 vols. New York: Garland Publishing, vol. 2, pp. 909-911.

Ursula Zängl-Kumpf, “Hermann Schaaffhausen (1816-1893) and the Neanderthal Finds of the 19th Century,” in Ralf W. Schmitz (ed.), Neanderthal 1856-2006 (Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2006), pp. 45–53.