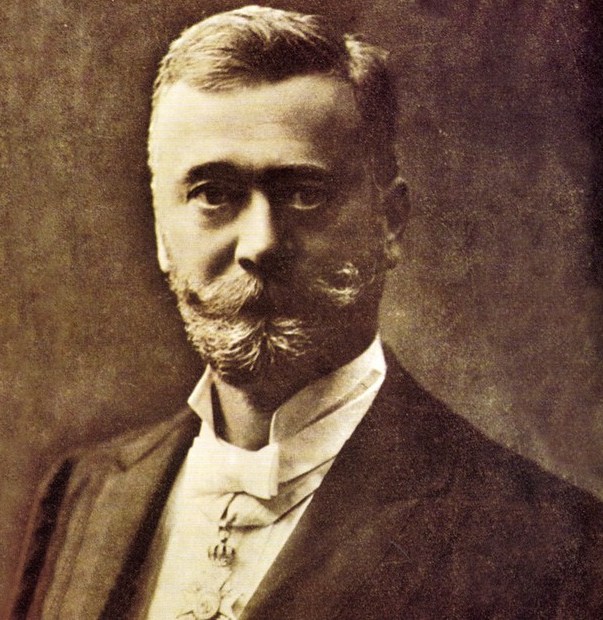

Hermann Klaatsch (1863–1916)

Matthew Goodrum

Hermann August Ludwig Klaatsch was born in Berlin on 10 March 1863, the son of August Hermann Martin Klaatsch, a prominent Berlin physician, and Julie Klaatsch. After graduating from the Königliche Wilhelms-Gymnasium in Berlin in 1881, Klaatsch entered the University of Heidelberg where he studied medicine and comparative anatomy under Carl Gegenbaur. He completed his medical degree in 1885, and for the next three years, he worked as an assistant to Heinrich Wilhelm Waldeyer at the Anatomical Institute at the University of Berlin. He was also able to spend some time working in the laboratory of the physician and anthropologist Rudolf Virchow and at the Augusta hospital. During this period Klaatsch was interested in zoology and spent several months studying at the biological station of Villefranche, near Nice. In 1888 Klaatsch accepted Gegenbaur’s invitation to return to Heidelberg to be an assistant at the Anatomical Institute at the university. He began teaching human anatomy at the University of Heidelberg in 1890 and was promoted to the status of professor extraordinarius in 1895.

Klaatsch soon became interested in human paleontology, human evolution, and physical anthropology. This led him to travel to England, France, and Croatia where he visited important anthropological collections. In a paper read before the Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte in 1899, Klaatsch rejected the thesis supported by Darwin, Huxley, and Haeckel that humans evolved from the anthropoid apes. He argued instead that the human, ape, and monkey lineages had diverged from an original prosimian ancestor. He would later change his opinion on human evolution, however. Klaatsch’s interest in evolutionary theory led him to publish a book on Darwin’s theory, Grundzüge der Lehre Darwin’s, which was so successful that several editions were printed between 1900 and 1919. The Neanderthals were becoming an increasingly important subject in paleoanthropology at this time, and at the meeting of the Anatomischen Gesellschaft [Anatomical Society] held in Bonn in 1901, Klaatsch presented a paper on the limb bones of the Neanderthal specimen (Klaatsch, 1901b). At the same meeting, German anthropologist Gustav Schwalbe presented a paper on the Neanderthal cranium. Schwalbe, unlike Klaatsch, became a strong supporter of the idea that Neanderthals were direct ancestors of modern humans. Klaatsch also published several papers on the large collection of Neanderthal fossils discovered by the Croatian paleontologist Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger at Krapina, in Croatia, beginning in 1899 as well as a paper comparing the Neanderthal crania unearthed by Maximin Lohest and Marcel de Puydt in the Grotte de Spy in Belgium in 1886 with Neanderthal crania from Krapina. (Klaatsch 1901a, 1902a, 1902c).

European archaeologists were also embroiled in a debate over the validity of eoliths, chipped pieces of flint found in Tertiary deposits that some archaeologists argued were human artifacts. Klaatsch was interested in these claims and traveled to France and Belgium in 1902 and 1903 to investigate some of the more important collections of eoliths. Klaatsch had also become friends with Otto Schoetensack, a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg who was convinced that Australia was the homeland of the first human beings and that the human race in fact originated there. Klaatsch and Schoetensack discussed the potential value of traveling to Australia to find evidence for this theory. Motivated by his interest in prehistoric humans, Klaatsch traveled throughout Australia and Tasmania between 1904 and 1907, but because of poor health, Schoetensack was unable to accompany him. During his travels, Klaatsch studied the Aborigines, especially their morphology and culture, and examined Aboriginal rock art. He also used this opportunity to collect a large quantity of ethnographic objects that he sold to German museums. After leaving Australia, Klaatsch made a brief visit to the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) where he visited the site where Dutch anatomist Eugène Dubois discovered the Pithecanthropus erectus fossils in 1891-92.

Upon returning to Germany in 1907, Klaatsch accepted a position as professor of anatomy and anthropology at the University of Breslau (now Wrocław, in Poland). There he also served as curator of the collections of the Anatomical Institute and of the Ethnographic Museum. He published a paper on the stone artifacts used by contemporary Aboriginal Australians and Tasmanians, comparing them with prehistoric artifacts from Europe (Klaatsch, 1908a). He also published important papers on the skull of the Aboriginal Australians (Klaatsch, 1908b) and a comparison of the morphology of Aboriginal Australian skulls with Neanderthal skulls (Klaatsch, 1908c). Anthropologists throughout the nineteenth century relied upon craniometry, which was a set of techniques and measurements of skulls that utilized a variety of instruments, to investigate human races. Klaatsch used craniometry in his study of Australian and Neanderthal skulls, but in the course of his investigations, he modified these craniometric methods. Unlike some anthropologists, he emphasized comparative anatomy and was skeptical of what he saw as the excessive use of statistical data by some anthropologists. He outlined his ideas about craniometry in a paper published in 1909 (Klaatsch 1909a).

Klaatsch assisted Otto Schoetensack in the analysis of a fossil human mandible that workmen found in a quarry at Mauer, near Heidelberg, in 1907. The peculiar morphology of the fossil and its great age led Schoetensack to conclude it belonged to an entirely new species of hominid that he named Homo heidelbergensis. When the Swiss amateur archaeologist Otto Hauser unearthed a human skeleton at the Paleolithic site of Le Moustier, in the Vézère valley in France in 1908, he invited Klaatsch to collaborate with him in studying these fossils. Klaatsch examined the skeleton, which was nearly complete, and although he acknowledged that it shared many features in common with Neanderthal fossils found throughout Europe, he considered this skeleton to represent a distinct type that he named Homo mousteriensis Hauseri (Klaatsch and Hauser, 1909; Klaatsch, 1909c). Then in 1909, Hauser discovered yet another human skeleton while excavating at Combe-Capelle, also located in the Vézère valley. This skeleton was found with the remains of a necklace made of shells as well as Aurignacian artifacts. Klaatsch was again invited to study the fossils and concluded they represented an entirely new Paleolithic human race that he called Homo aurignacensis Hauseri (Klaatsch and Hauser, 1910). Klaatsch suggested that this “Aurignacian race,” which differed from both the Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons, had migrated into Europe from Asia before the arrival of Cro-Magnons into Europe (Klaatsch, 1910). When Hauser excavated a partial human skeleton associated with Aurignacian artifacts at the Paleolithic site of La Rochette in 1910, Klaatsch and Walter Lustig published a description of these fossils as well (Klaatsch and Lustig, 1914).

In addition to his examination of hominid fossils, Klaatsch also formulated some original ideas about human evolution. He rejected German anthropologist Rudolf Virchow’s influential assertions that the Neanderthals were pathological and not an extinct species of human. But he also rejected the claims made by Gustav Schwalbe and Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger that the Neanderthals were the direct ancestors of modern humans. Klaatsch argued that modern humans had evolved from Cro-Magnons and that Cro-Magnons were contemporaries of the Neanderthals. He also suggested there were Homo aurignacensis fossils among the Krapina Neanderthals discovered by Gorjanović-Kramberger. Klaatsch also promoted a polygenist (polytypic) theory of human evolution, which argued that current human races had separate evolutionary origins. He also opposed the theories of Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, and Ernst Haeckel, that humans evolved from an anthropoid ape ancestor. Instead, Klaatsch suggested that humans and the anthropoid apes evolved from a hypothetical common ancestor he named Proanthropus, which was more human-like than apelike in its morphology. The human and anthropoid lineages probably diverged in the Eocene or Oligocene period, with the human line becoming more humanlike but the separate ape lineages degenerating from the common ancestor and becoming more apelike. He went on to propose that a hypothetical Asian group of humanlike apes he called Propithecanthropus evolved through two branches, the eastern evolved into orangutans as well as the Aurignacian race of humans and modern Mongoloid races, whereas the western branch evolved into gorillas as well as the Neanderthals and Negroid races. Because of this conception of human evolution Klaatsch was forced to reject Pithecanthropus erectus as a direct human ancestor.

Klaatsch published several books on human evolution and human prehistory for a general audience, including Die Anfänge von Kunst und Religion in der Urmenschheit [The Beginnings of Art and Religion in Earliest Humanity] published in 1913 and Der Werdegang der Menschheit und die Entstehung der Kultur [The Development of Mankind and the Birth of Culture] published posthumously in 1920. Klaatsch was elected a member of the Leopoldina in 1903. He remained at the University of Breslau until his death of pneumonia on 5 January 1916 in Eisenach, Germany.

Selected Bibliography

Grundzüge der Lehre Darwin’s: Allgemein verständlich dargestellt. Mannheim: J. Bensheimer, 1900.

“Bericht über den neuen Fund von Knochenresten des alt- diluvialen Menschen von Krapina in Kroatien.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft 53 (1901a): 44–46.

“Das Gliedmassenskelet des Neanderthalmenschen.” Anatomischer Anzeiger 19 (1901b): 121–154.

“Occipitalia und Temporalia der Schädel von Spy vergleichen mit denen von Krapina.” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 34 (1902a): 392–409.

“Das Hinterhauptbein–Osoccipitaledes Menschen von Krapina.” Mittheilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 32 (1902c): 194–200.

“Entstehung und Entwickelung des Menschengeschlechtes.” In: H. Kraemer (ed.) Weltall und Menschheit, Volume 2. Pp. 3–338. Berlin: Deutsches Verlagshaus Bong & Co, 1902.

“Die Steinartefakte der Australier und Tasmanier, verglichen mit denen der Urzeit Europas.” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 40 (1908a): 407-436.

“The Skull of the Australian Aboriginal.” Reports from the Pathological Laboratory of the Lunacy Department, New South Wales Government 1, part 3 (1908b): 43-167.

“Das Gesichtsskelett der Neandertalrasse und der Australier.” Verhandlungen der Anatomischen Gesellschaft 22 (1908c): 223-273.

Otto Hauser and Hermann Klaatsch. “Der neue Skelettfund Hausers aus dem Aurignacien.” Praehistorische Zeitschrift 2 (1908): 180-182.

“Kranio-Morphologie und Kranio-Trigonometrie” Archiv für Anthropologie 7 (1909a): 1-28

“Die Fortschritte der Lehre von der Neandertalrasse (1903– 1905).” Ergebnisse der Anatomie und Entwicklungsgeschichte 17 (1909b): 431–462.

Hermann Klaatsch and Otto Hauser, “Homo mousteriensis Hauseri: ein altdiluvialer Skelettfund im Departement Dordogne, und seine zugehorigkeit zum Neandertaltypus.” Archiv für Anthropologie 7 (1909): 287-297.

“Preuves que l’Homo mousteriensis Hauseri appartient au type du Néandertal.” L’Homme prehistorique (1909c): 10-16.

“Die neueste Ergebnisse der Palaontologie des Menschen und ihre Bedeutung fur das Abstammungsproblem” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie Xl1. [1909], p. 537).

Hermann Klaatsch and Otto Hauser, “Homo aurienacensis Hauseri, ein palæolithischen Skelettfund aus dem unteren Aurignacien der Station Combe-Capelle bei Montferrand (Périgord).” Praehistorische Zeitschrift 1 (1910): 273–338.

“Die Aurignac-Rasse und ihre Stcllung im Stammbaum der Menschheit.” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 42 (1910): 513–577.

“Menschenrassen und Menschenaffen.” Korrespondenz-Blatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 41 (1910): 91–99.

“Die Stellung des Menschen im Naturganzen.” In O. Abel et al. (eds.). Die Abstammungslehre. Zwölf gemeinverständliche Vorträge über die Deszendenztheorie im Licht der neueren Forschung. Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1911 pp. 321–483.

Die Anfänge von Kunst und Religion in der Urmenschheit. Leipzig: Verlag Unesma, 1913.

Morphologische Studien zur Rassendiagnostik der Turfanschädel. (Abhandlungen der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin). Berlin: Verl. der Königl. Akad. der Wiss., 1913.

Hermann Klaatsch and Walter Lustig, “Morphologie der paläolithischen Skelettreste des mittleren Aurignacien der Grotte von La Rochette, Dep. Dordogne.” Archiv für Anthropologie 41 (1914): 81-126.

Hermann Klaatsch and Adolf Heilborn. Der Werdegang der Menschheit und die Entstehung der Kultur. Berlin: Bong & Co., 1920. [Translated into English by Joseph McCabe, The Evolution and Progress of Mankind. New York: Stokes, 1923.]

Secondary Sources

Georg Thilenius. “Hermann Klaatsch.” Korrespondenz-Blatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 47 (1916): 1-4.

Richard Wegner. “Hermann Klaatsch.” Anatomischer Anzeiger 48 (1915-6): 611-623.

Hugo Mötefindt. “Hermann Klaatsch.” Naturwissenschaftliche Wochenschrift (1916): 297-299.

Theodor Mollison “Hermann Klaatsch.” Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1916): 263-264.

Eugen Fischer. “Hermann Klaatsch.” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 47 (1916): 385-390.

Bruno Oetteking. “Hermann Klaatsch.” American Anthropologist 18 (1916): 422-425.

Hans Hahne. “Klaatsch, Hermann zum Gedächtnis.” Mannus. 7 (1916): 366-375.

Hans Seger. “Hermann Klaatsch als Anthropologe.” Prähistorische Zeitschrift 7 (1916): 241-246.

Gaston Mayer. “Klaatsch, Hermann.” In Neue Deutsche Biographie. Vol. 11, p. 697-8. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1977.

Walter Jankowsky. “Hermann Klaatsch und die Entwicklung der modernen Anthropologie.” In Walter Jankowsky (ed.). Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiet der Anthropologie. Darmstadt 1962, Pp. 25–31.

Brigitte Stehlik. “Hermann Klaatsch and the Tiwi, 1906.” Aboriginal History 10 (1986): 59-77.

Corinna Erckenbrecht. “Vom Forschungsziel zur Sammelpraxis. Die Australienreise und die völkerkundliche Sammlung Hermann Klaatsch im Lichte neuer Quellen.” Kölner Museums-Bulletin. Berichte und Forschungen aus den Museen der Stadt Köln 3 (2006): 25–36.

Corinna Erckenbrecht. Auf der Suche nach den Ursprüngen: die Australienreise des Anthropologen und Sammlers Hermann Klaatsch 1904-1907. Koln: Gesellschaft für Völkerkunde, 2010.