Heinrich Wankel (1821–1897)

Matthew Goodrum

Jindřich (Heinrich) Wankel (he published primarily under the name Heinrich) was born on 15 July 1821 in Prague, in what at that time was the Austrian Empire. His father, Damian Wankel, was a provincial councilor in Prague whose family was originally from Bavaria, in Germany. Wankel’s mother, Magdalena Schwarzová (Schwarz), was Czech and instilled a sense of pride for Czech culture in her son. Wankel attended the gymnasium (German secondary school) in the Malá Strana (Lesser Town) district in Prague, and after graduating he entered the University of Prague (at that time called Charles University in Prague) in 1841 where he obtained a degree in medicine in 1847 with a thesis on the diseases of the eardrum. He stayed on at the university in order to get a degree in surgery in 1848. Wankel studied under the anatomist Josef Hyrtl and briefly worked as his assistant after completing his degree. He also took a position in a Prague hospital, and during the revolution of 1848, he treated the wounded from the barricades in Prague. Wankel met the Czech painter Josef Mánes at this time, and they became close friends, often traveling together. It was during this period that Wankel set out on a trip to Vienna and stopped in Moravia. He fell in love with the region, and in October 1849, he moved first to the town of Jedovnice where he worked as a physician at the iron smelting factory owned by Hugo Karl Salm-Reifferscheidt. Two years later, he moved to Blansko, and on 17 August 1851, he married Eliška Šímová (Elisabeth Schima).

Wankel retained his association with the influential Salm family, who served as patrons of culture and science in Blansko. Hugo František Salm-Reifferscheidt had created the František Museum in Brno in 1817. Wankel attained some renown as a physician by suppressing the cholera epidemics that raged in Blansko in 1850, 1851, and 1855 as well as for his treatment of the wounded and sick during the Austrian wars of 1859-1866. For this work, he was awarded the Goldene Verdienstkreuz (Golden Merit Cross) by the emperor Franz Joseph I in 1866. Wankel began to explore the many local caves in the Moravian karst in 1849, and this began his life-long work of exploring and excavating Moravian caves. One of the first sites Wankel examined were the Sloup-Šošůvka Caves where he unearthed Pleistocene animal fossils, including cave bear, cave lion, and hyena. This initiated his interest in paleontology just at a time when European paleontologists were becoming increasingly interested in the fossil fauna of the Ice Age. At a centenary commemoration of the birth of the German geologist Abraham Werner that was organized by a group of Brno naturalists in the town of Adamov (Adamsthal) in 1850, Wankel read a paper on his paleontological discoveries and displayed a reconstructed skeleton of a cave bear.

In 1850, Wankel established a laboratory at his home to facilitate his study of the Pleistocene fossils he was now discovering in large numbers from Moravian caves. These fossils had been mined and used for spodium in a nearby sugar refinery for some time before he began his investigations. Wankel set about devising ways to prepare and preserve the fossils he was collecting. He began to reconstruct their skeletons, and soon he was preparing skeletons for museums. As Wankel’s research expanded Salm-Reifferscheidt offered financial support as well as miners to assist with the excavation work, and Wankel’s growing collection was housed in one of the buildings on the grounds of the Blansko castle. Meanwhile, Wankel began to excavate new caves, often accompanied by his friend Josef Mánes. In 1856 Wankel surveyed the so-called Macocha abyss, a sinkhole 138 meters deep that is part of a vast underground system formed by the Punkva River, which cuts its way through the Moravian karst near the town of Vilémovice. Wankel presented a paper on his cave discoveries before the Werner-Vereins zur Geologischen Durchforschung von Mähren und Schlesien (Werner Association for the Geological Research of Moravia and Silesia) in 1858 and later donated a cave bear skeleton to the Association. He published a number of scientific papers on the Moravian caves and his paleontological discoveries as well as articles for a general audience (Wankel 1856; 1860; 1861; 1868a). Some of these popular works were illustrated by the Czech painter and illustrator Bedřich Havránek (Friedrich Hawranek).

Almost immediately after Wankel began to explore Moravian caves he also began to find prehistoric artifacts. This was just at the time when other European geologists were finding crude stone tools in Pleistocene deposits containing extinct animal bones, which was compelling them to accept the idea that humans had lived during the Ice Age. Wankel visited the exhibition of prehistoric artifacts organized by the French archaeologist Gabriel de Mortillet at the Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1867. There he saw the collection of Paleolithic, Neolithic, and other prehistoric objects. Wankel published an account of the exhibit that also discussed the research of Jacques Boucher de Perthes in the Somme valley, the excavations conducted by Édouard Lartet and Henry Christy in the Vézère valley, and the discovery of the Neanderthal specimen in Germany (Wankel 1868b). Wankel also noted the similarity of some Paleolithic artifacts from France with stone artifacts he had unearthed from a Moravian cave called Býčí skála (Bull Rock cave), and this prompted him to renew his excavations there.

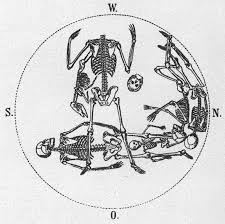

Wankel conducted excavations at Býčí skála from 1867 to 1873. During the course of his work, he distinguished two distinct periods represented in the cave’s deposits. One dated to the Pleistocene and contained Paleolithic artifacts while the other dated to the Iron Age (Hallstatt). In the Pleistocene deposits, he found stone axes and bone tools as well as fragments of crude pottery associated with the bones of cave bear and cave lion, which he considered to be evidence that humans had coexisting with these animals. But Wankel achieved the greatest renown for the discovery of a Hallstatt period burial in another section of Býčí skála. In 1869 two cousins, Gustav and Arnošt Felkl, had found a statuette of a bronze bull in the cave. So Wankel obtained funds for new excavations from Johann II of Liechtenstein, who owned the land. In 1872 Wankel unearthed an Iron Age Hallstatt burial dating to around the 6th century BCE in the entrance chamber of the cave. The grave contained one male skeleton along with the skeletons of forty young women. The burial also contained the skeletons of two horses, the remains of a chariot, offerings of grain, textiles, ceramic and metal vessels, jewelry (including bronze bracelets), and glass and amber beads. These objects are now in the collections of the Naturhistorisches Museum (Natural History Museum) in Vienna. Wankel interpreted this as the grave of a nobleman and that young women had been ritually killed to accompany him (Wankel 1871). This interpretation was disproved by further research at the end of the twentieth century. Wankel also suggested that the bronze bull found in the cave indicated that the site had been a cult site, perhaps similar to the cult of Apis in Egypt, but this idea was severely criticized, and he soon abandoned it. Wankel presented a paper on his discoveries at Býčí skála at the Russian Archaeological Congress held in Kiev in 1874.

Wankel excavated a large number of caves and prehistoric burials in Moravia throughout the 1870s and 1880s. He conducted excavations periodically in Výpustek Cave from 1869 until 1882. There he unearthed Neolithic stone tools and some bone artifacts, along with Pleistocene animal bones. Wankel excavated some tombs near Rajhrad (Raigern) in 1872 where he unearthed the skeletons of a man, a woman, and three children mixed together with the bones of a piglet. The tomb also contained a polished stone axe and pottery. The male skeleton appeared to have been decapitated, which led Wankel to interpret the burial as a Bronze Age Celtic human sacrifice (Wankel 1873). In 1876 he excavated Eve’s cave, which is located near Býčí skála. There he unearthed reindeer and horse bones associated with flint knives and shards of pottery, as well as some human bones. Wankel dated these finds to the late Paleolithic, a period referred to at this time as the Reindeer Age (Magdalenian). In another part of the cave, Wankel discovered cave bear bones associated with flint knives, which further indicated that humans were contemporaries of the cave bear in Moravia (Wankel 1877). After noticing a young female skull among the Býčí skála human skeletons that showed evidence of trepanation, he wrote a paper on the implications of this discovery (Wankel 1878). Soon afterwards Wankel visited the collection of human skulls in the museum in Prague and found two prehistoric skulls from Bilin, in Bohemia, that displayed evidence of trepanation (Wankel 1879b).

Wankel excavated a prehistoric tomb lined with stones that contained five human skulls, an iron knife, and clay objects at Bořitov, near Blansko in 1878. He conducted the first excavations of Kůlna Cave in 1880 and sent the stone tools he found there to the Naturhistorisches Hofmuseum in Vienna. (The Moravian archaeologist Martin Kříž conducted extensive further excavations there from 1881 to 1886.) Wankel also began excavations at Pekárna (Kostelik) cave after an initial exploration by Moravian archaeologist Jan Knies encountered archaeological finds there. Wankel unearthed broken bones belonging to horse, reindeer, and arctic fox mixed with hundreds of stone knives and axes, harpoons, as well as carved bones and reindeer antler and some shards of crude pottery that he dates to the late Reindeer Age (Magdalenian) (Wankel 1881).

In 1879 Wankel discovered the open-air archaeological site of Předmostí (Predmost). Predmost consists of loess deposits and limestone bluffs located in the Bečva river valley near Přerov, in eastern Moravia. He conducted excavations there from 1880 to 1882 and again in 1884 and 1886. Karel Maška, who had assisted Wankel in some of his investigations, conducted further excavations at Predmost from 1882 to 1895. When Wankel discovered the site, it was being exploited as a quarry for the extraction of loess and limestone. Sadly, hundreds of wagonloads of mammoth bones from the site were also being extracted to produce spodium (which was used for the whitening of sugar) or were pulverized to produce fertilizer. Some remarkable objects found during this commercial extraction were sent to private collectors. In the course of his excavations, Wankel unearthed large numbers of mammoth bones and artifacts made from stone and bone, as well as charcoal from hearths and the bones of various other extinct animals.

Wankel noticed distinct cut marks on the mammoth bones, which he interpreted as evidence that these animals had been butchered by humans. Then in 1884 Wankel unearthed a partial human mandible lying under a mammoth femur. He argued that the mandible dated from the same period as the mammoth bones. Wankel initially dated the Predmost finds to the “Mammoth Age,” and he argued that Predmost was a place where humans had hunted and butchered mammoths (Wankel 1885a). Wankel’s discoveries at Predmost attracted the attention of other European prehistorians, including the Dutch naturalist Japetus Steenstrup, who visited Predmost in 1888. Steenstrup published two papers, rejecting Wankel’s suggestion of mammoth hunters and arguing instead that Predmost was a sort of mammoth cemetery and that long after the extinction of the mammoths, Neolithic humans had exploited the site for mammoth ivory, much as the Yakut people of Siberia continued to do in modern times (Steenstrup 1889; 1890). Wankel eventually modified his interpretation of the finds from Predmost, partially in response to the critique of Steenstrup, and suggested that people from the Reindeer Age came to collect the mammoth bones (Wankel 1890). However, new excavations conducted by Karel Maška demonstrated that the mammoth and human remains at Predmost did indeed date from the same period. The German anthropologist Hermann Schaaffhausen, who is best known for his description of the Neanderthal fossils found in Germany in 1856, conducted an examination of the human mandible from Predmost, and a full description of this specimen was conducted by the Czech anthropologist Jindřich Matiegka in 1934. The animal fossils and human artifacts Wankel collected at Predmost were sent to the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien (Anthropological Society in Vienna), to the museum in Olomouc (Olmütz), and to the Moravské zemské muzeum (Moravian Land Museum) in Brno (Brünn). The human mandible was sent to the museum in Olomouc.

During the course of his paleontological and archaeological investigations, Wankel presented papers on many of his discoveries at the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien, but he also published accounts in articles for a more general audience. Wankel also published several books on prehistory. Wankel’s best-known book was Bilder aus der Mährischen Schweiz und ihrer Vergangenheit (Images from the Moravian Switzerland and Its Past), which was published in 1882 with illustrations by his friend Josef Mánes. Written for a general audience, Wankel describes the geology of the caves he had explored and the extinct animal fossils he discovered. He then discusses his archaeological discoveries, beginning with descriptions of Paleolithic artifacts and the Ice Age inhabitants of Moravia and proceeding through the Neolithic and Bronze Ages to portray the people and their manner of living during Moravian prehistory.

In his Beitrag zur Geschichte der Slaven in Europa (Contribution to the History of the Slavs in Europe), published in 1885, Wankel argued that the Slavs were present in Moravia from prehistoric times and did not arrive during the migrations of the 5th century, as was commonly believed by many European scholars. He suggested that their original homeland was beyond the Carpathian Mountains, and when they migrated into central Europe, the only people present there were the remnants of the Paleolithic inhabitants of the region. Many German archaeologists rejected Wankel’s claims, which led him to engage his critics over this. Wankel’s final book, Die Praehistorische Jagd in Mahren (The Prehistoric Hunt in Moravia), published in 1892, summarizes his ideas about the Paleolithic inhabitants of Moravia based upon his researches. Much of the book addresses his discoveries at Predmost and the arguments surrounding the association of mammoth bones and human artifacts at the site.

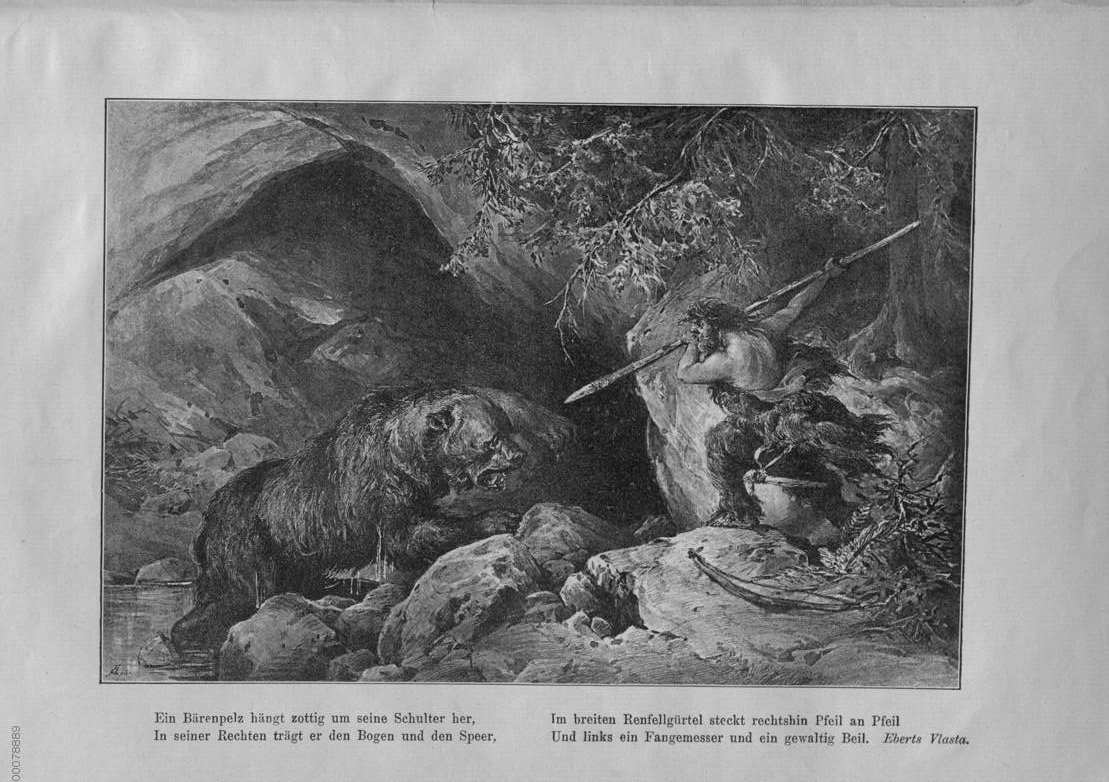

Wankel traveled widely throughout his life and participated in many scientific conferences and exhibitions. During a trip to Constantinople, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt in 1869, he studied the archaeological ruins in these regions. Wankel displayed some of his archaeological and paleontological discoveries at the Weltausstellung (World Exhibition) held in Vienna in 1873, where he received a medal for his exhibit. He then displayed his archaeological and paleontological collection at the Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte in Graz (Congress of German Naturalists and Physicians in Graz) in 1875. Following this he exhibited his collection at the international anthropological exhibition and congress held in Moscow in 1879. At the anthropological meeting held in Berlin in 1880, Wankel exhibited the objects from Býčí skály. He sent an exhibit to the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893, and his depiction of the “First Hunt,” which was accompanied by a display of a cave bear skull with the tip of a stone spearhead stuck into it as well as other Paleolithic artifacts from Moravia, was honored with a medal (Wilson 1901). Wankel influenced the important National Ethnographic Exhibition that was held in Prague in 1895, and his fellow Moravian prehistoric researchers, Karel Maška, Jan Knies, Martin Kříž, and Innocenc Ladislav Červinka Červinka were all involved in the event.

Wankel was a member of many prominent scientific and cultural institutions. Perhaps most importantly, he was one of the first members of the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien (Anthropological Society in Vienna), which was founded in 1870. Wankel presented many of his paleontological and archaeological discoveries to the Society. He also became a corresponding member of the influential Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte (German Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory) when it was founded in Mainz, Germany, in 1870. He was a member of the Zoologisch-Botanische Gesellschaft (Zoological-Botanical Society) in Vienna from 1856 to 1876. He became a member of the Society as a result of research he conducted on the eyeless insects, spiders, and crustaceans found in some Moravian caves. Wankel was a member of the Werner-Vereins zur Geologischen Durchforschung von Mähren und Schlesien (Werner Association for the Geological Research of Moravia and Silesia), as well as a corresponding member of the Kaiserlich Königlichen Geologischen Reichsanstalt (Imperial Royal Geological Institute) in Vienna. He was appointed Curator of the Central-commission zur Erforschung und Erhaltung der Kunst-und Historischen Denkmale (Central Commission for Research and Preservation of Art and Historic Monuments) in 1885. The Commission was established by the Vienna Academy of Sciences in 1850 to prevent the destruction of historic monuments, including prehistoric antiquities.

Wankel was a corresponding member of the Královská česká společnost nauk (Royal Bohemian Society of Sciences) as well as an honorary member of the Imperial Russian Anthropological Society in Moscow. Wankel and his wife founded the čtenářsko-pěveckého spolku Rastislav (Rastislav Readers ‘and Singers’ Association) in Blansko in 1862, which was created with the intent to revive Czech culture. Wankel was elected an honorary member of the Včela Čáslavská, a museum and archaeological association located in the town of Čáslav, in Bohemia, that was established in 1864 to protect local historical monuments. Wankel and the Moravian writer and ethnographer Jan Havelka founded the Vlastenecký spolek musejní v Olomouci (Patriotic Museum Association in Olomouc) in 1883, and Wankel edited the Association’s journal for several years. The Association and its museum served as an important center for Czech researchers interested in archaeology and anthropology.

Wankel served as a member of the municipal council of Blansko from 1861 to 1883. He retired from his position as physician in Blansko and moved to Olomouc (Olmütz) in 1883. Following the move to Olomouc, financial difficulties compelled Wankel to sell his extensive collection of objects amassed from his many excavations. It consisted of hundreds of stone tools, hundreds of bronze artifacts, and hundreds of Iron Age objects, hundreds of pieces of pottery, bone tools, Pleistocene animal fossils, as well as human skeletons, and around fifty skulls (from Býčí skála and Raigern as well as other sites). Wankel wanted to sell the collection to the František Museum in Brno, where Moritz Trapp had served as curator since 1864, but the museum could not afford to buy the collection. Wankel approached the museum in Prague, but they would not purchase the collection either. The abbot of the Rajhrad monastery, Günter Kalivoda, offered to buy it for the local Franciscan Museum, but the abbot died suddenly in April 1883, so the sale fell through. Through the efforts of Josef Szombathy, curator of the Prehistoric Collection of the Naturhistorisches Hofmuseum (now the Narurhistorisches Museum) in Vienna, much of Wankel’s collection was sold to the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien for 12,000 guilders, which then donated them to the Naturhistorisches Hofmuseum. The remaining part of the collection was sold by Wankel’s wife shortly after his death in 1897 (Stloukal and Szilvássy 1984).

During the course of his long career studying Moravian prehistory, Wankel came to know some prominent scientists. He was friends with Count Aleksei Sergeyevich Uvarov, the founder of the Moscow Archaeological Society, as well as Dmitry Nikolayevich Anuchin, the founder of anthropology as a scientific discipline in Russia. Wankel corresponded with German anthropologist and prehistorian Rudolf Virchow. He also influenced the young generation of Czech Paleolithic researchers that included Karel Maška, Jan Knies, and Martin Kříž. His grandson, Karel Absolon, became an influential Czech archaeologist and speleologist. Wankel’s paleontological and archaeological research garnered international recognition and the Danish naturalist Japetus Steenstrup called Wankel the “Father of Austrian Prehistory.” In 1892, Wankel suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. Wankel died in Olomouc on 5 April 1897. He is buried in the Central Cemetery in Olomouc-Neředín, in a common grave with his son-in-law Jan Havelka and Ignát Wurm.

Selected Bibliography

“Ueber die Fauna der mährischen Höhlen.” Verhandlungen der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 6 (1856): 467-470.

“Beiträge zur Fauna der mährischen Höhlen.” Lotos 10 (1860): 105-122, 137-143.

“Beiträge zur österreichischen Grotten-Fauna.” Sitzungsberichte der Akademie der Wissenschaften mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse 43 (1861): 251-265.

“Die Slouper Höhle und ihre Vorzeit.” Denkschriften der mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften 28 (1868a): 95-131.

“Der mensch der postpliocänen Periode und die Pariser Ausstellung.” Lotos 18 (1868b): 18–23, 37–46.

“Prähistorische Alterthümer in den mährischen Höhlen.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 1 (1871): 266-282, 309-314, 329-343.

“Der Menschenknochenfund in der Býčískálahöhle.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 1 (1871): 101-105.

“Eine Opferstätte bei Raigern in Mähren.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 3 (1873): 75-94.

“Gleichzeitigkeit des Menschen mit dem Höhlenbären in Mähren.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 7 (1877): 1-6.

“Der Bronze-Stier aus der Bycískála-Höhle.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 7 (1877): 125-154.

“La contemporaneité de l’homme avec l’ours des cavernes, en Moravie.” Matériaux pour l’histoire primitive et naturelle de l’homme 12 (1877): 137-138.

“Ein prähistorischer Schädel mit einer halbgeheilten Wunde auf der Stirne höchstwahrscheinlich durch Trepanation entstanden.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 7 (1878): 86-95.

“Prähistorische Eisenschmelz- und Schmiedestätten in Mähren.” (“Prehistoric iron smelting and forging facilities in Moravia”) Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 8 (1879a): 289-324.

“Ueber die angeblich trepanirten Cranien des Beinhauses zu Sedlec in Böhmen.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 8 (1879b): 352-360.

“Prähistorische Funde in der Pekárna-Höhle in Mähren. ” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 10 (1881): 347-348.

Bilder aus der Mährischen Schweiz und ihrer Vergangenheit. Vienna: Holzhausen, 1882.

“Prvni stopy lidské na Moravë.” Časopis Vlastivědného spolku musejního Olomouc 1 (1884): 2-7, 41-49, 89-100, 137-147.

Beitrag zur Geschichte der Slaven in Europa. (Olmütz: Fürst-Erzbischöfl. Buch- u. Steindruckerei, 1885.

“Der Mammutjäger in Mähren.” Kosmos (1885a): 114-118.

“Die Mamuthlagerstätte bei Predmost in Mähren.” Correspondenz-blatt der deutsehen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 21 (1890): 33-36.

Die Praehistorische Jagd in Mahren. Olmütz, Selbstverlag, 1892.

(Other Sources Cited):

Japetus Steenstrup “Mammuthjaeger-Stationen ved Predmost.” Oversigt over det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Forhandlinger (1888): 145-212.

Japetus Steenstrup, “Die Mammuthjäger-Station bei Předmostí im österreichischen Kronlande Mähren.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 20 (1890): 1-31).

Thomas Wilson, “A Cave-Bear Skull Exhibited by Dr. Wankel, of Austria.” Reprort of the Committee on Awards of the World’s Columbian Commission. 2 vols. Vol. 1, pp. 333-334. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901.

Jindřich Matiegka, Homo predmostensis, Fosilní clovck z Predmostí na Moravf, Díl I. Prague: Nákladem ceské akademie vfd a umfní, 1934.

Secondary Sources

Moris Trapp, “Med.-Dr. Heinrich Wankel.” Notizen-Blatt der Historisch-Statistischen Section der Kaiserlich-Königliche Mährisch-Schlesische Gesellschaft zur Beförderung des Ackerbaues, der Natur- und Landeskunde (1878): 33-36.

Constantin von Wurzbach, “Wankel, Heinrich.” In Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich. Vol. 53, pp. 70-74. Vienna: Kaiserlich-königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1886.

“M. U. Dr. Jindřich Wankel.” Časopis Vlastivědného spolku musejního v Olomouci 14 (1897): 113-118.

“Jindř. Wankel (obituary).” Nové Jllustrované Listy (29 May 1897): 263-264.

Lubor Niederle, “Dr. Jindřich Wankel.” Časopis Společnost přátel starožitností českých v Praze 5 (1897): 30-31.

“Dr. Jindřich Wankel.” Národopisný sborník českoslovanský (1897): 197.

Valerie Absolonová and Věra Bednářová, “Blanenská léta Med. Dr. Jindřicha Wankla (kritický pohled do života a práce).” Vlastivědný věstník moravský 21 (1970): 182-208.

Vratislav Grolich, MUDr. Jindřich Wankel, otec moravské archeologie, 150. Blansko: Okresní vlastivědné museum, 1971.

Milan Stloukal and Johann Szilvássy, “Sammlung Wankel in der anthropologischen Abteilung des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien.” Anthropologie 22 (1984): 51-71.

Johannes Mattes, ” Wankel, Heinrich (Jindřich).” Wissenskulturen des Subterranen: Vermittler im Spannungsfeld zwischen Wissenschaft und Öffentlichkeit. Ein biografisches Lexikon. Pp. 529-31. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2019.