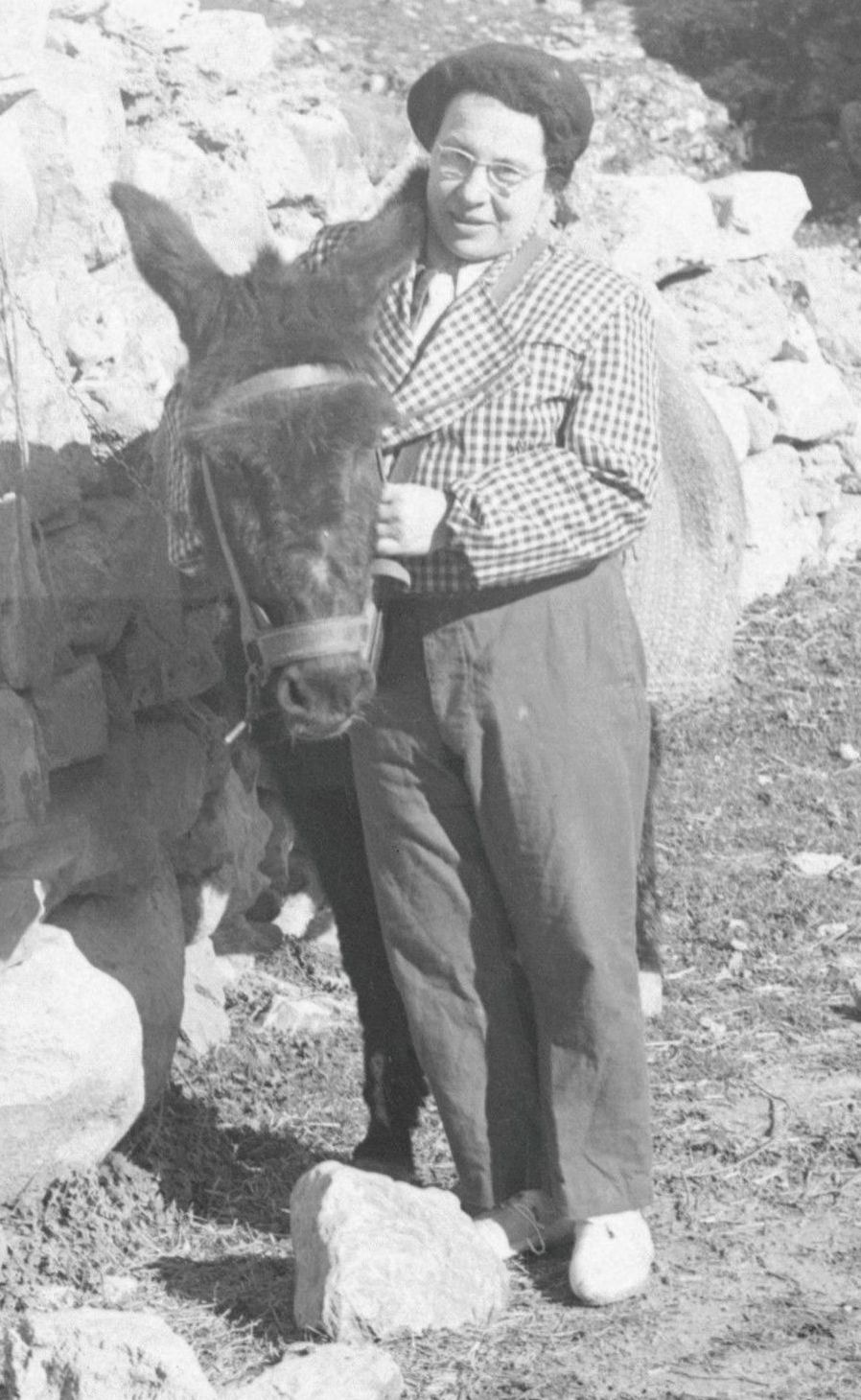

Germaine Henri-Martin (1902–1975)

Matthew Goodrum

Germaine Henri-Martin was born on 8 July 1902 in Paris, France. Her father, Léon Henri-Martin, was a physician and an archaeologist who devoted many years to excavating the Paleolithic site of La Quina. He was one of the founders of the Société Préhistorique Française (French Prehistoric Society) and became known for his work on the Mousterian artifacts from La Quina, and the discovery of fossils belonging to Neanderthals, including a partial skeleton. Her mother, Lucie-Marie-Louise Henri-Martin (née Huet), assisted in the excavations at La Quina and while Léon Henri-Martin was serving as a doctor at the front during the First World War, Lucie-Marie-Louise discovered the skull of a Neanderthal child at La Quina. Germaine Henri-Martin grew up living in Paris, but in 1905 her father bought the archaeological site of La Quina, located about thirty kilometers southeast of the town of Angoulême, in the department of Charente, and for the next thirty years, he conducted excavations there. The family spent so much time there that he eventually purchased the beautiful old structure known as the Logis du Peyrat, located near the site of La Quina, and transformed it into a country house. Léon Henri-Martin also established a Laboratoire d’Études de Paléontologie Humaine on the site to hold the growing collection of archaeological artifacts and animal fossils. This laboratory, which welcomed many researchers over the years who came to inspect its collections, became associated with the École Pratique des Hautes Études in 1925. Germaine spent much of her childhood observing and even helping in her father’s excavations at La Quina.

As a young woman, Henri-Martin trained as a concert violinist, but after her father’s death in 1936, she reluctantly abandoned this career to take over the Laboratoire d’Études de Paléontologie Humaine. She also turned her efforts entirely to investigating Paleolithic sites in the region. She is best known for her work at the Grotte de Fontéchevade, which she excavated from 1937 to 1953. Several archaeologists had previously explored the cave at Fontéchevade, located about twenty kilometers north of La Quina, including Louis Durousseau-Dugontier who worked there from 1902 to 1910. The deposits in the cave at Fontéchevade consisted of layers possessing Châtelperronian, Aurignacian, and Mousterian artifacts overlaying a deep set of deposits containing a distinctive type of stone tool. Henri-Martin invited the French prehistorian Henri Breuil, a long-time friend of her father, to examine these artifacts, and he identified them as belonging to tool-type known as the Tayacian. Breuil had designated a “Tayacian industry” in the 1930s on the basis of stone flakes found in the lowest levels of the Paleolithic site of La Micoque, located near the French village of Les-Eyzies-de-Tayac. Henri-Martin’s excavations of the Tayacian levels at Fontéchevade, however, made it the best-known Tayacian site (Henri-Martin 1949a; 1949b). She also recovered many animal fossils from this Tayacian layer that indicated it dated from the Riss-Würm interglacial period.

In August 1947 Henri-Martin unearthed two hominid cranial fossils in this Tayacian layer. The first, called Fontéchevade I, was a small fragment of a frontal bone with the glabella, while the second, called Fontéchevade II, was a partial calotte (frontal and parietal). Fontéchevade I possessed features more like modern humans, while Fontéchevade II possessed more archaic features like those found in Neanderthals. Henri-Martin invited French paleoanthropologist Henri Vallois to study these fossils. Vallois published several papers describing them and utilized the dissimilarity between them to support the so-called presapiens hypothesis (Vallois 1947a; 1947b; 1949). The presapiens hypothesis was the idea, supported by many paleoanthropologists during the early twentieth century, that modern humans existed at least since the early Pleistocene, and as a consequence, hominids such as the Neanderthals and even Homo erectus could not be direct ancestors of Homo sapiens. At the end of her excavations, Henri-Martin published a comprehensive report titled La Grotte de Fontéchevade, which appeared in the series of memoires published by the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine (Institute of Human Paleontology). It consisted of three parts published in two volumes between 1957 and 1958. Henri-Martin wrote the first part, which covered the archaeology of the site. Henri Vallois wrote the second part covering the hominid fossils, while the third part covering geology and paleontology was written by Henriette Alimen, Camille Arambourg, and A. Schreuder. Throughout her career, Henri-Martin maintained relationships and collaborations with scientists who possessed expertise in areas outside her training. In addition to consulting Henri Breuil for his views on artifacts and Henri Vallois for the analysis of the hominid fossils, she had important relationships with several prominent women archaeologists. These included the English archaeologist Dorothy Garrod, who occasionally assisted Henri-Martin with the excavations at Fontéchevade and frequently consulted the collections in the Laboratory at La Peyrat. Suzanne de Saint-Mathurin, was an archaeologist who conducted research with Breuil and Garrod, and also occasionally joined the excavations at Fontéchevade and later at La Quina. Henri-Martin also sought the assistance of Henriette Alimen, a geologist and paleontologist who did important her work on sediment analysis and the formation of the deposits at Fontéchevade.

Henri-Martin made several trips to Yugoslavia to see Paleolithic sites. The Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti) invited her to participate in excavations of Risovača Cave, located just outside the town of Aranđelovac in central Serbia, in the 1950s. Risovača Cave is one of the most important Paleolithic sites in Serbia, and the first excavations there were initiated in 1953 by archaeologist Branko Gavela and speleologist Radenko Lazarević, followed by the archaeologist Srećko Brodar in 1955. Henri-Martin also traveled with Suzanne de Saint-Mathurin and Dorothy Garrod to see Paleolithic sites in Spain. Dorothy Garrod and Henri-Martin excavated Paleolithic deposits in the cave of Ras-el-Kelb in Lebanon in 1959. While accompanying the archaeologist Raymond Lantier at the Solutrean site of Roc-de-Sers in 1951 they found a number of new rock carvings, adding to the large collection of bas-relief images of animals collected from the site by her father in the 1920s (Lantier 1952).

Henri-Martin resumed work at La Quina in 1953, although she had conducted occasional work there in previous years, and continued her father’s excavations there until her death in 1975. Through her various excavations Henri-Martin was able to expand the collection of artifacts and fossils housed at the Laboratory created by her father in La Peyrat. Like her father, Henri-Martin also welcomed visiting scientists to the Laboratory and to her excavation sites. The Henri-Martin family donated the entire collections of the Laboratory to the Musée des Antiquités nationales (Museum of National Antiquities) in 1976.

Henri-Martin was a member of several prominent scientific institutions, including the Société Préhistorique Française (French Prehistoric Society); the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (Anthropology Society of Paris), the Société Archéologique et Historique de la Charente (Archaeological and Historical Society of Charente), and the Association Française pour l’Avancement des Sciences (French Association for the Advancement of the Sciences). She was awarded the Prix Bonnet (Bonnet Prize) by the Académie des Sciences in 1949, and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) awarded her its Bronze Medal in 1958. She was named Maître de Recherche (Senior Research Fellow) at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique in 1963. She was made a Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters), created by the French government in 1957 to recognize people who made significant contributions to the arts and sciences. Germaine Henri-Martin died in the Paris suburb of La Celle-Saint-Cloud on 5 November 1975.

Selected Bibliography

“L’Homme fossile Tayacien de la grotte de Fontéchevade.” Compte-Rendu des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 225 (1947): 766-767.

“Mise au jour d’une calotte crânienne humaine fossile dans un niveau du Paléolithique ancien de la Grotte de Fontéchevade (Charente).” Gallia 5 (1947): 175-179.

“L’industrie tayacienne de Fontéchevade.” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 46 (1949): 353-363.

“L’industrie tayacienne de Fontéchevade.” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 93 (1949): 112-114.

“Nouvelles constatations sur le Paléolithique inférieur de la Grotte de Fontéchevade (Charente).” Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences 230 (1950): 2234-2236.

Germaine Henri-Martin, Henri Vallois, Henriette Alimen, Camille Arambourg, and A. Schreuder, La Grotte de Fontéchevade (Archives de l’Institut de Paléontologie Humaine). 2 vols. Paris: Masson, 1957-1958.

“La grotte de Fontéchevade.” Quaternaire 2 (1965): 211-216.

Other Works Cited

Henri Vallois, “Un Homme fossile Tayacien en Charente.” L’ Anthropologie 51 (1947a): 373–374.

Henri Vallois, “Une Importante découverte en paléontologie humaine” Nature (1947b): 397-398.

Henri Vallois, “The Fontéchevade Fossil Men.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 7 (1949): 339-362.

Raymond Lantier, “Les fouilles du sanctuaire solutréen du Roc-de-Sers (Charente) en 1951.” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (1952): 303-307.

Secondary Sources

Suzanne de Saint-Mathurin, “Germaine Henri-Martin.” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 73 (1976): 97-106.

Paulette Marquer, “G. Henri Martin, 1902-1975.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (1975): 405-406.

“Henri-Martin (Germaine).” In François Julien-Labruyère and Robert Allary (eds.), Dictionnaire biographique des charentais et de ceux qui ont illustré les Charentes.

P. 677. Paris: Croît vif, 2005.

Philip G. Chase, André Debénath, Harold L. Dibble, Shannon P. McPherron, The Cave of Fontéchevade: Recent Excavations and Their Paleoanthropological Implications. Chapter 1 “Introduction and Background.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.