Gerhard Heberer (1901–1973)

Matthew Goodrum

Gerhard Richard Heberer was born on 20 March 1901 in Halle (Halle an der Saale), Germany. He attended the Reform-Realgymnasiums in Halle from 1911 to 1919 and from May 1919 to February 1920 he was part of the Freikorps movement, which was a group engaged in suppressing leftist uprisings. He entered the University of Halle in 1920 where he studied zoology, comparative anatomy and genetics with the comparative morphologist and geneticist Valentin Haecker. He also studied anthropology and prehistory with Hans Hahne. Heberer completed his Ph.D. in Natural Sciences in 1924 with a dissertation titled Die Spermatogenese der Copepoden. I. Die Spermatogenese der Centropagiden nebst Anhang über die Oogenese bei Diaptomus castor. He was particularly interested in evolution and Valentin Haecker provided Heberer with a background in morphology and genetic theory. Hans Hahne introduced Heberer to the “racial science” that was growing in prominence in Germany in the early twentieth century. Hahne believed that race was the key to world history and this view helped shape Heberer’s early anthropological work. While he was a university student, Heberer became involved in several political and social organizations. He was one of the founders of the Deutschen Akademischen Gildenschaft (German Academic Guild) in 1920. He was also a leader of the Wandervogel, a völkich German youth movement that embraced the German Romantic movement’s attitudes about nature.

From 1924 to 1926, Heberer worked as an assistant at the Landesanstalt für Vorgeschichte (State Institute for Prehistory) in Halle. Heberer’s former professor Hans Hahne was the director of the museum, which changed its name to the Landesanstalt für Volkheitskunde (State Institute for the Study of Folklore) in 1934. This is where Heberer first became acquainted with paleoanthropology. In 1927, Heberer joined the “Sunda Expedition” to the Lower Sunda Islands, in Indonesia, which was organized by German biologist Bernhard Rensch. Heberer was given the responsibility for conducting anthropological studies of the local people, which included both morphological and ethnological studies. He took anthropometric measurements as well as hair and blood samples. This research eventually led to the publication in 1950 of Die Inland-Malaien von Lombok und Sumbawa (The Inland Malays of Lombok and Sumbawa). Heberer also collected copepods, a type of small aquatic crustacean, while the expedition’s other researchers collected thousands of mammals, birds, reptiles, and arthropods, many of them new to science. Following his work on the expedition, Heberer spent six months in 1928 at the Zoological Institute in Buitenzorg, located on the island of Java, which allowed him to travel throughout Southeast Asia.

Upon returning to Germany, Heberer was appointed first as a lecturer and then as an associate professor of zoology and comparative anatomy in the Zoological Institute, directed by Jürgen Wilhelm Harms, at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen. He was at Tübingen from 1928 to 1938. In addition to his teaching duties, he completed his habilitation degree (Venia legend) in zoology and comparative anatomy in 1931. While he continued to do research and teach on morphology, genetics and zoology Heberer was becoming increasingly interested in human prehistory and hominid evolution. From 1936 onward his courses in zoology and anthropology at the University of Tübingen began to reflect an increasing influence of Nazi Party ideology, manifested in an emphasis on racial biology and discussions of issues relating to human genetics. In addition to teaching at Tübingen, during the 1935-1936 academic year Heberer provisionally held the Chair of Zoology at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, filling in for Otto zur Strassen. He hoped to make the appointment permanent, but Catholic students at the university helped block his appointment to a permanent professorship, ostensibly because of his lectures supporting evolutionary theory. As a result of these events, Heberer returned to the University of Tübingen in 1936 and remained there until 1938. During this time, however, he spent brief periods at the zoological research stations in Naples and in Rovigno d’Istria in Italy.

By the early 1930s Heberer had come to the attention of some of the leading Nazis in Adolf Hitler’s regime. In 1933 he joined the SA (Sturmabteilung), the paramilitary wing of the Nazi party that played an important role in Hitler’s rise to power, and records show that Heberer remained a member until 1935. He then became a member of the NS-Lehrerbund (National Socialist Teachers League) and the NS-Dozentenbund (National Socialist German Lecturers’ League), which were organizations designed to exert political control over university education and make the National Socialist worldview the foundation of German education. During the course of his university career under the Nazi regime, Heberer was praised for having carried out his lectures in a determined National Socialist style. The SS (Schutzstaffel) became interested in his work in 1936 and Heberer became a member of the Nazi party (membership number 3,972,811) in June 1937. In April 1937 Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, personally intervened to make Heberer an SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) and appointed him to the staff of the SS Rassen und Siedlungshauptamt (Race and Settlement Main Office), which was a government agency responsible for safeguarding the “racial purity” of SS officers. In September 1938 Heberer was promoted to SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant) and in January 1942 to SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain). He was also appointed a member of Himmler’s SS-Forschungsgemeinschaft Deutsches Ahnenerbe (Research Society for German Ancestral Heritage), an elite quasi-scientific group that tried to prove Nazi racial theories by means of examining prehistoric finds and making anthropometric measurements.

In the autumn of 1938, Heberer was appointed a professor in the newly created Institut für Allgemeine Biologie und Anthropogenie (Institute for General Biology and Anthropogeny) at the Friedrich-Schiller University of Jena. He established the Institute upon arriving at the university and served as its director until 1945. After the Nazi’s came to power in Germany in 1933, the University of Jena became a model of an SS university, where Nazi principles came to dominate all academic disciplines. One of the most important of these disciplines was anthropology, where racial theories developed in previous decades became the scientific basis for Nazi ideology. Heberer’s colleagues at Jena included Karl Astel, professor of human genetics, Hans Günther, and Victor Julius Franz, all of whom supported a Deutschen Wissenschaft/Biologie (German science/biology). This was a Germanicized racial version of evolutionism that blended racial biology, anthropology, genetics, and eugenics. In fact, Karl Astel had initiated the effort to appoint Heberer a professor at Jena. Heberer also assumed responsibility for the Phyletisches Museum (Phylogenetic Museum) at the university, which had been established by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel in 1908. Heberer expanded the anthropological and archaeological collections of the university, but much of this was achieved by appropriating prehistoric objects from occupied countries during the war.

Heberer’s scientific endeavors while he was a professor at Jena fall into two categories, lectures and publications on “racial science” on the one hand and research on phylogeny and paleoanthropology on the other. The tone of his discussions as well as the inclusion of Nazi themes and vocabulary varied between these two categories, which appear to have been composed for two different audiences. Heberer’s biological and paleoanthropological research was valuable to the Nazi Party primarily because of his theory of the Indogermanic origins of the so-called Nordic race. As a result, his scientific work gave academic and scientific credibility to Nazi racial policies. Heberer was also among the group of scientists, which included Karl Astel and zoologist Victor Franz, the director of the Ernst Haeckel House, who founded the Ernst Haeckel-Gesellschaft (Ernst Haeckel Society) in 1942. The Society was created to promote Haeckel’s monist philosophy and its links to Nazi ideology.

With the German surrender at the end of World War II, Heberer became a Czech prisoner of war in Motol, an area of Prague. He was interned by the Allies from 1945 to 1947 in order to undergo de-Nazification as a result of his membership in the SS. In his de-Nazification records, it is clear that he was successful in convincing the tribunal that he had used his SS and Nazi Party affiliations to avoid being sent to the front and had engaged in racial science to gain favor with the authorities and to provide for his family. He was given a category V classification (non-incriminated person) after de-Nazification. Because he had published extensively in scientific journals without using Nazi jargon, his claims were accepted and he was able to return to Germany in 1947. In a biography of Heberer, Uwe Hossfeld claims that Heberer would have been more likely to have received a disqualification for teaching had he been released in Soviet-occupied East Germany, because his records would have been more readily accessible and the judges less sympathetic to his claims (Hossfeld 1997). After being released from his internment Heberer went to Göttingen.

Two years after returning to Germany, Heberer became a professor at the Georg-August University of Göttingen, where he also served as director of the Anthropologischen Forschungsstelle (Anthropological Research Centre) from 1949 until 1970. The word race no longer appeared in Heberer’s course offerings during his postwar years teaching at Göttingen. He conducted research and published extensively on evolutionary biology, hominid and ape phylogeny, and human evolution. His work was not well known outside of Germany, however, due to a lack of interaction between German scientists and their international scientific colleagues during the war years and to the fact that German scientists were often ignored after the war. Yet, Heberer did travel to many museums outside Germany as well as to excavation sites of early hominids in Africa. He visited Olduvai Gorge for several weeks in April and again in October and November 1961, where he discussed the recent discoveries made there by Louis and Mary Leakey. As a result of his travels, Heberer was able to acquire an extensive paleoanthropological collection of fossil casts at the University of Göttingen. Heberer was also a guest lecturer at the Free University of Berlin during the 1961-1962 academic year.

Early in his career Heberer conducted research on the cytogenetics and comparative morphology of the copepods. He increasingly became involved in human genetics and issues relating to racial science and the origin of the Indo-Europeans, especially during the Nazi era. However, his most influential work was in evolutionary biology and paleoanthropology. Heberer was a strong advocate of evolution and of applying evolutionary theory to explaining human origins and human nature. In 1931 he published a paper arguing that there is no fundamental difference between the animal soul (Tierseele) and the human soul (Menschenseele). Approaching the subject from the Darwinian evolutionary perspective he argued that the human brain, the material prerequisite for any cultural development, must be viewed as an adaptation to special environmental conditions and thus can be explained by natural or sexual selection. Therefore, according to Heberer, humanity has its phylogenetic roots not only morphologically but also psychically from ape ancestors (Heberer 1931).

From 1935 to 1944 Heberer conducted anthropological research that dealt with human racial types and the original homeland of the Indo-Europeans. Unlike earlier anthropologists, he introduced new ideas derived from the science of genetics as well as his own anthropological and prehistoric investigations. These include the anthropometric examination of the Mesolithic skeleton excavated in Bad Dürrenberg in 1934 (Heberer 1936), as well as a study of the Mesolithic human skeletons that were unearthed near Bottendorf in 1939 in graves that had been partly disturbed and apparently intermixed with Bronze Age graves (Heberer and Bicker 1941). Heberer also studied some human skeletons belonging to the Baalberg culture in order to identify their racial types (Heberer 1938a). The Baalberger culture derived its name from a burial mound located in Baalberge, a district of Bernburg (Saale), that contained burials dating to the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. During an excavation of the mound, called the Schneiderberg, in 1901 by the Bernburg History and Antiquity Society under the direction of Ferdinand Kälber, who was assisted by the historian and archaeologist Paul Höfer, ceramic vases of an archaeological culture were discovered that were later designated the Baalberger culture. The stratigraphy of the burial mound helped to clarify the chronology of the Middle German Neolithic period but questions remained about the racial identity of these prehistoric inhabitants of Germany. Additionally, Heberer conducted extensive craniometric and anthropometric studies on human skeletons found in archaeological sites belonging to the Corded Ware (Schnurkeramiker) and Linear Pottery (Bandkeramik) cultures (Heberer 1938b; 1939b; 1940a).

Heberer integrated what he learned from this research into the broader existing research on the origin of the Indo-European race to write Rassengeschichtliche Forschungen im indogermanischen Urheimatgebiet (Racial-Historical Research on the Indo-European Original Homeland) (1943). In this book Heberer argued that the Indo-Germanic people were identical with the Nordic race and that they originated during the Ice Ages in north-central Europe. He argued that the so-called Nordic race, which was said to occupy northern and central Germany, had originally developed from the proto-Germanic peoples of the Middle Stone Age (Mesolithic) who in turn developed into the Indo-Germanic people of the New Stone Age (Neolithic). He utilized evidence from prehistoric skeletons to support this thesis. Throughout this work, Heberer promoted the idea that human races, including the Nordic race, had developed through biological evolution. He believed that natural selection had operated on early humans during the Würm glacial period of the late Pleistocene and that Ice Age environmental conditions had played a crucial part in the development of the intellectual capacities of modern humans. In fact, Heberer was convinced that these conditions were essential to explaining the evolutionary development of the specific mental characteristics possessed by the Nordic race that made them superior to other races. He was also convinced that this process had occurred in Europe, and thus he rejected the Asian origin of the Indo-European race and instead argued that Europe was the “Urheimat” or original homeland of the Indo-Europeans.

Evolutionary biology permeated much of Heberer’s scientific work and by the 1940s evolutionary theory was undergoing a revolution with the emergence of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis. Beginning in the 1930s with the work of the American geneticist Sewall Wright and the Ukranian geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky, and continuing into the 1940s with the German biologist Ernst Mayr and the English biologist Julian Huxley among others, new discoveries from Mendelian genetics and population genetics were integrated into evolutionary theory to produce the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis. This new understanding of the evolutionary process and evolutionary mechanisms emphasized the importance of natural selection and adaptation. Heberer was one of the leading German biologists involved in promoting and extending this newly emerging conception of evolution. He discussed an idea called “additive typogenesis,” which argued that evolution is driven by small incremental changes over time (microevolution) and not by large mutational jumps (saltationism or Richard Goldschmidt’s “hopeful monsters”) and that infraspecific processes continue to act at higher taxonomic categories.

Heberer’s most influential contribution to evolutionary theory came through a monograph he edited titled Die Evolution der Organismen (The Evolution of Organisms) (1943). The first edition of this work brought together nineteen leading biologists, paleontologists, and anthropologists to address a wide range of questions relating to evolution. This was one of the first major works in the German language to discuss the new Modern Evolutionary Synthesis. Several of its papers promoted a Neo-Darwinian conception of evolution that emphasized the role of natural selection as well as a gradualist and adaptive version of evolution. Equally, it rejected alternative forms of evolutionism such as Lamarckism, orthogenesis, and saltationism, as well as metaphysical versions of evolution such as idealistic morphology and vitalist conceptions of evolution. This book also offered one of the first attempts to investigate anthropological questions from the perspective of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis. The chapters by Heberer on hominid phylogeny, Wilhelm Gieseler on paleontology, Christian von Krogh on comparative anatomy, and Hans Weinert on prehistoric anthropology and archaeology, devoted a great deal of attention to the hominid fossil record as an essential source of evidence for understanding the process of human evolution. These authors emphasized the role of natural selection, genetics, adaptation, phylogenetics, and the critical role of Ice Age environmental conditions in Europe in the evolution of humans. The first edition published in 1943 was only partially successful at modernizing paleoanthropology in Germany by integrating the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis into it. A second edition of Die Evolution der Organismen was published in 1959, with some new chapters and new authors. These first two editions were influential in Germany but had little effect outside Germany. A third edition was published in three successive volumes which appeared in 1967, 1971, and 1974. Heberer died in 1973 before the completion of the final volume, so the Göttingen anthropologist Christian Vogel and Tübingen anthropologist Wilhelm Gieseler completed the publication and partial revision of Volume 3, which was devoted to hominid phylogeny.

When Heberer became a professor at the University of Göttingen, after the disruption of Germany’s defeat in the war and his internment, he retained a strong interest in evolutionary theory. In 1949 he published a short book titled Was heißt heute Darwinismus? (What Is Darwinism Today?), which declared his affiliation with the leading proponents of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis, many of whom were in America. He also used this book to distance himself from Nazi political and scientific ideology and to align himself with mainstream western European science. However, Heberer also increasingly devoted his research to human evolution. Paleoanthropology was beginning a period of significant change in the 1950s. The hominid fossil record had expanded during the 1930s with the discovery of australopithecine fossils in South Africa, the excavation of numerous Homo erectus (Peking Man) fossils in China, and a variety of hominid fossils from Indonesia. Additionally, the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis was beginning to be integrated into paleoanthropology, which resulted in new ways of thinking about human evolution and hominid taxonomy. The symposium on “The Origin and Evolution of Man” held at Cold Spring Harbor in 1950 marks the opening of this new era of paleoanthropological research and many of these elements can be found in Heberer’s research during the 1950s and 1960s.

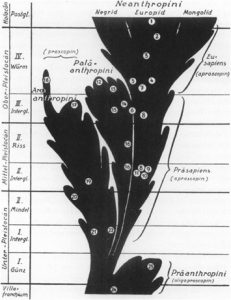

Heberer was interested in a variety of problems relating to hominid phylogeny and the processes that influenced human evolution. Heberer (1950b; 1951b; 1955) identified three main hominid lineages in the latter stages of human evolution, although he believed other minor lineages had probably also existed. These lineages were the Archanthropine (the pithecanthropines), the Palaeanthropine (Neanderthals and pre-Neanderthals) and the Presapiens. The Presapiens Hypothesis was a model of human evolution that was influential during the early twentieth century. It argued that anatomically modern humans (Presapiens) had existed at least since the early Pleistocene and therefore the Neanderthals, as well as the so called “Pre-Neanderthals” that existed during the Riss-Würm interglacial, could not be ancestral to modern humans since they had coexisted with the Presapiens. Heberer agreed with the other advocates of the Presapiens Hypothesis that the Swanscombe cranium, the fragments of which were discovered in England between 1935 and 1936, belonged to this Presapiens population of the early Pleistocene. He also embraced the Fontéchevade cranium, discovered in France in 1947 and described by French paleoanthropologist Henri-Victor Vallois, as further evidence of this Presapiens lineage. Heberer argued that these three hominid lineages had evolved in parallel in different geographical areas of the Old World during the Pleistocene. He believed that modern Homo sapiens had evolved from the Presapiens lineage only. Thus, Homo erectus and the Neanderthals were not direct ancestors of modern humans but extinct cousins (see the phylogenetic tree below).

Henri-Victor Vallois was one of the leading proponents of the Presapiens Hypothesis in the mid-twentieth century and Heberer agreed with many of Vallois’ views regarding human evolution. Heberer thought that the Presapiens and the Palaeanthropine lineages had diverged from the ancestral Archanthropine lineage at least by the early Middle Pleistocene if not the Lower Pleistocene. Heberer modified his views in later years and in 1965 he argued that the Presapiens lineage had evolved from a Neanderthaloid type during the Middle Pleistocene (Heberer 1965c). As evidence for this, Heberer suggested that the Steinheim cranium, a fossil discovered in Germany in 1933 that displayed a mixture of Neanderthal and modern human features, should be placed phylogenetically near the divergence of the Presapien and the Palaeanthropine lineages. There was considerable debate regarding the Neanderthals throughout the twentieth century and views about them were changing by the 1950s. Heberer believed that some specimens that had been identified as African and Asian Neanderthals—such as the Broken Hill cranium discovered in 1921, the Saldanha cranium discovered in South Africa in 1953, and the Ngandong fossils excavated in Indonesia between 1931 and 1933—should not be classified as Neanderthals. He argued that Neanderthals should refer only to fossils from Europe dating to the Würm glacial period.

Heberer was equally interested in the broader span of human evolution beginning with our earliest ape ancestors and proceeding to modern humans. He closely followed the discovery of new hominid and ape fossils and he was particularly interested in the fossils being discovered in Africa. In 1951 Heberer published Neue Ergebnisse der menschlichen Abstammungslehre (New Results in Human Descent), which covered a wide range of topics relating to human evolution. He begins with providing a comprehensive and detailed morphological description of many hominid fossils, especially the newly discovered specimens from South and East Africa. He then considers hominid phylogeny going all the way back to Propliopithecus, a gibbon-like ape that lived during the Oligocene. Heberer argued that the process of hominization had occurred from the late Miocene to the mid or late Pliocene, which resulted in the appearance of the australopithecines in the Upper Pliocene. He goes on to discuss the Pleistocene hominids and the evolution of Homo sapiens. Throughout this book, Heberer discusses the importance of population genetics in his discussion of human evolution. Interestingly, he suggested that evolution might occur at different rates in different hominid populations and at different times due to genetic factors.

The question of how humans had emerged from an ape-like ancestor—the hominization process—was an interest that Heberer shared with many paleoanthropologists of his generation. One of his major contributions to this problem was his idea of the Tier-Mensch-Übergangsfeld (Animal-Human Transition Field). This idea appears in papers that Heberer published from the 1950s through the 1960s, but it was outlined in detail in Heberer (1958). In this scheme Heberer recognized three phases of human evolution: the subhuman phase, the animal-human transition field, and the human phase. The subhuman phase consists of that period when hominids were mentally completely animals and their evolution occurred only as a result of natural selection, without any contribution from their own intentional actions. For Heberer, the animal-human transition field was that phase of hominid evolution when hominids attained the “human mental plane.” He believed this took place about three million years ago, or perhaps earlier during the Pliocene. Many events critical to the evolution of modern humans occurred during the animal-human transition field phase. Hominids inhabited a new adaptive environment, the savannah, which led to rapid anatomical and cognitive changes in these hominids. These included improved bipedalism, which meant that the hands were now free to use tools. According to Heberer, hominids during this phase also began to take some role in shaping their own evolution, most importantly they began to use tools and this eventually led to acquiring the ability to manufacture and modify tools. The final phase of human evolution, the human phase, began when our ancestors possessed all the qualities assigned to humans. Particularly, humans made tools with specific purposes in mind.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, paleoanthropologists placed great emphasis on the brain and the increasing size of the brain from apes to humans in their accounts of human evolution. The English anthropologist Arthur Keith introduced the idea of what he called the cerebral Rubicon. This was the minimum brain size, measured by the cranial capacity of fossil hominid skulls, for a hominid species to be considered human and be placed in the genus Homo. Keith argued that this minimum cranial capacity was 750cc and that crossing this cerebral Rubicon led to profound changes in hominid behavior, such as tool-use and tool-making, as well as cooperation and sharing behavior. Heberer acknowledged the value of Keith’s argument and he located the crossing of the cerebral Rubicon during the animal-human transition field phase. However, in several papers he suggested that brain volume alone was not a useful criterion for determining the animal-human transition (see for example Heberer 1952a). He argued that the mental ability of hominids could not be measured simply by measuring their brain volume, but should instead be determined by their brain complexity and functionality. Heberer identified the evolution of bipedalism as the critical factor in the hominization process, and bipedalism influenced brain evolution.

Once early hominids passed through the animal-human transition field phase of human evolution, Heberer argued that they reached a favorable adaptive plateau marked by bipedalism from which several lineages emerged. Those lineages included the Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and possibly the Gigantopithecus lines. From these groups a hominid lineage emerged that was marked by a large increase in brain size and mental ability, which enabled the invention of culture. According to Heberer, in the Villafranchian period this successful lineage reached another adaptive plateau that produced several lineages of euhominids (true human tool-makers) during the Pleistocene. When examining the existing hominid fossil record from the perspective of these three phases of human evolution, Heberer argued that the australopithecines should be considered “prehominids.” The reason for this was because he doubted that the australopithecines made tools and because they were probably not the actual group of hominids from which the euhominids had evolved, but rather represented a good model of what the true direct ancestors of euhominids were like.

Scientific opinion about the australopithecines was also undergoing significant change in the 1950s and 1960s. Heberer (1961b) noted that the australopithecines would not be considered “human” if judged by brain size, but he does consider them to be human because of the evidence for their use of tools. Since they lacked the anatomical features that would allow them to escape from or defend themselves against predators, it was reasonable in his view to infer that the australopithecines must have been tool-users. However, like most other paleoanthropologists, he was uncertain whether they were tool-makers. Heberer suggested that hominids at the subhuman phase must have used natural objects as tools, but he did not think they were tool-makers. He agreed with the argument, presented by English paleontologist Kenneth Oakley in the book Man the Tool-Maker (1956), that hominids can only be defined as having reached the “human phase” on the basis of archaeological evidence. Humans are tool-makers and so the beginning of the “human phase” of human evolution is marked by tool-making. Therefore, Heberer argued, the passage from the animal-human transition field phase to the human phase would be indicated archaeologically, not anatomically. In another paper, Heberer (1965a) argued that the mental abilities of the australopithecines should not be judged from the size of their brains. But the artifacts associated with them indicated that they were “human.”

Heberer closely followed the discoveries of new ape fossils that occurred after World War II and he published extensively on primate evolution, ape phylogeny, and their relationship to hominid phylogeny. Prior to the discovery of these fossils, anthropologists had to rely on comparative morphology and physiology to propose speculative phylogenies for the apes and hominids. These new fossils offered important information for understanding primate evolution, but Heberer stressed that despite all the new available fossil material more fossil evidence was still needed and thus scientists needed to continue using comparative morphology and physiology when reconstructing primate evolution. He was very interested in the ape fossils collected between 1947 and 1950 during the British-Kenya Miocene Expeditions, as well as the Proconsul africanus fossils that Louis and Mary Leakey found on Rusinga Island, in Lake Victoria, in 1951. He relied on the monograph on these fossils written by Wilfrid LeGros Clark and Louis Leakey (1951) and the studies of the Proconsul africanus specimens conducted by John Napier and Peter Davis (1959). Napier even sent him photographs of the Proconsul fossils.

Heberer also took great interest in the work of Swiss paleontologist Johannes Hürzeler, who studied the fossils of a Late Miocene ape called Oreopithecus (Heberer 1952b). A large number of Oreopithecus specimens had been discovered in Italy between 1862 and 1907 and during the 1950s Hürzeler published a number of papers analyzing the fossils and arguing that Oreopithecus was a hominid and not an ape. A nearly complete Oreopithecus skeleton that Hürzeler and Italian paleontologist Alberto Carlo Blanc discovered in 1958 seemed to support this view. Hürzeler allowed Heberer to examine the Oreopithecus fossils at the University of Basel. Heberer became convinced that Oreopithecus was a hominid because of its lack of canine-like premolars, its somewhat U-shaped jaw, and its wide hip bones. This would make Oreopithecus the first hominid definitively dated to the Tertiary (the fossils were thought to be approximately 10-12 million years old). However, Heberer did not think Oreopithecus was a direct ancestor of humans, but an early specialized extinct side branch of the human lineage. He thought that by that geologic period the hominid lineage had already diverged from the pongid lineage. As a consequence, Heberer created the sub-family of Oreopithecinae within the Hominidae, and so in his new scheme the Hominidae consisted of the Homininae, the Australopithecinae, and the Oreopithecinae. Heberer acknowledged that some prominent experts on fossil apes and hominids, such as Adolf Remane, Ralph von Koenigswald, and Henri Vallois did not agree that Oreopithecus was a hominid, but others such as Adolf Schultz, Jean Piveteau, and William Strauss Jr. thought it was possible.

This was a time in paleoanthropology when many paleoanthropologists still believed that the divergence of the ape and hominid lineages had occurred 15 million years ago or even earlier. During the 1960s Yale University paleontologists Elwyn Simons and David Pilbeam argued that Ramapithecus, a Miocene ape found in South Asia, was a hominid and their claims generated great interest until more complete specimens of Ramapithecus later demonstrated that they were in fact apes related to modern orangutans. Heberer expressed his belief that the Ramapithecus fossils from Asia, as well as the Kenyapithecus fossils found by Louis Leakey in east Africa, were likely Miocene hominids that may have walked upright and used tools. However, while he recognized some human-like features in Ramapithecus, he thought these had been acquired through parallel evolution and so Ramapithecus would not be a direct ancestor of humans.

The new ape and hominid fossils found since the early twentieth century were important in shaping Heberer’s ideas about the earliest, or subhuman phase, of human evolution. Like other prominent paleoanthropologists of the mid-twentieth century—such as Henri Vallois, Wilfrid Le Gros Clark, Camille Arambourg, and Louis Leakey—Heberer believed that humans had evolved from a generalized ape and had avoided passing through a specialized ape phase, as represented by chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans. He believed the divergence of the hominid lineage from the primitive pongid lineage occurred in the Early or Middle Miocene, about 25-30 million years ago, although he acknowledged that some paleoanthropologists thought this divergence had occurred in the Pliocene. He argued that the dryopithecines of the Miocene/Pliocene had begun to possess specialized characteristics of modern apes (such as their dentition and evolution toward a brachiating form of locomotion), which made it unlikely for them to be the ancestors of humans. Heberer believed instead that hominids had evolved from a quadrumanous arboreal ape that was an unspecialized pre-brachiator, and not from a specialized brachiator as some other paleoanthropologists argued. He pointed to the anatomy of the australopithecines, which were bipedal, as evidence supporting this scenario of hominid evolution since the australopithecines lacked any features of a brachiator.

A variety of theories had been proposed since the early twentieth century to explain how hominids had evolved from an apelike ancestor and the debate was still raging at mid-century. Heberer identified four competing hypotheses regarding the possible evolutionary paths that led from our early ape ancestors to modern humans: the Brachiator Hypothesis; the Pre-Brachiator Hypothesis; the Proto-catarrhine Hypothesis, and the Tarsioid Hypothesis. The Tarsoid Hypothesis was originally formulated by the English anthropologist Frederic Wood Jones in the 1920s, but Heberer noted that it was no longer taken seriously by most paleoanthropologists. Heberer thought that the current fossil evidence was inadequate to determine which of the remaining three hypotheses was the correct one. However, in his opinion, the fossil evidence, combined with what was known about the anatomy and physiology of the living primates, strongly supported the idea that the Pre-Brachiator Hypothesis was the most likely. He did not think that the ancestor of hominids had the limb proportions (long arms and short legs) of a brachiator. Heberer cited the work of Adolf Schultz and Osman Hill on primate anatomy to support this notion of hominid evolution.

Thus, for Heberer, the “subhuman phase” of hominid evolution began with a morphologically non-brachiating ancestor. As Heberer looked to the recently discovered Miocene ape fossils, he concluded that the Proconsul africanus specimens discovered by Louis Leakey approached the common ancestor of apes and hominids, since it was an arboreal ape that had not yet adopted a specialized brachiating form of locomotion. Therefore, it was the sort of creature that could have evolved into either brachiating apes or bipedal hominids. In this scenario, this non-brachiating ape then became bipedal, thus entering the “animal-human transition field,” with the australopithecines representing a good anatomical model for this phase of human evolution. Heberer agreed with South African paleoanthropologist John Robinson that two groups could be distinguished among the australopithecine fossils: the gracile Australopithecus and the robust Paranthropus. He thought Australopithecus was geologically too recent to be the direct ancestor of the euhominids (Homo erectus and later members of the genus Homo), but he thought Australopithecus possessed the general anatomical features present in our early ancestors.

Heberer published a great many papers in German, but he had an opportunity to reach an English-speaking audience when he was invited to present a paper at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology in June 1959. The topic of the symposium was “Genetics and Twentieth Century Darwinism.” Three leading advocates of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis who had led the effort to integrate the new evolutionary thinking into paleoanthropology—Ernst Mayr, Theodosius Dobzhansky, and George Gaylord Simpson—were present at the symposium. Heberer’s paper, titled “The Descent of Man and the Present Fossil Record,” provided a comprehensive summary of his ideas about human evolution. Heberer, Gottfried Kurth, and Ilse Schwidetzky (1959) published a general textbook on anthropology that same year. Soon thereafter Heberer published Die Abstammung des Menschen (1961), but one of his most influential books on human evolution was Der Ursprung des Menschen, first published in 1968 with the fourth edition appearing in 1975.

In Der Ursprung des Menschen (The Origin of Man), Heberer surveyed the existing hominid fossil record, especially recent discoveries, and presented his ideas about human evolution. He argued that hominids evolved from a pre-brachiating anthropoid ape, such as Propliopithecus. He suggested that while some apes, such as Pliopithecus, developed a pongid dentition and became brachiators inhabiting forest environments, other apes (possibly Ramapithecus) adapted to open woodland and began to walk upright and evolved a large brain. These early hominids eventually invented tools which allowed them to move into savannah environments, probably at the australopithecine stage. Heberer argued that the australopithecines should be considered hominids that had evolved to the human stage of the animal-human transition. He reiterated his argument that this animal-human transition field is marked by the advent of tool-use and thus can only be determined archaeologically and not anatomically.

Heberer closely followed Louis and Mary Leakey’s discoveries of the Zinjanthropus and Homo habilis fossils at Olduvai Gorge and he published several papers on them (Heberer 1962b; 1963; 1964). In the debates that emerged over the validity of Homo habilis, Heberer thought that Homo habilis represented the evolutionary link between Australopithecus and Homo erectus. Throughout his later career, Heberer was largely concerned with general questions of human evolution and hominid phylogeny. However, in the early 1960s he collaborated with his colleague at Göttingen University, anthropologist Gottfried Kurth, to study the Rhünda Skull. This was a fossil human cranium that was found outside the German village of Rhünda, in North Hesse, in July 1956. Eduard Jacobshagen, a professor in the Department of Anatomy and Anthropology at the University of Marburg, had examined the cranium and argued it belonged to a Neanderthal. Heberer and Kurth reconstructed the skull again and carried out fluorine and radiocarbon dating on material collected with the cranium. They suggested that the skull belonged to a Homo sapiens from the Mesolithic period (Heberer and Kurth 1960; 1962a; 1962b; 1963). Today the cranium is believed to date to the boundary between the Magdalenian and the Mesolithic (the end of the Würm glacial period and the post-glacial period), about 12,000 years ago.

Heberer was active in several institutions in the post-war years of his career. In 1956, he and biologists Adolf Remane and Wolf Herre established the Phylogenetisches Symposium, which were annual meetings on systematics and phylogeny that met in West Germany. Heberer became editor of the journal Archiv für Anthropologie in 1968. In addition to his many books and articles on paleoanthropology, evolutionary biology, and phylogenetics, Heberer also published a number of books on the history evolutionary theory. On the centenary of the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, Heberer edited a volume titled Darwin-Wallace: Dokumente zur Begründung der Abstammungslehre vor 100 Jahren, 1858/59-1958/59, which contained a collection of original publications by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. The following year, Heberer and Franz Schwanitz published Hundert Jahre Evolutionsforschung (Hundred Years of Evolutionary Research) that reviewed the history of evolutionary biology since Darwin (Heberer and Franz Schwanitz 1960). Throughout his career, Heberer had been an admirer of the German evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel, and in 1968 he published Der gerechtfertigte Haeckel (Haeckel Justified), a collection of various works by Haeckel. Heberer also wrote many popular science books on paleoanthropology and evolutionary theory. In 1971, shortly before his death, Heberer collaborated with Elly Scheffer to translate Kenneth Oakley’s Frameworks for Dating Fossil Man (1964) into German. This was at a time when new radiometric dating methods, especially the potassium-argon dating method, were revolutionizing paleoanthropological research.

Gerhard Heberer died on 13 April 1973 in Göttingen.

Selected Bibliography

“Die Spermatogenese der Copepoden. I. Die Spermatogenese der Centropagiden nebst Anhang über die Oogenese von Diaptomus castor.” Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Zoologie 123 (1924): 555-646.

Gerhard Heberer and Wolfgang Lehmann, “Die anthropologischen Arbeiten der Sunda-Expedition Rensch 1927 (Vorläufige Mitteilung).” Anthropologischer Anzeiger 5 (1928): 76-78.

“Das Abstammungsproblem des Menschen im Lichte neuerer paläontologischer Forschung.“ In R. Thurnwald (ed.), Arbeiten zur biologischen Grundlegung der Soziologie. Pp. 141-208. Leipzig: Hirschfeld, 1931.

“Die Spermatogenese der Copepoden II: Das Conjugations- und Reduktionsproblem in der Spermatogenese der calanoiden Copepoden, mit einem Anhang über die Spermatogenese von Sapphirina ovatolanceolata (Dana).” Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Zoologie 142 (1932a): 141-253.

“Untersuchungen über Bau und Funktion der Genitalorgane der Copepoden. I. Der männliche Genitalapparat der calanoiden Copepoden.” Zeitschrift für mikroskopisch-anatomische Forschung 31 (1932b): 250–424.

“Abstammungslehre und moderne Biologie.” Nationalsozialistische Monatshefte 79 (1936a): 874–890.

“Der jungsteinzeitliche Schädel von Dürrenberg.” Jahresschrift für die Vorgeschichte der sächsisch-thüringischen Länder 24 (1936b): 83–90.

“Neuere Funde zur Urgeschichte des Menschen und ihre Bedeutung für Rassenkunde und Weltanschauung.” Volk und Rasse 12 (1937): 422-27.

“Über den Rassentypus der Träger der Baalberger Kultur. Ein weiterer Beitrag zur Indogermanenfrage.” Jahresschrift für die Vorgeschichte der Sächsisch-Thüringischen Länder 29 (1938a): 105–112.

“Die mitteldeutschen Schnurkeramiker.” Veröffentlichungen der Landesanstalt für Volksheilkunde zu Halle 10 (1938b): 1-43.

“Mitteldeutschland als vorgeschichtliches Rassenzentrum.” Der Biologe 8 (1939a): 48- 53.

“Die mitteldeutschen Bandkeramiker.” Mitteldeutsche Volkheit 6 (1939b): 98–107.

“Die mitteldeutschen Bandkeramiker.” Verhandlungen der Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rassenforschung 10 (1940a): 84-90.

“Die jüngere Stammesgeschichte des Menschen.” In G. Just (ed.), Die Grundlagen der Erbbiologie des Menschen. Pp. 584-644. Berlin: Springer, 1940b.

Gerhard Heberer and Friedrich-Karl Bicker, “Der mesolithische Fund von Bottendorf a. d. Unstrut.” Anthropologischer Anzeiger 17 (1940): 266-272.

Allgemeine Phylogenetik, Paläontologie, Stammes- und Rassengeschichte. Jahreskurse für ärztliche Fortbildg 32 (1941): 18-41.

Rassengeschichtliche Forschungen im indogermanischen Urheimatgebiet. Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1943.

“Allgemeine und menschliche Abstammungslehre. Rassengenetik und Rassengeschichte.” Jahreskurse für ärztliche Fortbildg 35 (1944a): 26-42.

“Das Neandertalerproblem und die Herkunft der heutigen Menschheit.” Jenaische Zeitschrift für Medizin und Naturwissenschaft 77 (1944b): 262-289.

“Die sudafrikanischen Australopithecinen und ihre phylogenetische Bedeutung.” Zeitschrift für Naturforschung 3b (1948): 302-310.

Was heißt heute Darwinismus?. Göttingen: Musterschmidt, 1949 (2nd ed. 1960).

Gerhard Heberer and Wolfgang Lehmann, Die Inland-Malaien von Lombok und Sumbawa; anthropologische Ergebnisse der Sunda-Expedition Rensch. Göttingen: “Muster-Schmidt”, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 1950.

“Anthropologischer Streifzug durch West- und Mittel-Flores (Kleine Sunda-Inseln).” Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie 42 (1950a): 202-210.

“Das Prasapiens-Problem.” In: H. Gruneberg and W. Ulrich (eds.), Moderne Biologie: Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag von Hans Nachtsheim. Pp. 131-162. Berlin: F. W. Peters, 1950b.

Neue Ergebnisse der menschlichen Abstammungslehre. Ein Forschungsbericht. Göttingen: Musterschmidt, 1951a.

“Der phylogenetische Ort des Menschen.” Studium generale 4 (1951b): 1-14.

“Grundlinien in der pleistozänen Entfaltungsgeschichte der Euhomininen.” Quartär 5 (1951c): 50-78.

“Fortschritte in der Erforschung der Phylogenie der Hominoidea.” Ergebnisse der Anatomie und Entwicklungsgeschichte 34 (1952a): 499–637.

“Oreopithecus bambolii Gervais und die Frage der Herkunft der Cercopithecoidea.” Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie 44 (1952b): 101-107.

“Die präpleistozäne Geschichte der Hominiden.” Homo 3 (1952c): 97-101.

“Die geographische Verbreitung der fossilen Hominiden (außer Eusapiens) nach neuer Gruppierung.” Naturwissenschaften 42 (1955): 85-90.

“Fortschritt und Richtung in der phylogenetischen Entwicklung.” Studium generale 9 (1956): 180-192.

“Die Fossilgeschichte der Hominoidea.” In H. Hofer, A. H. Schultz and D. Starck (eds.), Primatologia: Handbuch der Primatenkunde. Pp. 379-560. Basel: S. Karger, 1956.

“Das Tier-Mensch-Übergangsfeld.” Studium generale 11 (1958): 341–352.

“Die subhumane Abstammungsgeschichte des Menschen.” In G. Heberer (ed.), Die Evolution der Organismen: Ergebnisse und Probleme der Abstammungslehre. 2nd ed., pp. 1110-1142. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer, 1959a.

“The Descent of Man and the Present Fossil Record” Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology 24 (1959b): 235-244.

Gerhard Heberer, Gottfried Kurth, and Ilse Schwidetzky, Anthropologie. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Bücherei, 1959.

G. Heberer and Franz Schwanitz (eds.), Hundert Jahre Evolutionsforschung. Das wissenschaftliche Vermächtnis Charles Darwins. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer, 1960.

“Grundlinien im modernen Bild der Abstammungsgeschichte des Menschen.” Biologisches Jahresheft des Verbandes Deutscher Biologen e. V. Iserlohn (1960a): 59-78.

“Älteste Menschheit in Afrika.” Natur und Volk 90 (1960b): 309-321.

“Zinjanthropus boisei und der Status der Prähomininen (Australopithecinae).” Zoologische Jahrbücher Abteilung Systematik, Ökologie und Geographie der Tiere 88 (1960c): 91-106.

Gerhard Heberer and Gottfried Kurth, “Über den Typus des pleistozänen Schädels von Rhünda (Hessen).” Homo 11 (1960): 216-220.

Die Abstammung des Menschen. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Athenaion 1961a.

“Die Herkunft der Menschheit.” In Golo Mann (ed.), Propyläen-Weltgeschichte: Eine Universalgeschichte. Vol. 1: Vorgeschichte; Frühe Hochkulturen. Pp. 87-153. Berlin: Propyläen-Verl., 1961b.

“Werkzeug-und Gerätegebrauch bei Frühhominiden.” Acta Psychologica 19 (1961): 179-180.

“The Subhuman Evolutionary History of Man.” In William W. Howells (ed.), Ideas on Human Evolution. Pp. 203-214. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1962a.

“Die Oldoway (Olduvai)-Schlucht (Tanganyika) als Fundort fossiler Hominiden.” Bibliotheca Primatologica 1 (1962b): 103-119.

Gerhard Heberer and Gottfried Kurth, “Fundumstände, relative Datierung und Typus des oberpleistozänen Schädels von Rhünda (Hessen).” Anthropologie 1 (1962a): 23-27.

Gerhard Heberer and Gottfried Kurth, “Das Ende eines “Neandertalers.” Homo 13 (1962b): 152-161.

“Über einen neuen archanthropinen Typus aus der Oldoway-Schlucht.” Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie 53 (1963): 171-177.

Gerhard Heberer and Gottfried Kurth, “Bemerkungen zu ‘Das Alter des Schädels von Rhünda. III’.” E&G Quaternary Science Journal 14 (1963): 104-106.

“Homo habilis – eine neue Menschenform aus der Oldoway-Schlucht?” Umschau (1964): 685-686.

“Über den systematischen Ort und den physisch-psychischen Status der Australopithecinen.” In G. Heberer (ed.), Menschliche Abstammungslehre: Fortschritte der “Anthropogenie” 1863-1964. Pp. 310-356. Stuttgart: Fischer, 1965a.

“Zur Geschichte der Evolutionstheorie besonders in ihrer Anwendung auf den Menschen.” In G. Heberer (ed.), Menschliche Abstammungslehre: Fortschritte der “Anthropogenie” 1863-1964. Pp. 1-19. Stuttgart: G. Fischer, 1965b.

“Die Abstammung des Menschen.” In Ludwig von Bertalanffy and Fritz Gessner (eds.), Handbuch der Biologie. Vol. 9, pp. 245-328. Konstanz: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Athenaion, 1965c.

“Über die osteodontokeratische “Kultur” der Australopithecinen.” Quartär 17 (1966): 21-50.

Steinzeit und frühe Stadtkultur. Berlin: Staatliche Museen, Generalverwaltung, 1966.

Der gerechtfertigte Haeckel. Einblick in seine Schriften aus Anlass des Erscheinens seines Hauptwerkes ‘Generelle Morphologie der Organismen’ vor 100 Jahren. Stuttgart: Verlag G. Fischer, 1968.

Der Ursprung des Menschen. Unser gegenwärtiger Wissensstand. Stuttgart: G. Fischer, 1968; (4th edition 1975).

Homo, unsere Ab- und Zukunft: Herkunft und Entwicklung des Menschen aus der Sicht der aktuellen Anthropologie. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1968.

“Die Evolution des Menschen 1.” Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 8 (1970): 126-139.

Moderne Anthropologie: Eine naturwissenschaftliche Menschheitsgeschichte. Reinbek: Rowohlt, 1973.

“Die subhumane Abstammungsgeschichte der Menschen.” In G. Heberer (ed.), Die Evolution der Organismen: Ergebnisse und Probleme der Abstammungslehre. Vol. 3, pp. 132-170. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer, 1974.

Vorgeschichte, frühe Hochkulturen. Frankfurt/M., Berlin, Vienna: Ullstein, 1976.

“The Evolution of Man.” In G. Altner (ed.), The Human Creature. Pp. 1-23. London: Allen and Unwin, 1974.

“Darwins Urteil über die abstammungsgeschichtliche Herkunft des Menschen und die heutige paläoanthropologische Forschung.” In G. Altner (ed.), Der Darwinismus. Die Geschichte einer Theorie. Pp 374–412. Darmstadt: Wiss. Buchgesellschaft, 1981.

Other Sources Cited

Wilfrid LeGros Clark and Louis Leakey, “The Miocene Hominoidea of East Africa.” Fossil Mammals of Africa 1 (1951): 1-117.

John Napier and Peter Davis, “The Forelimb Skeleton and Associated Remains of Proconsul africanus.” Fossil Mammals of Africa 16 (1959): 1-69.

Secondary Sources

Lehmann, “G. Heberer zum 70. Geburtstag.” Anthropologischer Anzeiger 33 (1972): 293-294.

Uwe Hossfeld, Gerhard Heberer (1901-1973) Sein Beitrag zur Biologie im 20. Jahrhundert. Berlin: VWB-Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung, 1997.

Uwe Hossfeld, Geschichte der biologischen Anthropologie in Deutschland. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005.

Uwe Hoßfeld and Thomas Junker, “Anthropologie und synthetischer Darwinismus im Dritten Reich: ‘Die Evolution der Organismen’ (1943).” Anthropologischer Anzeiger 61 (2003): 85-114.

Olivier Rieppel, Phylogenetic Systematics: Haeckel to Hennig. (Chapter 7). Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis, 2016.