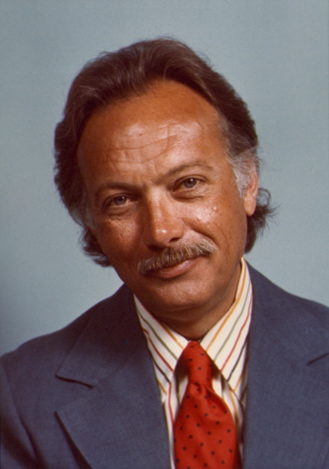

Francis Clark Howell (1925–2007)

Matthew Goodrum

Francis Clark Howell (more commonly F. Clark Howell) was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on 27 November 1925 but spent his early years on a farm in Kansas and attended a one-room schoolhouse near Topeka. His family subsequently moved to Nebraska, Indiana, and finally Wisconsin. He became interested in human prehistory and human evolution by reading Henry Fairfield Osborn’s Men of the Old Stone Age (1916) and William Howell’s Mankind so Far (1944). Howell graduated from high school in 1943 and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, from February 1944 to May 1946 in the Pacific. After being discharged, he spent several weeks at the American Museum of Natural History in August 1946 where he met the German paleoanthropologist Franz Weidenreich, whom he had corresponded with during his last year in high school. On this occasion, Weidenreich introduced Howell to the American paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson and the German paleontologist Ralph von Koenigswald, who happened to be in New York. Weidenreich had supervised excavations at the Homo erectus site of Zhoukoudian, in China, before the war and von Koenigswald had discovered Homo erectus fossils in Indonesia. Howell’s interactions with Weidenreich cemented his commitment to become a paleoanthropologist.

With support from the G.I. Bill of Rights, Howell enrolled at the University of Chicago in 1947 where he studied anthropology with Sherwood Washburn, who had just joined the department. Washburn was beginning to transform paleoanthropology through his New Physical Anthropology, which rejected the focus on racial classification that had characterized earlier physical anthropology and instead emphasized the importance of evolutionary biology and population genetics in understanding human evolution and variation among human populations. Howell also studied archaeology with Robert Braidwood, anatomy with Wilton Krogman, and paleontology with Everett Olson. As a result, Howell gained a firm foundation in human skeletal anatomy, archaeology, and mammalian paleontology. During his years at Chicago, Howell was influenced by the Spring Seminar Series organized by Sherwood Washburn, which convinced Howell of the importance of the relationship between evolutionary biology, paleontology, and ecology. He also attended the Cold Spring Harbor symposium on “The Origin and Evolution of Man” where Ernst Mayr, Theodosius Dobzhansky, George Gaylord Simpson, and other leading biologists and anthropologists argued for the need to integrate the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis into paleoanthropology. During 1953 Howell traveled to London and Paris to inspect Neanderthal specimens and while in Paris he befriended French paleoanthropologist Henri-Victor Vallois. Howell returned to Europe in 1956 to inspect Neanderthal specimens from collections throughout the continent and to attend the Neanderthal Centenary conference held in Düsseldorf, which reinforced a multidisciplinary approach to paleoanthropological research.

Howell received his bachelor’s degree in anthropology in 1949. He continued his graduate studies at the University of Chicago where he completed his Master’s degree in 1951, with a thesis on the Solo hominids found in Indonesia, and his Ph.D. in 1953. His dissertation, titled Cranial Base Structure in Man, discussed the bone structure of the skull base in humans. While still a graduate student, Howell published several important papers on the Neanderthals. These were “The Place of Neanderthal Man in Human Evolution” (1951), “Pleistocene Glacial Ecology and the Evolution of ‘Classic Neanderthal’ Man” (1952), and “The Evolutionary Significance of Variation and Varieties of ‘Neanderthal’ Man” (1957). In these papers, Howell synthesized what was known about the Neanderthals, and he brought the ideas of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis into the interpretation of them. He identified an older Generalized Neanderthal group dating from the Riss-Würm interglacial period that was anatomically more similar to modern humans. This population was followed by a later cold weather adapted “classic Neanderthal” group in which some features of the earlier Neanderthals were modified and exaggerated, especially in Western Europe. He correlated this exaggeration with genetic isolation during the last glacial period (Würm). He also argued that it was unlikely the Neanderthals were the direct ancestors of modern Europeans.

After completing his graduate studies, Howell worked as an anatomy instructor in the School of Medicine at Washington University, in St. Louis, Missouri, from 1953 to 1955. There he had the opportunity to work closely with anatomist Mildred Trotter, who was one of the founding members of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. It was while he was at Washington University that Howell married Betty Tomsen, who worked as a nurse. Over the many years of their partnership she would often accompany him on expeditions and often assisted with labeling, cleaning, and cataloguing specimens. Howell’s first experience with archaeological fieldwork came in 1953 when he assisted American Paleolithic archaeologist Hallam Movius with a test excavation of the Abri Pataud rock shelter in France. While there he became friends with French archaeologist François Bordes. He also made his first trip to Africa in 1954, where he met Louis and Mary Leakey as well as Raymond Dart. The Department of Anthropology at the University of Chicago hired Howell as a professor in 1955 (he became a full professor in 1962) and he remained there until 1970.

From 1957 to 1958, Howell conducted excavations at Isimila, in Tanganyika (now Tanzania), with Glen Cole and Maxine Kleindienst. There they recovered Acheulean hand-axes along with animal bones dated to approximately 260,000 years ago. Howell made a preliminary survey of the Omo River basin in southwestern Ethiopia in 1959, but confusion over collecting permissions led Ethiopian customs officials to confiscate the specimens he had collected, and this proved to be a severe setback. As a result, he did not return to the Omo for several years. However, Howell did attend the fourth Pan-African Congress on Prehistory and Quaternary Studies, held in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1959 and was fortunate enough to be in Nairobi, Kenya, when Mary Leakey discovered the Zinjanthropus (now Paranthropus boisei) fossils that same year.

It was during the 1959 Pan-African Congress on Prehistory that the Spanish archaeologist Lluís Pericot, of the University of Barcelona, interested Howell and French archaeologist Pierre Biberson, of the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of the Man) in Paris, in the excavations carried out by the Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa (Marquis of Cerralbo) at the site of Torralba, in Spain, from 1909 to 1913. Howell visited the sites of Torralba and Ambrona in 1960 and organized an international multidisciplinary team to conduct excavations at these sites from 1961 to 1963 and again in 1980, 1981 and 1983. The 1980s excavations were co-directed with Leslie Gordon Freeman, of the University of Chicago, and Martín Almagro Basch, director of the Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España (National Archaeological Museum of Spain). They recovered about seven hundred Acheulean stone tools and more than two thousand animal fossils from Torralba and more than four thousand Acheulean stone tools and several thousand fossils from Ambrona, which are dated to between 300,000 to 400,000 years old (Howell, Butzer, and Aguirre 1962). At Torralba the researchers found what they interpreted to be evidence that hominids (perhaps Homo erectus) hunted game, including elephants, by lighting fires and herding animals into swamps, where they were killed and butchered. This interpretation is now questioned. No hominid fossils were found at either site, however, so the identification of the makers is unclear. Howell’s decision to assemble a multidisciplinary team from the very beginning of the research project served as an important model for the Omo expedition later.

Howell spent the 1964-1965 academic year, during the interim after his field research at Torralba and Ambrona, as a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley where he taught the courses of Theodore McCown, who was going on leave. McCown had assisted British anatomist Arthur Keith in the description of the hominid fossils discovered in the caves of Skhūl and Tabūn, at Mount Carmel in Palestine. When McCown died in 1969, the university invited Howell to join the faculty. Howell accepted the offer and was a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley from 1970 until he retired in 1991. At Berkeley he joined a group of prominent colleagues that included his former mentor Sherwood Washburn, as well as Paleolithic archaeologists John Desmond Clark and Glynn Isaac, and later paleoanthropologist Tim White. Also at Berkeley at this time were biochemist Allan Wilson, who did groundbreaking work in molecular anthropology, and Garniss Curtis, who was one of the geochemists who developed the potassium-argon dating method that proved so crucial for establishing dates for hominid fossil sites.

Howell is best known for his work in the Omo River basin, in Ethiopia. French paleontologist Camille Arambourg spent about eight months exploring the Omo basin in 1932 and 1933 where he recovered numerous animal fossils. Kenyan anthropologist Louis Leakey, already known for his excavations at Olduvai Gorge, met with Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie in 1966 to discuss the possibility of an expedition to the Omo basin. The result was that Arambourg, Leakey, and Howell organized a joint French-Kenyan-American expedition to explore the Plio-Pleistocene deposits of the lower Omo River basin. The International Omo Research Expedition conducted work for eight successive field seasons from 1967 to 1973. The Kenyan team, led by Richard Leakey due to Louis’ bad health, left the project in 1968. After the death of Arambourg in November 1969, Yves Coppens led the French contingent. The International Omo Research Expedition was unprecedented in terms of scope, scale, and expense. Its primary sources of funding were the National Science Foundation, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), and the National Geographic Society. From the very beginning, Howell planned for a large, multidisciplinary group of scientists in the American contingent that would study the geology, geochronology, paleontology, archaeology, and paleoanthropology of the site as well as the environment and climate prevailing at the time the deposits were forming.

The International Omo Research Expedition proved immensely significant for several reasons. The many river sediment and volcanic layers as well as animal fossils in the Shungura and Usno Formations combined with the newly developed potassium-argon (K-Ar) and magnetostratigraphic dating methods allowed Howell to develop a detailed stratigraphic sequence that was important for the precise dating of the various deposits. Already in 1959 Howell had recognized the potential of the potassium-argon dating method that was being developed by Garniss Curtis and Jack Evernden. The International Omo Research Expedition’s most important contribution was probably to establish the detailed course of faunal change, especially in mammal species, in eastern Africa between roughly 3.6 and 1 million years ago. The study of fossil pigs by paleontologist Basil Cooke was particularly important because the many pig species could be dated and since these species frequently replaced one another pig fossils in the basin could be used as a chronological marker for other deposits that could not be dated using other methods. This work had significant implications for what came to be called the KBS tuff controversy. The KBS tuff was a layer of volcanic material in the deposits along Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana), in Kenya, where the researchers of the Koobi Fora Research Project, led by Richard Leakey, were searching for hominid fossils. Potassium-argon dating of the tuff returned a date of 2.6 million years, but the animal fossils found in these deposits were inconsistent with this date. For several years in the early 1970s, paleoanthropologists were divided by disagreement over the dating of the tuff. Clark was one of the early skeptical voices regarding the KBS dates and outlined his views during the 1973 Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research meeting in Nairobi. In the end, careful biostratigraphic analysis of the sort done by Howell, Basil Cooke, and geologist Frank Brown in the Omo basin was instrumental in resolving the dispute.

In addition to working out the stratigraphy, dating, and identification of animal fossils, the International Omo Research Expedition also discovered hominid fossils, although most of them were only small fragments. The hominid fossils included mandibles, parts of crania, and many isolated teeth. Howell published several reports, often in collaboration with Yves Coppens, on the hominid fossils from the Omo basin (Howell 1969; Howell and Coppens 1974; Howell and Coppens 1976; Howell 1978). After examining these fossils, Howell argued that they belonged to four species (Australopithecus boisie, Australopithecus africanus, Homo habilis, and Homo erectus), and he was able to arrange them chronologically, which offered possible new insights into their phylogenetic relationships (Howell and Coppens 1976). The expedition also found stone tools which dated to more than 2.3 million years ago. Along with the papers describing the hominid fossils from Omo, Coppens and Clark oversaw the publication of a monumental three volume monograph, Les faunes Plio-Pléistocènes de la basse vallée de l’Omo (Ethiopie) (The Plio-Pleistocene Fauna of the Lower Omo Valley), on the animal fossils found during the course of their work there. Unfortunately, a change in the Ethiopian government brought work in the Omo basin to a close in 1974.

While the analysis of the material from the Omo basin continued, Howell also became involved in a number of other activities. He led the first American Paleoanthropology Delegation to the People’s Republic of China in 1975. President Richard Nixon’s historic trip to China not only opened political contacts with the country, but it also created opportunities to reestablish links between American and Chinese scientists. The American Paleoanthropology Delegation was part of an exchange program operated by the Committee on Scholarly Communication with the People’s Republic of China. This committee was founded jointly by the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Social Science Research Council. From 15 May to 14 June 1975, the delegation met Chinese paleoanthropologists, visited the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, and traveled to sites such as Zhoukoudian (where the Peking Man fossils were found). A decade later, from late 1987 to early 1988, Howell returned to China to take part in a tour of Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene fossil deposits and to examine the vertebrate fossil collection of the Yunnan Provincial Museum in Yunnan, China.

Throughout his career, Howell participated in the meetings sponsored by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, and he helped to organize several influential symposia. Howell and Italian paleontologist Alberto Carlo Blanc co-organized the symposium on “Early Man and Pleistocene Stratigraphy in the Circum-Mediterranean Region” that was held at Burg Wartenstein, Austria, in July 1960. The papers were subsequently published in a special issue of the journal Quaternaria in 1962. The following year Howell co-organized a symposium with French ecologist François Bourlière on “African Ecology and Human Evolution.” This influential symposium, held at Burg Wartenstein in July 1961, brought together archaeologists, paleoanthropologists, geologists, and primatologists to discuss a synthetic approach for studying hominids within their ecological context. This meeting was also one of the first attempts to integrate evidence from Northern, Eastern, and Southern Africa. The symposium led to the publication of African Ecology and Human Evolution (Howell and Bourlière 1963).

But perhaps the most important of the Wenner-Gren meeting that Howell helped organize was the symposium on the “Stratigraphy, Paleoecology, and Evolution in the Lake Rudolf Basin.” It was co-organized by Howell, Yves Coppens, Glynn Isaac, and Richard Leakey and was sponsored by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research and the National Geographic Society. Held in Nairobi, Kenya, in September 1973, it brought together the scientists from the three research groups working at Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana) and the Omo River basin. The papers focused on the geology, paleontology, ecology, and archaeology of the deposits containing hominid remains at these sites. It avoided the debates, rampant at the time, over hominid taxonomy and phylogeny. A significant part of the symposium was devoted to correlating the stratigraphy, animal fossils, and radiometric dates of the Omo basin deposits with those from Koobi Fora along Lake Turkana. This was all connected to the KBS tuff controversy, and the symposium helped to finally resolve this problem. The papers were published in Earliest Man and Environments in the Lake Rudolf Basin: Stratigraphy, Paleoecology, and Evolution (1976).

From 1988 to 1989, Howell and Güven Arsebük, professor of anthropology at Istanbul University, led a joint Turkish-American project that conducted extensive excavations of the Paleolithic deposits in Yanmburgaz Cave, located just west of Istanbul in Turkey. These excavations unearthed approximately 1700 Lower Paleolithic stone and bone artifacts as well as animal fossils dating from the Middle Pleistocene. From 1993 to 1994, Howell joined a team of researchers from the University of California, Berkeley in a joint project with Turkish anthropologist Erksin Güleç and others from the University of Ankara, as well as scientists from the Turkish Geological Service, to excavate the sediments at Dursunlu (Konya), on the Anatolian Plateau in Turkey. These investigations yielded animal fossils and quartz artifacts that date to at least 780,000 years ago.

Howell is considered to be one of the architects of modern paleoanthropology. He believed paleoanthropology should be a science that integrated archaeology, geology, biological anthropology, ecology, evolutionary biology, primatology, and ethnography. He was a strong advocate for making paleoanthropological research a multidisciplinary collaborative endeavor that brought together experts from different disciplines. His colleagues repeatedly note that he helped transform paleoanthropology from a discipline focused on discovering hominid fossils to one that investigates the paleontology, geology, geochronology, archaeology, and paleoenvironment of a site. He was an expert on the hominid fossil record as well as Pleistocene stratigraphy and its animal fossil record. In addition to his work in paleoanthropology, Howell also conducted research on the evolution of carnivores and of Old World monkeys.

His major publications cover a wide range of subjects. Beyond his early publications on the Neanderthals and the many papers on the Omo basin, Howell published papers on the timing and circumstances of the Pleistocene occupation of Europe by early humans (Howell 1959a). In this context, he examined the Villafranchian fauna of Europe as well as the Acheulean artifacts found in Europe. Howell contributed the immensely useful chapter on the “Hominidae” in Evolution of African Mammals (1978) edited by V. J. Maglio and H. B. S. Cooke, which reviewed the African hominid fossil record. He also wrote the chapter on “Evolution of Hominidae in Africa” that appeared in the first volume of the Cambridge History of Africa (1982). However, his most widely read work was Early Man (1965), a book written for a general audience and published by Time/Life Books as part of their Life Nature Library series. This was one of the first general summaries of modern paleoanthropology and it reached a very wide readership. Howell also served as senior scientific adviser for the television documentary The Man-Hunters, which featured his fieldwork in the Omo basin.

In addition to his research and publications, Howell was influential in many of the central institutions of American paleoanthropology, and he played a role in the creation of several new institutions. Howell was instrumental in the creation of the Leakey Foundation (officially the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation for Research Related to Man’s Origins, Behavior & Survival). The Leakey Foundation was formed in 1968 by supporters of Louis Leakey’s research in order to secure funding for human origins research of all kinds. As a member of the Foundation, Howell served as Science Advisor, as chairman of the Science and Grants Committee, and as a trustee. As chairman of the Science and Grants Committee he steered funding to a broad range of disciplines beyond just archaeology and physical anthropology, including projects on hunter-gatherers and on non-human primates. It was partially through Howell’s encouragement that the Leakey Foundation supported Jane Goodall’s work on chimpanzees in what is now the Gombe Stream National Park (in Tanzania), Biruté Galdikas’ studies of orangutans in Indonesia, and Diane Fossey research on gorillas in Rwanda.

Howell founded the Laboratory for Human Evolutionary Studies in 1970, shortly after arriving at the University of California, Berkeley. It was renamed the Human Evolution Research Center in 1995, and for more than thirty years, Howell co-managed it with his colleague Tim White. He was also involved in establishing the Berkeley Geochronology Center. Howell also played a significant role in the creation of the Institute for Human Origins in 1981, which is now located at Arizona State University. He also encouraged the founding of the Stone Age Institute by Nicholas Toth, Kathy Schick, and Henry Corning in Bloomington, Indiana, in 2000. Howell was active in a number of other scientific institutions. He served as a trustee of the California Academy of Sciences from 1976 until 1990, and held the office of president from 1980 to 1982. The Academy awarded him its Fellows Medal in 1990. Howell was a member of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, of the American Anthropological Association, and of the Deutsche Quartärvereinigung (German Quaternary Association). During the 1960s, he was involved in the Hominid Casting Program of the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, which produced and distributed high-quality casts of significant hominid fossils. Howell also served on the advisory council of the National Center for Science Education beginning in 2013.

Howell received many awards and honors during his career and was elected to several prestigious organizations. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1972, and he served as an adviser to the National Science Foundation. He was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1974 and of the American Philosophical Society in 1975. He was also a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He was named an honorary fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland; a Foreign Associate of the Royal Society of South Africa in 1985; and a Foreign Associate Member of the Académie des Sciences in 1989. He received the Charles Darwin Award for lifetime achievement from the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. In 1998 the Leakey Foundation awarded him the Leakey Prize, and he received the Franklin L. Burr Award of the National Geographic Society in 1993. Howell was the Distinguished Lecturer in 1977 at the 76th annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association, where he presented a paper titled “Understanding Human Origin: Problems and Prospects.” The

University of Chicago awarded him with an honorary doctorate in 1992. Howell’s name is also immortalized taxonomically. At least seven extinct species are named for him. The species name howelli is attached to two mollusks, two ancestral species of civet cats, one hyena, an extinct species of antelope, and a primate of the loris family.

In 2003, Howell and Tim White formed the Revealing Hominid Origins Initiative (RHOI). This was an umbrella program that supported the collection, curation, and study of fossils dating mainly from the period, 5 to 7 million years ago, when humans and chimpanzees last shared a common ancestor. The RHOI was the largest paleoanthropology project ever funded by the National Science Foundation, and by the time the project ended in 2010, it had underwritten thirty-six paleontological projects involving more than fifty scientists in fifteen countries, and it generated three hundred and ninety-six publications. Howell had a profound influence on paleoanthropology through his research but also as a mentor to his students. He trained many students while at Chicago and Berkeley, including an entire generation of young Ethiopian paleontologists who earned their doctorates under him. In February 2007, one month before his death, Howell sat down for interviews with Samuel Redman of the Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center. He continued to work in his laboratory as emeritus professor until his illness forced him to stop. F. Clark Howell died of metastatic lung cancer on 10 March 2007 at his home in Berkeley, California.

Selected Bibliography

“The Place of Neanderthal Man in Human Evolution.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 9 (1951): 379-416.

“Pleistocene Glacial Ecology and the Evolution of ‘Classic Neanderthal’ Man.” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 8 (1952): 337-410.

“The Evolutionary Significance of Variation and Varieties of ‘Neanderthal’ Man.” Quarterly Review of Biology 32 (1957): 330-347.

“The Age of the Australopithecines of Southern Africa.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 13 (1955): 635-661.

“The Evolutionary Significance of Variation and Varieties of ‘Neanderthal’ Man.” Quarterly Review of Biology 32 (1957): 330-347.

“The Villafranchian and Human Origins.” Science 130 (1959a): 831-844.

“Upper Pleistocene Stratigraphy and Early Man in the Levant.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 103 (1959b): 1-65.

“European and Northwest African Middle Pleistocene Hominids.” Current Anthropology 1 (1960): 195-232.

F. Clark Howell, Karl Butzer, and Emiliano Aguirre, Noticia preliminar sobre el emplazamiento acheuleuse de Torralba, Soria. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 1962.

F.C. Howell and F. Bourlière, Eds. African Ecology and Human Evolution Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology, No. 36 (Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research) Chicago: Aldine, 1963.

“Observations on the Earlier Phases of the European Lower Paleolithic.” American Anthropologist 68 (1966): 88-201.

“Recent Advances in Human Evolutionary Studies.” Quarterly Review of Biology 42 (1967): 471-513.

“Remains of Hominidae from Pliocene-Pleistocene Formations in the Lower Omo Basin, Ethiopia.” Nature 223 (1969): 1234-9.

F. Clark Howell and Yves Coppens, “Inventory of Remains of Hominidae from Pliocene/Pleistocene Formations of the Lower Omo Basin, Ethiopia (1967–1972).” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 40 (1974): 1-16.

F. Clark Howell and B. A. Wood, “Early Hominid Ulna from the Omo Basin, Ethiopia.” Nature 249 (1974): 174-176.

F. Clark Howell and Yves Coppens, “An Overview of Hominidae from the Omo Succession, Ethiopia.” In Y. Coppens, F. C. Howell, G. Isaac, and R. Leakey (eds.). Earliest Man and Environments in the Lake Rudolf Basin. Stratigraphy, Paleo-ecology and Evolution. Pp. 522–532. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

Yves Coppens, F. Clark Howell, Glynn Isaac, and Richard Leakey, Earliest Man and Environments in the Lake Rudolf Basin. Stratigraphy, Paleoecology, and Evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

N. T. Boaz and F. C. Howell, “A Gracile Hominid Cranium from Upper Member G of the Shungura Formation, Ethiopia.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 46 (1977): 93-108.

“Overview of the Pliocene and Earlier Pleistocene of the Lower Omo Basin, Southern Ethiopia.” In Clifford Jolly (ed.), Early Hominids of Africa. Pp. 85-130. London: Duckworth, 1978.

“Hominidae.” In V. J. Maglio and H. B. S. Cooke (eds.). Evolution of African Mammals. Pp. 154-248. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978.

Y. Rak, and F. C. Howell, “Cranium of a Juvenile Australopithecus boisei from the Lower Omo Basin, Ethiopia.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 48 (1978): 345-366.

“Evolution of Hominidae in Africa” in J. Desmond Clark (ed.), Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 1 From the Earliest Times to ca. 500 B.C. Pp. 70-156. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Yves Coppens and F. Clark Howell, Les Faunes Plio-Pléistocènes de la basse vallée de l’Omo (Ethiopie). 3 vols. Paris: Editions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1985, 1987, 1988.

“Overview of the Pliocene and earlier Pleistocene of the Lower Omo Basin, Southern Ethiopia.” In C. Jolly (ed.), Early Hominids of Africa. Pp. 85-130. London: Duckworth, 1978.

“Homo habilis in Detail.” Science 253 (1991): 1294-5.

“A Chronostratigraphic and Taxonomic Framework of the Origins of Modern Humans.” In M. H. Nitecki and D. V. Nitecki (eds.), Origins of Anatomically Modern Humans. Pp. 253-319. New York: Plenum Press, 1994.

“Thoughts on the Study and Interpretation of the Human Fossil Record.” In W. Meikle, F. C. Howell, and N. Jablonski (eds.), Contemporary Issues in Human Evolution. Pp. 1-45. California Academy of Sciences Memoir 21, 1996.

“Paleo-demes, Species Clades and Extinctions in the Pleistocene Hominin Record.” Journal of Anthropological Research 55 (1999): 191-243.

F. Clark Howell, Güven Arsebük, Steven L. Kuhn, Mihriban Özbasaran, Mary C. Stiner, Culture and biology at a crossroads: The Middle Pleistocene record of Yarimburgaz Cave (Thrace, Turkey). Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari, 2010.

Secondary Sources

Bernard Wood, “Obituary: Francis Clark Howell (1925-2007).” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 136 (2008): 125-127.

Tobias, Phillip V. “Francis Clark Howell Hon. FRSSAf 1925-2007.” Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 62 (2007): 44-46.

K. W. Butzer and R. G. Klein, “F. Clark Howell 1925-2007.” Journal of Archaeological Science 34 (2007): 1552-1553.

Leslie Freeman, “Francis Clark Howell (1925-2007).” American Anthropologist 110 (2008): 274-276.

Tim White, “Obituary: F. Clark Howell 1925-2007.” Nature 447(2007): 52.

Susan Anton, “Of Burnt Coffee and Pecan Pie: Recollections of F. Clark Howell on his Birthday. November 27, 1925 – March 10, 2007.” PaleoAnthropology (2007): 36-52.

Elwyn Simons, “Francis Clark Howell: November 27, 1925 – 10 March 2007.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 155 (2011): 205-209.

Richard Klein, “Francis Clark Howell.” Biographical Memoirs. National Academy of Sciences 2013.

Mary C. Stiner and Steven L. Kuhn, “Early Man: A Tribute to the Late Career of F. Clark Howell.” Journal of Human Evolution 55 (2008): 758-760.

Samuel J. Redman, “F. Clark Howell: Modernizing Physical Anthropology through Fieldwork, Science, and Collaboration.” An interview conducted by Samuel J. Redman in 2007. Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2012.