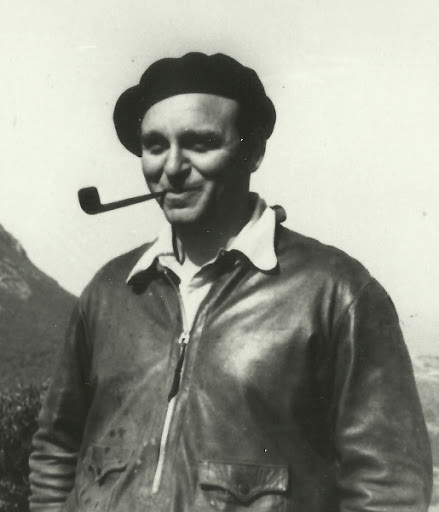

Alberto Carlo Blanc (1906–1960)

Matthew Goodrum

Alberto Carlo Blanc was born in the town of Chambery, in the Savoy region of France, on 30 July 1906. Blanc descended from an old and prominent Catholic Savoyard family. His parents were Gian Alberto Blanc and Maria Blanc (née Menotti). Gian Alberto Blanc was professor of geochemistry at the University of Rome and conducted research on Quaternary geology and paleoanthropology. Gian Alberto was known for his excavations of a cave called Grotta Romanelli, and in 1912 he and Aldobrandino Mochi, influenced by the recent establishment of the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine (Institute of Human Paleontology) in Paris, established the Comitato per le Ricerche di Paleontologia Umana in Italia. The Committee, which was formally constituted in May 1913, became the Istituto Italiano di Paleontologia Umana (Italian Institute of Human Paleontology) in 1927. Alberto Carlo’s grandfather, Alberto Blanc, was a politician and diplomat. When the Duchy of Savoy voted to become part of France with the Treaty of Turin in 1860, Alberto Blanc chose to retain Italian nationality out of loyalty to the Prince of Savoy. The Blanc family moved to Rome and was awarded the title of baron by King Victor Emmanuel II in 1873. As a child Alberto Carlo Blanc was interested in his father’s geological and paleontological pursuits, and he became particularly interested in human prehistory, ethnology, Quaternary geology, and paleoanthropology.

After graduating from secondary school in Rome, Blanc enrolled at the University of Pisa, where he completed a doctoral degree in geology in 1934, studying under the Italian geologist Giuseppe Stefanini. He remained at the University of Pisa, working first as Stefanini’s assistant (1935-1936) and then as his research assistant (1936-1938) at the university’s Institute of Geology. Stefanini had been one of the proponents of the founding of the Comitato per le Ricerche di Paleontologia Umana, and he taught a multidisciplinary natural science approach to the study of human prehistory that integrated geology, paleontology, biology, ethnology, and anthropology. Blanc spent the 1936-1937 academic year in Paris studying in the Laboratoire de Géographie Physique et Géologie Dynamique at the Sorbonne and at the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, where he interacted with the French prehistorian Henri Breuil. Henri Breuil had been a friend of Gian Alberto Blanc for years, and he became an important influence on the young Alberto Carlo. After the year in Paris Blanc returned to Pisa, but when Giuseppe Stefanini unexpectedly died in 1938, Blanc taught the course in geology for the 1938-1939 academic year. He left this position, however, to become a professor at the University of Rome (officially the Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”) in 1939, where he taught ethnology and human paleontology. Blanc received his Docenza in paleoethnology from the University of Rome in 1940. In 1957 he was appointed to the chair in paleoethnology and became director of the university’s Institute of Paleoethnology. He held these positions until his death.

Beginning from his days as a student, Blanc had become involved in geological, archaeological, and paleoanthropological research. While a student at the University of Pisa, Blanc had assisted in the excavations carried out by his father at Grotta Romanelli. In 1933 he joined his father’s excavations at Tecchia d’Equi, in Lunigiana, where they discovered stone tools and animal fossils from the Paleolithic. Blanc also initiated the first of what would become many years of investigations of the stratigraphy of the Tyrrhenian coast of Italy in order to reconstruct the changes in climate during the late Quaternary and the chronology of the glaciations in the region. He realized that the work of German geologists Albrecht Penck and Eduard Brückner on the chronology of the glaciations during the Pleistocene, which they conducted in the Alps, could not be easily or directly applied to other regions. Penck and Brückner identified four glacial periods during the Pleistocene (which they named the Gunz, Mindel, Riss, Würm), each separated by warmer interglacial periods. Since the geological evidence from the Alps could not easily be matched to the geology of Italy, Blanc attempted to correlate this sequence of glacial and interglacial periods with the changes in sea level recorded in geological features along the Italian coast. Blanc also investigated the geology along the canals dug in the Agro Pontino on the Pontine plain, focusing especially on the channel called the Canale delle Acque Alte. This allowed him, often in collaboration with University of Pisa botanist Ezio Tongiorgi, to construct a stratigraphic sequence of animal and plant fossils and Paleolithic artifacts. This research also allowed him to establish correlations between the recent geological history of the Mediterranean and that of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

Blanc’s interest in paleoanthropology also emerged early in his career. In May 1929 Duke Mario Grazioli discovered a Neanderthal cranium in the gravel pit of Sacco Pastore, which lies on the bank of the Aniene River near Rome. Blanc attended the meeting of the Società Romana di Antropologia (Roman Society of Anthropology) later that year where Sergio Sergi, professor of anthropology at the University of Rome, presented the fossil from Saccopastore to the public for the first time. It was the first Neanderthal specimen to be found in Italy and consequently it generated considerable interest. Several partial Neanderthal skeletons had been discovered in France during the previous two decades (Le Moustier in 1908; La Chapelle-aux-Saints in 1908; La Ferrassie in 1909 and 1910; La Quina in 1911), but despite these finds many questions still remained about the Neanderthals and their place in human evolution.

In July 1935, Blanc accompanied Henri Breuil on a visit to the gravel pit at Saccopastore, and to their great surprise, they found a partial Neanderthal cranium. As a result, the Istituto Italiano di Paleontologia Umana and the Institute of Anthropology at the University of Rome sponsored an excavation of the site, led by Blanc over several months in 1936. Blanc’s father Gian Alberto as well as Henri Breuil and the Chinese paleontologist Pei Wenzhong participated in the excavations, which produced extinct elephant, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus fossils along with Mousterian artifacts dating from the last interglacial (Riss-Würm) (Breuil and Blanc 1935; 1936). They sent this second Neanderthal cranium to Sergio Sergi for examination and it remains in the collections of the university (Sergi 1948). Since the Saccopastore crania were the first Neanderthals discovered in Italy they provided valuable new information about the Neanderthals and their geographical distribution in Europe. Sergi’s examination challenged French paleontologist Marcellin Boule’s reconstruction and interpretation of the Neanderthals, which had been based on the La Chapelle-aux-Saints specimen. The discovery of this Saccopastore cranium brought Blanc international recognition and began a period of collaboration with Breuil.

Blanc began examining the coastline around Mount Circeo in 1936, studying the changes in sea level in this area during the Quaternary. He was particularly interested in the way that changes in climate, environment, and glaciations affected animal and human migrations during the Paleolithic. (Blanc 1938). Blanc explored twenty-seven new caves and collected animal fossils and Paleolithic artifacts, many of them Mousterian. During his excavation of the caves on Mount Circeo, Blanc met Elena Aguet. She was the daughter of Luigi Aguet, who owned the land around the caves and whose permission Blanc needed to conduct his research. Blanc and Elena Aguet married in February 1939, and during their honeymoon, Blanc received unexpected news about the discovery of a Neanderthal cranium in a cave that is now called the Grotta Guattari, at Monte Circeo. The entrance to the cave was discovered by chance on 24 February 1939 when some workers were extracting limestone on the property of Alessandro Guattari. Guattari was the owner of a hotel near San Felice Circeo, a town south of Rome. Blanc had stayed there at times during his work at Mount Circeo. Guattari entered the cave the day after it was discovered, and he found the cranium reportedly lying in a circle of stones and animal bones. A few days later Guattari found a Neanderthal mandible. He handed the fossils over to Blanc, who recognized the bones as being Neanderthal (Blanc 1938-39; 1939a; 1939b; 1939c; 1940a; 1940b).

Blanc interpreted the placement of the cranium in a stone circle as demonstrating that the Neanderthals had rituals and religious beliefs. On the basis of damage observed on the cranium Blanc also argued that they engaged in headhunting and ritual cannibalism. Blanc sent the Circeo cranium to Sergio Sergi for examination (Sergio 1938; 1939), but the full description of the fossil was delayed by Sergi’s death in 1972, and the anatomist and anthropologist Antonio Ascenzi completed it in 1974 (Sergi 1974). Blanc and Sergi’s interpretation of the Neanderthals, based upon the Saccopastore and Circeo specimens, challenged Boule’s interpretation of them as primitive and brutish and suggested instead that they were anatomically and culturally more similar to Homo sapiens than previously believed. The Circeo skull is now in the collection of the Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico “Luigi Pigorini” in Rome.

Blanc remained in Italy during World War II and continued to pursue his research. Over three seasons (1941, 1942, and 1949) he and archaeologist Luigi Cardini excavated the rock shelter of Riparo-Mochi, at Balzi Rossi near the border with France, where they recovered Paleolithic artifacts. During these years, he also published two papers outlining his theory of ethnolysis, which he later expanded into his theory of cosmolysis. Blanc’s theory of ethnolysis sought to explain cultural change during prehistory, relating it to the diversity of ethnic groups, their geographic distribution, and their migrations and interactions, all within the context of environment and climate (Blanc 1942a). Blanc’s theory of cosmolysis applied the principles and ideas of ethnolysis to the evolution of the universe and of life (Blanc 1943a). In his ethnological writings, Blanc critiqued the German culture-historical school of archaeology and anthropology, as well as the Kulturkreise theory of diffusionists that was linked to this school. He also criticized the ideas, first proposed by the anthropologist Giuseppe Sergi and archaeologist Luigi Pigorini and promoted in the 1920s by Ugo Rellini, professor of paleoethnology at University of Rome, that a North African population had migrated into Iberia and Italy during the Upper Paleolithic (Blanc 1940c). Like most anthropologists and ethnologists of his generation, Blanc addressed the subject of human races and the origins of the races. His ethnological ideas were published in a monograph titled Origine e sviluppo dei popoli cacciatori e raccoglitori (1956), which discussed the culture of Paleolithic and Mesolithic people as well as modern hunter-gatherers.

At the end of the war, Blanc initiated several new excavations with colleagues from the Istituto Italiano di Paleontologia Umana. Blanc’s team renewed work at Mount Circeo, and in 1954 he and archaeologist Luigi Cardini discovered a partial Neanderthal mandible in the Grotta del Fossellone (Blanc 1954). Blanc once again sent this fossil to Sergio Sergi and Antonio Ascenzi for examination. Blanc and Cardini then led a team from the Istituto Italiano di Paleontologia Umana to excavate the site of Torre in Pietra from 1954 to 1957. They found animal bones as well as Mousterian and Acheulean artifacts that helped them to reconstruct the Paleolithic in Italy (Blanc 1954b). Their work also extended the Neanderthal occupation in Italy back to before the last interglacial period (Riss-Würm), earlier than previously known (about 300,000 years ago). This research prompted Blanc to argue that Neanderthal culture remained relatively unchanged over an extremely long period of time despite the fact that Neanderthal anatomy had changed. The studies of the stratigraphy, fossil fauna, and paleobotany of the region around Rome that Blanc had conducted over the course of many years led him to identify five periods associated with glaciations. He named these the Acqua-traversan, Cassian, Flaminian, Nomentanan, and Pontinian, and he correlated each of these with the alpine glacial and interglacial periods identified by Albrecht Penck (Blanc 1957).

Blanc and Luigi Cardini then turned their attention to the coastal caves along the Capo di Leuca, and while excavating the Grotta delle Tre Porte in 1958, they unearthed deposits dating from the last interglacial period (Riss-Würm) containing hearths, animal bones, and there they found a single Neanderthal tooth (Blanc 1962). During the 1950s, Blanc also became interested in Paleolithic art. In 1958 he published a monograph, Dall’astrazione all’organicità (From Abstraction to Organicity), based on his studies of prehistoric cave paintings and art. Blanc argued that abstract art preceded naturalistic art while also arguing that both are due to innate tendencies of the human mind, even though one or the other form may dominate for certain periods of time. His interpretation of prehistoric art was influenced by Henri Breuil’s magical-religious theory of cave paintings. In an earlier work, titled Il sacro presso i primitivi (1945), Blanc examined ethnographic material pertaining to religious beliefs and rituals from across the world and related this to paleoethnological evidence.

Blanc was active in several prominent Italian scientific institutions during his career. Probably the most important to his research was the Istituto Italiano di Paleontologia Umana. Blanc worked closely with the Institute throughout his career; many of his excavations were conducted under the auspices of the Institute, and it shaped his approach to investigating human paleontology. The Institute’s members took a multidisciplinary approach to studying human prehistory and emphasized the natural sciences over a historical or simply archaeological approach to studying human prehistory. Its members also considered the study of the climate and environment to be central to this research. The Institute’s membership included many prominent Italian scientists, as well as scientists from across Europe. Blanc served as general secretary of the Roman section of the Institute beginning in 1937. In 1945 he and Paolo Graziosi, professor of archaeology and anthropology at the University of Florence, drew up new statutes for the Institute.

Blanc served as president of the Commission on Shorelines, organized by the International Union for Quaternary Research (INQUA), from 1953-1960. He also organized and presided over the fourth meeting of the International Union for Quaternary Research, which held sessions in Rome and Pisa in 1953. This meeting was an important effort to reintegrate Italian scientists into the international community of scientists following the end of World War II and the fall of the fascist government in Italy. Blanc co-organized two symposia sponsored by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. He and American paleoanthropologist F. Clark Howell organized a symposium on “Early Man and Pleistocene Stratigraphy in the Circum-Mediterranean Region” that was held at Burg Wartenstein, Austria, in July 1960, but Blanc died two days before the symposium began. He and Luis Pericot of the University of Barcelona organized a symposium on “The Chronology of Western Mediterranean and Saharan Prehistoric Cave and Rock Shelter Art” that was also held at Burg Wartenstein, Austria, a few weeks later.

Blanc was a member of the Istituto Italiano di Antropologia (Italian Institute of Anthropology) as well as the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei (Lincean Academy). He was also active in the Società Italiana per il Progresso delle Scienze (Italian Society for the Advancement of the Sciences) and he was a member of the Comité de Perfectionnement (Improvement Committee) of the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine in Paris. In 1954 Blanc founded the journal Quaternaria, which was dedicated to the natural and cultural history of the Quaternary era, and he served as its editor until his death. He was invited to be a visiting professor at the University of Chicago and at the University of California at Berkeley in 1959. Blanc died unexpectedly on 3 July 1960 in Rome.

Selected Bibliography

A full bibliography of Blanc’s works can be found in “Pubblicazioni di Alberto Carlo Blanc,” Quaternaria 6 (1962): 13-92.

Henri Breuil and Alberto C. Blanc, “Il nuovo cranio di Homo neanderthalensis e la stratigrafia del giacimento di Saccopastore (Roma).” Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana” 54 (1935): 289-300.

Henri Breuil and Alberto C. Blanc, “Le nouveau crâne néanderthalien de Saccopastore (Rome).” L’Anthropologie 46 (1936): 1–16.

“Sulla penetrazione e diffusione in Europa ed in Italia del Paleolitico superiore in funzione della paleoclimatologia e paleografia glaciali.” Quartär 1 (1938): 1-26.

“L’uomo fossile del Monte Circeo. Un cranio neandertaliano nella Grotta Guattari a San Felice Circeo.” Rivista di Antropologia 32 (1938-39): 1-18.

“II Monte Circeo, le sue grotte paleolitiche ed il suo uomo fossile.” Bollettino della Reale Società Geografica Italiana (1939a): 485-493.

“L’uomo fossile del Circeo ed il suo ancora ignoto successore.” Scienza e Tecnica 3 (1939b): 345-353.

“L’uomo del Monte Circeo e la sua età geologica.” Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana 58 (1939c): 201-214.

“L’homme fossile du Mont Circé.” L’Anthropologie 49 (1939d): 253-264.

“Les grottes paléolitiques et l’homme fossile du Mont Circé.” Revue scientifique 78 (1940a): 21-28.

“The Fossil Man of Circe’s Mountain.” Natural History 45 (1940b): 281-287.

“Sull’origine del Paleolitico superiore d’Italia.” Razza e civiltà 1 (1940c): 489-498.

“Etnolisi—Sui fenomeni di segregazione in biologia ed in etnologia” Rivista di antropologia 33 (1942a): 5-113.

“I paleantropi di Saccopastore e del Circeo.” Quartär 4 (1942b): 1-37.

“Cosmolisi—Interpretazione genetico-storica delle entità e degli aggrupamenti biologici ed etnologici,” Rivista di antropologia 34 (1943a): 144-290.

Corso di etnologia: origine e sviluppo dei popoli cacciatori e raccoglitori. Rome: Tumminelli, 1943.

Il sacro presso i primitivi. Rome: Partenia, 1945.

“L’évolution humaine dans le cadre de la cosmolyse.” Revue de Théologie et de Philosophie 34 (1946): 49-74.

Sviluppo per lisi delle forme distinte. Rome: Partenia, 1946.

“Reperti fossili neandertaliani nella grotta del Fossellone al Monte Circeo: Circeo IV.” Quaternaria 1 (1954a): 171-175.

“Giacimento ad industria del Paleolitico inferiore (Abbevilliano superiore ed Acheulano) e fauna fossile ad Elephas a Torre in Pietra presso Roma.” Rivista di antropologia 41 (1954b): 3-11.

Origine e sviluppo dei popoli cacciatori e raccoglitori. Rome: Edizioni dell’Ateneo, 1956.

“On the Pleistocene Sequence of Rome: Paleoecologic and Archaeologic Correlations.” Quaternaria 4 (1957): 95-109.

“Torre in Pietra, Saccopastore, Monte Circeo. On the Position of the Mousterian in the Pleistocene Sequence of the Rome Area.” In G. H. R. von Koenigswald (ed.), Hundert Jahre Neanderthaler. Pp. 167-174. Koln-Graz: Bohlau-Verlag, 1958.

“Torre in Pietra, Saccopastore, Monte Circeo. La cronologia dei giacimenti e la paleografia quaternaria del Lazio.” Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana 14 (1958): 196-214.

Dall’organicità all’astrazione. Rome: De Luca Editore, 1958.

Notizie sull’operosità scientifica e didattica di Alberto Carlo Blanc. Rome: Castaldi, 1960.

“Leuca I. Il primo reperto fossile neandertaliano del Salento.” Quaternaria 5 (1962): 271-278.

Sergio Sergi, “Il cranio neandertaliano del Monte Circeo. Nota preliminare.” Rivista di antropologia 32 (1938): 19-34.

Sergio Sergi, “Il cranio neandertaliano del Monte Circeo.” Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Rendiconti Lincei 29 (1939): 672-85.

Sergio Sergi, “Il cranio del secondo paleoantropo di Saccopastore: Craniografia e craniometria.” Palaeontographia Italica 42 (1948): 4-164.

Sergio Sergi, Il cranio neandertaliano del Monte Circeo (Circeo I), (edited and with a preface by Antonio Ascenzi). Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1974.

Secondary Sources

Sergio Sergi, “Ricordo di Alberto Carlo Blanc.” Rivista di antropologia 48 (1961): 219-220.

Georges Laplace, “Alberto Carlo Blanc.” Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 58 (1961): 515-519.

F. Clark Howell, “Alberto Carlo Blanc (July 30, 1906-July 3, 1960).” Quaternaria 6 (1962): 3-9.

Gian Alberto Blanc and Maria Cristina Blanc, “Blanc, Alberto Carlo.” In Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Vol. 10, pp. 760-762. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana, 1968.

André Cailleux, “Blanc, Alberto-Carlo.” In Charles C. Gillispie (ed.), Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1, pp. 189-190. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1981.

Antonio Ascenzi, “A Short Account of the Discovery of the Mount Circeo Neandertal Cranium.” Quaternaria Nova 1 (1990-91): 69-80.

Brunetto Chiarelli and Giuseppe D’Amore, “Blanc, Alberto Carlo (1905-1960).” In Frank Spencer (ed.), History of Physical Anthropology. Vol. 2, pp. 182-183. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997.

V. S. Severino, “Da Raffaele Pettazzoni a Carlo Alberto Blanc. Una premeditata successione all’incarico di Etnologia.” Studi e materialidi storia delle religioni n. s. 28 (2004): 397-412.

Stefano Pipi, Alberto Carlo Blanc (1906-1960): crani, genetica e nuovo umanesimo. Dissertation completed at the University of Pisa, 2014.

Stefano Pipi, “‘Un’etnologia sui generis'”: Alberto Carlo Blanc.” Lares 82 (2016): 41-60.