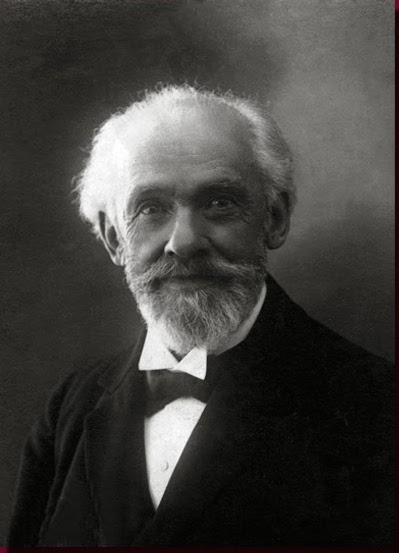

René Verneau (1852–1938)

Matthew Goodrum

René Pierre Verneau was born on 23 April 1852 in La Chapelle-sur-Loire, in central France.1 His family belonged to the provincial petty bourgeoisie. His father, René Verneau, was a farmer, and his mother was Marie Clémence Galbrun. As a boy Verneau was interested in science, collecting plants, stones, and insects as well as assembling a small chemistry laboratory. Verneau studied at the college in Saumur where he completed a Bachelors degree in 1869, and he entered the Faculty of Medicine in Paris to study medicine, but the Franco-Prussian War interrupted his studies. During the war, he served as a surgeon’s assistant to Charles Pajot, professor at the Faculty of Medicine. After the war, Verneau continued his medical studies, but his interests changed when he attended the course on prehistoric anthropology at the Sorbonne taught by Ernest-Théodore Hamy and the anthropology course of Armand de Quatrefages at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle [National Museum of Natural History]. These experiences led Verneau to decide upon a career in anthropology. The leading centers of anthropological research at this time were the Museum of Natural History, where Quatrefages held the chair of anthropology, and a group of related institutions created by Paul Broca. These included the Société d”Anthropologie de Paris [Anthropology Society of Paris] founded in 1858, the Laboratoire d’Anthropologie [Laboratory of Anthropology] created in 1867, and the École d’Anthropologie [School of Anthropology] established in 1876.

Verneau completed his degree in medicine in 1875 with a thesis on the human pelvis titled Le Bassin dans les sexes et dans les races for which he received a Lauréat of the Faculty of Medicine. That year he also became a member of the Société d’anthropologie de Paris, which put him in contact with many of France’s leading anthropologists, particularly Paul Broca. Meanwhile, Quatrefages had been so impressed with Verneau that he hired him as a prèparateur (student demonstrator) at the Museum of Natural History in 1873. Verneau’s career took an unexpected turn in 1876 when he was invited to join an expedition to the Canary Islands organized by the French government’s Ministry of Public Education. The expedition was established to gather scientific data about the archipelago of islands that lie off the west coast of Morocco. Verneau was tasked with studying the early inhabitants of the archipelago and investigating their potential relationship with the Paleolithic Cro-Magnon people whose fossil remains had been discovered in France and other parts of Europe. This inquiry was prompted by the opinion, originally proposed by Paul Broca and later promoted by Ernest-Théodore Hamy, that there were anatomical similarities between the aboriginal inhabitants of the archipelago (the Guanches) and the Cro-Magnon people, which suggested the Guanches might be related in some way to the Ice Age Cro-Magnons (later anthropological research dispelled this idea however).

Verneau traveled among the Canary Islands during 1876 and 1877, studying skeletons of the aboriginal population and examining prehistoric tombs. He returned to Paris in the autumn of 1877 and presented a report on his investigations to the Ministry of Public Education. This experience initiated Verneau’s lifelong passion for the Canary Islands, which he would visit six times over the course of his life. When the Museo Canario was established in 1879, through the initiative of the Canarian physician and anthropologist Gregorio Chil y Naranjo, Verneau was named an honorary member of the museum along with Quatrefages and Sabin Berthelot (the French consul in the Canary Islands). The museum, located in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, collected anthropological and archaeological material relating to the aboriginal population of the Canary Islands. Verneau spent portions of his career collecting objects for the museum and later he reorganized much of the anthropological collection of the museum.

In addition to working as a prèparateur at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, Verneau was also appointed a professor at the Association polytechnique in 1879 where he taught a course in anthropology for the general public. Throughout his career, Verneau displayed an interest in bringing the discoveries of anthropology to a wider public through lectures and books. In 1884 he returned to the Canary Islands and spent the next few years, until 1887, exploring all the islands of the archipelago. During this trip, he examined prehistoric tombs and caves, such as the Cueva Pintada (Painted Cave), studied the contemporary culture of the Guanches, and assembled a skeletal and ethnographic collection of the islands’ peoples. After returning to Paris Verneau wrote a book, Cinq années de séjour aux Îles Canaries [Five Years Living in the Canary Islands] published in 1891, that recounted his travels and investigations of the archipelago.

Verneau was promoted to assistant at the Museum of Natural History in 1892, working under Ernest-Théodore Hamy who had succeeded Quatrefages to the chair of anthropology. That same year, he also taught a course on anthropology at the Enseignement populaire supérieur in Paris. In addition to his teaching and research, Verneau published a popular book on human prehistory titled L’enfance de l’humanité [The Childhood of Humanity] (1890). His career was now advancing quickly. He served as the editor, jointly with paleontologist Marcellin Boule, of the journal L’Anthropologie from 1894 to 1930. The journal was founded by Verneau, Boule, and Hamy when the Revue d’ethnographie, which ceased publication in 1889, merged with Matériaux pour l’histoire primitive et naturelle de l’homme and Révue d’anthropologie to form the new journal L’Anthropologie. Verneau also became a member of the Société des américanistes (Society of Americanists), founded by Hamy in 1895 with a dedication to the ethnological and anthropological study of the native peoples and cultures of the New World. Among his many anthropological researches, Verneau studied the early inhabitants of Patagonia in South America, which resulted in an important monograph titled Les anciens Patagons [The Ancient Patagonians] published in 1903. In addition to his growing number of responsibilities, in 1900 he served as the secretary general of the Congrès international d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques [International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology] meeting in Paris.

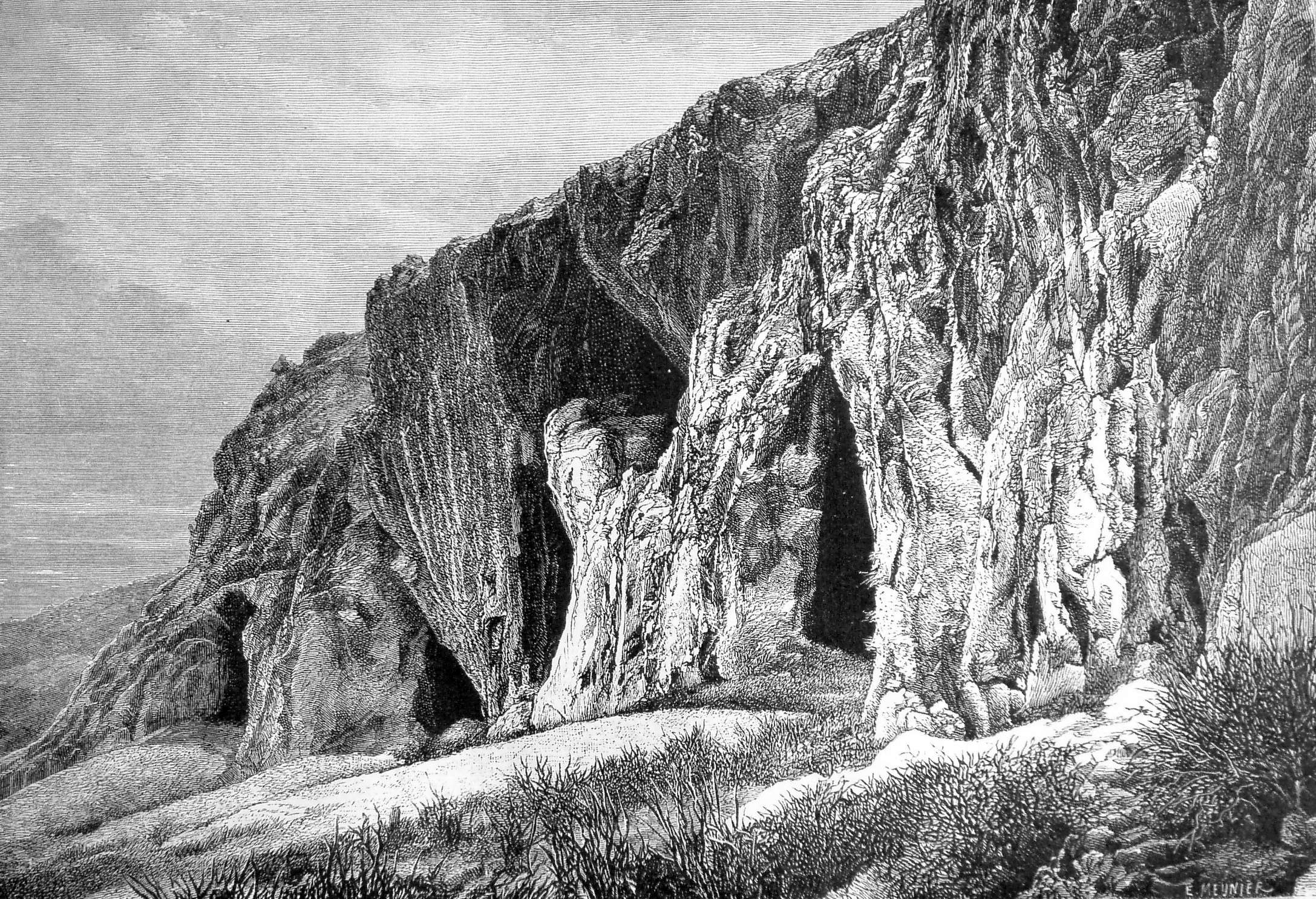

Verneau was increasingly becoming involved in the study of prehistoric humans. He had already published several papers on prehistoric skeletons, but when new human skeletons were unearthed at Baoussé-Roussé (Balzi Rossi), on the coast of Italy just across the border from the French village of Menton, he was invited to examine them. Excavations conducted there by French archaeologist Émile Rivière between 1870 and 1875 had uncovered several Cro-Magnon skeletons along with Paleolithic artifacts. The caves strewn along the cliffs at Baoussé-Roussé continued to attract the attention of excavators over the following years. Louis Julien, an antiquities dealer, excavated a human skeleton in the Barma Grande cave in February 1884, and during subsequent excavations, he unearthed several statuettes made of soapstone. Following Julien’s excavations François Abbo purchased the site and began quarrying operations. On 7 February 1892, Abbo unearthed a human skeleton during quarrying work in the Barma Grande cave and several days later two more skeletons were unearthed along with flint artifacts, ivory pendants, and shell ornaments. The Ministry of Public Education in France requested the Museum of Natural History in Paris to investigate these discoveries, and Hamy asked Verneau to undertake an examination of these finds. No precise records were made of the initial discoveries, and Verneau arrived at the site two weeks after they were made. Joseph Abbo, the owner’s son, continued to conduct excavations, and on 12 January 1894, he unearthed a fourth skeleton near the bottom of the cave, and soon thereafter a fifth charred skeleton was found. Verneau studied these five skeletons as well as the skull found by Julien in 1884, which had been preserved in the Menton museum. Verneau published a series of papers on these skeletons (Verneau 1892a; 1992b; 1894; 1899) and eventually a monograph titled L’homme de la Barma-Grande (Baoussé-Roussé) [The Humans of Barma-Grande] (1899) that described the human fossils from the Barma Grande cave and compared then with the human skeletons previously found there by Rivière and with Cro-Magnon skeletons found elsewhere in France.

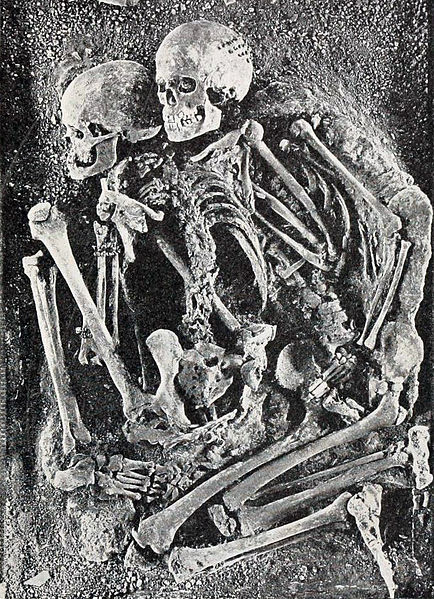

These new discoveries at Baoussé-Roussé attracted the attention of Prince Albert I of Monaco, who had an intense interest in human prehistory. After conducting some excavations of his own there in 1895, he financed the excavation of the eight most important caves at Baoussé-Roussé, which came to be called the caves of Grimaldi since they were located in the commune of Grimaldi. Léonce de Villeneuve, an ordained priest and Canon of Monaco who was also an archaeologist and paleontologist, conducted the excavations with the assistance of Frederico Lorenzi. In a cave called the Grotte des Enfants, they found numerous artifacts and reindeer bones in the upper layers, while the lower layers contained a warmer climate fauna that included Merck’s rhinoceros, hippopotamus, and straight-tusked elephants. The lowest layer held Mousterian tools. Unlike earlier excavators, Villeneuve carefully recorded the stratigraphy in the cave, which allowed an accurate dating of the fossils and artifacts found there. On 10 April 1901, Villeneuve unearthed a female skeleton associated with pierced shells that probably formed some kind of ornament [this skeleton is now considered to be Mesolithic]. Below this skeleton, he found a male skeleton buried with its arms crossed over its chest and pierced shells and deer teeth ornaments were found on the body. Then on 3 June 1901, Villeneuve unearthed the skeletons of an elderly woman buried along with an adolescent boy. These two skeletons lay immediately below the male skeleton found earlier, and they too were found with flint artifacts and shell ornaments.

Marcellin Boule, professor of paleontology at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, was invited to study the animal fossils that Villeneuve and Lorenzi discovered. Émile Cartailhac, professor of prehistoric archaeology at the University of Toulouse, undertook the study of the artifacts. Verneau conducted the study of the human remains, and he soon became convinced that two different groups were present. He noted that the two skeletons found in the deepest later of the cave, the old woman and the adolescent boy, differed anatomically from the skeletons found above them in the cave. When he compared the new skeletons from the Grotte des Enfants with skeletons found previously in the caves of Baoussé-Roussé (those found by Émile Rivière in the 1870s and by Louis Julien and Joseph Abbo at Barma Grande) Verneau observed that all these skeletons, with the exception of the old woman and the adolescent, resembled the Cro-Magnon people whose fossils were known from various Paleolithic sites in Europe. When he examined the skeletons of the old woman and the adolescent boy, however, Verneau concluded that they possessed “Negroid traits” and displayed features that differed in noticeable ways from Cro-Magnon skeletons. He argued that these two skeletons represented a hitherto unknown Paleolithic race of humans that he called the “race de Grimaldi” (Grimaldi race).

The impressive results of these excavations were published at the expense of Prince Albert I in a detailed two volume work titled Les Grottes de Grimaldi (Baoussé-Roussé) (1906-1919), with Villeneuve, Boule, Cartailhac, and Verneau contributing sections pertaining to their areas of expertise. They describe the excavations, the animal fossils, and the human remains and archaeological artifacts. On the basis of the stratigraphy and the animal fossils Boule believed the human skeletons dated from what he called the “early part of the Reindeer Age,” which would place them in the Middle Pleistocene (they are now attributed to the lower Aurignacian). Verneau’s description of the skeletons from the Grotte des Enfants along with the skeletons he had studied from Barma Grande and those excavated by Émile Rivière resulted in one of the most important revisions of paleoanthropologists’ understanding of Cro-Magnons since the original work of Broca, Quatrefages, and Hamy in the 1860s and 1870s. Verneau also argued, on the basis of all this new evidence, that Paleolithic humans buried their dead, contrary to the long-held view of Gabriel de Mortillet and others that it was impossible that such primitive and early people could have engaged in such a practice. The skeletons and artifacts recovered during these excavations were placed in the collections of the Musée d’anthropologie préhistorique [Museum of Prehistoric Anthropology] in Monaco, which was founded in 1902 by Prince Albert I who appointed Léonce de Villeneuve the Museum’s first director.

Verneau’s identification of a Grimaldi race among the Paleolithic skeletons at Baoussé-Roussé influenced the thinking of paleoanthropologists throughout the early twentieth century. He came to believe that the earliest Homo sapiens possessed Negroid traits and that the first humans to inhabit Europe were Negroid. He supported these claims on the basis of examinations of prehistoric skeletons from various parts of Europe. In addition to his study of Paleolithic humans, Verneau also studied Neolithic skeletons. Among them were the human skeletons that Léonce de Villeneuve excavated from the Neolithic tombs in the Grotte des Bas-Moulins in Monaco (Verneau and Villeneuve 1901). He also continued to conduct anthropological studies of living populations. He wrote the volume on ethnography and anthropology for the Mission in Ethiopia (1901-1903), led by Jean Duchesne-Fournet under the auspices of the Ministry of Public Instruction, which studied the geography, geology, zoology, and anthropology of Ethiopia (Jean Duchesne-Fournet et al. 1908-1909).

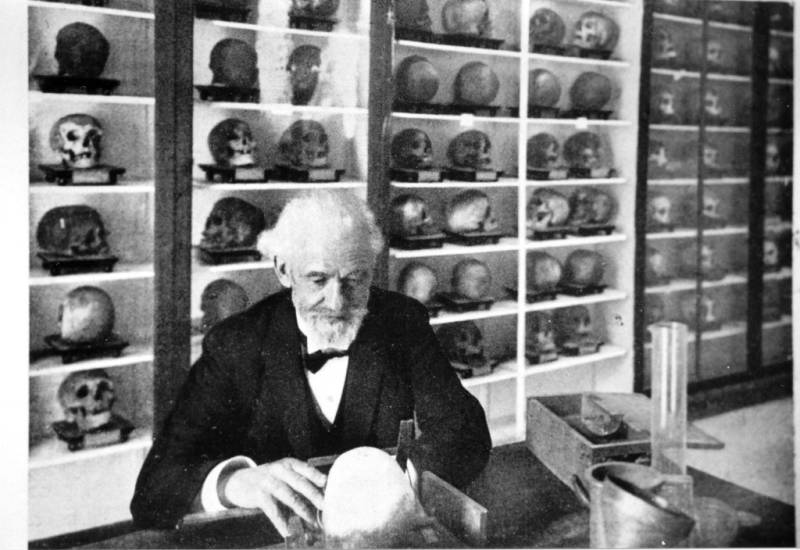

Verneau’s professional life changed notably following the work on the Paleolithic human fossils from Baoussé-Roussé. He taught a course on human paleontology at the École d’Anthropologie in 1905 where he discussed the important human fossils discovered in Europe as well as his views on prehistoric human races. After working for four years at the Musée d’ethnographie du Trocadéro [Museum of Ethnography] housed in the Trocadéro Palace in Paris, Verneau was appointed the conservateur [curator] of the museum in 1907. He succeeded Ernest-Théodore Hamy who resigned as the museum’s director in 1906 in protest over the dismal state of the museum’s budget and the lack of support for the institution. Then in 1909, after many years working as an assistant, Verneau succeeded Hamy to the chair of anthropology at the Museum of Natural History. One of his main objectives was to integrate the ethnographical and the anthropological approaches to the study of humans, which were often treated separately by French ethnographers who were interested in the cultures of different peoples and French anthropologists who often were focused on craniometric and anthropometric examinations of human bodies in order to identify their racial classification.

French anthropological institutions were also undergoing change at this time as the field became more developed and there were a larger number of researchers engaged in anthropology related investigations. Verneau resigned from the Société d’anthropologie de Paris in 1910 as a result of a dispute with Adrien de Mortillet over the work of a commission investigating the mixing of races. He was one of the founding members, along with Marcellin Boule and other leading French scientists, of the Institut Français d’Anthropologie [French Institute of Anthropology] when it was established in 1911. The Institute was founded in some respects in opposition to the Société d’anthropologie de Paris, which focused on physical anthropology and the identification of racial characteristics. The Institute, instead, wanted to unite ethnographic studies of cultures with anthropological studies of race. Verneau succeeded Boule as president of the Institute in 1922. One of the most influential new institutions to be created was the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine [Institute of Human Paleontology]. Prince Albert I of Monaco founded the Institute in 1910 as a research institution devoted to the study of human prehistory. Marcellin Boule was appointed professor of paleontology as well as the Institute’s director, Henri Breuil was the professor of prehistoric ethnography, Émile Cartailhac the professor of archaeology, Hugo Obermaier the professor of geology, and René Verneau the professor of prehistoric anthropology. The building housing the Institute opened in Paris in 1920 and its members conducted excavations, assembled collections of prehistoric objects, and published their research under the auspices of the Institute.

The First World War deeply affected European science. During the war, Verneau held the position of chief medical officer at Juvisy where there was a military school. The war damaged relationships between French and German scientists, and this interrupted the international cooperation that characterized European science before the war. Besides affecting the relationships between individual scientists, it also affected scientific institutions, with some excluding members from the defeated nations or breaking their contact with fellow institutions in those countries. As a consequence of the war, a group of prominent French anthropologists circulated a notice on 20 November 1918 calling for the creation of an Institut International d’Anthropologie [International Institute of Anthropology. The Institute was established in 1921 with the purpose of bringing archaeologists and anthropologists together after the war, but scientists from Germany and Austria were excluded from the Institute’s activities. But some influential prehistorians and anthropologists, including Verneau, Boule, Hugo Obermaier, and Pedro Bosch-Gimpera, argued that the Institute should open its membership to scientists from all countries.

Verneau was a founding member of the Académie des Sciences Coloniales [Academy of Colonial Sciences], which was created in 1922. He was also a member of the Commission des Monuments Préhistoriques [Prehistoric Monuments Commission]. In 1924 he was awarded the Huxley Medal by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland and in his paper for the Huxley Lecture Verneau took the unusual position of supporting the view that the Neanderthals were the direct ancestors of Homo sapiens (Verneau 1924). Verneau’s best known book was Les origines de l’humanité [The Origins of Humanity] (1926), which was written for a general audience and discussed Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon fossils, the Grimaldi skeletons, the Chancelade skeleton, and the Paleolithic archaeological record.

Verneau received a number of awards and honors throughout his career. He was awarded the Medal of the Société de Géographie Commerciale de Paris (Paris Commercial Geography Society) in 1924. He was Officier de la Légion d’honneur (Officer of the Legion of Honor), and in 1931 he was elevated to the rank of Commandeur de la Légion d’honneur (Commander of the Legion of Honor). He was also an Officier de l’Instruction publique [Officer of Public Education]. He received a number of foreign honors as well. The Spanish government made Verneau a Commander of the Order of Isabelle-la-Catholique as well as a Commander of the Order of Alphonso XII. The government of Monaco named him an Officer of the Order of Saint-Charles de Monaco, and the government of French Indo-China named Verneau Commander of the Imperial Order of the Dragon of Annam in recognition of his scientific work in Indo-China.

After successively holding positions as prèparateur, assistant, and professor of anthropology at the Museum of Natural History, Verneau retired from his position at the Museum in 1927. The following year he retired from his position as curator of the Museum of Ethnography. He remained professor of prehistoric anthropology at the Institute of Human Paleontology until 1937. Verneau died on 7 January 1938 in Paris.

Selected Bibliography

René Verneau and Alfred Edmund Brehm, Les races humaines. Paris J.-B. Baillière et Fils, 1890.

Le bassin dans les sexes et dans les races. Paris: Baillière, 1875.

“Crâne moderne de type de Cro-Magnon.” Bulletins de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris ser. 2, 11 (1876): 408-417.

“Crânes de l’allée couverte de Montigny-l’Engrain. La race de Furfooz à l’époque des dolmens.” Bulletins de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris ser. 3, 10 (1887): 713-725.

L’enfance de l’humanité. Paris: Hachette et Cie, 1890.

Cinq années de séjour aux iles Canaries. Paris: A. Hennuyer, 1891.

“Note sur une nouvelle découverte de troglodytes dans une grotte des Baoussé-Roussé, commune de Vintimille (Italie).” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 36 (1892): 95-101.

“Nouvelle découverte de squelettes préhistoriques aux Baoussé-Roussé, près Menton.” L’Anthropologie 3 (1892): 513-540.

“Découverte d’un nouveau squelette humain dans une grotte des Baoussé-Roussé.” L’Anthropologie 5 (1894): 123-124.

“Les nouvelles trouvailles de M. Abbo dans la Barma-Grande, près de Menton.” L’Anthropologie 10 (1899): 439-452.

L’homme de la Barma-Grande (Baoussé-Roussé): étude des collections réunies dans le museum praehistoricum fondé par Thomas Hanbury près de Menton. Baoussé-Roussé: Fr. Abbo, 1899.

The Men of the Barma-grande (Baoussé-Roussé): An Account of the Objects Collected in the Museum Præhistoricum, Founded by Commendatore Th. Hanbury near Mentone. Transl. by O. C. and B. C. Baoussé-Roussé, near Mentone: F. Abbo, 1900.

Les Boers et les races de l’Afrique Australe. Paris: Armand Colin & Cie, 1899.

René Verneau and L. de Villeneuve, “La grotte des Bas-Moulins (principauté de Monaco).” L’Anthropologie 12 (1901): 1-27.

Les anciens Patagons: contribution à l’étude des races précolombiennes de l’Amérique du Sud. Monaco: Imprimerie de Monaco, 1903.

“Crâne de Baoussé-Roussé.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris ser. 5, 5 (1904): 559-570.

Léonce de Villeneuve, Marcellin Boule, René Verneau, and Émile Cartailhac, Les Grottes de Grimaldi (Baoussé-Roussé). 2 vols. Monaco: Imprimerie de Monaco, 1906-1919.

René Verneau and Paul Rivet, Ethnographie ancienne de l’Equateur. Paris, Gauthier-Villars, 1912.

René Verneau and Georges de Gironcourt, Résultats anthropologiques de la mission de M. de Gironcourt en Afrique occidentale. Paris: Masson, 1918.

“La race de Neanderthal et la race de Grimaldi: leur role dans l’humanité.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 54 (1924): 211-230.

Les origines de l’humanité. Paris: F. Rieder et cie, 1926.

L’homme: races et coutumes. Paris: Larousse, 1931.

Other Sources Cited

Jean Duchesne-Fournet et al., Mission en Éthiopie (1901-1903). 2 vols. Paris: Masson et cie, 1908-1909.

Secondary Sources

“Verneau (René).” In Qui êtes-vous?: Annuaire des contemporains; notices biographiques, p. 750. Paris: Delgrave, 1924.

Henri Vallois, “René Verneau,” L’Anthropologie 48 (1938): 381-389.

R. L. “Le Dr. René Verneau (1852-1938).” Revue archéologique 12 (1938): 85.

George Montandon, “René Verneau.” Revue anthropologique 48 (1938): 86-88.

Marcel Mauss, “René Verneau: 25 April, 1852-7 January, 1938.” Man 39 (1939): 12-13.

Gérard Cordier, “Un illustre Bourgueillois méconnu: le docteur René Verneau (1852-1938),” Bulletin de la Société des Amis du Vieux Chinon 8 (1984): 1089-1092.

Frank Spencer, “Verneau, René (Pierre) (1852-1938).” In Frank Spencer (ed.) History of Physical Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. 2 vols. Vol. 2, pp. 1091-2. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997.