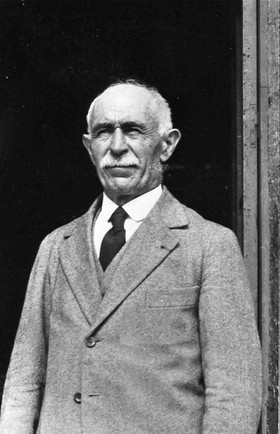

Denis Peyrony (1869-1954)

Matthew Goodrum

Denis Peyrony was born 21 April 1869 in Cussac, in the Dordogne region of France. His parents were farmers, but after studying at the École supérieure in Belvès and then at the École normale of the Department of Dordogne, Peyrony became a schoolteacher in the village of Eyzies-de-Tayac in 1891. In 1894, prompted by an interest in prehistory, he took a course taught by the French archaeologist Émile Cartailhac. Peyrony also became friends at this time with Louis Capitan, who was a professor at the École d’Anthropologie [School of Anthropology] in Paris, and the two men began a long collaboration surveying and excavating prehistoric sites in France. In September 1901, Capitan, Peyrony, and prehistorian Henri Breuil discovered the decorated caves of Combarelles and of Font-de-Gaume after a local farmer brought Peyrony a small female statue found in the road near the site. The caves contained depictions of animals on its walls similar to those found by Émile Rivière at the Grotte de la Mouthe in 1895. These discoveries were made at a time when cave paintings and engravings depicting Pleistocene animals were still viewed with great skepticism by European archaeologists, and these new finds contributed to changing attitudes about Paleolithic cave art. Their work resulted in two important monographs, published under the auspices of Albert I of Monaco: La caverne de Font-de-Gaume aux Eyzies (Dordogne) published in 1910 and Les Combarelles aux Eyzies (Dordogne) published in 1924. Peyrony soon discovered other engravings on the walls of the Grotte de Bernifal in 1902 and on the walls of the Grotte de La Calévie and at the Grotte de Teyjat in 1903.

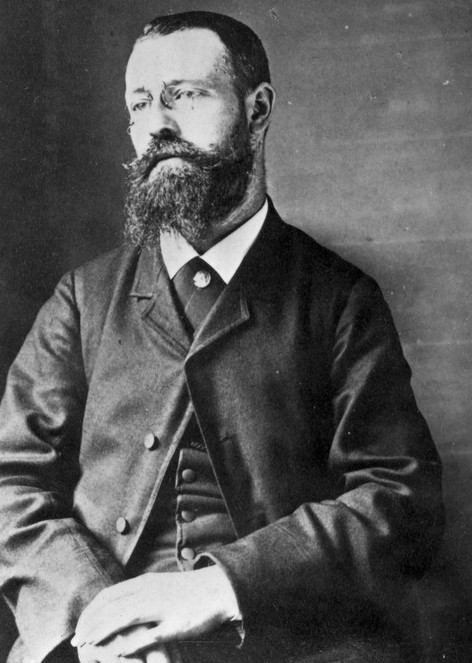

Following these discoveries, Peyrony began excavations at a number of Paleolithic rock shelters and caves located in the Dordogne region, usually in collaboration with Capitan or Breuil. He collaborated in excavations with Henri Breuil in 1908 that examined the stratigraphy of the Pagès rock shelter. They were not the only excavators exploring the Paleolithic sites of this archaeologically rich region. The Swiss amateur archaeologist Otto Hauser began excavations at La Micoque in 1906 and at Le Moustier in 1907 that produced numerous artifacts. In March 1908, Hauser’s excavations at Le Moustier unearthed a human skeleton that was later identified as being a Neanderthal. Hauser then undertook excavations at Combe-Capelle in 1907 that resulted in the discovery in August 1909 of a human skeleton along with Aurignacian artifacts. To the great chagrin of French scientists, Hauser sold the precious skeletons found at Le Moustier and Combe-Capelle to the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin after asking an exorbitant amount of money that no institutions in France were willing to pay. In fact, Hauser had been selling Paleolithic artifacts retrieved from his excavations in the Dordogne for years in order to fund his archaeological researches. Matters got worse when it was learned that one of the so-called Laussel Venus sculptures discovered by Gaston Lalanne in the Grotte de Lausel in 1911 had also been sold to the Museum für Völkerkunde.1 These events angered French scientists and politicians to such an extent that the French government finally passed a law in 1913 protecting antiquities and banning their export in order to combat what they saw as foreign plundering of important artifacts. Hauser was forced to leave France in 1914 with the beginning of World War I.

Prompted by concern over Hauser’s excavations and the sale of artifacts abroad, Capitan and Peyrony convinced the French government to purchase the Paleolithic sites of Le Moustier, Laugerie-Haute, and La Micoque previously owned by Otto Hauser. In 1913 they also induced the government to purchase the Château des Eyzies-de-Tayac in order to transform it into a museum. Construction was delayed by World War I, but in 1918 the Musée National de Préhistoire [National Museum of Prehistory] opened, although the official opening of the museum did not occur until 1923. Peyrony was appointed its first director, and the museum housed his personal collection of artifacts. By this time, Peyrony already held a number of professional positions. He was a non-resident member of the Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques, an organization created in Paris in 1834 and funded by the state in order to encourage historical and scientific research. In addition, in 1911 he was appointed chargé de mission (project manager) of the Prehistoric section of the Commission des Monuments Historiques [Commission of Historic Monuments], which was part of the Ministère de 1’Instruction et des Beaux-Arts. This position offered a rare case where an excavator received public funds for archaeological work from the Ministère de l’Instruction Publique. Peyrony used each of these positions to protect archaeological sites and limit the damaging activities of antiquities hunters and amateur excavators.

Peyrony initiated new excavations at Le Moustier in 1910 where he uncovered an important sequence of Paleolithic strata and discovered an infant Neanderthal skeleton in 1914. He and Capitan also began new excavations at the rock shelter of La Madeleine in 1911-12, where they recorded stratigraphic changes in stone and bone artifacts and collected specimens of portable art. In fact their collection of Paleolithic portable art recovered from various sites had grown so large that they donated a substantial number of objects to the Musée des Antiquités Nationales [Museum of National Antiquities] in 1912. Meanwhile, events elsewhere soon demanded their attention. Excavations conducted by the Bordeaux physician Gaston Lalanne in the rock shelter of Cap Blanc, near Les Eyzies, had discovered carved images of horses, bison and reindeer in 1909. He had also recovered stone and bone tools at the site. Construction in 1911 designed to protect the newly discovered rock carvings unexpectedly unearthed a Magdalenian human skeleton at the site. Capitan and Peyrony were immediately invited to excavate the skeleton in order it to insure the excavation would conform to the highest scientific standards, which was a measure of the respect these two researchers commanded as a result of their previous work. From 1912 to 1913, Peyrony also excavated the Roque Saint-Christophe site, and he conducted excavations at the Poisson rock shelter from 1917 to 1918.

Of particular importance were the excavations Peyrony and Capitan conducted at La Ferrassie, located in the Vézère valley, between 1902 and 1922, although they had originally explored the site in 1896. At La Ferrassie they found Mousterian and Aurignacian artifacts and a total of six Neanderthal burials. The first of these, La Ferrassie 1, was a male skeleton with a nearly complete skull that was discovered on 17 September 1909. La Ferrassie 2 was an incomplete cranium and skeleton of a female Neanderthal that was found in 1910. The skeletons of two infants were unearthed in 1912, followed by another infant in 1920. La Ferrassie 6 was a nearly complete skeleton of a child discovered in 1921. Due to the rarity and significance of these discoveries, Capitan and Peyrony invited Marcellin Boule (the professor of paleontology at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle who examined the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neanderthal skeleton discovered in 1908), prehistoric archaeologist Émile Cartailhac, and prehistorian Henri Breuil to participate in the examination of these specimens. All of these skeletons were given to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle [National Museum of Natural History] in Paris.

Throughout the 1920s, Peyrony excavated and recorded the stratigraphy of Le Moustier, La Madeleine, and Laugerie-Haute. In 1926 he discovered the skeleton of an infant covered in shells at La Madeleine, which he later donated to the Musée National de Préhistoire. Peyrony also initiated new excavations at La Micoque from 1929 to 1932. There he identified fifteen stratigraphic layers and identified an archaeological industry he called the Tayacian consisting of large stone flake tools, which lay immediately below an archaeological layer that Otto Hauser had named the Micoquian industry. Peyrony’s excavations and careful attention to stratigraphy across such a large number of Paleolithic sites allowed him to work out the chronology of the Middle and Upper Paleolithic. Using artifact typology and stratigraphy, he identified a regional succession of industries or cultures, some of which he believed coexisted in the Paleolithic. This contradicted the widely adopted scheme proposed by Gabriel Mortillet that arranged Paleolithic archaeological industries in a single linear sequence. Peyrony identified what he believed were a succession of distinct archaeological industries within Mortillet’s Solutrean and Magdelenian. His work also showed that the Aurignacian was very complex, and in the early 1930s, he created the term “Périgordien” to refer to an Upper Paleolithic industry that developed in parallel and coexisted with the Aurignacian, although archaeologists later abandoned this idea. Peyrony argued that these cultural changes, represented by changes in artifacts, could be explained as the result of changes in climate and fauna as well as the arrival of distinct races of prehistoric humans. Peyrony’s investigations of Paleolithic artifacts and chronology influenced Henri Breuil’s ideas about Paleolithic archaeology and especially his division of the Magdalenian into six phases.

In addition to his scientific labors, Peyrony began to organize visits for the public to the prehistoric sites of the Eyzies-de-Tayac region, the first of which occurred in 1920. Peyrony’s research earned him the respect of his colleagues, which led to his becoming a member of the Société historique et archéologique du Périgord and a corresponding member of the Académie nationale des Sciences, Belles-Lettres et Arts de Bordeaux. He also served as a delegate and as a correspondent of the Ministère de l’Instruction Publique. In 1929 Peyrony was appointed Inspecteur des Monuments Préhistoriques [inspector of prehistoric monuments] with responsibilities to monitor, manage, and protect historic sites. This was the same year that his friend and colleague Louis Capitan died, thus ending their long collaboration, although Peyrony continued to excavate and publish into the 1940s. Peyrony died 25 November 1954 in Sarlat, France.

Selected Bibliography

Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony. “Fouilles à la Ferrassie (Dordogne).” Congrès préhistorique de France compte rendu [1905] (1906): 143-144.

Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony. “Deux squelettes humains au milieu de foyers de l’époque moustérienne.” Revue d’Anthropologie 19 (1909): 404-409.

Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony. “Un nouveau squelette humain fossile.” Revue d’Anthropologie 21 (1911): 148-150.

Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony. “Station préhistorique de La Ferrassie, commune de Savignac-du-Bugue(Dordogne).” Revue d’Anthropologie 22 (1912): 76-99.

Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony. “Trois nouveaux squelettes humains fossiles.” Revue d’Anthropologie 22 (1912): 439-442.

Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony. “Nouvelles fouilles à La Ferrassie (Dordogne).”

C. R. Association française pourl’avancement des sciences (1921): 540-542.

Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony. “Découverte d’un sixième squelette moustérien à la Ferrassie (Dordogne).” Revue d’Anthropologie 31 (1921): 382-388.

Denis Peyrony. “Découverte d’un squelette humain à La Madeleine,” Actes de la troisième session de l’Institut international d’ anthropologie, Amsterdam, 1927, 3, p. 318-320.

Louis Capitan, Henri Breuil, and Denis Peyrony. La caverne de Font-de-Gaume aux Eyzies (Dordogne). Monaco: A. Chêne, 1910.

Denis Peyrony. Élements de préhistoire. Ussel: G. Eyboulet & Fils, 1914.

Louis Capitan, Henri Breuil, and Denis Peyrony. Les Combarelles aux Eyzies (Dordogne). Paris: Masson, 1924.

Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony. La Madeleine: son gisement, son industrie, ses oeuvres d’art. Paris: E. Nourry, 1928.

Denis Peyrony. Les gisements préhistoriques de Bourdeilles (Dordogne). Paris: Masson, 1932.

Denis Peyrony. “La Ferrassie: Moustérien-Périgordien-Aurignacien,” Préhistoire 3 (1934): 1-92.

Secondary Sources

Henri Breuil, “Nécrologie de monsieur Denis Peyrony,” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 51 (1954): 530-533.

Randall White and Alain Roussot, “Résumé de ma vie: une note autobiographique de Denis Peyrony.” Bulletin de la Société Historique et Archéologique du Périgord. 125 (2003): 453-472.

Notes

1 Raymond Peyrille, the man hired by Lalanne to direct the excavations, was apparently induced to sell the precious Paleolithic figurine by Max Verworn, professor of physiology at the University of Bonn.