Édouard Lartet (1801-1871)

Matthew Goodrum

Édouard-Armand-Isidore-Hippolyte Lartet was born on 15 April 1801 in the parish of Saint-Guiraud, near Castelnau-Barbarens, Gers, in the southwest region of France. His father, Jean-Hospice Lartet, descended from a family of wealthy landowners and lived at the family estate of En Poucouron, where his ancestors had resided for more than three centuries. Lartet attended the lycée in the nearby town of Auch where he excelled as a student. In 1808, the young Lartet received a medal from Napoleon I in recognition of his academic achievements during the emperor’s visit to Auch. Lartet studied law at the University of Toulouse and obtained a diploma and license in law in 1820. He then went to Paris in 1821 to complete a practical internship (stage pratique). While in Paris, Lartet visited the collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History) and read books on natural history, many of which emphasized the ideas of the famous French geologist and zoologist Georges Cuvier.

Lartet returned to Gers in 1830 where he practiced law until 1834, but with his father’s death he took over the administration of the family property and lived at the family home, the chateau of Ornezan, in Castelnau-Barbarens. His income now allowed Lartet to devote his time to scientific interests and he developed relationships with local scientists, notably abbé François Caneto who taught science at the seminary in Auch. Lartet seems to have acquired an interest in paleontology when he was given a mastodon tooth by a local farmer from Sansan in payment for legal advice. Farmers in the area frequently turned up fossils while plowing, so Lartet went to Sansan to examine the site for himself. Animal fossils dating from the Miocene were abundant and Lartet immediately began excavations at Sansan and other nearby sites. This resulted in the discovery of large numbers of Miocene vertebrates such as mastodon, dinotherium, rhinoceros, and paleotherium—many of which were new to science. Having no formal training in geology and paleontology, Lartet sent a letter describing his discoveries to Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, professor of zoology at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, who read Lartet’s letter before the members of the Société Géologique de France (Geological Society of France) in 1834 (Lartet 1834).

Lartet’s discovery at Sansan of fossilized bones belonging to an ape elevated the importance of his excavations. Lartet unearthed a partial mandible in December 1836 and immediately prepared a report on the fossil that was read before the Académie des Sciences (Academy of Sciences) in Paris on 16 January 1837 (Lartet 1837a). This announcement attracted attention and in the following months Lartet recovered several more ape bones, including another partial mandible and two femurs. Lartet composed a second paper describing these discoveries and this was read at the 17 April meeting of the Académie des Sciences (Lartet 1837b). These fossils generated great interest but also some controversy among French naturalists because they were the first ape fossils discovered in Europe. Some naturalists were doubtful that ape fossils could have been recovered from Miocene deposits because of the lasting legacy of the renowned comparative anatomist and paleontologist Georges Cuvier. Cuvier, who had been an influential professor at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle during the early nineteenth century, had argued, in his Discours sur les révolutions du globe (Discourse on the Revolutions of the Globe) (1826), that apes had appeared geologically recently and therefore fossil apes did not exist. Many naturalists continued to support this opinion leading to a need for Lartet’s claims to have found ape fossils in Miocene deposits to be confirmed.

At the 23 January 1838 meeting of the Académie des Sciences, comparative anatomist Henri de Blainville, geologist Pierre-Louis-Antoine Cordier, and François Arago called for a committee to be formed to obtain funds from the Academy to support Lartet’s work at Sansan. Lartet also sent the ape fossils he had collected to the Academy for its members to inspect. Following the presentation in April of Lartet’s paper, the Academy formed a commission led by Henri de Blainville, who was a professor at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, anatomist André-Marie-Constant Duméril, and anatomist Marie-Jean-Pierre Flourens to investigate Lartet’s claims. The commission produced two reports describing the ape fossils and confirming his claims for their geologic age, and they encouraged Lartet to continue his excavations (Duméril, Flourens, de Blainville 1837; Duméril, Flourens, de Blainville 1838). Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, who had read Lartet’s first scientific paper before the Société Géologique de France in 1834, was very excited by Lartet’s ape fossils and expressed the opinion that he thought the fossils opened a new field of primate paleontology and that they bore important implications for understanding the human past (Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1837). The members of the Academy commission also acknowledged the significance of these ape fossils and their possible significance for the ongoing debate over how long humans had existed and whether humans had possibly coexisted with extinct animals such as mammoths and the wooly rhinoceros (Duméril, Flourens, de Blainville 1838). Henri de Blainville conducted a careful examination of the ape fossils from Sansan and determined that they belonged to an extinct species that he named Pithecus antiquus in 1839, but the paleontologist and zoologist Paul Gervais renamed the species Pliopithecus antiquus in 1849.

Because of the many fossils, and especially of the Pliopithecus fossils, which he had collected at Sansan Lartet began interacting regularly with scientists at the Académie des Sciences and the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, particularly Henri de Blainville and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Lartet’s new allies encouraged the Académie des Sciences to support Lartet’s excavations and they also approached François Guizot, the Minister of Public Instruction, for financial support for Lartet’s work with the objective of acquiring specimens for the paleontological collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. Narcisse-Achille de Salvandy, who served as Minister of Public Instruction from April 1837 to March 1839, continued to provide funds for Lartet’s work and for the state acquisition of the fossils he was extracting. In addition, Constant Prévost, professor of geology at the University of Paris, traveled to Gers to see Lartet and to inspect the immense collection of vertebrate fossils that Lartet had accumulated, which included reconstructed mammal and reptile specimens. Prévost was convinced by what he saw at Sansan that the site needed to be purchased by the French government in order to guarantee continued excavation of the site and he agreed that Lartet’s specimens should be acquired by the Museum. This was a pressing matter since several industrial companies were interested in exploiting the site and several foreign museums were interested in purchasing Lartet’s fossils for their museums. Lartet, however, wanted his specimens to remain in France and a commission was established in 1847 to produce a report regarding these issues. Through an agreement arranged between Lartet, Prévost, and the Ministry of Public Instruction, the French government purchased the site of Sansan in 1849.

While Lartet was conducting excavations as Sansan he also began work at the nearby site of Simorre, which also contained Miocene mammal fossils, but by 1837 he realized that the species he was recovering from Simorre were different from those found at Sansan. Paleontology now consumed most of Lartet’s efforts, but there were developments in his personal life as well. On 11 February 1840, Lartet married Joséphine-Léonide Barrère and moved into the chateau La Bernisse, in the nearby town of Seissan, the following year. As the excavations at Sansan and Simorre continued, his collection of remarkable Miocene animals and his ideas about the history of life grew. He employed new methods in the course of his work, such as transporting sediment from the field to his garden where it was washed and sieved to extract even the smallest fragments of bone. He sent a major paper on the results of his work to the Académie des Sciences in 1845 (Lartet 1845) and published a short work cataloguing the species he had collected (Lartet 1851). In 1852, concerned about his son Louis’ education, the Lartet family left Gers to settle in Toulouse, then moved to Paris two years later. His circle of scientific friends expanded after these two moves and included naturalists Jean-Baptiste Noulet and abbé Dominique Dupuy, and paleontologist Saint Ange de Boissy. In Paris, Lartet became friends with many leading geologists and paleontologists and participated in the scientific life of the city.

Lartet collaborated with geologist Albert Gaudry in studying and describing the Miocene fossils that Gaudry had collected from Pikermi, in Greece, and comparing them with the specimens that Lartet had collected from Sansan (Gaudry and Lartet 1856). In 1857, Lartet named a new genus of toothed bird, Pelagornis miocaenus, based on a humerus bone that abbé Dominique Dupuy found in Armagnac, in Gers. He continued to unearth remarkable fossils, sending crates of bones to the Museum in Paris, and working to reconstruct such creatures as the fossil rhinoceros, Brachypothérioum, a proboscidean called Archeobelodon, and other Miocene animals. In 1856, Lartet published a description of yet another new Miocene fossil ape. A fossil collector, Alfred Fontan, had found a partial mandible and a humerus bone at Saint-Gaudans that were sent to Lartet. The new ape was named Dryopithecus fontani (Lartet 1856) and many scientists, such as Albert Gaudry, considered this specimen to be even more important than Pliopithecus antiquus because it was more anatomically similar to humans than Pliopithecus.

The discoveries of Pliopithecus and Dryopithecus fossils in France, combined with the opinions expressed by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and others regarding the significance of apes being present in France during the Miocene, led Lartet to become convinced that if apes had existed in the geological past, it might also be possible that humans had lived at an equally remote period. This idea was often referred to as the “geological antiquity of man” and Lartet became interested in investigating this idea. During the 1830s and 1840s, several people had found possible evidence of this. Paul Tournal in France and Philippe-Charles Schmerling in Belgium had found flint artifacts and even some fossilized human bones mixed among the bones of extinct Pleistocene animals during their excavations of caves. And over the course of many years of work in the river deposits along the Somme valley near Abbeville, Jacques Boucher de Perthes amassed a substantial collection of Pleistocene animal fossils associated with stone artefacts. The idea of the geological antiquity of humans was controversial and the evidence was contested, but as the evidence increased more people began searching for stone tools in what were called “diluvial” (Pleistocene) deposits. Since many of these early discoveries were made by amateur researchers, the accurate identification of the extinct animal species that were found with human artifacts was an important way to determine their geologic age. Thus, Lartet’s expertise in paleontology would be invaluable in identifying these fossils and thus proving the geologic age of the flint artifacts associated with them.

In 1845, Lartet had written that he thought human fossils might be found in the Tertiary deposits he was excavating, although he had not yet found any human bones or artifacts in the course of his excavations (Lartet 1845). Given the problems involved with cave deposits and the mixing of strata due to the action of water in forming cave deposits, Lartet wanted to focus instead on geologic deposits like those studied by Boucher de Perthes in the Somme valley. His views on the possible geological antiquity of humans were informed by his understanding of the history of the earth and his interpretation of the fossil record. Many French paleontologists supported the ideas of Georges Cuvier, whose catastrophist theory of earth history relied upon repeated cataclysms in the past to explain the stratigraphic layers of rock and the discontinuities in the fossil record. According to this theory, God had created various species of plants and animals, many of which became extinct due to a cataclysm, and these were succeeded by new species of plants and animals that were created. The history of life on earth is a record of successive creations and destructions, where humans only appeared on earth after the last great cataclysm that caused the extinction of so many of the Ice Age animals. According to this scenario, humans did not exist during the Pleistocene. A dramatically different interpretation of the fossil record was represented by the supporters of Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and other naturalists who argued that species had changed over time, so the fossil record was not the product of successive creations and extinctions but instead the gradual emergence of new species over time by evolutionary processes. Yet, other naturalists explained the appearance of new species of animals in the fossil record of a region through the migration of already existing animals from some distant part of the earth into that region.

Lartet was aware of these competing theories, but his own interpretation of the fossil record appears to have been influenced by Henri de Blainville. In his massive work titled Ostéographie, published in sections between 1839 and 1864, de Blainville rejected the catastrophist idea of successive creations and extinctions, arguing instead that there had only been one creation of plants and animals at the beginning of the world. However, unlike Lamarck and the other supporters of transformist (evolutionary) theories, de Blainville believed that all the species that have ever existed were created at the beginning of the world and no new species had evolved. Over time, however, many species disappeared from the world, becoming extinct. There had originally been a complete series of animal creation, at the beginning of the world, of which, the present world only contains the depleted remnants. Lartet, like de Blainville, believed that fossils allow paleontologists to fill in the gaps left by the extinction of animals and therefore to reconstruct the complete series of animal creation that existed at the beginning of the world. Lartet also agreed with de Blainville that extinction did not occur abruptly as a result of cataclysms, but occurred gradually (Lartet 1845; see also Goulven 1993).

Furthermore, Lartet resorted to migrations of animals to explain the appearance of new species of animals in France during the transition from the Tertiary through the Quaternary periods. He had particularly examined the animal species living in Europe from the Miocene, Pliocene, Pleistocene, and into the modern world and in February 1858 he presented a paper on this subject before the Académie des Sciences. Lartet identified two distinct Quaternary faunas in the European fossil record. He argued that many European mammals originated from Tertiary species living in Asia and Pleistocene species living in Europe, and that while some Pleistocene species became extinct at the end of the Ice Age, others simply migrated north to the artic where they continue to live today. Lartet rejected the catastrophist notion of a large and rapid cataclysm that separated the Pleistocene from the present world. Instead, he believed a long transition period linked the two geologic periods, evidenced by the persistence of some species such as terrestrial and freshwater mollusks (Lartet 1858). An important implication of this theory was that if many species of animals had survived the transition from the Pleistocene to the present world, there was no reason to think that humans could not also have lived through the transition from the Ice Age world to the modern world.

By the late 1850s, Lartet was increasingly becoming involved in the growing scientific debate over the geological antiquity of humans. In 1851, Lartet’s friend and colleague Jean-Baptiste Noulet, who taught medicine and natural history in Toulouse, had discovered Pleistocene animal fossils associated with stone artifacts at Clermont-le-Fort. Because of the controversies generated by other similar discoveries, Noulet delayed announcing these discoveries until February 1853 at a meeting of the Académie des Sciences de Toulouse and did not publish an account of them until 1860. But Lartet was aware of Noulet’s provocative discoveries. The debate over Ice Age humans reached its culmination when British geologists conducting careful excavations at Brixham cave, in Devonshire in the south of England, found incontrovertible evidence of flint artifacts associated with Pleistocene animal fossils during their work in 1858 and 1859. Some of the British geologists involved in the Brixham excavations traveled to France to examine the artifacts and fossils that Jacques Boucher de Perthes had collected at Abbeville in the Somme valley and came away convinced that the evidence from Britain and France demonstrated that humans had lived during the Pleistocene. Lartet began corresponding with Boucher de Perthes in 1859 and travelled to Abbeville to inspect his collection of artifacts.

Lartet examined the flint axes that Boucher de Perthes had found and concluded that they were most likely used to cut the flesh from large animals. Consequently, Lartet inferred that it might be possible to observe cut marks left on some animal bones found associated with these artifacts. Prompted by this thought, Lartet examined the collection of Pleistocene animal fossils at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle and did indeed find cut marks left on the bones of rhinoceros, elk, and auroch that matched the kinds of flint axes he had seen in Boucher de Perthes’ collection. Lartet considered this to be additional proof that humans had indeed lived during the Pleistocene. With a substantial quantity of new evidence in hand proving the geological antiquity of humans, Lartet sent a paper to the Société Géologique de France describing his discovery of cut marks on fossil bones (Lartet 1860a) and on 19 March he read a paper before the Académie des Sciences titled “Sur l’ancienneté géologique de l’espèce humaine dans l’Europe occidentale” (On the Geological Antiquity of the Human Species in Western Europe). However, the permanent secretary of the Académie des Sciences, geologist Elie de Beaumont, refused to publish the paper and only the title appeared in the Academy’s Memoires (Lartet 1860b). This was because de Beaumont continued to reject the evidence for Ice Age humans and because the subject remained controversial, both among scientists and the general public. Lartet was so infuriated by this that he published the paper in the journal Annales des sciences naturelles (Lartet 1860c) and had an English version of the paper published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society in Britain (Lartet 1860d). When Lartet presented a second paper on the subject to the Académie des Sciences on 23 April it was published (Lartet 1860e).

In the midst of this, Lartet also published a monumental memoir on the dentition of fossil proboscidians and on the geographical and stratigraphic distribution of their remains in Europe Lartet (1859). Given the great excitement and discussion generated by the recent evidence for Ice Age humans, he also hoped to excavate new sites in order to obtain additional facts. Alfred Fontan, the fossil collector who discovered the Dryopithecus fossils that Lartet had studied in 1856, found Pleistocene animal fossils along with arrowheads and other artifacts made from animal bone in a cave at Massat, in Ariège, and he wrote Lartet about this in 1858 (Fontan 1861). Following this lead, Lartet went to Massat in September 1860 and began new excavations in the cave. While work at Massat progressed, Lartet decided to also visit Aurignac, located nearby in Haute-Garonne. Lartet had long known about some remarkable discoveries made there. In 1852, a quarry worker named Jean-Baptiste Bonnemaison was surprised while digging in a rock shelter at Aurignac when he unearthed some animal fossils along with seventeen human skeletons in what apparently had been buried in a Paleolithic tomb. The local mayor had the skeletons removed and buried in the parish cemetery but Lartet learned of them and was curious. Bonnemaison accompanied Lartet on the visit to Aurignac in October 1860 to show him where he found the bones in the rock shelter. Unfortunately, no one in the village could remember exactly where the human skeletons had been buried, but Lartet initiated a new excavation of the rock shelter and soon unearthed flint artifacts along with some new human bones, carved reindeer antlers, what appeared to be the remains of a dwelling, and fossilized bones of cave bear, mammoth, cave hyena, and woolly rhinoceros.

While Lartet was working at Massat and Aurignac, he was visited by the wealthy English banker Henry Christy. Christy was born in Kingston-on-Thames in 1810. His father, William Miller Christy, was a wealthy Quaker who owned a hat making firm and became a banker. Henry Christy followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a director of the London Joint-Stock Bank, but he was also a prominent philanthropist with a strong interest in ethnology and archaeology. He was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, a member of the Ethnological Society of London, and he was elected a member of the Geological Society of London in 1857, the same year Lartet became a member. From the age of forty he travelled widely, especially to North America, to expand his ethnological collections. Christy closely followed the new discoveries from France and Britain pertaining to Ice Age humans, so he decided to observe Lartet’s work at Massat and Aurignac. Almost at once, Christy decided to provide funds to support Lartet’s excavations and so began a collaboration between Lartet and Christy that led to the systematic excavation of a number of Paleolithic caves and rock shelters along the Vézère valley, in the Dordogne region.

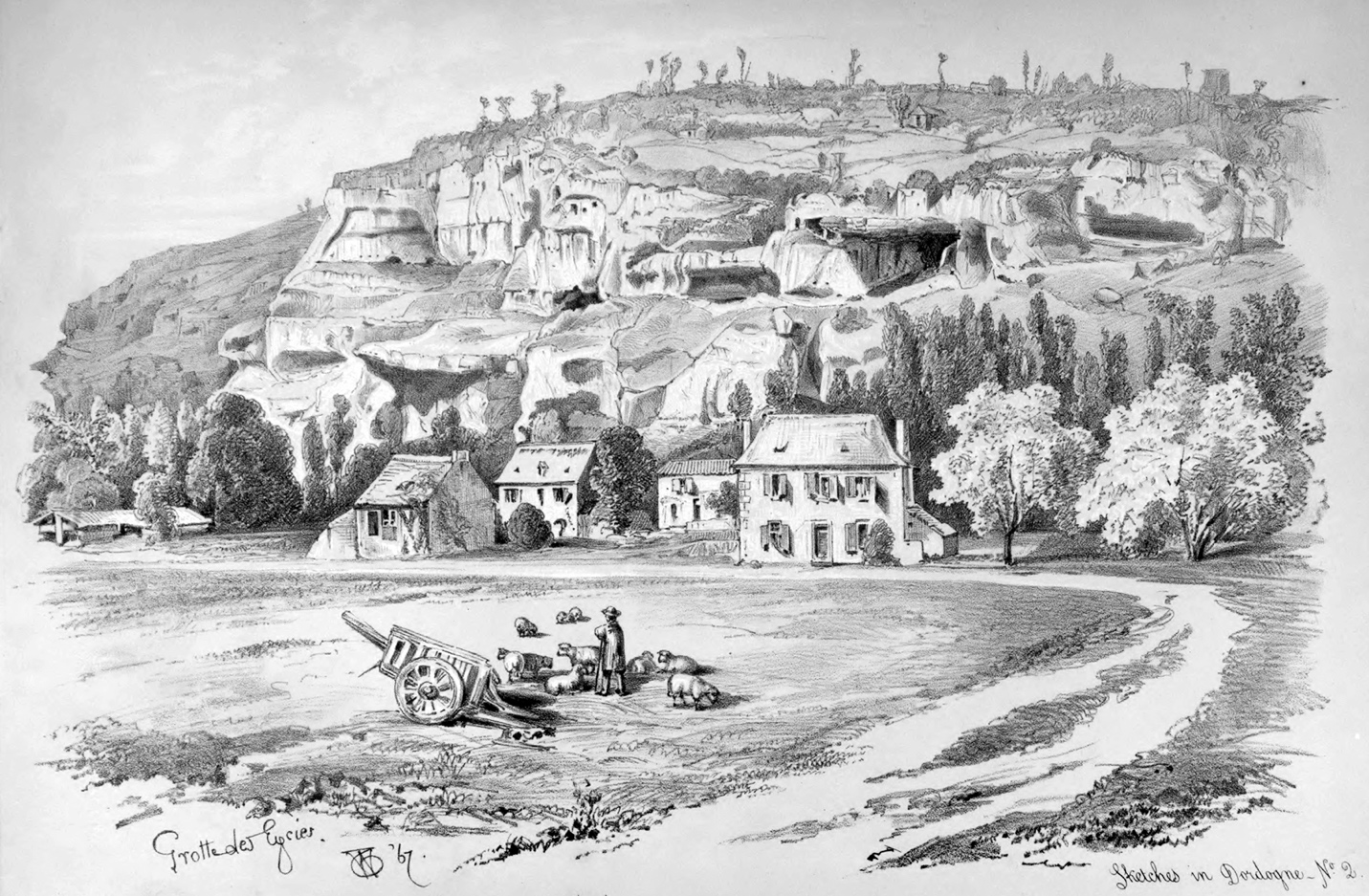

The excavations at Massat not only produced Pleistocene animal bones and flint artifacts, but Lartet also recovered a perforated reindeer antler engraved with the image of a bear. Then, in the nearby Caverne de Savigné he found a reindeer bone engraved with two animal figures. These were clearly remarkable finds, but at this point Lartet did not emphasize the significance of these specimens of Paleolithic art, but instead focused on their value as further evidence for the geological antiquity of humans (Lartet 1861). Through their correspondence with Jacques Boucher de Perthes, Lartet and Christy learned of a collection of artifacts and fossil bones from the region that had been accumulated by the Vicomte Alexis de Gourgue in his chateau at Lanquais, near Bergerac. Lartet met de Gourgue at a scientific meeting held in Bordeaux in October 1861 and began corresponding with him in 1862, sending him some specimens from Aurignac and Massat. Another important event occurred in 1862 when Lartet saw an interesting block of breccia embedded with animal bones and flint tools that had been sent from Les Eyzies to the Parisian antiquities dealer Jules Charvet. Prompted by this, Lartet and Christy traveled to Les Eyzies in August 1863 to search for possible excavation sites. Information from local residents led them to excavate the rock shelters and caves at Les Eyzies, Gorge d’Enfer, Laugerie-Haute, Le Moustier, La Madeleine, Laugerie-Basse, and Le Pech de l’Aze during 1863 and 1864.

These excavations produced huge quantities of animal fossils, hundreds of flint artifacts as well as bone artifacts, including needles made from reindeer antler, fish hooks and harpoons, and bone arrowheads. Lartet and Christy also unearthed ornaments made from perforated teeth and shells and remarkable examples of Paleolithic art. These latter consisted of engraved and sculpted figures of mammoth, reindeer, and ibex found at Les Eyzies, La Madeleine and Laugerie-Basse. Lartet and Christy found a perforated bone pendant engraved with the image of a wolverine at Les Eyzies. Lartet recognized that these works of art did not conform to the expectations of many archaeologists regarding the cultural and intellectual capacities of Paleolithic peoples. Prehistoric peoples were generally thought to possess only a “primitive” culture. He explained this apparent contrast by suggesting that “progress and perfection in the arts do not always manifest themselves in conformity with chronological gradations” (“le progrès et la perfection dans les arts ne se manifestent pas toujours en conformité des gradations chronologiques”) (Lartet and Christy1864: 264). Christy read a paper to the Ethnological Society of London on 21 June 1864 and he suggested that “it is not surprising to find there was leisure for less necessary work, and that spare time found occupation in works of pleasure, instanced in the sketches and sculpture before alluded to” (Christy 1864: 368).

The English geologist Hugh Falconer and the French paleontologist Édouard de Verneuil were visiting Lartet and Christy’s excavations in May 1864 when a piece of mammoth ivory with the image of a mammoth engraved on it was unearthed at La Madeleine, which provided undeniable proof that humans coexisted with mammoths during the Pleistocene (Lartet 1865). This remarkable artifact was examined and verified by several eminent scientists, including Henri Milne-Edwards, Armand de Quatrefages, and Augustus Wollaston Franks. At Laugerie-Basse, Lartet and Christy found reindeer antlers engraved with or sculpted into images of animals such as the auroch, and harpoons carved with figures of a horse and a reindeer. These are now dated from 16,000 to 12,000 years ago. The excavations at La Madeleine also produced some fossil human bones, including a fragment of a frontal bone from the cranium, half a mandible, and several limb bones but due to the lack of signs of burial Lartet and Christy were cautious about making claims about the geologic age of these bones until the later discoveries of Paleolithic human skeletons at Cro-Magnon and at Laugerie Basse. From the variety of artifacts found during their excavations in the Vézère valley, Lartet and Christy demonstrated that people living there had sewed clothing; made jewelry; engraved stone, bone, and antler; and possessed a certain degree of culture. They also noted that the flint artifacts found in the cave at Le Moustier differed notably from the stone artifacts found at the other sites.

Early in the course of the excavations in the Vézère valley, Lartet had sought a way to chronologically organize the sites and the artifacts that were being found at Pleistocene sites across Europe. Given the vast periods of time involved and his knowledge of the changes in climate and the resulting migrations of animals during the Pleistocene, Lartet believed it was possible to construct a relative chronology based upon the predominant animal species found at different sites. This was also based, to some extent, on the stratigraphic evidence from the deposits at Massat and Aurignac, where different animal species were found in different layers. On the basis of this evidence, Lartet proposed a series of four distinct chronological periods for the Pleistocene archaeological sites of Europe: l’âge de l’Ours des cavernes, l’âge de l’Eléphant et du Rhinocéros, l’âge du Renne, et l’âge de l’Aurochs (Cave Bear Age, Elephant and Rhinoceros Age, Reindeer Age, and Auroch Age) (Lartet 1861). The French prehistoric archaeologist Gabriel de Mortillet rejected Lartet’s chronological scheme on the basis of several factors. First, he argued that the animal species upon which Lartet’s chronology was based are found throughout the Paleolithic, whereas stone artifacts were more variable and provided a stronger foundation for a relative chronology. Second, he argued that species abundance would likely be affected by the geographical location and the type of site (whether it was a cave or an open-air site). Over the next few decades, de Mortillet constructed a relative chronology of the Paleolithic based upon types of artifacts, which he thought provided the best means of tracing the stages of human development (de Mortillet 1869; 1872; 1883).

Many French and British scientists, including John Lubbock, traveled to the Vézère valley to observe the excavations carried out by Lartet and Christy. Lartet and the zoologist, Henri Milne-Edwards, in turn, visited the Paleolithic site of Bruniquel in January 1864 to inspect two engraved pieces of bone found during excavations by Vicomte de Lastic in 1863. Meanwhile, as Lartet continued working in the caves and rock shelters of the Vézère valley, Henri Christy travelled to Belgium in April 1865 to examine some recently discovered caves. Unfortunately, he caught pneumonia as a result and while traveling with Lartet in May 1865 Christy died. Christy’s death and Lartet’s own poor health brought the tremendously productive excavations in the Vézère valley to an end. Christy and Lartet had begun work to publish a comprehensive account of their excavations, titled Reliquiae Aquitanicae, in 1865 and Christy left money in his will to ensure the completion of the work. However, Lartet died before the book was finished and completion of the project fell to his son Louis and English geologist, Thomas Rupert Jones. When Reliquiae Aquitanicae was finally published in full in 1875 it contained papers on the geology, paleontology, and the archaeology (including Paleolithic art) of the prehistoric sites excavated by Lartet and Christy. Leaving the continued excavation of the Paleolithic sites of the Vézère valley to a new generation of scientists, Lartet traveled to Spain with his son Louis in 1865. Louis examined caves in Álava and the Cameros Mountains, notably the caves at Castilla la Vieja (Vieille-Castille), which contained prehistoric artifacts, but ill health prevented his father from participating in this work.

Napoleon III passed a decree on 8 March 1862 for the creation of an archaeological museum to be located in the château at Saint-Germain-en-Laye. On the instigation of Jean-Baptiste Verchère de Reffye, the director of Napoleon III’s artillery workshop at Meudon and a keen enthusiast of archaeology, Lartet was appointed in 1865 to be a member of a commission responsible for organizing the museum. Other members of the commission included the archaeologist Alexandre Bertrand, who became the museum’s first director, and members of the Commission de Topographie des Gaules. The museum, originally called the Musée des Antiquités Gallo-Romaines, was officially opened in 1867 as the Musée des Antiquités Celtiques et Gallo-Romaines because its collections rapidly expanded beyond just the Gallo-Roman period. In 1879, the name of the museum was changed to the Musée des Antiquités Nationales (Museum of National Antiquities). Lartet played an important role in organizing the museum’s prehistoric gallery when it first opened.

Lartet was now not only recognized as a renowned paleontologist but also as an important researcher of Paleolithic archaeology and his expertise was often sought. When archaeologists Henry de Ferry and Adrien Arcelin found possible Paleolithic artifacts and human skeletons at Solutré, they requested Lartet’s assistance in interpreting the finds from the site. Lartet traveled to Solutré and afterwards maintained correspondence with Ferry and Arcelin. Lartet chaired the Stone Age Commission at the Exposition Universelle, which was held in Paris in 1867. In this role he collaborated with archaeologists Gabriel de Mortillet and Émile Cartailhac on organizing the exhibits of prehistoric artifacts, which included many of the animal fossils and Paleolithic artifacts that he had unearthed in the Vézère valley. He also served as president of the Congrès International d’Archéologie et d’Anthropologie Préhistorique (International Congress of Prehistoric Archaeology and Anthropology), which also met in Paris in 1867. One of Lartet’s last publications was an innovative paper where he investigated some of the anatomical changes that had occurred in certain groups of animals from the Tertiary to the present day. He collected imprints of the brains from animal fossils and by studying them concluded that the further back we trace mammals in geological time, the more the volume of their brain is reduced in relation to the volume of their head and the total dimensions of their body. Likewise, the convolutions are more numerous and the cerebellum is more completely covered by the brain as we approach modern times. He concluded from this that there had been progress in animal intelligence over time (Lartet 1868).

During the years that Lartet lived in Paris, he held informal meetings with friends, students, and colleagues every Wednesday afternoon in his home on rue Guy-de-Labrosse. When Vicomte Adolphe d’Archiac Desmier de Saint-Simon, professor of paleontology at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, died in 1868, Lartet was selected to succeed him at the Museum. Lartet was officially appointed to the position in March 1869, but he was unable to undertake his duties because of his illness, he suffered from neuralgia for some time. The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 led Lartet to leave Paris and return to Gers in August 1870. The war affected him deeply, especially seeing his son Louis being mobilized for military service, and many of his friends later claimed that the war hastened Lartet’s death.

During the course of his career, Lartet was a member of many prominent scientific societies and institutions. He was a member of the Société Géologique de France (Geological Society of France) and served as its president in 1866. He was elected a member of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (Anthropology Society of Paris) in 1863. He was also a member of the Société d’Histoire Naturelle de Toulouse, of the Académie des Sciences et Belles Lettres de Toulouse, and of the Société Philomathique de Paris. In addition, he was a member of the Société Ramond, which was founded in 1865 in Bagnères-de-Bigorre for the study of mountains and the scientific and ethnographic study of the Pyrenees. Lartet was also a member of many foreign scientific societies, including being elected a foreign member of the Geological Society of London in 1857. He was also a member of several commissions, including the Commission de Topographie des Gaules, the Commission Scientifique Internationale, and the Commission de Statistique du Gers. Lartet received several honors in recognition of his scientific achievements. He was an made a Knight of the Légion d’Honneur in 1838 and an Officer of the Légion d’Honneur in 1867. He was also made a Chevalier de l’Ordre Royal de l’Etoile Polaire.

Édouard Lartet died of a stroke on 28 January 1871 at the family home of La Bernisse in Seissan, Gers. Specimens that Lartet collected are held in many prominent museums and private collections, including the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de Toulouse, the Musée des Antiquités Nationales, the British Museum in London, and at the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. The private papers of Édouard Lartet and Louis Lartet are held at the Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire de Toulouse. The scientific papers of Édouard and Louis were acquired by the medicine-science section of the University Library of Toulouse around 1902, most of them during the acquisition of Louis Lartet’s library. Almost all of these documents fortunately escaped the fire which ravaged the medicine-science section of the Toulouse University Library in 1910 because they were kept in the librarian’s office.

Selected Bibliography

“Lettre à Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, sur plusieurs gisements d’ossements fossiles dans le département du Gers.” Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 4 (1834): 342-344.

“Annonce de la découverte d’une mâchoire de Singe fossile à Sansan (Gers).” Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 1 (1836-37): 92-96.

“Note sur les ossements fossiles des terrains tertiaires de Simorre, de Sansan, etc., dans le département du Gers, et sur la découverte récente d’une mâchoire de singe fossile.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 4 (1837a): 85-93.

“Nouvelles observations sur une mâchoire inférieure fossile, crue d’un singe voisin du gibbon, et sur quelques dents ossements attribués à d’autres quadrumanes.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 4 (1837b): 583-584.

“Considérations sur le Diluvium sous-périnéen: lettre de M. Lartet à M. Arago.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 6 (1838): 377-382.

“Considérations géologiques et paléontologiques sur le dépôt lacustre de Sansan, et sur les autres gisements fossiles appartenant à la même formation dans le département du Gers.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 20 (1845): 316-320.

Notice sur la colline de Sansan, suivie d’une récapitulation des diverses espèces d’animaux vertébrés fossiles, trouvés soit à Sansan, soit dans d’autres gisements du terrain tertiaire du miocène dans le bassin sous-pyrénéen. Auch: J.A. Portes, 1851.

“Note sur un grand singe fossile qui se rattache au groupe des singes supérieurs.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 43 (1856): 219-223.

Albert Gaudry and Édouard Lartet, “Sur les résultats des recherches paléontologiques entreprises dans l’Attique sous les auspices de l’Académie.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 43 (1856): 271-274.

“Sur les migrations anciennes des mammifères de l’époque actuelle.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 46 (1858): 409-414.

“Sur la dentition des proboscidiens fossiles (Dinotherium, Mastodontes et Elephants) et sur la distribution géographique et stratigraphique de leurs débris en Europe.” Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 16 (1859): 469-515.

“Note sur des os fossiles portant des empreintes ou entailles anciennes et attribuées à la main de l’homme.” Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 17 (1860a): 492-495.

“Sur l’ancienneté géologique de l’espèce humaine dans l’Europe occidentale.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 50 (1860b): 599.

“Sur l’ancienneté géologique de l’espèce humaine dans l’Europe occidentale.” Annales des sciences naturelles II Zoologie 14 (1860c): 117-122.

“On the Coexistence of Man with Certain Extinct Quadrupeds, Proved by Fossil Bones, from Various Pleistocene Deposits, Bearing Incisions Made by sharp Instruments.” Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society 16 (1860d): 471-479.

“Addition à la note sur l’ancienneté géologique de l’espèce humaine, présentée le 19 mars 1860.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 50 (1860e): 790-791.

“Nouvelles Recherches sur la coexistence de l’homme et des grands mammifères fossiles réputés caractéristiques de la dernière époque géologique.” Annales des sciences naturelles II Zoologie 15 (1861): 177-253.

Édouard Laret and Henry Christy, “Sur des figures d’animaux gravées ou sculptées et autres produits d’art et d’industrie rapportables aux temps primordiaux de la période humaine.” Revue archéologique 5 (1864): 233-267.

Milne Edwards and Édouard Lartet, “Remarques sur quelques résultats des fouilles faites récemment par M. de Lastic, dans la caverne de Bruniquel.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 58 (1864): 264-266.

“Sur de nouvelles observations de MM. Lartet et Christy relatives à l’existence de l’homme dans le centre de la France à une époque où cette contrée était habitée par le renne et d’autres animaux qui n’y vivent pas de nos jours.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 58 (1864): 401-408.

“Lettre à M. Milne Edwards relative à une lame d’ivoire fossile trouvée dans un gisement ossifère du Périgord et portant des incisions qui paraissent constituer la reproduction d’un éléphant à longue crinière.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 61 (1865): 309-311.

Reliquiae Aquitanicae: Being Contribution to the Archaeology and Paleontology of Perigord and the Adjoining Provinces of Southern France. Thomas Rupert Jones (ed.). London: Williams and Norgate, 1875.

Other Sources Cited

Henri de Blainville, Ostéographie, ou, Description iconographique comparée du squelette et du système dentaire des mammifères récents et fossiles pour servir de base à la zoologie et à la géologie. Paris: J.B. Baillière et fils, 1839-1864.

A.M.C. Duméril, M.J.P. Flourens, and H. de Blainville, “Rapport sur la découverte de plusieurs ossements fossils de quadrumanes, dans le dépôt tertiaire de Sansan, près d’Auch par M. Lartet.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 4 (1837): 981-998.

A.M.C. Duméril, M.J.P. Flourens, and H. de Blainville, “Sur l’importance des résultats obtenus par M. Lartet dans les fouilles qu’il a entreprises pour rechercher des ossements fossiles; Rapport fait en réponse aux questions adressées à ce sujet à l’Académie par M. le Ministre de l’Instruction publique.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 7 (1838): 100-106.

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, “Sur la singularité et la haute portée en philosophie naturelle de l’existence d’une espèce de singe trouvée à l’état fossile dans le Midi de la France.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 5 (1837): 35-42.

Henry Christy, “On the Prehistoric Cave-Dwellers of Southern France.” Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London 3 (1865): 362-372.

Jean-Baptiste Noulet, “Sur un dépôt alluvien, renfermant des restes d’animaux éteints, mêlés à des cailloux façonnés de la main de l’homme, découvert à Clermont près de Toulouse (Haute-Garonne).” Mémoires de l’Académie Impériale des Sciences, Inscriptions et Belles Settres de Toulouse 4 (1860): 265-284.

Alfred Fontan, “On Two Bone-caverns in the Montagne du Ker at Massat, in the Department of the Ariège.” Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society 17 (1861): 468-473

Secondary Sources

Nathalie Rouquerol and Jacques Lajoux, L’origine de l’Homme: Édouard Lartet (1801-1871). De la révolution du singe à Cro-Magnon. Villemur-sur-Tarn: Éditions Loubatières, 2021.

Nathalie Rouquerol, “Édouard Lartet sur les traces de l’homme fossile.” Pour la science (2021): 72-79.

Francis Duranthon, “Portrait de deux pionniers de la science préhistorique en pays toulousain.” Mémoires de l’Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres de Toulouse (2017): 101-114.

Nathalie Rouquerol, “”Edouard Lartet, Aurignac et l’Aurignacien.” In Harald Floss and Natbalie Rouquerol (eds.). Les chemins de l’art aurignacien en Europe/Das Aurignacien und die Anfange der Kunst in Europa. Pp. 21-36. Aurignac: Editions Museee-forum Aurignac, 2007.

Laurent Goulven, “Edouard Lartet (1801-1871) et la paléontologie humaine.” Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 90 (1993): 22-30.

Jean-Jacques Cleyet-Merle and Marie-Hélène Marino-Thiault, “Les premières fouilles de Lartet et Christy et la reconnaissance de l’homme antédiluvien en Périgord.” Paléo (Special Issue: Une histoire de la préhistoire en Aquitaine) (1990): 19-24.

Norman Clermont, “Édouard Lartet and the fine recovery of faunal samples.” Archaeozoologia 7 (1995): 73-76.

A. Algans, “Les carnets inédits d’Edouard Lartet.” Revue de Comminges 84 (1971): 4-11.

A. M. Monseigny and A. Cailleux, “Lartet, Édouard-Armand-Isidore-Hippolyte.” C. C. Gillispie (ed.), Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 7, pp. 43-44. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1981.

Edouard Lartet, sa vie et ses travaux. Bruxelles: Weissenbuch, 1872.

Ernest-Théodore Hamy, “Éloge d’Édouard Lartet.” Memoires de la Societe d’Anthropologie de Paris 1 (1873): iii-xxv.

Paul Henri Fischer, “The Scientific Labors of Edward Lartet.” Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution [1872] (1873): 172-184.