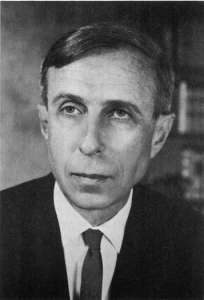

Theodore McCown (1908–1969)

Matthew Goodrum

Theodore Doney McCown was born in Macomb, Illinois, on 18 June 1908. His father, Chester Charlton McCown, was a biblical scholar and his mother was Harriett Doney. The family moved to Berkeley, California, in 1913 when Chester Charlton McCown became professor of New Testament Literature and Interpretation at the Palestine Institute of the Pacific School of Religion. In addition to his research as a New Testament scholar, Chester Charlton McCown also engaged in archaeological excavations through a long association with the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem. He was appointed a fellow there in 1920 and later served as its director in 1929 and its acting director from 1935 to 1936. While in Palestine, Chester Charlton McCown participated in the archaeological excavations at the site of Jerash (Gerasa), which he directed from 1930 to 1931. Theodore and his younger brother, Donald (who eventually became an authority on the archaeology of Persepolis and other ancient sites in Iran) were both exposed to classical and Middle Eastern archaeology during the 1920s through their father’s work.

McCown studied anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley where Alfred Kroeber was a leading figure. McCown attributed his interest in anthropology to reading Henry Morton Stanley’s book In Darkest Africa; or, the Quest, Rescue, and Retreat of Emin, Governor of Equatoria (1890). In 1928, he spent three months as an assistant to Ronald Olson excavating Indian shell mounds on the coast near Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz Island. During the summer of 1929, McCown spent three months studying the Kawaiisu Indians in the mountains of east Bakersfield, California. McCown completed his B.A. in anthropology in 1929 (with highest honors), and in 1930 he was appointed an assistant at the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem and participated in the excavations at Jerash. McCown entered the graduate program in anthropology at Berkeley in 1931 and later that year he travelled through France, Spain, Switzerland, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Hungary with the summer school of the American School of Prehistoric Research. The American School of Prehistoric Research, founded in 1921 by Charles Peabody and Yale University anthropologist George Grant MacCurdy, was created to give American students an opportunity to participate in excavations in Europe and to visit museum collections.

A significant event in McCown’s scientific career began in 1930 when he was invited to join the extensive excavations being conducted at the Wadi el-Mughara (the Valley of the Caves) at Mount Carmel, which is located about 20 km south of Haifa in what at that time was the British mandate of Palestine (now Israel). These excavations, led by British archaeologist Dorothy Garrod, were a joint project of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and the American School of Prehistoric Research. Garrod, working closely with Welsh paleontologist Dorothea Bate, began excavations at Mount Carmel in 1929. She excavated the el-Wad Cave (also known as Athlit cave) while British archaeologist Francis Turville-Petre was given the responsibility of excavating the Kebara Cave in 1930. Garrod assigned the excavation of Skhūl Cave (also known as Mugharet es-Skhūl or the Cave of the Kids) to McCown during the 1931 field season. He had joined the excavations as a field representative with the American School of Prehistoric Research and was assigned to assist Garrod. English archaeologist Mary Kitson-Clark had already completed a test excavation in Skhūl Cave in 1929 that unearthed a Mousterian deposit.

McCown’s initial excavations at Skhūl extended from 4 April to 3 June 1931, and the second excavation season was from 11 April to 17 July 1932. He uncovered three archaeological layers: Layer A contained a mixed assemblage of Natufian, Mousterian and Aurignacian material, and below this Layers B and C contained Lavalloiso-Mousterian artifacts (Garrod and Bate, 1937; McCown and Keith, 1939). More remarkably, during the course of his excavations, human bones belonging to ten individuals were unearthed. On 3 May, 1931 McCown discovered the fragmentary skeleton of a child (Skhūl I) in the Mousterian layer. But most of the fossils were discovered during his second field season. On 30 April 1932, he and his assistant Hallam Movius Jr., who at this time was a graduate student at Harvard University, discovered a partial human skeleton (Skhūl II), and the cranial fragments and mandible along with a few postcranial bones of an adult female (Skhūl III), and a nearly complete adult male skeleton (Skhūl IV) in the Mousterian layer of the cave. From their appearance, McCown believed these individuals had been intentionally buried. Then on 2 and 3 May 1932, McCown and Movius unearthed another nearly complete adult male skeleton (Skhūl V) that was found with the mandible of a wild boar, as well as a very partial adult male skeleton (Skhūl VI). Then on 13 May McCown’s team encountered a partial male skeleton (Skhūl VII) that was found near a child’s skeleton (Skhūl VIII). Finally, a partial adult male skeleton (Skhūl IX) was found on 19 May. A tenth individual, the skeleton of an infant (Skhūl X) was only recognized in 1935 while McCown was removing the bones of Skhūl VII from its matrix.

The English anatomist and paleoanthropologist Arthur Keith, who was conservator at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, was invited to study and describe the human fossils from Mount Carmel. Keith had visited Palestine in 1930 as part of a visit to Egypt and the Near East organized by the Royal College of Surgeons, and while he was in Palestine Garrod gave him a tour of the excavation sites at Mount Carmel. Keith observed the fossils encased in the rock of the cave floors and offered the facilities at the Royal College of Surgeons where the specimens could be freed from their matrix and examined. The first block containing one of the Skhūl skeletons arrived in London in 193I, and further specimens were transferred to the Royal College of Surgeons as they were unearthed. It was decided that McCown would assist Keith with the preparation and examination of the fossils. McCown and Keith presented a joint paper on the human fossils discovered so far in the Skhūl Cave at the inaugural meeting of the International Congress of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences held in London in August 1932 (McCown and Keith 1934). As work progressed, McCown published a series of papers between 1932 and 1937, some coauthored with Keith, on the fossils from Mount Carmel (McCown 1932; McCown 1933; McCown 1934a and 1934b; McCown 1936; Keith and McCown 1937).

However, by 1933 Keith’s health was declining, and he resigned as conservator at the Royal College of Surgeons to take up the role of Master at Buckston Browne Farm, in Kent, where he had a specially equipped laboratory constructed so that the work on the Mount Carmel fossils could be conducted at the residence. McCown began the laborious task of removing the fossils from the stone blocks in 1933, first at the Royal College of Surgeons, but in August 1934, McCown moved into Keith’s home at Buckston Browne Farm where they conducted their work on the fossils until 1937. During the time McCown was in England working with Keith, his research was funded by a Taussig Traveling Fellowship in Anthropology (1933-34), an Amy Bowler Johnson Traveling Fellowship (1934-35), and a fellowship from the American School of Prehistoric Research (1935-37). Increasingly, responsibility for examining the fossils fell to McCown (Keith was by this time nearly seventy years old). Dorothy Garrod and Dorothea Bate published the first volume of The Stone Age of Mount Carmel in 1937, and McCown contributed chapters on the archaeology of Skhūl Cave. Two years later, McCown and Keith completed the second volume titled The Stone Age of Mount Carmel: The Fossil Human Remains from the Levalloiso-Mousterian (McCown and Keith 1939).

In this volume, McCown and Keith described the ten partial human skeletons from Skhūl Cave and the partial female skeleton found in the Lower Mousterian layer of the nearby Tabūn Cave, and they summarized the inventory of the Upper Paleolithic human material from the el- Wad and Kebara caves, but they did not describe the Natufian material from either Shukbah or el-Wad. From the stratigraphical, archaeological, and faunal evidence from the Skhūl and Tabūn caves they argued that the hominid fossils from the two sites were approximately the same age. However, after comparing the specimens from the two caves, McCown and Keith noted morphological differences between the fossils from Skhūl and Tabūn. The Skhūl remains appeared to be more closely related to modern Homo sapiens—for example, they lack the projecting nasal region seen in the Tabūn skeleton, and the Skhūl mandibles have a chin, whereas the mandible from Tabūn does not. McCown and Keith suggested that the differences between the hominids of Tabūn and Skhūl could be due to an evolutionary progression. Their analysis of the Mount Carmel fossil remains indicated a population in the “throes of evolution” with characteristics of both modern humans and Neanderthals being present in the fossils. They argued that the fossils represented a population that was evolving from Neanderthal to Cro-Magnon. They suggested that the Tabūn specimens were older and more primitive, while the Skhūl specimens were more recent and more advanced. Significantly, they rejected an alternative hypothesis, that the skeletons might reflect hybridization between two anatomically divergent populations.

McCown’s interpretation of the fossils from Skhūl and Tabūn sometimes differed from Keith’s, and his interpretation of them changed in later years. He later came to view the Tabūn and Skhūl fossils as representing a single polymorphic population rather than as different hominid species. In his early publications, he already argued that the fossils should be viewed as belonging to a group of individuals that displayed considerable variability, noting that members of a single species are rarely morphologically identical. However, since McCown was the junior scientist, Keith’s views prevailed in their 1939 monograph. Following common practice at the time, they named these fossils Palaeoanthropus palestinensis, which they considered a local form of Neanderthal, but few scientists adopted the name or the new species. Today paleoanthropologists consider the Skhūl fossils to be older than the Tabūn specimens and to represent early Homo sapiens. Importantly, McCown also argued that the Skhūl skeletons had been intentionally buried. This was at a time when debate raged over the question of whether Neanderthals buried their dead.

In addition to this work, McCown was also completing his dissertation research. He obtained permission from the Government of Palestine to send the Natufian skeletons from Mount Carmel to Berkeley for examination, and McCown returned to Berkeley in 1938. McCown received his Ph.D. in 1939, under the direction of Alfred Kroeber, with a dissertation titled The Natufian Crania from Mount Carmel, Palestine, and Their Inter-relationships. It is primarily a study of the Natufian crania from el- Wad Cave but also includes a brief section on two adult crania from Shukbah Cave. McCown began teaching in the Anthropology Department at Berkeley in 1938 as an Instructor while he was still completing his Ph.D.. He was appointed Assistant Professor in 1941 and was promoted to Associate Professor in 1946 and to Full Professor in 1951. He served as acting chair during the 1948-49 academic year and as department chair from 1950 to 1955. McCown created the program in physical (biological) anthropology at Berkeley soon after joining the faculty, and while at Berkeley, McCown directed eighteen Ph.D. students and served on the committees of numerous others. This was at a time when Earnest Hooton at Harvard University and Wilton Krogman at the University of Pennsylvania were among the few professors training physical anthropologists in the United States. Additionally, McCown served as curator of physical anthropology at the university’s Lowie Museum beginning in 1948. He also held a joint position in the Department of Criminology from 1948 to 1950, and he taught forensic anthropology at a time when there were only a few other practitioners in this applied field of anthropology. Many of the graduate students whom he supervised went on to form the first generation of practicing forensic anthropologists in the United States. McCown was involved in university administration and served as associate dean of the College of Letters and Science from 1956 to 1961.

McCown conducted archaeological excavations in the mountainous region of Huamachuco and Cajabamba, in Peru, under the auspices of the Institute of Andean Research from August 1941 to March 1942 and again in 1945. These excavations led McCown to identify two periods of occupation at these sites (Middle Huamachuco and Late Huamachuco) represented by distinct architectural styles in buildings and by distinctive pottery styles. He also examined human skeletons that Alfred Kroeber had collected from Aramburu and other Peruvian sites as part of an expedition for the Field Museum in Chicago (McCown 1945). McCown’s academic work was interrupted by World War II. During his military service from 1942 to 1945 he was assigned duty to the Sixth Army Quartermaster Corps, Graves Registration Service, based at the San Francisco Presidio. His assignments included personal identification of war dead. This served as a stimulus to his postwar interest in practicing and teaching forensic anthropology. Following the war, from 1948 to 1950, McCown was a consultant for the military on a project relating to research on prostheses that he had begun in 1945.

At the end of the war, McCown returned to Berkeley and his anthropological work. He married Elizabeth Ann Richards in 1946. She had studied anthropology at Berkeley and then completed a Master’s degree in physical anthropology in 1946 at the University of Chicago, where she studied under Walter Krogman. In 1948 McCown began a project to analyze the collection of California Indian skeletons that Alfred Kroeber had collected earlier in the century. He also conducted a number of prominent forensic investigations that led to the identification of Junipero Serra (1715-1784) at the Franciscan Mission in Carmel, California; the identification of Juan Bautista de Anza (1735-1788), the founder of San Francisco, whose remains were exhumed in Arizpe, Mexico; and the negative identification of remains reputed to be those of the American aviatrix Amelia Earhart that were found on a Pacific island. McCown led two expeditions to the Narmada Valley of India, the first in 1958 and the second from 1964 to 1965, where he was accompanied by his wife Elizabeth. During the 1958 season, he collaborated with researchers at the Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute located in Poona. In the Narmada Valley, he established the stratigraphic contexts of alluvial deposits that contained Paleolithic stone tools dating to the Middle Pleistocene. During the 1964-1965 expedition, McCown was assisted by Berkeley graduate student George Shkurkin and S. C. Supekar, a graduate student at Deccan College. In the course of their excavations, they collected Acheulean artifacts at Mahadeo Piparia in the Narmada Valley.

McCown’s research and teaching combined biological anthropology and cultural anthropology. He believed that “man is a part of ‘brute creation,’ that the hypotheses which are valid for the processes of organic evolution apply as well to man as to other animals.” He was a member of several prominent professional societies. These include the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Society for American Archaeology, the American Society of Physical Anthropology, and the American Society for Human Genetics. He was a Fellow of the American Anthropological Association as well as a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. McCown presented a paper on hominid taxonomy at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology held in 1950 (McCown 1951). This meeting was significant because it marked an important step in integrating the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis into paleoanthropology. He also published an influential paper on the training and education of physical anthropologists (McCown 1952). McCown died from a heart attack in Berkeley on 17 August 1969.

Selected Bibliography

“A Note on the Excavation and the Human Remains from the Mugharet es-Sukhul (Cave of the Kids), Season of 1931.” American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 8 (1932): 12-15.

“Fossil Men of the Mugharet es-Sukhul, near Athlit, Palestine, Season of 1932.” American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 9 (1933): 9-15.

Theodore McCown and Arthur Keith. “Palaeanthropus palestinus.” Proceedings of the First International Congress of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences (1934): 48.

“Discovery of a Mousterian Cemetery on Mount Carmel.” Proceedings of the First International Congress of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences (1934a): 48-50.

“The Oldest Complete Skeletons of Man” (with a note by Sir Arthur Keith). American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 10 (1934b): 13-19.

Theodore McCown and Arthur Keith. “The Mousterian People of Palestine: their anatomy.” Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Sectional Transactions, 1935 pp. 41-42.

“Mount Carmel Man.” American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 12 (1936): 131- 140.

Arthur Keith and Theodore McCown, “Mount Carmel Man. His Bearing on the Ancestry of Modern Races.” American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 13 (1937): 5-15.

“Chapter VI. Mugharet es-Skhūl. Description and Excavations.” In D. A. E. Garrod and D. M. A. Bate, The Stone Age of Mount Carmel: Excavations at the Wady el-Mughara. Vol. I. Pp. 91-107. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937.

Theodore McCown and Arthur Keith, The Stone Age of Mount Carmel: The Fossil Human Remains from the Levalloiso-Mousterian. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1939.

“The Antiquity of Man in the New World.” American Antiquity 7 (1941): 203-213.

“Pre-Incaic Huamachuco; Survey and Excavations in the Region of Huamachuco and Cajabamba.” University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 39 (1945): 223-400.

“Genus Palaeoanthropus and the Problem of Supra-specific Differentiation among the Hominidae.” Cold Springs Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology: Origin and Evolution of Man, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 15 (1951): 87-94.

“The Training and Education of the Professional Physical Anthropologist.” American Anthropologist 54 (1952): 313-317.

Theodore McCown and K. A. R. Kennedy (eds.), Climbing Man’s Family Tree: A Collection of Writings on Human Phylogeny, 1699-1971. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1971.

The Theodore D. McCown papers are located in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Collection number: BANC MSS 86/3 c CARTON 1; BANC MSS 86/3 c CARTON 2; BANC MSS 86/3 c; BANC MSS 86/3 c

Dortothy Garrod and Theodore McCown correspondence (letters sent between 1930 and 1954) are held at Cambridge University Library.

Other Sources Cited

Dortothy Garrod and Dorothea Bate, The Stone Age of Mount Carmel: Excavations at the Wady el-Mughara. Vol 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937.

Secondary Sources

E. A. Hammel, “Theodore Doney McCown, June 18, 1908-August 17, 1969.” Papers of the Kroeber Anthropological Society 41 (1969): 1-7.

Sheilagh T. Brooks, Theodore D. McCown, 1908-1969. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 32 (1970): 165-166.

K. A. R. Kennedy, (1997). “McCown, Theodore D(oney) (1908-1969).” In Frank Spencer (ed.), History of Physical Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 2, pp. 627-629. New York: Garland.

Kenneth Kennedy and Sheilagh T. Brooks, “Theodore D. McCown: A Perspective on a Physical Anthropologist.” Current Anthropology 25 (1984): 99-103.

Kenneth Kennedy and Elizabeth Langsthroth, “Recent Recovery of Unpublished Field Notes of Theodore D. McCown’s Paleoanthropological Explorations in the Narmada River System, India, 1964 –1965.” Asian Perspectives 50 (2013): 132-143.

I. De Groote, C. Stringer, T. Compton, B. Kruszynski, and S. Bello, “Sir Arthur Keith’s Legacy: Re-discovering a lost collection of human fossils.” Quaternary International 337 (2014): 237-253.