Ralph Solecki (1917–2019)

Matthew Goodrum

Ralph Stefan Solecki was born on 15 October 1917 in Brooklyn, New York, to Polish immigrants. His father, Casimir Solecki, sold insurance, and his mother, Mary (née Tarnowska), was a homemaker. While his parents named him Stefan Rafael, he was known throughout his career as Ralph. Solecki’s interest in archaeology began when he was about ten years old after he read newspaper reports of the treasures that the British Egyptologist Howard Carter had retrieved from the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun. In 1931 his family bought a house in Cutchogue, on Long Island’s North Fork, in New York, and soon thereafter Solecki began searching the farm fields near his home for Native American arrowheads and other artifacts. Solecki attended Newtown High School in Elmhurst, Queens, and after graduating in 1936, he enrolled in the City College of New York where he received a B.S. degree in geology in 1942. Throughout these years, he had been engaged in a number of productive archaeological excavations. Solecki and his childhood friend Stanley Wisnewski, who was also an aspiring archaeologist, often spent time collecting Native American artifacts along Maspeth Creek, on Long Island. While still a student in high school, Solecki read an article about a log fort built in the 1630s by the Corchaug, a local Native American tribe, with the help of European settlers. The precise location of the Fort Corchaug site had been lost to time so during the summer of 1935, Solecki began searching for remains of the fort. An amateur archaeologist suggested that he look on the west side of Downs Creek, which lay just east of the Solecki family home. He began digging at the site in 1936 and found Native American and Dutch trade goods. His most extensive excavations of the site were conducted from 1946 to 1948 and formed the basis of his Master’s thesis in archaeology at Columbia University. From his excavations of Fort Corchaug, Solecki concluded that it had served as a defense against attack from New England tribes who traveled to eastern Long Island to collect shells as well as a trading post where wampum was manufactured and traded to the Dutch in New Amsterdam from the 1630s to the 1660s.

Solecki was one of the members of the Committee on American Anthropology of the Flushing Historical Society that conducted excavations of the Fort Massapeag site from 1937 to 1938. Fort Massapeag, located in the town of Oyster Bay on Long Island, was a Dutch fortified trading post constructed around the 1650s to facilitate trade with the local Native American population. The excavation team, which also included Carlyle Sheeve Smith who was an archaeology student at Columbia University and a friend of Solecki, mapped the earthworks of the fort and found Native American artifacts from the Late Woodland period, including pottery and wampum. In 1939 Solecki again joined other members of the Flushing Historical Society to excavate a shell pit at the head of Hawtree Creek, an arm of Jamaica Bay, located in Queens County, New York. During the excavation they found pottery fragments and stone artifacts along with a Native American grave dating from the Late Woodland Period. The grave contained the skeleton of an adult woman and the partial skeleton of an infant, which were donated to the American Museum of Natural History in 1947. To this point in his life, Solecki’s archaeological experience was limited to the region around his home in New York, but that changed when he spent three summer field seasons conducting archaeological excavations in Nebraska, the first in 1939 working with Carlyle Shreve Smith, the second in 1940 working with Robert Cumming, Jr., and the last in 1941 working with Marvin (Gus) Kivett.

Like many other young men of his generation, Solecki’s life took a dramatic turn with the United States’ entrance into the Second World War. He served in the army in Europe from 1942 to 1945 and was wounded. At the end of the war, Solecki returned to New York where he enrolled at Columbia University in 1946 to study anthropology. While at Columbia, Solecki studied with William Duncan Strong, who was professor of American archaeology. His Master’s thesis, completed in 1950, was based upon his excavations at Fort Corchaug. From 1948 to 1949, while still a graduate student at Columbia, Solecki joined the River Basin Surveys. The River Basin Surveys were salvage archaeology surveys administered by the Smithsonian Institution. The need for such surveys was spurred by new dam construction projects. As part of the River Basin Surveys, Solecki worked at the Bluestone Reservoir, on the border of West Virginia and Virginia, where he unearthed the remains of Native American villages, mounds, rock art, and the remains of colonial forts. Solecki also worked at the West Fork Reservoir on the Monongahela River in West Virginia where he identified Native American campsites. Solecki was transferred from the River Basin Surveys to the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1949, although in this new position he still participated in projects conducted by the River Basin Surveys. Solecki conducted important excavations organized by the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Adena Mound in Natrium, West Virginia from December 1948 to January 1949 that unearthed a large number of burials and artifacts (Solecki 1953). From May to September 1949, he accompanied an expedition organized by the United States Geological Survey, the Bureau of American Ethnology, and the Smithsonian Institution to the upper Kokpowruk and Kokolik rivers in Alaska where he studied the archaeology of this area and observed the culture of the local Eskimo.

After several years of working with the River Basin Surveys and the Bureau of American Ethnology, Solecki was appointed an associate curator of archaeology at the Smithsonian Institution in 1951. He was also still a graduate student at Columbia University. His career took a significant turn in 1950 when he took a leave of absence from his duties at the Smithsonian to join a University of Michigan expedition to the Near East led by George Cameron, who invited Solecki to join the expedition. At the end of the expedition, however, Solecki remained in Iraq to independently explore the Shanidar Cave, one of forty caves he visited in the Kurdistan region. Between 1951 and 1961, he led a team of archaeologists and anthropologists that excavated Shanidar Cave and the nearby site of Zawi Chemi. Shanidar is located in the Zagros Mountains in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq. Solecki reported his desire to investigate the Shanidar cave to the Directorate General of Antiquities of Iraq, which was led by Director General Naji al Asil. Solecki eventually spent four seasons excavating at Shanidar. The first season extended throughout 1951 and was funded by the Directorate General of Antiquities of Iraq. The second season from May to August 1953 was conducted under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution and the Directorate General of Antiquities of Iraq. The third season lasted from October 1956 to June 1957. Political events during the summer of 1958 forced Solecki to postpone that planned field season until 1960. This proved to be the last season of excavations at Shanidar because the Kurdish rebellion in the country prevented further fieldwork after 1961.

Solecki’s excavations of the Shanidar Cave uncovered artifacts from four major cultural layers covering a period of about 100,000 years. From bottom to top, these consisted of a Middle Paleolithic flake-based industry classified as ‘‘Mousterian’’ (Layer D); an Upper Paleolithic blade-based industry named ‘‘Baradostian’’ (Layer C); a Mesolithic industry called ‘‘Zarzian’’ characterized by backed blades (Layer B2) and similar material associated with a group of Proto-Neolithic burials (Layer B1); and an upper layer that contained Neolithic industries and recent artifacts (Layer A). During the second excavation season at Shanidar, Solecki sent charcoal samples from hearths in the cave to the U. S. Geological Survey, and they employed the newly developed radiocarbon dating technique to date the stratigraphic layers. Solecki collected a large number of distinctive stone artifacts from Layer C that he dated to the Upper Paleolithic. The Cambridge University archaeologist Dorothy Garrod, who led the excavations of the Mount Carmel site in Palestine from 1929 to 1934, visited the Shanidar site in December 1953 especially to inspect these Upper Paleolithic artifacts. It was Garrod who suggested that these artifacts be called Baradostian, after the local mountain range.

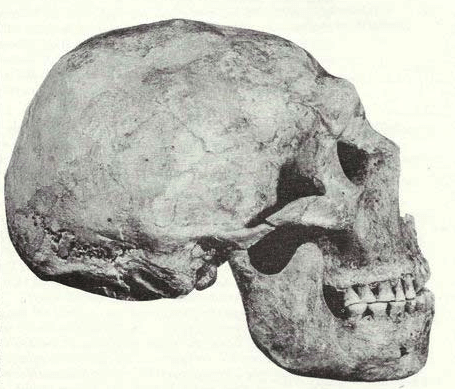

The most significant discoveries from Shanidar Cave, however, were a remarkable series of Neanderthal skeletons. The first Neanderthal material from the site was the crushed skeleton of an infant that was discovered on 22 June 1953 and is now referred to as Shanidar 7 (Solecki 1957). The Turkish anthropologist Muzaffer Şenyürek, of the University of Ankara, traveled to Baghdad at Solecki’s request to study the infant skeleton during December 1956 and January 1957 (Şenyürek 1957a; 1957b). Then during the third season’s work at Shanidar, Solecki’s team unearthed three partial Neanderthal skeletons over the period from 27 April to 23 May 1957 (Solecki 1960). George Maranjian, of Harvard University, was the physical anthropologist on the expedition during the third season, and he assisted in the excavation and preparation of the skeletons. These are now referred to as Shanidar 1, 2, and 3, and they were dated to about 40,000 years ago. It was later realized that parts of the Shanidar 3 skeleton had been discovered earlier but were not recognized as human bones at the time. Much of the Shanidar 3 skeleton was excavated during the third and fourth seasons of excavation. In June 1957, Solecki invited Thomas Dale Stewart to undertake the preparation, reconstruction, and analysis of the Neanderthal skeletons. Stewart, who was the curator of physical anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian Institution), arrived in Baghdad in October, and his work resulted in the publication of several initial reports on the Shanidar 1 skeleton (Stewart 1958; 1959).

When Solecki resumed excavations for the fourth field season at Shanidar Stewart served as the physical anthropologist on the team. On 3 August 1960, the team unearthed another Neanderthal skeleton (now designated Shanidar 4), and just a few days later on 7 August, they discovered yet another partial Neanderthal skeleton (now designated Shanidar 5). The Shanidar 4 skeleton would become famous as the flower burial. This skeleton was found lying on its side with its legs in a flexed position. Arlette Leroi-Gourhan, the paleobotanist on the expedition, discovered pollen from flowers in the grave with the skeleton, which led Solecki to propose that flowers had been buried with this individual. There was also other evidence indicating aspects of Neanderthal behavior. The Shanidar 1 skeleton belonged to an adult male, but the skeleton showed evidence of many injuries sustained during this individual’s life. These had healed but some were so severe that Solecki realized the only way this person could have survived was if other members of his community had taken care of him. Bones from several other individuals were also unearthed during this season, but it was only later that they were recognized and catalogued as Shanidar 6, 8, and 9.

During the third and fourth seasons at Shanidar, Solecki’s wife, Rose Solecki, joined the expedition team. Rose Muriel Lilien was born on 18 November 1925 in New York City, and she completed her undergraduate degree in anthropology from Hunter College in 1945. She went on to receive her Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University, where she studied under William Duncan Strong and joined Strong’s excavation team in Peru from 1952 to 1953. Ralph and Rose married in 1955, and the following year, Rose joined Ralph at Shanidar where she began excavating the nearby Proto-Neolithic site of Zawi Chemi Shanidar. This was an open-air village site located in the Shanidar valley, on the left bank of the Greater Zab River, near Shanidar Cave. There Rose Solecki discovered stone and bone artifacts dating from the period when these people were making the transition from a nomadic to a sedentary culture. During the last days of the 1960 excavation season at Shanidar, Solecki’s team discovered an undisturbed Proto-Neolithic cemetery in the B Layer at the back of the cave dating to around 10,600 years ago. The excavation of the cemetery exposed twenty-six graves that contained various grave offerings, mainly bone and stone tools and beads, as well as human skeletons. Solecki recovered the remains of thirty-five individuals; including twenty infants and children, five adolescents, and ten adults.

Solecki was forced to stop work at Shanidar due to political unrest in Iraq. The Shanidar Neanderthal skeletons (with the exception of Shanidar 3) and the skeletons from the Proto-Neolithic cemetery were sent to the Baghdad Archaeological Museum (now the Iraq Museum).1 The Shanidar 3 skeleton was sent to the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. Solecki had already completed his Ph.D. in anthropology at Columbia University in 1958. His dissertation, titled The Baradostian Industry and the Upper Palaeolithic in the Near East, focused on his archaeological discoveries in the Upper Paleolithic deposits of Shanidar Cave. The description and analysis of the Shanidar Neanderthal skeletons fell to T. Dale Stewart (Stewart 1958; 1959; 1963; 1977). However, he was unable to complete the study of all the skeletal material, so in 1976 Erik Trinkaus, who was a professor of anthropology at Harvard University at the time, took over the study of the fossils (Trinkaus 1983).

Solecki’s discoveries at Shanidar were significant for a number of reasons. They were the first Neanderthals specimens found in this part of Eurasia. More consequential were the conclusions he drew from these specimens. These were published in Shanidar, The First Flower People (1971), a book that Solecki wrote for a general audience. His assertion that Neanderthals buried their dead was provocative because it indicated they were more like modern humans than many scientists thought at the time. Solecki’s interpretation of the Shanidar 4 “flower burial” remains the most controversial because he used it to argue that Neanderthals possessed behaviors and a mentality usually only attributed to later Cro-Magnon people (the humans who inhabited Europe during the end of the Ice Age). The discoveries at Shanidar did contribute to changing attitudes among paleoanthropologists about the Neanderthals during the later decades of the twentieth century.

Meanwhile Solecki’s career was advancing. He served as curator of archaeology at the Smithsonian Institution from 1958 to 1959. In 1959 he accepted a position as professor in the Anthropology Department at Columbia University, where he remained until 1988. Rose Solecki was also hired as a research associate in the Anthropology Department and worked closely with her husband throughout their careers. While at Columbia Solecki had opportunities to work at sites throughout the Middle East and Africa. He conducted excavations of prehistoric sites as part of the Columbia University Nubian Expedition in Sudan from 1961 to 1962. During the Columbia University expedition to Turkey in 1963, he discovered prehistoric cave paintings of animals. Ralph and Rose Solecki led a series of excavations of the Paleolithic deposits in the rock shelters at Yabroud (or Yabrud), in Syria, first from 1963 to 1965, then again in 1981 and from 1987 to 1988. The German archaeologist Alfred Rust first studied the site in the 1930s, and in fact Rust spent time with the Soleckis during their initial excavations at the site. In 1969, 1970, and 1973 Solecki excavated caves at Nahr Ibrahim, in Lebanon, where he unearthed Middle Paleolithic artifacts. Plans to return for another season in 1975 were derailed by the deteriorating political situation in the country. He also excavated the Middle Paleolithic site at El Masloukh in Lebanon in 1969.

Solecki organized an important conference held in 1969 at the Institute of Archaeology in London sponsored by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. The conference brought together experts on the Paleolithic archaeology of the Levant in order to formulate a common typology for Upper Paleolithic and Epi-Paleolithic artifacts, using objects from the site of Ksar Akil held in the Institute of Archaeology’s collections. Solecki was a member of several scientific organizations, including the Society for American Archaeology and the Anthropological Society of Washington. He served on the board of trustees of the American Schools of Oriental Research and was one of the founders in 1980 of the Professional Archaeologists of New York City, an organization established to protect and preserve archaeological and historic resources in New York City. During the early 1950s Solecki used aerial photography to identify and examine archaeological sites and later published a paper on the use of aerial photography and photo-interpretation in archaeology (Solecki 1957). Ralph and Rose Solecki both retired from Columbia University in 1988, but in 1990 they accepted positions as adjunct professors at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas. They continued to publish and to study the archaeological material they had collected over their long careers. The Soleckis collaborated with anthropologist Anagnostis Agelarakis to study the many artifacts and skeletons originally excavated from the Proto-Neolithic cemetery in Shanidar Cave. This resulted in the publication of The Proto-Neolithic Cemetery in Shanidar Cave in 2004, which not only examined the material recovered from the site but also discussed the mortuary customs of this population. In 2000, Ralph and Rose left Texas A&M University and moved to South Orange, New Jersey. Ralph Solecki died of pneumonia on 20 March 2019 in Livingston, New Jersey. In 2017, members of the Department of Anthropology Collections and National Anthropological Archives began the Ralph S. and Rose L. Solecki Papers and Artifacts Project to preserve their archaeological specimens and manuscript materials.

Selected Bibliography

“Archeology and Ecology of the Arctic Slope of Alaska.” Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution [1950] (1951): 469-495.

Exploration of an Adena Mound at Natrium, West Virginia. (Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 151). Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1953.

“Shanidar Cave: A Paleolithic Site in Northern Iraq.” Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution (1954): 389-425.

“Practical Aerial Photography for Archaeologists.” American Antiquity 22 (1957): 337-352.

“Three Adult Neanderthal Skeletons from Shanidar Cave, Northern Iraq.” Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution [1959] (1960): 603-635.

“New Anthropological Discoveries at Shanidar Northern Iraq.” Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences ser. 2, 23 (1961): 690-699.

Shanidar, The First Flower People. New York: Knopf, 1971.

Ralph Solecki, Rose Solecki and Anagnostis Agelarakis, The Proto-Neolithic Cemetery in Shanidar Cave. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004.

“Reminiscences of Plains Archaeology, Pre- and Post-World War II.” Plains Anthropologist 51(2006): 537-552.

Stanley Wisniewski and Ralph Solecki, The Archaeology of Maspeth, Long Island, New York and Vicinity. Rochester: New York State Archaeological Association, 2010.

Other Sources Cited

Muzaffer Şenyürek, “The Skeleton of the Fossil Infant Found in Shanidar Cave, Northern Iraq.” Anatolia 2 (1957): 49-55.

Muzaffer Şenyürek, “A Further Note on the Palaeolithic Shanidar Infant.” Anatolia 2 (1957): 111-121.

T. Dale Stewart, “First Views of the Restored Shanidar 1 Skull.” Sumer 14 (1958): 90-96.

T. Dale Stewart, “The Restored Shanidar 1 Skull.” Smithsonian Report for 1958 (1959): 473-480.

T. Dale Stewart, “Shanidar Skeletons IV and VI.” Sumer 19 (1963): 8-25.

T. Dale Stewart, “The Neanderthal Skeletal Remains from Shanidar Cave, Iraq: A Summary of Findings to Date.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 121 (1977): 121-165.

Erik Trinkaus, The Shanidar Neandertals. New York: Academic Press, 1983.

Secondary Sources

Sam Roberts, “Ralph Solecki, 101, Archaeologist Who Uncovered the Inner Life of Neanderthals.” The New York Times (April 17, 2019): Section B, p. 14.