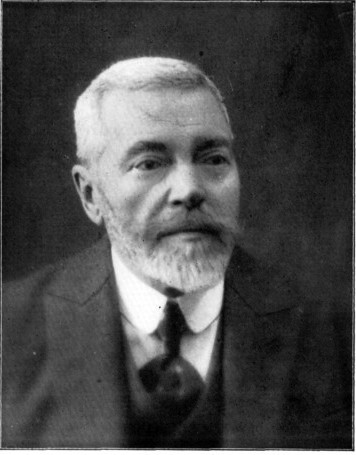

Henri Martin (Léon Henri-Martin) (1864–1936)

Matthew Goodrum

Henri Martin was born in Paris on 5 March 1864 into an illustrious family. His father Henri-Charles Martin was a physician, naturalist, and explorer who amassed a substantial entomological collection that he donated to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. His mother was Marie Joséphine Elisabeth Duseigneur, whose father was the sculptor Jean Bernard Duseigneur. Martin’s paternal grandfather, also named Henri Martin, was a famous historian who served as a Senator in the French government. He was also a member of several prominent institutions including the Société de Anthropologie de Paris, the Académie Française, and he served as president of the Commission des Monuments Mégalithiques. He was, moreover, a friend of Jacques Boucher de Perthes, whose excavations in the 1830s and 1840s provided some of the earliest archaeological evidence for the existence of humans during the Ice Age. Before proceeding further it will be helpful to address the change in Martin’s name. For most of his career, he was known as and published under the name Henri Martin, although he was often distinguished from his grandfather by the title of doctor Henri Martin. The French government authorized Martin to change his name to Léon Henri-Martin on 15 June 1931, yet there is evidence in some documents that he informally went by this name for many years prior to having it officially changed. Since current writers refer to him as Léon Henri-Martin, I will do so hereafter.

As a young boy Henri-Martin had an interest in the natural sciences, which led him to accompany his father on voyages to the Caucasus and to Algeria. During the meeting of the Association Française pour l’Avancement des Sciences (French Association for the Advancement of Science) in Algiers in 1881, Henri-Martin joined an excursion organized by his grandfather to see the megalithic monuments of Algeria located in the province of Constantine. Henri-Martin graduated with a degree in the natural sciences from the Sorbonne in 1888, and with the encouragement of his father, he then decided to study medicine. He entered the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Paris where he studied under the renowned professor of histology Mathias-Marie Duval. Henri-Martin served as an externe at the hospital of Paris and obtained his degree in medicine in 1894 with a thesis titled Recherches anatomiques et embryologiques sur les artères coronaires du cœur chez les vertébrés (Anatomical and Embryological Researches on the Coronary Arteries of the Heart among the Vertebrates), which earned a gold medal. On 5 January 1895, shortly after completing his medical degree, Henri-Martin married Lucie-Marie-Louise Huet. They had three children: Charlotte-Simone, Charlotte-Germaine, and Bernard.

As reflected in the topic of his medical thesis, Henri-Martin’s early scientific interest was in embryology and herpetology. He spent the period from 1899 to 1901 studying the organs relating to venom in vipers, which led to the publication of several papers on the subject. Henri-Martin’s life as a physician and researcher living in Paris was interrupted in December 1908 when he went to Messina as the head of the French delegation of the Red Cross, part of the international relief effort, after the great earthquake and tsunami that struck the Sicilian city. When the First World War began, Henri-Martin insisted on joining the war effort despite his age. He served as a volunteer doctor (Médecin-major of a regiment) and later became the assistant to the Médecin général attached to the Third Army. He was wounded twice during the war, first during the bombardment of Arras and later at Verdun. When doctors at the front noticed that apparently minor chest wounds often proved fatal as a result of complications, Henri-Martin was put in charge of an investigation into this phenomenon in 1916. As a result of his research, which involved performing autopsies of many soldiers, he learned the causes of these complications, and for this he was awarded the prix Monthyon [Monthyon Prize for Medicine and Surgery] by the Académie des Sciences in 1918, and the prix Godard (Godard Prize) by the Académie de Médecine in 1919.

In May 1916, the French government established a service called the Archives et Documents de la Guerre (Archives and Documents of the War) which led to the creation of a museum located at Val-de-Grâce in Paris (the Musée du service de santé des armées, colloquially called the Musée du Val-de-Grâce) that consisted of an anatomy and clinical collection, a historical museum, and a library. The archives and collections were designed to illustrate the work of the military health service during the Great War. Henri-Martin and several other doctors were responsible for the anatomical and clinical collection. During the war, he conducted thousands of autopsies of soldiers, which allowed him to assemble a unique collection displaying combat wounds in various organs of the human body. For years after the war, this collection at the museum was used to train military doctors at the Ecole d’Application du Service de Santé Militaire. As part of this work, Henri-Martin also published a respected work on the combat wounds in the lungs that received a grand prize from the Académie des Sciences. He also contributed to the Iconographie du Musée du Val-de-Grâce (Iconography of the Museum of Val-de-Grâce), composed under the direction of Octave Jacob, who was the Médecin militaire inspecteur during the war, which illustrated and described the wounds sustained by soldiers (Jacob 1918).

While Henri-Martin’s early scientific interests were in embryology and herpetology, by the turn of the new century, his interests turned to prehistoric archaeology. He was one of the founding members (along with Paul Reymond and Emile Rivière) of the Société Préhistorique de France when it was formally established in 1904 (it was renamed the Société Préhistorique Française in 1911). Henri-Martin attended the first Congress held by the Société Préhistorique de France in the French town of Périgueux in 1905, and this led to the events that would define the rest of his career. During the Congress, he visited the site of La Quina, located about thirty kilometers southeast of the town of Angoulême in the department of Charente. The site consists of a rockshelter and deposits lying at the foot of a cliff along the Voultron River. Archeologists had previously explored the site, but Henri-Martin recognized its potential significance, so he bought the land with the intention of undertaking new excavations. The French prehistoric archaeologist and geologist Gustave Chauvet first explored La Quina in 1872, and the construction of a road there in 1881, which exposed animal bones and artifacts, led Chauvet and others to conduct new excavations. Henri-Martin began new excavations at La Quina in 1905 and he continued working at the site until 1936. His numerous archaeological and paleontological discoveries and his many publications based on his years of research at La Quina made important contributions to Paleolithic archaeology and paleoanthropology.

Henri-Martin still had his medical practice in Paris, but between 1905 and the outbreak of war in 1914, he devoted his vacations to exploring the deposits at La Quina. He conducted meticulous excavations, digging a trench that exposed the stratigraphy of the site. He unearthed Mousterian and Aurignacian occupation levels that contained abundant stone and bone tools as well as numerous animal bones. The animal fossils in the Mousterian level were mostly reindeer and horse with some mammoth, cave hyena, bison, and other animals. The vast collection of artifacts found at the site over the years allowed Henri-Martin to trace the development of bone and stone tools during the Mousterian at La Quina. He undertook innovative studies of bone artifacts (made from the humerus and foot bones from horse, reindeer, and bison) that were used to retouch flint tools, which shed light on how some Mousterian tools were made. While identifying and classifying the various types of artifacts found at La Quina, Henri-Martin described intensively retouched stone tools from the site that he called Moustérienne perfectionée (perfected Mousterian). He also traced the development of Mousterian artifacts, which displayed greater complexity over time, thus demonstrating the improvement of Neanderthal tool-making abilities throughout the Mousterian. Henri-Martin did most of the excavating at La Quina himself, although over the years, he was assisted by several people including Louis Giraux, who was one of the founding members of the Société Préhistorique de France. Giraux collaborated with Henri-Martin in studying the bone tools and the evidence of butchery found on animal bones at the site. In fact, Henri-Martin pioneered the study of the marks that stone tools leave on animal bones.

The results of these early studies of the Mousterian artifacts and animal bones at La Quina led to a series of monographs that appeared sequentially over many years. Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, Charente. Ossements utilisés (Researches on the Evolution of the Mousterian in the Deposits of La Quina, Charente), published in two sections in 1907 and 1909, discussed the use of bone tools during the Mousterian and presented a stratigraphy of the site. This was followed by a third installment on bone tools published in 1910, which along with the previous two sections form the first volume of Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, Charente. Volume two, titled Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, (Charente). Industrie lithique, was published in 1923. In addition to describing the stone tools from La Quina and presenting a typology of stone tool types, the monograph reflects Henri-Martin’s interest in examining how Mousterian people used stone tools.

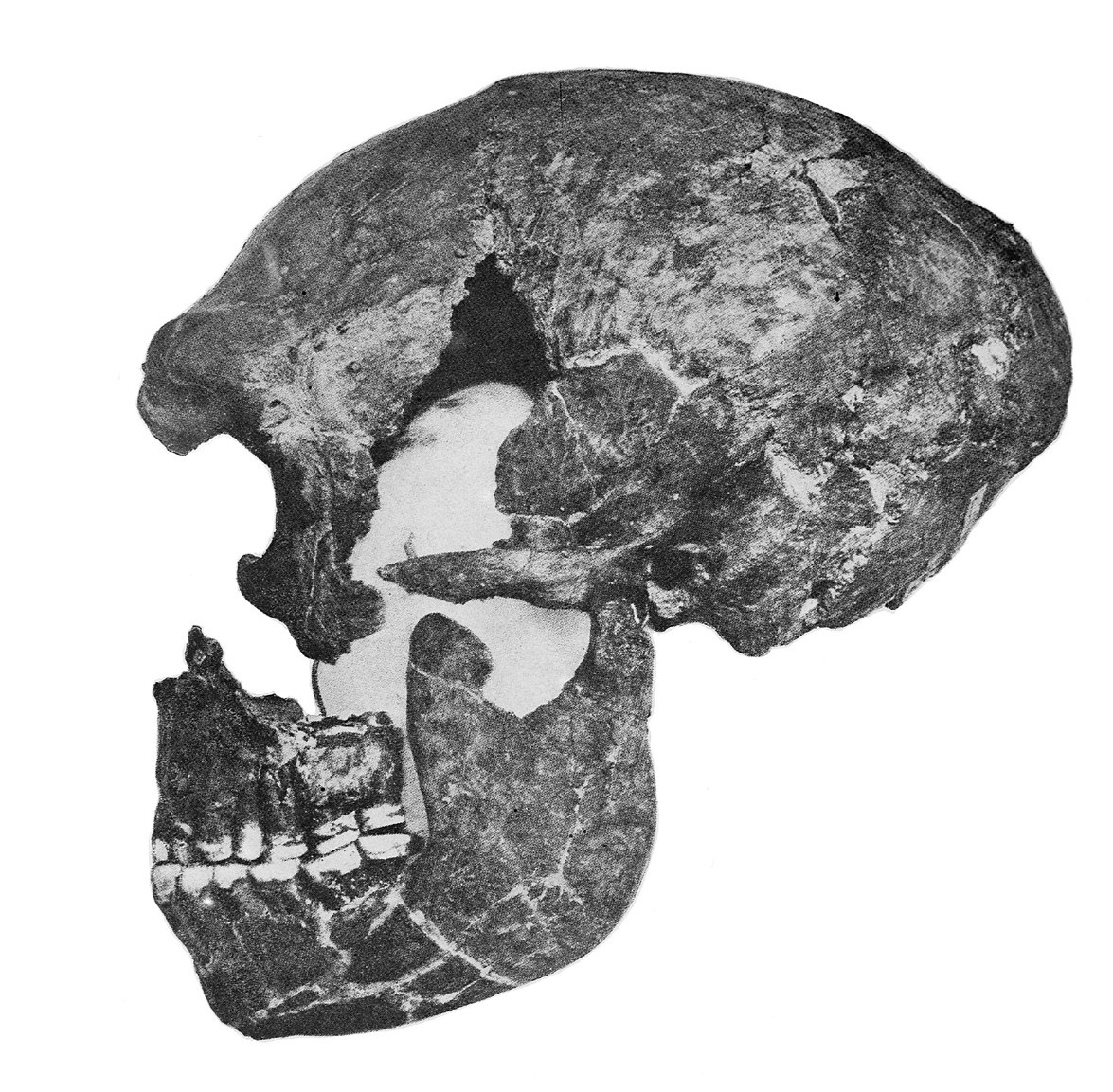

In addition to stone and bone tools, Henri-Martin also began to find isolated fragments of fossilized human bones. Then on 18 September 1911, Henri-Martin unearthed a skeleton of a female Neanderthal lying at the base of the Mousterian layer. His first announcement of the discovery was at the Académie des Sciences on 16 October 1911 (Henri-Martin 1911a), which was followed by a paper read on 26 October at the Société Préhistorique Française (Henri-Martin 1911b). During the 1912 meeting of the Congrès Préhistorique de France held in the nearby town of Angoulême, Henri-Martin guided the attendees through the site, so they could inspect the deposit where the Neanderthal skeleton was found. Neanderthal skeletons were rare and there was still a great deal that was uncertain about their anatomy and their place in human evolution. A nearly compete Neanderthal skeleton discovered in August 1908 in a cave near the French village of La Chapelle-aux-Saints had been taken to the Museum of Natural History in Paris where the paleontologist Marcellin Boule conducted the most thorough examination to date of any Neanderthal remains (Boule 1911, 1912, 1913). Boule’s conclusions were very influential, and they elevated the La Chapelle-aux-Saints skeleton to considerable prominence, but it was not the only Neanderthal skeleton recently discovered. Otto Hauser, a Swiss amateur archaeologist, unearthed a nearly complete Neanderthal skeleton from the French site of Le Moustier in March 1908, which was examined by the German anthropologist Hermann Klaatsch. And during 1909 and 1910, the French anthropologist Louis Capitan and his collaborator Denis Peyrony discovered first a male Neanderthal skeleton then a female Neanderthal skeleton at La Ferrassie in the Vézère valley. Thus, the La Quina Neanderthal skeleton was one in a series of important Neanderthal specimens discovered in the span of just four years.

Henri-Martin, who was trained as an anatomist, extracted the bones from the matrix and performed an examination of the skeleton. He determined it belonged to a female and estimated that she had been less than thirty years old when she died. Despite the evidence that the La Chapelle-aux-Saints and the La Ferrassie Neanderthal specimens had been intentionally buried, the lack of disturbed sediment around the La Quina skeleton led Henri-Martin to think this was not a burial. However, a number of scientists, including the American physical anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička, questioned this conclusion. Hrdlička thought Neanderthals would not abandon their dead. Henri-Martin published several papers on his analysis of the skull from La Quina, along with a photograph of his reconstruction of the skull (Henri-Martin 1911b, 1911e, 1912a, 1912d, 1913a). His reconstruction of the skull was likely influenced by Marcellin Boule’s conception of the Neanderthals and their place in human evolution, which resulted in a more simian appearance to the skull than some anthropologists were willing to agree with. Henri-Martin also published a series of papers between 1911 and 1913 containing detailed and thorough descriptions of the La Quina skeleton.

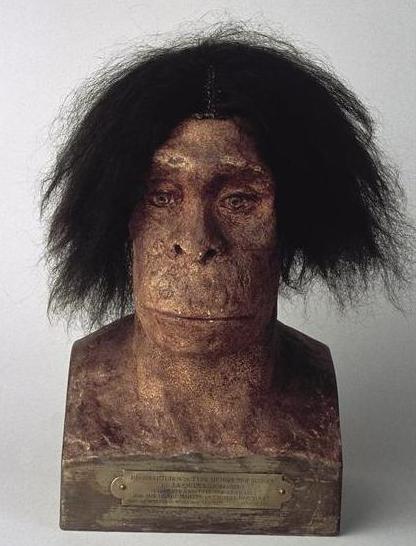

Aleš Hrdlička traveled to La Quina to visit Henri-Martin in 1912 and inspected the specimen. This allowed him to provide a lengthy description of the site and the skeleton in the Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution (Hrdlička 1913). Besides the scientific descriptions of the La Quina skeleton, Henri-Martin also collaborated with the sculptor Charles Bousquet in 1913 to produce a bust representing their image of what this Neanderthal would have looked like when alive (this bust is currently held in the collections at the Musée d’Archéologie Nationale in Paris). However, while Henri-Martin agreed with Boule on the apelike nature of the Neanderthals, he disagreed with him on their cultural attainments, rejecting the notion that they were brutish by noting their tools, hunting, and butchering abilities. Henri-Martin began work on a major monograph on the skeleton (Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, (Charente). Vol. III, L’Homme fossile de La Quina), but this work was delayed by World War I and only appeared in 1923 and focused mostly on the skull (Henri-Martin 1923a).

As work at La Quina progressed and Henri-Martin accumulated a growing collection of artifacts and animal fossils, it became necessary to create a laboratory at the site. He bought a beautiful old structure known as the Logis du Peyrat, located near the village of Blanzaguet-Saint-Cybard. He transformed it into a country house and constructed a Laboratoire d’Études de Paléontologie Humaine to house his collection and provide workspace for his investigations. The laboratory was devoted to the study of prehistory and comparative anatomy and eventually became associated with the École Pratique des Hautes Études in 1925. As a growing number of scientists began to visit La Quina, Henri-Martin welcomed them to stay at the country house and inspect the collections at the laboratory. Among those visitors was Charles Peabody, director of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University, who visited La Quina during the meeting of the Congrès Préhistorique de France in 1912. The two men developed a close relationship and Henri-Martin decided to donate some archaeological specimens to the Peabody Museum. Peabody returned to La Quina in late September 1913 when he spent ten days assisting Henri-Martin with some excavations and he conducted a study of the stone tools from the site (Peabody 1914).

Henri-Martin acquired a reputation as an indefatigable researcher who was friendly and welcoming to fellow scientists that frequently visited La Quina to inspect the collections housed in the Laboratory or to participate in excavations. Henri-Martin was also active in many prominent scientific institutions in France. As mentioned earlier, he was one of the founding members of the Société Préhistorique Française, and in 1910 he was named its honorary president. He remained active in the Society throughout his life, and he served as president of the 1912 meeting of the Congrès Préhistorique de France, which was held in Angoulême. Henri-Martin became a member of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (Anthropology Society of Paris) in 1914, and he was a member of the Société Archéologique et Historique de la Charente (Archaeological and Historical Society of Charente). Henri-Martin became a member of the Institut Français d’Anthropologie (French Institute of Anthropology), which had been created in 1911, and served as its president from 1930 to 1933. He was also one of the original members of the Société des Africanistes (Society of Africanists), which was founded in 1930 to promote anthropological, sociological, linguistic, economic, archaeological, and geographical research about Africa in France.

Henri-Martin also played a role in facilitating prehistoric research by American scientists. It was Henri-Martin, through his collaborations with the American archaeologist Charles Peabody, who first suggested the establishment of the American School of Prehistoric Research. The school, which was initially called the American Foundation in France for Prehistoric Studies or alternatively the American School in France of Prehistoric Studies), was founded in 1921 through the efforts of Charles Peabody and George Grant MacCurdy, professor of anthropology at Yale University. It was created to give American students an opportunity to participate in excavations in France and to visit the country’s museum collections. Henri-Martin generously invited the School to conduct excavations at La Quina and MacCurdy led the first season in 1921, Peabody led the second season in 1922, and Aleš Hrdlička led the third season in 1923, but these excavations produced few artifacts.

Henri-Martin’s decades of excavations at La Quina not only produced a substantial collection of archaeological artifacts and human fossils. It also allowed him to present a much more complete picture of the development of Mousterian, and even Aurignacian artifacts, than existed previously. He also developed pioneering works on taphonomy and experimental archaeology, and he developed groundbreaking techniques for studying Paleolithic artifacts. He conducted detailed examinations of the Neanderthal fossils from La Quina and the Homo sapiens fossils from Roc-de-Sers and published careful descriptions of these finds. This important work, however, has been overshadowed by Marcellin Boule’s research on the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neanderthal. Today it seems that Henri-Martin’s archaeological research is more recognized and cited than his anatomical descriptions of the human skeletal remains. Henri-Martin donated large portions of his extensive collection of archaeological and paleontological artifacts to several museums including the Musée des Antiquités Nationales, the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, the Muséum de Toulouse, the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de Lyon, and numerous other institutions in France and abroad. A hall containing objects Henri-Martin had collected was named for him at the Musée des Antiquités Nationales. Despite receiving little financial support during the early period of his research, Henri-Martin was later praised for not selling his valuable artifacts as some archaeologists had.

He received several honors in the course of his life. He was named an Officer of the Légion d’Honneur in recognition of his service during World War I. Toward the end of his career, he was given the title of director of the École Pratique des Hautes Études in recognition of his many years of work. Henri-Martin continued to work at La Quina until his death at his country house at La Peyrat, in Blanzaguet-Saint-Cybard, on 9 June 1936. He was buried at the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. His daughter Germaine Henri-Martin continued the excavations at La Quina and took over the Laboratory at La Peyrat. In 1976 she donated the remaining collection held at the Laboratory to the Musée des Antiquités Nationales.

Selected Bibliography

Henri Martin and Charles Ovion, “Contribution à l’étude de la cité lacustre de Condette (Pas-de-Calais).” Compte-Rendu de la Congrès préhistorique de France [1905] (1906): 433-442.

Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, Charente. Fascicule 1, Ossements utilisés. Paris: C. Reinwald: Schleicher frères, 1907.

Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina (Charente). Fascicule 2, Ossements utilisés. Paris: C. Reinwald: Schleicher frères, 1909.

Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, (Charente). Fascicule 3, Industrie osseuse. Paris: C. Reinwald: Schleicher frères, 1910.

“Sur un squelette humain de l’époque moustérienne trouvé en Charente.” Compte-Rendu de l’Académie des Sciences 153 (1911a): 728-729.

“Présentation d’un crâne humain trouvé avec le squelette à la base du moustérien de La Quina (Charente).” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 8 (1911b): 615-627.

“Découverte d’un squelette humain de l’époque moustérienne inférieure de la Quina (Charente).” L’Homme préhistorique (1911c): 225-232.

“Dents humaines moustériennes de La Quina (Charente).” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 8 (1911d): 247.

“Présentation de moulages et de photographies. Reconstitution du crâne de l’homme fossile de La Quina.” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 8 (1911e): 740-741.

“L’homme fossile moustérien de la Quina; reconstitution du crâne.” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 9 (1912a): 389-424.

“Position stratigraphique des ossements humains recueillis dans le Moustérien de La Quina de 1908 à 1912.” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 9 (1912b): 700-709.

“L’homme fossile de La Quina.” L’Homme préhistorique (1912c): 225-227.

“Le crâne de l’homme fossile moustérien de La Quina.” Compte-Rendu de l’Association Française pour l’Avancement des Sciences (1912d): 538-539.

“Répartition des ossements humains trouvés dans le gisement moustérien de La Quina (Charente).” Compte-Rendu de l’Académie des Sciences 155 (1912e): 982-983.

“À propos de la découverte de l’homme fossile de la Quina.” Revue des études anciennes (1912g): 61-64.

“Reconstitution du type néanderthalien sur le crâne de l’homme fossile de La Quina ” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 10 (1913a): 86-88.

“Nouvelle série de débris humains disséminés, trouvés en 1913, dans le gisement moustérien de La Quina.” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 10 (1913b): 540-543.

“Présentation d’un crâne d’enfant âgé de huit ans, trouvé en place dans le Moustérien supérieur du gisement de La Quina.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie 1 (1920): 113-125.

“Un crâne d’enfant néandertalien provenant du gisement de La Quina (Charente).” L’Anthropologie 31 (1921a): 331-334.

“Sur la répartition des ossements humains dans le gisement de La Quina.” Charente, L’Anthropologie 31 (1921b): 340-345.

“Etude d’une rotule humaine trouvée dans le Moustérien de la Quina (Charente).” Compte-Rendu de l’Association Française pour l’Avancement des Sciences (1921c): 955-958.

Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, (Charente). Vol. II. Industrie lithique. Angoulème: Imprimerie ouvriere, 1923a.

Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, (Charente). Vol. III, L’Homme fossile de La Quina. Paris: O. Doin, 1923b.

“Un squelette humain d’âge indéterminé, inhumé dans le Moustérien supérieur de La Quina.” L’Anthropologie 33 (1923c): 188.

“Un crâne trouvé en Charente (vallée du Roc).” L’Anthropologie 34 (1924): 298-301.

“La station aurignacienne de la Quina,” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris ser. 7, 6 (1925): 10-17.

Recherches sur l’évolution du Moustérien dans le gisement de La Quina, (Charente). Vol. IV. L’enfant fossile de La Quina. Angoulème: Imprimerie ouvriere, 1926.

“Mâchoire humaine moustérienne trouvée dans la station de La Quina.” L’homme préhistorique 13 (1926d): 3-21.

“Caractères des squelettes humains quaternaires de la vallée du roc (Charente).” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris ser. 7, 8 (1927): 103-129.

La Frise sculptée et l’atelier Solutréen du Roc (Charente). (Archives de l’Institut de Paléontologie humaine, Mémoire 5). Paris: Masson et Cie, 1928a.

Études sur le Solutréen de la vallée du Roc (Charente). Angoulême: Imprimerie Ouvrière, 1928b.

“Le crâne d’enfant néanderthalien de La Quina.” Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société archéologique et historique de Charente [1926-27] (1928c): xcvi-ciii.

“Les sculptures du Roc.” Préhistoire 1 (1932): 1-8.

Other Sources Cited

Marcellin Boule, “L’Homme fossile de la Chapelle–aux–Saints.” Annales de Paléontologie 6 (1911): 109-172.

Marcellin Boule, “L’Homme fossile de la Chapelle–aux–Saints.” Annales de Paléontologie 7 (1912): 105-192.

Marcellin Boule, “L’Homme fossile de la Chapelle–aux–Saints.” Annales de Paléontologie 8 (1913): 209-278.

Aleš Hrdlička, “The Most Ancient Skeletal Remains of Man.” Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (1913): 491-552 (on La Quina see pp. 544-46).

Octave Jacob, Iconographie du Musée du Val-de-Grâce. (With the collaboration of Doctors Lannou, Latarjet, Lefort, Henri-Martin, Pascal, Perret, de Rothschild). Paris: Aristide Quillet, 1918.

Charles Peabody, “Ten Days with Dr. Henri Martin at La Quina.” American Anthropologist n.s. 16 (1914): 257-67.

Secondary Sources

Henri Vallois. “Le docteur Henri Martin.” Les Cahiers de Marottes et Violons d’Ingres n. s. 47 (1959): 7-20.

A. Vayson de Pradenne (Société Préhistorique Française), R. Lantier (Musée des Antiquités Nationales), Etienne Rabaud (Institut Français d’Anthropologie), and L. Joleaud (Sorbonne), “Nécrologie: Docteur Henri-Martin.” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 33 (1936): 354-363.

R. L. “Le Dr. Léon Henri-Martin (1864-1936).” Revue archéologique ser. 6, 8 (1936): 92-94.

Léonce Joleaud, “Mort du Docteur Léon Henri-Martin.” Journal des Africanistes 6 (1936): 231-232.

Etienne Patte, “L’œuvre scientifique du Docteur Henri-Martin.” Mémoires de la Société Archéologique et Historique de la Charente (Supplement) (1965): 79-89.

“Henri-Martin (Léon-Henri).” In François Julien-Labruyère and Robert Allary (eds.), Dictionnaire biographique des charentais et de ceux qui ont illustré les Charentes. Pp. 676-677. Paris: Croît vif, 2005.