Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger (1856-1936)

Matthew Goodrum

Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger was born in Zagreb on 25 October 1856 in what at the time was the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father, Matija Kramberger, (who descended from Germans that immigrated to the region in 1648) worked as a cobbler and innkeeper, and his mother, Terezija Duŝek (née Vrbanović) was Croatian. They christened their son Karl Kramberger, but in 1882 he adopted the Croatian version of his name due to his growing dedication to Croatian nationalism. As a boy, he began collecting fossils from a nearby quarry at Dolje after being introduced to natural history by a local pharmacist and taxidermist Slavoljub Wormastiny, who worked at the National Museum in Zagreb. This led Gorjanović-Kramberger to study geology and paleontology, first at the University of Zurich in 1874 and later at the University of Munich where he studied under the renowned paleontologist Karl Alfred von Zittel. However, Gorjanović-Kramberger transferred once again and completed his doctorate in the natural sciences at the University of Tübingen in 1879 with a dissertation on fossil fish from the Carpathian Basin.

Gorjanović-Kramberger became curator of the Mineralogy and Geology Department at the Croatian National Museum in Zagreb in 1880, where he later served as director of the Department of Geology and Paleontology from 1893 to 1924. In 1884 he also accepted a position as assistant professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Zagreb, becoming full professor in 1896. He was also active in several local scientific institutions. Gorjanović-Kramberger was part of the group led by Spiridion Brusina, professor of zoology at the University of Zagreb, that established the Hrvatskoga naravoslovnoga družtva (Croatian Natural History Society) in Zagreb in 1885. The Society, which changed its name to Hrvatsko Prirodoslovno Društvo (Croatian Society for Natural Sciences) in 1908, was created to promote interest and research in the natural sciences in Croatia. He was made an associate member of the Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti (Yugoslav Academy of Arts and Sciences) in 1892, becoming a full member in 1909. The Academy had been established in Zagreb in 1866 by Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer as part of a broader cultural and intellectual project to unite the Slavic peoples of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

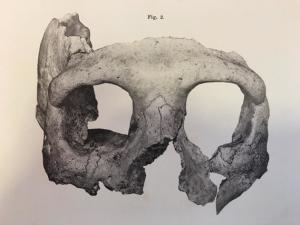

Gorjanović-Kramberger was engaged in a wide range of projects including cartography and the geological surveying of Croatia as well as the study of fossil Miocene fish and Cretaceous lizards. His career took a dramatic turn when he first learned of a rock shelter at Hušnjak Hill, located on the outskirts of the town of Krapina along the Krapinica River. Sand had been quarried from the site for years and Gorjanović-Kramberger first learned of the site when a local schoolteacher named Josip Rehorić sent some recently discovered Pleistocene animal fossils to him in 1895. Gorjanović-Kramberger visited Hušnjak Hill on 23 August 1899 and immediately noticed remains of hearths, stone tools, and a human molar in the cave’s deposits. He began excavations at Krapina on 2 September 1899 with the assistance of Stjepan Osterman, a student at the University of Zagreb. Between 1899 and 1905, Gorjanović-Kramberger unearthed about nine hundred hominid fossils from more than seventy individuals and over a thousand stone implements, as well as vast quantities of Pleistocene animal fossils.

The excavations were meticulously conducted and recorded, the stratigraphy of the site was mapped, each fossil was numbered, and the position of every fossil was recorded. Gorjanović-Kramberger also introduced several innovative techniques in his research. He photographed fossils and used these in his publications, and he was one of the first paleontologists to use the new X-ray technology to produce a radiograph of a fossil. He also experimented with the use of fluorine dating to prove that the hominid fossils and the Pleistocene mammals were of the same age. When he first began the excavations at Krapina, he dated the animal and human remains to the diluvial period, the term generally used to refer to the glacial period (Pleistocene), but as geologists refined the chronology of the Pleistocene, Gorjanović-Kramberger eventually dated the fossils to the Riss-Würm interglacial period. Gorjanović-Kramberger was influenced in his interpretation of the Krapina hominid fossils by comparing them with the Neanderthal jaw discovered in 1866 at La Naulette, in Belgium, and with the Neanderthal jaw excavated from the Ŝipka cave, in Moravia, in 1880. His views were also shaped by discussions he had with German anatomist Gustav Schwalbe at the 1903 meeting of the Gesellschaft Deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte, held in Kassel, Germany. Schwalbe promoted the view that the Neanderthals, or Homo primigenius as he called them, were the ancestors of modern humans. As a result of these influences, Gorjanović-Kramberger identified the Krapina fossils as belonging to Homo primigenius (Neanderthal), and he also recognized that the stone implements discovered at Krapina resembled Mousterian implements found at other sites in Europe.

Gorjanović-Kramberger first announced his discoveries at Krapina in a paper read during the 16 December 1899 meeting of the Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti (Yugoslav Academy of Arts and Sciences) in Zagreb. He followed this with a paper read on 19 December at the Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien (Anthropological Society of Vienna). Between 1899 and his death, Gorjanović-Kramberger published a substantial number of papers, mostly in German, on the Krapina fossils. His monograph on the Krapina fossils, Der diluviale Mensch von Krapina in Kroatien [Diluvial Man from Krapina in Croatia] published in 1906, discussed the geology and animal fossils found at the site and described in great detail the morphology of the Neanderthal material. One of Gorjanović-Kramberger’s major contributions to the interpretation of the Neanderthals was his recognition that the population represented in the Krapina sample showed considerable morphological variation. He explained the anatomical traits that distinguished the Neanderthals from modern humans, notably their large and robust bones, as being the result of the harsh climate they had to endure and to their possessing only rudimentary tools. He also identified many examples of injuries in the fossils from Krapina, which he interpreted as evidence that life for these people was also full of dangers. He even suggested that the Neanderthals of Krapina engaged in cannibalism since some of the bones were charred and had been broken. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Gorjanović-Kramberger believed that the Neanderthals were the direct ancestors of modern humans and he also supported the Darwinian idea that humans had evolved originally from an ape-like ancestor through stages represented by specimens such as Pithecanthropus erectus (now Homo erectus).

Although Gorjanović-Kramberger published extensively on the Krapina Neanderthals and delivered lectures in many major German and East European cities, he did not visit France, England, or America, and as a result, his research was not well known outside the German speaking parts of Europe, although the American physical anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička did discuss the Krapina Neanderthals in The Skeletal Remains of Early Man (1930). It was not until the work conducted by Fred H. Smith and Milford Wolpoff during the 1970s that paleoanthropologists began to take a renewed interest in the Krapina material. In addition to his excavations at Krapina, Gorjanović-Kramberger was also instrumental in the formation of the Geologijsko povjerenstvo za kraljevinu Hrvatsku i Slavoniju [Geological Commission of the Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia] in 1909, and he founded the journal Vijesti geoloskog povjerenstva [Geological Commission News] in 1911 and served as its editor. Gorjanović-Kramberger retired as professor at the University of Zagreb and from his position as director of the National Museum in 1924. He died in Zagreb on 22 December 1936.

Selected Bibliography

“Paleolitički ostaci čovjeka i njegovih suvremenika iz diluvija u Krapini.” Ljetopis Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 14 (1899): 90-98.

“Der paläolithische Mensch und seine Zeitgenossen aus dem Diluvium von Krapina in Croatien.” Mittheilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 29 (1899): 65–68.

“Neue paläolithische Fundstelle.” Correspondenz-Blatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 31 (1900): 17–18.

“Der diluviale Mensch aus Krapina in Kroatien.” Mittheilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 30 (1900): 203.

“Der paläolithische Mensch und seine Zeitgnossen aus dem Diluvium von Krapina in Kroatien.” Mittheilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 31 (1901): 164-197.

“Der paläolithische Mensch und seine Zeitgenossen aus dem Diluvium von Krapina in Kroatien (Nachtrag, als zweiter Theil).” Mittheilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 32 (1901): 189-216.

“Der paläolithische Mensch und seine Zeitgnossen aus dem Diluvium von Krapina in Kroatien. Zweiter Nachtrag (als dritter Teil).” Mittheilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 34 (1904): 187-199.

“Homo primigenius aus dem Diluvium von Krapina in Kroatien und dessen Industrie. (Nach den Ausgrabungen im Sommer des Jahres 1905.)” Correspondenz-Blatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 36 (1905): 88-90.

“Der paläolithische Mensch und seine Zeitgnossen aus dem Diluvium von Krapina in Kroatien. Dritter Nachtrag (als vierter Teil).” Mittheilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 35 (1905): 197-229.

Der Diluviale Mensch von Krapina in Kroatien: ein Beitrag zur Paläoanthropologie. Wiesbaden: Kneidel, 1906.

“Die Kronen und Wurzeln der Mahlzähne des Homo primigenius und ihre genetische Bedeutung.” Anatomische Anzeiger 31 (1907): 97–134.

“Die Zähne des Homo primigenius von Krapina.” Anatomische Anzeiger 32 (1908): 145–156.

“Anomalien und krank- hafte Erscheinungen am Skelett des Urmenschen von Krapina.” Die Umschau 12 (1908): 623–662.

“Anomalien und pathologische Erscheinungen am Skelett des Urmenschen von Krapina.” Correspondenz-Blatt der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 38 (1908): 108–112.

“Der vordere Unterkiefer- abschnitt des altdiluvialen Menschen in seinen genetischen Bezie- hungen zum Unterkiefer des rezenten Menschen und jenem der Anthropoiden.” Zeitschrift für induktive Abstammungs- und Vererbungslehre 1 (1909): 403–439.

“Der Urmensch von Krapina – Kannibale.” Anzeiger der 4. Versammlung der tschechischen Naturforscher und Ärzte (Prague) (1909): 288–299.

“Die verwandschaftlichen Beziehungen zwischen dem Homo heidelbergensis aus Mauer und dem Homo primigenius aus Krapina in Kroatien.” Anatomischer Anzeiger 35 (1910): 359–364.

“Über Homo aurignacensis Hauseri.” Verhandlungen der Geologischen Reichsanstalt 14 (1910): 300–303.

“Homo aurignacensis Hauseri in Krapina?” Verhandlungen der Geologischen Reichsanstalt 14 (1910): 312–317.

“Bemerkungen zu Walkhoffs neuen Untersuchunger über die menschliche Kinnbildung.” Glasnik Hrvatskoga prirodoslovnoga društva 24 (1912): 110–117.

“Der Axillarand des Schul- terblattes des Menschen von Krapina.” Glasnik Hrvatskoga prirodoslovnoga društva 26 (1914): 231–257.

“Der diluviale Mensch von Krapina.” Archiv für Rassenbilder 12 (1926): 111-120.

“Das Schulterblatt des diluvialen Menschen von Krapina in seinem Verhältnis zu dem Schulterblatt des rezenten Menschen und der Affen.” Vijesti geološk zavoda 1 (1926): 67-122.

“Die Halswirbel des diluvialen Menschen von Krapina.” Izvješća o raspravama matematičko-prirodoslovnog razreda 23 (1929): 24-48.

Secondary Sources

Ljudevit Barić. “Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger i otkriće krapinskog pračovjeka.” In Mirko Malez (ed.). Krapinski pračovjek i evolucija hominida. Pp. 23–51. Zagreb: Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1978.

Ljudevit Barić. “Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger and his Discovery of the Krapina Nanderthal Man.” Collegium Antropologicum 3 (1979): 125-128.

David Frayer, “The Krapina Neandertals: A Comprehensive, Centennial, Illustrated Bibliography.” Zagreb: Croatian Natural History Museum, 2006.

David Frayer, ““Gorjanović-Kramberger, Dragutin (Karl).” In New Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 3, pp. 154-157. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2008.

Milan Herak, “Znanstveno djelo Dragutina Gorjanović-Krambergera.” Geološki vjesnik 10 (1957): 1-7.

Vanda Kochansky-Devide, “Prof. dr. Gorjanović kao paleontolog.” In Mirko Malez (ed.). Krapina 1899-1969. Pp. 5–11. Zagreb: Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1970.

Vanda Kochansky-Devidé, “Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger kao antropolog. Krapinski pračovjek i evolucija hominida.” In Mirko Malez (ed.). Krapinski pračovjek i evolucija hominida. Pp. 53–59. Zagreb: Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1978.

Vanda Kochansky-Devide, “Prilozi povijesti geoloških znanosti, IV. Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger.” Geološki vjesnik 30 (1978): 427–442.

Vanda Kochansky-Devide, “Rad D. Gorjanovića-Krambergera na paleontologiji invertebrate.” In Mirko Malez (ed.). Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger: 1856-1936. Pp. 29-35. Zagreb: Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1987.

Mirko Malez, 1987 “Doprinos Dragutina Gorjanovića-Krambergera u geologiji kvartara, paleontologiji sisavaca i paleoantropologiji.” In Mirko Malez (ed.). Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger: 1856-1936. Pp. 51-75. Zagreb: Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1987.

Mirko Malez, “Dragutin Gorjanovi}-Kramberger (1856-1936) and His Contribution to the Advancement of Paleoanthropology and the Beginning of the 20th Century.” Collegium Antropologicum 12 (1988): 175–188.

Josip Poljak. “Dr. Gorjanović-Kramberger (Nekrolog).” Priroda 27 (1937): 1-4.

Josip Poljak, “Prof. Gorjanović-Kramberger kao paleontolog i geolog.” Spomenica u počast gospodinu profesoru Dru. Dragutinu Gorjanović-Krambergeru. Glasnik Hrvatskoga prirodoslovnoga društva 37/38 (1925/1926): 27-38.

Jakov Radovčić, Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger i krapinski pračovjek: Počeci suvremene paleoantropologije—Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger and Krapina Early Man: the Foundations of Modern Paleoanthropology. Zagreb: Hrvatski prirodoslovni muzej and Školska knjiga, 1988.

Marijan Salopek, “Dr. Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger.” Ljetopis Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 50 (1938): 188-192.

Marijan Salopek, “Akademik Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger kao paleontolog, geolog i paleoantropolog. “Rasprave i građa za povijest nauka. Institut za povijest prirodnih, matematičkih i medicinskih nauka, Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, Svezak 3 (1969): 153–171.

Antun Šimunić, “Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger Geological Mapping Pioneer in Croatia.” Kartografija i geoinformacije: casopis Hrvatskoga kartografskog društva 7 (2007): 52-72.

Fred H. Smith, “Gorjanović-Kramberger, Dragutin (Karl) (1856-1936).” In Frank Spencer (ed.), History of Physical Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 1, pp. 441-444. New York: Garland, 1997.

Winfried Henke, “Gorjanović-Kramberger’s Research on Krapina – Its Impact on Paleoanthropology in Germany.” Periodicum biologorum 108 (2006): 239-252.

Boris Zarnik, “Profesor Gorjanović-Kramberger kao antropolog.” Spomenica u počast gospodinu profesoru Dru. Dragutinu Gorjanović-Krambergeru. Glasnik Hrvatskoga prirodoslovnoga društva 37/38 (1925/1926): 39-48.