Chapter 5 Business in a Global Environment

Learning Objectives

- Explain why nations and companies participate in international trade.

- Describe the concepts of absolute and comparative advantage.

- Explain how trade between nations is measured.

- Define importing and exporting.

- Explain how companies enter the international market through licensing agreements or franchises.

- Describe how companies reduce costs through contract manufacturing and outsourcing.

- Explain the purpose of international strategic alliances and joint ventures.

- Understand how US companies expand their businesses through foreign direct investments and international subsidiaries.

- Appreciate how cultural, economic, legal, and political differences between countries create challenges to successful business dealings.

- Describe the ways in which governments and international bodies promote and regulate global trade.

- Discuss the various initiatives designed to reduce international trade barriers and promote free trade.

Do you wear Nike shoes or Timberland boots? Buy groceries at Giant Stores or Stop & Shop? Listen to Halsey, Billie Eilish, or Drake on Spotify? If you answered yes to any of these questions, you’re a global business customer. Both Nike and Timberland manufacture most of their products overseas. The Dutch firm Royal Ahold owns all three supermarket chains. And Spotify is a Swedish enterprise.

Take an imaginary walk down Orchard Road, the most fashionable shopping area in Singapore. You’ll pass department stores such as Tokyo-based Takashimaya and London’s very British Marks & Spencer, both filled with such well-known international labels as Ralph Lauren Polo, Burberry, and Chanel. If you need a break, you can also stop for a latte at Seattle-based Starbucks.

When you’re in the Chinese capital of Beijing, don’t miss Tiananmen Square. Parked in front of the Great Hall of the People, the seat of Chinese government, are fleets of black Buicks, cars made by General Motors in Flint, Michigan. If you’re adventurous enough to find yourself in Faisalabad, a medium-size city in Pakistan, you’ll see Hamdard University, located in a refurbished hotel. Step inside its computer labs, and the sensation of being in a faraway place will likely disappear: on the computer screens, you’ll recognize the familiar Microsoft flag—the same one emblazoned on screens in Microsoft’s hometown of Seattle and just about everywhere else on the planet.

The Globalization of Business

The globalization of business is bound to affect you. Not only will you buy products manufactured overseas, but it’s highly likely that you’ll meet and work with individuals from various countries and cultures as customers, suppliers, colleagues, employees, or employers. The bottom line is that the globalization of world commerce has an impact on all of us. Therefore, it makes sense to learn more about how globalization works. Although globalization has been the trend towards increased connections and interdependence in the world’s economies, there has been talk about nationalism from the impact of COVID-19 and trade agreements. However, this has yet to be determined, therefore, this chapter will focus on globalization as defined above.

Never before has business spanned the globe the way it does today. But why is international business important? Why do companies and nations engage in international trade? What strategies do they employ in the global marketplace? How do governments and international agencies promote and regulate international trade? These questions and others will be addressed in this chapter. Let’s start by looking at the more specific reasons why companies and nations engage in international trade.

Why Do Nations Trade?

Why does the United States import automobiles, steel, digital phones, and apparel from other countries? Why don’t we just make them ourselves? Why do other countries buy wheat, chemicals, machinery, and consulting services from us? Because no national economy produces all the goods and services that its people need. In fact, countries have been trading for thousands of years. Marco Polo established trade between Europe and China in the late thirteenth century, introducing gun powder to China and citrus and spices to Europe.[1] Countries are importers when they buy goods and services from other countries; when they sell products to other nations, they’re exporters. (We’ll discuss importing and exporting in greater detail later in the chapter.) The monetary value of international trade is enormous. In 2018, the total value of worldwide trade in merchandise and commercial services was $19.5 trillion. In comparison, this figure stood at around 6.45 trillion US dollars in 2000.[2]

Absolute and Comparative Advantage

To understand why certain countries import or export certain products, you need to realize that every country (or region) can’t produce the same products. The cost of labor, the availability of natural resources, and the level of know-how vary greatly around the world. Most economists use the concepts of absolute advantage and comparative advantage to explain why countries import some products and export others.

Absolute Advantage

A nation has an absolute advantage if (1) it’s the only source of a particular product or (2) it can make more of a product using fewer resources than other countries. Because of climate and soil conditions, for example, France had an absolute advantage in wine making until its dominance of worldwide wine production was challenged by the growing wine industries in Italy, Spain, and the United States. Unless an absolute advantage is based on some limited natural resource, it seldom lasts. That’s why there are few, if any, examples of absolute advantage in the world today.

Comparative Advantage

How can we predict, for any given country, which products will be made and sold at home, which will be imported, and which will be exported? This question can be answered by looking at the concept of comparative advantage, which exists when a country can produce a product at a lower opportunity cost compared to another nation. But what’s an opportunity cost? Opportunity costs are the products that a country must forego making in order to produce something else. When a country decides to specialize in a particular product, it must sacrifice the production of another product. Countries benefit from specialization—focusing on what they do best, and trading the output to other countries for what those countries do best. The United States, for instance, is increasingly an exporter of knowledge-based products, such as software, movies, music, and professional services (management consulting, financial services, and so forth). America’s colleges and universities, therefore, are a source of comparative advantage, and students from all over the world come to the United States for the world’s best higher-education system.

France and Italy are centers for fashion and luxury goods and are leading exporters of wine, perfume, and designer clothing. Japan’s engineering expertise has given it an edge in such fields as automobiles and consumer electronics. And with large numbers of highly skilled graduates in technology, India has become the world’s leader in low-cost, computer-software engineering.

How Do We Measure Trade Between Nations?

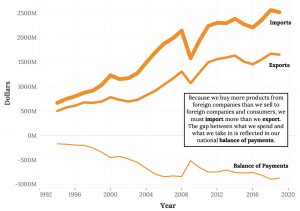

To evaluate the nature and consequences of its international trade, a nation looks at two key indicators. We determine a country’s balance of trade by subtracting the value of its imports from the value of its exports. If a country sells more products than it buys, it has a favorable balance, called a trade surplus. If it buys more than it sells, it has an unfavorable balance, or a trade deficit.

For many years, the United States has had a trade deficit: we buy far more goods from the rest of the world than we sell overseas. This fact shouldn’t be surprising. With high income levels, we not only consume a sizable portion of our own domestically produced goods but enthusiastically buy imported goods. Other countries, such as China and Taiwan, which manufacture high volumes for export, have large trade surpluses because they sell far more goods overseas than they buy.

Managing the National Credit Card

Are trade deficits a bad thing? Not necessarily. They can be positive if a country’s economy is strong enough both to keep growing and to generate the jobs and incomes that permit its citizens to buy the best the world has to offer. That was certainly the case in the United States in the 1990s. Some experts, however, are alarmed at our trade deficit. Investment guru Warren Buffet, for example, cautions that no country can continuously sustain large and burgeoning trade deficits. Why not? Because creditor nations will eventually stop taking IOUs from debtor nations, and when that happens, the national spending spree will have to cease. “Our national credit card,” he warns, “allows us to charge truly breathtaking amounts. But that card’s credit line is not limitless.”[3]

By the same token, trade surpluses aren’t necessarily good for a nation’s consumers. Japan’s export-fueled economy produced high economic growth in the 1970s and 1980s. But most domestically made consumer goods were priced at artificially high levels inside Japan itself—so high, in fact, that many Japanese traveled overseas to buy the electronics and other high-quality goods on which Japanese trade was dependent.

CD players and televisions were significantly cheaper in Honolulu or Los Angeles than in Tokyo. How did this situation come about? Though Japan manufactures a variety of goods, many of them are made for export. To secure shares in international markets, Japan prices its exported goods competitively. Inside Japan, because competition is limited, producers can put artificially high prices on Japanese-made goods. Due to a number of factors (high demand for a limited supply of imported goods, high shipping and distribution costs, and other costs incurred by importers in a nation that tends to protect its own industries), imported goods are also expensive.[4]

Balance of Payments

The second key measure of the effectiveness of international trade is balance of payments: the difference, over a period of time, between the total flow of money coming into a country and the total flow of money going out. As in its balance of trade, the biggest factor in a country’s balance of payments is the money that flows as a result of imports and exports. But balance of payments includes other cash inflows and outflows, such as cash received from or paid for foreign investment, loans, tourism, military expenditures, and foreign aid. For example, if a US company buys some real estate in a foreign country, that investment counts in the US balance of payments, but not in its balance of trade, which measures only import and export transactions. In the long run, having an unfavorable balance of payments can negatively affect the stability of a country’s currency. The United States has experienced unfavorable balances of payments since the 1970s which has forced the government to cover its debt by borrowing from other countries.[5] Figure 5.2 provides a brief historical overview to illustrate the relationship between the United States’ balance of trade and its balance of payments.

Opportunities in International Business

The fact that nations exchange billions of dollars in goods and services each year demonstrates that international trade makes good economic sense. For a company wishing to expand beyond national borders, there are a variety of ways it can get involved in international business. Let’s take a closer look at the more popular ones.

Importing and Exporting

Importing (buying products overseas and reselling them in one’s own country) and exporting (selling domestic products to foreign customers) are the oldest and most prevalent forms of international trade. For many companies, importing is the primary link to the global market. American food and beverage wholesalers, for instance, import for resale in US supermarkets the bottled waters Evian and Fiji from their sources in the French Alps and the Fiji Islands respectively.[6] Other companies get into the global arena by identifying an international market for their products and becoming exporters. The Chinese, for instance, are fond of fast foods cooked in soybean oil. Because they also have an increasing appetite for meat, they need high-protein soybeans to raise livestock.[7] American farmers exported over $9 billion worth of soybeans to China in 2010 to nearly $21 billion in 2017.[8]

Licensing and Franchising

A company that wants to get into an international market quickly while taking only limited financial and legal risks might consider licensing agreements with foreign companies. An international licensing agreement allows a foreign company (the licensee) to sell the products of a producer (the licensor) or to use its intellectual property (such as patents, trademarks, copyrights) in exchange for what is known as royalty fees. Here’s how it works: You own a company in the United States that sells coffee-flavored popcorn. You’re sure that your product would be a big hit in Japan, but you don’t have the resources to set up a factory or sales office in that country. You can’t make the popcorn here and ship it to Japan because it would get stale. So you enter into a licensing agreement with a Japanese company that allows your licensee to manufacture coffee-flavored popcorn using your special process and to sell it in Japan under your brand name. In exchange, the Japanese licensee would pay you a royalty fee—perhaps a percentage of each sale or a fixed amount per unit.

Another popular way to expand overseas is to sell franchises. Under an international franchise agreement, a company (the franchiser) grants a foreign company (the franchisee) the right to use its brand name and to sell its products or services. The franchisee is responsible for all operations but agrees to operate according to a business model established by the franchiser. In turn, the franchiser usually provides advertising, training, and new-product assistance. Franchising is a natural form of global expansion for companies that operate domestically according to a franchise model, including restaurant chains, such as McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken, and hotel chains, such as Holiday Inn and Best Western.

Contract Manufacturing and Outsourcing

Because of high domestic labor costs, many US companies manufacture their products in countries where labor costs are lower. This arrangement is called international contract manufacturing, a form of outsourcing. A US company might contract with a local company in a foreign country to manufacture one of its products. It will, however, retain control of product design and development and put its own label on the finished product. Contract manufacturing is quite common in the US apparel business, with most American brands being made in a number of Asian countries, including China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India.[9]

Thanks to twenty-first-century information technology, non-manufacturing functions can also be outsourced to nations with lower labor costs. US companies increasingly draw on a vast supply of relatively inexpensive skilled labor to perform various business services, such as software development, accounting, and claims processing. For years, American insurance companies have processed much of their claims-related paperwork in Ireland. With a large, well-educated population with English language skills, India has become a center for software development and customer-call centers for American companies. In the case of India, as you can see in Figure 5.4, the attraction is not only a large pool of knowledge workers but also significantly lower wages.

| Occupation | US Wage per Hour (per year) | Indian Wage per Hour (per year) |

|---|---|---|

| Accountant | $22.12 per hour (~$44,240 per year) | $3.15 per hour (~$6,300 per year) |

| Information Technology Consultant | $40.70 per hour (~$81,400 per year) | $22.40 per hour (~$44,800 per year) |

| Cleaner | $8.70 per hour (~$17,400 per year) | $2.10 per hour (~$4,200 per year) |

Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

What if a company wants to do business in a foreign country but lacks the expertise or resources? Or what if the target nation’s government doesn’t allow foreign companies to operate within its borders unless it has a local partner? In these cases, a firm might enter into a strategic alliance with a local company or even with the government itself.

A strategic alliance is an agreement between two companies (or a company and a nation) to pool resources in order to achieve business goals that benefit both partners. For example, Korean automaker Hyundai Motor Co agreed to jointly develop electric vehicles with California startup Canoo in addition to investing $110 million in UK startup Arrival to jointly develop electric commercial vehicles. [10]

An alliance can serve a number of purposes:

- Enhancing marketing efforts

- Building sales and market share

- Improving products

- Reducing production and distribution costs

- Sharing technology

Alliances range in scope from informal cooperative agreements to joint ventures—alliances in which the partners fund a separate entity (perhaps a partnership or a corporation) to manage their joint operation. Magazine publisher Hearst, for example, has joint ventures with companies in several countries. So, young women in Israel can read Cosmo Israel in Hebrew, and Russian women can pick up a Russian-language version of Cosmo that meets their needs. The US edition serves as a starting point to which nationally appropriate material is added in each different nation. This approach allows Hearst to sell the magazine in more than 50 countries.[11]

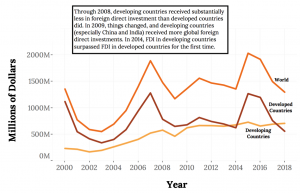

Foreign Direct Investment and Subsidiaries

Many of the approaches to global expansion that we’ve discussed so far allow companies to participate in international markets without investing in foreign plants and facilities. As markets expand, however, a firm might decide to enhance its competitive advantage by making a direct investment in operations conducted in another country. Foreign direct investment (FDI) refers to the formal establishment of business operations on foreign soil—the building of factories, sales offices, and distribution networks to serve local markets in a nation other than the company’s home country. On the other hand, offshoring occurs when the facilities set up in the foreign country replace US manufacturing facilities and are used to produce goods that will be sent back to the United States for sale. Shifting production to low-wage countries is often criticized as it results in the loss of jobs for US workers.[12]

FDI is generally the most expensive commitment that a firm can make to an overseas market, and it’s typically driven by the size and attractiveness of the target market. For example, German and Japanese automakers, such as BMW, Mercedes, Toyota, and Honda, have made serious commitments to the US market: most of the cars and trucks that they build in plants in the South and Midwest are destined for sale in the United States.

A common form of FDI is the foreign subsidiary: an independent company owned by a foreign firm (called the parent). This approach to going international not only gives the parent company full access to local markets but also exempts it from any laws or regulations that may hamper the activities of foreign firms. The parent company has tight control over the operations of a subsidiary, but while senior managers from the parent company often oversee operations, many managers and employees are citizens of the host country. Not surprisingly, most very large firms have foreign subsidiaries. IBM and Coca-Cola, for example, have both had success in the Japanese market through their foreign subsidiaries (IBM–Japan and Coca-Cola–Japan). FDI goes in the other direction, too, and many companies operating in the United States are in fact subsidiaries of foreign firms. Gerber Products, for example, is a subsidiary of the Swiss company Novartis, while Stop & Shop and Giant Food Stores belong to the Dutch company Royal Ahold. Where does most FDI capital end up? Figure 5.5 provides an overview of amounts, destinations (high to low income countries), and trends.

All these strategies have been employed successfully in global business. But success in international business involves more than finding the best way to reach international markets. Global business is a complex, risky endeavor. Over time, many large companies reach the point of becoming truly multi-national.

| Company | Industry | Headquarters | Revenue in 2014 (in billions) | Revenue in 2019 (in billions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wal Mart | General Merchandise | USA | $485.7 | $514.4 |

| 2. Sinopec Group | Petroleum | China | $446.8 | $414.6 |

| 3. Royal Dutch Shell | Petroleum | Netherlands/Great Britain | $431.3 | $396.6 |

| 4. China National Petroleum | Petroleum | China | $428.6 | $393 |

| 5. State Grid | Utilities | China | $339.4 | $387.1 |

| 6. Saudi Aramco | Petroleum | Saudi Arabia | N/A* | $355.9 |

| 7. BP | Petroleum | Great Britain | $358.7 | $303.7 |

| 8. Exxon Mobil | Petroleum | USA | $382.6 | $290.2 |

| 9. Volkswagen | Automobile | Germany | $268.6 | $278.3 |

| 10. Toyota Motor | Automobile | Japan | $247.7 | $272.6 |

| 11. Apple | Computers | USA | $182.8 | $265.6 |

| 12. Berkshire Hathaway | Insurance | USA | $194.7 | $247.8 |

| 13. Amazon.com | Internet Services and Retailing | USA | $74.5 | $232.9 |

| 14. UnitedHealth Group | Health Care | USA | $122.5 | $226.2 |

| 15. Samsung Electronics | Electronics | South Korea | $195.8 | $221.6 |

Multinational Corporations

A company that operates in many countries is called a multinational corporation (MNC). Fortune magazine’s roster of the top 500 MNCs speaks for the growth of non-US businesses. Only two of the top 10 MNCs are headquartered in the US (see Figure 5.6 above): Wal-Mart (number 1) and Exxon (number 8). Four others are in the top 15: Apple, Berkshire Hathaway, Amazon, and UnitedHealth Group. The others are non-US firms. Interestingly, of the 15 top companies, seven are energy suppliers, two are motor vehicle companies, and two are consumer electronics or computer companies. Also interesting is the difference between company revenues and profits: the list would look quite different arranged by profits instead of revenues!

MNCs often adopt the approach encapsulated in the motto “Think globally, act locally.” They often adjust their operations, products, marketing, and distribution to mesh with the environments of the countries in which they operate. Because they understand that a “one-size-fits-all” mentality doesn’t make good business sense when they’re trying to sell products in different markets, they’re willing to accommodate cultural and economic differences. Increasingly, MNCs supplement their mainstream product line with products designed for local markets. Coca-Cola, for example, produces coffee and citrus-juice drinks developed specifically for the Japanese market.[13] When Nokia and Motorola design cell phones, they’re often geared to local tastes in color, size, and other features. For example, Nokia introduced a cell phone for the rural Indian consumer that has a dust-resistant keypad, anti-slip grip, and a built-in flashlight.[14] McDonald’s provides a vegetarian menu in India, where religious convictions affect the demand for beef and pork.[15] In Germany, McDonald’s caters to local tastes by offering beer in some restaurants and a Shrimp Burger in Hong Kong and Japan.[16]

Likewise, many MNCs have made themselves more sensitive to local market conditions by decentralizing their decision making. While corporate headquarters still maintain a fair amount of control, home-country managers keep a suitable distance by relying on modern telecommunications. Today, fewer managers are dispatched from headquarters; MNCs depend instead on local talent. Not only does decentralized organization speed up and improve decision making, but it also allows an MNC to project the image of a local company. IBM, for instance, has been quite successful in the Japanese market because local customers and suppliers perceive it as a Japanese company. Crucial to this perception is the fact that the vast majority of IBM’s Tokyo employees, including top leadership, are Japanese nationals.[17]

Criticism of MNCs

The global reach of MNCs is a source of criticism as well as praise. Critics argue that they often destroy the livelihoods of home-country workers by moving jobs to developing countries where workers are willing to labor under poor conditions and for less pay. They also contend that traditional lifestyles and values are being weakened, and even destroyed, as global brands foster a global culture of American movies; fast food; and cheap, mass-produced consumer products. Still others claim that the demand of MNCs for constant economic growth and cheaper access to natural resources do irreversible damage to the physical environment. All these negative consequences, critics maintain, stem from the abuses of international trade—from the policy of placing profits above people, on a global scale. These views surfaced in violent street demonstrations in Seattle in 1999 and Genoa, Italy, in 2000, and since then, meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank have regularly been assailed by protestors.

In Defense of MNCs

Supporters of MNCs respond that huge corporations deliver better, cheaper products for customers everywhere; create jobs; and raise the standard of living in developing countries. They also argue that globalization increases cross-cultural understanding. Anne O. Kruger, first deputy managing director of the IMF, says the following:

“The impact of the faster growth on living standards has been phenomenal. We have observed the increased well-being of a larger percentage of the world’s population by a greater increment than ever before in history. Growing incomes give people the ability to spend on things other than basic food and shelter, in particular on things such as education and health. This ability, combined with the sharing among nations of medical and scientific advances, has transformed life in many parts of the developing world.

Infant mortality has declined from 180 per 1,000 births in 1950 to 60 per 1,000 births. Literacy rates have risen from an average of 40 percent in the 1950s to over 70 percent today. World poverty has declined, despite still-high population growth in the developing world.”[18]

The Global Business Environment

In the classic movie The Wizard of Oz, a magically misplaced Midwest farm girl takes a moment to survey the bizarre landscape of Oz and then comments to her little dog, “I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore, Toto.” That sentiment probably echoes the reaction of many businesspeople who find themselves in the midst of international ventures for the first time. The differences between the foreign landscape and the one with which they’re familiar are often huge and multifaceted. Some are quite obvious, such as differences in language, currency, and everyday habits (say, using chopsticks instead of silverware). But others are subtle, complex, and sometimes even hidden.

Success in international business means understanding a wide range of cultural, economic, legal, and political differences between countries. Let’s look at some of the more important of these differences.

The Cultural Environment

Even when two people from the same country communicate, there’s always a possibility of misunderstanding. When people from different countries get together, that possibility increases substantially. Differences in communication styles reflect differences in culture: the system of shared beliefs, values, customs, and behaviors that govern the interactions of members of a society. Cultural differences create challenges to successful international business dealings. Let’s look at a few of these challenges.

Language

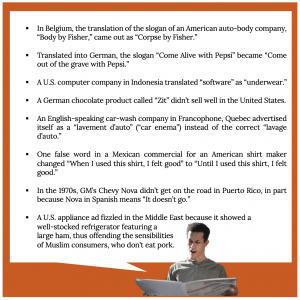

English is the international language of business. The natives of such European countries as France and Spain certainly take pride in their own languages and cultures, but nevertheless English is the business language of the European community.

Whereas only a few educated Europeans have studied Italian or Norwegian, most have studied English. Similarly, on the South Asian subcontinent, where hundreds of local languages and dialects are spoken, English is the official language. In most corners of the world, English-only speakers—such as most Americans—have no problem finding competent translators and interpreters. So why is language an issue for English speakers doing business in the global marketplace? In many countries, only members of the educated classes speak English. The larger population—which is usually the market you want to tap—speaks the local tongue. Advertising messages and sales appeals must take this fact into account. More than one English translation of an advertising slogan has resulted in a humorous (and perhaps serious) blunder. Some classics are listed on the next page in Figure 5.7.

Furthermore, relying on translators and interpreters puts you as an international businessperson at a disadvantage. You’re privy only to interpretations of the messages that you’re getting, and this handicap can result in a real competitive problem. Maybe you’ll misread the subtler intentions of the person with whom you’re trying to conduct business. The best way to combat this problem is to study foreign languages. Most people appreciate some effort to communicate in their local language, even on the most basic level. They even appreciate mistakes you make resulting from a desire to demonstrate your genuine interest in the language of your counterparts in foreign countries. The same principle goes doubly when you’re introducing yourself to non-English speakers in the United States. Few things work faster to encourage a friendly atmosphere than a native speaker’s willingness to greet a foreign guest in the guest’s native language.

Time and Sociability

Americans take for granted many of the cultural aspects of our business practices. Most of our meetings, for instance, focus on business issues, and we tend to start and end our meetings on schedule. These habits stem from a broader cultural preference: we don’t like to waste time. (It was an American, Benjamin Franklin, who coined the phrase “Time is money.”) This preference, however, is by no means universal. The expectation that meetings will start on time and adhere to precise agendas is common in parts of Europe (especially the Germanic countries), as well as in the United States, but elsewhere—say, in Latin America and the Middle East—people are often late to meetings and it is an acceptable custom.

High- and Low-Context Cultures

Likewise, don’t expect businesspeople from these regions—or businesspeople from most of Mediterranean Europe, for that matter—to “get down to business” as soon as a meeting has started. They’ll probably ask about your health and that of your family, inquire whether you’re enjoying your visit to their country, suggest local foods, and generally appear to be avoiding serious discussion at all costs. For Americans, such topics are conducive to nothing but idle chitchat, but in certain cultures, getting started this way is a matter of simple politeness and hospitality and expected.

Intercultural Communication

Different cultures have different communication styles—a fact that can take some getting used to. For example, degrees of animation in expression can vary from culture to culture. Southern Europeans and Middle Easterners are quite animated, favoring expressive body language along with hand gestures and raised voices. Northern Europeans are far more reserved. The English, for example, are famous for their understated style and the Germans for their formality in most business settings. In addition, the distance at which one feels comfortable when talking with someone varies by culture. People from the Middle East like to converse from a distance of a foot or less, while Americans prefer more personal space.

Finally, while people in some cultures prefer to deliver direct, clear messages, others use language that’s subtler or more indirect. North Americans and most Northern Europeans fall into the former category and many Asians into the latter. But even within these categories, there are differences. Though typically polite, Chinese and Koreans are extremely direct in expression, while Japanese are indirect: They use vague language and avoid saying “no” even if they do not intend to do what you ask. They worry that turning someone down will result in their “losing face,” i.e., an embarrassment or loss of credibility, and so they avoid doing this in public.

In summary, learn about a country’s culture and use your knowledge to help improve the quality of your business dealings. Learn to value the subtle differences among cultures, but don’t allow cultural stereotypes to dictate how you interact with people from any culture. Treat each person as an individual and spend time getting to know what he or she is about.

The Economic Environment

If you plan to do business in a foreign country, you need to know its level of economic development. You also should be aware of factors influencing the value of its currency and the impact that changes in that value will have on your profits.

Economic Development

If you don’t understand a nation’s level of economic development, you’ll have trouble answering some basic questions, such as: Will consumers in this country be able to afford the product I want to sell? Will it be possible to make a reasonable profit? A country’s level of economic development can be evaluated by estimating the annual income earned per citizen. The World Bank, which lends money for improvements in underdeveloped nations, divides countries into four income categories:

World Bank Country and Lending Groups (by Gross National Income per Capita 2021)[19]

- High income—$12,536 or higher (United States, Germany, Japan)

- Upper-middle income—$4,046 to $12,535 (China, South Africa, Mexico)

- Lower-middle income—$1,036 to $4,045 (Kenya, Philippines, India)

- Low income—$1,035 or less (Afghanistan, South Sudan, Haiti)

Note that that even though a country has a low annual income per citizen, it can still be an attractive place for doing business. India, for example, is a lower-middle-income country, yet it has a population of a billion, and a segment of that population is well educated—an appealing feature for many business initiatives.

The long-term goal of many countries is to move up the economic development ladder. Some factors conducive to economic growth include a reliable banking system, a strong stock market, and government policies to encourage investment and competition while discouraging corruption. It’s also important that a country have a strong infrastructure—its systems of communications (telephone, Internet, television, newspapers), transportation (roads, railways, airports), energy (gas and electricity, power plants), and social facilities (schools, hospitals). These basic systems will help countries attract foreign investors, which can be crucial to economic development.

Currency Valuations and Exchange Rates

If every nation used the same currency, international trade and travel would be a lot easier. Of course, this is not the case. There are around 175 currencies in the world: Some you’ve heard of, such as the British pound; others are likely unknown to you, such as the manat, the official currency of Azerbaijan. If you were in Azerbaijan you would exchange your US dollars for Azerbaijan manats. The day’s foreign exchange rate will tell you how much one currency is worth relative to another currency and so determine how many manats you will receive. If you have traveled abroad, you already have personal experience with the impact of exchange rate movements.

The Legal and Regulatory Environment

One of the more difficult aspects of doing business globally is dealing with vast differences in legal and regulatory environments. The United States, for example, has an established set of laws and regulations that provide direction to businesses operating within its borders. But because there is no global legal system, key areas of business law—for example, contract provisions and copyright protection—can be treated in different ways in different countries. Companies doing international business often face many inconsistent laws and regulations. To navigate this sea of confusion, American business people must know and follow both US laws and regulations and those of nations in which they operate.

Business history is filled with stories about American companies that have stumbled in trying to comply with foreign laws and regulations. Coca-Cola, for example, ran afoul of Italian law when it printed its ingredients list on the bottle cap rather than on the bottle itself. Italian courts ruled that the labeling was inadequate because most people throw the cap away.[20]

One approach to dealing with local laws and regulations is hiring lawyers from the host country who can provide advice on legal issues. Another is working with local businesspeople who have experience in complying with regulations and overcoming bureaucratic obstacles.

Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

One US law that creates unique challenges for American firms operating overseas is the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which prohibits the distribution of bribes and other favors in the conduct of business. Unfortunately, though they’re illegal in this country, such tactics as kickbacks and bribes are business-as-usual in many nations. According to some experts, American businesspeople are at a competitive disadvantage if they’re prohibited from giving bribes or undercover payments to foreign officials or business people who expect them. In theory, because the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act warns foreigners that Americans can’t give bribes, they’ll eventually stop expecting them.

Where are American businesspeople most likely and least likely to encounter bribe requests and related forms of corruption? Transparency International, an independent German-based organization, annually rates nations according to “perceived corruption,” (see Figure 5.8) which it defines as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.”[21]

| Rank | Country | CPI Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | New Zealand | 87 |

| 1 | Denmark | 87 |

| 3 | Finland | 86 |

| 4 | Switzerland | 85 |

| 12 | United Kingdom | 77 |

| 23 | United States | 69 |

| 130 | Mexico | 29 |

| 172 | North Korea | 17 |

| 173 | Sudan | 16 |

| 180 | Somalia | 9 |

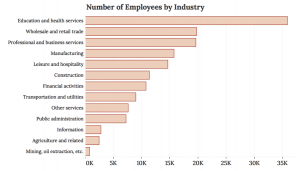

Case Study: Economic and International Impact of the US Hospitality & Tourism

According to the US International Trade Administration, the travel and tourism industry in the United States generated $1.6 trillion in economic output and 7.8 million US jobs in 2013, with nearly 1 in 18 Americans employed directly or indirectly in a travel or tourism-related industry.[22] The Bureau of Labor of Labor Statistics indicates that an even higher percentage (11 percent) of US jobs are in the Leisure and Hospitality sector.[23]

While the majority of travel, tourism and hospitality in the US tourism industry is domestic, the US leads the world in international travel and tourism exports (i.e., travelers from other countries visiting the United States) with 15 percent of global traveler spending. Travel and tourism ranks as the top services export, accounting for 31 percent of all US services exports in 2014.

Expenditures by international visitors in the United States translate to economic impacts and jobs: including: $220.8 billion in sales, a $75.1 billion trade surplus, and 1.1 million total jobs in 2014.[24] The sector is poised to grow: the latest US Commerce Department international travel forecast estimates a 20 percent increase in international visitors in 2020 in comparison to 2014.[25]

Trade Controls

The debate about the extent to which countries should control the flow of foreign goods and investments across their borders is as old as international trade itself. Governments continue to control trade. To better understand how and why, let’s examine a hypothetical case. Suppose you’re in charge of a small country in which people do two things—grow food and make clothes. Because the quality of both products is high and the prices are reasonable, your consumers are happy to buy locally made food and clothes. But one day, a farmer from a nearby country crosses your border with several wagonloads of wheat to sell. On the same day, a foreign clothes maker arrives with a large shipment of clothes. These two entrepreneurs want to sell food and clothes in your country at prices below those that local consumers now pay for domestically made food and clothes. At first, this seems like a good deal for your consumers: they won’t have to pay as much for food and clothes. But then you remember all the people in your country who grow food and make clothes. If no one buys their goods (because the imported goods are cheaper), what will happen to their livelihoods? And if many people become unemployed, what will happen to your national economy? That’s when you decide to protect your farmers and clothes makers by setting up trade rules. Maybe you’ll increase the prices of imported goods by adding a tax to them; you might even make the tax so high that they’re more expensive than your homemade goods. Or perhaps you’ll help your farmers grow food more cheaply by giving them financial help to defray their costs. The government payments that you give to the farmers to help offset some of their costs of production are called subsidies. These subsidies will allow the farmers to lower the price of their goods to a point below that of imported competitors’ goods. What’s even better is that the lower costs will allow the farmers to export their own goods at attractive, competitive prices.

The United States has a long history of subsidizing farmers. Subsidy programs guarantee farmers (including large corporate farms) a certain price for their crops, regardless of the market price. This guarantee ensures stable income in the farming community but can have a negative impact on the world economy. How? Critics argue that in allowing American farmers to export crops at artificially low prices, US agricultural subsidies permit them to compete unfairly with farmers in developing countries. A reverse situation occurs in the steel industry, in which a number of countries—China, Japan, Russia, Germany, and Brazil—subsidize domestic producers.

US trade unions charge that this practice gives an unfair advantage to foreign producers and hurts the American steel industry, which can’t compete on price with subsidized imports.

Whether they push up the price of imports or push down the price of local goods, such initiatives will help locally produced goods compete more favorably with foreign goods. Both strategies are forms of trade controls—policies that restrict free trade. Because they protect domestic industries by reducing foreign competition, the use of such controls is often called protectionism. Though there’s considerable debate over the pros and cons of this practice, all countries engage in it to some extent. Before debating the issue, however, let’s learn about the more common types of trade restrictions: tariffs, quotas, and, embargoes.

Tariffs

Tariffs are taxes on imports. Because they raise the price of the foreign-made goods, they make them less competitive. The United States, for example, protects domestic makers of synthetic knitted shirts by imposing a stiff tariff of 32.5 percent on imports.[26] Tariffs are also used to raise revenue for a government. Shoe imports alone are worth $2.7 billion annually to the federal government.[27]

In 2018 and 2019, the United States government implemented a round of four different tariffs meant to reduce the trade deficit along with punishing China for alleged unfair trading practices and intellectual property theft. The US imposed tariffs on more than $360 billion worth of Chinese goods which then triggered a similar response from the Chinese government with tariffs on more than $110 billon of US made products. This US–China trade war led to uncertainties not only in both markets but globally as well. Finally, in January 2020, the two governments reached a tentative trade agreement that still required more negotiations.

Quotas

A quota imposes limits on the quantity of a good that can be imported over a period of time. Quotas are used to protect specific industries, usually new industries or those facing strong competitive pressure from foreign firms. US import quotas take two forms. An absolute quota fixes an upper limit on the amount of a good that can be imported during the given period. A tariff-rate quota permits the import of a specified quantity and then adds a high import tax once the limit is reached.

Sometimes quotas protect one group at the expense of another. To protect sugar beet and sugar cane growers, for instance, the United States imposes a tariff-rate quota on the importation of sugar—a policy that has driven up the cost of sugar to two to three times world prices.[28] These artificially high prices push up costs for American candy makers, some of whom have moved their operations elsewhere, taking high-paying manufacturing jobs with them. Life Savers, for example, were made in the United States for 90 years but are now produced in Canada, where the company saves $9 million annually on the cost of sugar.[29]

An extreme form of quota is the embargo, which, for economic or political reasons, bans the import or export of certain goods to or from a specific country. The United States, for example, bans nearly every commodity originating in Cuba, although this may soon change.

Dumping

A common political rationale for establishing tariffs and quotas is the need to combat dumping: the practice of selling exported goods below the price that producers would normally charge in their home markets (and often below the cost of producing the goods). Usually, nations resort to this practice to gain entry and market share in foreign markets, but it can also be used to sell off surplus or obsolete goods. Dumping creates unfair competition for domestic industries, and governments are justifiably concerned when they suspect foreign countries of dumping products on their markets. They often retaliate by imposing punitive tariffs that drive up the price of the imported goods.

The Pros and Cons of Trade Controls

Opinions vary on government involvement in international trade. Proponents of controls contend that there are a number of legitimate reasons why countries engage in protectionism. Sometimes they restrict trade to protect specific industries and their workers from foreign competition—agriculture, for example, or steel making. At other times, they restrict imports to give new or struggling industries a chance to get established. Finally, some countries use protectionism to shield industries that are vital to their national defense, such as shipbuilding and military hardware.

Despite valid arguments made by supporters of trade controls, most experts believe that such restrictions as tariffs and quotas—as well as practices that don’t promote level playing fields, such as subsidies and dumping—are detrimental to the world economy. Without impediments to trade, countries can compete freely. Each nation can focus on what it does best and bring its goods to a fair and open world market. When this happens, the world will prosper, or so the argument goes. International trade is certainly heading in the direction of unrestricted markets.

Reducing International Trade Barriers

A number of organizations work to ease barriers to trade, and more countries are joining together to promote trade and mutual economic benefits. Let’s look at some of these important initiatives.

Trade Agreements and Organizations

Free trade is encouraged by a number of agreements and organizations set up to monitor trade policies. The two most important are the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

After the Great Depression and World War II, most countries focused on protecting home industries, so international trade was hindered by rigid trade restrictions. To rectify this situation, 23 nations joined together in 1947 and signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which encouraged free trade by regulating and reducing tariffs and by providing a forum for resolving trade disputes.

The highly successful initiative achieved substantial reductions in tariffs and quotas, and in 1995 its members founded the World Trade Organization to continue the work of GATT in overseeing global trade.

World Trade Organization

Based in Geneva, Switzerland, with nearly 150 members, the World Trade Organization (WTO) encourages global commerce and lower trade barriers, enforces international rules of trade, and provides a forum for resolving disputes. It is empowered, for instance, to determine whether a member nation’s trade policies have violated the organization’s rules, and it can direct “guilty” countries to remove disputed barriers (though it has no legal power to force any country to do anything it doesn’t want to do). If the guilty party refuses to comply, the WTO may authorize the plaintiff nation to erect trade barriers of its own, generally in the form of tariffs.

Affected members aren’t always happy with WTO actions. For example, the European Commission is having to wait on a WTO action regarding whether it can impose tariffs against the United States over subsidies for Boeing (BA.N). They claim it is unjustified and harms the bloc’s right to retaliate.[30]

Financial Support for Emerging Economies: The IMF and the World Bank

A key to helping developing countries become active participants in the global marketplace is providing financial assistance. Offering monetary assistance to some of the poorest nations in the world is the shared goal of two organizations: the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. These organizations, to which most countries belong, were established in 1944 to accomplish different but complementary purposes.

The International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans money to countries with troubled economies, such as Mexico in the 1980s and mid-1990s and Russia and Argentina in the late 1990s. There are, however, strings attached to IMF loans: in exchange for relief in times of financial crisis, borrower countries must institute sometimes painful financial and economic reforms. In the 1980s, for example, Mexico received financial relief from the IMF on the condition that it privatize and deregulate certain industries and liberalize trade policies. The government was also required to cut back expenditures for such services as education, health care, and workers’ benefits.[31]

The World Bank

The World Bank is an important source of economic assistance for poor and developing countries. With backing from wealthy donor countries (such as the United States, Japan, Germany, and United Kingdom), the World Bank has committed $42.5 billion in loans, grants, and guarantees to some of the world’s poorest nations.[32] Loans are made to help countries improve the lives of the poor through community-support programs designed to provide health, nutrition, education, infrastructure, and other social services.

Trading Blocs: NAFTA and the European Union

So far, our discussion has suggested that global trade would be strengthened if there were no restrictions on it—if countries didn’t put up barriers to trade or perform special favors for domestic industries. The complete absence of barriers is an ideal state of affairs that we haven’t yet attained. In the meantime, economists and policymakers tend to focus on a more practical question: Can we achieve the goal of free trade on the regional level? To an extent, the answer is yes. In certain parts of the world, groups of countries have joined together to allow goods and services to flow without restrictions across their mutual borders. Such groups are called trading blocs. Let’s examine two of the most powerful trading blocs—NAFTA and the European Union.

North American Free Trade Association

The North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA) is an agreement among the governments of the United States, Canada, and Mexico to open their borders to unrestricted trade. The effect of this agreement is that three very different economies are combined into one economic zone with almost no trade barriers. From the northern tip of Canada to the southern tip of Mexico, each country benefits from the comparative advantages of its partners: each nation is free to produce what it does best and to trade its goods and services without restrictions.

When the agreement was ratified in 1994, it had no shortage of skeptics. Many people feared, for example, that without tariffs on Mexican goods, more US manufacturing jobs would be lost to Mexico, where labor is cheaper. Almost two decades later, most such fears have not been realized, and, by and large, NAFTA has been a success.

Since it went into effect, the value of trade between the United States and Mexico has grown substantially, and Canada and Mexico are now the United States’ top trading partners.

Shortly after taking office in 2017, concerned with deficiencies and mistakes from the original NAFTA, President Trump and representatives from the Office of the United States Trade Representative, began negotiating a new trade agreement between the United States, Mexico and Canada. Signed in 2018 and later ratified by all three nations, the new United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) replaces the 25-year-old trade agreement known as NAFTA. Implemented in July 2020, the USMCA works to mutually beneficial trade between all three nations with the goal of leading to freer markets, fairer trade, and robust economic growth in North America.[33]

The European Union

The forty-plus countries of Europe have long shown an interest in integrating their economies. The first organized effort to integrate a segment of Europe’s economic entities began in the late 1950s, when six countries joined together to form the European Economic Community (EEC). Over the next four decades, membership grew, and in the late 1990s, the EEC became the European Union. Today, the European Union (EU) is a group of 27 countries that have eliminated trade barriers among themselves (see the map in Figure 5.10).

At first glance, the EU looks similar to NAFTA. Both, for instance, allow unrestricted trade among member nations. But the provisions of the EU go beyond those of NAFTA in several important ways. Most importantly, the EU is more than a trading organization: it also enhances political and social cooperation and binds its members into a single entity with authority to require them to follow common rules and regulations. It is much like a federation of states with a weak central government, with the effect not only of eliminating internal barriers but also of enforcing common tariffs on trade from outside the EU. In addition, while NAFTA allows goods and services as well as capital to pass between borders, the EU also allows people to come and go freely: if you possess an EU passport, you can work in any EU nation.

The Euro

A key step toward unification occurred in 1999, when most (but not all) EU members agreed to abandon their own currencies and adopt a joint currency. The actual conversion occurred in 2002, when a common currency called the euro replaced the separate currencies of participating EU countries. The common currency facilitates trade and finance because exchange-rate differences no longer complicate transactions.[34]

Its proponents argued that the EU would not only unite economically and politically distinct countries but also create an economic power that could compete against the dominant players in the global marketplace. Individually, each European country has limited economic power, but as a group, they could be an economic superpower.[35] Over time, the value of the euro has been questioned. Many of the “euro” countries (Spain, Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Ireland in particular) have been financially irresponsible, piling up huge debts and experiencing high unemployment and problems in the housing market. But because these troubled countries share a common currency with the other “euro countries,” they are less able to correct their economic woes.[36] Many economists fear that the financial crisis precipitated by these financially irresponsible countries threaten the very survival of the euro.[37] Keep a close eye on Greece because if an exit from the Euro occurs, it will likely start there.

Only time will tell whether the trend toward regional trade agreements is good for the world economy. Clearly, they’re beneficial to their respective participants; for one thing, they get preferential treatment from other members. But certain questions still need to be answered more fully. Are regional agreements, for example, moving the world closer to free trade on a global scale—toward a marketplace in which goods and services can be traded anywhere without barriers?

Key Takeaways

- Nations trade because they don’t produce all the products that their inhabitants need.

- The cost of labor, the availability of natural resources, and the level of know-how vary greatly around the world, so not every country has the same resources or is good at producing the same products.

- To explain how countries decide what products to import and export, economists use the concepts of absolute and comparative advantage: A nation has an absolute advantage if it’s the only source of a particular product or can make more of a product with the same amount of or fewer resources than other countries. A comparative advantage exists when a country can produce a product at a lower opportunity cost than other nations.

- We determine a country’s balance of trade by subtracting the value of its imports from the value of its exports. If a country sells more products than it buys, it has a favorable balance, called a trade surplus. If it buys more than it sells, it has an unfavorable balance, or a trade deficit.

- The balance of payments is the difference, over a period of time, between the total flow coming into a country and the total flow going out. The biggest factor in a country’s balance of payments is the money that comes in and goes out as a result of exports and imports.

- A company that operates in many countries is called a multinational corporation (MNC).

- For a company in the United States wishing to expand beyond national borders, there are a variety of ways to get involved in international business:

- Importing involves purchasing products from other countries and reselling them in one’s own.

- Exporting entails selling products to foreign customers.

- Under a franchise agreement, a company grants a foreign company the right to use its brand name and sell its products.

- A licensing agreement allows a foreign company to sell a company’s products or use its intellectual property in exchange for royalty fees.

- Through international contract manufacturing, or outsourcing, a company has its products manufactured or services provided in other countries.

- A joint venture is a type of strategic alliance in which a separate entity funded by the participating companies is formed.

- Foreign direct investment (FDI) refers to the formal establishment of business operations on foreign soil.

- A common form of FDI is the foreign subsidiary, an independent company owned by a foreign firm.

- Success in international business requires an understanding an assortment of cultural, economic, and legal/regulatory differences between countries. Cultural challenges stem from differences in language, concepts of time and sociability, and communication styles.

- Because they protect domestic industries by reducing foreign competition, the use of controls to restrict free trade is often called protectionism.

- Tariffs are taxes on imports. Because they raise the price of the foreign-made goods, they make them less competitive.

- Quotas are restrictions on imports that impose a limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported over a period of time. They’re used to protect specific industries, usually new industries or those facing strong competitive pressure from foreign firms.

- An embargo is a quota that, for economic or political reasons, bans the import or export of certain goods to or from a specific country.

- A common rationale for tariffs and quotas is the need to combat dumping—the practice of selling exported goods below the price that producers would normally charge in their home markets (and often below the costs of producing the goods).

- Free trade is encouraged by a number of agreements and organizations set up to monitor trade policies.

- The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) regulates free trade, reduces tariffs and provides a forum for resolving trade disputes.

- The World Trade Organization (WTO) encourages global commerce and lower trade barriers, enforces international rules of trade, and provides a forum for resolving disputes.

- The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank both provide monetary assistance to the world’s poorest countries.

- In certain parts of the world, groups of countries have formed trading blocs to allow goods and services to flow without restrictions across their mutual borders.

- Examples include the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA) (United States, Canada, and Mexico) and the European Union (EU), a group of 27 countries that have eliminated trade barriers among themselves.

- Globalization is essentially the trend towards increased connections and interdependence in the world’s economies.

Image Credits: Chapter 5

Figure 5.1: Michael Spencer (2009). “Orchard Road, Singapore.” Flickr. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/michaelspencer/4393369407

Figure 5.2: U.S. Census Bureau. “Imports, Exports, and Balance of Payments (1994–2019).” Data retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/historical/goods.pdf

Figure 5.4: Eugene Chystiakov. “Tram in the Budapest.” Unsplash. Public Domain. Retrieved from: https://unsplash.com/photos/qpkKR3N6AJ0

Figure 5.5: Rick Noack (2015). “See How Much (or How Little) You’d Earn If You Did the Same Job in Another Country.” Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/03/03/chart-see-how-much-or-how-little-youd-earn-if-you-did-the-same-job-in-another-country/

Figure 5.6: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. “Where FDI Goes (2000-2018).” Data retrieved from: http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=96740

Figure 5.7: Fortune. “Fortune Top 15 Multinational Firms by Revenue (2019).” Data retrieved from: https://fortune.com/global500/2019/search/

Figure 5.8: Andrea Piacquadio. “Shallow Focus Photo of Man Reading Newspaper.” Pexels. Public Domain. Retrieved from: https://www.pexels.com/photo/shallow-focus-photo-of-man-reading-newspaper-3799099/

Figure 5.9: Transparency International. “Corruption Perceptions Index (2019).” Data retrieved from: http://www.transparency.org/cpi2019

Figure 5.10: Statista. “U.S. Employment by Industry Sector (2019).” Data retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/200143/employment-in-selected-us-industries/

Figure 5.11: Glentamara (2009). “Special Member State Territories In Europe and the European Union.” Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=european union&title=Special:Search&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Special_member_state_territories_in_Europe_and_the_European_Union.svg

- Silk Road Foundation (n.d.). "Marco Polo and His Travels." Silk Road Foundation. Retrieved from: http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/artl/marcopolo.shtml#:~:text=Marco Polo (1254-1324),predecessors, beyond Mongolia to China. ↵

- Liam O'Connell (2019). "Worldwide Export Trade Volume 1950-2018." Statistica. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264682/worldwide-export-volume-in-the-trade-since-1950/ ↵

- Warren E. Buffet and Carol Loomis (2003). “America's Growing Trade Deficit Is Selling The Nation Out From Under Us. Here's A Way To Fix The Problem—And We Need To Do It Now.” Fortune. Retrieved from: http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2003/11/10/352872/index.htm ↵

- Anonymous (2003). “Why Are Prices in Japan So Damn High?” The Japan FAQ.com. Retrieved from: http://www.thejapanfaq.com/FAQ-Prices.html ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau (2015). “U.S. Trade in Goods and Services—Balance of Payments (BOP) Basis, 1960 thru 2014.” Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/historical/gands.txt ↵

- Fine Waters Media (2016). “Bottled Waters of France.” Retrieved from: http://www.finewaters.com/bottled-waters-of-the-world/france/evian; Fiji Water (2016). “Fiji water history.” Retrieved from: https://store.fijiwater.com/about-fiji-water-bottle-delivery ↵

- H. Frederick Gale (2003). “China’s Growing Affluence: How Food Markets Are Responding.” U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2003-june/chinas-growing-affluence.aspx#.Vz-JUfkrIqM ↵

- Wall Street Journal (2019). “Farmers Built a Soybean Export Empire Around China. Now They’re Fighting to Save It.” Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/farmers-built-a-soybean-export-empire-around-china-now-theyre-fighting-to-save-it-11562260248#:~:text=The customer is China and,obscure crop into a blockbuster. ↵

- Gary Gereffi and Stacey Frederick (2010). “The Global Apparel Value Chain, Trade and the Crisis: Challenges and Opportunities for Developing Countries.” World Bank. Retrieved from: http://www19.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2010/05413.pdf ↵

- Paul Lienert and Joyce Lee (2020). "Hyundai Signs Development Deal With Another Electric Wehicle Startup." Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-autos-hyundai-motor-electric-idUSKBN2052MI ↵

- Clothing, Makeup and Beauty Tips (2012). Lihi Griner Cosmopolitan Israel. Retrieved from: http://www.magxone.com/cosmopolitan/lihi-griner-cosmopolitan-israel-may-2012/attachment/lihi-griner-cosmopolitan-israel/; CountryMagazines.Blogspot.com (2015). Retrieved from: http://country-magazines.blogspot.com/2015/09/tennis-maria-sharapova-cosmopolitan.html ↵

- Michael Mandel (2007). “The Real Cost of Offshoring.” Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2007-06-17/the-real-cost-of-offshoring ↵

- James C. Morgan and Jeffrey Morgan (1991). Cracking the Japanese Market. New York: Free Press. p. 102. ↵

- Case Study Inc. (2010). “Glocalization Examples—Think Globally and Act Locally.” CaseStudyInc.com. Retrieved from: http://www.casestudyinc.com/glocalization-examples-think-globally-and-act-locally ↵

- McDonald’s India (n.d.). “McDonald’s India.” Retrieved from: http://www.mcdonaldsindia.com/McDonaldsinIndia.pdf ↵

- Susan L. Nasr (2009). "10 Unusual Items from McDonald's International Menu." HowStuffWorks. Retrieved from: http://money.howstuffworks.com/10-items-from-mcdonalds-international-menu5.htm ↵

- James C. Morgan and J. Jeffrey Morgan (1991). Cracking the Japanese Market. New York: Free Press. p. 117. ↵

- Anne O. Krueger (2002). “Supporting Globalization.” Eisenhower National Security Conference: “National Security for the 21st Century: Anticipating Challenges, Seizing Opportunities, Building Capabilities.” Retrieved from: http://www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/2002/092602a.htm ↵

- World Bank Group (2016). “Country and Lending Groups.” Retrieved from: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups ↵

- David Ricks (1999). Blunders in International Business. Malden, MA: Blackwell. p. 137. ↵

- Transparency.org (2016). “What is Corruption?” Retrieved from: http://www.transparency.org/ ↵

- International Trade Administration, Industry and Analysis, National Travel and Tourism Office (2015). “Fast Facts: United States Travel and Tourism Industry 2014.” Retrieved from: http://travel.trade.gov/outreachpages/download_data_table/Fast_Facts_2014.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015). “Employment Projections: Employment by Major Industry Sector.” Retrieved from: http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_201.htm ↵

- International Trade Administration, Industry and Analysis, National Travel and Tourism Office (2015). “Fast Facts: United States Travel and Tourism Industry 2014.” Retrieved from: http://travel.trade.gov/outreachpages/download_data_table/Fast_Facts_2014.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration (2015). “U.S. Commerce Department Releases Six-Year Forecast for International Travel to the United States: 2015-2020.” Retrieved from: http://travel.trade.gov/view/f-2000-99-001/forecast/Forecast_Summary.pdf ↵

- Daniel Griswold (2009). “The Protectionist Swindle: How Trade Barriers Cheat the Poor and Middle Class.” Insider Online. Retrieved from: http://www.insideronline.org/2009/12/the-protectionist-swindle-how-trade-barriers-cheat-the-poor-and-middle-class/ ↵

- Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America (2015). “Tariff Reduction Initiatives.” Retrieved from: http://fdra.org/key-issues-and-advocacy/legislative-initiatives/ ↵

- Chris Edwards (2007). “The Sugar Racket.” CATO Institute Tax and Budget Bulletin. Retrieved from: http://www.cato.org/pubs/tbb/tbb_0607_46.pdf ↵

- James Pritchard (2002). “Sole U.S. Life Savers plant closing, moving to Canada.” Southeast Missourian. Retrieved from: http://www.semissourian.com/story/70976.html ↵

- Philip Blenkinsop (2020). "EU is 'very concerned' by delayed WTO decision on tariffs vs US." Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-eu/eu-is-very-concerned-by-delayed-wto-decision-on-tariffs-vs-u-s-idUSKBN23W2L7 ↵

- 1 Bernard Sanders (1998). “The International Monetary Fund Is Hurting You.” Z Magazine. Retrieved from: http://www.thirdworldtraveler.com/IMF_WB/IMF_Sanders.html ↵

- World Bank (2016). "Fiscal Year Data 2011-15." Retrieved from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/about/annual-report/fiscalyeardata#1 ↵

- USMCA (2019). "Agreement between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada." Office of the United States Trade Representative. Retrieved from: https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement-between ↵

- European Commission on Economic, and Financial Affairs (2015). “Why the Euro?” Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/euro/why/index_en.htm ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Paul Krugman (2011). “The Economic Failure of the Euro.” National Public Radio. Retrieved from: http://www.npr.org/2011/01/25/133112932/paul-krugman-the-economic-failure-of-the-euro ↵

- Willem Buiter (2010). “Three Steps to Survival for Euro Zone.” Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703766704576009423447485768.html ↵