Chapter 14 Marketing: Providing Value to Customers

Learning Objectives

- Define the terms marketing, marketing concept, and marketing strategy.

- Outline the tasks involved in selecting a target market.

- Identify the four Ps of the marketing mix.

- Explain how to conduct marketing research.

- Discuss various branding strategies and explain the benefits of packaging and labeling.

- Describe the elements of the promotion mix.

- Explain how companies manage customer relationships.

- Identify the advantages and disadvantages of social media marketing.

A Robot with Attitude

Mark Tilden used to build robots for NASA that ended up being destroyed on Mars, but after seven years of watching the results of his work meet violent ends 36 million miles from home, he decided to specialize in robots for earthlings. He left the space world for the toy world and teamed up with Wow Wee Toys Ltd. to create “Robosapien,” an intelligent robot with an attitude.[1] The 14-inch-tall robot, which is operated by remote control, has great moves. In addition to walking forward, backward, and turning, he dances, raps, and gives karate chops. He can pick up small objects and even fling them across the room, and he does everything while grunting, belching, and emitting other “bodily” sounds.

Robosapien gave Wow Wee Toys a good head start in the toy robot market: in the first five months, more than 1.5 million Robosapiens were sold.[2] The company expanded the line to more than a dozen robotics and other interactive toys, including FlyTech Bladestar, a revolutionary indoor flying machine that won a Popular Mechanics magazine Editor’s Choice Award in 2008).[3]

What does Robosapien have to do with marketing? The answer is fairly simple: though Mark Tilden is an accomplished inventor who has created a clever product, Robosapien wouldn’t be going anywhere without the marketing expertise of Wow Wee. In this chapter, we’ll look at the ways in which marketing converts product ideas like Robosapien into commercial successes.

What Is Marketing?

When you consider the functional areas of business—accounting, finance, management, marketing, and operations—marketing is the one you probably know the most about. After all, as a consumer and target of all sorts of advertising messages, you’ve been on the receiving end of marketing initiatives for most of your life. What you probably don’t appreciate, however, is the extent to which marketing focuses on providing value to the customer. According to the American Marketing Association, “Marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.”[4]

In other words, marketing isn’t just advertising and selling. It includes everything that organizations do to satisfy customer needs:

- Coming up with a product and defining its features and benefits.

- Setting its price.

- Identifying its target market.

- Making potential customers aware of it.

- Getting people to buy it.

- Delivering it to people who buy it.

- Managing relationships with customers after it has been delivered.

Think about a typical business—a local movie theater, for example. It’s easy to see how the person who decides what movies to show is involved in marketing: he or she selects the product to be sold. It’s even easier to see how the person who puts ads in the newspaper works in marketing: he or she is in charge of advertising—making people aware of the product and getting them to buy it. What about the ticket seller and the person behind the counter who gets the popcorn and soda or the projectionist? Are they marketing the business? Absolutely. The purpose of every job in the theater is satisfying customer needs, and as we’ve seen, identifying and satisfying customer needs is what marketing is all about. Marketing is a team effort involving everyone in the organization.

If everyone is responsible for marketing, can the average organization do without an official marketing department? Not necessarily: most organizations have marketing departments in which individuals are actively involved in some marketing-related activity—product design and development, pricing, promotion, sales, and distribution. As specialists in identifying and satisfying customer needs, members of the marketing department manage—plan, organize, lead, and control—the organization’s overall marketing efforts.

The Marketing Concept

Figure 14.2 is designed to remind you that to achieve company profitability goals, you need to start with three things:

- Find out what customers or potential customers need.

- Develop products to meet those needs.

- Engage the entire organization in efforts to satisfy customers.

At the same time, you need to achieve organizational goals, such as profitability and growth. This basic philosophy—satisfying customer needs while meeting organizational goals—is called the marketing concept, and when it’s effectively applied, it guides all of an organization’s marketing activities.

The marketing concept puts the customer first: as your most important goal, satisfying the customer must be the goal of everyone in the organization. But this doesn’t mean that you ignore the bottom line; if you want to survive and grow, you need to make some profit. What you’re looking for is the proper balance between the commitments to customer satisfaction and company survival. Consider the case of Medtronic, a manufacturer of medical devices, such as pacemakers and defibrillators. The company boasts more than 50 percent of the market in cardiac devices and is considered the industry standard setter.[5] Everyone in the organization understands that defects are intolerable in products that are designed to keep people alive. Thus, committing employees to the goal of zero defects is vital to both Medtronic’s customer base and its bottom line. “A single quality issue,” explains CEO Arthur D. Collins Jr., “can deep-six a business.”[6]

Selecting a Target Market

Businesses earn profits by selling goods or providing services. It would be nice if everybody in the marketplace was interested in your product, but if you tried to sell it to everybody, you’d probably spread your resources too thin. You need to identify a specific group of consumers who should be particularly interested in your product, who would have access to it, and who have the means to buy it. This group represents your target market, and you need to aim your marketing efforts at its members.

Identifying Your Market

How do marketers identify target markets? First, they usually identify the overall market for their product—the individuals or organizations that need a product and are able to buy it. This market can include either or both of two groups:

- A consumer market—buyers who want the product for personal use

- An industrial market—buyers who want the product for use in making other products

You might focus on only one market or both. A farmer, for example, might sell blueberries to individuals on the consumer market and, on the industrial market, to bakeries that will use them to make muffins and pies.

Segmenting the Market

The next step in identifying a target market is to divide the entire market into smaller portions, or market segments—groups of potential customers with common characteristics that influence their buying decisions. An especially narrow market segment is known as a niche market, for example, extreme luxury goods that less than 1 percent of people can afford. Let’s look at some of the most useful categories in detail.

Demographic segmentation

Demographic segmentation divides the market into groups based on such variables as age, marital status, gender, ethnic background, income, occupation, and education.

Age, for example, will be of interest to marketers who develop products for children, retailers who cater to teenagers, colleges that recruit students, and assisted-living facilities that promote services among the elderly. Lifetime Television for Women targets female viewers, while Telemundo networks targets Hispanics. When Hyundai offers recent college graduates a $400 bonus towards leasing or buying a new Hyundai, the company’s marketers are segmenting the market according to education level.[7]

Geographic segmentation

Geographic segmentation—dividing a market according to such variables as climate, region, and population density (urban, suburban, small-town, or rural)—is also quite common. Climate is crucial for many products: snow shovels would not sell in Hawaii. Consumer tastes also vary by region. That’s why McDonald’s caters to regional preferences, offering a breakfast of Spam and rice in Hawaii, [8] tacos in Arizona, and lobster rolls in Massachusetts.[9] Outside the United States, menus diverge even more widely (you can get seaweed burgers or, if you prefer, seasoned seaweed fries in Japan).[10]

Likewise, differences between urban and suburban life can influence product selection. For example, it’s a hassle to parallel park on crowded city streets. Thus, Toyota engineers have developed a product especially for city dwellers. The Japanese version of the Prius, Toyota’s hybrid gas-electric car, can automatically parallel park itself. Using computer software and a rear-mounted camera, the parking system measures the spot, turns the steering wheel, and swings the car into the space (making the driver—who just sits there—look like a master of parking skills).[11] After its success in the Japanese market, the self-parking feature was brought to the United States.

Behavioral segmentation

Dividing consumers by such variables as attitude toward the product, user status, or usage rate is called behavioral segmentation. Companies selling technology-based products might segment the market according to different levels of receptiveness to technology. They could rely on a segmentation scale developed by Forrester Research that divides consumers into two camps: technology optimists, who embrace new technology, and technology pessimists, who are indifferent, anxious, or downright hostile when it comes to technology.[12]

Some companies segment consumers according to user status, distinguishing among nonusers, potential users, first-time users, and regular users of a product. Depending on the product, they can then target specific groups, such as first-time users. Credit-card companies use this approach when they offer membership points to potential customers in order to induce them to get their card.

Psychographic segmentation

Psychographic segmentation classifies consumers on the basis of individual lifestyles as they’re reflected in people’s interests, activities, attitudes, and values. Do you live an active life and love the outdoors? If so, you may be a potential buyer of hiking or camping equipment or apparel. If you’re a risk taker, you might catch the attention of a gambling casino. The possibilities are limited only by the imagination.

Clustering Segments

Typically, marketers determine target markets by combining, or “clustering,” segmenting criteria. What characteristics does Starbucks look for in marketing its products? Three demographic variables come to mind: age, geography, and income. Buyers are likely to be males and females ranging in age from about 25 to 40 (although college students, aged 18 to 24, are moving up in importance). Geography is a factor as customers tend to live or work in cities or upscale suburban areas. Those with relatively high incomes are willing to pay a premium for Starbucks specialty coffee and so income—a socioeconomic factor—is also important.

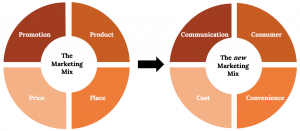

The Marketing Mix

After identifying a target market, your next step is developing and implementing a marketing program designed to reach it. As Figure 14.4 shows, this program involves a combination of tools called the marketing mix, often referred to as the “four Ps” of marketing:

- Developing a product that meets the needs of the target market

- Setting a price for the product

- Distributing the product—getting it to a place where customers can buy it

- Promoting the product—informing potential buyers about it

Pricing will be covered in more detail in its own dedicated chapter.

Developing a Product

The development of Robosapien was a bit unusual for a company that was already active in its market.[13] Generally, product ideas come from people within the company who understand its customers’ needs. Internal engineers are then challenged to design the product. In the case of Robosapien, the creator, Mark Tilden, had conceived and designed the product before joining Wow Wee Toys. The company gave him the opportunity to develop the product for commercial purposes, and Tilden was brought on board to oversee the development of Robosapien into a product that satisfied Wow Wee’s commercial needs.

Robosapien is not a “kid’s toy,” though kids certainly love its playful personality. It’s a home-entertainment product that appeals to a broad audience—children, young adults, older adults, and even the elderly. It’s a big gift item, and it has developed a following of techies and hackers who take it apart, tinker with it, and even retrofit it with such features as cameras and ice skates.

Conducting Marketing Research

Before settling on a strategy for Robosapien, the marketers at Wow Wee did some homework. First, to zero in on their target market, they had to find out what various people thought of the product. More precisely, they needed answers to questions like the following:

- Who are our potential customers?

- What do they like about Robosapien? What would they change?

- How much are they willing to pay for it?

- Where will they expect to buy it?

- How can we distinguish it from competing products?

- Will enough people buy Robosapien to return a reasonable profit for the company?

The last question would be left up to Wow Wee management, but, given the size of the investment needed to bring Robosapien to market, Wow Wee couldn’t afford to make the wrong decision. Ultimately, the company was able to make an informed decision because its marketing team provided answers to key questions through marketing research—the process of collecting and analyzing the data that are relevant to a specific marketing situation. This data had to be collected in a systematic way. Market research seeks two types of data:

- Marketers generally begin by looking at secondary data—information already collected, whether by the company or by others, that pertains to the target market.

- With secondary data in hand, they’re prepared to collect primary data—newly collected information that addresses specific questions.

Secondary data can come from inside or outside the organization. Internally available data includes sales reports and other information on customers. External data can come from a number of sources. The US Census Bureau, for example, posts demographic information on American households (such as age, income, education, and number of members), both for the country as a whole and for specific geographic areas.

Population data helped Wow Wee estimate the size of its potential US target market. Other secondary data helped the firm assess the size of foreign markets in regions around the world, such as Europe, the Middle East, Latin America, Asia, and the Pacific Rim. This data helped position the company to sell Robosapien in 85 countries, including Canada, England, France, Germany, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Japan.

Using secondary data that is already available (and free) is a lot easier than collecting your own information. Unfortunately, however, secondary data didn’t answer all the questions that Wow Wee was asking in this particular situation. To get these answers, the marketing team had to conduct primary research, working directly with members of their target market. First they had to decide exactly what they needed to know, then determine who to ask and what methods would be most effective in gathering the information.

We know what they wanted to know—we’ve already listed example questions. As for whom to talk to, they randomly selected representatives from their target market. There is a variety of tools for collecting information from these people, each of which has its advantages and disadvantages. To understand the marketing-research process fully, we need to describe the most common of these tools:

- Surveys. Sometimes marketers mail questionnaires to members of the target market. The process is time consuming and the response rate generally low. Online surveys are easier to answer and so get better response rates than other approaches.

- Personal interviews. Though time consuming, personal interviews not only let you talk with real people but also let you demonstrate the product. You can also clarify answers and ask open-ended questions.

- Focus groups. With a focus group, you can bring together a group of individuals (perhaps 6 to 10) and ask them questions. A trained moderator can explain the purpose of the group and lead the discussion. If sessions are run effectively, you can come away with valuable information about customer responses to both your product and your marketing strategy.

Wow Wee used focus groups and personal interviews because both approaches had the advantage of allowing people to interact with Robosapien. In particular, focus-group sessions provided valuable opinions about the product, proposed pricing, distribution methods, and promotion strategies.

Researching your target market is necessary before you launch a new product, but the benefits of marketing research don’t extend merely to brand-new products. Companies also use it when they’re deciding whether or not to refine an existing product or develop a new marketing strategy for an existing product. Kellogg’s, for example, conducted online surveys to get responses to a variation on its Pop-Tarts brand—namely, Pop-Tarts filled with a mixture of traditional fruit filling and yogurt. Marketers had picked out four possible names for the product and wanted to know which one kids and mothers liked best. They also wanted to know what they thought of the product and its packaging. Both mothers and kids liked the new Pop-Tarts (though for different reasons) and its packaging, and the winning name for the product launched in the spring of 2011 was “Pop-Tarts Yogurt Blasts.” The online survey of 175 mothers and their children was conducted in one weekend by an outside marketing research group.[14]

Branding

Armed with positive feedback from their research efforts, the Wow Wee team was ready for the next step: informing buyers—both consumers and retailers—about their product. They needed a brand—some word, letter, sound, or symbol that would differentiate their product from similar products on the market. They chose the brand name Robosapien, hoping that people would get the connection between homo sapiens (the human species) and Robosapien (the company’s coinage for its new robot “species”). To prevent other companies from coming out with their own “Robosapiens,” they took out a trademark: a symbol, word, or words legally registered or established by use as representing a company or product. Trademarking requires registering the name with the US Patent and Trademark Office. Though this approach—giving a unique brand name to a particular product—is a bit unusual, it isn’t unprecedented. Mattel, for example, established a separate brand for Barbie, and Anheuser–Busch sells beer under the brand name Budweiser. Note, however, that the more common approach, which is taken by such companies as Microsoft, Dell, and Apple, calls for marketing all the products made by a company under the company’s brand name.

Branding Strategies

Companies can adopt one of three major strategies for branding a product:

- With private branding (or private labeling), a company makes a product and sells it to a retailer who in turn resells it under its own name. A soft-drink maker, for example, might make cola for Wal-Mart to sell as its Sam’s Choice Cola.

- With generic branding, the maker attaches no branding information to a product except a description of its contents. Customers are often given a choice between a brand-name prescription drug or a cheaper generic drug with the same formula.

- With manufacturer branding, a company sells one or more products under its own brand names. Adopting a multiproduct-branding approach, it sells many products under one brand name. Food-maker ConAgra sells soups, frozen treats, and complete meals under its Healthy Choice label. Using a multibranding approach, the company assigns different brand names to products covering different segments of the market. Automakers often use multibranding. The Volkswagen group of brands also includes Audi and Lamborghini.

Branding is used in hotels to allow chains (Marriott, Hyatt, Hilton) to offer hotel brands that meet various customers’ travel needs while still maintaining their loyalty to the chain. The same customer who would choose an Extended Stay hotel with a full kitchen when on a long term assignment might stay at a convention hotel when attending a trade show and then stay in a resort property when traveling with their family. By segmenting different types of hotel locations, amenities, room sizes and décor, hotel chains can meet the needs of a wide variety of travelers. In the past decade “soft” branding has become common to allow unique hotels to take advantage of being part of a chain reservation system and loyalty program. For example, Marriott has over 100 affiliated independent hotels in its Autograph Collection.[15]

| Type of Hotel | Mariott | Hilton | Hyatt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luxury | Ritz Carlton

JW Marriott |

Waldorf Astoria

Conrad |

Park Hyatt

Andaz |

| Independent | Autograph Collection | Curio Collection | Unbound Collection |

| Full Service | Marriott

Renaissance Gaylord |

Hilton

Canopy Doubletree |

Hyatt |

| Select Service | Courtyard by Marriott

AC Hotels |

Hilton Garden Inn

Hampton Inn |

Hyatt Place |

| Extended Stay | Residence Inn | Homewood Suites | Hyatt House |

Loyalty programs are heavily used in the hospitality industry, especially airlines and hotels, as part of their Customer Relationship Management programs. Loyalty programs are often targeted to high value business travelers with less price sensitivity. They achieve loyalty status and perks while traveling as well as earning points to use for personal travel rewards. Once a loyalty program member obtains elite status with significant associated perks such as guaranteed room availability, airport club lounge access, etc., the customer is much less likely to use other brands.

Building Brand Equity

Wow Wee went with the multibranding approach, deciding to market Robosapien under the robot’s own brand name. Was this a good choice? The answer would depend, at least in part, on how well the product sells. Another consideration is the impact on Wow Wee’s other brands. If Robosapien fared poorly, its failure would not reflect badly on Wow Wee’s other products. On the other hand, if customers liked Robosapien, they would have no reason to associate it with other Wow Wee products. In this case, Wow Wee wouldn’t gain much from its brand equity—any added value generated by favorable consumer experiences with Robosapien. To get a better idea of how valuable brand equity is, think for a moment about the effect of the name Dell on a product. When you have a positive experience with a Dell product—say, a laptop or a printer—you come away with a positive opinion of the entire Dell product line and will probably buy more Dell products. Over time, you may even develop brand loyalty: you may prefer—or even insist on—Dell products. Not surprisingly, brand loyalty can be extremely valuable to a company. Because of customer loyalty, Apple’s brand tops Interbrand’s Best Global Brands ranking with a value of over $170 billion. Google’s brand is valued at $120 billion, the Coca-Cola brand is estimated at more than $78 billion, and Microsoft and IBM round out the top five, with brands valued at over $65 billion each.[16]

Packaging and Labeling

Packaging can influence a consumer’s decision to buy a product or pass it up. Packaging gives customers a glimpse of the product, and it should be designed to attract their attention, with consideration given to color choice, style of lettering, and many other details. Labeling not only identifies the product but also provides information on the package contents: who made it and where or what risks are associated with it (such as being unsuitable for small children).

How has Wow Wee handled the packaging and labeling of Robosapien? The robot is 14 inches tall, and is also fairly heavy (about seven pounds), and because it’s made out of plastic and has movable parts, it’s breakable. The easiest, and least expensive, way of packaging it would be to put it in a square box of heavy cardboard and pad it with Styrofoam. This arrangement would not only protect the product from damage during shipping but also make the package easy to store. However, it would also eliminate any customer contact with the product inside the box (such as seeing what it looks like). Wow Wee, therefore, packages Robosapien in a container that is curved to his shape and has a clear plastic front that allows people to see the whole robot. Why did Wow Wee go to this much trouble and expense? Like so many makers of so many products, it has to market the product while it’s still in the box.

Meanwhile, the labeling on the package details some of the robot’s attributes. The name is highlighted in big letters above the descriptive tagline “A fusion of technology and personality.” On the sides and back of the package are pictures of the robot in action with such captions as “Dynamic Robotics with Attitude” and “Awesome Sounds, Robo-Speech & Lights.” These colorful descriptions are conceived to entice the consumer to make a purchase because its product features will satisfy some need or want.

Packaging can serve many purposes. The Robosapien package attracts attention to the product’s features. For other products, packaging serves a more functional purpose. Nabisco packages some of its snacks—Oreos, Chips Ahoy, and Lorna Doone’s—in “100 Calorie Packs.” The packaging makes life simpler for people who are keeping track of calories.

Place

A great deal is involved in getting a product to the place in which it is ultimately sold. If you’re a fast food retailer, for example, you’ll want your restaurants to be in high-traffic areas to maximize your potential business. If your business is selling beer, you’ll want it to be offered in bars, restaurants, grocery stores, convenience stores, and even stadiums. Placing a product in each of these locations requires substantial negotiations with the owners of the space, and often the payment of slotting fees, an allowance paid by the manufacturer to secure space on store shelves.

Retailers are marketing intermediaries that sell products to the eventual consumer. Without retailers, companies would have a much more difficult time selling directly to individual consumers, no doubt at a substantially higher cost. The most common types of retailers are summarized in Figure 14.7 below. You will likely recognize many of the examples provided. It is important to note that many retailers do not fit neatly into only one category. For example, WalMart, which began as a discount store, has added groceries to many of its outlets, also placing it in competition with supermarkets.

| Type of Retailer | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Category Killer | Sells a wide variety of products of a particular type, selling at a low price due to their large scale | Dick’s Sporting Goods |

| Convenience Store | Offers food, beverages, and other products, typically in individual servings, at a higher price, and geared to fast service | 7-Eleven |

| Department Store | Offers a wide assortment of products grouped into different departments (e.g., jewelry, apparel, perfume) | Nordstrom, Macy’s |

| Discount Store | Organized into departments, but offer a range of merchandise generally seen as lower quality and at a much lower price | Target, Wal Mart |

| Specialty Store | Offers goods typically confined to a narrow category; high level of personal service and higher prices than other retailers | Local running shops or jewelry stores |

| Supermarket | Offers mostly consumer staples such as food and other household items | Kroger, Food Lion |

| Warehouse Club Stores | Offers a wide variety of products in a warehouse-style setting; sells many products in bulk; usually requires membership fee | Costco, Sam’s Club |

Of course, in an age where e-commerce is taking an increasing share of the retail spending dollar, “place” is not always a physical location that the customer visits. Products ordered online ship from manufacturers to distribution centers and then directly on to the end customer without passing through a traditional retail outlet. An emerging trend in retailing is showrooming in which a customer visits a traditional retailer, gets familiar with particular items available, and then orders the item online, often from an unrelated online retailer. The term comes from the fact that the traditional retail outlet has served only as a showroom—a place to view the product, as opposed to a place where the sale is made. As shopping habits change, retailers have been challenged to keep their space relevant and attractive to the ultimate consumer.

Promoting a Product

Your promotion mix—the means by which you communicate with customers—may include advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, and publicity. These are all tools for telling people about your product and persuading potential customers to buy it. Before deciding on an appropriate promotional strategy, you should consider a few questions:

- What’s the main purpose of the promotion?

- What is my target market?

- Which product features should I emphasize?

- How much can I afford to invest in a promotion campaign?

- How do my competitors promote their products?

To promote a product, you need to imprint a clear image of it in the minds of your target audience. What do you think of, for instance, when you hear “Ritz-Carlton”? What about “Motel 6”? They’re both hotel chains, that have been quite successful in the hospitality industry, but they project very different images to appeal to different clienteles. The differences are evident in their promotions. The Ritz-Carlton web site describes “luxury hotels” and promises that the chain provides “the finest personal service and facilities throughout the world.”[17] Motel 6, by contrast, characterizes its facilities as “discount hotels” and assures you that you’ll pay “the lowest price of any national chain.”[18]

Promotional Tools

We’ll now examine each of the elements that can go into the promotion mix—advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, and publicity. Then we’ll see how Wow Wee incorporated them into a promotion mix to create a demand for Robosapien.

Advertising

Advertising is paid, non-personal communication designed to create an awareness of a product or company. Ads are everywhere—in print media (such as newspapers, magazines, the Yellow Pages), on billboards, in broadcast media (radio and TV), and on the Internet. It’s hard to escape the constant barrage of advertising messages; it’s estimated that the average consumer is confronted by about 5,000 ad messages each day (compared with about 500 ads a day in the 1970s).[19] For this very reason, ironically, ads aren’t as effective as they used to be. Because we’ve learned to tune them out, companies now have to come up with innovative ways to get through to potential customers. A New York Times article[20] claims that “anywhere the eye can see, it’s likely to see an ad.” Subway turnstiles are plastered with ads for GEICO auto insurance, Chinese food containers are decorated with ads for Continental Airways, and parking meters display ads for Campbell’s Soup[21] Advertising is still the most prevalent form of promotion.

The choice of advertising media depends on your product, target audience, and budget. A popular vacation destination selling spring-break getaways to college students might post flyers on campus bulletin boards or run ads on social media platforms. The co-founders of Nantucket Nectars found radio ads particularly effective. Rather than pay professionals, they produced their own ads themselves.[22] As unprofessional as this might sound, the ads worked, and the business grew.

Personal Selling

Personal selling refers to one-on-one communication with customers or potential customers. This type of interaction is necessary in selling large-ticket items, such as homes, and it’s also effective in situations in which personal attention helps to close a sale, such as sales of cars and insurance policies.

Many retail stores depend on the expertise and enthusiasm of their salespeople to persuade customers to buy. Home Depot has grown into a home-goods giant in large part because it fosters one-on-one interactions between salespeople and customers. The real difference between Home Depot and everyone else isn’t the merchandise; it’s the friendly, easy-to-understand advice that sales people give to novice homeowners, according to one of its cofounders.[23] Best Buy’s knowledgeable sales associates make them “uniquely positioned to help consumers navigate the increasing complexity of today’s technological landscape,” according to CEO Hubert Joly.[24]

Sales Promotion

It’s likely that at some point, you have purchased an item with a coupon or because it was advertised as a buy-one-get-one special. If so, you have responded to a sales promotion—one of the many ways that sellers provide incentives for customers to buy. Sales promotion activities include not only those mentioned above but also other forms of discounting, sampling, trade shows, in-store displays, and even sweepstakes. Some promotional activities are targeted directly to consumers and are designed to motivate them to purchase now. You’ve probably heard advertisers make statements like “limited time only” or “while supplies last.” If so, you’ve encountered a sales promotion directed at consumers. Other forms of sales promotion are directed at dealers and intermediaries. Trade shows are one example of a dealer-focused promotion. Mammoth centers such as McCormick Place in Chicago host enormous events in which manufacturers can display their new products to retailers and other interested parties. At food shows, for example, potential buyers can sample products that manufacturers hope to launch to the market. Feedback from prospective buyers can even result in changes to new product formulations or decisions not to launch.

Publicity and Public Relations

Free publicity—say, getting your company or your product mentioned or pictured in a newspaper or on TV—can often generate more customer interest than a costly ad. When Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine were finalizing the development of their Beats headphones, they sent a pair to LeBron James. He liked them so much he asked for 15 more pairs, and they “turned up on the ears of every member of the 2008 US Olympic basketball team when they arrived in Shanghai. ‘Now that’s marketing,’ says Iovine.”[25] It wasn’t long before the pricey headphones became a must-have fashion accessory for everyone from celebrities to high school students.

Consumer perception of a company is often important to a company’s success. Many companies, therefore, manage their public relations in an effort to garner favorable publicity for themselves and their products. When the company does something noteworthy, such as sponsoring a fundraising event, the public relations department may issue a press release to promote the event. When the company does something negative, such as selling a prescription drug that has unexpected side effects, the public relations department will work to control the damage to the company. Each year the Hay Group and Korn Ferry survey more than 1,000 company top executives, directors, and industry leaders in twenty countries to identify companies that have exhibited exceptional integrity or commitment to corporate social responsibility. The rankings are publishes annually as Fortune magazine’s “World’s Most Admired Companies.®”[26] Topping the list in 2016 are Apple, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and Walt Disney.[27]

Marketing Robosapien

Now let’s look more closely at the strategy that Wow Wee pursued in marketing Robosapien in the United States. The company’s goal was ambitious: to promote the robot as a must-have item for kids of all ages. As we know, Wow Wee intended to position Robosapien as a home-entertainment product, not as a toy. The company rolled out the product at Best Buy, which sells consumer electronics, computers, entertainment software, and appliances. As marketers had hoped, the robot caught the attention of consumers shopping for TV sets, DVD players, home and car audio equipment, music, movies, and games. Its $99 price tag was a little lower than the prices of other merchandise, and that fact was an important asset: shoppers were willing to treat Robosapien as an impulse item—something extra to pick up as a gift or as a special present for children, as long as the price wasn’t too high.

Meanwhile, Robosapien was also getting lots of free publicity. Stories appeared in newspapers and magazines around the world, including the New York Times, the Times of London, Time magazine, and National Parenting magazine. Commentators on The Today Show, The Early Show, CNN, ABC News, and FOX News all covered it. The product received numerous awards, and experts predicted that it would be a hot item for the holidays.

At Wow Wee, Marketing Director Amy Weltman (who had already had a big hit with the Rubik’s Cube) developed a gala New York event to showcase the product. From mid- to late August, actors dressed in six-foot robot costumes roamed the streets of Manhattan, while the 14-inch version of Robosapien performed in venues ranging from Grand Central Station to city bars. Everything was recorded, and film clips were sent to TV stations.

The stage was set for expansion into other stores. Macy’s ran special promotions, floating a 24-foot cold-air robot balloon from its rooftop and lining its windows with armies of Robosapien’s. Wow Wee trained salespeople to operate the product so that they could help customers during in-store demonstrations. Other retailers, including The Sharper Image, Spencer’s, and Toys “R” Us, carried Robosapien, as did e-retailers such as Amazon.com. The product was also rolled out (with the same marketing flair) in Europe and Asia.

When national advertising hit in September, all the pieces of the marketing campaign came together—publicity, sales promotion, personal selling, and advertising. Wow Wee ramped up production to meet anticipated fourth-quarter demand and waited to see whether Robosapien would live up to commercial expectations.

Interacting with Customers

Customer-Relationship Management

Customers are the most important asset that any business has. Without enough good customers, no company can survive. Firms must not only attract new customers but also retain current customers. In fact, repeat customers are more profitable. It’s estimated that it costs as much as five times more to attract and sell to a new customer than to an existing one.[28] Repeat customers also tend to spend more, and they’re much more likely to recommend you to other people.

Retaining customers is the purpose of customer-relationship management—a marketing strategy that focuses on using information about current customers to nurture and maintain strong relationships with them. The underlying theory is fairly basic: to keep customers happy, you treat them well, give them what they want, listen to them, reward them with discounts and other loyalty incentives, and deal effectively with their complaints.

Take Caesars Entertainment Corporation, which operates more than 50 casinos under several brands, including Caesars, Harrah’s, Bally’s, and Horseshoe. Each year, it sponsors the World Series of Poker with a top prize in the millions. Caesars gains some brand recognition when the 22-hour event is televised on ESPN, but the real benefit derives from the information cards filled out by the 7,000 entrants who put up $10,000 each. Data from these cards is fed into Caesars database, and almost immediately every entrant starts getting special attention, including party invitations, free entertainment tickets, and room discounts. The program is all part of Harrah’s strategy for targeting serious gamers and recognizing them as its best customers.[29]

Sheraton Hotels uses a softer approach to entice return customers. Sensing that its resorts needed both a new look and a new strategy for attracting repeat customers, Sheraton launched its “Year of the Bed” campaign; in addition to replacing all its old beds with luxurious new mattresses and coverings, it issued a “service promise guarantee”—a policy that any guest who’s dissatisfied with his or her Sheraton stay will be compensated. The program also calls for a customer-satisfaction survey and discount offers, both designed to keep the hotel chain in touch with its customers.[30]

Another advantage of keeping in touch with customers is the opportunity to offer them additional products. Amazon.com is a master at this strategy. When you make your first purchase at Amazon.com, you’re also making a lifelong “friend”—one who will suggest (based on what you’ve bought before) other things that you might like to buy. Because Amazon.com continually updates its data on your preferences, the company gets better at making suggestions.

Social Media Marketing

In the last several years, the popularity of social media marketing has exploded. You already know what social media is—Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, and any number of other online sites that allow you to network, share your opinions, ideas, photos, etc. Social media marketing is the practice of including social media as part of a company’s marketing program.

Why do businesses use social media marketing? Before responding, ask yourself these questions: how much time do I spend watching TV? When I watch TV, do I sit through the ads? Do I read newspapers or magazines and flip right past the ads? Now, put yourself in the place of Annie Young-Scrivner, global chief marketing officer of Starbucks. Does it make sense for her to spend millions of dollars to place an ad for Starbucks on TV or in a newspaper or magazine? Or should she instead spend the money on social media marketing initiatives that have a high probability of connecting to Starbucks’s market?

For companies like Starbucks, the answer is clear. The days of trying to reach customers through ads on TV, in newspapers, or in magazines are over. Most television watchers skip over commercials, and few Starbucks’s customers read newspapers or magazines, and even if they do, they don’t focus on the ads. Social media marketing provides a number of advantages to companies, including enabling them to[31]

- create brand awareness;

- connect with customers and potential customers by engaging them in two-way communication;

- build brand loyalty by providing opportunities for a targeted audience to participate in company-sponsored activities, such as contests;

- offer and publicize incentives, such as special discounts or coupons;

- gather feedback and ideas on how to improve products and marketing initiatives;

- allow customers to interact with each other and spread the word about a company’s products or marketing initiatives; and

- take advantage of low-cost marketing opportunities by being active on free social sites, such as Facebook.

To get an idea of the power of social media marketing, think of the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. According to the ALS Association: “the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge started in the summer of 2014 and became the world’s largest global social media phenomenon. More than 17 million people uploaded their challenge videos to Facebook; these videos were watched by 440 million people a total of 10 billion times.”[32] The ALS Association raised $115 million in six weeks (their usual annual budget was only $20 million).[33] To see how companies try to harness this power, let’s look at social media campaigns of two leaders in this field: PepsiCo (Mountain Dew) and Starbucks.

Mountain Dew (PepsiCo)

When PepsiCo announced it wouldn’t show a television commercial during the 2010 Super Bowl game, it came as a surprise (probably a pleasant one to its competitor, Coca-Cola, who had already signed on to show several Super Bowl commercials). What PepsiCo planned to do instead was invest $20 million into social media marketing campaigns. One of PepsiCo’s most successful social media initiatives has been the DEWmocracy campaign, which two years earlier, resulted in the launch of product—Voltage—created by Mountain Dew fans.[34] Now called DEWcision, the 2016 campaign asks fans to vote between two rival flavors of Mountain Dew. The campaign engages a number of social media outlets with challenges for fans to earn votes for their favorite flavor, including Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.[35] The example in Figure 14.14 is for a challenge to dye your hair the color of your favorite flavor, then Tweet the picture with the hashtag #DewDye. According to Mountain Dew’s director of marketing, “PepsiCo looks at social media as the best way to get direct dialog with their fans and for the company to hear from those fans without filters. ‘It’s been great for us to have this really unique dialogue that we normally wouldn’t have,’ he said. ‘It really has opened our eyes up.’”[36]

Starbucks

One of most enthusiastic users of social media marketing is Starbucks. Let’s look at a few of their promotions: a discount for “Foursquare” mayors and free coffee on Tax Day via Twitter’s promoted tweets and a free pastry day promoted through Twitter and Facebook.[37]

Discount for “Foursquare” Mayors of Starbucks

This promotion was a joint effort of Foursquare and Starbucks. Foursquare is a mobile social network, and in addition to the handy “friend finder” feature, you can use it to find new and interesting places around your neighborhood to do whatever you and your friends like to do. It even rewards you for doing business with sponsor companies, such as Starbucks. The individual with the most “check in’s” at a particular Starbucks holds the title of mayor. For a period of time, the mayor of each store got $1 off a Frappuccino. Those who used Foursquare were particularly excited about Starbucks’s nationwide mayor rewards program because it brought attention to the marketing possibilities of the location-sharing app.[38]

Free coffee on tax day (via Twitter’s promoted tweets)

Starbucks was not the only company to give away freebies on Tax Day, April 15, 2010. Lots of others did.[39] But it was the only company to spread the message of their giveaway on the then-new Twitter’s Promoted Tweets platform (which went into operation on April 13, 2010). Promoted Tweets are Twitter’s means of making money by selling sponsored links to companies.[40] Keeping with Twitter’s 140 characters per tweet rule, Starbucks’s Promoted Tweet read, “On 4/15 bring a reusable tumbler and we’ll fill it with brewed coffee for free. Let’s all switch from paper cups.” The tweet also linked to a page that detailed Starbucks’s environmental initiatives.[41]

Free pastry day (promoted through Twitter and Facebook)

Starbucks’s “free pastry day” was promoted on Facebook and Twitter.[42] As the word spread from person to person in digital form, the wave of social media activity drove more than a million people to Starbucks’s stores around the country in search of free food.[43]

As word of the freebie offering spread, Starbucks became the star of Twitter, with about 1 percent of total tweets commenting on the brand. That’s almost 10 times the number of mentions on an average day. It performed equally well on Facebook’s event page where almost 600,000 people joined their friends and signed up as “attendees.”[44] This is not surprising given that Starbucks is the most popular brand on Facebook and has over 36 million “likes” in 2016.[45]

How did Starbucks achieve this notoriety on Facebook? According to social media marketing experts, Starbucks earned this notoriety by making social media a central part of its marketing mix, distributing special offers, discounts, and coupons to Facebook users and placing ads on Facebook to drive traffic to its page. As explained by the CEO of Buddy Media, which oversees the brand’s social media efforts, “Starbucks has provided Facebook users a reason to become a fan.”[46]

Social Media Marketing Challenges

The main challenge of social media marketing is that it can be very time consuming. It takes determination and resources to succeed. Small companies often lack the staff to initiate and manage social media marketing campaigns.[47] Even large companies can find the management of media marketing initiates overwhelming. A recent study of 1,700 chief marketing officers indicates that many are overwhelmed by the sheer volume of customer data available on social sites, such as Facebook and Twitter.[48] This is not surprising given that in 2016, Facebook had more than 1.6 billion active users,[49] and 500 million tweets are sent each day.[50] The marketing officers recognize the potential value of this data but are not always capable of using it. A chief marketing officer in the survey described the situation as follows: “The perfect solution is to serve each consumer individually. The problem? There are 7 billion of them.”[51] In spite of these limitations, 82 percent of those surveyed plan to increase their use of social media marketing over the next 3 to 5 years. To understand what real-time information is telling them, companies will use analytics software, which is capable of analyzing unstructured data. This software is being developed by technology companies, such as IBM, and advertising agencies.

The bottom line: what is clear is that marketing, and particularly advertising, has changed forever. As Simon Pestridge, Nike’s global director of marketing for Greater China, said about Nike’s marketing strategy, “We don’t do advertising any more. Advertising is all about achieving awareness, and we no longer need awareness. We need to become part of people’s lives, and digital allows us to do that.”[52]

A New Marketing Model

The 4 P’s have served marketers well for generations, but new innovations can disrupt even the most established concepts. A new framework is taking hold in marketing—the 4 C’s. In this model, each of the C words replaces one of the P’s, flipping the model from the perspective of the marketer to that of the customer. In the new model:

- Consumer replaces Product: Products solve a need for a customer; by focusing on the consumer in the 4 C’s model, the point of view changes to a customer-based perspective and also allows for the inclusion of services, which are purchased about as often as physical products.

- Convenience rather than Place: Both words speak to the same point—where can my customers obtain my product or service? But in an age where so many products and services are sourced online, the word “convenience” incorporates more than just a physical location, as was implied by the word “place.”

- Cost takes the place of Price: From the standpoint of the buyer, the price charged by the seller becomes their cost. Moving to the word “cost” results in seeing things from the perspective of the customer, consistent with other aspects of the model.

- Communication replaces Promotion: In its most basic form, promotion is about informing potential customers so that they will recognize the value in a product or service and part with the funds necessary to obtain it. However, the word “promotion” also has taken on the context of a deal or discount. By moving to the word “communication,” the new model incorporates all forms of reaching customers, whether through advertising, coupons, social media campaigns, and many others.

The 4 C’s framework appears to be gaining traction, and it may eventually replace the 4 P’s altogether. If so, we will no doubt find ourselves rewriting this entire chapter!

Chapter Video

Marketing is unfortunately not always truthful or entirely accurate. This video features some examples of misleading advertising which persists in business because it often works.

(Copyrighted material)

Key Takeaways

- Marketing is a set of processes for creating, communicating, and delivering value to customers and for improving customer relationships.

- A target market is a specific group of consumers who are particularly interested in a product, would have access to it, and are able to buy it.

- Target markets are identified through market segmentation—finding specific subsets of the overall market that have common characteristics that influence buying decisions.

- Markets can be segmented on a number of variables including demographics, geographics, behavior, and psychographics (or lifestyle variables).

- Developing and implementing a marketing program involves a combination of tools called the marketing mix: product, price, place, and promotion.

- Before settling on a marketing strategy, marketers often do marketing research to collect and analyze relevant data.

- Methods for collecting primary data include surveys, personal interviews, and focus groups.

- To protect a brand name, companies register trademarks with the US Patent and Trademark Office.

- There are three major branding strategies:

- With private branding, the maker sells a product to a retailer who resells it under its own name.

- Under generic branding, a no-brand product contains no identification except for a description of the contents.

- Using manufacturer branding, a company sells products under its own brand names.

- When consumers have a favorable experience with a product, it builds brand equity.

- If consumers are loyal to it over time, it enjoys brand loyalty.

- Retailers are intermediaries that sell to the end consumer. Types of retailers include category killers, convenience stores, department stores, discount stores, specialty stores, supermarkets, and warehouse club stores.

- The promotion mix includes all the tools for telling people about a product and persuading potential customers to buy it. It can include advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, and publicity.

Image Credits: Chapter 14

Figure 14.3: ProjectManhattan (2013). “McDonald’s Ebi Burger, Sold in Singapore in November 2013.” Wikipedia. Public Domain. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/McDonald’s#/media/File:Ebi_burger.jpg

Figure 14.8: Metropolitan Transportation Authority (2014). “Subway Station Digital Advertising Screens.” Flickr. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved from: https://flic.kr/p/mbWQNB

Figure 14.9: Intel Free Press (2012). “Ultrabook Zone Best Buy.” Flickr. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/54450095@N05/8164405406

Figure 14.10: Wal-Mart (2011). “Walmart’s “Action Alley.” Display Signs Feature Value and Convenience on Popular Shopping Items.” Flickr. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/walmartcorporate/5684811762

Figure 14.11: Aaina Sharma (2017). “Airpods.” Unsplash. Public Domain. Retrieved from: https://unsplash.com/photos/rI2MXeP6sss

Video Credits: Chapter 14

WatchMojo (2014, September 24). “Top 10 Misleading Marketing Tactics.” YouTube. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M-HrTC8QCbM

- WowWee Toys (n.d.). “Robosapien: A Fusion of Technology and Personality.” Retrieved from: http://wowwee.com/robosapien-x ↵

- Michael Taylor (2004). "Innovative Toy Packs a Punch." South China Morning Post (Hong Kong). Retrieved from: http://www.scmp.com/article/478240/innovative-toy-packs-punch ↵

- WowWee Toys (n.d.). “Our Story.” Retrieved from: http://wowwee.com/about/company-history ↵

- American Marketing Association (2013). “Definition of Marketing.” Retrieved from: https://www.ama.org/AboutAMA/Pages/Definition-of-Marketing.aspx ↵

- Funding Universe (n.d.). “Medtronic Inc. History.” Retrieved from: http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/medtronic-inc-history/ ↵

- Michael Arndt (2004). “High Tech—and Handcrafted.” Bloomberg. Retrieved from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2004-07-04/high-tech-and-handcrafted ↵

- Hyundai Motor America (2016). “Special Programs: College Graduate Program.” Hyundai USA. Retrieved from: https://www.hyundaiusa.com/financial-tools/college-grad-program.aspx ↵

- Pacific Business News (2002). “McDonald’s Test Markets Spam.” The Business Journals. Retrieved from: http://www.bizjournals.com/pacific/stories/2002/06/10/daily22.html ↵

- Svenske chef (2002). “The Super McDonalds.” Halfbakery. Retrieved from: http://www.halfbakery.com/idea/The_20Super_20McDonalds ↵

- Tucker S. Cummings (2010). “Interesting Menu Items from McDonalds in Asia.” Weird Asia News. Retrieved from: http://www.weirdasianews.com/2010/03/23/blank-interesting-menu-items-mcdonalds-asia/ ↵

- Time (2003). “Best Inventions 2003: Hybrid Car.” Retrieved from: http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1935038_1935083_1935719,00.html ↵

- James L. McQuivey and Gina Fleming (2012). “Segmenting Customers by Technology PreferenceMaking Technographics® Segmentation Work.” Forrester. Retrieved from: https://www.forrester.com/report/Segmenting Customers By Technology Preference/-/E-RES72761 ↵

- Information in this section was obtained through an interview with the director of marketing at Wow Wee Toys Ltd. conducted on July 15, 2004. ↵

- Brendan Light (2004). “Kellogg’s Goes Online for Consumer Research.” Packaging Digest. Retrieved from”: http://www.packagingdigest.com/kellogg-s-goes-online-consumer-research ↵

- Marriott (2016). “Autograph Collection Hotels.” Retrieved from: http://www.autograph-hotels.marriott.com/ ↵

- Interbrand (2016). “Rankings.” Interbrand.com. Retrieved from: http://interbrand.com/best-brands/best-global-brands/2015/ranking/ ↵

- The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company LLC (2016). “Gold Standards.” Retrieved from: http://www.ritzcarlton.com/en/about/gold-standards ↵

- G6Hospitality LLC (2015). “Corporate Profile.” Motel 6. Retrieved from: https://www.motel6.com/en/faq.html ↵

- Caitlin A. Johnson (2009). “Cutting Through Advertising Clutter.” CBS News. Retrieved from: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/09/17/sunday/main2015684.shtml ↵

- Louise Story (2007). “Anywhere the Eye Can See, It’s Likely to See an Ad.” New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/15/business/media/15everywhere.html?pagewanted=all ↵

- Seth Godin (1999). Permission Marketing: Turning Strangers into Friends, and Friends into Customers. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 31. ↵

- Paul Gough (2002). “Nantucket Nectars: New Flavors, Old Ad Strategy.” Media Post. Retrieved from: http://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/2812/nantucket-nectars-new-flavors-old-ad-strategy.html?edition= ↵

- Kevin J. Clancy (2001). “Sleuthing, Not Slashing, for Growth.” Across the Board. Vol. 38. No. 5. p. 9. ↵

- Daphne Howland (2016). “Best Buy CEO: Customer Service Key to Battling Amazon.” Retail Dive Retrieved from: http://www.retaildive.com/news/best-buy-ceo-customer-service-key-to-battling-amazon/419812/ ↵

- Burt Helm (2014). “How Dr. Dre's Headphones Company Became a Billion-Dollar Business.” Inc. Retrieved from: http://www.inc.com/audacious-companies/burt-helm/beats.html ↵

- Korn Ferry Institute (2016). “FORTUNE World’s Most Admired Companies.” Korn Ferry. Retrieved from: http://www.kornferry.com/institute/fortune-worlds-most-admired-companies ↵

- Fortune (2016). “World’s Most Admired Companies 2016.” Retrieved from: http://fortune.com/worlds-most-admired-companies/ ↵

- Alex Lawrence (2012). “Five Customer Retention Tips for Entrepreneurs.” Forbes. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/alexlawrence/2012/11/01/five-customer-retention-tips-for-entrepreneurs/#56de8ec717b0 ↵

- Stephanie Fitch (2004). “Stacking the Deck.” Forbes. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/forbes/2004/0705/132.html ↵

- Hotel News Resource (2004). “Sheraton Hotels Lure Travelers With the Promise of a Good Night's Sleep in New Million Television and Print Ad Campaign.” Retrieved from: http://www.hotelnewsresource.com/article10706.html ↵

- Seth Godin (1999). Permission Marketing: Turning Strangers into Friends, and Friends into Customers. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 40-52. ↵

- ALS Association (n.d.). “ALS Ice Bucket Challenge – FAQ.” Retrieved from: http://www.alsa.org/about-us/ice-bucket-challenge-faq.html?referrer=https://www.google.com/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Leah Betancourt (2010). “Social Media Marketing: How Pepsi Got It Right.” Mashable. Retrieved from: http://mashable.com/2010/01/28/social-media-marketing-pepsi/#PH_2T_7ZKEq7 ↵

- Mountain Dew (2016). “DEWcision 2016 Challenges.” Retrieved from: http://www.mountaindew.com/dewcision2016/challenges ↵

- Leah Betancourt (2010). “Social Media Marketing: How Pepsi Got It Right.” Mashable. Retrieved from: http://mashable.com/2010/01/28/social-media-marketing-pepsi/#PH_2T_7ZKEq7 ↵

- Zachary Sniderman (2010). “5 Winning Social Media Campaigns to Learn From.” Mashable. Retrieved from: http://mashable.com/2010/09/14/social-media-campaigns/#R7bMibHpKaq7 ↵

- Jennifer van Grove (2010). “Mayors of Starbucks Now Get Discounts Nationwide with Foursquare.” Mashable. Retrieved from: http://mashable.com/2010/05/17/starbucks-foursquare-mayor-specials/#1E9sN9cxPiqk ↵

- Jennifer Van Grove (2010). “Celebrate Tax Day with Free Stuff.” Mashable. Retrieved from: http://mashable.com/2010/04/15/tax-day-2010-freebies/#bkRuURIJKmq2 ↵

- Amir Efrati (2011). “How Twitter’s Ads Work.” Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2011/07/28/how-twitters-ads-work/ ↵

- Dianna Dilworth (2010). “Twitter Debuts Promoted Tweets; Virgin America, Starbucks Among First To Use Service.” Direct Marketing News. Retrieved from: http://www.dmnews.com/digital-marketing/twitter-debuts-promoted-tweets-virgin-america-starbucks-among-first-to-use-service/article/167885/ ↵

- Patsy Bustillos (2009). “Starbucks Free Pastry Day: July 21, 2009.” Facebook. Retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/patsy.bustillos/posts/103702604431 ↵

- Jennifer Van Grove (2010). “Starbucks Used Social Media to Get One Million to Stores in One Day.” Mashable. Retrieved from: http://mashable.com/2010/06/08/starbucks-mashable-summit/#bkRuURIJKmq2 ↵

- Adam Ostrow (2009). “Starbucks Free Pastry Day: A Social Media Triple Shot.” Mashable. Retrieved from: http://mashable.com/2009/07/21/starbucks-free-pastry-day/#DytKqtxcPqqp ↵

- Starbucks (2016). “Starbucks.” Facebook. Retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/Starbucks/ ↵

- Mark Walsh (2010). “Starbucks Tops 10 Million Facebook Fans.” MediaPost Marketing Daily. Retrieved from: http://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/132008/ ↵

- Susan Ward (2016). “What is Social Network Marketing?” The Balance Small Business. Retrieved from: http://sbinfocanada.about.com/od/socialmedia/g/socmedmarketing.htm ↵

- Georgina Prodhan (2011). “Marketers Struggle to Harness Social Media – Survey.” Reuters. Retrieved from: http://www.reuters.com/article/socialmedia-ibm-idUSL5E7LA3JO20111011 ↵

- Statista (2016). “Number of Monthly Active Facebook Users Worldwide as of 1st Quarter 2016 (in Millions).” Retrieved from: http://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/ ↵

- Internet Live Stats (2016). “Twitter Usage Statistics.” Watch the ticker count tweets here: http://www.internetlivestats.com/twitter-statistics/ ↵

- Georgina Prodhan (2011). “Marketers Struggle to Harness Social Media – Survey.” Reuters. Retrieved from: http://www.reuters.com/article/socialmedia-ibm-idUSL5E7LA3JO20111011 ↵

- Johan Ronnestam (n.d.). “Simon Pestridge from Nike Makes Future Advertising Sound Simple.” Ronnestam. Retrieved from: http://www.ronnestam.com/simon-pestridge-from-nike-make-future-advertising-sound-simple/ ↵