10 The Power of Extension: Research, Teaching, and Outreach for Broader Impacts

Jeremy Elliott-Engel; Courtney Crist; and Gordon Jones

Introduction

The land-grant university (LGU) system was created on a foundation of three missions: classroom-teaching, research, and a specific type of community education called Extension[1]. The majority of this book has highlighted and focused on the formal higher-education classroom-teaching experience of the mission, and your doctoral program has provided training on the research component. This chapter will focus on the third mission, Extension (at non-LGU institutions similar efforts may be called outreach, engagement, or service). The Cooperative Extension System (CES) has a mission to translate research-based findings, best practices, and information in four broad program areas: youth development (4-H), agriculture and natural resources (ANR), family and consumer sciences (FCS), and community development (Seevers et al., 2007). Land-grant universities employ Extension educators to work from campus and state regional centers, as well as in local county or city offices to deliver Extension education programs based on stakeholder needs—including state, industry, and community needs (Baughman et al., 2012). It should be noted that university and state Extension organizational structures and program priority areas differ by state.

Extension educators offer nonformal educational programs to both businesses and the citizens of their communities. Local Extension educators are supported by research and Extension faculty across departments from the LGU. To start our journey to understanding what Extension education is, and how you, as a future or current LGU faculty member and researcher, will support Extension education, we will recount the history of the LGU mission, then introduce a learning theory for nonformal education, and finally explain the unique planning processes of Extension education programs.

The objectives of this chapter are to provide a translation of effective teaching practices from the higher-education classroom and emphasize the interconnections of teaching and research disciplines to impactful community outreach, engagement, and impact.

This chapter will discuss…

- The origin and mission of the land-grant university system.

- Educational theory utilized in non-formal educational settings.

- Educational learning contexts and environments outside of the formal classroom.

- How to establish and integrate a research, teaching, and outreach educational program to support broader impacts

What Is Extension?

The use of the word “Extension” derives from an educational development in England during the second half of the nineteenth century. Around 1850, discussions began in the two ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge about how they could serve the educational needs, near to their homes, of the rapidly growing populations in the industrial, urban area. It was not until 1867 that a first practical attempt was made in what was designated “university Extension,” but the activity developed quickly to become a well-established movement before the end of the century. (Jones & Gartforth, 1997, p. 1)

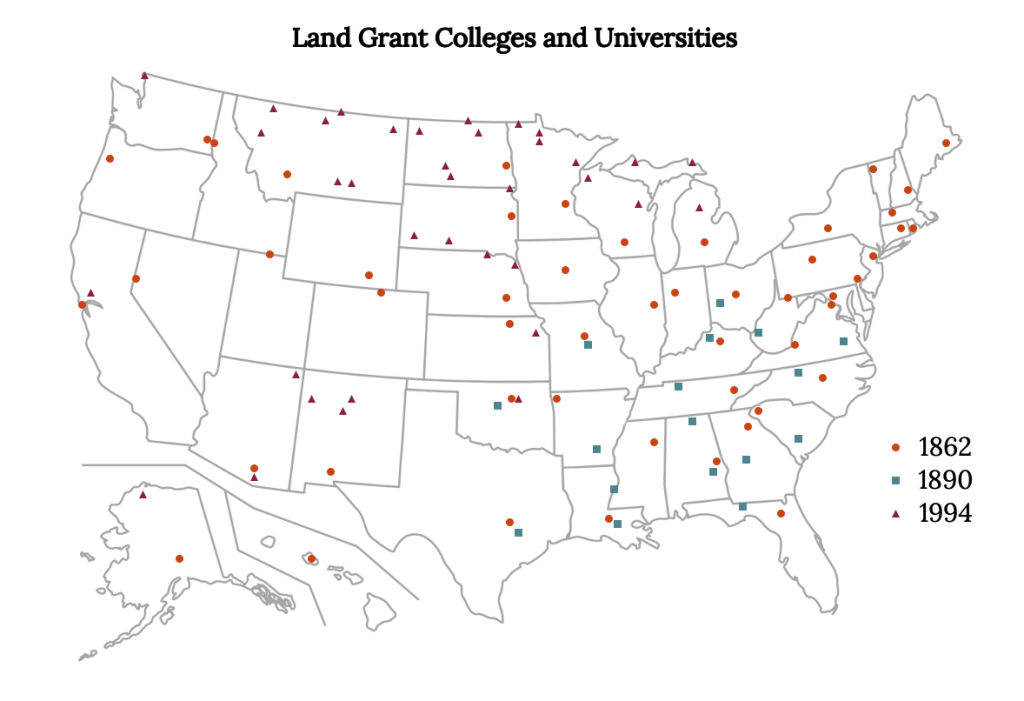

The idea of Extension started in the late nineteenth century in both the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (US) with three components: adult education, technology transfer, and advisory services (Shinn et al., 2009). In the United States, the development of the Extension system started on July 2, 1862, when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Land-Grant College Act (Morrill Land-Grant Act, 1862). This legislation forming the LGU system was sponsored by Vermont Senator Justin Smith Morrill. Passage of the Morrill Act was unexpected because President James Buchanan had previously vetoed a version of the act in June 1860 due to Southern state representatives’ criticisms that granting Western territorial land was an imprudent use of resources. The Western territorial lands were lands taken from Native Americans by the US government. The bill that was vetoed had granted just 2,000 acres for a university’s setup. The successful version of the Morrill Act granted 30,000 acres of Western territorial land as an endowment to establish at least one college per state and territory (Wessel & Wessel, 1982). The Morrill Act successfully passed in 1862 largely because Southern states representatives were absent from Congress at the time of the vote due to the Civil War (Lee, 1963).

The established purpose of the LGU institutions is to make liberal and practical education available to all citizens of the nation, particularly the working class (Duemer, 2007; Depauw & McNamee, 2006; Lee, 1963; Simon, 1963). To achieve this mission the Morrill Act and its successors were deliberately designed not simply to encourage, but to force the states to significantly increase their efforts on behalf of higher education. The federal government, having promoted the establishment of new colleges, made it incumbent upon the states to supply the means of future development and expansion (Lee, 1963, p. 27). The LGUs married the humanistic idea of the renaissance university (liberal education) and the German university (practical education) (Bonnen, 1998). This combination of liberal and practical education in one institution was designed to democratize education and provide educational opportunities for all citizens. The LGUs evolved into entities with a three-pronged mission of research, teaching, and outreach (Simon, 1963).

In 1890, a second Morrill Act was passed, which prohibited the distribution of money to states that made race a consideration when making decisions about admission to their state’s 1862 LGU institution (Lee & Keys, 2013). Each state had to demonstrate that race was not a criterion when considering a student’s admission to the LGU. If Blacks or other persons of color were unable to be admitted because of race, then a separate LGU was established for them (Comer et al., 2006). This resulted in 19 previously slave-holding states establishing public colleges serving Blacks (Allen & Jewell, 2002; Provasnik et al., 2004; Redd, 1998; Roebuck & Murty, 1993). These “1890” institutions were awarded cash in lieu of land; however, they retain the designation of “land grant” due to the legislation. The 1890 institutions brought public and practical education to previously excluded and marginalized populations.

In 1994, the Equity in Educational Land-Grant Status Act established 29 tribal colleges and universities as “1994” tribal land-grant institutions. These institutions have a mission to provide federal government resources to improve the lives of Native American students through higher education (USDA-NIFA, 2015).

The three current missions of research, teaching, and outreach were achieved through additional legislation. The 1887 Hatch Experiment Station Act (Hatch Act) established the State Agricultural Experiment Station (SAES) to improve agricultural production through applied agriculture research and to provide educational outreach opportunities through the LGUs (Knoblauch et al., 1962). Joining the locally responsive research from the SAES with the LGUs expanded the capacity for classroom education and provided the opportunity to share knowledge onsite at research stations across each state. However, to extend the positive benefits of knowledge farther afield, more efforts were needed. Cooperative Extension began when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Smith-Lever Act into law on May 8, 1914. The purpose of Extension was declared to be an effort “to aid in diffusing among the people of the U.S. useful and practical information on subjects related to agriculture and home economics, and to encourage the application of the same” (Rasmussen, 1989, p. 7). The Smith-Lever Act did not specifically state that Extension services should only work with farmers (Ilvento, 1997; Rogers, 1988). Extension was designed to take the research-based knowledge generated at the LGUs and the SAES to US citizens through a partnership between LGUs and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The implementation of this organizational system had significant and profound effects on adult education in the United States. Liberty Hyde Bailey, a renowned botanist and Cornell faculty member, was instrumental in the formation of the Extension service and 4-H; he argued that Extension could not address agricultural production issues without also addressing the social and human issues facing rural communities (Ilvento, 1997; Rosenberg, 2015). At the time, he lost the argument to Seaman Knapp, then president of Iowa Agricultural College, who laid the foundation of the Agricultural Experiment stations as an employee of the USDA. Knapp argued the role of Extension was solely to educate reluctant farmers on new technology (Ilvento, 1997; Peters, 1996). Because of Knapp’s influence, the purpose of Extension began as instruction and practical demonstration concerning agriculture and home economics for individuals in communities across the state who would otherwise not have access to information and new innovations.

The name Cooperative Extension emerged from the cost sharing, which required using state and local funding sources to match the funds contributed by the USDA. Currently, federal partners supply approximately 30 percent of the system’s financial resources, while state and local (e.g., county) funds make up the remaining portion of the budget (Rasmussen, 1989). Further, following funding trends within higher education, a growing share of Extension budgets consists of extramural grants and contracts (Jackson & Johnson, 1999).

The focus of US Extension work has evolved from primarily relaying technical innovation to also providing leadership for social, cultural, and community change and development (Stephenson, 2011) by partnering with communities to identify solutions to challenges in partnership (Vines, 2017). As previously mentioned, this adaption reflects a move toward Bailey’s perspective that community programming cannot provide technical knowledge without first supporting the individual and social needs of the participants. Extension, because of the nature of the organization, has always engaged with communities, and more importantly, has acted as an accessible and knowledgeable resource for the communities they serve. Extension professionals have sought to respond to society and community needs, whether in response to supporting a reduction of poverty in rural communities (Rogers, 1988; Selznick, 2011) or helping the nation survive World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II (Rasmussen, 1994) by ensuring the sustainability of food resources, and by supporting rural electrification (Rosenberg, 2015), rural telephone, and today, broadband access (Whitacre, 2018). The mission of Extension has expanded from a focus on agriculture and family and consumer sciences to incorporate areas of health, community, and business development, and from solely rural audiences to rural, suburban, and urban communities (Morse, 2009; DePauw & McNamee, 2006). While work remains to be done, 1862 LGUs in every state and territory work to serve a demographically representative population and address community challenges (Elliott-Engel, 2018), and 1890 and 1994 LGUs target historically underserved populations with specific interventions.

What Is Extension Education?

Early practitioners of … Extension education drew from foundational theories of learning and teaching (Dewey, 1938; James, 1907; Lancelot, 1944). During the early evolution, knowledge was grounded in observation and experience and passed to others through direct engagement methods. Over time, …Extension education integrated the principles of learning and teaching, applied research, and Extension outreach. Today’s field of study draws from educational psychology and the works of Bandura (1977), Bruner (1966), Gagné (1985), Knowles (1975), Piaget (1970), Thorndike (1932), Vygotsky (1978), and others. Perspectives of learning rise from the educational theories of behaviorism and constructivism, while the perspectives of teaching are drawn from the works of Freire (1972), Habermas (1988), Kolb (1984), Lewin (1951), and others who advanced problem solving, critical thinking, and communicative reason. (Shinn et al., 2009, p.77)

Extension is an organization that continuously plans, executes, and evaluates programs with learners (Meena et al., 2019, p. 17) and updates or modifies as needed. Extension education is a knowledge exchange system that engages change agents in a participatory persuasive process of educating stakeholders in a changing world (Shinn et al., 2009). Extension educators are professionals in the social, behavioral, and natural and life sciences who use sound principles of teaching and learning, and they integrate the sciences relevant for the development of human capital and for the sustainability of agriculture, food, renewable natural resources, and the environment (Shinn et al., 2009).

Extension education can be conducted and executed in many forms including in-person education (e.g., workshops, seminars, demonstrations, short courses), publication (e.g., website, print media), and using social media (e.g., infographics). In many non-LGU institutions, Extension is commonly referred to as community outreach or engagement. These terms originated in the Extension education movement. The work, when adopted, contributes to the democratic process of encouraging institutions of higher education to help extend research efforts beyond the students in the classroom and fellow researchers in academe to communities or businesses where it can be directly applied.

There are several principles that are important to keep in mind to ensure success in extending research and knowledge outside the higher education environment. The education of community members has different principles than the formal education setting. In formal education settings, motivation is incentivized by earning grades needed to receive certification through the earning of a degree. In nonformal education settings, education centers around learners’ motivations to obtain the knowledge being offered and its impact on their livelihood or success.

Nonformal Education Theory

Nonformal education is the learning instruction provided beyond the traditional secondary education system designed to prepare individuals (adolescents and adults) to achieve their personal, social, and economic life goals (Okojie, 2020). When extending their research beyond the formal classroom, the educator becomes an adult and nonformal educator, also known as an Extension educator. Extension educators remain intentional and systematic while also recognizing content can and should be adapted for different clientele (Etling, 1993).

Researchers have defined adult learners in overlapping but somewhat different ways. Merriam (2008) describes adult learners as those whose age, social roles, and self-perception define them as adults. Adult learning theory is informed by foundational scholars in related fields such as psychology and sociology. The theories of behaviorism, cognitivism, humanism, constructivism, and connectivism illuminate different learner types and their disposition toward the process of education (Balakrishnan, 2020). The main ideas, approaches, and contributions of these theories have been summarized for your reference in table 10.1. The denotation of the theory, approach, and application is indicated by the theorists’ major works and forthcoming implications.

| Theorist/ Thinker | Approach/Premise | Definition of Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Émile Durkheim | Sociology of Education | Education is a social process. |

| B. F. Skinner | Behaviorism | Demonstration of learning is a resultant change or modification in behavior, largely overt behavior. |

| Jean Piaget | Cognitivism | Teaching and learning results from observation, attention and personal involvement by the teacher along with practice aimed at bringing out individual capabilities. |

| Abraham Maslow

Carl Rogers |

Humanistic | Human capacity for choice and growth, and inner emotions is needed to effectively learn. Maslow linked readiness to learn to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Rogers argued learning needs to be student-centered and personalized. |

| Jean Piaget | Constructivism | Learning is facilitated by providing an environment that promotes discovery and assimilation/accommodation. |

| Lev Vygotsky | Social Constructivism | Collaborative learning occurs in the presence of facilitation and guidance. Group work is encouraged. |

| George Siemens | Connectivism | Behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism are used together. Learning is about knowledge distribution across an information network, storage, connectivity and new forms of learning communities. |

| David Kolb | Experiential Learning | Abstract concepts are easier to comprehend based on practice. |

| Vincent Tinto | Interactionalist | Persistence and departure from learning programs is a result of individual and environmental factors. |

| Alexander Astin | (Student) Involvement | Change and development is an output of curricular and cocurricular factors. |

| John Bean & Barbara Metzner | Persistence (model) | Nontraditional students have specific requirements for retention, attrition, and persistence. |

| Malcolm S. Knowles | Andragogy | Adults need autonomy and self-directedness in learning programs. |

| Albert Bandura | Social Learning | Learning is from peers through methods like observation, modeling, and imitation. |

| Everett Rogers | Adoption of Innovation | Learning is represented by adoption (use) of new technology and innovation. |

Each theorist presents a systematic explanation for the observed facts and laws that relate to a specific aspect of life (Williamson, 2002), in this case the nonformal learner. Each of the theorists allows the Extension educator to conceptualize the learner in different ways. The nonformal learners bring their lived experiences, and thus, their varied motivations to the educational process. The educator in the nonformal context must think about barriers to participation and adoption (Rogers, 2003) of the practice or materials presented.

Nonformal Education Is Present Everywhere

The nonformal educator views all contexts and environments as a possible classroom and everyone as a possible student. The educator working with or through Extension (Extension Educator) has the flexibility to extend research and technical knowledge across many meaningful educational strategies (Fordham, 1979). The variety of strategies provides the Extension educator much greater flexibility, versatility, and adaptability than their formal classroom educator counterpart to meet the diverse learning needs of each clientele, and to adapt as those needs evolve (Coombs, 1976). Education can happen within numerous contexts. Common educational strategies for Extension education can be broken into three broad categories: An Extension educator can support a learner’s knowledge change through (1) face-to-face programming, (2) print, and (3) social media. Each approach has unique considerations for teaching and learning across areas of content, which are discussed below.

Face-to-Face

Many methods exist for engaging learners in person, and each uses a different approach to disseminating research. Clientele and subject matter will largely drive the type of face-to-face instruction. While many of the same teaching strategies for formal education can be applied in the nonformal educational setting, it is important to note the differences. For example, in most Extension programming, you will not assign homework and will not be giving graded assignments. Also, your learners need to be engaged with real-world relevance—this should also happen in a formal education setting, but sometimes this connection is forgotten. Learners also bring their own lived experiences and expertise into the learning environment. Many different strategies can be implemented and each has a different educational approach.

The in-person strategies vary from one-on-one training or consulting to large format training, to groups of learners co-developing knowledge, or applied hands-on demonstrations. You will notice that each of these teaching and learning modes connect to the theoretical constructs of learning in table 10.1.

Direct client support, such as technical assistance, is a large component of Extension specialists’ responsibilities. Stakeholder needs can vary with program area or content. Often, in specific circumstances, specialists may visit clients at their operations to assist directly with troubleshooting, system improvement, pilot testing, or optimizing methods. Extension has a rich history of disseminating information and teaching best practices to the stakeholders they serve. Each discipline may have a different approach or structure for assisting clients. Client assistance is largely dependent on the client’s current state and needs. As an example, food science (family and consumer sciences) provides a wide array of services to clientele including food safety consultation on process deviations, interpretation of laws, labeling review, educational information, shelf-life information, product analysis, food safety training, and meeting the requirements for processing and selling food.

Diversity

The work of Extension provides an opportunity for educating and connecting with all of society in a state and/or local region rather than solely those connected to higher education. It is important to develop Extension programs and supporting materials that are inclusive of the broad range of human experiences, cultures, resources, and identities, and to be sensitive to the systemic disadvantage that many groups have experienced (Farella, Moore, et al., 2021). We should strive to remember that programs which have historically been offered by the Extension Service were designed to cater to the needs of the majority, and that we have a responsibility to design—or redesign—our Extension programs to be equitable and meet the needs of everyone (Farella, Hauser et al., 2021; Fields, 2020). Careful assessment of the needs of the communities we serve and, in many cases, further understanding for ourselves as educators, are required to develop inclusive, accessible, and culturally sensitive programming.

Extension provides services such as seminars, training, continuing education, and certifications for clients ranging from producers to general public interest. Extension has and provides the subject matter experts to deliver these training and educational opportunities in diverse content areas. Further, Extension often has a public reputation for disseminating reliable information without bias. Training may be presented in collaboration with state and/or federal regulatory agencies or may be provided to meet regulatory standards and requirements outlined by governing agencies. For example, American National Standards Institute (ANSI) certification (e.g. ServSafe, Safe Plates), Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs), related certifications of Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), and Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) trainings and certifications are required by regulatory agencies depending on the sector of the industry. In agriculture, Extension educators deliver programs which provide continuing education credits for pesticide applicators and programs like Beef Quality Assurance for livestock producers. Extension specialists and personnel/agents often offer these training and certifications as part of their programmatic planning in a way to serve stakeholders. Extension trainers may need additional training and experience to certify participants and lead state training sessions.

Similar to research collaborations, Extension educators also collaborate with colleagues in other states, counties, departments, and universities to diversify and expand programmatic efforts to a wider audience. Expertise among state Extension systems can vary and collaboration allows for better programming that serves both stakeholders and Extension educators. and Additionally, within the university, course collaborations are useful as clients may need topic diversity. Generally, entrepreneur series include speakers from across departments (i.e., varied subject areas) as well as topics to provide a general introduction to the subjects.

Using the Food industry as an example, subject matter experts represent agricultural economics, government/regulatory agencies, marketing, food safety, and business (Crist & Canales, 2020). These programs provide stakeholders a foundation of information as well as contacts in the event they need further assistance in that specific subject area. Recently, Extension program delivery has shifted toward using more online educational platforms, certification programs, expert happy hours, and “lunch and learn” series in order for stakeholders to access the information they need as well as provide a forum for questions.

Extension specialists–faculty with a content area focus– can provide programmatic and subject matter competency in-service opportunities and training to Extension agents–county-based Extension professionals. Inservice training is considered continuing education and an opportunity to increase subject matter competency. Further, agents select the programs that they will deliver in the county. Specialists provide in-service training to agents so they may deliver these programs as intended and/or provide additional insight to the execution of the program. Inservice opportunities can include many topics and range in subject matter from youth development to agriculture and natural resources. Further, inservice training is provided throughout the year and on different education platforms including webinars, face-to-face training or lectures, and online platforms.

Syllabus Development

As Extension educators, it is important to make connections for students in traditional education to career paths and opportunities. As a group, Extension educators need to advocate and share their stories and passion with audiences that may not be familiar with the unique career opportunities of Extension, as most will associate higher education with the pillars of research and teaching. Some students may be familiar with part of Extension either through 4-H involvement or by having parents who were involved in educational offerings (e.g., master gardener). You can strengthen the connection of careers in Extension by incorporating assignments, presentations, and curriculum development into courses. Additionally, your institution may have Extension apprenticeship programs. These types of programs can be a valuable opportunity for students to learn more about the day-to-day Extension roles while at the same time impacting their communities. Integrating some of our communication pathways into syllabi or student experiences will expose them to the multifaceted world of Extension.

Community of Practice

The Communities of Practice (CoP) framework is constructed from the exchange of a group of people who have a shared interest and want to improve on that interest using regular interactions with each other to accomplish that development (Wenger, 1998). Lave and Wenger (1991) introduced CoP to provide a template for examining the learning that happens among practitioners in a social environment comprising both novices and experts. Newcomers use this exchange between these populations to create a professional identity. Wenger (1998) then advanced the focus of CoP to personal growth and the trajectory of individuals’ participation within a group (i.e., peripheral versus core participation). No matter the purpose of educational outcome, CoPs can be designed intentionally, fostered informally, or identified after they have developed organically. A CoP can also be an outcome from learning experiences (Elliott-Engel & Westfall-Rudd, 2018) that result from your strategy and lead to connecting people, providing a shared context, enabling dialogue, stimulating learning, capturing and diffusing existing knowledge, introducing collaborative processes, helping people organize, and generating new knowledge (Cambridge et al., 2005).

A great example of direct client support (and farm model training), as well as being the foundation of the Extension service, is boll weevil eradication. The boll weevil was an invasive insect pest that was devastating cotton crops throughout the South in the early 1900s. Seaman Knapp, who has been mentioned previously, was sent to Mississippi by the USDA to help find a solution to the boll weevil infestation. Knapp set up an experimental farm to demonstrate to growers’ methods for mitigating the boll weevil damage. The farm opportunity became the model for agricultural demonstration (Mississippi State University Extension Service, 2020; Palmer, 2014). Similar stories exist for other areas and educational formats. For example, the foundation of family and consumer sciences began with home-demonstration clubs that focused on improving nutrition and living conditions for rural families. These sessions continue today and address a variety of topics such as nutrition, cooking, health, mental health, financial literacy, volunteer programs, and home-based businesses (Mississippi State University Extension Service, 2020).

Print Communications

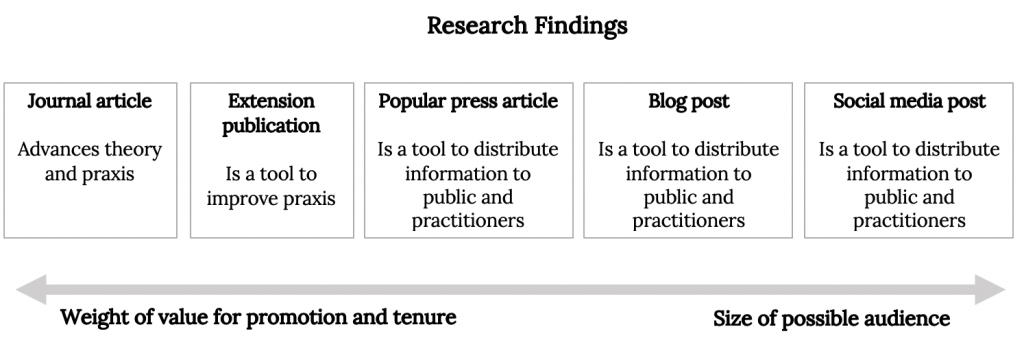

Print media is an important form of education delivery we often think of as andragogy rather than pedagogy. Most, if not all of us, have heard the phrase “publish or perish” in reference to faculty roles. This colloquialism emphasizes that print formats of education are highly valued in the academe. Yet, not all forms of print publication are equivalent or have the same credibility (e.g., burden of peer review), and thus their value is weighted differently by the institution’s Promotion and Tenure review board.

A successful Extension educator should formulate a plan of distribution that includes each level of communication. Figure 10.2 provides a framework for you to think through how you can take your research findings and translate these specific findings into all forms of print communication. An Extension educator should provide multiple communication formats to ensure that the research done on campus is communicated to the citizens of the state they serve.

It is unfortunate that social media and electronic options give the greatest reach for distributing research findings to a large audience and yet are weighted the least. Social media and other digital forms of publication are hard to evaluate for impact as well as implementation and/or behavior change. It would be easy to become hyperfocused on submitting publications to journals with a high-impact factor because that is what is favored for promotion. Yet, in Extension, we must ask, what is the value of creating new knowledge if it stays within the walls of the ivory tower? Extension’s purpose and mission is disseminating research-based evidence to improve the lives of the stakeholders they serve.

Social Media

Social media may not be commonly viewed as a pedagogical tool or accorded traditional forms of value in academe. However, it is a tool for rapidly spreading knowledge and its reach is hard to ignore in current society. Social media has evolved our consumption of both information and entertainment; it has also changed our preferences on how to consume new information (Subramanian, 2018). The use of social media provides the greatest opportunity to distribute research findings to a wide audience and to affect social discourse both positively and negatively. The field of science communication is rich, filled with best practices for effective outcomes, including language, strategy, and design. We won’t address those strategies here, yet we do want to emphasize the need to use and engage with social media and to view it as a platform for teaching. (For further reading on science communication, we recommend Laura Bowater & Kay Yeoman’s Science Communication: A Practical Guide for Scientists, New York: Wiley, 2012.)

In Conclusion: Extension Is a Bridge

Extension activities should be viewed as a bridge to enhancing and expanding the reach of research-based evidence and technical information from members of academe to stakeholders in need. Faculty who hold Extension appointments should funnel energy into sharing their findings to the betterment of society. Many grants and funding opportunities require a broader impact statement, outreach, expected outcomes, and evaluation component and approach. This is where Extension professionals should shine and can use their expertise to develop methods for reaching and educating the audience where the findings will be most impactful. The “traditional” researcher may overlook this area of importance, but many funding agencies are placing higher priority on proposals that address how the grant will impact or improve the affected stakeholders. The next chapter, “Program Planning for Community Engagement and Broader Impacts,” will further discuss how to develop and translate knowledge to benefit stakeholders.

Powerful and impactful teaching is rarely confined to the classroom. The Extension system and nonformal education are valuable for early career faculty members and graduate students. We hope that you will integrate the educational approaches from nonformal educational settings into your classroom and engage your learners with issues relevant to our communities.

Not every reader will be an Extension specialist or a county-based Extension professional (a.k.a., Agent), nor will every reader even work at an LGU. However, all faculty have the motivation, if not the obligation, to share findings from your research agenda to the public. Many times this outreach is labeled as “broader impacts” (Donovan, 2019). We hope this chapter helps you see how your teaching and research can become integral to your community. If you are a graduate student seeking a position in higher-education, we hope this chapter has raised your interest in Extension education at LGUs or in developing better ways to communicate your ideas about how to bring community-relevant research and teaching to your research agenda.

If you are reading this while working or studying at a LGU institution we hope this chapter has raised your awareness of the mission of your institution, and that you will seek out Extension professionals to help you in your teaching, research, and outreach efforts. If you do become an Extension specialist, or a county-based 4-H professional, congratulations! You are in for a challenging and rewarding career. We hope this chapter serves as a framework for conducting excellent Extension education programming and provides a greater awareness of the organization’s beginnings, the theory that frames the work, and some basic practices of non-formal education that you can use to maximize community outreach efforts.

Reflection Questions

- When you think about your research and teaching, what public issues do you see yourself ready to contribute solutions and education?

- After reviewing Figure 2, how are you using an array of mediums to share content? Where can you improve your efforts?

References

Allen, W.R., & Jewell, J.O. (2002). A Backward Glance Forward: Past, Present and Future Perspectives on Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The Review of Higher Education 25(3), 241-261. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2002.0007.

Balakrishnan, S. (2021). The Adult Learner in Higher Education: A Critical Review of Theories and Applications. In I. Management Association (Eds.), Research Anthology on Adult Education and the Development of Lifelong Learners (pp. 34-47). IGI Global. http://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8598-6.ch002.

Baughman, S., Boyd, H. H., & Franz, N. K. (2012). Non-formal educator use of evaluation results. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(3), 329-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.11.008.

Bonnen, J. T. (1998). The land grant idea and the evolving outreach university. In R. Lerner, & L. A. K. Simon (Eds.), University-Community Collaborations for the Twenty-First Century (pp. 25–70). Garland Publishing.

Cambridge, D., Kaplan, S., & Suter, V. (2005). Community of Practice Design Guide: A Step by-Step Guide for Designing & Cultivating Communities of Practice in Higher Education. EDUCAUSE. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2005/1/community-of-practice-design-guide-a-stepbystep-guide-for-designing-cultivating-communities-of-practice-in-higher-education.

Comer, M. M., Campbell, T., Edwards, K., & Hillison, J. (2006). Cooperative Extension and the 1890 land-grant institution: The real story. Journal of Extension, 44(3), Article 3FEA4. https://www.joe.org/joe/2006june/a4.php.

Coombs, P. (1976). Non-formal education: Myths, realities, and opportunities. Comparative Education Review, 20(3), 281-293. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1187481.

Crist, C., & Canales, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary program approach to building food and business skills for agricultural entrepreneurs. Journal of Extension, 58(3). https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol58/iss3/12.

DePauw, K. P, & McNamee, M. (2006). The new responsibility for state and land grant universities. In A. C. Nelson, B. L. Allen, & D. L. Trauger (Eds.), Toward a Resilient Metropolis. Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech.

Duemer, L. S. (2007). The agricultural education origins of the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862. American Educational History Journal, 34(1), 135–146. http://www.infoagepub.com/index.php?id=11&s=s4671eb77329b1.

Elliott-Engel, J. (2018). State Administrators’ Perceptions of the Environmental Challenges of Cooperative Extension and the 4-H Program and Their Resulting Adaptive Leadership Behaviors [Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech]. VTechWorks. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/98002.

Elliott-Engel, J., & Westfall-Rudd, D. (2018). Preparing future CALS professors for improved teaching: A qualitative evaluation of a cohort based program. NACTA Journal, 62(3), 229-236. https://www.nactateachers.org/index.php/volume-62-number-3-september-2018/2769-secondary-agriculture-science-teachers.

Elliott-Engel, J., Westfall-Rudd, D. M., Seibel, M., & Kaufman, E. (2020). Extension’s response to the change in public value: Considerations for ensuring the Cooperative Extension System’s financial security. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 8(2), 69-90. https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/868.

Etling, A. (1993). What is non-formal education? Journal of Agricultural Education, 34(4), 72-76. doi:10.5032/jae.1993.04072.

Farella, J., Hauser, M., Parrott, A., Moore, J. D., Penrod, M., & Elliott-Engel, J. (2021). 4-H Youth Development Programming in Indigenous Communities: A Critical Review of Cooperative Extension Literature. The Journal of Extension, 59(3), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.59.03.07.

Farella, J., Moore, J., Arias, J., & Elliott-Engel, J. (2021). Framing Indigenous Identity Inclusion in Positive Youth Development: Proclaimed Ignorance, Partial Vacuum, and the Peoplehood Model. Journal of Youth Development, 16(4), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2021.1059.

Fields, N. I. (2020). Exploring the 4-H Thriving Model: A Commentary Through an Equity Lens. Journal of Youth Development, 15(6), 171-194. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2020.1058.

Fordham, P. (1979) The interaction of formal and non-formal education. Studies in Adult Education, 11(1), 1-11. doi:10.1080/02660830.1979.11730384.

Ilvento, T. W. (1997). Expanding the role and function of the Extension system in the university setting. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 26, 153–165. doi:10.1017/S1068280500002628.

Jackson, D. G., & Johnson, L. (1999). When to look a gift horse in the mouth. Journal of Extension. 37(4), Article 4COM2. https://www.joe.org/joe/1999august/comm2.php.

Jones, G. E., & Garforth, C. (1997). The History, Development, and Future of Agricultural Extension. Improving Agricultural Extension: A Reference Manual. FAO.

Knoblauch, H. C., Law, E. M., & Meyer, W. P. (1962). State agricultural experiment stations: A history of research policy and procedure (No. 904). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Knowles, M. S., Swanson, R. A., & Holton, E. F. III (2005). The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development (6th ed.). Elsevier.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lee, G. G. (1963). The Morrill Act and education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 12(1), 19–40. doi:10.1080/00071005.1963.9973102.

Lee, J. M., & Keys, S. W. (2013). Land-grant but unequal: State one-to-one match funding for 1890 land-grant universities. APLU Office of Access and Success publication, (3000-PB1).

Meena, D. K., Meena, N. R., & Sharma, S. (2019). Fundamentals of Human Ethics and Agriculture Extension. Scientific Publishers.

Merriam, S. B. (2008). Adult learning theory for the twenty‐first century. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2008(119), 93-98. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.309.

Mississippi State University Extension Service. (2020). About Extension. Retrieved from: http://Extension.msstate.edu/about-Extension.

Morrill Land-Grant Act. (1862). U.S. Statutes at Large, 12 503.

Morse, G. W. (2009). Extension’s Money and Mission Crisis: The Minnesota response. iUniverse.

Okojie, M. C. P. O., & Sun, Y. (2020). Foundations of adult education, learning characteristics, and instructional strategies. In M. C. P. O. Okojie & T. C. Boulder (Eds). Handbook of Research on Adult Learning in Higher Education (pp. 1-33). IGI Global. https://www.igi-global.com/book/handbook-research-adult-learning-higher/232294.

Palmer, D. 2014. Boll Weevils and Beyond: Extension Entomology [Blog]. Retrieved from: http://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/ifascomm/2014/05/19/boll-weevils-and-beyond-Extension-entomology/.

Peters, S. J. (1996). Extension and the Democratic Promise of the Land Grant Idea. University of Minnesota Extension Service and Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs.

Provasnik, S., Shafer, L. L., & Snyder, T. D. (2004). Historically black colleges and universities, 1976-2001 (No. NCSE 2004 062). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Rasmussen, W. D. (1989). Taking the University to the People: Seventy-Five Years of Cooperative Extension. Iowa State University Press.

Redd, K. E. (1998). Historically black colleges and universities: Making a comeback. New Directions for Higher Education, 26(2), 33-43. doi:10.1002/he.10203.

Roebuck, J., & Murty, K. (1993). Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Their Place in American Higher Education. Praeger Publishers.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th Ed.). Simon and Schuster.

Rogers, E. M. (1988). The intellectual foundation and history of the agricultural Extension model. Science Communication, 9(4), 492–510. doi:10.1177/0164025988009004003.

Rosenberg, G. (2015). The 4-H Harvest: Sexuality and the State in Rural America. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Seevers, B., Graham, D., & Conklin, N. (2007). Education Through Cooperative Extension (2nd ed.). Delmar Publishers.

Selznick, P. (2011). TVA and the Grass Roots. Quid Pro Books.

Shinn, G. C., Wingenbach, G. J., Lindner, J. R., Briers, G. E., & Baker, M. (2009). Redefining agricultural and Extension education as a field of study: Consensus of fifteen engaged international scholars. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 16(1), 73-88. https://www.aiaee.org/attachments/101_Shinn-Redefining-Vol-16.1%20e-6.pdf.

Simon, J. Y. (1963). The politics of the Morrill Act. Agricultural History, 37(2), 103–111.

Smith-Lever of 1914, 7 U.S.C. 341 et. seq. (1914).

Stephenson, M. (2011). Conceiving land grant university community engagement as adaptive leadership. Higher Education, 61(1), 95–108. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9328-4.

Subramanian, K. R. (2018). Myth and mystery of shrinking attention span. International Journal of Trend in Research and Development, 5(1). http://www.ijtrd.com/papers/IJTRD16531.pdf.

U.S. Department of Agriculture-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA). (2015). The 1994 Land-Grant Institutions: Standing on Tradition, Embracing the Future. USDA- NIFA. https://nifa.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource/1994%20LGU%20Anniversary%20Pub%20WEB_0.pdf.

Vines, K. (2017). Engagement through Extension: Toward Understanding Meaning and Practiceamong Educators in Two State Extension Systems [Doctoral dissertation], The Pennsylvania State University. https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/catalog/13816kav11.

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

Wessel, T. R. & Wessel, M. (1982). 4-H: An American Idea, 1900–1980: A History of 4-H[USA]. National 4-H Council.

Whitacre, B. E. (2018). Extension’s role in bridging the broadband digital divide: focus on supply or demand? Journal of Extension, 46(3), Article 3RIB2. https://joe.org/joe/2008june/rb2.php.

Williamson, K. (2002). The beginning stages of research. In K. Williamson, A. Bow, F. Burstein, P. Darke, R. Harvey, G. Johanson, S. McKemmish, M. Oosthuizen, S. Saule, D. Schauder, G. Shanks, & K. Tanner (Eds.), In Topics in Australasian Library and Information Studies, Research Methods for Students, Academics and Professionals (2nd ed.), (pp. 49-66). Chandos Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-876938-42-0.50010-1.

Figure and Table Attributions

- Figure 10.1 Adapted under fair use from USDA NIFA 2019. Graphic by Kindred Grey.

- Figure 10.2 Kindred Grey. CC BY 4.0.

- Table 10.1 adapted from Balakrishnan, S. (2020). The adult learner in higher education: A critical review of theories and applications. In Accessibility and Diversity in the 21st Century University (pp. 250-263). IGI Global. doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-2783-2.ch013

- How to cite this book chapter: Elliott-Engel, J., Crist, C., and James, G. 2022. The Power of Extension: Research, Teaching, and Outreach for Broader Impacts. In: Westfall-Rudd, D., Vengrin, C., and Elliott-Engel, J. (eds.) Teaching in the University: Learning from Graduate Students and Early-Career Faculty. Blacksburg: Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. https://doi.org/10.21061/universityteaching License: CC BY-NC 4.0. ↵