11 Program Planning for Community Engagement and Broader Impacts

Jeremy Elliott-Engel; Courtney Crist; and Gordon Jones

Introduction

Good teaching in higher-education doesn’t solely occur in the formal classroom setting[1]. Thus, the objective of this chapter is to help graduate students and early career faculty to plan effective education in a community setting, particularly through Extension education efforts. While this chapter will discuss Extension programs it will be relevant for individuals who want to extend their research through community engagement to achieve broader impacts.

Extension educational programs can include both individual workshops and larger coordinated efforts that comprise a Program. Fordham (1979, p. 1) wrote “‘responding to needs’ as rapidly as possible is often the major justification for creating individual programs;” while there are many developments in praxis of program planning, this approach remains very common in practice (Gagnon et al., 2015). Yet, there is a risk of running from program to program —or need to need—as an Extension educator. If this is the educators method they will be busy and overwhelmed without any demonstrable impact (Arnold, 2015).

This chapter will discuss…

- The principles of program planning.

- Program planning factors including community needs and relationships.

- The principles of program planning in community context.

- How to make community impacts through research and teaching.

Any educator can succumb to the urge to respond in the moment and lose sight of the long-term goals. So, how does the Extension educator find intentional purpose and stay focused on the overarching goal? They plan.

The commonly accepted program planning model consists of six aspects (Cafarella, 2002; Cummings et al., 2015; Sork & Newman, 2004):

- Planning Table: Analyze planning context and client systems

- Needs assessment: Assess needs

- Logic modeling: Develop program objectives

- Formulate instructional plan: Prepare to teach across many modes

- Formulate administrative plan: Prepare to implement and utilize relationships to plan

- Evaluation: Design a program evaluation plan

It is important to note that while these steps are presented in a sequential order, they rarely occur linearly in practice (Arnold, 2015; Houle, 1996; Morell, 2010; Netting et al., 2008).

Analyze Planning Context and Client Systems

Extension educators, even more than classroom educators, need to understand the social and political context of their work. Extension educators conduct their work in local communities and engage with diverse and established ideals and knowledge. Understanding the political context of program delivery is important because, although community education work can increase political capital (Place et al., 2019), educators and the organization can also experience backlash (Elliott-Engel, Westfall-Rudd, Seibel et al., 2021). Recognition of the social context allows the educator to navigate appropriate partnerships and messaging. Further, each community and audience has cultural differences. The Extension educator must be sensitive to cultural differences in their many forms, not only differences in demographics, but also in language, religious affiliation and spiritual practice, values, and family and kinship patterns (Fields, 2020). The Extension educator must design and implement education that is responsive to these differences and engages these learners (Sork & Newman, 2004).

- A superb resource for in-depth guidance on program planning is the book Planning Programs for Adult Learners: A Practical Guide by Rosemary S. Caffarella and Sandra Ratcliff Daffron.

- An excellent resource for further reading is Working the Planning Table: Negotiating Democratically for Adult, Continuing, and Workplace Education by Ronald M. Cervero and Arthur L. Wilson.

- An excellent resource to explore social justice and societal context read Privilege, Power, and Difference by Allan G. Johnson.

Assess Needs

Training needs assessment is an ongoing process of gathering data to determine what training needs exist so that training can be developed to help the organization accomplish its objectives. … Often, organizations will develop and implement training without first conducting a needs analysis. These organizations run the risk of overdoing training, doing too little training, or missing the point completely. (Brown, 2002, p. 569).

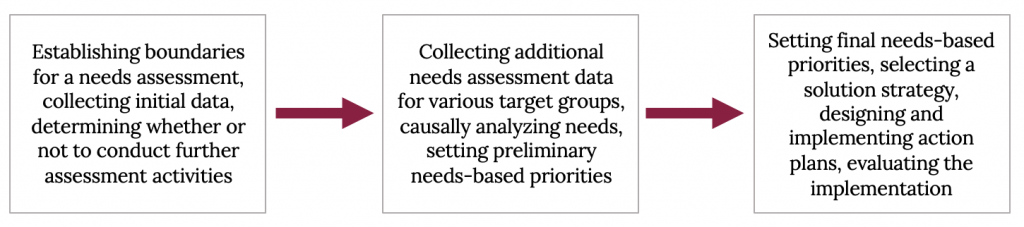

Once you are familiar with the planning context and client systems they will frame your ability to collect data in order to inform your understanding of your community needs. A needs assessment is essential to ensure the effectiveness of your Extension education efforts (Angima et al., 2014). Needs assessments are data driven and should help you identify gaps between current results and desired outcomes (for you and your community) and place the gaps in priority order (Kaufman et al., 1993).

To begin your needs assessment you must first establish what you want to know that will inform your educational program design. This will define the data collected. The data you collect can and, in many cases should, be wide ranging (e.g., Census or publicly available economic data, interviews with key stakeholders, surveys of your target clientele, focus groups, or even the photovoice method (Wang & Burris, 1997)). This data collection should be rigorous and theoretically informed (Arnold, 2015). Using a theory of behavior change (refer to Table 10.1 in Chapter 10) your needs assessment data should help you delineate what you can do to respond to the needs of your audience.

Make sure you maximize the effort you put into your needs assessment by publishing the process and/or the findings.

- For further reading on how to establish a strategic plan, refer to Strategic Planning Workbook for Nonprofit Organizations published by the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation.

- An excellent print resource for further reading and implementation is A Practical Guide to Needs Assessment by Kavita Gupta.

- Extension bulletins often cover needs assessment, such as Needs Assessment Guidebook for Extension Professionals by J. Donaldson and K. Franck or Methods for Conducting an Educational Needs Assessment by P. McCawley.

Develop Program Objectives

Using your needs assessment you now have established a direction for your Extension education efforts (McLaughlin & Jordan, 2004; Taylor-Powell, & Henert, 2008). There are two levels for you to consider when developing learning objectives: There is the macro level of identifying the long-term changes you are trying to accomplish, and there is the learning objective of each of your educational workshops. Unfortunately, in Extension education vernacular, both are called programs. The first occasionally are referred to as “Big P programs,” while the latter are often called “little p programs,” We will use these terms for this discussion.

Establishing objectives for your “Big P Program” takes on many of the characteristics of strategic planning. You will identify the long-term outcomes you want to see over time, and you will need to establish the many short-term goals necessary to accomplish these objectives. These plans should lead toward significant changes in society or in your organization (Elliott-Engel, Westfall-Rudd, & Corkins, 2021). These objectives are the overarching goals you have for your Extension work and will be the basis for all of your “little p programs.”

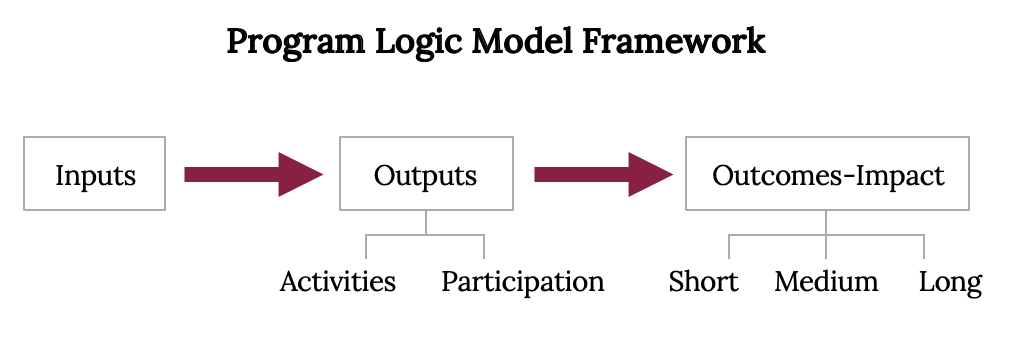

For your “little p programs,” Extension educators have adopted the use of logic models (Israel, 2001; Taylor-Powell & Henert, 2008). The logic model is a sequential causal relationship tool. It allows an educator to connect theory of change with the objectives sought. However, many program logic models are built on the “assumption that new knowledge leads to attitude change, which leads to behavior change” (Patton, 2008, p.108). The sometimes simplistic program plans developed in Extension, when they are developed at all, focus on creating change without considering the pervasive systems in which that change happens and the influence the system can have on whether changes take place (Arnold, 2015; Arnold & Nott, 2010; Patton, 2008). At worst, logic models are developed based on erroneous assumptions and unsound theory, which leaves the measurement of program outcomes incapable of demonstrating program impact.

Of course, as a new educator you do not want to replicate the shortcomings of those who have come before. To improve logic model utilization, it is important to first consider which outcomes you want to achieve, and then identify the inputs you will need and what outputs you will develop. These outputs are your objectives.

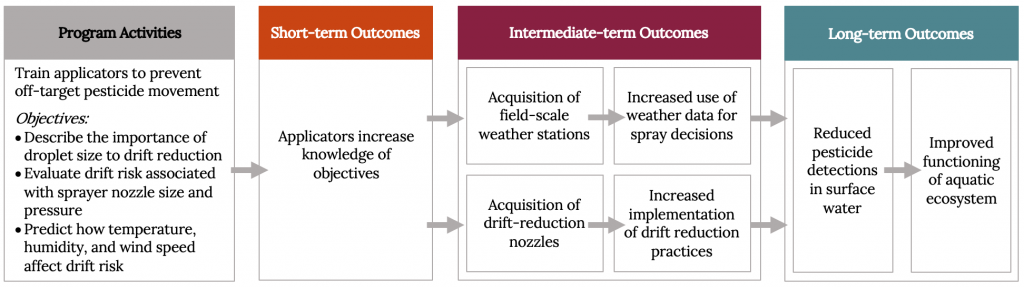

Figure 11.3 shows an example of a program logic model related to pesticide application techniques and drift prevention. In a watershed in southern Oregon, a group of agricultural professionals, local organizations with a focus on water quality, Oregon State University Extension Service, and concerned citizens engaged with the Oregon Departments of Agriculture and Environmental Quality to monitor streams in the watershed for pesticide contamination. The water quality results indicated some pesticides were likely drifting into surface water from air-blast applications to orchards and/or vineyards. In developing the logic model, we worked backward from the long-term goal of reduced pesticide detections and developed learning objectives targeting specific drift reduction mechanisms. We delivered both classroom and hands-on programs and shared print materials to provide a range of learning opportunities. Through our follow-up evaluations, we learned that many producers in the region have adopted the recommended strategies, and we await further water quality results to determine the real environmental impact of our program. Taylor-Powell & Henert (2008) is a great resource to help you develop your own logic model.

Syllabus Development

In a formal classroom setting there are many ways to bring nonformal education into the syllabus; these include adding a community education component to a group project (i.e., creating a YouTube video or social media graphic, or presenting to a community partner). Asking a learner to teach their content is an excellent way to demonstrate content knowledge, help expose gaps in knowledge, and build a deeper understanding. In addition, you could partner with local Extension educators across the state to help students see how the issues they are learning about in the classroom are being experienced in other communities, or to learn how people are addressing the issues. These approaches can help you develop and prepare educational materials to support your Extension education agenda, and can also help make a real-world connection to the class topic for the learner.

Formulate Instructional Plan

Now that you have long-term objectives and know how to connect those objectives to your long-range goals, what should you teach, and in what format? Formulating your instructional plan should start with your learners in mind. Who are your learners? What do you know about their knowledge on the topic? And, of course what educational goals do you want to accomplish?

Choosing what will be taught during a learning activity is a challenge because of time limitations, delivery modes, the varied backgrounds and experiences of the participants, materials available, and your own capability or style (Alessi & Trollip, 2001; Wlodkowski, 2008). To arrive at what is important, you can construct visual tools, such as a content map or outline. You can also talk it through with a colleague or knowledgeable stakeholder.

Caffarella and Daffron (2013, pp. 185-186) encourage the Extension educator to think about the following questions as they formulate the scope of the teaching:

- What content is essential for learners to know and does this content address one or more of the learning objectives?

- What is the content that learners should know, which supplements the essential material?

- What is the content that might be interesting and relevant to the essential materials, but will only be addressed as time allows?

- What is the content that learners do not need to know (that is, it may be useful but does not pertain to the learning objectives?

The above questions help the Extension educator set parameters of their content, just as a formal educator formulates a syllabus using similar objectives. Yet, the Extension educator also has to assess the framework for relaying the content. The Extension educator has many instructional techniques at their disposal. Earlier in the chapter, there was a discussion of the types of techniques the Extension educator will use to decide on which approach is most effective for learner knowledge change.

The Extension educator can ask themselves the following questions for clarity:

- What is your capability and preferred style of instruction? (e.g., your comfort facilitating)

- What learning environment is most effective for the learners’ characteristics? (e.g., different ways of knowing)

- What is the environment available to offer learning? (e.g., physical and virtual environments)

- What additional learning resources are available to me? (e.g., print, video, hands-on projects)

The nonformal learner should be valued for their possible contributions to the learning environment and co-creation of understanding and knowledge is an important assumption for the Extension educator. To do this the Extension educator will adopt teaching and learning opportunities that allow for knowledge transfer and discussion and opportunities to experience the phenomena being discussed (Moseley et al., 2019). Experiential learning is based on a theory of sociocultural experiences (table 11.1, refer to Kolb, Dewey, Piaget) and an educational philosophy which educators can adopt.

Experiential learning can be a challenge for any educator, including the Extension educator. As you try out new techniques it is important to engage the learners in the process to prevent discomfort by the instructor or the learner. For example, you can choose to inform the learners that you are trying new techniques and would welcome feedback on whether they worked. Feedback can also be solicited in the form of written responses to open-ended questions at the end of the session. This allows both learner and educator to reflect on the process and establishes both individuals as valuable to the process.

- A great resource on experiential learning is Learning through Experience: Troubling Orthodoxies and Intersecting Questions by Tara J. Fenwick.

- A great resource for specific tools for developing nonformal learning objectives is Planning Programs for Adult Learners: A Practical Guide by Rosemary S. Caffarella and Sandra Ratcliff Daffron.

Formulate an Administrative Plan

An administrative plan is the behind-the-scenes frame for how to execute your Extension education efforts. Finally, a conversation about the planning is needed for implementation. As always, the better the plan, the better the outcomes (Mehta & Mehta, 2018). An administrative plan involves recognizing your available time commitment (job description and appointments), budgets, and resources (e.g., personnel) needed to implement the plan.

Your Appointment and Job Description

Your appointment and job description will determine how much Extension education you will conduct in your role. Even faculty with zero Extension commitment, however, would be remiss if they did not ensure their research has value to the broader society, especially to Land Grant University (LGU) faculty. We only have so many hours in a day, and there are many demands on a faculty member’s time, so Extension education efforts must be planned with your other commitments from research and teaching in mind.

Extension efforts are, too often, an afterthought and are viewed as secondary or viewed as a second job on top of the teaching and/or research efforts. To be successful as a LGU faculty Extension education efforts should be embedded throughout your work and viewed as an important portion of your work to make a public impact. The more time and intentionality you invest in planning and informing your work with your needs assessment findings, the more likely you are to ensure your contribution to and impact on the stakeholders is maximized.

Funding Your Extension Education Work

In the higher education setting the ability to generate funding is increasingly important for professional success. No one will dispute that funding matters. It is important to keep in mind your big P objectives and little p opportunities when seeking funding. If you are clear about your goals, then you will be able to ensure grants are funding your efforts instead of your funding being your efforts. Being clear about what your audiences need and want is important as you seek funding to make your programs happen. First, you must know what your financial needs are to make your Extension education programming happen; second, you can discern what opportunities make sense to your goals; and third, you should think creatively about how a grant’s objectives intersect with your own. You will already be further ahead in your grant writing because you will have clear and well outlined objectives, informed by needs assessment data (that is hopefully published).

Increasingly, federal granting agencies discuss the term broader impacts (Donovan, 2019). Broader impacts are those short- and long-term impacts that our communities realize because of the research conducted. Extension education efforts are always a portion of the broader impact conversation, although it is rarely specifically mentioned despite the relationship between Cooperative Extension and the federal government. An LGU faculty is in a unique position to be supported in these efforts because of the Cooperative Extension expertise of the LGU, and the network of county-based professionals across the state.

Relationships

Relationships are important for your success. We have all heard about the value of networking for professional success. Relationships are important within academia and throughout the community. Relationships and networks are informed by power, and planning for education is a negotiation between power and knowledge. Thus, forming an administrative plan is not a quotidian task. Rather, it is fraught with critical decisions that will have implications for you and the people you choose to educate.

It will be important for you to think about the relationships that you build not only as social capital but as the opportunity to understand your educational context more effectively. Your relationships will be your access to new audiences and to ensure support for the programming you offer. These relationships will also inform the feedback you receive (Cervero & Wilson, 2001).

The relationship between county agents and campus-based Extension specialists is fundamental to the functioning of both an Extension service and the LGU model. In agriculture and natural resources, as in the other program areas, the system functions at its highest level when there is rich interconnection between field and campus faculty. County agents serve as the front line in identifying new challenges and opportunities facing agriculture, forestry, and other managed ecosystems. When those challenges and opportunities are beyond the technical or logistical capacity of agents, Extension specialists help to provide expertise, grant-writing, and research support to ensure that clientele are well served. When an unknown insect, disease, or nutritional deficiency begins to show up on farms or a new crop or technology takes hold in a region or state, the benefits of having a network of faculty and agents becomes clear. County faculty will have direct, personal connections with local producers, will be a valuable resource in identifying those emerging needs, and can form a vital network of research partners to validate or demonstrate new practices across the state. Extension specialists will oversee or conduct the applied research to answer new or lingering questions, lead the development resources and Extension programs, and serve as subject matter experts for county faculty to rely on. The back-and-forth collaboration between county agents and Extension specialists is a keystone in delivering helpful and impactful non-formal education and technical assistance to clientele.

County agents (this title varies by institution) are often the front line of Extension and the heartbeat of the county as they serve state stakeholders and communities. In the event a client has a need or question, in some state Extension systems they are encouraged to directly contact the county Extension office first instead of a subject matter expert or Extension specialist. For example, in the Extension program area of family and consumer sciences (FCS), as in the other areas, specialists answer stakeholder questions through agents. Additionally, programming ideas may be derived from agent experiences or common questions that are received at the office. In other words, agents often identify gaps in programming and agents and faculty may work together to develop programming. Some programming may have different categories (e.g., agent-delivered, agent-coordinated and specialist-delivered, specialist delivered). In agent-delivered programs, agents are often trained to deliver the content (inservice training). Agents select these programs from a program of work that they deliver over the course of a year. Programs may vary in their time, duration, and number of meetings.

The organizational structure of Cooperative Extension will vary by your LGU. To give you an example of how individuals across an LGU may work to support community education we share this example. At Mississippi State University specialists are expected to develop and manage at least one statewide program that agents may choose to offer in their counties. FCS, one of the core program areas, conducts programming that ranges from childhood development, finances, home economics, food safety, home food preservation, nutrition, exercise, etc. As an example, a home food preservation program was developed to serve state stakeholders when agents identified a gap in programming. Some agents have significant canning experience while others do not. While agents have the ability to conduct subject sessions in their county, only specialists can develop statewide programs; however agents can contribute and assist with the development. Home food preservation was developed in coordination with two county agents that have experience with home canning. The specialist(s) met with the agents to determine the sessions, lab activities, and program modules. Then the specialist developed the program and agents in the state pilot tested the program to work out content and guidance.

Feedback is very important for the success and execution of a program, especially when lab activities are involved. Once the program is finalized, agents will select the program (if interested) and attend inservice training (competency) to learn the content and lab activities (hands-on). Agents will then conduct the program in their county with their interested stakeholders. Generally, there is an evaluation piece to assess knowledge change and competency. In closing, agents are invaluable resources and are experts in their ability to extend knowledge. As a Specialist, it is important to make agents who have client questions a priority as they are the “face” of Extension. Agents are a vital part of the team and developing relationships and rapport with them is essential to success. Remember that agents want to see you and you should be involved.

No matter your area of expertise you will have varying levels of administration. For example, a county-based faculty member will have a County Director, and a Program Leader; a state level specialist will have a Department Head and a Program Leader. There may be other administrative structures depending on your university Extension organization (e.g., Regional Directors, Unit/Program leaders). Individuals in these administrative roles have the responsibility to inform you of your specific job duties, provide a supportive framework for your success, and serve as coach and mentor. Individuals in this role will help you navigate the many vagaries and pitfalls of the public interface and they should be viewed as a resource for program development. They have a different vantage point in the organization and may be able to connect you to your peers with similar work, or to other partners across the university, state, or country.

Keeping your administrators aware of your work is important—the more they know about what you are working on the more then can help you be successful. However, updating your administrators about your programming should be done succinctly and with respect for their time and role. More is not always better. Be judicious and respectful about time and place. No one likes a hard sell, and that strategy can backfire. Also, going above someone’s head without notification is rarely appreciated. Higher education is a bureaucracy and as such you should navigate through the chain of command, not because you could get what you want by jumping levels this one time, but because administrators in higher education are long-timers and building the relationships and following the organization norms will help you go farther for the long-term.

Partners

Our fast-changing world means that we cannot have all the answers; especially when it comes to solving problems, we must collaborate. In addition to making our resulting outcomes more effective, working as a team is just plain more fun, and the research shows if teams are more cognitively diverse, then they also arrive at better solutions (Aggarwal et al., 2019; Olson et al., 2007). Your partners should

- complement your areas of job performance weakness,

- bring new audiences to your program,

- bring new perspectives to your program,

- be responsible for the work they say they will do,

- be professionals who you respect, and

- be enjoyable to work with!

Your partnerships need to be authentic and reciprocal. Authentic partnerships are based on mutual respect and value for the person and organization even when there is no specific ask on the table. Reciprocal partnerships are based on mutual benefits. Do not confuse reciprocal with transactional (Burns, 1978). Reciprocity in successful partnerships is about working toward both parties’ best interests and being conscious about stewarding the relationship.

Partners are also important in maximizing impact (Bryson, 2004); they are important for your Extension education capacity to maximize your outreach, but also for many other aspects of your professional needs, not limited to grantsmanship and research. Partners have different networks and different vantage points, thus as you select the people you choose to call your team, do so with intentionality and care.

Balancing the Needs of So Many

There are different community scopes for Extension educators. Some educators view their workspace as encompassing both national and international reaches; others see their target community as a whole state; while yet others have a countywide or regional scope. No matter the size of the target community you will inevitably be pulled in too many directions, and without both a clear commitment to your overall objectives and an administrative plan you may very well find yourself going from problem to problem feeling very busy but not accomplishing much.

So, how do you find the right balance when there are so many demands? Your assessment of opportunities will need to be based on your overall Big P Program objectives and capacity for easy implementation of your little p. In theory this is easy to address, but it is incredibly hard to handle in practice. When you are certain of your objectives and your administrative plan you will have clear parameters to establish a framework for how to assess your ability to meet those needs. The framework will help you choose what opportunities you do want to get involved with or not when you are asked to take on an additional project. The framework rooted in your objectives and administrative plan will also give you language to explain why you are making this choice even as you are pushed and pulled by stakeholders, clientele, administrators, and funders and even as you become excited about the possibilities of other work.

As you balance the needs of so many people do not lose the forest for the trees. You will have a group of clients that become super users and will want a lot of your attention; this is a sign your program is valued. You will also want to ensure you are balancing the needs of both the many and the elite few high-profile clients. In a different instance of balancing service to different clients, we used the example of publishing. While publishing an article in a top-tier journal will be valuable for your promotion and tenure packet, if you have not also identified ways to ensure that new information is valuable to your community then you may have achieved one of your objectives, but you have lost sight of the long-range impacts of your work.

The concept of program integrity, defined as the degree to which a program is implemented as originally planned, is the core of your programming implementation. As described by Dane & Schneider (1998), program integrity consists of five main dimensions:

- Adherence refers to how closely program implementation matches operational expectations (Duerden & Witt, 2012).

- Dosage represents the amount of a provided service received by a participant (Duerden & Witt, 2012).

- Quality of delivery deals with the manner in which the service was provided (Dane & Schneider (1998).

- Participant responsiveness measures individuals’ engagement and involvement in the program (Domitrovich & Greenberg, 2000).

- Program differentiation identifies program components in order to ascertain their unique contributions to the outcomes (Dusenbury et al., 2003)

Diversity

Nonformal education program planning is about using intentional processes to ensure successful outcomes. Extension education is about extending the research-based information generated on campuses to community members. Therefore cross-cultural competency and understanding is fundamental to effective programming (Elliott-Engel, Westfall-Rudd, Seibel et al., 2021) and good program planning is essential. The Extension educator should be conscious of the many communities they are engaging with and take intentional steps to reduce barriers to information consumption (Intemann, 2009). Intentional interventions can include translating content and materials into appropriate languages in the communities they are reaching; ensuring graphics and other media are accessible to those with visual or hearing impairments; and tweaking program design to address the cultural characteristics of the communities you are working in (Farella et al., 2021). Extension educators also need to establish expectations within their programming to ensure a welcoming environment for all participants. Gonzalez et al. (2020) identify that to be inclusive, in their case LGBTQ+ youth, Extension educators will need to focus inclusion efforts at multiple levels, including: systemic advocacy, guidance and protocols, programming, and professional development and dispositions.

Bringing the Science to the People

Extension (both service and outreach) education connects research and teaching missions of the land-grant university to the citizens of the state. The Extension educator can, and should, serve as the conduit for not only your own research, but also that of others from campus. The larger your Extension education appointment the more likely you will be in a role of helping extend someone else’s research to the community. When others are conducting research or submitting grants, Extension educators can be brought in as key partners. You want to position yourself with faculty across campus in your role of expert—both in your content knowledge and your skills as a translational communicator.

Our universities are large bureaucracies, filled with many boundaries (or silos) between individuals. As Extension educators we should be trying to eliminate duplication of effort in extending research. Extension education work is translating research to the layperson, yet because individuals across our institutions are so often unaware of the land-grant mission, or the specifics of Extension, they end up reinventing the wheel. Do not recreate the wheel for extending knowledge. If you are an Extension educator, then keep up the advocacy for your mission and the value of the work you offer. Broader impacts are important, and Extension education can deliver these to communities across your state.

Also, as an Extension educator, Extension is the original open access content. Extension materials can be adapted, updated, and used with your new audiences. Of course, make sure you give attribution for the original work and make sure it is updated for your purposes.

Evaluation, Metrics, Defining Impact, and Use of Results

It will be no surprise to anyone that evaluation is an important aspect of your Extension program. Evaluation is often overlooked, yet it should be the foundation of your program planning. You will not be surprised to learn that evaluation is regularly viewed as a chore, an afterthought, or the follow-up work. This is unfortunately the case for far too many educators; Extension educators are not exempt despite a considerable focus on evaluation by administrators and in program-planning training. This section of the chapter will not teach you how to evaluate, but it will give you a framework to think about how to implement and use evaluation data.

By ensuring you have great learning experiences that are linked to learning outcomes, program conceptualization is the start of evaluation. Yet, Extension education has many different ways of measuring and conceptualizing impacts. While the Extension educator is of course interested in the learners’ knowledge change, there are also considerations for long-term behavior change, and the societal results when many individuals make similar changes.

In order to build support for Extension, “public value stories and statements” (Chazdon & Paine, 2014; Franz, 2013) or “public good” (Franz, 2011, 2013, 2015) are often used in place of the word “impact.” To measure indicators associated with impacts, an emphasis has been placed on evaluation (Cummings & Boleman, 2006; Franz et al., 2014). This is not a movement solely in Extension—it is also occurring across the public and not-for-profit sectors.

The impact on the individual learner is a private value. Private values (Lukes, 1973; Franz, 2011) are products and services that directly benefit private individuals and are consumed by those individuals. People typically access these products and services as paying customers in direct, voluntary economic exchanges. To evaluate private values, a pre- and post-survey strategy is effective at the point of delivery. Understanding learner knowledge change is the first evaluation building block. Follow-up to measure behavior change is needed after the training.

The impact on the broader community is a public value. Public value is consumed collectively by the citizenry rather than individually by clients or customers. It includes things that economists call “public goods” which are “jointly consumed,” “non-rivalrous,” and “non-excludable” (Donovan, 2019). This means that one person can consume them without reducing their availability to another person, and also that nobody is excluded from consuming them—for example,e public parks, clean air, and national defense (Alford & Hughes, 2008; Moore, 1995). Metrics to measure public value (Franz, 2013) are needed. To communicate public value effectively you will need to find metrics that connect the individual knowledge change to impact (Haskell et al., 2019; Place et al., 2019). It is not uncommon for knowledge change and outcomes to be connected only theoretically (see Logic Model; Travis et al., 2018).

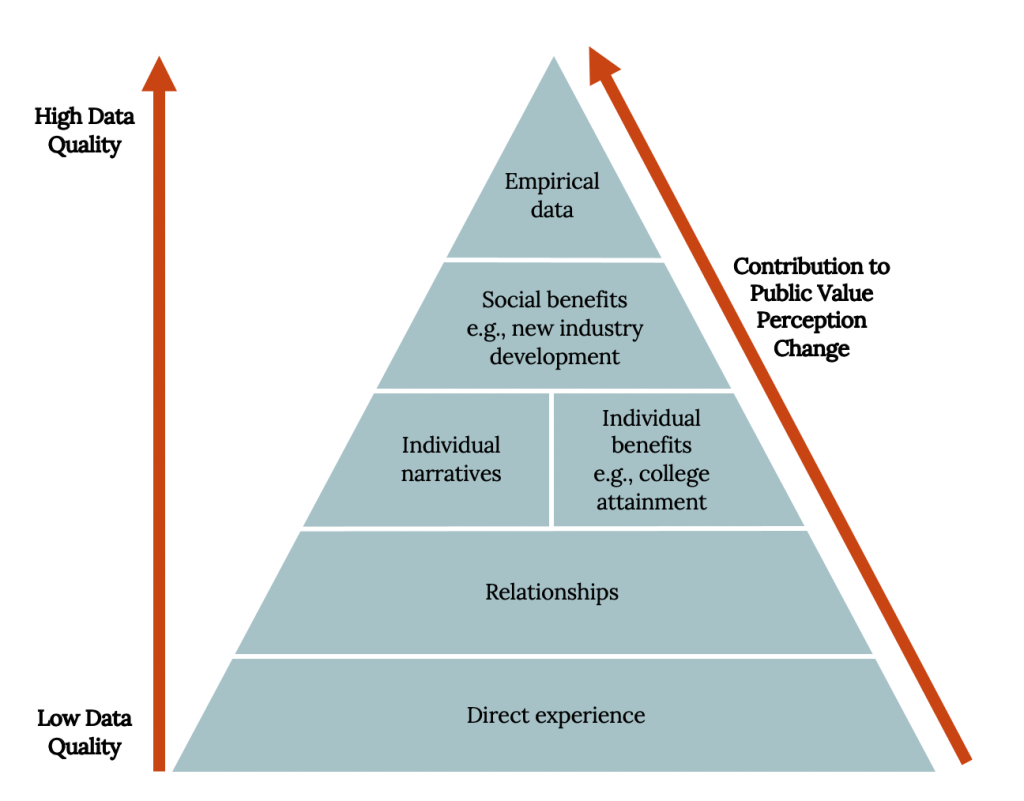

The data we collect implicates the perceived value of our Extension education efforts. Figure 11.4 highlights that both individual and public value data can support public value perception, yet for stakeholders (in this case government funders) public value is placed above individual experience and individual good.

Evaluation is important in communicating the “why” of your program to funders and stakeholders. Figure 11.4 illuminates the importance of empirical data for supporting the relevance argument. Yet, as an Extension educator you will need to critically assess your own programming using evaluation data to inform the effectiveness of a program. You can use these data to adapt your program to ensure goals are being met or you can choose to discontinue a program because you are not seeing the returns you would expect or the return on investment that makes it worth the expenditure of time or money.

Evaluation is a tool, one that should be embedded into your program model; the sooner you start incorporating an embedding evaluation into your program the more effective you will be. The quality of your program will increase, and you will be more able to share how and why your programming is valuable.

- An excellent resource for a deeper dive into program evaluation and assessment of public value is Program Evaluation Theory and Practice by Donna M. Mertens and Amy T. Wilson.

- An excellent resource for assessing learner outcomes is The Reflective Educator’s Guide to Classroom Research by Nancy Fichtman Dana and Diane Yendol-Hoppey.

- An excellent resource on understanding broader impacts is chapter 24, “Assessing the broader impacts of publicly funded research” by Claire Donovan in Handbook on Science and Public Policy.

Focused Excellence and Impact

After reading this chapter and this book, you may be completely overwhelmed with the many aspects of developing effective teaching, research, and Extension efforts. This is where your focused excellence comes in. Focused excellence is a framework for you to narrow, screen, and assess the many opportunities you are offered (Parrott et al., 2020). Only you can determine what your focused excellence will be, but your focused excellence should be the topic on which you want to be considered the expert, and the area you build support for through your research and Extension efforts. Focused excellence is targeted at a program in the Extension education context, such as childhood nutrition, 4-H youth civic engagement, or parasitic insects in livestock. These are examples of discrete categories that an Extension educator may choose as their area of focused excellence. Within this area you will use the program planning development model and establish focused objectives. To achieve focused excellence you will concentrate your attention on building depth and program quality in your programming rather than flitting from task to task and project to project. To achieve your own focused excellence you will develop strategies to maximize every effort for integrating research, teaching, and community education (a.k.a., Extension). The key to success is finding efficiency and optimizing opportunities to serve a dual role; this will not only benefit you, but will affect the impact and involvement of others. Extension education is a rewarding career path, where your work and effort directly impacts the community which you serve.

Reflection Questions

- Are you using an intentional program planning process in your community education efforts?

- Who are your current stakeholders and what feedback do you use to establish your research and teaching priorities?

- What do you do to maximize your efforts to spread your research to the community? And, how do you maintain focused excellence?

Resources

Barry, B. W. (1997). Strategic Planning Workbook for Nonprofit Organizations. Amherst H. Wilder Foundation.

Caffarella, R. S., & Daffron, S. R. (2013). Planning Programs for Adult Learners: A Practical Guide. John Wiley & Sons.

Dana, N. F., & Yendol-Hoppey, D. (2008). The Reflective Educator’s Guide to Professional Development: Coaching Inquiry-Oriented Learning Communities. Corwin Press.

Donaldson, J. L., & Franck, K. L. (2016). Needs Assessment Guidebook for Extension Professionals. UT Extension Publication. https://extension.tennessee.edu/eesd/PublishingImages/PB1839.pdf.

Donovan, C. (2019). Assessing the broader impacts of publicly funded research. In D. Simon, S. Kuhlman, J. Stamm, and W. Canzler (Eds.) Handbook on Science and Public Policy (pp. 488–501). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715946.00036.

Fenwick, T. J. (2003). Learning through Experience: Troubling Orthodoxies and Intersecting Questions. Krieger.

Gupta, K. (2011). A Practical Guide to Needs Assessment. John Wiley & Sons.

Mertens, D. M., & Wilson, A. T. (2018). Program Evaluation Theory and Practice. Guilford Publications.

Taylor-Powell, E., & Henert, E. (2008). Developing a logic model: Teaching and training guide. Benefits, 3(22), 1-118. https://ou-webserver01.alaska.edu/ianre/internal/reporting/logicmodel/logicmodeltrainingguide.pdf

References

Aggarwal, I., Woolley, A. W., Chabris, C. F., & Malone, T. W. (2019). The impact of cognitive style diversity on implicit learning in teams. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 112. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00112.

Alessi, S. M., & Trollip, S. R. (2001). Multimedia for Learning: Methods and Development (3rd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Alford, J., & Hughes, O. (2008). Public value pragmatism as the next phase of public management. The American Review of Public Administration, 38(2), 130-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008314203.

Angima, S., Etuk, L., & King, D. (2014). Using Needs Assessment as a Tool to Strengthen Funding Proposals. The Journal of Extension, 52(6), Article 33. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol52/iss6/33.

Arnold, M. E. (2015). Connecting the dots: Improving Extension program planning with program umbrella models. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 3(2). https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/685.

Arnold, M. E., & Nott, B. D. (2010). What’s going on? Developing program theory for evaluation. Journal of Youth Development, 5(2), 71-82. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2010.222.

Brown, J. (2002). Training needs assessment: A must for developing an effective training program. Public personnel management, 31(4), 569-578. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102600203100412.

Bryson, J. M. (2004). What to do when stakeholders matter: stakeholder identification and analysis techniques. Public management review, 6(1), 21-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030410001675722.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row.

Caffarella, R. S. (2002). Planning Programs for Adult Learners: A Practical Guide For Educators, Trainers, and Staff Developers (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Caffarella, R. S., & Daffron, S. R. (2013). Planning Programs for Adult Learners: A Practical Guide. Wiley & Sons.

Cervero, R. M., & Wilson, A. L. (2001). Power in Practice: Adult Education and the Struggle for Knowledge and Power in Society. John Wiley & Sons.

Chazdon, S. A., & Paine, N. (2014). Evaluating for public value: Clarifying the relationship between public value and program evaluation. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 2(2). https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/670.

Cummings, S. R., Andrews, K. B., Weber, K. M., & Postert, B. (2015). Developing Extension professionals to develop Extension programs: A case study for the changing face of Extension. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 3(2), 132-155. https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/689/593.

Cummings, S. R., & Boleman, C. T. (2006). We identified issues through stakeholder input: Now what? The Journal of Extension, 44(1), Article 1TOT1. https://www.joe.org/joe/2006february/tt1.php.

Dane, A. V., & Schneider, B. H. (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review, 18(1), 23-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00043-3.

Domitrovich, C. E., & Greenberg, M. T. (2000). The study of implementation: Current findings from effective programs that prevent mental disorders in school-aged children. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 11(2), 193-221. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532768XJEPC1102_04.

Donovan, C. (2019). Assessing the broader impacts of publicly funded research. In D. Simon, S. Kuhlman, J. Stamm, and W. Canzler (Eds.) Handbook on Science and Public Policy (pp. 488–501). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715946.00036.

Duerden, M. D., & Witt, P. A. (2012). Assessing Program Implementation: What It Is, Why It’s Important, and How to Do It. The Journal of Extension, 50(1), Article 5. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol50/iss1/5.

Dusenbury, L., Brannigan, R., Falco, M., & Hansen, W. B. (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research, 18(2), 237-256. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/18.2.237.

Elliott-Engel, J. (2018). State Administrators’ Perceptions of the Environmental Challenges of Cooperative Extension and the 4-H Program and Their Resulting Adaptive Leadership Behaviors (Doctoral dissertation), Virginia Tech. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/98002.

Elliott-Engel, J., Westfall-Rudd, D. M., Seibel, M., & Kaufman, E. (2020). Extension’s response to the change in public value: Considerations for ensuring financial security for the Cooperative Extension System. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 8(2), 69-90. https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/868.

Elliott-Engel, J., Westfall-Rudd, D., & Corkins, C. (2021). Engaging Stakeholders in Extension Strategic Planning. The Journal of Extension, 59(4), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.59.04.03.

Elliott-Engel, J., Westfall-Rudd, D., Kaufman, E., Seibel, M., & Radhakrishna, R. (2021). A Case of Shifting Focus Friction: Extension Directors and State 4-H Program Leaders’ Perspectives on 4-H LGBTQ+ Inclusion. The Journal of Extension, 59(4), Article 14. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.59.04.14

Elliott-Engel, J., Westfall-Rudd, D. M., Seibel, M., Kaufman, E., & Radhakrishna, R. (2021). Extension administrators’ perspectives on employee competencies and characteristics. Journal of Extension, 59(3), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.59.03.03.

Farella, J., Moore, J., Arias, J., & Elliott-Engel, J. (2021). Framing Indigenous Identity Inclusion in Positive Youth Development: Proclaimed Ignorance, Partial Vacuum, and the Peoplehood Model. Journal of Youth Development, 16(4), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2021.1059.

Fields, N. (2020). Exploring the 4-H thriving model: A commentary through an equity lens. Journal of Youth Development, 15(6), 171-194. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2020.1058.

Fordham, P. (1979). The interaction of formal and non-formal education. Studies in Adult Education, 11(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.1979.11730384.

Franz, N. K. (2011). Advancing the public value movement: Sustaining Extension during tough times. Journal of Extension, 49(2), Article v49-2comm2. https://www.joe.org/joe/2011april/comm2.php.

Franz, N. K. (2013). Improving Extension programs: Putting public value stories and statements to work. Journal of Extension, 51(3), Article 9. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol51/iss3/9/.

Franz, N. K. (2015). Programming for the public good: Ensuring public value through the Extension Program Development Model. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 3(2), 13. http://media.wix.com/ugd/c8fe6e_7c4d46d779db4132943d4fae8f1d9021.pdf.

Franz, N. K., Arnold, M., & Baughman, S. (2014). The Role of Evaluation in Determining the Public Value of Extension. The Journal of Extension, 52(4), Article 32. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol52/iss4/32.

Gagnon, R., Franz, N., Garst, B. A., & Bumpus, M. F. (2015). Factors impacting program delivery: The importance of implementation research in Extension. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 3(2), 68–82. https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/686.

Gonzalez, M., White, A. J., Vega, L., Howard, J., Kokozos, M., & Soule, K. E. (2021). “Making the Best Better” for Youths: Cultivating LGBTQ+ Inclusion in 4-H. The Journal of Extension, 58(4), Article 3. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol58/iss4/3.

Haskell, J. E., Baker, B. A., Olfert, M. D., Colby, S. E., Franzen-Castle, L. D., Kattlemann, K. K., & White, A. A. (2019). Using ripple effects maps to identify story threads: A framework to link private to public value. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 7(3), 1-23. https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/899.

Houle, C. O. (1996). The Design of Education. Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. Jossey-Bass.

Intemann, K. (2009). Why diversity matters: Understanding and applying the diversity component of the National Science Foundation’s broader impacts criterion. Social Epistemology, 23(3-4), 249-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691720903364134.

Israel, G. D. (2001). Using Logic Models for Program Development. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, EDIS.

Kaufman, R. A., Rojas, A. M., & Mayer, H. (1993). Needs Assessment: A User’s Guide. Educational Technology.

Lukes, S. (1973) Individualism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

McLaughlin, J. A., & Jordan, G. B. (2004). Using Logic Models. Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, p. 7-32. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, J. S. Wholey, H. P. Hatry, & K. E. Newcomer (Eds.). Jossey-Bass.

Mehta, A., & Mehta, N. (2018). Knowledge integration and team effectiveness: A team goal orientation approach. Decision Sciences, 49(3), 445-486. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12280.

Moore, M. (1995). Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Harvard University Press.

Morell, J. A. (2010). Evaluation in the Face of Uncertainty: Anticipating Surprise and Responding to the Inevitable. Guilford Press.

Moseley, C., Summerford, H., Paschke, M., Parks, C., & Utley, J. (2019). Road to collaboration: Experiential learning theory as a framework for environmental education program development. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 19(3), 238-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533015X.2019.1582375.

Netting, F. E., O’Connor, M. K., & Fauri, D. P. (2008). Comparative Approaches to Program Planning. John Wiley & Sons.

Olson, B. J., Parayitam, S., & Bao, Y. (2007). Strategic decision making: The effects of cognitive diversity, conflict, and trust on decision outcomes. Journal of Management, 33(2), 196-222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306298657.

Parrott, A., Hauser, M., & Farella, J. (2020). Applying Focused Excellence: The Program Area Framework [Unpublished Extension Publication]. Arizona Cooperative Extension, The University of Arizona.

Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilization-Focused Evaluation. Sage.

Place, N. T., Klemme, R. M., McKinnie, M. R., Baker, C., Parrella, J., & Cummings, S. R. (2019). Credible and actionable evidence across stakeholder levels of the Cooperative Extension System. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 7(2), 124-143. https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/827.

Sork, T. J., & Newman, M. (2004). Program development in adult education and training. In G. Foley (Ed.), Dimensions of Adult Learning: Adult education and Training in the Global Era (pp. 96-117). Open University Press.

Taylor-Powell, E., & Henert, E. (2008). Developing a Logic Model: Teaching and Training Guide. University of Wisconsin Extension, Cooperative Extension, Program Development and Evaluation. https://fyi.Extension.wisc.edu/programdevelopment/files/2016/03/lmguidecomplete.pdf.

Travis, E., Alwang, A., & Elliott-Engel, J. (2018). Developing a Holistic Assessment for Land Grant University Economic Impact Studies: A Case Study. In 2018 Annual Meeting of the Southern Agricultural Economics Association, Jacksonville, Florida (No. 266789). https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.266789.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309.

Wlodkowski, R. J. (2008). Enhancing Adult Motivation to Learn: A Comprehensive Guide for Teaching All Adults (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Figure and Table Attributions

- Figure 11.1 Adapted under fair use from From Needs Assessment to Action: Transforming Needs into Solution Strategies, by J. W. Altschud and B. Witkins, 2000, Sage. Graphic by Kindred Grey.

- Figure 11.2 Adapted under fair use from Taylor-Powell, E., & Henert, E. (2008). Developing a Logic Model: Teaching and Training Guide. University of Wisconsin Extension, Cooperative Extension, Program Development and Evaluation. https://fyi.Extension.wisc.edu/programdevelopment/files/2016/03/lmguidecomplete.pdf. Graphic by Kindred Grey.

- Figure 11.3 Kindred Grey. CC BY 4.0.

- Figure 11.4 Adapted under fair use from Figure 1.0 in Elliott-Engel et al. (2020). Extension’s response to the change in public value: Considerations for ensuring the Cooperative Extension System’s financial security. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 8(2), 69-90. https://www.jhseonline.com/article/view/868. Graphic by Kindred Grey.

- How to cite this book chapter: Elliott-Engel, J., Crist, C., and James, G. 2022. Program Planning for Community Engagement and Broader Impacts. In: Westfall-Rudd, D., Vengrin, C., and Elliott-Engel, J. (eds.) Teaching in the University: Learning from Graduate Students and Early-Career Faculty. Blacksburg: Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. https://doi.org/10.21061/universityteaching License: CC BY-NC 4.0. ↵