6 Fun Fridays: Incorporating Hands-on Learning into Lecture Courses

Bethany Wolters

Introduction

If you observe a traditional lecture class, it will be the teacher who is most physically and mentally active and engaged, not the students[1]. In a class with hands-on learning, you will see students being involved in their own education by debating a case study in small groups or using a reference manual to solve a problem. Hands-on learning happens when the action that takes place in the classroom is done by the students rather than the teacher. Hands-on learning does not require physical movement, but it requires an active mind, similar to how a chess player will plan the next few moves in their head before reaching out to move their piece (Barkley, 2020). Laboratory, field, and studio classes use hands-on learning to teach concepts and develop skills, but hands-on learning can also be used in lecture courses.

Hands-on learning in lecture classes can reinforce student learning and enhance the understanding of course content, and is often more interesting than lectures. The benefits of hands-on learning activities in class are greater student motivation to learn, a sense of community in the classroom, (often) higher grades, more student confidence while learning new things, and development of teamwork and soft skills that they would not practice in a lecture (Deslauriers et al., 2019; Svincki & Mckeachie, 2014). Having students perform a task, practice a skill, or solve a problem prevents the “illusion of understanding” that can happen when listening passively to lectures and taking notes (Svincki & Mckeachie, 2014). As more universities choose to remove lab sections from applied science courses due to a lack of funding, space, and personnel, hands-on learning can provide the essential skills to help students prepare for future careers.

This chapter about hands-on learning was written with knowledge gained through the first-hand experience teaching with hands-on learning. Hands-on learning was used in an upper-level Soil Fertility class every Friday, during “Fun Fridays.” The only rule for Fun Fridays was no lecture. Instead, the class members explored soil fertility concepts and skills through workshops, case studies, discussions, and other activities in a traditional college classroom with rows of desks, blackboards, and a projector. The stories and lessons from the Fun Friday classes in Soil Fertility course will help you prepare for hands-on learning before the semester starts, facilitate effective hands-on lessons and highlight potential challenges with hands-on learning.

This chapter will discuss…

- The benefits of using hands-on learning in traditionally lecture-based courses.

- How to prepare, develop, facilitate and assess hands-on learning.

- The potential challenges of using hands-on learning in the classroom and how to meet those challenges.

Preparing for Hands-On Teaching

Preparation is even more critical for hands-on learning than it is for lecture-based learning because once you give it to students, you’re mostly out of the picture. A little thought and preparation will go a long way toward making both the hands-on activities and your overall class successful and help students learn. You can prepare by identifying elements to teach through hands-on learning, creating lesson plans and considering incorporating active-learning overall course structure.

Finding hands-on learning topics

Students learn skills best through hands-on practice. Hands-on learning can also teach students about concepts and theories by showing rather than telling. It is all right if you are not sure exactly how you will use hands-on learning to teach these topics because as you start developing lesson plans and preparing for class, ideas and inspiration are likely to come to you.

Lecture-based classes tend to focus on “knowing” content. To guide your development of hands-on learning, instead of asking yourself, “What do my students need to know?,” ask these questions about your course content:

- What do I want my students to be able to do?

- What information or tools do I think my students need to be able to find or use?

- What products or performances do students need to be able to create and present?

- What decisions do my students need to be able to make?

- Are there any scenarios, simulations, or experiments that demonstrate the principles students need to know?

- What are the issues or discussions in this field that my students need to be aware of?

- What lessons from the history of my field can my students and I learn from this story?

The answer to the first four questions will be specific tasks or activities that will likely be both the learning objective and that lesson’s activity. The last three questions can help you develop hands-on learning for topics that do not have immediate applications. The hands-on element comes when students must form their arguments, opinions or reach their own decisions about simulated or real situations. Story-telling elements of case studies or historical events can also make learning more engaging. For example, in Soil Fertility, students learned about urban soil contamination sources and how organic matter can be used to remediate soils through a case study about an urban community garden in a food desert (Harms et al., 2014). Combining the answers to these questions with learning objectives will give you the overall plan for your hands-on learning lesson.

Placing hands-on learning within your course

The second most important decision is how and when hands-on learning will happen in your course. This decision needs to be made early in the course design process because it impacts scheduling, assignments, grading, and course policies. You should carefully consider details like how much time there is for activities in each class period, the arrangement of chairs and tables in the room, and the number and size of student groups.

Hands-on activity lesson planning needs to happen with the overall course lesson plan in mind. Will you use hands-on learning in every class period or once or twice a week? Will there be in-class lectures or a flipped classroom, with lectures or readings outside of class? In Soil Fertility, hands-on learning happened once a week, on Fridays. When you consider the placement of the activity within the semester, ensure sufficient scaffolding around hands-on learning activities. Hands-on learning activities can reintroduce and reinforce content from lectures and assigned readings earlier in the week or can be used to introduce a concept in preparation for readings and lectures. In some situations, the hands-on learning activity may stand alone without any additional instruction, but this is rare and is not appropriate for the most crucial course concepts.

How much time things will take and how much content to cover is hard to answer if you have never taught the material in a hands-on learning lesson. A general rule you can use is to assume an activity will take twice as long as you expect it to take. After you have taught an exercise once, you will be better able to gauge how much time it will take in the future. Until then, have a general plan for how you might shorten the activity or lesson by a few minutes if it is running long. You could plan an alternative ending activity, reduce the closing debrief section, or allow students to finish the remaining work at home and submit it in an alternative manner. Another option is to complete the activity in the next class period or provide a video, hand-out, or reading that allows students to learn the remaining content at home. You should also plan to have extra activities or content if the activity goes faster than expected or for students who finish more quickly than their classmates. Prepare about 25% additional content or activities that you don’t think you will realistically finish. The supplementary material is useful for extra practice problems or future assessments if you don’t use it in class. Individual self-paced activities, as opposed to group assignments, are more time flexible. Students who finish quickly can leave, but students who take more time or need more help can continue working without pressure to keep up.

The way hands-on learning will be graded and how it contributes to the final course grade will influence how well it works. It might seem that grading hands-on learning will detract from the value of learning in hands-on lessons, but it helps students buy into the experience. Emphasize the importance you place on hands-on learning in a context that the students will understand: grades. Imagine that your students are your employees, and you pay them in points toward their final grades in exchange for class activities and assignments. They will prioritize what you value, and grades communicate to students what you view as valuable. When calculating the total grade proportion from hands-on learning, consider the amount of in-person class time you will spend on hands-on learning, both in-class and out of class, and the amount of time needed for other class activities. Making hands-on learning worth as much or more than more traditional assessments communicates to students that you want this to be important in this class. Hands-on learning activities can be graded based on participation or correctness, or some combination. When hands-on learning is graded based on attendance and participation in hands-on activities, there are no grades attached to the quality or accuracy of students’ products or work. Grading for participation and engagement, rather than correctness, lowers the stakes for students uncertain about hands-on learning, allows you to give them more challenging activities, and often does not require as much effort to grade. It also lowers the stakes and provides more flexibility to you, as the teacher, if new hands-on lessons do not go as intended or expected. But you will need to use other assessments to assess their knowledge and skills. The other option is to grade the accuracy and quality of products created by students during hands-on learning. If you do this, you need to provide sufficient time, resources, and instruction for students to feel like they can be successful. Either follow the same grading criteria every week or clearly communicate your expectations at the start of each activity.

Finally, think about the logistics of how hands-on learning will work in your specific classroom. Evaluate and decide how to use group work; use the chairs, table, and space within the physical classroom; and what other resources you will need. Hands-on learning can be done individually, in small groups, or in some situations as an entire class. Groups can be self-selected or assigned, permanent or flexible, and each has pros and cons. It is easy to switch between individual and group work throughout the semester, but it is easier to form groups, in the same way, all semester long. The physical arrangement of your room has a significant impact on the amount of active learning that can happen. But don’t let traditional lecture room set-ups stop you from using active learning in your class. If possible, move the furniture or allow students to spread out throughout the entire space (sitting on the floor or auditorium stage, or in the aisles). You can also utilize virtual spaces to collaborate when a physical setting does not easily allow it. What technology and tools will you use in hands-on learning? Students can work on physical paper hand-outs and refer to reference books, or they could be collaboratively working on a class document and referring to web resources. Students need to know at the beginning of the semester and before each hands-on learning class, what technology they will need to bring to participate.

Diversity

Hands-on learning can be more inclusive of diverse student learning modes and levels of experience. However, it is not inclusive of students that need to be absent from classes for excused (student-athletes, student contents, and competitions, field trips, or conferences) or unexcused (illness, emergency, or choice) reasons. Instead of trying to replicate the in-class experience, design alternative activities that can be completed individually but incorporate some of the same hands-on elements. Examples of alternative hands-on assignments I used were attending guest lectures and seminars, designing an infographic, or writing a reflection of how the course connects to the conference or job interview. Alternative assignments can also help students who are not comfortable sharing their reasons for being absent.

Writing lesson plans

The last step in preparing to teach hands-on learning lessons is to create a lesson plan and design the activity. There are many ways to develop lesson plans, so find a template or system that works for you. Sections useful to include in your lesson plan are lesson learning objectives, pre-class activities (if applicable), list of materials needed, digital or physical resources used by teacher or students, activity logistics (group size and set-up, timing), activity introduction and closing.

Now create hands-on learning activities. Instead of preparing a lecture and selecting readings, you will be making the problem or task students will complete and gathering or creating resources and tools for them to use. For a case study or topic discussion lesson, clearly define the problem, and collect resources that provide background and information. In a mathematical workshop lesson, write out the example and practice problems with solutions. For simulations or role-playing lessons, create realistic scenarios, stories, and artifacts for students to engage with as they try to solve the problem. To create an experiment or simulation, you need to gather or create the materials or data that students will manipulate during the activity. For both realism and to save time and effort, try to use real data or information and adapt it to your lesson. If actual data is not available, you can create it. Researchers and practitioners in the field are an invaluable source for scenarios, data, or examples. After you create the activity’s content, you need to make the hand-outs, questions, or assignments that students use during the activity.

Before Getting to the Classroom

Students are often excited about hands-on learning but apprehensive because they don’t know what to expect. You can help ease students’ fears by being clear on what they can expect to happen and your expectations for them during the hands-on learning classes. Try to have the first hands-on learning lesson as soon in the semester as possible. The first hands-on learning lesson can be related to the class or it can be a creative problem-solving or group project.

For some or all hands-on learning lessons, pre-class instruction in or out of class might be necessary to allow enough class time to complete the activity. Anything that takes more than 5 minutes in a 50-minute class or 10 minutes in a more extended class to teach to students should be completed before class to allow enough time for the hands-on activity. However, you then need to have a way to hold students accountable for completing the pre-class instruction.

Syllabus Development

Use your syllabus to communicate to students the value you place on hands-on learning through the course grading. If hands-on learning is used regularly in the course, it would not be inappropriate to weigh it equal to or higher than a midterm or final exam.

In the Classroom

Hands-on learning will look different in every classroom because of the people involved, size of the class, size and arrangement of the room, and length of each class period. In Soil Fertility, hands-on learning took place in a traditional lecture classroom on one of the three 50 minute class periods per week. The class time was spent with a 5- to 10-minute opening, a 20- to 30-minute activity and a 5- to 15-minute closing. This setup might be very similar to what most of your classes and classrooms look like too, but you can extrapolate this discussion to fit your specific class format. While each hands-on learning lesson will look different, it helps follow a similar format so students know what to expect. A 50-minute class period is almost too little time to do a hands-on learning lesson well, and a 75-min class session would likely work better.

At the beginning of class

At the beginning of each class, you will introduce the activity and provide instructions. This part of the hands-on learning is the most crucial for the activity’s success, so ensure appropriate time. Give a short (~5 minutes) introduction to the subject or skills being covered in the activity and show how the activity connects to other course topics. Give all instructions verbally while also showing written instructions on the screen or in a handout for students. Explain all the instructions or background that are essential for completing the activity. For example, when doing a case study, provide students the text of the case and give a verbal summary of important points.

Next, explain the logistics of the activity in terms as clear and precise as possible. Give instructions on student collaboration, group size, and group assignments if this has not already been established in your course. Show students where to find and how to use all of the resources or tools you provide. Explain what the goal of the activity is and how to use any worksheets or handouts. Let students know how much time they will have to complete all or parts of the activity. Last, explain to students what their end product should be, how it will be turned in, and how it will be graded. If your grading method or criteria varies from week to week, be clear about your expectations before they begin. It is advantageous to make sure that students have a copy of these instructions to refer to throughout the entire activity, either on the screen, or as a digital copy or a handout. Then, you turn them loose to do hands-on learning for themselves!

During the hands-on activity

The first five minutes of hands-on learning activity is the most difficult for the teacher because, at this point, you’ve relinquished the control. Give students some time and space at the beginning of the activity and while they are working.

If you feel like you should be doing something, here are some things you can do instead of hovering over the students:

- Drink your coffee, tea, or water (hydration is important but so hard while you are talking!).

- Organize papers students turned in, or that you have to return to students.

- Answer that urgent email/text from your advisor/student/boss/spouse/roommate.

- Enjoy a few minutes to yourself.

- Watch the students work (without too much awkward staring), and you can learn a lot about how they are working together, group logistics, what parts of the project need work.

- Make sure you have the answer or solution to the hands-on activity worked out and written down (if you haven’t already).

- Take attendance.

While giving students space to work, be aware of students who have questions, and be accessible. After giving students some time to get started on the activity, you can begin circulating through the classroom and quickly check in. Stop by groups or individuals and ask, “How are things going?”, “Have you found X yet?” or even personal questions like “How has your week been?” if it won’t interfere with the flow of their work too much. Sometimes asking if students have questions can limit the discussion between you and students and steer it toward problems rather than exploring interesting ideas. Try to learn students’ names and address them by name while checking in with students. Sometimes, a student or group needs a minute to formulate or remember a question they have to ask you, so it can help to plan to spend a minute or two with the group before moving to the next group.

While checking-in with students, you will be able to identify groups who are struggling. Groups may be struggling with group dynamics and teamwork or understanding the concept or a step in the activity. One thing you can do is ask if they would like you to join their group for a few minutes. For group dynamic problems, you may propose a new division of labor or try to mediate any issues. Unless teamwork is one of your learning objectives, it is ok to allow dysfunctional groups to work individually or join other groups. Even if you know what the problem is and how to fix it, try to ask questions that will guide them to what might be causing the problem. Let the student run student-centered learning, so try not to get in the way. This is one of the hardest things to do and requires developing a comfort level with mistakes and inefficiencies that happen during the learning process. The goal is to get the group or individual to a place where they can continue working on their own, and you can check back in after a few minutes to make sure they’re making progress.

Closing out the class

As much as possible, stay on schedule so that you have time to debrief the activity and close the class. To conclude the activity, you can choose to review answers, collect student work, or hear reports from some or all of the small groups. Other options include a whole-class discussion, soliciting questions or feedback from students, or offering your concluding thoughts. Be clear about what students should have learned from the activity and what they will need to know for assignments and exams. If you run out of time, you can transfer some or all of the closing activities online or finish them in the next class period.

How to rescue a disaster

First, don’t beat yourself up about hands-on learning activities that fall apart. An essential part of the hands-on learning process you are encouraging students to be a part of involves failures or mistakes, reevaluating, and trying again. You probably don’t expect your students to get everything right the first time, so don’t be surprised when you don’t either. Students will be more willing to try and possibly fail if they see their teacher model learning from failure. Use your mistakes as a way for you to learn and grow your teaching.

Second, don’t lie. Just tell your students the activity did not work out as you expected. They probably already know it didn’t work. Instead, talk with your students about what you hoped they would get out of the activity and why you made the decisions (logistical or content-related) that you did. You may choose to invite the students’ feedback on why something didn’t work, their knowledge or impressions, or their suggestions. And if possible, you can try to connect or tie in the results of the less than perfect hands-on learning activity to your topic, your class, or being a responsible citizen in the world and your field.

Hands-on Lessons about Hands-on Learning

New things are uncomfortable for everyone

When you first start using hands-on learning, it will be awkward and uncomfortable for everyone. As a teacher, the first few classes and the first semester will be challenging for you and the students. But it will get easier. Here are some things you can do to ease the transition:

- Be positive and authentically enthusiastic about the activities. Your tone and attitude set the stage for the class.

- Start active learning early in the course and do it regularly and often.

- Do not accept anything less than the expectations you outlined for students in terms of participating and engagement. You do not have to be mean, but you may have to be stern for the first few weeks. If students sense that they can get away with not participating, their behaviors may continue.

Also, remember that hands-on learning might be very different from the previous educational experiences of your students. While most of us naturally prefer to learn in a more hands-on way, a traditional education experience of 12+ years has conditioned students to expect to learn in less-active ways. They may not enjoy passive learning through lectures, textbooks, essays, and exams, but at least they understand what to do and how to be successful. Students say they do not enjoy hands-on learning as much as lectures and incorrectly think they do not learn as much because hands-on learning creates feelings of frustration and discomfort as students are mentally challenged by the act of learning (Deslauriers et al., 2019). As teachers, we need to help students recognize struggle, failures, and challenges as an essential part of the learning process—but students, who are always evaluated and ranked by their grades, may be anxious about failure. You can ease their anxiety and help them appreciate failure as a part of their learning process by deemphasizing correctness in hands-on learning. Grading for completeness and effort or allowing time and space for revision are two ways to help students move through the failure stage of learning to the correct answers. Be very clear about how hands-on learning will be graded and how it contributes to the overall course grade from the beginning of the course.

Let the content be the star, not the activity

One of the easiest ways to ruin a hands-on learning activity is for the logistics of the activity or experiment to be more complicated than the concepts students are learning. This problem is best illustrated by an example from a Fun Friday class in Soil Fertility. To teach students how to solve common fertilizer calculations and develop critical thinking skills, we used the Send-A-Problem engagement technique from Elizabeth Barkley’s Student Engagement Techniques (Barkley, 2020). Calculation problems were printed on the outside of envelopes. The first and then the second group of students wrote their solution to the problem on a piece of paper and put it in the envelope. Then, the third group of students critically reviewed the two answers to the question and shared their reasoning. The Send-A-Problem activity did not work well in the Soil Fertility class. There was not enough time in the 50-minute class period to demonstrate how to solve the math problems, explain the logistics of the activity, and complete the activity and concluding debrief, so students left the class feeling frustrated and confused. The next week, we repeated the Send-A-Problem exercise with a new set of questions. However, the students still struggled with learning how to do the calculations and the mechanics of the envelopes and pieces of paper. There was simply not enough time to effectively use the Send-A-Problem activity the way it was used in Soil Fertility. The following year, we revised this lesson by simplifying the activity’s logistics, spending extra time demonstrating how to solve the calculations problems, and providing multiple practice problems. In the second year, students said the hands-on calculation activities were some of the most useful that semester.

This principle also applies to technology. When Google sheets were used for the first time in a hands-on activity, students needed to spend extra time figuring out how to access the document and how to use it in the lesson before starting the exercise. It will take time for students to become comfortable enough with technology to use it to learn the course content you are trying to teach.

Don’t give busywork. Assign work that is challenging.

There is a perfect middle spot between assignments that are too busy, and students see as busywork and activities that are too difficult for students to attempt, let alone be confident in finishing. Hands-on learning activities need to be challenging, engaging, and relevant. You can give students more challenging activities if you are grading their work based on participation and completeness and discussing the answers or solutions in the debrief portion of the class. Activities that are engaging and relevant will not feel like busywork to students. Case studies and discussions on issues that do not have nice, neat, right answers are more challenging than worksheets. The difficulty level is based on the background knowledge and skills students bring to your class and the time, resources, and grading that you give to hands-on learning activities.

Common Objections to Hands-on Learning (And What to Say to Them)

Sadly, hands-on learning challenges the status quo of higher education teaching, even in applied science fields. So, you will likely encounter objections or concerns about the adoption of hands-on learning. Here are some of the common objections to hands-on learning and how you might respond.

“We won’t be able to cover as much content.” No, you won’t. But in today’s digitally connected world, delivering content is not as important as teaching students about context, critical thinking, and application, which hands-on learning does very well. Hands-on learning can do a better job helping students understand how to use and apply information in settings similar to what they might face outside of the classroom.

“It takes too long to create practical hands-on activities. I could prepare and lecture on twice as much content in the same amount of time.” Maybe. Both hands-on learning activities and good lectures take hours to develop the first time but are reused every year with small revisions or modifications. And the amount of time that goes into creating and teaching an excellent lecture class that engages and challenges students and helps them retain information is probably similar to the amount of time it takes to develop a good hands-on learning lesson. The difference in the amount of time it takes to develop hands-on learning activities likely comes from the teacher’s skill and comfort level with hands-on learning, compared to lecture-based teaching. With time and experience, it gets easier to create hands-on learning activities.

“How do I know they’re learning what I want them to be learning in a hands-on activity?” The sarcastic answer to this is, “how do you know they’re learning what you want them to learn from a lecture?” Exams and homework often show that students do not learn what we want them to from lectures, readings, and other class activities. But with hands-on learning, you have direct evidence of what students are learning at the moment. The real concern behind this question likely is, “How do I design hands-on activities to guide students to learning what I want them to know?” and hopefully, resources like this book will help answer those questions.

“Students don’t like it and won’t do it.” Students will also say they don’t like hands-on learning. When students in an introductory physics class were taught using both lecture and hands-on learning techniques, students overwhelmingly said they enjoyed and learned more from lectures than hands-on learning, despite their grades showing the opposite (Deslauriers et al., 2019). In the beginning, you can expect some degree of resistance or lack of engagement from students for hands-on learning. When facing resistance from students be understanding that hands-on learning might be uncomfortable for some students but be clear on your expectations and use an intervention like Deslauries et al. (2019) at the beginning of the semester. After a few weeks of hands-on learning, most students will be more comfortable with hands-on learning.

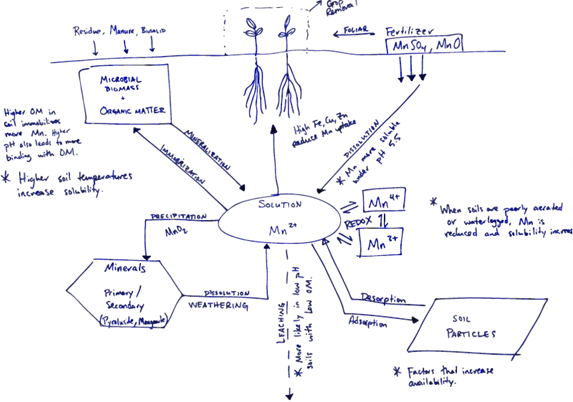

“I don’t have the resources to do hands-on-learning.” Hands-on learning is a frame of mind about teaching, not a physical requirement. With a little bit of creativity, you can do a lot with the most limited resources. Utilize chairs, tables, whiteboards, computer projectors, and any basic office supplies you have access to. You can ask students to bring their own devices and use free or inexpensive digital resources. Ask colleagues or friends if you can borrow equipment or supplies. If you cannot demonstrate an experiment or activity, there are likely online videos you can show instead and then have students practice interpreting the results of the experiment. Inexpensive poster board and colored markers were all students needed for a hands-on activity where they learned about nutrient cycles in Soil Fertility (figure 6.1).

“If students can learn on their own, then what is my purpose?” This is a question no one feels comfortable saying but some of us might relate to. Subject novices can get lost in the weeds, miss the context, have misconceptions or make mistakes, and the guidance of a teacher can prevent, smooth, or reduce these bumps in the learning process. More experienced teachers will have years of stories and experiences in their field to incorporate into realistic hands-on learning activities. And newer teachers will be able to relate to the struggles of mastering the course content and be able to learn along with the students. But, for teachers who view their value to their students only as their accumulation of knowledge on a subject, student-guided hands-on learning threatens their self-worth. Experienced teachers can create practical, challenging, and engaging hands-on activities from their ideas, knowledge, and more expansive teaching practice.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Hands-on learning is an excellent way to engage students in the action of learning within a lecture classroom. When students are active participants in their learning, they will retain more of the information, make higher grades, and develop real-world skills. To use hands-on learning in your teaching, you need to spend time preparing before the semester and throughout the semester. All of your preparation, planning, and hard work will pay off when you can allow your students to learn and practice their course content in the classroom. There will be some challenges that you will face when you teach using hands-on learning. Still, with practice, adjustments, and some compassion toward yourself for failures, you can develop an effective teaching practice using hands-on learning.

Here are some small steps you can take toward using hands-on learning in your classroom:

- As you teach (or learn), think about how the content you are learning could be taught in a more active, hands-on way. Similarly, collect ideas from others on how to make teaching more engaging and dynamic.

- Do a hands-on learning experiment in your teaching. Maybe you have the time and space to redesign a course to focus on hands-on learning, or perhaps you redesign one module or section of a course to include some hands-on learning activities.

- Remember that in hands-on learning, we expect students to make some mistakes or take a less efficient path to the answer, and your hands-on teaching experience will be the same.

Reflection Questions

- Think about a class in which you wish you had been more engaged. What prevented you from being a more active participant in your learning?

- What is the biggest barrier for you to use hands-on learning in your teaching? Are there suggestions, resources, or ideas presented here that could help you overcome that?

- Have you experienced, seen, or heard about other teachers using hands-on learning in their classes? How are they doing it?

Resources and Tools

Active learning while physically distant. Google Doc shared by Louisiana State University https://docs.google.com/document/d/15ZtTu2pmQRU_eC3gMccVhVwDR57PDs4uxlMB7Bs1os8/edit?usp=sharing.

John Spencer’s blog for problem-based learning https://spencerauthor.com/.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science https://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu.

References

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H. (2020). Student Engagement Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H. (2020b). “Problem Solving.” In Student Engagement Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 253–79.

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19251-57.

McKeachie, W., & Svinicki, M. (2013). McKeachie’s teaching tips. Cengage Learning.

Raes Harms, A. M., Presley, D. R., Hettiarachchi, G. M., Attanayake, C., Martin, S., & Thien, S. J. (2014). Harmony Park: A decision case on gardening on a brownfield site. Natural Sciences Education, 43(1), 33-41. https://doi.org/10.4195/nse2013.02.0003

- How to cite this book chapter: Wolters, B. 2022. Fun Fridays: Incorporating Hands-on Learning into Lecture Courses. In: Westfall-Rudd, D., Vengrin, C., and Elliott-Engel, J. (eds.) Teaching in the University: Learning from Graduate Students and Early-Career Faculty. Blacksburg: Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. https://doi.org/10.21061/universityteaching License: CC BY-NC 4.0. ↵