Chapter 8: Siting, Selecting, and Planting

“Right Place, Right Function, Right Plant”

Chapter Contents:

Introduction

A guiding principle often used in landscaping is “Right Plant, Right Place.” You hear it over and over in the plant world, but what does it mean? Basically, it means that the qualities of the plant need to match the characteristics of the site in order to have a successful outcome. Oftentimes, a homeowner spies a lovely tree in the nursery and simply must have it: his or her dilemma is then to find a spot at home where it will prosper. Many a tree has failed because there really wasn’t a good spot for it. In fact, this pattern is backwards: better to find a tree that suits your site in the first place. So, a revised motto: “Right Place, Right Plant.”

More than that, however, we need to consider what function we want the plant to perform in the site. People who want an ornamental tree that also produces fruit may be disappointed on both counts, since pruning for fruit can be very much different from pruning for bloom. If we don’t choose the plant to match the desired function as well as the characteristics of the site, then we put the plant at a disadvantage and may even create a problematical situation. Furthermore, in a world of changing climate and increasing urban forest challenges, failure to think about extremes of heat, wind and precipitation can multiply the effects of a good or bad decision. If we are going to the time, trouble and expense of planting a tree, we want to make sure our investment pays off with dividends. So it really should be “Right Place, Right Function, Right Plant.”

Learning Objectives

- Know how to analyze a planting site.

- Understand the range of functions a tree may perform in a selected site.

- Understand what plant features make a tree suitable for a particular function and site.

- Be aware of potential changes from climate change and socioeconomic factors.

- Know where to find information on trees for difficult sites.

- Understand the sources, types and sizes of planting stock.

- Know how to plant a tree properly.

- Know the basics of immediate aftercare for newly planted trees.

REVIEW: VCE Master Gardener Handbook 2015 (9/18 update)

- Chapter 2, Basic Botany

- Chapter 16, Woody Landscape Plants

Right Place

The very first step in any planting project is to understand the ground. Taken in its broadest sense, this means making notes of all these site factors:

- Heat/cold zone

- Soil texture and structure, depth of topsoil, and soil pH

- If this is an urban or disturbed site, how much real soil is there?

- How much soil amendment can reasonably be done?

- Drainage rate in the soil and drainage patterns across the entire site

- Slope patterns, present and potential with regrading if an option

- Light quantity and direction (noting seasonal progression and deciduous trees)

- Precipitation in the local area (average and extremes)

- Any other moisture sources (streams, vernal pools, periodic flooding)

- Salt from ocean spray or saltwater intrusion, including from road ice treatments

- Local climate change trends and potential for increasing climate disruptions

- Hardscapes which are already there or are planned

- Any access easements which may limit planting of large woody plants

- Utilities, above and below ground

- Present lines, pipes, meters and shutoff

- Future plans for new lines for water, gas and sewer

- Are power lines going to be buried anytime soon?

- Old sewer laterals from house to main

- Septic fields should not have woody plants

Depending on the scope of the planting project, this initial survey may be fairly involved or could be as simple as a home landscape in a Southeast Virginia suburb e.g., cold zone 7a, clay, acid soil – moderate to poor drainage – level ground – full sun – sheltered from winds – standard paving and utilities. There are no apparent neighbor issues but increasing potential for hurricanes and saltwater intrusion.

Here’s an idea for tree stewards to gain experience in this area of effort: practice site surveys, simple or complex, in your own neighborhood. It can be very enlightening to find site-related reasons why certain trees prosper where they do, or don’t.

Microclimates are areas in the landscape where conditions differ from the greater local climate. Microclimates can be a natural phenomenon and they can also be man-made. A south facing hill will be naturally warmer than a north facing hill. So you may be able to grow a plant from a warmer hardiness zone on a south facing hill rather than on a north facing hill. Additionally, you may be able to grow a plant from a warmer hardiness zone next to a brick wall. The heat absorbed and then released by a brick wall can make that site warmer than the surrounding area.

If you have an exposed site, a site with no shelter from the wind, it can be a bad location for trees that may be marginally hardy. If you have a protected site, a site with shelter from the wind, marginally hardy trees may survive for many years but may succumb if there is an extremely cold winter. The southern magnolias below are espaliered against a south-facing brick wall, enabling them to prosper north of Richmond.

The tree steward needs to consider prevailing winds and possible extreme situations. It is also worth remembering that shallow pockets or the bottom of valleys will tend to retain cold air in winter: a natural microclimate of cold.

Space and Geometry. One matter which is often overlooked in site planning is the available space for the true spread of the canopy and of the roots. Above ground, if the space is narrow but tall, then a broad spreading canopy will not work. This is fairly well understood by negative example. What is less well appreciated is the importance of the space below ground, considering the soil type, depth of the soil horizons, drainage and physical infrastructure (now or planned). A situation with shallow drainage but lots of sidewalks is potentially problematic: a shallow rooted tree will tend to disrupt the pavement. So the tree steward might want to look more at a deeper rooted tree with known tolerance for wet soils, such as the swamp chestnut oak [1]. Deep rooted trees including white oaks should also be better able to adapt to increasing periods of drought. [2] Note that even a deep rooted tree will have surface roots in compacted soils, since the space between sod and compaction can be a friendly place for roots to spread. Also, a tree with a wide spread of shallow roots may have its own dynamic stability, as with the beech below, assuming it has been given enough space.

One final thought in site analysis is the context, meaning the history and probable future of the site. Left to itself, what would be the noninvasive natural growth? What are the societal and/or economic factors which may affect the site? Are there known plans for building or road construction in the area? Looking longer term, how is the surrounding area likely to be affected by urban sprawl, sea level rise, and overall climate change? Are there site vulnerabilities which are now considered acceptable but which could become problems with increasing climate disruption events?

Right Function

Once you have surveyed the site, (or even before), you must think through why the planting project is wanted. A basic set of questions may shed light.

Who is the authority? If a homeowner, this may be relatively straightforward. Otherwise, it is important to know who wants the planting, who makes the decisions, who pays the bills and who will maintain the plantings. Be sure you know if there are any environmental restrictions or requirements.

Human Health and Aesthetics: For the flowers, foliage, bark, even fruit. Consider winter interest. And who doesn’t love the snow fountain cherry in spring?

Beyond the purely ornamental aspects, all those pretty trees have real health and social benefits in urban settings, as shown by an increasing number of studies. [3]

Production: Sap has historically been one of the most useful tree products: resin from the pines or gum from the sweetgum (look it up!). Tree nectar from the sourwoods is an important feed for honeybees, as are the native basswoods. Hickory nuts are an important food source for wildlife. The osier dogwoods provide the fancy red whips in spring for decorators (or just for people to enjoy). There are secondary production opportunities such as growing certain oaks to serve as hosts for truffles. And not least at all: fruit!

Another major consideration is the time horizon. Even if you are thinking of just this year or next for the desired effect, trees have their own, much longer timelines. So, if you decide to plant a larger tree now in order to have a full canopy in a matter of just a few years, you (or whoever comes after you) may be living with that tree for many years. In fact, it is much more important to consider the eventual size of a well chosen and properly planted tree rather than its size in a narrow, human perspective of 5 to 10 years. Note that commercial plant labels may be giving you just that 10 year number: do some research on the species before investing.

Finally, there are other functional considerations, of which this list is only a sample:

- City/county ordinances or HOA rules

- Budget (including maintenance)

- Grant requirements or civic themes

Right Plant

Once the site has been analyzed and the reasons for planting have been laid out, it is now time to think about what kind of tree(s) and other plants to choose. It is probably useful to think about what requirements of either site or function will limit the choice of plants: Hardiness, growth habit, growth rate, max size (above and below ground), moisture needs, and particular features (good or bad) are all important in making the right selection. One should also consider tradeoffs of quick growth vs longevity, maintenance needs, and the potential to handle climate changes and disruptive events. If you are framing the discussion in economic terms, remember that return on investment can be considered in other terms than dollars.

Hardiness

This is the first limiting plant feature. Another way to speak of this trait is that some plants can handle a wide variety of physical and climatic conditions, while others are much pickier. Trees are so much larger and longer lived than other plants that people’s short term adaptations (such as irrigation) don’t make all that much difference in the tree’s long term survival. Range is the word used to describe the locations and environments in which a tree species will normally prosper. One of the most important factors in determining a tree species’ range is how well it handles low temperatures. USDA publishes a Cold Hardiness Zone Map with a colored key. Virginia spans four of these zones: the coldest is zone 5a in the mountains, and the extreme Southeast, plus the Eastern Shore, just edging into zone 8. This represents a variable of 30 degrees Fahrenheit, from -20 degrees to 10 degrees, in the historic extreme minimum temperatures each year: a considerable difference between a Frasier fir and a southern magnolia! A Heat Tolerance Map, if available, can be important in urban heat islands or locations with high temperature spikes in the summer. Most plants tags give only the Cold Zone number, but horticultural sources may give both, usually Cold Zone first. Since the numbering systems are similar though not identical, it is important to know which one you are looking at.

Temperate zone trees naturally grow in forests, and that is where we should look first for information about their suitability to different environments such as cities. Tree books often describe what sort of terrain trees prefer, and foresters have insight into this as well. Trees that grow on mountain tops are accustomed to dry, less fertile sites (some oak and pine), while bottomland trees are better at handling poorly drained soils (other oaks, sycamore, elm). Mid-slope trees come somewhere in-between (tulip poplar, beech). And some trees are quite versatile (red maple, persimmon, eastern redcedar, black gum).[4]

In a world of changing climate, we are seeing the distribution patterns of some trees changing in the forests. For example, in the forest biomes covering Virginia, it looks like loblolly pine, sweetgum and a number of oaks are pretty good bets. [5] Check Chapter Seven for suggestions of online resources for projected species distribution. Generally, in human-built environments, we should be looking for trees which are resilient in the face of climate extremes and structurally able to handle disruptive events. Also, the larger and longer trees grow, the better for carbon reduction [6]and stormwater management. [7]

Growth Habit

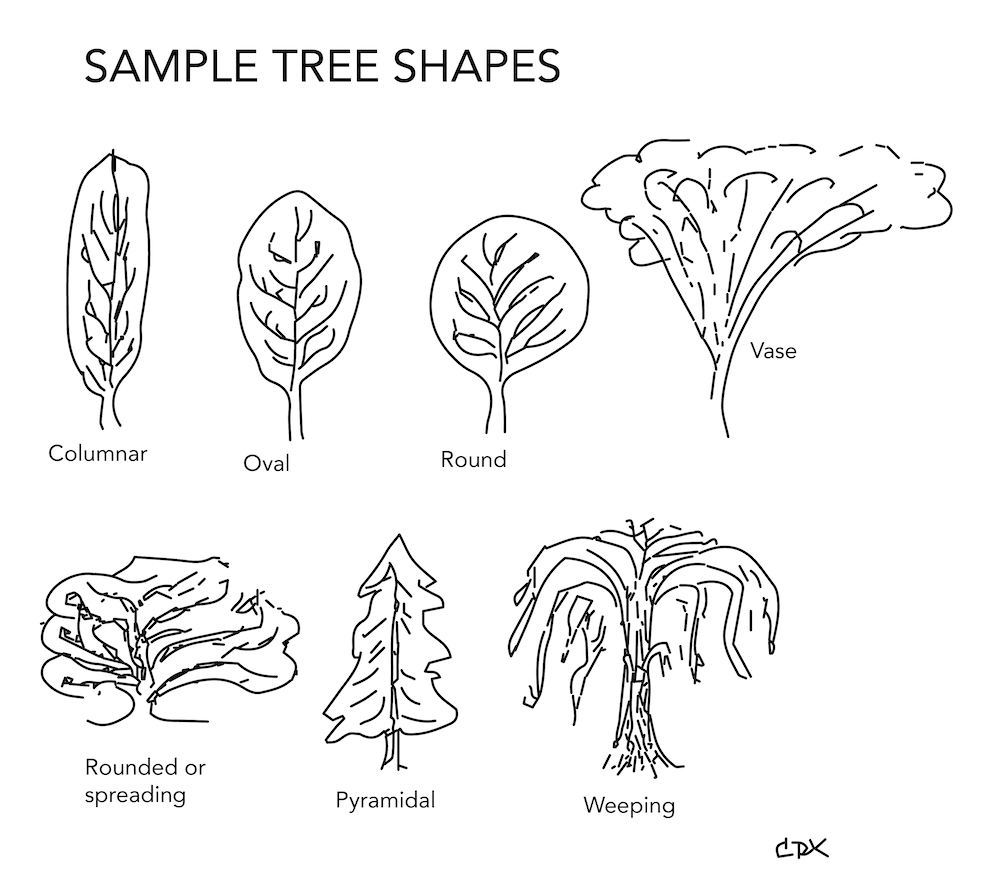

Each tree has a natural habit or form. Often these are common to an entire species or even genus, but some trees have been developed to have cultivars in all sorts of habits. For example, the bald cypress normally has a conical outline, but you can get one that is weeping instead. Some common tree forms are columnar, oval, round, pyramidal, spreading, weeping and vase. Some tree forms are better suited for certain locations than others. A tree with a natural vase shape is a better selection close to a driveway than a weeping tree where the branches will be constantly hanging down over the parked cars and need pruning. When selecting a tree, be sure to match the form to the function.

Growth Rate

Different trees grow at different rates. Does the growth rate suit the function for that tree? A fast growing evergreen is often selected for screening, with consideration for the strength and health of the roots which may be subjected to winds. Or you may wish to select a slow growing tree such as a specialty Japanese maple near a house where you will most likely not need to do very much pruning. In a larger setting such as a municipal park, it may even be wise to select trees with naturally good branch structure and a less rapid growth rate, such as the blackgum, which will lessen the workload on the maintenance crews over time.

Many times, fast growing trees are often weak trees. A silver maple is a fast growing shade tree, but it is very weak wooded and tends to have multiple trunks from a single point. You would not want to plant a silver maple near a structure, fence or vehicles. As those trunks or branches fall, they can do damage to whatever is below.

Maximum Size

Many times trees are planted without thinking about their potential size. This can lead to future problems where people are attempting to control tree size through pruning, which may not be realistic depending on the specific tree. We have all seen instances of a cute little tree planted next to the front porch, which then grows to take over the doorway and path. This comes from not believing the label: it may be 3 feet tall and wide now, but 20 feet by 20 feet is something else again.

Commercial plant labels should be read with some caution, as well: the given max size may be the final size for that species, or an estimate in ten years’ time. If the latter, the label will not usually tell you that detail. So, be sure to check a couple of other sources for max size. Finally, even if the label gives a reasonable maximum size for that tree, if the tree is really happy it will ignore the label and set its own record.

A word is in order here about overhead wires and their supporting poles. There are a few trees (or rather, varieties or cultivars of certain species) which have been tried out to see if they will remain small enough to avoid the attention of utility tree-trimmers. The VCE Pub on this subject is listed in Table 8-1, later in this chapter. However, individual trees do not always behave as expected and the power line situation gives very little room for miscalculation.

One trend in urban landscapes is homeowners’ reluctance to keep or plant trees for fear they will fall. It is important to respect this attitude, but education can point out that healthy, well maintained trees of good structure are much less likely to fail while still providing ecosystem services. For planting new trees, such sites may benefit from small to medium size trees with reasonable longevity and pest resistance, such as yellowwood and redbud. [8]

You should look for information about how the root system grows when researching potential trees. You may want to go look at mature specimens to see how they do in your locality and soil. Generally, a shallow rooted tree is not suitable for planting near sidewalks or driveways. It is also hard to establish planting beds under shallow rooted trees. Some trees have aggressive root systems that seek moisture. For example, willow trees seek moisture so they are not a good selection to plant near a septic field.

Moisture Needs

Many of the most successful urban trees are those which grow naturally in challenging environments and tolerate changes in moisture and temperatures. Examples include red maples, sycamores (and their cousins the London planetrees), bald cypress and the dinosaur-survivor ginkgo.

On the other hand, if the planting site is prone to standing water after a heavy rain, then you should avoid trees which don’t tolerate wet feet (e.g., redbud) but go instead to those which can handle some extra water from time to time. Some of the best of these will be listed in the various publications about rain gardens. The sweet bay magnolia is an excellent example for eastern Virginia.

Particular Features (Bad and Good)

Problems to avoid: When researching potential trees, also look at disease and pest concerns. You may find that the potential disease and/or pest concerns would warrant that you not choose to plant a certain tree. For example, ash trees are wonderful shade trees. However, with the introduced pest, Emerald Ash Borer, moving into the region, you would not want to select that tree for any future plantings. The Leyland cypress is another example of a popular and beautiful tree which is prone to a number of pests and diseases, including in the roots: most of us have seen a lovely long screen of these with gap teeth where individual trees have succumbed.

Research is always important. You may find that the tree you want to plant has disease resistant varieties. For example, there are some selections of crape myrtle trees that are powdery mildew resistant. Or trees may have been developed to avoid undesirable features, as with the thornless honey locust.

Flowers and fruits can be potential issues. A sweetgum, while a great shade tree, would not be an appropriate choice for planting in a lawn. It drops its stiff seed pods, called gum balls, which make the yard not very enjoyable to walk and play in. A saucer magnolia is a beautiful medium sized flowering tree. However, if you plant it overhanging a sidewalk, it can become a slippery mess for a week or so in the spring when all the large, soft petals drop on the ground beneath. Another interesting fruit hazard is the ginkgo. The fruit of the female tree, when ripe and fallen to the ground, has a strong odor. The seeds are an Oriental delicacy, but understandably most landscape plantings are male trees (however see pollen, next below).

Another flower feature worth discussing: pollen. Oaks, pines and maples are wind-pollinated, meaning that the trees send out clouds of minute pollen grains to try to contact the equally small female flowers. Note this does not mean that such trees are male/female necessarily. For many allergy sufferers, mid-spring can be quite miserable. Wind-pollinated trees can be recognized because their flowers come out before their leaves, generally speaking. One possible answer is to diversify with other trees whose flowers arrive with or after their leaves. Many of these rely on (and thus benefit) insect pollinators, such as linden/basswood, blackgum and tulip poplar.

One of the most enjoyable parts of process of tree planting is choosing among the many attractive plant features available. As we have already said, this step may be where many people start. But if we really want the tree we plant (whatever it turns out to be) to prosper, we don’t start choosing plant features until we understand the site and the intended function. If we are growing a tree for harvesting fruit, sap, nuts or other use, then specialty research is definitely appropriate, including soil needs. If the purpose is a screen or windbreak, the key features will be root strength, branch structure, foliage and growth rate. Which brings us to the ornamental qualities of leaves, flowers and bark.

Leaves are, of course, the food producing part of the tree. But they do many other tasks for us: shade, water transpiration (cooling the air), intercepting aerosol and particulate pollution, food for insects, habitat for wildlife. Looking at the ornamental and practical decisions, the first decision is evergreen or deciduous. Note that all the leaves eventually fall off of trees: evergreens keep the old ones until after the new ones arrive (sometimes over several years). The size of the leaf and the timing of deciduous leaf fall can be important if you will be spending hours raking, but may be worth the glorious fall color.

Conifers are usually among the easiest trees to care for, with evergreen foliage and cones instead of fruit. The eastern redcedar is an example of one which is also very good habitat for wildlife.

Leaf thickness is also a consideration. Thick leaves, such as the southern magnolia, usually provide shadier conditions underneath it. This makes it harder to plant or grow anything underneath it. These leaves are also harder to remove or mulch. Thinner leaves usually provide less dense shade and tend to be easier to remove or mulch.

All broadleaf trees produce flowers, but not all flowers are notable. However, we may be selecting trees for those notable flowers. The time of the year the tree flowers may also be of consideration. Depending on the species, trees’ flowering seasons may be anytime from late winter to late summer.

It may also be considered an asset if the tree provides nectar for bees and other insects. Examples are black locust, tulip poplar, and the tilias (native basswood and well-adapted littleleaf linden).

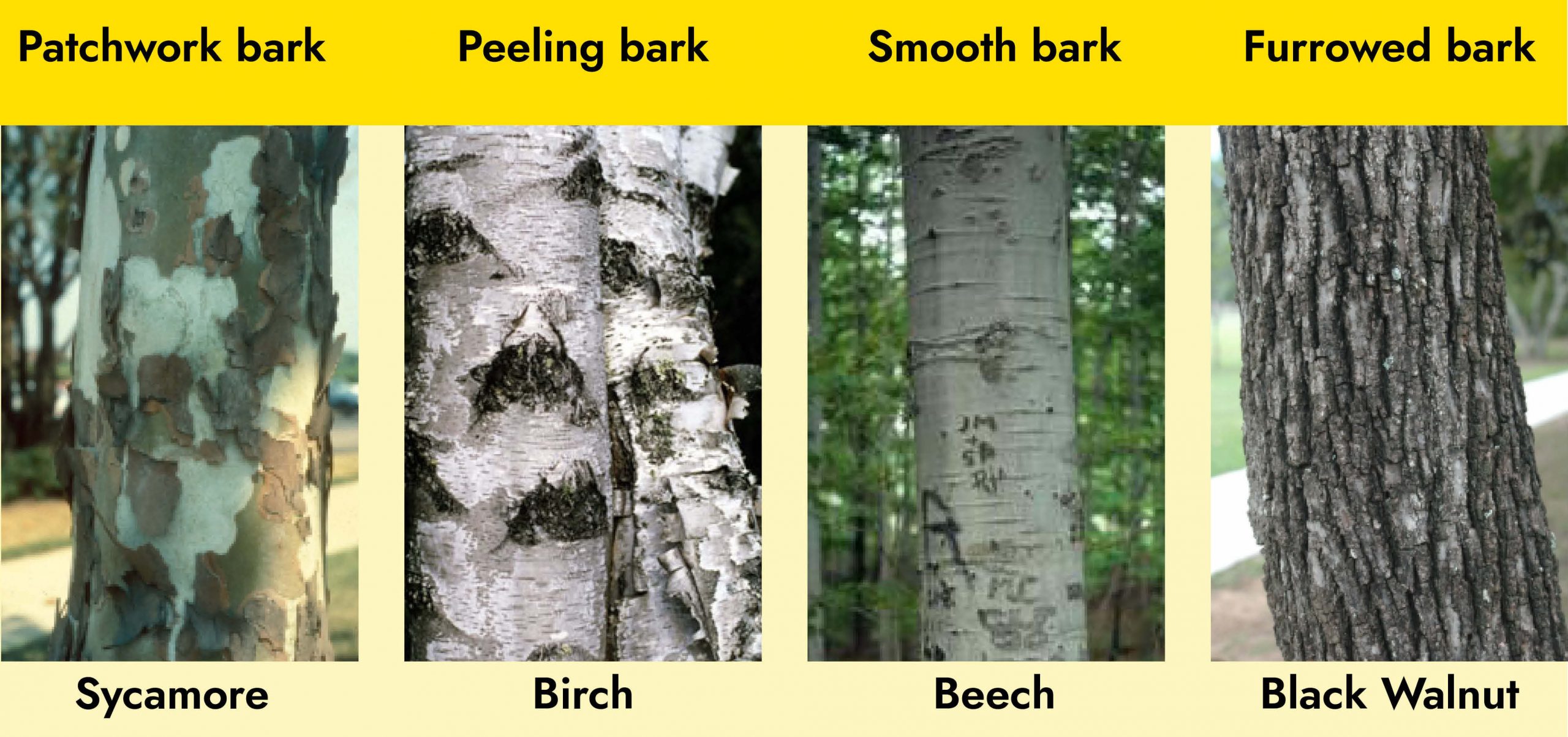

Bark is another feature which may influence landscape choice. Some tree species are noted for unusual bark which can add interest to a garden, especially in winter.

Natives versus Non-Natives

Native plant gardening is a current trend in gardening. Planting native trees certainly falls in with that trend. A native plant is considered to be one that grew in a certain locality prior to European settlement. The local fauna and other flora evolved with those native trees around. A native tree’s natural habitat can give us clues as to where descendant tree may thrive. For example, red maple trees are found in wild bottom lands and moist soils, hence its other common name, swamp maple. Therefore, if you have a damp location, this tree may be a good choice.

Non-native trees, then, are ones that have been introduced to a region after European settlement. Non-natives can open up a whole new range of plant features that may not be available with a native tree choice. They may also be important as we look ahead at the challenges posed by difficult urban environments and general climate change dynamics. Increasing extremes of heat, precipitation and wind may make a nonnative from a harsher climate a reasonable choice in the landscape.

When considering a non-native tree, you also have to address its potential for invasiveness. Nonnative invasive plants have negative effects on biodiversity (i.e., the rich genetic resource of flora, fauna, and microbes) at the ecosystem level and the community and population levels. Examples of how invasive plants threaten the health of natural areas are:

- Replacement of diverse systems with single stands of nonnative plant species.

- Changes in soil chemistry, land form processes, fire regime, and hydrology.

- Competition with endangered plant species.

- Failure to support native insects and animals while displacing plants that do.

To consider just one example, the mimosa is a non-native tree that does very well in poor urban soils, has a beautiful summer flower, and is easy to clean up in the fall. The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation lists this tree as having a medium invasiveness ranking. Indeed, you can see this species in disturbed areas where it can easily displace native vegetation that would otherwise grow. As a result, you would not want to select and plant this tree.

Here is a native gardener’s dilemma. The modern plant breeding industry is constantly striving to develop new plants with desirable features such as smaller size, better shape, or disease resistance. Do these cultivars and hybrids of native plants support ecological functions as well as their wild relatives? Should we label such cultivars and hybrids, sometimes called “nativars,” as native plants? There are no decisive answers to these complex questions, although Doug Tallamy’s research at the University of Delaware[9] suggests that in some cases nativars are more attractive to pollinators or leaf-feeding insects than their wild parents, and in others they are less so. It is also possible that designed hybrids may have a role in the changing environment of the future.

Trees for Difficult Locations

Planting the right tree in the right place can be difficult sometimes. There may be environmental conditions or man-made conditions that make that site challenging to grow trees. Virginia Cooperative Extension has many publications available to help with the selection of trees for difficult sites.

VCE publications on trees (look up by the numbers) on VTechworks:

- Selecting Landscape Plants: Rare and Unusual Trees: Publication 426-604

- Trees for Problem Landscape Sites – Air Pollution: Publication 430-022

- Trees for Problem Landscape Sites – Trees for Hot Sites: Publication 430-024

- Trees for Problem Landscape Sites – Screening: Publication 430-025

- Trees for Problem Landscapes – Wet and Dry Sites: Publication 430-026

- Trees and Shrubs for Acid Soils: Publication 430-027

- Trees for Parking Lots and Paved Areas: Publication 430-028

- Trees and Shrubs for Overhead Utility Easements: Publication 430-029

- Trees and Shrubs that Tolerate Saline Soils and Salt Spray Drift: Publication 430-031

- Trees for Containers and Planters: Publication 430-460

Obtaining and Evaluating Planting Stock

Types and Sources of Planting Stock

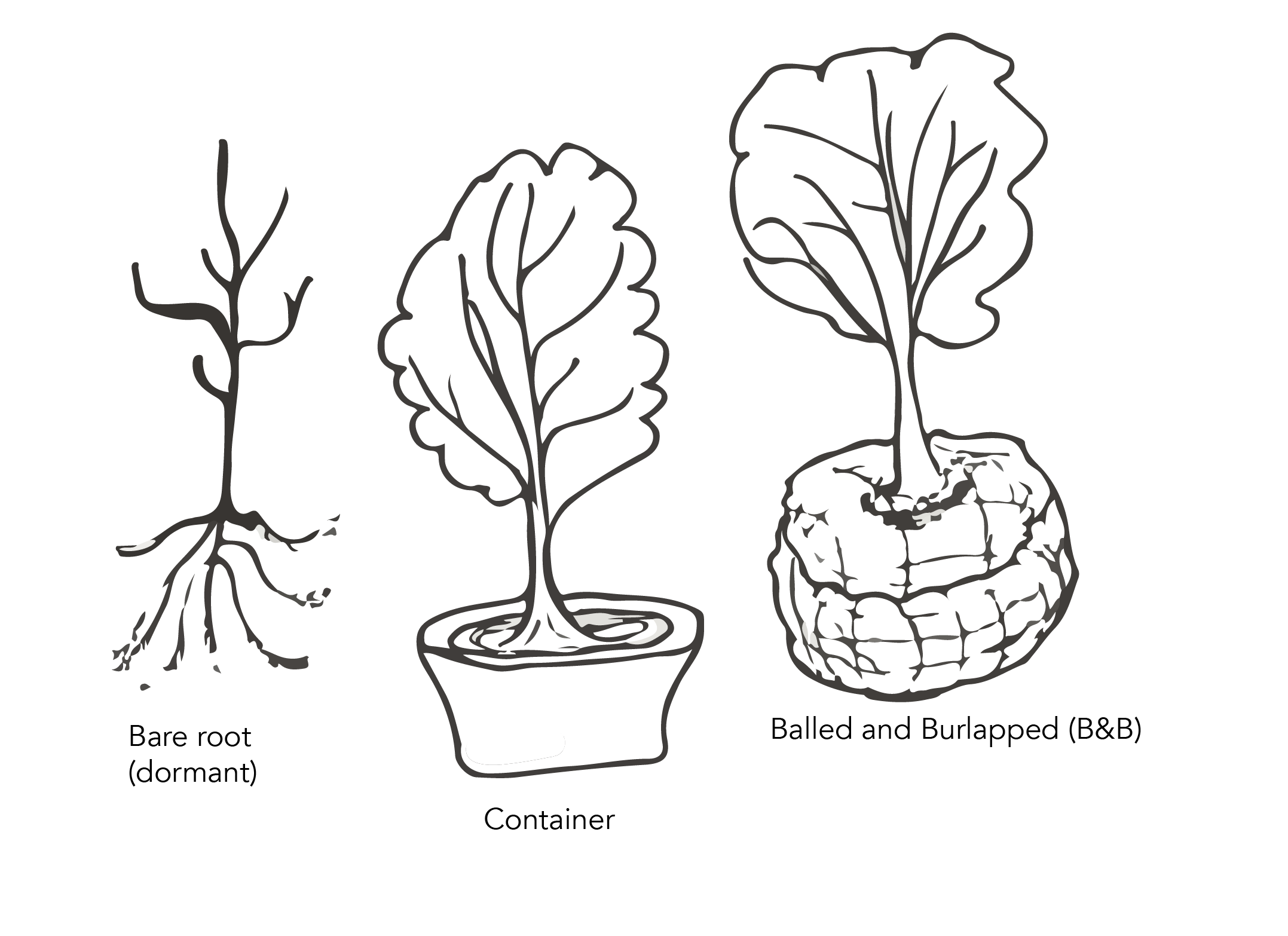

There are many different sources, types and sizes of planting stock. Every one of these has its pluses and minuses. So, while one type of planting stock may be appropriate for one situation, it may not be appropriate for another. Being aware of these pluses and minuses can help the consumer in making an informed decision. Trees may be purchased bare root, in a container, or balled and burlapped (B&B), where the root ball is wrapped in burlap type material.

Bare root trees are often the least expensive type. However, they are typically only available during the dormant season. They will usually only be available by mail order, and the tree size is usually only available from seedling size to 8 feet tall.

Container trees are typically available year round. They are easily available in most localities. Their cost is generally more than bare root trees, but less than B&B. The tree size for containers can be from seedling size to typically a 2 inch caliper.

B&B trees are typically available year round. However, sometimes their availability is limited during the late summer/early fall as retailers sell out of stock, since these trees are usually only dug from the field and shipped when they are dormant. These trees are generally going to be more expensive because of the shipping costs for the larger, heavier root ball. Tree size is generally from the 6 to 8 feet range and larger.

When choosing planting stock, bear in mind that the smaller the tree when planted, the less time it takes for the tree to become established in its site. If the tree has been grown properly, whether in container or B&B, it should have some absorbing roots in the root ball and also not have circling or girdling roots (see below). Still, if the crown of the tree is significantly larger than the root ball, it will still take time for the roots to catch up. Thus, the tree steward should not be afraid to plant a very small tree, as long as it can be protected from lawn mowers and deer by tree guards and fencing.

There are many sources of planting stock, but they can typically be put into two categories, mail order or nursery and garden center. Mail order sources can be great for purchasing rare or unique trees. They typically have smaller material available to ship because of shipping costs. Many times you can get the material as bare root, which must be planted right away or else potted up temporarily until time for planting. Nursery and garden center sources typically have a limited supply, generally just the locally popular trees. The material will usually be either containerized or B&B. You can generally get larger plant material from a local nursery and garden center than from mail order sources. If you are fortunate enough to have a small nursery/garden center in your community which can take orders, by all means give it a try. You may also be able, as tree stewards, to propagate your own trees from local specimens or to find a group already doing so.

Evaluating Planting Stock

Once you have decided on a type, source and size of stock, you will need to check the actual tree to make sure it has a good chance of survival.

The most important inspection is of the root system. The main characteristics of the root system are covered thoroughly in Chapter Four. Purchasing a bare root tree allows you to be able to examine the tree’s entire root system and take any corrective actions before you plant it. If purchasing a containerized or B&B tree, you should be able to probe gently (check with the store first) to see how deeply the main roots are buried and how compacted the soil is. If you have already purchased the tree, you can wash the soil off the roots to expose the root system for inspection. If you do this, be sure to keep the roots wet and plant the tree promptly after taking any corrective action.

There are some scenarios to avoid when purchasing trees. Avoid plants without sufficiently developed fibrous roots that hold the root ball together. This is usually easily seen in container trees. In B&B trees, avoid root balls where the soil in the ball feels loose and broken up. Avoid trees with circling or girdling roots. Again, this is easier to see with container material, and often difficult to see underneath the burlap and cording of B&B trees. Lastly, avoid trees that have excess soil on top of the root ball. This is typically found in B&B material as extra soil tends to be placed on top of the root ball during the digging process.

The second main inspection area is the crown and trunk. Generally, a tree with good crown configuration will have branches in the top two-thirds of the tree. If the tree has had too many lower branches removed, it will have its crown concentrated towards the top of the trunk. This makes the tree more susceptible to winds needing staking. Major branches should not touch and they should be less than two-thirds the diameter of the trunk. The crotch shape should be a U-shaped crotch rather than a V-shaped crotch. Additionally, the leader of the tree should not have been pruned. If it has been pruned, make sure that a new leader was properly selected and trained. Are the branches damaged or broken? Often you can prune out the damaged material, but in pruning it out, you should consider how that will affect the overall shape of the crown.

The trunk should generally be straight and without defects other than proper pruning wounds. Inspect for bark damage to the trunk from shipping. Avoid trees with injuries to the trunk as these can lead to disease and insects. Additionally, look for evidence of sunburn on the trunk. Sunburned bark initially appears discolored; often a reddish-brown, it then becomes dry and sunken. It is often the result of the young, thin bark of the tree suddenly being exposed to direct sun. This can happen often in the nursery or garden center when trees are removed that are providing shade to the trunk of the young tree.

The third step in inspecting planting stock is to evaluate the overall health of the tree. If you are able to look at the other trees around it, ask yourself if the tree you are purchasing appears to be in generally good health and vigor as compared to the others. Generally pests and diseases should not be a problem when purchasing a tree, because of the inspections that should be done at the nursery and retailer. However, depending on how long the material has been at the retailer, you may end up seeing disease or insect problems. Look carefully at the foliage. If it is speckled or spotted, it may have a disease or be infested with sucking insects such as spider mites or aphids. When inspecting the trunk and branches look for bumps or raised ridges that flake off with your fingernail. If you expose green or white tree tissue, then this was just a normal growth of the tree. If you see intact bark under the removed bump or ridge, it was most likely a scale insect.

One might ask what the nursery industry does to keep (or improve) the quality of their offerings. First, there are the ANSI standards and the best practices based on them (see Chapter One). Then there are state-level criteria, among which Florida’s is an excellent example: Florida Grades and Standards for Nursery Plants 2015, which measures such things as the straightness of the trunk and the shape of the canopy. [10]

Shovels in the Ground

There is an old gardening saying that goes like this: “Plant a $10 tree in a $100 hole, not a $100 tree in a $10 hole.” In other words, you can make a real difference in the general health and future growth of a tree by properly preparing the hole that you plant it in.

The basic guidelines for tree and shrub planting can be found in VCE publication 430-295 “Tree and Shrub Planting Guide.”

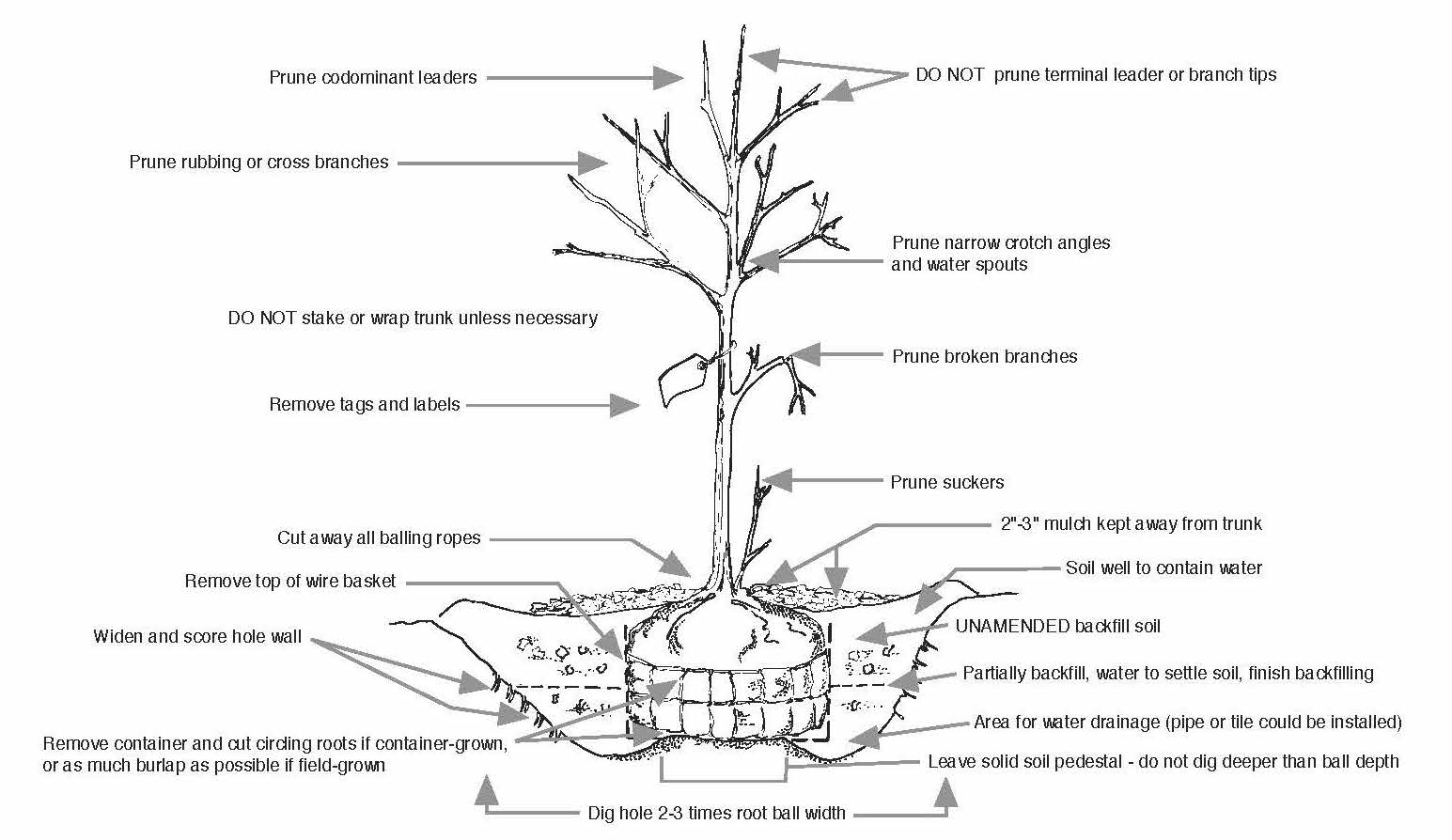

Dig shallow planting holes, two to three times as wide as the root ball. Wide, shallow holes encourage horizontal root growth that trees and shrubs naturally produce. In well-drained soil, dig holes as deep as the root ball. In poorly-drained heavy clay soil, you may want to plant a bit higher, with holes one to two inches shallower than the root ball. However, it is really better to select a tree appropriate for a soggy site and plant with the root flare at ground level. If you are planting bare root, the hole should not be any deeper than the depth of the actual roots. Do not dig holes deeper than root balls or put loose soil beneath roots because loose soil will compact over time, leaving trees and shrubs planted too deep.

Carefully place the tree in the hole if it is bare root or B&B. If it is containerized, carefully remove from the container, clean off any accumulated mass of small roots, remove girdling roots, and place the tree in the hole. If B&B, remove cording, burlap, and wire basket if present. Now is the time to remove circling or girdling roots at the point of any hardened major angle. Also, make sure that the root flare has been exposed, and the tree is positioned with the root flare at the soil line.

Backfill the hole with existing, unamended soil. Do not incorporate organic matter such as peat moss into the backfill for individual planting holes. Not only will this inhibit the roots from venturing past the planting hole, but differences in soil pore sizes will be created causing problems with water movement between the root ball, planting hole, and surrounding soil. Backfill the hole around the tree with half the soil and water thoroughly to settle out air pockets. Finish backfilling, and then water again.

Mulch, but do not over mulch, newly planted trees and shrubs. Two to three inches of mulch is best. Use less if the mulch is a fine material, and more if it is coarse. Use either organic mulches (shredded or chunk pine bark, pine straw, composts) or inorganic mulches (volcanic and river rocks). Keep mulch from touching tree trunks and shrub stems. This prevents disease and rodent problems if using organic mulches, and bark abrasion if using inorganic mulches. One traditional approach is the 3-3-3 mulching rule: Have the mulch ring be 3 feet in diameter; 3 inches deep; and 3 inches away from the trunk.

Prune out any broken branches or give a good clean cut to branches that may have been broken off. Try not to prune the end of the leader or any branch tips, since these are the main source of essential growth hormones. After the first year in the ground, and once the tree has begun to shows signs of growth, you may start a gradual regimen of preventive pruning, removing any branches that have narrow crotch angles and any branches that may be crossed and rubbing other branches (to avoid future injury).

Most trees should not have their trunks wrapped unless they need temporary protection from deer or rabbits. Wrapping often increases insect, disease, and water damage to trunks. Make sure to remove any wires, labels or flagging tape to avoid girdling the trunk or branches in the future.

Staking with guy lines should be done only to provide initial, temporary support for a tree in an unstable situation. Examples are trees with large crowns, those situated on windy sites, and those in danger of being pushed over by crowds. Be sure that the portion around the trunk is loose enough to allow the trunk to move a little bit. Guy lines should be removed within a year at maximum. Not only does a forgotten guy line risk the collar girdling the tree as it grows beyond the size of the guy line collar, but unnaturally rigid trunk and roots will not develop the natural strength to handle normal wind loads. Wooden stakes, cut off for safety, may be left in the ground to rot. In fact, stakes without guy wires may be sufficient if the reason for the structure is visibility to pedestrians or mowers.

Aftercare

Watering during dry periods of the first growing season is crucial, especially with container grown plants. Container and B&B tree roots dry out faster than the soil around them, so it is particularly important to take care of their soil moisture. In the nursery, the roots of container and B&B trees become concentrated in a small root ball which is watered daily. After planting, the roots of these trees will eventually spread into surrounding soil. Until that happens, however, the trees continue to draw water mostly from their root balls. Consequently, if the soil near the trunk is dry, the trees need water, at least until the first winter. Water newly planted trees deeply once a week during periods of no rain. It is best to water slowly, as with a garden hose, to soak the soil thoroughly. Always allow the water to reach the top of the berm built around the plant. This will provide deep water penetration and encourage widespread root development. If there has been any rain in the previous week, check the soil moisture to avoid overwatering, as this can kill the plant.

Once the tree has gone dormant in its first year, it will begin to establish its equilibrium. In the next year it should be on the normal schedule for its type of tree. If the site is appropriate for the tree and function, then it should not need special care after this, except in unusual weather. An exception to this guidance is for those brave tree stewards who have planted a seedling: it will need regular watering (weekly or more, depending on summer heat) until it has got to about three feet tall, perhaps two years. The good news is that it will never have the absorbent differential issues discussed above with larger stock.

Whatever your source and choice, watch the new tree and see what it tells you. If it was well matched to the site and function, it will let you know.

Review Questions

- What are some characteristics that make a tree appropriate for a particular planting site?

- Where can information on selecting trees for difficult sites be found?

- What are the sources for stock for trees?

- What are the types and the sizes of tree planting stock?

- How is a tree planted properly?

- Kirkman, L.K., Brown, C.L., Leopold, D.J. (2007). Native Trees of the Southeast. Timber Press. ↵

- Vose, J.M., Elliott, K.J. (2016). Oak, Fire and Global Change in the Eastern USA. Fire Ecology, 12 (2), 160-179. ↵

- Wolf, K.L., Lam, S.T., McKeen, J.K., Richardson, G.R.A., Van den Bosch, M., Bardekjian, A.C. (n.d.). Urban Trees and Human Health: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 202(17), 4371, doi:10.3390/ijerph17124371 ↵

- McGlone, J. PhD. (2020, June). [PowerPoint] Landscape Woody Plant Adaptations: A View from the Forest, VCE Master Gardener College. ↵

- Rogers, B.M., Jantz, P., Goetz, S.J. (2017). Vulnerability of Eastern US Tree Species to Climate Change. Global Change Biology, 23, 3302-3320, doi:10.1111/gcb.13585 ↵

- Nowak, D.J., Stevens, J.C., Sisinni, S.M., Luley, C.J. (2002). Effects of Urban Tree Management and Species Selection on Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Journal of Arboriculture, 28 (3), 113-122 ↵

- Berland, A., Shiflett, S.A., Shuster, W.D., Garmestani, A.S., Goddard, H.C., Herrmann, D.L., Hopton, M.E. (2017). The Role of Trees in Stormwater Management. Landscape and Urban Planning, 162, 167-177 ↵

- Kirkman, L.K., Brown, C.L., Leopold, D.J. (2007). Native Trees of the Southeast. Timber Press. ↵

- Tallamy, D. (2007). Bringing Nature Home. Timber Press. ↵

- Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. (2015). Grades and Standards for Nursery Stock (5th ed.). ↵