Chapter 5: Tree Taxonomy, Identification, and Measurement

“The wonder is that we can see these trees and not wonder more.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

Chapter Contents:

Introduction

There are many ways of identifying trees. This chapter describes dichotomous keys, the taxonomy of trees, and tree families. Dichotomous keys are a scientific method where the user is led through a series of choices that ends with the selection of a specific tree. Trees may be understood in terms of where they are located in the hierarchical categorization of living things (taxonomy). Tree families share certain common characteristics: understanding those characteristics enables the user to more readily identify specific trees. As later discussed in Chapters Eight and Ten, tree identification is particularly important for Tree Stewards because it is an essential element of selecting the right tree for the right place and a critical aspect of determining tree disorders, associated causal agents, and appropriate courses of action.

The chapter concludes with descriptions of the National and Virginia Big Tree Programs and provides guidelines for measuring trees.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the use of dichotomous keys to identify trees.

- Be familiar with the taxonomical approach for classifying plants and the points at which major changes occurred in plant characteristics.

- Have an awareness of the concept and significance of tree families.

- Understand the use of observable characteristics as quick identification aids for trees.

- Be familiar with the Big Tree program at the national and state levels.

- Identify the three dimensions of trees and know how to measure them.

REVIEW: VCE Master Gardener Handbook 2015 (9/18 update)

- Chapter 2: Basic Botany, Taxonomy: Biological Classification, Anatomy: Plant Parts and Functions

- Chapter 16: Woody Landscape Plants, Plant Nomenclature, Woody Plant Categories

Dichotomous Keys

A dichotomous key is a scientific tool for identifying trees. Dichotomous keys also exist for identifying other items in the natural world such as various types of living things or even rocks. Any dichotomous key leads the user through a series of steps where at each step the user must select among two choices. A common first step for trees is:

- Leaves are needle or scale-like, go to x

- Leaves are broad and flat, go to y

The selection at each step leads to a designated next step ultimately resulting in the identification of the tree.

There is no single dichotomous key for trees. Keys may be simple or complicated. Some keys, such as the one in Tree Finder: A Manual for the Identification of Trees by Their Leaves, are based solely on characteristics of the leaves.[1] Others may include traits such as bark, twigs, leaf scars, buds, and seed production (size and shape of cones, acorns, etc.). The power of any key is only as good as the set of plants that it includes. However, in general, the more trees included in the key, the more complicated the key.

The ability to correctly identify a tree based on a dichotomous key is limited by the accuracy of the user’s observations, the ability of the user to understand the choices posed by the key, the season of the year (a key based on leaves is not very useful for identification in winter), and the scope of the key. The tree of interest may not be included. For example, the dichotomous key in Common Native Trees of Virginia will not help identify a zelkova.[2] While zelkovas are increasingly planted in Virginia, they are native to East Asia and thus not included in a book on native Virginia trees.

Taxonomy of Trees

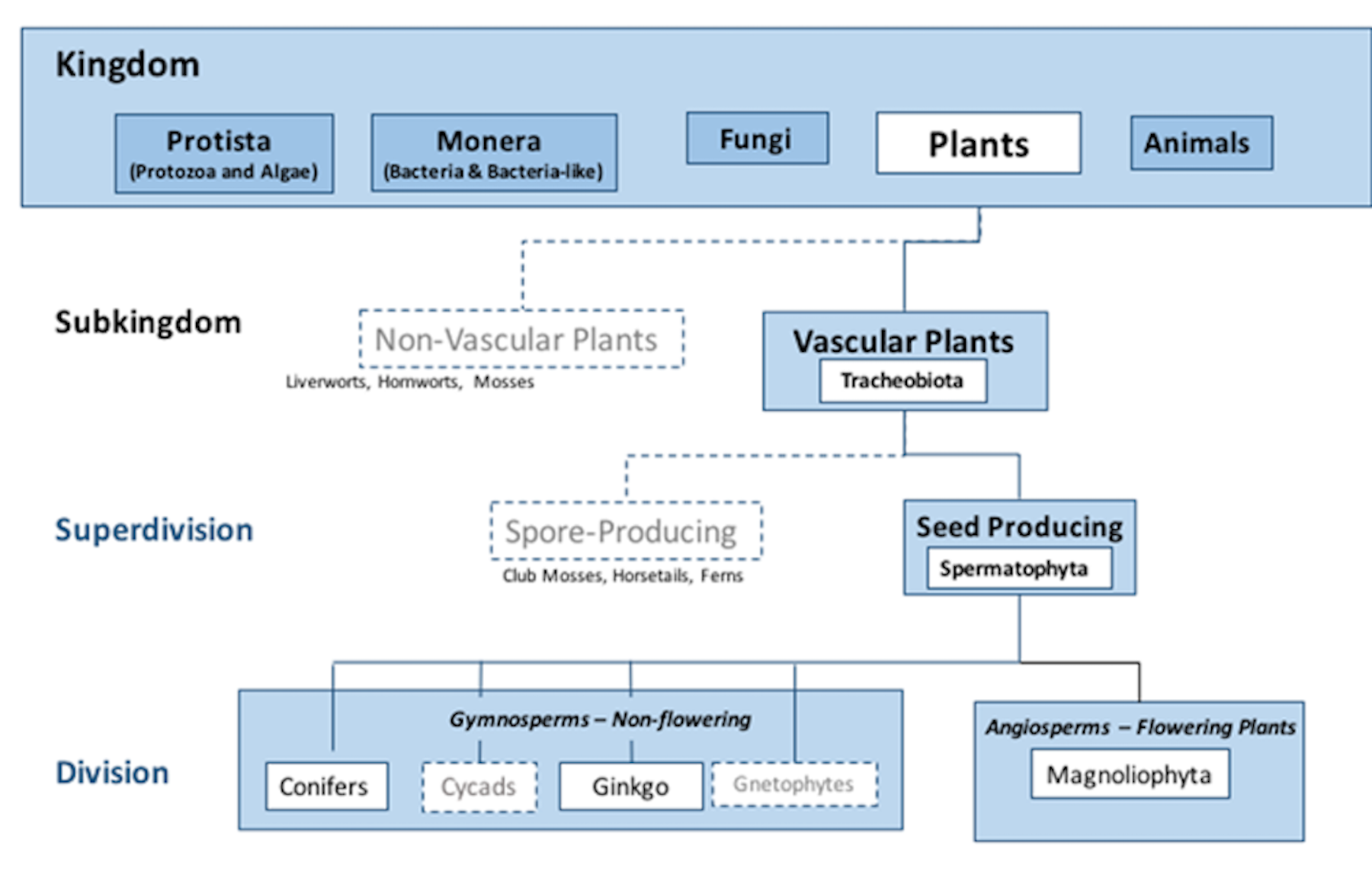

The various types of trees may be understood in terms of the related groupings (taxa) to which they belong and the similar characteristics that are shared within their group. All living things are classified into hierarchical categories based on shared characteristics. The contemporary method for classifying living things into taxonomies was developed by Carl Linnaeus in the 1700s. At that time, living things were grouped based on observable forms and structures. Over time classifications have changed as knowledge and scientific tools change. DNA analysis, chromosome numbers, isozymes (proteins produced by particular genes), and nucleic acids sequences are examples of new techniques used in more recent years. Different taxonomists may draw different conclusions. Taxonomies from different sources may not completely agree in their terminology. Taxonomy information in this section is based on the classification scheme for plants as used by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Plant Database.[3] See Table 5-1.

The utility of the various taxonomy levels varies with the kingdom. For example, when studying insects significant characteristics are captured in orders.

Academic researchers deal with division, class, and order. These classification levels are most frequently impacted by the use of current scientific methods. For practical applications the focus tends to be on the family level and below. In contrast to division, class, and order, plant families are quite stable.[4] Families are important in gardening because plants within a given family generally share comparable cultural requirements and similar insect and disease problems. Pest management and cultural techniques are frequently discussed at the family level. Plants within some families may share common characteristics in appearance, leaf shape, seed form and structure, and growth habit. Other families may exhibit much more diversity. The Digital Atlas of Virginia Flora primarily focuses on the family level and below.[5]

Table 5-1 Taxonomy schema for plants

| Classification Division | Distinguishing Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Kingdom | Structural Organization (Single cell/multi-cell, whether nucleus is enclosed in a membrane) Method of Nutrition (Absorb, photosynthesize, or ingest food) |

| Subkingdom | Whether plants have a vascular system or not |

| Superdivision | Whether plants produce seeds or spores |

| Division | Whether seeds are naked (non-flowering) or encased (flowering) |

| Class | Areas of commonality based on important, more detailed, similarities within subsets of each division. |

| Subclass | Further sub setting into groups with like characteristics. |

| Order | Further sub setting into groups with like characteristics. All names for orders end in “ales.” |

| Family | A group of individuals directly related by descent from at least one common ancestor. (Dictionary of Forestry [7] )

Based on commonality of distinguishing characteristics especially those inherent in their reproductive structures (flowers, fruit, seed). All names for plant families end in “aceae.” |

| Genus | Groupings based on commonality in fundamental traits such as flowers, fruits and sometimes, roots, stems, buds and leaves. Members of a given genus have more characteristics in common with each other than other groupings within the same family. |

| Species | A group of similar interbreeding individuals sharing a common morphology (external and internal structure of plants), physiology and reproductive process. There is generally a sterility barrier between species or at least reduced fertility in interspecies hybrids. (Dictionary of Forestry [6] ) |

A note about the terms subkingdom and superdivision in Table 5-1: A common taxonomy categorization hierarchy is kingdom, phylum, division. Instead of phylum this chapter uses subkingdom and superdivision because it is at those levels that basic plant characteristics diverge.

The end result of the taxonomy of living things is a two-part scientific name composed of the genus and species and called the “binominal nomenclature.” The taxonomical classification of a given plant and even its binominal nomenclature may change as more is understood about a given plant.

Further detail within species is provided by variety, cultivar, and hybrid, as defined in Table 5-2. Note that while the terms in Table 5-1 are hierarchical, that relationship does not hold for these terms. A cultivar is a type of variety, not a subset. The hybrid could result from mating different varieties, cultivars, or species.

Table 5-2 Sub classifications below species

| Classification Division | Distinguishing Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Subspecies | A geographically isolated variant within a species. |

| Variety | A grouping within a species, usually not geographically isolated, having distinct, though often inconspicuous differences and breeding true to those differences. A variety may be naturally occurring, managed, or a hybrid. A category based on fewer correlated characters than are used to differentiate species or subspecies, given a Latin name preceded by "var." |

| Cultivar | A linage in a species that has been selected for a specific attribute and is distinct, stable, and uniform when propagated. Cultivars are usually propagated by asexual means, such as grafting, to preserve genetic makeup. |

| Hybrid | A cross between two species that results in a viable new plant. May occur in nature or artificially. |

An important grouping for trees occurs at the division level. At that point, plants are separated into gymnosperms (non-flowering plants that produce naked seeds not enclosed in an ovary) and angiosperms (flowering plants with seeds enclosed in an ovary).

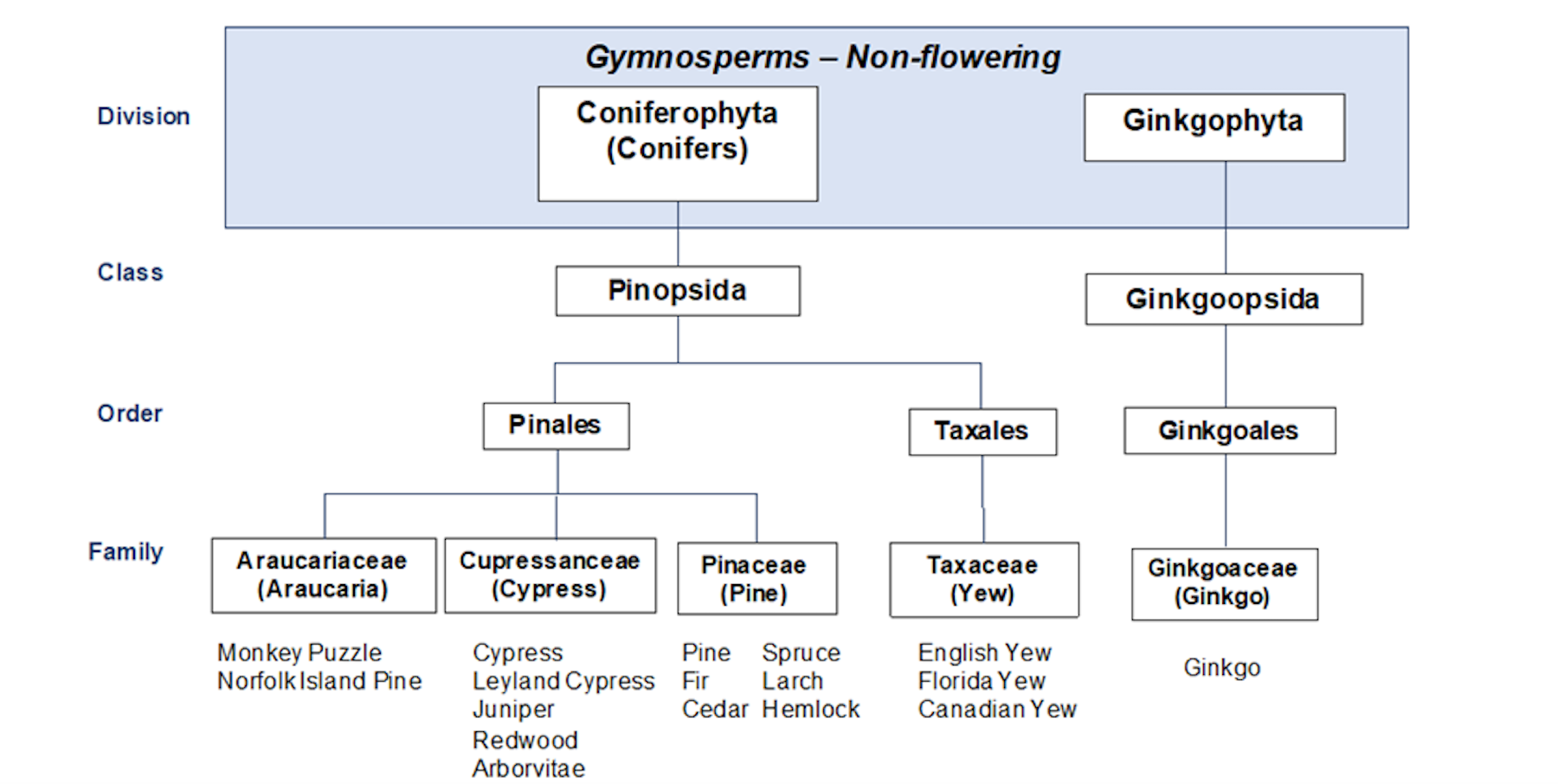

Gymnosperms include the Conifers, Cycads, Ginkgo, and Gnetophytes Divisions. The only Cycad native to eastern North America is a shrub native to Florida and SE Georgia. The only Gnetophyte in eastern North America is a shrub that grows in Texas and Oklahoma. Since our focus is trees, these two divisions are not addressed further. The taxonomy of Conifers and Gingko gymnosperms from division to family is provided in Figure 5-2.

The Pinales Order contains two additional families that are not addressed here because they do not include trees relevant in our area. It is interesting to note that the ginkgo tree is the only living species within the Ginkgophyta Division. The ginkgo has existed for over 200 million years and is considered a living fossil.

Several types of trees within the Pine Family have multiple cotyledons within their seeds and may be referred to as polycots.

All angiosperms are contained in the Magnoliophyta Division and have traditionally been subdivided into monocots and dicots. This has been a morphological classification, that is, the classification is based on the form and structure of the plants, such as the usual number of flower parts, the number of cotyledon (embryonic first leaves of a seedling) inside the seed, and additional related characteristics. Chapter Four discusses many of these characteristics in more detail.

- Monocots have a single seed leaf within the seed. Most monocot flowers have flower parts in sets of three, so that there may be three or six petals. Leaf veins are usually arranged in parallel. The vascular bundles of monocots vary in size and are scattered throughout the stem and, therefore, cannot form annual rings of hardened tissue, i.e. wood. This limits the strength of their stems. The only trees within the Monocot Class are palms (Arecaceae Family).

- Dicots, as traditionally defined, have two seed leaves with flower parts that usually occur in multiples of 4 or 5. Leaf veins are netlike. Vascular bundles are uniform in size and arranged in a ring around the stem of the plant. This enables dicot trees to form wood from annual rings of hardened tissue.

The scientific consideration of dicots has become more complicated due to recent advances, especially in the ability to evaluate plants based on DNA and also to study plants at a molecular level: this is called phylogenetic classification. This more recent research has modified the traditional monocot/dicot grouping for taxonomical purposes into monocot, eudicot, and basal angiosperms to better reflect the evolution of the plants. A distinguishing structural characteristic of eudicots is that their pollen grains have three grooves. The pollen of both monocots and basal angiosperms have only one groove. While this structural characteristic is observable, it is not observable by the naked eye as are the monocot/dicot characteristics discussed above and in Chapter Four.

Scientists now believe that the initial primitive angiosperms were dicots; monocots evolved out of that group. Monocots now account for about 22% of all plant species. Palms are the only major type of tree that is a monocot. Most of the remaining dicots evolved into eudicots.[6] Eudicots make up 75% of flowering species and contain the largest proportion of tree families. The remaining 3% of flowering species are considered basal angiosperms,[7] a group of the most primitive flowering plants. Magnolias, tulip trees, paw paws, and sassafras trees are basal angiosperms.

An illustrative taxonomy of angiosperm trees from division to family is provided in Figure 5-3. Note that the taxonomy of angiosperms includes an additional level of classification “subclass” not used in the gymnosperm taxonomy. The subclasses, orders, and families with relevant trees tend to be broader and more numerous than those levels in the gymnosperm taxonomy. Only one categorization line is shown for each relevant subclass.

Under the Dicots, the gray circle shows basal angiosperms; the yellow oval shows eudicots.

The monocots contain four additional subclasses that do not contain relevant trees. The dicots contain two additional subclasses for a total of six. One subclass (Asteridae) includes tree families and the other (Caryophyllidae) does not. There are many more orders and families with relevant trees that are not shown in table 5-3 It is good to remember that the focus here is just the trees. The angiosperms also contain very large numbers of shrubs, perennials, and annual flowers.

Angiosperm taxonomy

| Division | Angiosperms - Flowering Plants | Angiosperms - Flowering Plants | Angiosperms - Flowering Plants | Angiosperms - Flowering Plants | Angiosperms - Flowering Plants | Angiosperms - Flowering Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Monocots | Dicots | Dicots | Dicots | Dicots | Dicots |

| Subclass | Arecidae | Magnoliidae | Hamamelididea | Rosidae | Dilleniidae | Asteridae |

| Order | Arecales | Magnoliales | Fagales | Rosales | Malvales | Scrophulariales |

| Family | Arecalcaceae (Palm Family) | Magnoliaceae (Magnolia Family) | Fagaceae (Beech/Oak Family) | Rosaceae (Rose Family) | Tillaceae (Mallow Family) | Oleaceae (Olive Family) |

| Examples | Palm Palmetto |

Tuliptree Magnolia |

Chestnut Beech Oak |

Serviceberry Apple Plum Cherry Pears |

Hibiscus Basswood Linden |

Fringetree Ash Olive |

Tree Families

Tree families and trees discussed below were selected based on their prevalence in this area, economic/historical/ornamental value, environmental importance, and likelihood of problems. Given the large number of trees that are either native or have been planted in this region, the selection below is necessarily subject to modification based on one’s local experience.

The intent is to provide information on observable characteristics to help Tree Stewards in identifying trees and providing right plant/right place tree selection and care. The discussion focuses on observable and distinguishing, non-technical characteristics associated with a family, genus, and species. In general, the discussion does not go into scientific aspects that are not readily observable. One of the easiest tree guides to use (for native trees) is VDOF’s Common Native Trees of Virginia.[8]Except as noted, the black and white illustrations accompanying the family paragraphs are copied from this book, with kind permission from the Virginia Department of Forestry. They are the work of Juliette Watts of the US Forest Service.

The native growing range for trees indigenous to Virginia can be found in Common Native Trees of Virginia. For trees indigenous to North America, the native growing range is provided at the USDA Plant Database website.[9] Trees of Eastern North America also provides ranges.[10] The Digital Atlas of Virginia Flora website notes Virginia counties in which a given species has been observed.[11]

The stated number of genera and species in a family can vary based on the source of the information. This document uses the numbers provided in Trees of Eastern North America. Also, stated expected heights and diameters of trees vary based on the source of the information. For trees native to Virginia, this document uses the height and diameter provided in Common Native Trees of Virginia. For other trees, height and diameter is based on information in Trees of Eastern North America. The terms tall, medium, and short are applied to tree heights as follows: tall – 45 feet and greater, medium – 25-45 feet, short – 25 feet and under.

Gymnosperms

Cypress Family (Cupressaceae)

The Cypress Family is composed of cone-bearing plants with male (pollen) and female (seed) cones either on separate plants (dioecious) or on the same plant (monoecious). In most Cypress species, the seed cone is small and woody but some have small fleshy cones that look like berries. While some species may be deciduous, most members of the Cypress Family are evergreen with leaves that are either scale like or needle like. When needle like, the needles may cover the twig or be flattened and two-ranked (leaves arranged in two vertical columns on opposite sides of the stem). The bark is fibrous and furrowed and may be peeled off in long, thin strips. Generally, the wood contains resin, is aromatic, and is rot-resistant. Given its resistance to decay, the wood is frequently used for construction and fence posts.

There are 19 genera within the Cypress Family. Key representative genus and trees of interest in this area are discussed below.

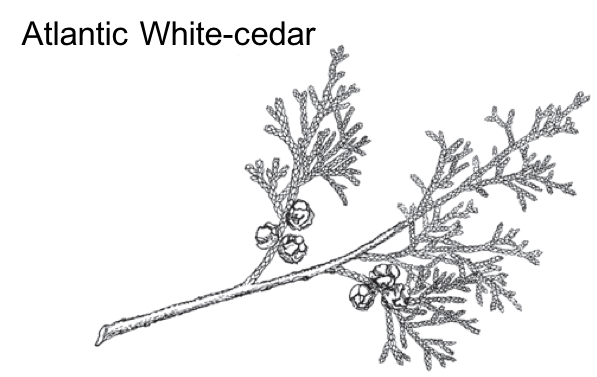

1. Genus ChamaecyparisSpach – False Cedar

The trees in this genus are sometimes referred to as false cedars or new world cedars to distinguish them from the true cedars in the Pine Family, discussed below. Common characteristics are:

- Tiny, scale-like leaves that overlap like shingles and form flat sprays like a fern.

- Distinctive, small cones that remain on the tree long after their seeds are gone.

- Aromatic wood.

The Atlantic White-cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides (L.) B.S.P.) is found in southeast Virginia and favors swampy habitats. It is generally of medium height with a 1 to 2 feet diameter trunk. It looks very similar to the more common eastern redcedar but the needles are blue-green with small, round (¼ “diameter) woody cones with a waxy grayish coating.

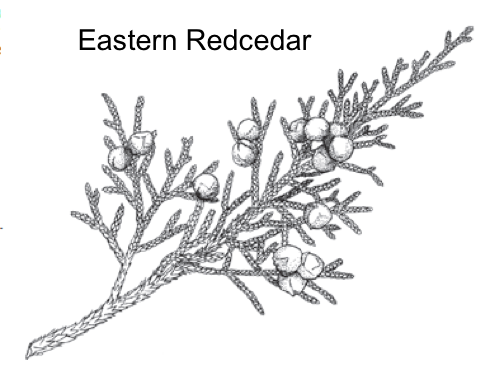

2. Genus Juniperius L. – Junipers – Junipers are evergreen, have scale-like leaves that are pointed and prickly, and have fleshy cones that look like berries. The genus contains many shrubs and some trees.

The most common juniper tree in our area is the Eastern Redcedar (Juniperus virginiana L.). With a medium height and a trunk of 1 to 2 feet in diameter, it is the largest and most tree-like of the junipers. The eastern redcedar grows throughout most of the eastern United States on a variety of soils and is able to thrive where few other trees are found. The fleshy, berry-like cones appear only on female trees. Cones are small, ¼ to 1/3 inch in diameter. Cones start out as green and turn blue when they mature. It is one of the longest-lived of North American conifers and has been known to live almost 800 years. Its aromatic wood is used to line closets and chests.

3. Genus Taxodium Rich. This genus contains three species of large trees that are extremely flood tolerant. The needle-like leaves, 0.2 to 0.8-inch-long, are borne spirally on the shoots, twisted at the base so as to appear in two flat rows on either side of the shoot. The seed cones are shaped like globes, 0.8 to 1.4 inches diameter. The male (pollen) cones are produced in pendulous racemes, and shed their pollen in early spring.

Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum) is the most familiar species within this genus. It is a tall, deciduous conifer with a trunk that can be as large as 3 to 6 feet in diameter. Needles occur flattened and two ranked on its twigs. The tree frequently naturally occurs near water and is considered the characteristic tree of southern swamps. Its unique characteristic is knobby wooden knees. The purpose of the knees is not known but are thought to provide additional oxygen to the plant. The tree generally does not produce knees in a non-wet environment.

4. Other

Other well know trees within the Cypress Family that Tree Stewards likely will want to be knowledgable of are:

- Arborvitae

- Leyland Cypress

- Cryptomeria

- Dawn Redwood

- Giant Sequoia

Pine Family (Pinaceae)

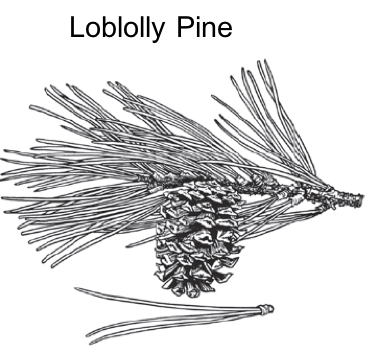

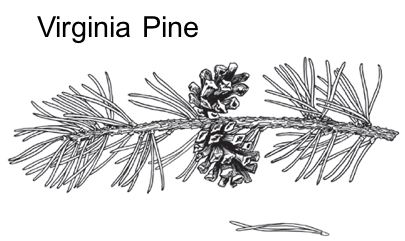

All members of the Pine Family are monoecious (both male and female parts on a given plant). The bark varies across the species. Leaves are either simple needles or needles occurring in bundles of 2-5. Cones are usually woody with many scales.

There are 9 genera in the pine family. Key representative genus and trees of interest in this area are discussed below.

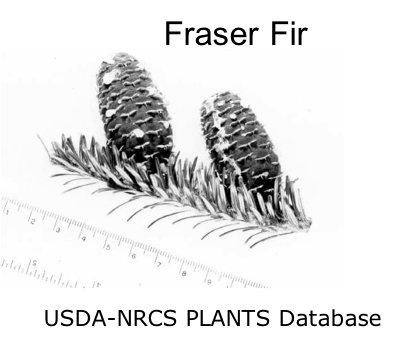

1. Genus Abies Mill. – Fir. Firs have needlelike leaves, arranged in a spiral but often appearing 2-ranked. The needles are generally soft to the touch. Firs live in regions that are covered in snow many months of the year, generally at elevations from sea-level to 6500 feet.

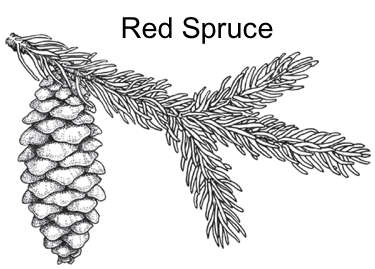

2. Genus Picea A. Dietr. – Spruce. Spruces look very similar to firs but have stiff, usually sharp-pointed needles. Their native habitat is mostly in the mountains at high altitudes.

Red Spruce (Picea rubens Sarg.) A tall tree with a trunk that could be 3 ft in diameter, the red spruce is found in small scattered areas at elevations above 4000 feet in the west of Virginia. Needles are ½ to 5/8 inches long, pointed and attached to the twig on tiny raised pegs. Cones are 1 ¼ to 2 inches long, light reddish-brown, and shiny with smooth edged scales. Cones drop their first winter. The wood is light, somewhat soft and elastic. Example uses are lumber, pulpwood, and musical instruments.3. Genus Pinus L. – Pine. Pines are evergreen trees with needle shaped leaves occurring in bundles of 2-5. Representative pines of interest are discussed below.

Virginia Pine (Pinus virginiana Mill.) A tall tree, somewhat smaller than the loblolly, with trunks of 12 to 14 inches in diameter. Needles are 1 ½ to 3 inches long, two needles in a bundle,. Needles are usually twisted. Cones are egg shaped, 1 ½ to 2 ¾ inches long. Cones mature in two years but stay on the tree several years before falling. The wood warps easily and is used for rough construction and paperpulp.

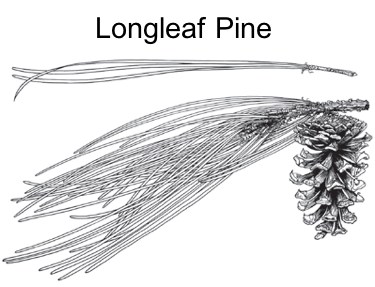

Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris Mill.) Tall with trunks of 2 to 2.5 feet. This tree has the longest needles and largest cones of any pine in the eastern part of North America. Needles are 8 to 15 inches long with three in a cluster. Cones are cylindrical, 6 to 10 inches long. Cones mature in two years and drop from the tree after releasing their seeds in the fall.

The longleaf seedling appears to be a clump of grass and only develops a stem after several years. The tree prefers to grow in acidic, infertile soils and likes sandy soils. It is very adapted to fire, generating seedlings best when fire burns off the fallen needles, clearing the understory but not harming the mature trees.

Before European settlement, longleaf pines dominated the coastal plain from Virginia to Texas. Today they are found only in isolated sections. Heavy cutting of the trees for commercial use, combined with fire suppression, has lead to significant reduction of the species. Restoration efforts are ongoing in Virginia. American’s Longleaf Restoration Initiative (ALRI) was formed in 2007 to restore longleaf pine ecosystems. It is lead by the USDA Forest Service, Department of Defense, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service with participation from various public and private organizations across nine southern states.[14]

Other well known trees within the Pine Family that Tree Stewards likely will want to be knowledgeable of are:

- Shortleaf Pine

- Eastern White Pine

Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris Mill.) Tall with trunks of 2 to 2.5 feet. This tree has the longest needles and largest cones of any pine in the eastern part of North America. Needles are 8 to 15 inches long with three in a cluster. Cones are cylindrical, 6 to 10 inches long. Cones mature in two years and drop from the tree after releasing their seeds in the fall.

The longleaf seedling appears to be a clump of grass and only develops a stem after several years. The tree prefers to grow in acidic, infertile soils and likes sandy soils. It is very adapted to fire, generating seedlings best when fire burns off the fallen needles, clearing the understory but not harming the mature trees.

Before European settlement, longleaf pines dominated the coastal plain from Virginia to Texas. Today they are found only in isolated sections. Heavy cutting of the trees for commercial use, combined with fire suppression, has lead to significant reduction of the species. Restoration efforts are ongoing in Virginia. American’s Longleaf Restoration Initiative (ALRI) was formed in 2007 to restore longleaf pine ecosystems. It is lead by the USDA Forest Service, Department of Defense, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service with participation from various public and private organizations across nine southern states.[15]

Other well known trees within the Pine Family that Tree Stewards likely will want to be knowledgeable of are:

- Shortleaf Pine

- Eastern White Pine

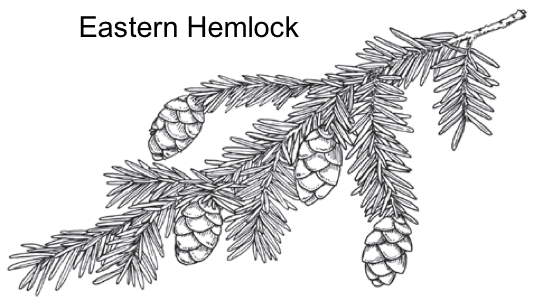

4. Genus Tsuga – Hemlock. Hemlock needles are arranged in a spiral on the twig but appear to be 2-ranked and flattened. There are only 7 species worldwide with only 2 species, Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) and Carolina Hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana), in the Virginia/North Carolina area. When crushed the foliage smells a bit like the European native poisonous herb called hemlock and thus the name.

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) A tall tree with a trunk 2 to 4 feet in diameter, the eastern hemlock is found primarily in the western portion of Virginia. Needles are short, 1/3 to 2/3 inch long, with two pale lines on the lower surface. The ¾ cones grow on the tip of branchlets.21

5. Genus Cedrus – True Cedar. True cedars are native to the mountains of the western Himalayas and the Mediterranean region and are adapted to mountain climates.[16] They have rather short evergreen needles occurring primarily in dense clusters at the end of short woody pegs. This tufted arrangement of needles is only seen in true cedars and larches. Large, barrel-shaped cones sit on the top of branches and have thin scales that fall apart when mature. They are generally very large (tall and wide) trees and are planted in parks and public areas in the United States and especially in the Pacific Northwest. Most true, old-world cedars seen in North America are ornamentals.

Deodar Cedar (Cedrus deodara) is frequently seen in this area and is rumored to be naturalized in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Its needles are 1-2 inches long, grouped in clusters with individual needles on the branch tips. There is a noticeably droop in the branch tips and leader.15

Other true cedars include the Atlas Cedar (Cedrus atlantica) and Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani). Both trees have needles about 1inch long with a stiff branching habit.

Angiosperms

While all angiosperms flower, not all flowers are notable. This is especially true for trees that are angiosperms.

Birch Family (Betulaceae)

The Betulaceae family includes birches (Betula), alders (Alnus), hornbeams (Carpinus), and hazels (Corylus). The trees are deciduous and have simple, alternate leaves that are generally thin with serrated edges (saw-like teeth) and pinnate veins (major veins branching off from a central vein). The trees are monoecious with male and female catkins forming on the same plant. A catkin is an elongated cluster of single-sex flowers bearing scaly bracts, usually lacking petals.

There are 6 genera in the Birch Family. Key representative genus and trees of interest in this area are discussed below.

1. Genus Betula – Birch. Birches usually have smooth bark, dark brown to silvery white, that often peels into plates or papery layers. Trees often have several trunks.

River Birch (Betula nigra L.) is the only birch native to the Coastal Plain in the southeastern United States. It can be a tall tree and is often divided into several trunks. The trunks may be 1 to 3 feet in diameter. The bark peels back in papery layers. The leaves are 1 ½ to 3 inches long with an oval to triangular shape and doubly serrated edges. The wood is quite hard and close-grained but the tree is seldom harvested. It is commonly planted for erosion control situation such as stream bank restoration and is frequently used as an ornamental tree in home yards.

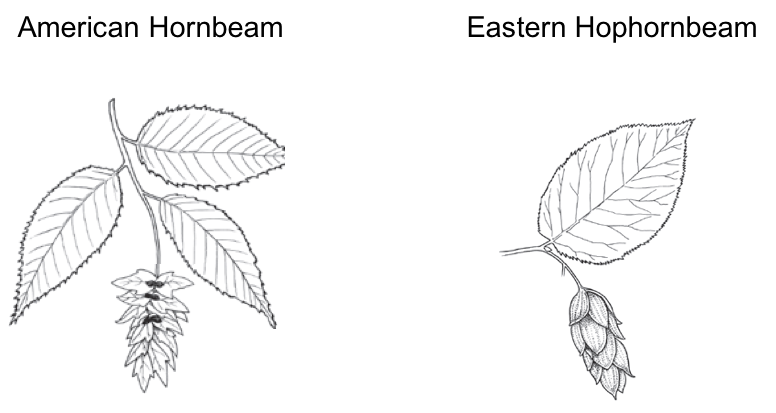

2. Genus Carpinus – Hornbeams and Genus Ostrya – Hophornbeam.

The American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana Walt.) and Eastern Hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana (P. Mill) K. Koch.) are both native in this area. While they are very similar and both belong to the Birch Family, they belong to different genera. Both are small trees growing 20 to 30 feet and can have a single trunk or multiple trunks. Both trees have leaves that are alternate, simple, 2 to 4 inches long with doubly toothed edges. The leaves of the American hornbeam are oval and long-pointed while the leaves of the eastern hophornbeam are oblong with narrow tips. The trunk of the American hornbeam is smooth and rippled, resembling well-defined muscles. This leads to alternate common names of ironwood or musclewood. The fruits of the American hornbeam are 4 to 6 inch hanging clusters of slightly folded, 1 inch, 3-lobed leafy bracts; each bract contains a ⅓ inch ribbed nutlet. These clusters somewhat resemble the samaras (helicopter seeds) of maples. However, the hophornbeam has fruits hanging in clusters of leafy, oval, papery sacs 1½ to 2½ inches long, with each sac containing a 1/4 inch nutlet. These clusters of papery sacs resemble hops and thus the name Hophornbeam.

The wood of both trees is strong and durable but is seldom harvested.

Bean or Pea Family (Fabaceae)

The Fabaceae Family is the third largest plant family and contains approximately 730 genera. More than 45 genera of trees exist north of Mexico across North America. All members have compound leaves, mostly pinnately or bipinnately compound. However, the leaves of some species, such as the redbud, are unifoliate, that is they are theoretically compound but have only one leaflet and therefore appear to have a simple leaf. The unifying feature of the family is that the fruit is a legume, that is multiple seeds reside in a pod that opens along two sides. Roots often have nitrogen-fixing bacterial nodules. This document addresses one genus and two species in other genera within the Fabaceae Family.

1. Genus Gleditsia – Locusts. Locusts are medium height, single trunk trees with pinnate or bi-pinnate compound leaves. The compound leaves alternate and within the compound leaf, leaflets also alternate. A distinguishing characteristic is thorns that occur on the trunk and/or branches. Fruits are flattened legume pods with one to multiple seeds. Two species are native to North America.

Honey Locust (Gleditsia Triacanthos L.) The leaves are pinnately compound, 5 to 8 inches long, with 15 to 30 leaflets. However, the leaves can also be bipinnately compound with 4 to 7 pairs of minor leaflets. Leaflets are elliptical and ½ to 1 ½ inches long. Trunk, large branches and twigs have branched thorns that are strong and sharp. Small greenish-yellow flowers are fragrant and appear on 2 to 3 inch hanging clusters in late spring. The seed pod is 6 to 8 inches long and flattened. The pod matures in late summer and early fall, becoming dry and twisted. Seeds are oval, dark brown and 1/3-inch-long with multiple seeds in each pod. Because the wood is hard, strong, and moderately resistant to decay, it is sometimes used for fence posts and crossties. The tree may be planted for erosion control and windbreaks. Thornless varieties are available and are commonly chosen for planting in urban landscapes.

2. Other Genera

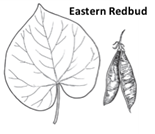

Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis L.) is a short tree, frequently multi-stemmed, that grows as an understory tree generally at the edge of a forest. It is one of the most common ornamental trees. In spring, it is covered with very small (½ inch) pink to purple flowers that resemble the flowers of a pea. The flowers occur in clusters along the twigs and small branches and appear before the leaves. Leaves are alternate, heart shaped, and smooth edged, 3 to 5 inches long and wide. While the leaves appear to be simple, they are an example of the infamous unifoliate. Although the wood is heavy and hard, it is not strong and has little commercial value.

Mimosa (Albiziz julibrissin Durazz) is a lovely small tree with smooth gray-brown bark. It was introduced from Asia in the late 18th century. The leaves are alternate, bi-pinnately compound, 10 to 20 inches long with a feathery appearance reminiscent of ferns. Fragrant flowers appear in the form of showy pink fluffy heads in mid to late summer. The fruit is a flat pod, 5 to 6 inches long, and turns a light brown. The single trunk is short, sending out branches at a low height and spreading into a wide V-shape crown that makes it an excellent climbing tree for children. Unfortunately, the seeds germinate easily across a wide range of conditions making the mimosa far too good at reproducing itself. It is treated as invasive and commonly considered a trash tree. So sad.

Other trees in the Fabaceae Family that the Tree Steward may find interesting include:

- Yellowwood

- Black Locust

- Kentucky Coffeetree

- Golden Chain Tree

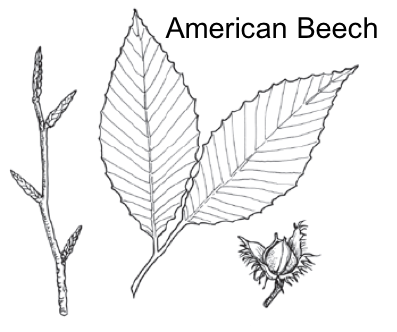

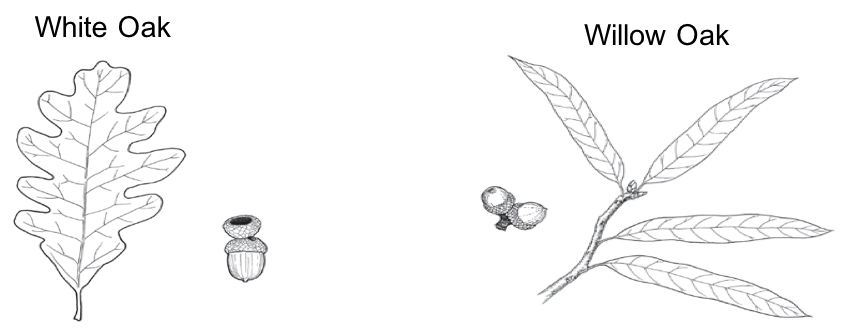

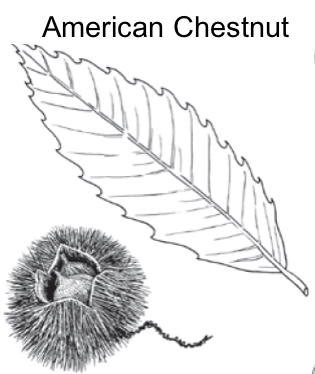

Beech or Oak Family (Fagaceae)

The Fagaceae Family contains deciduous and evergreen woody plants with simple leaves arranged alternately. The leaves may have entire, toothed, or deeply lobed leaf margins. Flowers are typically unisexual with male and female flowers appearing on the same plant (monoecious) in catkins (elongated cluster of highly reduced unisexual flowers). Fruits are nuts within a scaly or spiny cap.

There are 9 genera in the Beech/Oak Family. Key representative genus and trees of interest are discussed below

1. Genus Fagus – Beech. Beeches have smooth bark that is either silvery gray or blue-gray, though some species develop shallow furrows and ridges. Leaves are simple, elliptic or ovate, with margins that are bluntly or sharply toothed. The leaves have lateral veins that are parallel and terminate in the tip of a marginal tooth. The fruit is two nuts in a four-valved prickly capsule. Beeches are tardily deciduous trees. Many have a tendency to retain their leaves in a dry, lifeless state through the winter, especially when young.

2. Genus Quercus – Oak. Though the Mid-Atlantic representatives of the genus are typically deciduous, many evergreen species occur throughout the world’s warmer temperate and tropical regions. There are more local species, at least 16, of oak than any other genus.[17]The fruit of all oaks is the familiar acorn which is botanically identified as a nut covered by a cap of scales. Any plant that produces an acorn is an oak. The size and shape of the acorn and its cap is specific to the species of oak. The leaves are arranged alternately and vary in shape. Many are conspicuously lobed, but others have simple leaves without lobes. The bud scales overlap and most oaks feature a cluster of buds at the terminal end of each stem.

Oak wood is heavy, strong, hard, close-grained and durable. It is used for lumber, furniture, and flooring.

The majority of oak species are placed in either the Red Oak group or the White Oak group. Red Oaks have a bristle on the tip of their lobes and their acorns require two years to ripen. White Oaks do not have bristles. Their acorns ripen in a single season and are sweeter (have less tannin) than acorns from trees in the Red Oak group. White Oaks generally are slower growers than Red Oaks. The Sawtooth Oak is neither in the Red or White group but is considered an intermediary between the two groups.

White Oak (Quercus alba L.) is the most common oak in Virginia forests. It is a tall tree with a trunk that can be 3 to 4 feet in diameter. Leaves are alternate and simple, 4 to 7 inches long, with 7 to 10 rounded lobes. The sinuses between the lobes may be shallow to deep, almost reaching the midrib; this can give the leaf a very different appearance even among trees of the same species. The acorn is light chestnut brown, ¾ inch long, with a bowl-shaped cap that covers ¼ of the acorn. The cap detaches at maturity. The wood is close-grained, strong, and durable. Uses include furniture, flooring, and fuel. The wood is well suited for whiskey and wine barrels because it is highly water-tight due to the presence of a substance called tyloses in the wood vessels.

Willow Oak (Quercus phellos L.) is long lived, fast growing, and frequently planted in public spaces. The tree has an erect trunk that is medium to tall in height with a diameter of 1 to 2.5 feet, sometimes considerably wider in the taller specimens. Leaves are alternative, simple, and narrow oval (lanceolate) with a bristle tip, making them members of the Red Oak group. The acorn is small (¼ to ½ inches) and tan. The cap covers ¼ of the acorn nut and is flat, thin, and scaly. The wood is heavy and strong, but coarse-grained. It is used for rough construction and pulpwood.There are many oak species. Examples include:

- Southern Red Oak

- Northern Red Oak

- Swamp Chestnut Oak

- Live Oak

- Sawtooth Oak

- Water Oak

- Overcup Oak

- Scarlet Oak

- Pin Oak

3. Genus Castanea – Chestnut. Chestnuts have alternate leaves with bristle-tipped marginal teeth and conspicuous parallel lateral leaf veins. The trees produce large, sweet, edible fruit. The nuts are enclosed in a spiny, prickly capsule that may contain up to three nuts. There are 4 native species in North America. Of particular note is the greatly missed American chestnut.

American Chestnut (Castanea dentate) used to be a tall tree that was a dominant species in forests in much of Virginia. Trunks could be quite large with diameters up to 4 feet. In the early 1900s chestnut blight was introduced into eastern North America. By 1940 the chestnut had disappeared as a major tree in American forests. Today the plant can be found as sprouts from the stumps of dead American chestnut trees. The sprouts may get up to 20 feet in height and may live as long as 40 years. They do not produce fruit.

Another common tree in the Chestnut Genus is Allegheny Chinkapin, Castanea pumila.

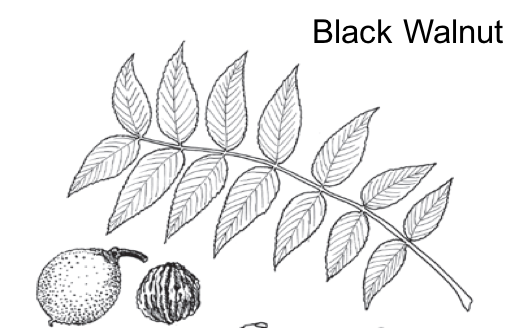

Walnut Family (Juglandaceae)

The Juglandaceae Family contains mostly trees and has 13 native species in eastern North America plus three nonnatives. All members have pinnately compound leaves and are usually odd-pinnate, that is they have a terminal leaflet at the end of the leaf. While the compound leaves are alternate; within the compound leaf, the leaflets are opposite. Flowers are tiny. The fruit presents itself as a nut surrounded by a husk that has developed from the fruit wall. The seed is large, oily, and often edible. Nuts mature late summer to fall. This document addresses two genera.

1. Genus Juglans – Walnut. The leaves of walnut trees usually have a spicy scent. Twigs are covered with hairs that have an enlarged gland at the tip. The fruit is shaped like a globe or ovoid surrounded by a green husk that turns black as it dries and does not split. In addition to providing edible nuts, walnuts provide dyes and lumber used in furniture and cabinets.

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra L.) can be medium to tall in height with a diameter of 2 to 3 feet. Leaves are odd-pinnately compound. The terminal leaflet is often much smaller than the side leaflets. Frequently the terminal leaflet is lost so that the compound leaf appears even-pinnate. The compound leaves are long, 12 to 24 inches, with 10 to 24 leaflets. The leaflets are 3 to 3.5 inches long, finely toothed, with a narrow oval shape tapering to a pointed tip (lanceolate). Yellow-green flowers appear in spring with male flowers appearing in 2.5 to 5.5 inch catkins and female flowers on short spikes at the tip of branches. The nuts are encased in thick green husks that do not split. The husks turn black as they dry. The nut inside has a black shell that is wood-like, thick and furrowed. The nut meat is difficult to extract from the shell but has a delicious and distinctive taste when added to baked goods. The heartwood is of superior quality and value and is used for fine furniture and cabinetwork. Sometimes one hears the statement, “Nothing grows under walnut trees.” That is not quite true. Black walnuts secrete a toxic chemical called juglone that prevents some plants from growing near them. Examples of susceptible plants include azalea, rhododendron, mountain laurel, blackberry, blueberry, apple, tomato and potato.

- English Walnut

- Butternut

2. Genus Carya – Hickories. Each compound leaf has 3 to 21 leaflets arranged opposite each other with a conspicuous terminal leaflet. The leaflets are usually hairy although sometimes the hairs only occur on the axis of the vein on the lower surface. The fruit is a nut enclosed in a husk that may be either thick or thin. In contrast to members of the Juglans genus, whose husks do not split, husks of hickories split when mature.

Pecan (Carya illinoensis (Wangenh) K. Koch) is a tall tree with long compound leaves usually having from 9 to 15 leaflets, 12 to 18 inches long. Occasionally there may be only 5 to 7 leaflets. The leaflets are relatively long and narrow oval-shaped tapering to a pointed tip (lanceolate) with toothed margins. The base of the leaflet is often asymmetric. Twigs are fuzzy, especially when young. Fruits are husk-covered nuts, 1 ½ to 2 inches long. Sutures (lines of fusion) are narrowly ridged and separate the husk into four sections. The thin husk splits to the base revealing a dark brown, ellipsoid nutshell. The kernel is edible and is used in baking or roasted as a snack.

Mockernut Hickory (Carya alba Nutt) (formerly Carya tomentosa Nutt.) is a medium to tall tree. Compound leaves are 9 to 14 inches long with 7 to 9 finely toothed leaflets of differing sizes and obovate-elliptic in shape. The leaflet on the tip is the largest. The lowest pair of leaflets are the smallest. Occasionally there are only 5 leaflets. Leaflets are dark green on the top with sparse hairs. The underside is orange-brown and hairy. Leaves are aromatic when crushed. The fruit is an oval, husk-covered nut. The husk splits almost to the base when mature forming four sections. The nut is 1 ½ to 2 inches long with a very thick shell and is sweet. The hard, strong wood has a number of uses to include tool handles, furniture, charcoal and smoking of meats.

Bitternut Hickory (Carya cordiformis (Wangenh.) K. Koch) is a medium height tree. The compound leaves have 7-9 finely toothed leaflets, with a narrow, long oval shape tapering to a pointed tip (lanceolate). The top of the dark yellow-green leaflet may be hairless or hairy. The underside is paler and covered with resinous scales. The 4-ribbed nutshells have a thin husk and are 1 ¼ inches long, round and slightly flattened. Nutshells split from the middle to a sharply pointed tip. The nuts are bitter. The hard, strong wood has a number of uses to include tool handles, furniture, flooring, and smoking of meats.

Other trees in the Carya genus that the Tree Steward may find interesting are:

- Shagbark Hickory

- Pignut Hickory

Magnolia Family (Magnoliaceae)

“The Magnolia Family is an ancient family, dating back more than 100 million years in the fossil record. The flowers have retained some ancestral characteristics, where the sepals, petals, stamen, and pistils are arranged in a spiral on a cone-like receptacle, rather than in concentric rings as they are in most other plant families.”[18]

Trees in the Magnolia Family have showy flowers that are white, cream, or yellow tinged. The pistons in the middle of each flower grow into a cone-like structure that contains the seeds.

There are two tree genera of significance to Virginia in the Magnolia family. Both genera and selected trees of interest are discussed below

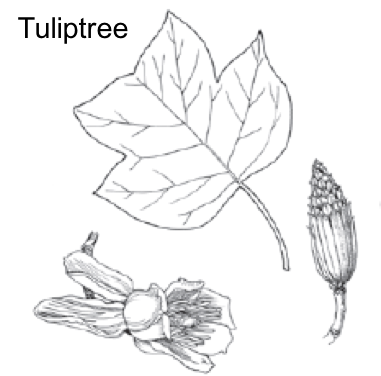

1. Genus Liriodendron – Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera) is the only species in this genus. Tuliptree, aka tulip poplar, yellow poplar, is one of the most common trees in Virginia forests and one of the largest and most valuable hardwood trees in the United States. It is also one of the easiest to identify. The large leaves (4 to 6 inches) are shaped like tulips and are the only tree leaf that is concave in the middle leaf top. In spring, after the leaves appear, the tree produces tulip-shaped flowers that are creamy yellow with blotches of orange and measure 2 to 3 inches across. The pistils in the center of the flower evolve into a 3” cone-like cluster of woody, wing-like seeds. The seeds break away in the fall but leave behind a spike that resembles wooden flowers. In the winter after the leaves fall, the tree can be identified by these wooden flowers. The tree has a straight trunk and is one of the tallest hardwood trees in the forest, typically growing to 90 to 110 feet. This fast-growing tree produces light, soft wood that is easily worked. Uses for the wood include lumber, plywood, paper pulp, and fuel.

2. Genus Magnolia – Magnolia. Leaves are simple, typically elliptical, obviate, or ovate. Most leaf edges have entire margins, that is the edges are smooth without teeth or lobes; but some have slightly undulating edges.[19]The top of the leaf is deep green with the backside a lighter green or somewhat silvery color. Leaves can be quite large on some species and are deciduous or persistent depending on the species and location. Magnolias have solitary flowers that are showy, creamy white and often very fragrant. The center of the flower matures into a cone-like structures containing red, pink, or orange-coated seeds. The seeds can separate from the cone-like structure to dangle on a threadlike attachment.

Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) has thick leathery very stiff leaves with brown on the underside. Leaves can measure 4 to 12 inches long and 2.5 to 4 inches wide. The tree is evergreen with a pyramidal shaped crown. The flowers can be 6 to 10 inches wide. It is probably one of the most recognizable trees in Virginia.

Sweetbay Magnolia (Magnolia virginiana) may have a single trunk or multiple trunks. Leaves are elliptical with smooth edges and a blunt point and measure 4 to 6 inches long. They are shiny bright green above and pale or whitish below and not as thick as the leaves of the Southern Magnolia. When crushed they release a pleasant, spicy odor. The tree sheds its leaves later than other trees in the fall. Further south it may be almost evergreen. The white flowers are smaller than those of other native magnolias and measure 2 to 3 inches across. The wood is soft and not of significant commercial value. The tree is often grown as a landscape tree.

Other well know trees with which Tree Stewards likely will want to be familiar are:

- Star Magnolia

- Saucer Magnolia

- Cucumber Magnolia, aka Cucumber Tree

- Fraser Magnolia, aka Umbrella Magnolia

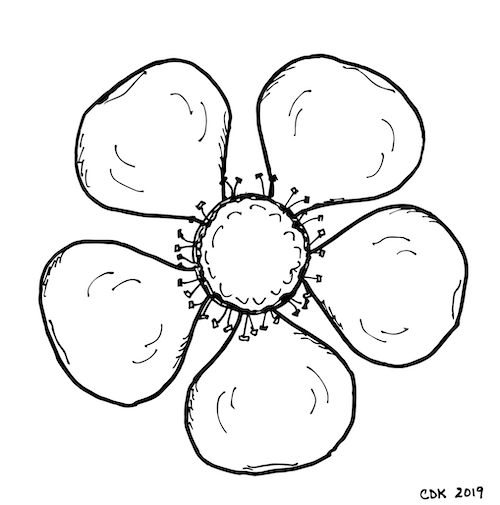

Rose Family (Roseaceae)

The Roseaceae Family contains a variety of fruits of which many are edible. The fruits vary from fleshy to false fruits (fruits not formed from the ovary), dry seeds, capsules, or follicles. Leaves are alternate but diverse in shape. They may be simple or compound with edges that are entire, toothed, or lobed. Plants in the Roseaceae Family have flowers that most commonly have five petals and five sepals. In rare cases the flowers may have three to ten petals. Flowers generally have a fuzzy looking center surrounded by stamens. Stamens are usually numerous and occur in whorls, with a minimum of five and additional stamen occurring in groups of five.

Genus Rosa – Rose. Includes 105 species of roses. Most roses have more than five petals, a condition known as doubling. Doubling occurs when some or all of the stamens become modified to look like petals. These petal-like structures are called petaloids. Examples of species roses include Bourbon rose, Cherokee Rose, damask rose, tea rose, and climbing rose.

Genus Fragaria – Strawberry

Genus Rubus – Raspberry, blackberry, boysenberry

2. Almond Subfamily (Amygdaloideae)

- Plum group: Fleshy fruits are drupes, meaning they have an outer skin covering a fleshy layer surrounding a stony center that contains the seed. Fruits have an indentation that appears to be a seam down one side. Two genera belong to the plum group.

Genus Prunus – Plums and Relatives. Familiar plants include plum, cherry, apricot, peach, nectarine, and almond.

- Apple group: Fleshy fruits are pommes, meaning they have a compound ovary and multiple seeds. The bottom of the fruit contains a five-pointed star that is the remains of the flower. Twelve genera belong to this group.

Genus Malus – Apple and crabapple

Genus Pyrus – Pear and ornamental pear

Genus Amelanchier – Serviceberry

Other well know trees in the apple group with which Tree Stewards likely will want to be familiar are spread across various other genera and include:

- Quince

- Flowering Quince

- Photinia

- Pyracantha

- Hawthorn

- Mountain Ash

Willow Family (Salicaceae)

The Salicaceae Family includes 50 to 60 genera, five genera occur in North America of which three are native. Most members have alternate, simple leaves with a toothed edge. Stipules are often present. A common characteristic relates to their flowers. The flowers do not have petals and sepals are greatly reduced or absent. Flowers are borne on catkins that appear with or before the emergence of new leaves. Trees are unisexual, that is male and female parts occur on separate trees. Plants in this family have a strong affinity to water and tend to prefer moist sites. Plants in the Willow Family contain varying amounts of organic compounds (glycosides, populin, salicin, and methyl salicylate) which provided the basis for aspirin. The compounds are strongest in the inner bark, but also present in the leaves. This document considers two genera that includes poplars, cottonwoods, aspen, and willows.

1. Genus Populus – Poplars, Cottonwoods, Aspen. Trees are deciduous and medium to tall height. The bark is smooth and pale on young trees but on older trees the bark can become darker, thick, and deeply furrowed. As characteristic of the family, the leaves are alternate, simple, and toothed. In addition to these common family characteristics, leaves in this genus are heterophyllous, that is leaves from different parts of the twig can have different forms. There are seven species in eastern North America.

Eastern Cottonwood (Populus deltoids Bartr. Ex Marsh) is a tall tree that can be 3 to 4 feet in diameter. It characteristically lives along river borders, floodplains, and other moist, well-drained sites. Leaves are triangular and somewhat heart-shaped with pinnate veins. Twigs are yellowish and have a bitter aspirin taste. The fruit is a small capsule, ¼ inch long, that appears on female trees and splits to release many tiny, cottony seeds. The wood is soft and lightweight and often warps when dried. Example uses are for baskets, rough lumber, fiberboard, plywood, and paper pulp.

Other trees in the Populus genus that the Tree Steward may find interesting include:

- Bigtooth Aspen

- Lombardy Poplar

- Quaking Aspen

- White Poplar (invasive)

2. Genus Salix – Willow. Many of the willow species have leaves that are lanceolate, long, narrow, with a pointed tip. In addition to the flowers having no petals, they also have no sepals. The willow contains salicylic acid and is known for its aspirin-like ability to treat headaches, fevers, and inflammations of the joints. There are about 30 tree-like species in eastern North America occurring from sea-level to above the timberline.

Weeping Willow (Salix babylonica L.) is a generally small tree that can reach 40 to 50 feet. The tree is thought to have originated in China. While it no longer occurs in the wild, the weeping willow is naturalized in many places in eastern North American. It needs to grow in a moist area. The crown is usually rounded with long, flexible branches that gracefully droop toward the ground. The fruit is a one inch long cluster of light brown valve-like capsules, containing many fine, cottony seeds, and maturing in late May to early June.

Other trees in the Salix genus that the Tree Steward may find interesting include:

- White Willow

- Black Willow

- Pussy Willow

Soapberry Family (Sapindaceae)

The Sapindaceae Family contains approximately 150 genera of trees, shrubs, and woody vines distributed primarily in tropical and subtropical areas, but extending into the north temperate region. The observable characteristics such as leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds vary considerably across the family. At various times during the 20th century, there was discussion in the scientific community about the relation of the Aceraceae (Maple) and Hippocastanaceae (Horse Chestnut) Families to Sapindaceae. In the 21st century taxonomists officially moved maples and buckeyes/horse chestnuts into the Soapberry Family. This move was based on DNA evidence and phylogenetic theory, i.e. the theory of the evolution of a genetically related group of organisms. While this move is generally accepted, the USDA Plant Database does not reflect this change and continues to show Aceraceae as the Maple Family and Hippocastanaceae as the Horse Chestnut Family. This document presents maples and buckeyes/horse chestnuts as genera within the Soapberry Family.

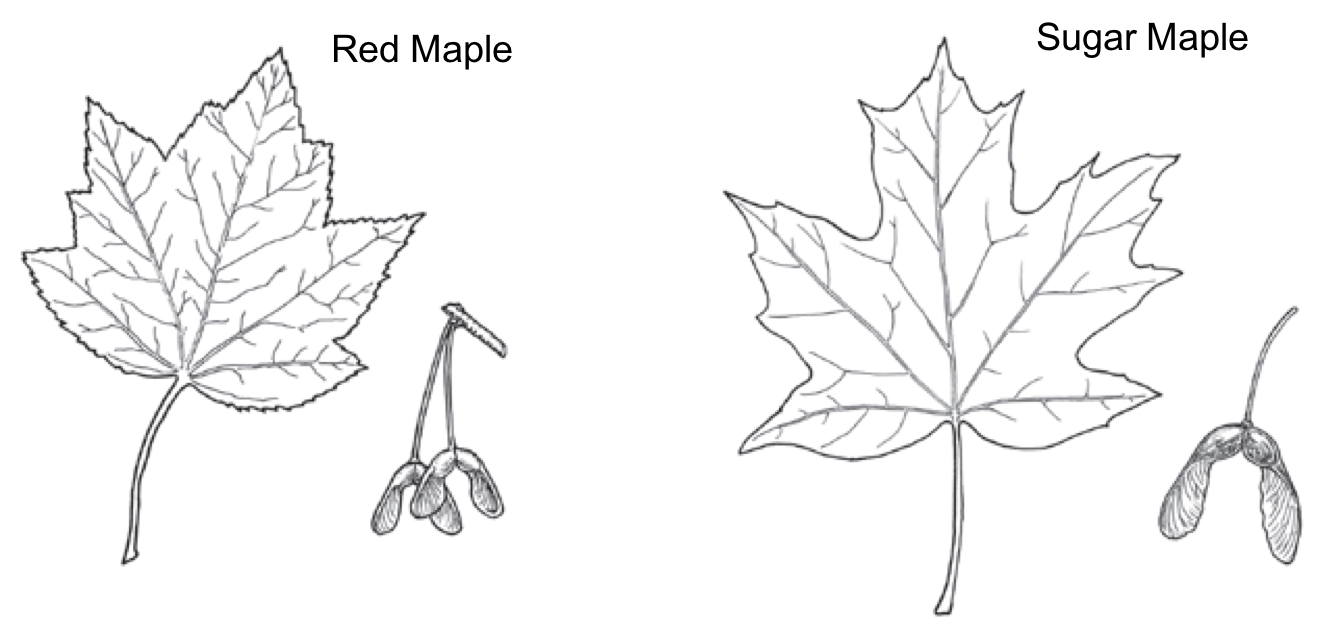

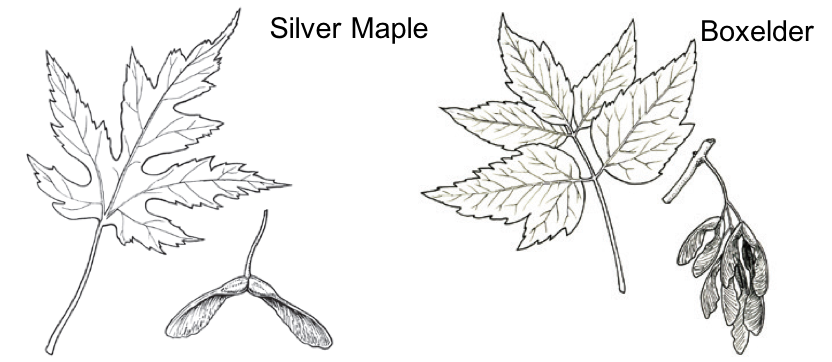

1. Genus Acer – Maple. Maples have tiny, inconspicuous flowers in the spring. The fruit/seed are winged samara, usually in joined pairs and designed to be carried by the wind. The samaras are colloquially called “helicopters.” The time when the samaras are produced varies according to the species. For example, red maples produce samara before the leaves come out in the spring. Other species produce samara after the leaves appear later in the season. Leaves are opposite and most, but not all, are palmately lobed. Leaves have 3 to 5 lobes with coarsely toothed edges. The characteristics of the wood vary according to species. For example, red maples produce cream colored wood that is soft and rather weak and is used for furniture and paper pulp. Sugar maples produce pale brown or pink wood that is heavy, strong, and close grained and is used for flooring as well as furniture. Wood from silver maples is soft, brittle, and weak and is used for boxes, furniture, and fuel. There are 15 species of maples in eastern North America of which 9 are native.

Red Maple (Acer rubrum L.) is one of the most common and abundant trees in eastern North America forests. The U.S. Forestry service has noted dramatic increases in the number of red maples in eastern North American forests since the 1970s, with the red maple replacing other species (generally not considered a good thing). These increases have been achieved primarily for two reasons. First, the species grows in a wide variety of conditions from swamps and wetlands to dry uplands, tolerating the widest variety of soil conditions of any North American forest species. Second, the tree is not tolerant of fire and the suppression of fire has enabled the proliferation of the species in the forests.[22] The tree is considered an understory tree in forests but can grow up to 90 feet tall.The species gets its name, red maple, from the red flowers, samara, leaf stems, and fall color. Flowers appear in the spring before leaves appear and are red, attractive but very small. The red flowers are followed by reddish, paired samara which give the impression of flowers from a distance. Individual samaras are relatively short (½ to ¾ inches) compared to the samaras of other maple species. Leaves appear after the samaras. Leaves have 3 to 5 lobes and are coarsely, but finely, toothed. The leaf stem is often red. In the fall, the leaves turn brilliant scarlet, orange or yellow.

Silver Maple (Acer saccharinim L.) is a medium to tall tree that was popular as a yard tree in the mid-20th century. Flowers are greenish to reddish in dense clusters and appear in the spring long before the leaves. The samaras are longer (1.5 to 2.5 inches) than those of the red and sugar maples. Leaves have 5 main lobes with deep sinuses. Lobe edges are coarsely toothed. The species gets its name from the silver underside of the leaves. The leaves turn yellow in the fall.

Boxelder (Acer negundo L.) is a medium height tree that is frequently multi-stemmed. Unlike the previously discussed maples, male and female flowers of the boxelder occur on separate trees. Flowers are yellow-green in drooping clusters, appearing in late spring before or with new leaves. The samaras also appear in drooping clusters. The most distinguishing characteristic is the pinnately compound leaves that commonly have 3 leaflets, but sometimes 5 and rarely 7 to 9 leaflets. This is a distinct difference from the other maples that have simple leaves. The form of the boxelder leaf reminds one of a simple maple leaf that has been cut apart to form leaflets. The leaflets are coarsely toothed. The 3-leaflet form resembles poison ivy. In the fall, the leaves turn yellow.Other maples with which Tree Stewards may want to be familiar include:

- Striped Maple

- Black Maple

- Japanese Maple

- Norway Maple (introduced from Europe, considered invasive in the Northeast)

2. Genus Aesculus – Buckeyes and Horse Chestnuts. Buckeyes and horse chestnuts generally are of medium height. They can be recognized by their palmately compound leaves with 5 to 11 leaflets occurring opposite each other on branches. The edge of the leaflets is toothed. Flowers are elongated, often cone-shaped terminal clusters that appear after new leaves. The fruit is produced in pear shaped or rounded green or brown leathery capsules that usually have 1 to 3 large seeds and occasionally 4 to 6. At maturity, the seed capsule commonly splits into 3 parts.

Yellow Buckeye (Aesculus flava Ait.) has leaves that are 10 to 15 inches long with 5 to 7 oval leaflets, each 3 to 7 inches long. The flowers are pale yellow-orange in large, showy upright 4 to 8 inch clusters. The flower petals have two different lengths. The fruit is 2 to 3 inches long with 1 to 3 brown nuts with a spot on one side. The nuts are poisonous to eat. The wood is light, soft, and close-grained and is sometimes used for pulpwood and woodenware.

3. Genus Koelreuteria – Goldenrain Tree. Genus is native to Asia, but all three species have been introduced into the United States. Only one is significant as a landscape tree in Virginia.

Goldenrain Tree (Koelreuteria Paniculata Laxm) is a short tree with a spread equal to its height. Leaves are pinnately (or partially bi-pinnately) compound, 8 to 14 inches long and with 9 to 15 leaflets. The compound leaves are alternate but the leaflets are opposite and have irregular serrations or lobes. The tree has showy, large bright yellow flowers that appear on 10-15-inch-long panicles (a loosely branched flower cluster in a somewhat pyramidal form).

Additional Trees Worthy of Note

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.) is sometimes called a living fossil. The tree essentially has not changed for more than 200 million years. In the distant past, there were other ginkgo-like plants but these plants no longer exist. The ginkgo is now the only plant in its genus (Ginkgo L.), family (Ginkgoaceae), order (Ginkgoale), class (Ginkgoopsida), and division (Ginkgophyta). One has to go all the way back to the superdivision (Spermatophyta – the point at which seed producing plants and spore producing plants separate) to find a taxonomical category where there are other plants in addition to the ginkgo.

At the division level, flowering plants (angiosperms) split off into the Magnoliophyta Division. All four divisions of non-flowering plants are considered gymnosperms. However, the ginkgo does not adhere to several of the criteria that apply to other gymnosperms. The form of the seeds, growth form, and foliage differ substantially from other gymnosperms. Stubby, short pegs protrude from the twigs. From these pegs, clusters of leaves grow.

The leaves appear to have more in common with angiosperm trees than the needles and scale-like leaves of conifers. The ginkgo does not have flowers. Its leaves are shaped like fans with a radiating pattern of veins. No other tree has a similar shaped leaf or similar vein pattern. The seed of the ginkgo is produced on female plants. While the seed is considered naked, it has a fleshy covering, unlike the hard seeds of other gymnosperms. This covering has a foul odor, like rotten meat, when it drops to the ground. The seeds themselves are edible and are a delicacy in many parts of Asia.

The ginkgo can be a tall tree and is resistant to pollution. Males are frequently used as street trees. The leaves turn bright yellow in the fall. Most of the leaves fall from the tree in a short span of time rather than over several days or weeks.

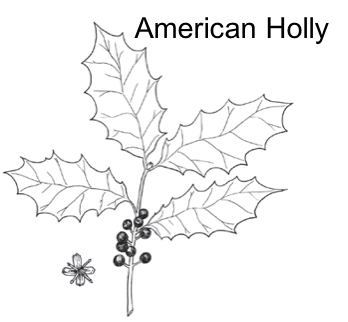

American Holly (Ilex opaca Ait.) is a medium height tree with a diameter of 1 to 2 feet. It is a very common understory tree in Virginia forests. The evergreen leaves are alternate, simple, leathery, glossy green and stiff. They are elliptical, 2 to 4 inches long, with 1 to 7 large, sharp, spine-tipped teeth. The bark is light gray and smooth throughout the life of the tree. Male and female flowers are on separate trees. Female trees produce ¼ inch bright red berry-like fruit that matures in October and persists on the tree over winter.

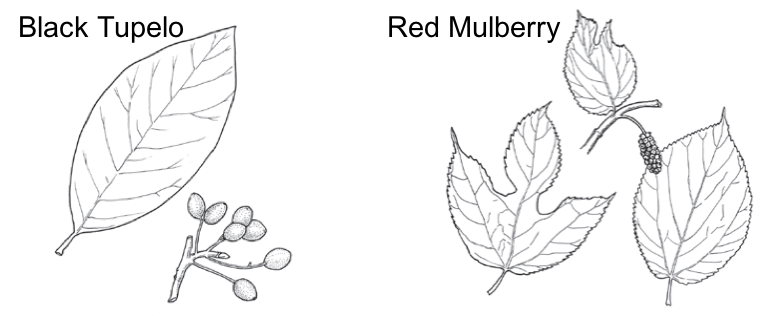

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra L.) is of medium height with a 1 to 2 feet trunk and prefers a rich, moist soil. Leaves are alternate, simple, 3 to 5 inches long, with toothed edges. Leaves can have multiple shapes: oval, one lobe (mitten shaped), or 3 or more lobes. The leaves of young trees tend to have more lobes. Mature trees tend to have mostly leaves with no lobes. The leaves have stiff hairs on the top that make them rough to the touch; however, the underside can feel downy. Flowers are pale green, tiny, and clusters on 1 to 2 inch catkins (male) or 1 inch catkin (female). Male and female flowers may be on the same or separate trees and appear with the leaves in the spring. The mulberry fruit looks like a small blackberry that starts out red and then ripens to deep purple in mid-summer. The fruit is sweet, juicy, and edible. They also make a mess where they fall under the tree. The wood is light, soft, and not strong but quite durable. Examples of uses are fencing and barrels.The white mulberry (Moras alba) is the main food source for silkworm caterpillars. In the early colonial period, white mulberries were brought to the United States in the hope of establishing silk production. This was unsuccessful but white mulberry became naturalized throughout the southern states.

Big Tree Program

American Forests, a non-profit conservation organization, sponsors the National Big Tree Program and maintains the Champion Trees National Register. The register contains information on American’s biggest trees, the largest recorded living specimens of each tree type measured by height, trunk circumference, and crown spread. Trees species must be either native or naturalized in the continental United States to be eligible. The continental United States includes the 48 lower states and Alaska but not Hawaii. The National Register of Big Trees has been maintained by American Forests since 1940 and currently contains over 700 Champion Trees.

The following formula is used to calculate a point score for each tree:

Trunk Circumference (in inches) + Height (in feet) + 1/4 Average Crown Spread (in feet) = Total Points

The current list of National Champion Trees is available online at:

Several states, counties, and cities maintain their own list of local Champion Trees. Virginia has consistently ranked in the top five states for national champion trees. The Virginia Big Tree Program is a educational program of the VCE, coordinated by the Department of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation at Virginia Tech. The Virginia Big Tree Register maintains information on the five largest specimens of over 300 native and naturalized tree species. The Virginia website provides photographs of the trees, their location, the names of the individuals who nominated them, and in some cases, the name of landowner. The Virginia website is:

http://bigtree.cnre.vt.edu/search.cfm

How to Measure Trees

Trees are commonly measured by three parameters: height, girth, and crown spread.

Height is the vertical distance from the base of the tree to the highest sprig at the top of the tree. The base point is the point at which the tree germinated. If the tree is on a slope, the base point is the ground level halfway between the upper and lower sides of the tree.

Girth is a measurement of the circumference of the tree measured at 4.5 feet above ground level. If there are significant branches below this height, then the girth should be measured at the narrowest point below the lowest branch and that height noted. If there is a burl or protuberance at the measurement height, then the girth should be measured immediately above the protuberance or at the narrowest point of the trunk below the protuberance and that height noted. If there are multiple trunks, measure with a tape measure around all trunks at the 4 ½ feet height.

Crown spread measures the footprint of the crown of the tree expressed as a diameter. The simplest approach is to take measurement along the longest axis of the crown from one edge to the opposite edge. A second measurement is take perpendicular to the first lie through the central mass of the crown. The two measurements are then averaged to reach a number for crown spread.

More in-depth discussions of taking tree measurements can be found in the following publications: American Forests Champion Trees Measuring Guidelines Handbook and The Tree Measuring Guidelines of the Eastern Native Tree Society.[23][24]

Review Questions

- There is one standard recognized dichotomous key to identify trees. (T/F)

- Why is the family level of taxonomy classification important in gardening.

- A group of living things can interbreed if they are in the same ____________ (level of taxonomy).

- What is the difference been gymnosperms and angiosperms?

- What is the difference between monocots and dicots?

- The division of familiar trees that are gymnosperms are called _________.

- What are the differences and similarities between the Cypress and Pine Families?

- The most obvious common characteristic of the Fabaceae Family is ___________.

- The _______________ is well-known tardily deciduous tree with smooth silver bark.

- What tree genus has with a wide diversity of leaf shapes, can be either evergreen or deciduous, and a large number of species in Virginia?

- What once dominant tree species has been devastated by a blight and now is only seen as sprouts from stumps?

- Pinnately compound leaves are characteristic of what tree family?

- What are the two most ancient tree families, one dating back 100 million years and the other going back 200 million years? Contrast the primary characteristics of these two families.

- Many of our most common fruits come from plants in the _____________ family.

- Aspirin is made from compounds found in trees from the ______________ family.

- Maples were traditionally considered a tree family but now are a genus within the ___________ family.

- What tree is the only species remaining in its family?

- What two tree species both produce 1 inch seed balls? Contrast the balls.

- The largest trees of their species are documented in what registry?

- What are the three dimensions measured for trees?

- Basic Biology. (May 21, 2015). Basal Angiosperms. https://basicbiology.net/plants/angiosperms/basal-angiosperms ↵

- Virginia Department of Forestry (2016). Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification Guide. Virginia Department of Forestry Publication P00026. www.dof.virginia.gov ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (n.d.). PLANTS Database. USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service. https://plants.usda.gov/java/ ↵

- Ware, S. (January 22, 2020). Taxonomy of Trees [Powerpoint]. Peninsula Tree Steward Class. ↵

- Virginia Botanical Association. (2017). Digital Atlas of Virginia Flora. http://www.vaplantatlas.org ↵

- Watts, M.T. (1998). A Manual for the Identification of Trees by Their Leaves. Nature Study Guide Publications. ↵

- Basic Biology. (May 21, 2015). Basal Angiosperms. https://basicbiology.net/plants/angiosperms/basal-angiosperms ↵

- Virginia Department of Forestry. (2016). Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification Guide. Virginia Department of Forestry Publication P00026. www.dof.virginia.gov ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (n.d.). PLANTS Database. USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service. https://plants.usda.gov/java/ ↵

- Nelson, G., Earle, C., Spellenberg, R. (2014). Trees of Eastern North America, Princeton Field Guides. Princeton University Press. ↵

- Virginia Botanical Association. (2017). Digital Atlas of Virginia Flora. http://www.vaplantatlas.org ↵

- Nelson, G., Earle, C., Spellenberg, R. (2014). Trees of Eastern North America, Princeton Field Guides. Princeton University Press. ↵

- American Forest. (n.d.). Champion Trees National Register. http://www.americanforests.org/explore-forests/americas-biggest-trees/champion-trees-national-register/ ↵

- America’s Longleaf Restoration Initiative (ALRI). (n.d.). American’s Longleaf. http://www.americaslongleaf.org/home/ ↵

- America’s Longleaf Restoration Initiative (ALRI). (n.d.). American’s Longleaf. http://www.americaslongleaf.org/home/ ↵

- American Conifer Society (2020, September 4). 10 Types of Cedar Everyone Should Know. https://conifersociety.org/conifers/articles/types-of-cedar-trees/ ↵

- Watts, M.T. (1998). A Manual for the Identification of Trees by Their Leaves. Nature Study Guide Publications ↵

- . Elpel, T.J. (2013). Botany in a Day: The Patterns Method of Plant Identification (6th ed.). Hops Press, LLC. ↵

- Nelson, G., Earle, C., Spellenberg, R. (2014). Trees of Eastern North America, Princeton Field Guides. Princeton University Press ↵

- Elpel, T.J. (2013). Botany in a Day: The Patterns Method of Plant Identification (6th ed.). Hops Press, LLC ↵

- Nelson, G., Earle, C., Spellenberg, R. (2014). Trees of Eastern North America, Princeton Field Guides. Princeton University Press. ↵

- Alderman, D.R. Jr., Bumgardener, M.S., Baumgras, J.E. (September 1, 2005). An Assessment of Red Maple Resource in the Northeastern United States. Northern Journal of Applied Forestry. 22(3). https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/7698 ↵

- Leverett, R., Bertolette, D. (2015). American Forests Champion Trees Measuring Guidelines Handbook. https://www.americanforests.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/AF-Tree-Measuring-Guidelines_LR.pdf ↵

- Blozan, W. (October 1, 2004). The Tree Measuring Guidelines of the Eastern Native Tree Society. http://www.nativetreesociety.org/measure/Tree_Measuring_Guidelines-revised1.pdf ↵