Chapter 3: The Benefits (and Disadvantages) of Trees

"A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees” -William Blake

Chapter Contents:

Introduction

This chapter will discuss the benefits and disadvantages of trees. Trees are a valuable resource and a benefit to the community and world – for construction of homes, as an oxygen source, as a source of recreation, and as a partner in the symbiotic relationships between other plants and animals. However, there are also disadvantages to a poorly placed tree or mismanaged forest.

Albert Einstein “it would be possible to describe everything scientifically, but it would make no sense….as if you described a Beethoven symphony as a variation of wave pressure.”

Trees have not only measurable, quantifiable benefits and disadvantages, but also those not adequately addressed through scientific means. Trees have been the source of inspiration for poets, musicians, and artists. How can you measure the worth of a childhood tree climbed repeatedly, or the beautiful beech with lover’s initials, or the tree planted in memory of a loved one?

This chapter will generally focus on the urban tree - a tree planted for a specific purpose in a specific location as part of a city or private home landscape - and the urban homeowner. One cannot ignore the importance of the vast amounts of forest and undeveloped land globally to the urban homeowner, areas such as the Amazon rainforest. The trees from the Amazon Basin cover 2.7 million square miles of South America; is estimated to have 16,000 tree species and 390 billion individual trees[1]. More than 20 percent of the world’s total oxygen is created by this rain forest, and it is being deforested at an alarming rate.[2].

We also cannot ignore the impact of the solitary tree, grove of trees, a forest, or a planned city park in the US. Throughout our short American history, the planting of trees has been an activity for both recreation and economic value. Andrea Wulf proposed in Founding Gardeners that Washington, Jefferson, and Madison considered themselves farmers first and politicians second.[3] Each planted numerous trees, both native and exotic, on their plantations for economic and aesthetic reasons, scouring the nearby forests for suitable trees to transplant or bringing back seedlings from their foreign travels.

In 2012, according to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) of the total 2,261 million acres in the US, 819 million acres were forests or woodlands, or 36 percent. Of the total forest land, 56 percent are privately owned. Only nineteen percent can be found in National Forests.[4] “Forests in the United States continue to sequester more carbon than they emit each year, and combined with urban forests, and harvested wood products, offset nearly 15 percent … of total greenhouse gas emissions in 2012.”[5]

With much of US forests privately owned, it is important to understand the benefits and costs to the individual owner. Forty percent of the nation’s timberland is in the South. “And the South is often referred to as the “woodbasket" of the United States because of its extensive timber supply.”[6] In addition, the proportion of land in the US classified as “urban” has increased from 2.5 percent in 1990 to 3.6 percent in 2010.[7] Along with the increasing urbanization of the US, it has also been reported that tree cover in urban areas is on the decline.[8],[9]

As the proportion of land classified as urban increases, and the amount of tree cover decreases in cities, it is important to consider and emphasize the benefits (and disadvantages) of trees. According to Kane and Kirwan, the proportion of the US population located in urban areas has grown from 28 to 80 percent from 1910 to 2000.[10]

Trees can be assets or liabilities, depending on the choices made. Careful consideration should be made, and education provided, in their planning, location, planting and maintenance. Unlike the annual flower garden, trees may outlast the planter. In addition, the private homeowner can control their own trees; but a neighbor with a poorly placed tree, an undeveloped forest rezoned for residential development, or the importance of timber in the economy are all considerations to be addressed.

Learning Objectives

- Understand that a tree or trees have both benefits and disadvantages.

- Understand the economic, social/aesthetic, community and environmental issues of trees.

- Understand the local, regional, state, federal and global roles of trees on the urban homeowner.

REVIEW: VCE Master Gardener Handbook 2015 (9/18 update)

- Chapter 16: Woody Landscape Plants

- Chapter 19: Water Quality and Conservation

- Chapter 20: Habitat Gardening for Wildlife.

The Big Picture

What are the benefits of urban trees? According to Kane and Kirwan they can be classified into three categories: ecological (including reduction of air pollution, storm water control, carbon storage, water quality and reduced energy consumption); social benefits (including job satisfaction, hospital patient recovery time, improved child development); and aesthetic value (increased property values).[11]

Relf and Close state that landscaping improves and sustains the quality of life.[12] It enhances the environment (protecting water quality, reducing soil erosion, improving air, lowering summer temperatures, conserves naturals resources, screens busy streets); promotes economic development (increasing property values, increases community appeal, reduces crime, increase tourism revenues, increases job satisfaction, increases worker productivity, and renews business districts); and improves human health (gardening is good exercise, horticulture is therapeutic and landscapes heal).

According to the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) trees have social, communal, environmental and economic benefits.[13] However, they also require an investment.

We must also consider other benefits of trees – those less associated with the quantitative values. If not for the apple tree, would Newton have pondered gravity? Where would the cardinal lay its nest, if not for trees? Where would birds shelter from the snow storm? What of the myriad of insects both within and under the tree? Trees protect what lies underneath through interception of rain, protect soil from erosion and shelter the more fragile understory shrubs and plants.[14] There is a deep symbiotic relationship between trees and the flora and fauna dependent on it.[15] The nuts of the acorn, the cone of the pine, and the fruit of the paw paw all provide sustenance, without which wildlife will struggle to survive.

There are disadvantages to be considered. The deer not only eat the acorns, but also the homeowner’s prized azaleas. The sweet gum provides shade but also gumballs, and the pawpaw produces quantities of desirable edible fruit that on a sweltering summer day can be pungent. And almost any urban tree requires care not only in its selection and planting but in continuing maintenance of the tree and its site. Otherwise, the tree may interfere with important infrastructure and even become a hazard.

This chapter is organized by the size of the community where trees are found. The benefits/ disadvantages are discussed within the categories proposed by the ISA – economic, social/aesthetic, community and environmental.

The Private Home Owner

The economic benefit of trees is undeniable for the home owner. According to Relf and Close, an attractive landscape with trees increases the value of a home by 7.5 percent.[16] Appropriately placed shade trees can lower summer temperatures of the home – thereby conserving energy. Homes sheltered by appropriately placed evergreen screens can reduce heat loss in the winter by blocking winds, thereby conserving energy. According to Litvak and Pitaki landscapes that combine both trees and lawns consume less water than landscapes with only lawns.[17]

We can calculate the benefit of a tree to an amazing degree. Try calculating the benefits of a tree in your area using the iTree calculator here: https://planting.itreetools.org/ Benefits are estimated based on USDA Forest Service research and are meant for guidance only).

Trees can also effectively beautify or screen unsightly areas, an aesthetic benefit. According to Appleton, et al.[18] trees can be used to define a private space, or to hide utility boxes. They can control noise from a busy street, and filter light. For the nature lover, a tree encourages wildlife habitats. Trees are said to have a calming effect.[19] They are planted as memorials. Many outdoor recreational activities such as hiking and “just sitting on the back porch are more enjoyable in and around trees.”[20] Fruit and nut trees provide edible produce.

MyTree Benefits: Serving size: 1 tree

This is an analysis of a loblolly pine in the Tidewater area of Virginia. (http://www.davey.com/calculator) Benefits are estimated based on USDA Forest Service research and are meant for guidance only: www.itreetools.org

*Positive energy values indicate savings or reduced emissions. Negative energy values indicate increased usage or emissions.

**is not greater than 10 microns

| Item | Savings |

|---|---|

| Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Sequestered | $2.04 |

| CO2 absorbed/stored each year | 203.68 lbs |

| Storm Water | $70.37 |

| Rainfall intercepted each year | 7108 gal. |

| Air Pollution removed each year | $3.10 |

| Ozone | 11.44 oz |

| Nitrogen dioxide | 3.88 oz |

| Sulfur dioxide | 2.28 oz |

| Large particulate matter ** | 8.33 oz |

| Energy Usage each year* | $19.20 |

| Electricity savings (A/C) | 27.33 kWh |

| Fuel savings (NG,Oil) | 11.97 therms |

| Avoided Emissions | |

| Carbon dioxide | 238.02 lbs |

| Nitrogen dioxide | 0.71 oz |

| Sulfur dioxide | 10.73 oz |

| Large particulate matter ** | 0.27 oz |

Research conducted by Townsend, et al, indicated that not only did street trees provide significant reduction of stress in a community, but private trees on community streets (those trees owned by a private home owner) augmented that reduction.[21] They stated if community/street tree planting is not an option then encouraging private tree planting and maintenance would have a community benefit.

The environmental benefit of tree planting by the private home owner is significant. Trees protect and improve water quality, reducing nitrate leaching and surface water runoff.[22] It reduces soil erosion, keeping sediment out of streams and rivers and on the property. It improves air quality – one tree can remove 26 pounds of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere yearly. Trees intercept water – falling rain is slowed by the leaves – allowing for better absorption and less run off. Leaves also remove dust and other particulates from the air.[23] Most importantly, they store the carbon removed (sequestration), which reduces the green-house effect that is related to global climate change.[24]

There are also disadvantages to trees for the homeowner. Trees can be expensive to purchase and maintain. Ko, et.al., found that in their study of a tree give-away program in Sacramento, California, that only 23% of the trees planted had maintenance that followed guidelines.[25] Trees also are a longer-term investment – often the owner/planter will not be alive or live in the area to see the full maturation of a tree. To some, planting a tree is a blind belief in the future.

Trees also can become hazards to the home in the wake of hurricanes or storms. Leaves need to be raked. Sap drips. Sidewalks, driveways, and brick walls crack if too close to tree roots. Birds leave droppings. Trees can shade a lawn to the point where grass won’t grow. Roots protrude from the soil. Trees encourage wildlife. Gumballs and pinecones are hazards to bare feet. However, generally, the economic, aesthetic, community and environmental benefits outweigh the disadvantages for the private home owner.

Deep in the Quiet Wood[26]

by James Weldon Johnson

Are you bowed down in the heart?

Do you but hear the clashing discords and the din of life?

Then come away, come to the peaceful wood,

Here bathe your soul in silence.

[...]

The Community and Neighborhood or City

Many of the same benefits to a private home owner apply also to communities, cities or regions. Like a Gestalt, the urban forest is more than the sum of the individual trees in it. Cities and communities spend large sums of limited fiscal resources to plan green space on highway medians, to protect and maintain city parks, and to set environmental regulations such as the number of trees to be planted in parking lots.

“The total area covered by urban parkland in the United States exceeds one and a half million acres, with parks ranging in size from the jewel-like 1.7-acre Post Office Square in Boston to the gargantuan 490,125-acre Chugach State Park in Anchorage. And their usage dwarfs that of the national parks—the most popular major parks, such as Lincoln Park in Chicago receive upwards of 20 million users each year, and New York's Central Park gets about 35 million visits annually—more than seven times as many to the Grand Canyon.”[27]

In Virginia, according to the Trust for Public Lands, the five largest amounts of acreage in municipal parks can be found in: Arlington (1,784 acres), Chesapeake (56,869 acres), Norfolk (607 acres), Richmond (2,027 acres), and Virginia Beach (24,936 acres).[28] However, Newport News Park, not mentioned in the report, covers 8,065 acres.

For example, according to the Virginia Beach Parks and Recreation website, Virginia Beach has 293 city parks covering 7000 acres; the remainder of the acreage is denoted as natural areas. According to the Virginia Beach City Parks and Natural Areas website: “A natural area is a municipal preservation area whose primary purpose is to preserve the indigenous vegetation and wildlife in order to serve as green infrastructure and as a scenic environment for Virginia Beach residents to enjoy. Natural areas include areas for protection and management of the natural/cultural environment with recreation use as a secondary objective. Recreational use might include passive recreation activities such as hiking, birding, and environmental education, but may also include public waterway access improvements, public fishing opportunities, and trail connections.”[29]

Cities across the US have set aside, and continue to set aside, areas for city parks and natural areas. The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation reports on their website that “Outdoor recreation supports a high quality of life, attracts tourists, and sustains the well-being of Virginia’s residents and guests. According to the Outdoor Industry Association, outdoor recreation in Virginia generates $21.9 billion in consumer spending annually and directly provides 197,000 jobs.”[30]

Not only do urban/city natural areas provide economic benefits, in terms of tourism, and improved quality of life to residents, these natural areas reduce storm water runoff, improve area air and water quality. Desirable neighborhoods have access to natural areas, streets are lined with trees, and home owners increase their property value with trees and other landscaping. Increased property values then lead to increased revenue for the local cites.

Highways and streets are improved with green medians including trees and shrubs. Research has shown that trees have a traffic calming effect. According to Marritz, street trees play a role in speed control, with street lined trees reducing traffic speed by 8 mph. They also noted that a site in Texas that improved landscape decreased crash rates by 46%; and that a healthy canopy of trees can help reduce stress and road rage.[31]

Dunn (writing for the organization Friends of Frink Park) notes that cars drive more slowly on streets with trees; street trees cut traffic noise; residents walk more on streets with trees; trees improve air quality, and increase property value.[32]

Neighborhood trees and parks have economic, aesthetic, and environmental benefits. They also have social/community benefits. Beyond the reduction of road rage, and general noise reduction, trees have other public health benefits.

Trails encourage walking, and the medical benefit of walking cannot be argued. Trees have been found to improve attention, decrease asthma and obesity, improve physical and mental health, and have been related to reduced hospital stays. A green canopy provides shade, cooler temperatures, and protection from the sun's UV rays on hot days.

Just as for the private home owner, street and parking lot trees provide shade for cars and residents; they absorb storm water, improve air quality, and store carbon. Parks without trees cannot sustain significant wildlife, at least in Virginia’s ecology.

Trees and parks do have their disadvantages. Trees can be difficult and costly to maintain, especially after storms. Hurricane and tornado damage of trees can block roads needed for emergency access. They often are the cause of electrical outages – branches and trees taking down power lines. Tree leaves can block storm drains, and are a nuisance for the home and business owner in the fall. Improperly placed berry producing trees can damage homes, cars and businesses. Trees provide shelter for birds and wildlife, which can then leave droppings. They are also a significant source of pollen in the spring and summer for allergy sufferers. However, the pollen is a boon to the car wash industry and allergy medicine producers, but leaves the individual and region under a blanket of misery.

Parks may also have a negative economic impact. They often displace land that could be developed for businesses or homes which would result in increased real estate revenue. An acre of non-taxable trees will never equal the potential for tax revenue income of a business or home.

In summary, just as with the private homeowner, urban trees planted by municipalities and cites have advantages: improved air and water quality, increased tourism, positive health effects, options for recreation, and increased property values. However, poorly placed trees or improper selections can lead to increased maintenance and storm cleanup, power disruptions, blind spots on roads, and clogged storm water drains. Also, in a short-sighted view, every acre without development can have impact on the local or regional tax revenues.

State and National Forests

In Virginia, the Department of Conservation and Recreation is responsible for the 37 state parks. These parks provide numerous recreational opportunities and over 626 miles of hiking. These parks encompass 72,793 acres. The first parks were established in 1933 with the latest with the latest addition in 2021 – the Machicomoco State Park.[33] The economic value of state parks was $222.8 million dollars in 2015 (half from visitor fees.) According to the Virginia Association for Parks, the state parks attract $171 million dollars in “new money” at the cost of $18 million dollars in general funds.[34] Property values around state parks increase by 20 percent. They create over 2500 jobs. State parks host 8.9 million visitors, and almost half of every household in Virginia visit a state park every year.

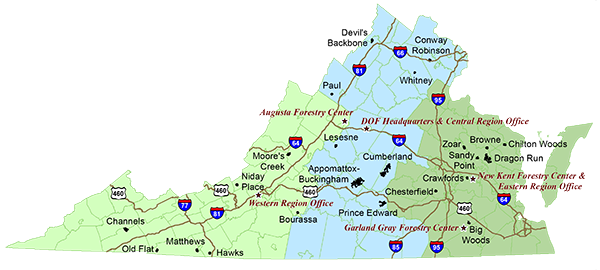

The Virginia Department of Forestry manages 24 areas for a total of 68,626 acres. The goals of DOF are: manage the forest land for steady supply of timber; provide recreational opportunities; maintain aesthetics; maintain wildlife habitats; create natural reserves; and preserve water quality.[35]

According to the Virginia Department of Forestry, Virginia has 15.72 million acres of forestland, and 62% of Virginia is considered forested. Urbanization and development are the biggest factors in loss of forests. It is also noteworthy that private individuals own more than two-thirds of Virginia’s timberland.[36] An interactive version of the map below may be found at: https://dof.virginia.gov/education-and-recreation/state-forests/virginia-state-forests/

The forest resource contributes $17 billion annually to Virginia’s economy; supports one of the largest manufacturing industries in the state (lumber); $3 billion dollars in recreational opportunities, and generates 103,000 jobs. Besides their obvious economic benefit, forests provide large watersheds, long term carbon sequestration, and social benefits (scenic beauty, wildlife habitat, and desirable housing locations).[37]

National forests in Virginia fall under the US Forest Service under the US Department of Agriculture. The two managed forests are the George Washington and Jefferson located in the western portion of the state along the Appalachian Mountains.[38]

These two forests contain 1.8 million acres, making up one of the largest blocks of public land on the East Coast. It stretches through Virginia, Kentucky and West Virginia. Virginia’s acreage is 1.6 million acres. These forests are home to: 40 species of trees, 2000 species of shrubs and plants, 78 species of amphibians and reptiles, 200 species of birds, 60 species of mammals, 100 species of freshwater fishes and 52 federally listed Threatened or Endangered Species.

Of the 1.8 million acres, almost 40% (689,000 acres) are actively managed to produce timber and wood products. These forests are in 8 watersheds: Potomac, James, Roanoke, New, Big Sandy, Holston, Cumberland and Clinch River. Average surface water discharge to these watersheds is 2.2 million acre feet. There are 82 reservoirs in these forests, 16 of which are used for municipal water supply.[39]

Though this chapter’s focus is on the urban tree, it would be negligent not to discuss the impact of state and national forests on the urban dweller. Forests provide one of the largest industries in Virginia. The national and state forests filter water for those not only local, but through the numerous watersheds effects, thereby effecting the water quality of our rivers throughout Virginia. The reservoirs in state and national forests provide our drinking water. Air quality is improved, and carbon is sequestered.

However, the need for land for development must be noted. Large tracts of forested land are attractive to developers. Cities need to expand. Urban sprawl continues outward. The urban dweller is thus influencing and being impacted by their own trees, the neighborhood and street trees, and the trees from far away on rural private, state and national forests.

The Urban Tree and Climate Change

This chapter will not get involved in the discussion on whether climate change is caused by human factors. However, it is undeniable that climate change is happening. US Hardiness zones have been recently revised with warmer zones reaching further north than previously. Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane are increasing in the upper atmosphere. Trees are one means of carbon sequestration. More trees, more carbon sequestered. Trees are much more efficient than smaller plants at sequestration because of their larger size and root structures. According to Earth Talk, trees are means of climate change mitigation.[40]

Unlike state and national agencies responsible for protection and preservation of trees, there is no one international/global agency monitoring and researching the effects of deforestation on climate and humans. The United Nations has created the Billion Tree Campaign “to encourage people, communities, organizations, business and industry, civil society and governments to collectively plant at least one billion trees worldwide each year.” The Union of Concerned Scientists warn of the perils of worldwide deforestation and global warming.[41]

Trees[42]

by Joyce Kilmer

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree [...]

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

As technology develops, research on global forests and deforestation has been ongoing through remote sensing via land sat data, the US Geological Survey, NASA, NOAA and the International Union of Forest research Organization.

As you sit and read this manual, note the extensive amount of tree products around you – the chair you sit in; the coffee or tea that you are drinking; the table on which your cup rests; the apple you eat; or the fireplace that warms you on a cold night. The urban homeowner is surrounded by trees, living and dead.

However, choosing an appropriate tree and planting it correctly is not the simple answer to a complex issue. As the research of Ko, et al, Sacramento study showed, giving away trees for planting is not the answer.[45] Only 23 percent followed recommended guidelines for maintenance, leading to significant mortality. City tree life spans are between 10 and 30 years, compared to a rural tree’s average life span of 150 years.[46]

According to Roman, even though there has been a major focus on city tree planting, the amount of overall canopy is decreasing. The research reports that life span of the typical street trees is 19 to 28 years with an annual mortality rate of 4-5%.[47] In other words, at a mortality rate of 5 percent, in 20 years all the street trees planted in one year (with an average 19 year life span) would have died. If these numbers are true, then we are not catching up with the loss of trees, but merely are running a Sisyphusian task.

Correct planting and maintaining of urban trees is not the simple answer. A more coordinated and long term plan for researching the benefits of trees locally, regionally, nationally and internationally will be needed.

What can we, as individuals, do? Dave Nowak from the US Forest Service reports “Common Horse-chestnut, Black Walnut, American Sweetgum, Ponderosa Pine, Red Pine, White Pine, London Plane, Hispaniolan Pine, Douglas Fir, Scarlet Oak, Red Oak, Virginia Live Oak and Bald Cypress as examples of trees especially good at absorbing and storing CO2."[48] Plant a tree (the right tree!). Encourage others to plant a tree. Educate about the care and maintenance of a tree. As a tax paying citizen, become educated about regional, state and national issues concerning forests.

While the focus in this chapter has been the urban tree and the urban homeowner, it is evident, to quote John Donne, “No man is an island.” Trees around the globe, in our country, in our state, in our local municipalities and in our yards all have impacts on the urban individual.

Review Questions

- ISA categorizes benefits of trees into four broad types. What are they?

- This chapter discusses trees from the perspective of the urban homeowner – someone who may or may not have a tree in their yard. What benefit does a city park, state park or national forest have to an urban dweller?

- Butler, R. (2017, January 26). 10 Facts about the amazon rainforest. Mongabay. http://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/amazon-rainforest-facts.html ↵

- Taylor, L. (2012, December 21). Rain forest facts – the disappearing rainforests. Rain-tree. www.rain-tree.com/facts.htm#.We5BCGiPLIU ↵

- Wulf, A. (2012). Founding Gardeners. Vintage. ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2014, August 1). U.S. Forest Resource Facts and Historical Trends. FS-1035. ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2014, August 1). U.S. Forest Resource Facts and Historical Trends. FS-1035. ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2014, August 1). U.S. Forest Resource Facts and Historical Trends. FS-1035. ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2014, August 1). U.S. Forest Resource Facts and Historical Trends. FS-1035. ↵

- Nowak, D. J., Greenfield, E. J. (2012). Tree and impervious cover in the United States. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2012a; 107: 21-30. ↵

- Nowak, D. J., Greenfield, E. J., (2012) Tree and impervious cover change in U.S. cities. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening. 2012b; 11:21-30. ↵

- Kane, B., Kirwan, J. (2009). Value, Benefits and Costs of Urban Trees. VCE publication 420-181. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/48050 ↵

- Kane, B., Kirwan, J. (2009). Value, Benefits and Costs of Urban Trees. VCE publication 420-181. www.ext.vt.edu. ↵

- Relf, D., Close, D. (2015). The Value of Landscaping. VCE publication 426-721. www.ext.vt.edu. ↵

- International Society of Arboriculture (ISA). (2011). Benefits of trees. ISA and Trees are Good publication. www.isa-arbor.com and www.treesaregood.org. ↵

- Nisbet, T. (2005, April 1). Water Use by Trees. Forestry Commission. www.forestry.gov.uk FCIN065. ↵

- Huikari, O. (2012). The Miracle of Trees. Bloomsbury Press. ↵

- Relf, D., Close, D. (2015). The Value of Landscaping. VCE publication 426-721. www.ext.vt.edu ↵

- . Litvak, E., Pataki, D. (n.d.). Technical Fact Sheet: Water use by urban lawns and trees in Los Angeles: evaluation of current irrigation practices to develop water conservation strategies. Urban Ecology Research Lab, Department of Biology, The University of Utah. ↵

- Appleton, B., Baine, E., Harris, R., Sevebeck, K., Alleman, D., Swanson, L., Close, D. (2015). Screening. VCE publication 430-025. www.ext.vt.edu. ↵

- International Society of Arboriculture (ISA). (2011). Benefits of trees. ISA and Trees are Good publication. www.isa-arbor.com and www.treesaregood.org. ↵

- Kane, B., Kirwan, J. (2009) Value, Benefits and Costs of Urban Trees. VCE publication 420-181. www.ext.vt.edu. ↵

- Townsend, J., Ilvento, T., Barton, S. (2016) Exploring the relationship between trees and human stress in the urban environment. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 42(3) 146-159. ↵

- Relf, D., Close, D. (2015). The Value of Landscaping. VCE publication 426-721. www.ext.vt.edu. ↵

- International Society of Arboriculture (ISA). (2011). Benefits of trees. ISA and Trees are Good publication. www.isa-arbor.com and www.treesaregood.org. ↵

- Kane, B., Kirwan, J. (2009) Value, Benefits and Costs of Urban Trees. VCE publication 420-181. www.ext.vt.edu. ↵

- Ko, Y., Roman, L., McPherson, E. G., Lee, J. (2016, June 1) Does tree planting pay us back? Lessons from Sacramento, CA. Arborist News. 25(3); 50-54. www.isa-arbor.com ↵

- Johnson, J. W. (1917). Deep in the Quiet Wood. Fifty Years and Other Poems (pp. 47). Boston: The Cornhill Company. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t7fq9qv3r&view=1up&seq=71&q1=deep%20in%20the%20quiet ↵

- Trust for Public Land. (2011). City Park Facts Report. The Trust for Public Land. ww.tpl.org/2011-city-park-factsreport#sm.0001n5hkgg19ntfgeplswf2q79wk8 ↵

- Trust for Public Land. (2015). 2015 City Park Facts Report. The Trust for Public Land. www.tpl.org/sites/default/files/files_upload/2015-City-Park-Facts-Report.pdf) ↵

- Virginia Beach Parks and Recreation. (2017). City Parks &Natural Areas. Virginia Beach VA. https://www.vbgov.com/government/departments/parks-recreation/parks-trails/city-parks/Pages/default.aspx ↵

- Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. (2017, August 31). Outdoor Recreation: An economic engine. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. http://www.dcr.virginia.gov/recreational-planning/ ↵

- Marritz, L. (2011, October 5). Trees are a tool for safer streets. Deeproot. http://www.deeproot.com/blog/blog-entries/trees-are-a-tool-for-safer-streets ↵

- Dunn, L. (n.d.). The Benefits of Street Trees. Frink Park. www.frinkpark.org/trees.htm ↵

- Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. (n.d.). History of Virginia State Parks. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. http://www.dcr.virginia.gov/state-parks/history ↵

- Virginia Association for Parks. (n.d.). Virginia State Parks Are… Virginia Association for Parks. http://www.virginiaparks.org/ ↵

- Virginia Department of Forestry. (2016, November 1). About the State Forest System. Virginia Department of Forestry. http://dof.virginia.gov/stateforest/index.htm ↵

- Virginia Department of Forestry. (n.d.). Virginia Forest Facts. Virginia Department of Forestry. www.dof.virginia.gov/stateforest/facts/forest-facts.htm ↵

- Virginia Department of Forestry. (n.d.). Economic Benefits of the Forest Industry in Virginia. Virginia Department of Forestry. www.dof.virginia.gov/forestry/benefits/index.htm ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (n.d.). George Washington and Jefferson National Forests. USDA Forest Service. www.fs.usda.gov/gwj ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (n.d.). George Washington and Jefferson National Forests – Learning Center – About us. USDA Forest Service. www.fs.usda.gov/main/gwj/learning ↵

- Earth Talk. (2017, March 27). Which trees offset global warming best? Thoughtco. www.thoughtco.com/which-trees-offset-global-warming-1204209 ↵

- United Nations. (n.d.). Plant for the Planet: Billion Tree Campaign. United Nations. www.un.org/climatechange/blog/2014/08/plant-planet-billion-tree-campaign/ ↵

- Kilmer, J. (1915). Trees. Trees and Other Poems (pp. 19). Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t0dv20z4c&view=1up&seq=29&q1=trees ↵

- National Geographic. (2017). Deforestation. National Geopraphic. www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/global-warming/deforestation ↵

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2017, September 13). Ten things you may not know about forests. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. www.fao.org/zhc/detail-events/en/c/1033884/ ↵

- Ko, Y., Roman, L., McPherson, E.G., Lee, J. (2016, June 1) Does tree planting pay us back? Lessons from Sacramento, CA. Arborist News, 25(3); 50-54. www.isa-arbor.com ↵

- United States Forest Service. (n.d.). Forest Health Monitoring – Chapter 1 – Trees in Cities. United States Forest Service. fhm.fs.fed.us/pubs/fhncs/chapter1/trees_in_cities.htm ↵

- Roman, L. (2014). How Many Trees are Enough? Tree Death and the Urban Canopy. Scenario Journal. https://scenariojournal.com/artocle/how-many-trees-are-enough/ ↵

- Earth Talk. (2017, March 27). Which trees offset global warming best? Thoughtco. www.thoughtco.com/which-trees-offset-global-warming-1204209 ↵