6. Labor Agreements

Key Words and Concepts

- Employers

- Union organizations

- Single-employer or multi-employer parties

- Local and international unions

- Basic and specialty crafts

- Local and national agreements

- Local area-wide agreements

- Project agreements

- Industrial work agreements

- Maintenance work agreements

- Single and multi-craft agreements

- Single area system agreements

- National trade agreements

- National special purpose agreements

- Union security

- Union jurisdiction

- Hiring hall

- Grievance procedure

- Work stoppage and lockout

- Subcontracting clause

- Wage/benefit rates

- Hours worked and hours paid

- Workday and workweek

- Overtime

- Shift work

- Work rules

- Manning

- Stewards

- Me too/most favored nation provisions

The last three chapters have discussed the distinguishing features of construction industry prime contracts in general and then focused on owner-construction contractor contracts for construction services. The “red flag” clauses that determine how individual construction contracts deal with certain critical issues were examined in detail.

The focus of this chapter is on construction labor agreements, one of a series of contracts closely related to the prime construction contract. Persons aspiring to manage construction operations should be familiar with the structure of organized construction labor in the United States and with the provisions of typical labor agreements for at least three reasons. First, managers of construction operations may be employed by union contractors who consistently work under labor agreements and are generally bound by their terms. Second, even contractors who normally work on an open- or merit-shop basis may, in particular circumstances, decide to sign and be bound by a labor agreement for a particular job. Third, both union and open- or merit-shop contractors need to know under what conditions the other will be working in order to evaluate their competitive advantages or disadvantages—in other words, to get a “handle” on the competition.

Any construction superintendent or project manager knows that the cost of labor is, by far, the most volatile, difficult to control element of total construction cost. Therefore, for the sizable segment of the industry that employs union labor, the collective bargaining, or labor agreement, governing the relationships of construction employers with their workers becomes a very important agreement indeed. It is not possible to estimate accurately the probable labor element of the cost of construction without an intimate understanding of such agreements. Simply knowing the wage rates is not enough. Large cost issues depend on the intricacies of the overtime and shift work provisions, general work rules, manning requirements, and other cost-generating provisions that are often contained in labor agreements. Further, once a construction contract has been entered into with an owner, the contractor cannot effectively manage the job or control costs without a complete understanding of these often complex provisions. Each of these considerations is discussed in this chapter.

The Parties

The parties to construction labor agreements are contractor employers and union organizations. This can be represented as the beginning of a “relationship tree,” as in Figure 6-1.

Further, the employer parties in the relationship tree can be expanded to include single-employer or multi-employer parties, as shown in Figure 6-2.

A single employer consists of one contractor, whereas a multi-employer party is a group of contractors that have banded together to form an employers’ association. Examples of employer’s organizations include the various state Associated General Contractors {AGC) organizations, the National Association of Homebuilders, and the National Constructors Association.

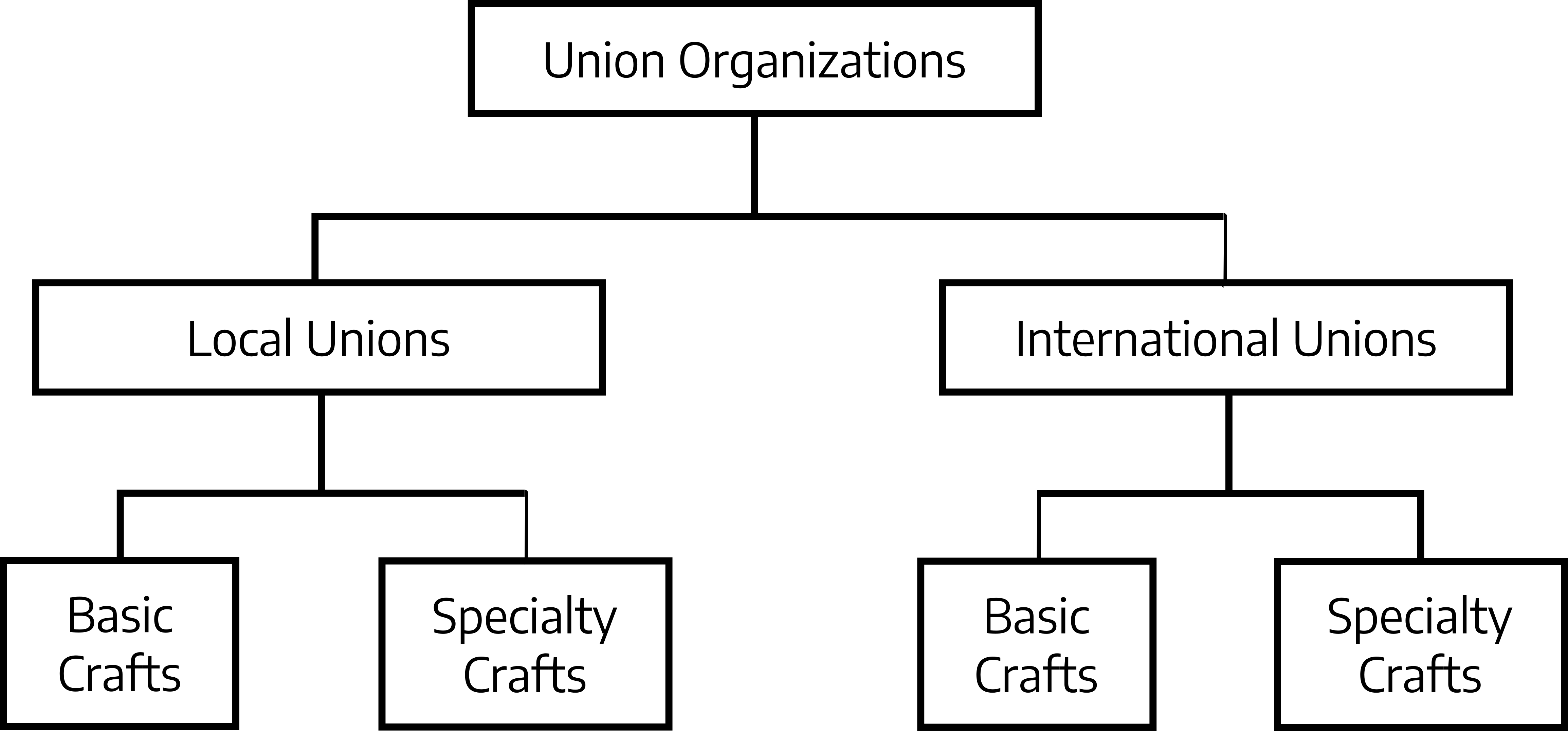

Union organizations consist of either local unions or international unions, with separate unions for the basic crafts and for the specialty crafts, as shown in a further expansion of the relationship tree in Figure 6-3.

The basic crafts consist of operating engineers, teamsters, carpenters (including piledrivers and millwrights), ironworkers, masons (cement finishers), and (although strictly speaking, not a craft) laborers. All crafts in construction other than the basic crafts are called specialty crafts, which include electricians, plumbers, sheetmetal workers, tile setters, and boilermakers, to name a few.

Common Types of Labor Agreements

Turning from the parties to the agreement itself, we see a number of features that distinguish one labor agreement from another such as the geographical limits of the agreement. Labor agreements can be local or national in geographical scope, as indicated as the beginning of a second relationship tree in Figure 6-4.

A local agreement involves just one particular local union. Usually, it also involves one craft, so it is really a local single craft agreement. Certain local agreements can be multi-craft agreements. All of the local unions of a particular craft in the United States report to and are a part of a governing national body called the international union for that craft. If the agreement is made directly with the international union, it is binding on all of the local unions throughout the country and is called a national agreement.

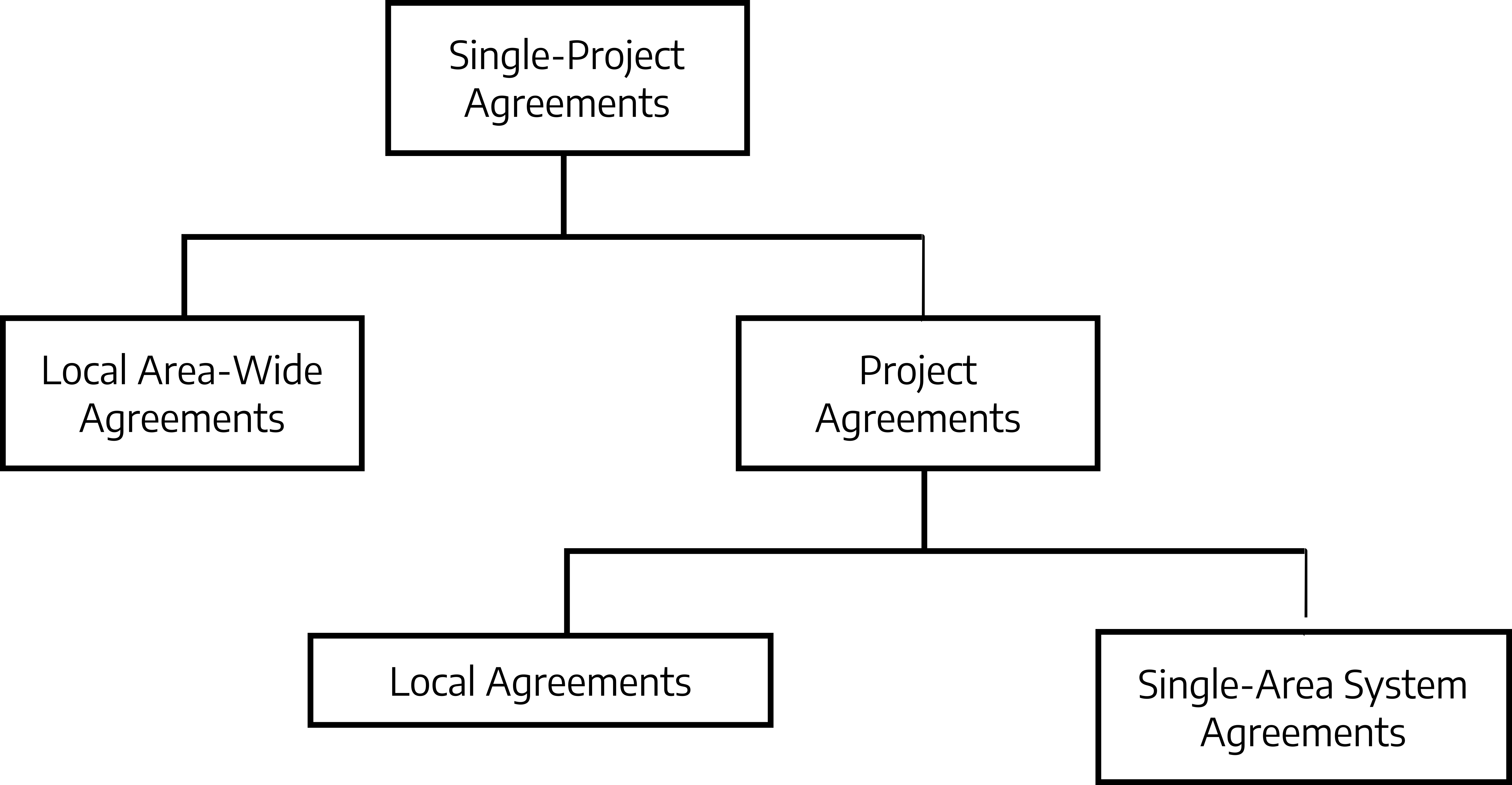

Local agreements can be subdivided into a number of categories expanding the second relationship tree as shown in Figure 6-5.

A local area-wide agreement is one that applies to the full geographical limit of the particular local’s territory, which might be limited to a particular county (or counties) within a state, to the entire state, or, in a few instances, to a group of several states. A project agreement is one that applies to a particular project named in the agreement and to no others. Some projects consist of just one construction prime contract, and a “single project” agreement would be applied to that single job only. An excellent example of this type of project agreement was one negotiated between the contractor joint venture partners who constructed the Stanislaus North Fork Project in central California a few years ago.[1] This agreement was negotiated with all of the basic crafts expected to be employed on the project and applied only to that project. The terms and conditions of the agreement were considerably more favorable to the contractor employer than other local agreements in existence in that section of California at that time. When the project work was completed, the agreement automatically terminated.

Some large projects amount to an infrastructure system built by a number of similar prime construction contracts over a number of years, and a single-area system agreement is an agreement that would apply to each of the separate projects within that system and to them only. The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District subway was constructed under a single-area system agreement in the late 1960s and 1970s, and the Los Angeles Area Rapid Transit District subway and the Boston Harbor Project for tunnel work and sewerage treatment plant construction in Massachusetts were both built under these types of agreements.

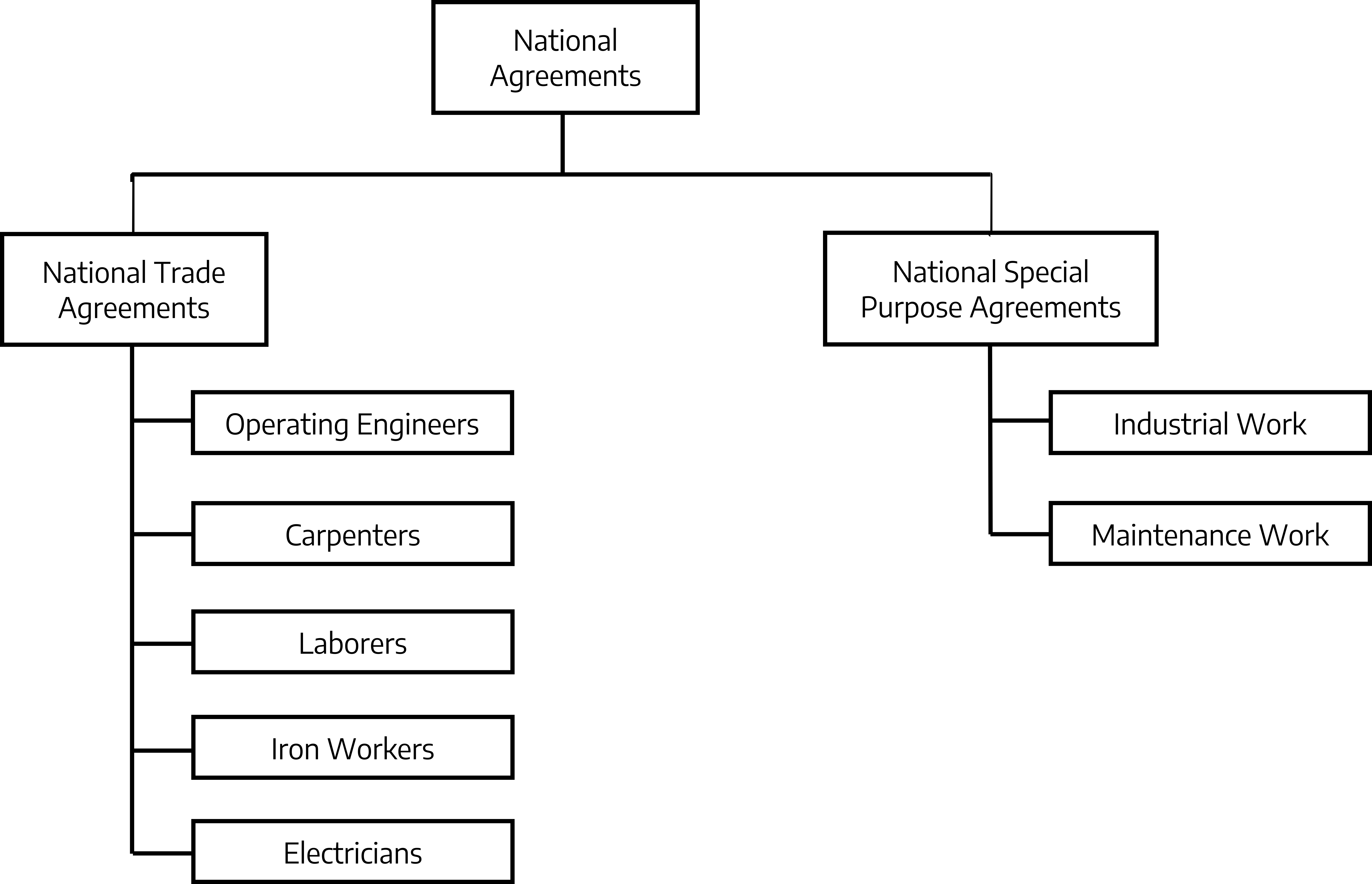

National agreements can be subdivided into national trade agreements and national special purpose agreements, further expanding the second relationship tree as indicated in Figure 6-6.

National trade agreements apply nationwide between the signatory employer and every local union for the particular trade, regardless of location. Currently, many contractor employers hold national trade agreements with each of the basic crafts and/or the various specialty crafts. National special purpose agreements are those made across the trades where all of the signatory trades are engaged in a specific common and narrowly defined type of work, such as industrial work or purely maintenance activity. The industrial work agreement shown in Figure 6-6 applies to the construction of industrial facilities such as factories and plants. The maintenance work agreement, sometimes called the National President’s Maintenance Agreement, applies only to the performance of maintenance work in existing industrial facilities.

Previous chapters have dealt with various aspects of construction industry contracts. Are labor agreements contracts? Chapter 2 discussed the three elements necessary for contract formation, which are the offer, the acceptance, and the consideration. Where and in what form are these elements found in the labor agreement? The offer and the acceptance occur through a long series of offers and counteroffers constituting a classic example of a negotiation. Practically everyone has heard of “labor negotiations.” For unions and union employers, labor negotiations occur at regular cycles, either annually or every two or three years. The productive capacity to perform construction work on the one hand, and the wage rates and fringe benefits stated in the labor agreement constitute the necessary consideration element. So, labor agreements are very much contracts and are subject to the same laws and rules of interpretation as are other contracts.

Labor Agreement Threshold “Red Flag” Provisions

As in prime construction contracts, labor agreements between contractor employers and labor unions contain “red flag” provisions. The threshold provisions include the following:

- Union security provisions

- Union jurisdiction

- Hiring hall provisions

- Grievance procedures

- Work stoppage/lockout provisions

- Subcontracting clause

Union Security Provisions

Union security provisions establish that union membership is a condition of employment. For new employees who are not already union members, a set period of time (usually a matter of days) is also established within which they must join the union in order to remain employed. It should be noted that in the several “right-to-work” states in the United States, the requirement for union membership as a condition of employment is contrary to state law and cannot be legally enforced. This does not mean that labor unions are illegal in “right-to-work” states, only that membership in a union cannot be demanded as a condition of employment.

Union jurisdiction provisions deal with the scope of the agreement, both in terms of the work performed and the geographical extent of the agreement. They list the specific kinds of work that can be performed only by the union members and specify the geographical area covered by the agreement. Union jurisdiction provisions usually differ among the various separate union craft agreements in an area. The provisions commonly conflict, with each craft reserving or claiming the same work. Employers signatory to several agreements applying to a common construction project cannot meet all of these conflicting conditions. The problem is generally resolved by the employer conducting a “mark up” meeting at the start of the project where all items of work in the project are assigned to one craft or another in accordance with the traditional work practices in the area, known as area practice. Unions disagreeing with such assignments can file a protest with the National Joint Board for Settlement of Jurisdictional Disputes, a national body that will hold a hearing and either support the employer’s assignment or alter it. Most unions and union employer groups are stipulated to the Board, which means that they agree to abide by the Board decisions.

Hiring Hall Provisions

Labor agreements may contain a hiring hall provision. This is a critical provision for the contractor-employer since the specific requirements can have a significant effect on hiring flexibility. A typical hiring hall provision states that the union is the exclusive source of referrals to fill job openings. If the contractor needs to hire new employees, they must be requested from the union hiring hall. When there is no hiring hall provision, the contractor can fill job openings from other sources (“hire off the bank”), as long as the requirements of the union security provisions are met.

Significant differences can exist in the hiring hall provisions in different labor agreements. For example, some provisions give the union the right to designate foremen; in others, the employer has that right. Since foremen are the first level of management on any project, it is essential for the contractor to know who will control their selection. Also, in some hiring hall provisions, the employer has the right to bring in a specified number of key employees; in others, the contractor must rely solely on the labor force in the area of the project. Many contractors have developed a following of workers with proven skills who will move to a new area in order to maintain continuous employment. It is a significant advantage to the contractor to fill key positions with these long-term employees.

Grievance Procedures

Each labor agreement contains a set grievance procedure for settling disputes between the contractor and the union. This clause is analogous to the dispute resolution clause in a prime construction contract between a contractor and owner. It is obviously important to know exactly what steps will be taken at each point in this procedure as well as what will happen if initial efforts fail to produce a settlement, which leads directly to the next threshold provision: work stoppage/lockout provisions.

Work Stoppage/Lockout Provisions

Most labor agreements contain work stoppage and lockout provisions. These provisions provide that the union must continue work (no work stoppage) while a dispute is being settled and that the employer must continue to offer employment (no lockout). However, even if the agreement contains work stoppage and lockout provisions, the agreement may provide that the union may cease work if the workers are not being paid or if the work site is unsafe. When improperly used, this latter provision can lead to work stoppages on spurious grounds in order to pressure contractor employers during disputes. A dispute over the exact pay rate in a particular case, or similar arguments concerning the amount that the workers are paid (as long as they are being paid some rate provided in the agreement), does not constitute sufficient grounds for the union to engage in a work stoppage. A work stoppage on these grounds would constitute a breach of the labor agreement. In these circumstances, the proper course of action for the union would be to file a grievance.

Subcontracting Clause

The effect of a subcontracting clause is to bind the contractor to employ only subcontractors who agree to the terms of the contractor’s labor agreement. The provisions of the clause will not necessarily require that a subcontractor actually sign a similar agreement with the union. They may only bind the subcontractor to abide by the terms and conditions of the contractor’s labor agreement and to make the required fringe benefit payments into the union trust funds. Much controversy has occurred over the inclusion of such clauses in labor agreements, since the requirement to use union subcontractors can make a prime contractor’s bid noncompetitive in areas where open-shop contractors are competing for the work. When the writer was managing a union contracting organization, bids were sometimes lost for this reason when open-shop competition existed.

Other “Red Flag” Provisions

In addition to the threshold provisions, the following “red flag” provisions, although secondary, are also important:

- Wage/benefits hourly rates

- Normal workday and workweek

- Overtime definition and pay premium

- Shift work definition and pay premium

- Work rules and manning provisions

- Steward provisions

- Me too/most favored nation provisions

Wage/Benefits Hourly Rates

The agreed-upon wage and fringe benefit rates obviously form the main body of the contract consideration and determine what the various crafts are to be paid. Usually, wage and fringe benefit rates are stated in terms of an amount per hour. An important point is whether the stated fringe amount per hour is to be paid on an hours-worked or on an hours-paid basis. Consider the following case:

Base rate: $17.50 per hour

Health and welfare: $1.50 per hour

Pension: $0.75 per hour

Vacation: $0.50 per hour

The question arises when a worker works overtime. For instance, if the overtime premium was time-and-a-half and the worker works 11 hours on a particular day, the respective amounts paid directly to the worker and paid into the union trust funds on an hours-worked basis would be

Worker gets: ($17.50) (8+ 1.5 X 3) = $17.50 x (12.5 hrs. paid) = $218.75

Trust funds get: ($1.50 + 0.75 + 0.50) x 11 hrs. worked = $2.75 x 11 = $30.25

On an hours-paid basis, the respective amounts paid to the worker and to the union trust funds would be

Worker gets: $218.75

Trust funds get: $2.75 x 12.5 hrs. paid = $34.38

The difference in total trust fund payments in this example of $34.38 – $30.25 = $4.13 amounts to 13.6% of the lower amount paid. A large amount of overtime on a major project can result in a considerable difference in the contractor’s labor costs depending on the method labor fringes are paid.

Normal Workday and Workweek

Workday and workweek provisions include clauses defining the standard workday, in terms of the number of hours worked (8 hours), the consecutive number of hours worked between starting time and lunch or dinner breaks, and the minimum required hours off between consecutive shifts worked by the same worker. They may also include defining the number of hours for “show-up time” to be paid if work is canceled after a person reports to work and then is sent home due to inclement weather, the minimum number of hours that a worker must be paid after starting to work, and similar rules that result in workers being paid for more hours than they actually work.

For example, it is not uncommon for workers who actually report to work and who are then sent home without performing any work at all to be paid a minimum of two hours at the straight time rate unless they had been advised by the contractor employer before they left their homes for work not to come to work that day due to inclement weather. Similarly, in such circumstances if workers actually were put to work on arriving at the jobsite at the start of the work shift and then were sent home due to inclement weather shortly thereafter, a minimum of four hours at the straight time rate commonly is required to be paid.

These provisions also establish the number of workdays that constitute a standard workweek (5 workdays) and a range of normal or standard starting and quitting times for each standard shift during the standard workday. Some labor agreements include guaranteed 40-hour-week clauses, which provide that workers are guaranteed 40 hours’ pay for the week once work is started on the first day in any one workweek. It matters not that work had to be suspended because of inclement weather or other circumstances completely beyond the control of the contractor employer. The workers still receive pay at the straight time rate for the entire week.

Overtime Definition and Pay Premium

Overtime definition and pay premium provisions establish a schedule of overtime pay rates, usually in terms of a multiple of the basic hourly pay rate (time-and-a-half, double time, or triple time). These provisions also define when the overtime rate is to be paid-for example, after so many hours worked in a day or week (8 hours per day or 40 hours per week). on weekends and holidays, or when the hours worked do not fall between normal shift starting and ending times. In special circumstances, provisions may be included that allow exceptions to what would otherwise be considered overtime work. For instance, some projects require work to be performed in the middle of the night only when no work is being performed during the other two shifts. This would be common in work performed in heavily trafficked streets in urban areas. In these circumstances, the contractor employer usually can obtain the union’s agreement to pay a wage rate for this night work that is higher than the straight time rate that would be paid if the work was performed on standard day shift but considerably less than the overtime rate that otherwise would be required to be paid.

Shift Work and Pay Premium

Shift work and pay premium provisions define standard work shifts (first, second, and third shifts or “day,” “swing,” and “graveyard” shifts) based on the particular hours during the day that the shift works. A typical arrangement would be day shift: 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. with a 1⁄2 hour meal break; swingshift: 4:30 p.m. to 12:30 a.m. with a 1⁄2 hour meal break; and graveyard shift: 12:30 a.m. to 8 a.m. with a 1⁄2 hour meal break. However, a particular range of times for starting each shift is usually stated. The provisions may also contain clauses requiring that once a swing or graveyard shift is started, the workers must continue to work and be paid for a full workweek, and the union must be given a minimum notice period before shift work is to start. This author has experienced contracts in some jurisdictions where the requirement for continued payment for workers on shift work throughout the full workweek was extremely costly. Once shift work was started in a given week, the crews involved had to be paid their shift work wages for the entire week, even though work was required to be suspended because of inclement weather or other circumstances beyond the control of the contractor employer.

The pay premium provisions for shift work are usually stated in terms of straight-time hours to be worked for eight hours’ straight-time pay. For example, a day-shift worker will work eight hours and receive eight hours’ pay; a swing-shift worker, seven-and-a-half hours for eight hours’ pay; and a graveyard-shift worker, only seven hours for eight hours’ pay. If a day-shift worker works ten hours, he or she would be paid eight hours’ straight time and two hours at the specified overtime rate. A swing-shift worker would be paid eight hours’ straight time and two-and-a-half hours at the specified overtime rate. A graveyard-shift worker would receive eight hours at straight time and three hours’ pay at the specified overtime rate. Such a scenario is a typical arrangement, but the specific premium pay provisions may vary from shift to shift and from agreement to agreement.

It should be clear from the preceding that such matters as overtime work and shift work must be very carefully managed when the labor agreement contains expensive provisions such as a guaranteed 40-hour-week clause, shift work clauses requiring pay for the entire week, and so on. Otherwise, costs will quickly get out of hand. Also, these provisions must be clearly understood when pricing construction work in advance of actual construction, as when formulating bids or proposals.

Work Rules and Manning Provisions

Every labor agreement will contain work rules and manning provisions. These address such issues as when foremen, general foremen, or master mechanics must be utilized; what number of workers are required for standard crews; and the requirements for employing apprentices and helpers. Some agreements are very restrictive and allow the contractor little flexibility in determining the number of workers that must be hired. Others give the contractor the right to determine crew sizes and to hire the workers as the contractor sees fit. These provisions and the presence or absence of restrictive productivity-limiting practices are of critical importance to the contractor. Construction work cannot be accurately priced or managed effectively without an intimate understanding of these matters.

The manning rules can take a number of different forms, many of which greatly limit the employer’s flexibility and result in hiring additional workers who are not actually needed to get the work done. Examples of such restrictive provisions include the following:

- When equipment is broken down and being repaired in the field, the regular equipment operator is required to be present to assist the mechanic who is assigned to make repairs, rather than operate another operable unit, even though the operator is not a mechanic and is of no practical assistance.

- An equipment operator may change equipment only one time during any one shift. This requirement is particularly onerous and expensive to the contractor–employer on small jobs with several pieces of equipment that are not required to be operated continuously. For instance, a contractor doing utility work might conceivably be using a small backhoe, a front-end loader, and a small dozer intermittently where each piece of equipment is only operated a few hours during the shift. Only one operator, capable of operating any of the three pieces of equipment, is required in order to perform the required work operations.[2] Nonetheless, in some jurisdictions, the contractor would be required to employ three operators even though it would not be possible to operate all three pieces of equipment simultaneously.

- An operator must be assigned for a stated number of pumps, compressors, or welding machines on the job, regardless of whether an operator is actually needed. In one instance in the eastern United States, this work rule has resulted in contractors utilizing an inefficient jet-eductor dewatering system instead of a more efficient deep well system because the work rules applicable to the project mandated that one operator was required around the clock for every three deep wells (of which a large number were required), whereas fewer operators were required for the jet-eductor system.

- Stated crew sizes must be used, such as a minimum of four or five in a piledriving crew when only three are actually needed to do the work.

- An oiler must be assigned to each crane over a stated size, whether or not an oiler is needed for the safe operation and maintenance of the crane. This frequently has resulted in an assignment of an oiler to a single operator center-mount crane even though an oiler is not needed and there is no place on the crane for the oiler to ride safely when the operator is driving the crane from one work location to another.

- Laborers must be assigned to assist carpenter crews at a stated number of laborers for a stated number of carpenters, regardless of how many laborers are actually needed.

- Laborers must be assigned to dewatering pumps, even when the pumps are electrically powered and automatically controlled so that they require little or no attention at all.

Steward Provisions

A labor agreement will usually contain provisions relating to the union shop steward, an individual appointed by the union to deal with the employer on behalf of the union employees at the site. The steward is not the same as the union business agent, who represents the union in dealing with all contractor employers within a certain area but who is not normally continually on the jobsite. The steward is employed by the contractor, ostensibly as a regular craft employee expected to do a normal day’s work. The steward provisions permit the steward to engage in union activities while on the job. A danger to the contractor is that overly permissive language in the agreement permits the steward to engage in full-time union activities and perform little or no work.

Me Too/Most Favored Nation Provisions

Me too/most favored nation provisions can be very expensive to the contractor. “Me too” clauses entitle a worker to be paid the highest overtime rate of any craft actually working overtime on that day, even though the rate in the worker’s union agreement is lower. Most favored nation provisions require that any clauses that are less favorable than similar clauses of subsequent agreements negotiated with another craft are replaced with the more favorable language of the later agreement with the other craft.

A telling example of the extra labor expense that can be generated by such clauses was a project in the eastern United States in which this author was involved a number of years ago. The project involved structural concrete work, requiring carpenters, operating engineers, laborers, and cement masons to be conducted simultaneously with excavation and ground support operations requiring operating engineers, piledrivers, and laborers. The labor agreements provided that all crafts on the job received overtime pay at time-and-a-half with the exception of the carpenters and piledrivers who received double time.[3] Frequently, concrete placements would run into the second shift with laborers, operating engineers, and cement masons being required for a number of hours at the overtime rate of time-and-a-half. Frequently, lagging crews, part of the ground support operation, were also required to work overtime to lag up ground that had been excavated during the day shift. This crew consisted of seven or eight laborers and one piledriver whose sole job was to cut the lagging boards to length with a chain saw so that the cut boards could be installed by the laborers. Thus, among all of the workers on overtime, sometimes totaling as many as 20, there was one piledriver. Because the piledriver was entitled to overtime at the double-time rate, each of the others was also required to be paid overtime at the double-time rate, even though their agreements called for overtime at the time-and-a-half rate.

Fortunately, for the good of the industry, such onerous provisions are antiquated today, and few labor agreements contain them. Many current labor agreements are fair and even-handed but, as the incidents just related indicate, each new agreement must be carefully read and understood to avoid unpleasant surprises.

Conclusion

This chapter presented a brief general survey of the types of labor agreements commonly in use in the United States today according to whom the employer and union parties are likely to be, the geographical limits of the agreements, and the general nature of the construction labor involved.

Also, the details of typical provisions found in labor agreements were discussed, particularly emphasizing those provisions of special importance to contractors when pricing and managing construction work.

Chapter 7 moves on to construction purchase orders and subcontract agreements. Both are additional examples of contracts closely related to the prime contract between the construction contractor and the owner.

Questions and Problems

- Define or explain the following relevant labor agreement terms:

- Single employer and multi-employer party

- Local and international unions

- Basic crafts and specialty crafts (name the six basic crafts)

- Local and national labor agreements

- Local area-wide agreements

- Project agreements-single project and single-area system agreements

- National trade agreements and national special purpose agreements

- Single craft and multi-craft agreements

- Do labor agreements contain the three elements of offer, acceptance, and consideration necessary for contract formation? How do the offer and acceptance typically occur? What parts of a labor agreement comprise the consideration element?

- What are the six threshold clauses usually found in a construction labor agreement? What is the general subject matter of each?

- What are three important aspects of hiring that may be contained in a hiring hall clause? What does “hiring off the bank” mean when the project is operating under a labor agreement? Do workers “hired off the bank” have to be union members or agree to become union members?

- What is a work stoppage? A lockout? What two circumstances will always be viewed by courts as justifying a union’s refusal to continue work? Would a dispute over the proper rate of pay qualify as constituting one of the preceding circumstances? Would such a dispute be subject to the procedure set forth under the grievance clause?

- What is the essential meaning of a subcontracting clause? What is the typical union position on subcontracting clauses? Why? What is the employer’s position? Why?

- What are the seven additional “red flag” clauses discussed in this chapter? What is the general subject matter of each?

- What is the distinction between payment of union benefits on an hours-worked basis and on an hours-paid basis? Under what circumstances on a project does this distinction become important?

- What is meant by a standard or normal workday? Standard or normal workweek? What is meant by “show-up time”? What is a shift? What does shift work mean? What is overtime? Overtime premium? How many hours of work comprise a standard (normal) straight time day shift? A swing shift? A graveyard shift? How many work shifts constitute a standard (normal) workweek? How many hours at the straight time rate are usually paid for the standard (normal) day shift? For swing shift? For graveyard shift?

- What are work rules? Manning provisions? What are the two examples of work rules-and five examples of manning provisions cited in this chapter?

- What is a steward? A business agent? Who pays each? Does a steward perform construction work on the project?

- What is a “me too” provision? A most favored nation provision?

- The following question assumes that you have access to an actual construction industry labor agreement. Refer to the particular labor agreement that you have and answer the following questions:

- Who is the union party? The employer party?

- Is the employer party a single party employer or a multi-party employer?

- Does the union party consist of basic crafts, specialty crafts, or a mixture of basic and specialty crafts?

- List every “red flag” provision discussed in this chapter that you can find in the labor agreement and cite the article number for each provision that you list.

- A project required 117,900 actual carpenter work-hours, of which 15% were performed on an overtime basis. The carpenter base pay was $27.50 per hour, and the total union fringes were $6.27 per hour. Overtime work was paid at double time. How much additional labor expense would the contractor employer incur if the union agreement called for payment of union fringes on an hours-paid basis rather than on an hours-worked basis?

- A project cost estimate indicates that the work will require an average of six crane operators for a total of 6,494 crane operator-hours and an average of nine other heavy-equipment operators for a total of 9,720 other heavy-equipment operator-hours. The estimate was made on the basis that all work would be performed on a one-shift-per-day, five-days-per-workweek basis. The climate at the site was such that 12% of the normal workdays in the five-day workweek were expected to be lost because of inclement weather. This fact was recognized in the anticipated project schedule. How much more labor cost would have to be anticipated for crane operators and heavy-equipment operators if the labor agreement for the project provided for a guaranteed 40-hour week for these particular operating engineer classifications and provided that labor fringes were to be paid on an hours-paid rather than an hours-worked basis than if the labor agreement did not contain these two provisions? The following wage rates applied:

Base Pay Fringes Crane operator $32.50 $6.82 Other heavy equipment operators $30.25 $6.82 -

Project work on a major Midwestern river was progressing on the basis of a normal eight-hour-day shift, five days per week. The owner directed the contractor to accelerate completion of a contractually mandated milestone for the project by putting the work crews on shift work, three shifts per day, five days per week. The work involved for the milestone required piledrivers and operating engineers. The labor costs per day for the total crew were $3,840 base pay and $768 union fringes per each eight-hour-day shift. The portion of the work to be accelerated would have required an additional 60 full eight-hour shifts of work or 60 x 8 = 480 crew-hours to complete. The project labor agreement provided for shift work but stated that once shift work was established at the beginning of the workweek, the crews must be paid for the entire week for each new week’s work started even if work were temporarily suspended later in the week because of inclement weather or otherwise. The labor agreement further provided that union fringes were to be paid on an hours-paid basis and that the day shift was to receive eight hours’ pay for eight hours’ work; the swing shift eight hours’ pay for seven-and-a-half hours’ work; and the graveyard shift eight hours’ pay for seven hours’ work. The acceleration order was issued in the middle of the winter when an average of four shifts per five-day workweek (two shifts on swing shift and two shifts on graveyard shift) could be expected to be lost because of extremely cold weather. Assuming that there would be no loss of efficiency for work performed on swing and graveyard shifts, determine how many days would be required to reach the milestone required by the acceleration order and what the extra labor cost for complying with the acceleration order would be.