16. Delays, Suspensions, and Terminations

Key Words and Concepts

- Time is of the essence

- Suspension of work

- Delay

- Increases in direct/time related costs

- Inefficiency due to interruptions of performance

- Excusable delay

- Compensable delay

- Contractual provisions for compensable delay

- The federal contract suspension of work clause

- No-damages-for-delay clauses

- Attitude of courts toward no-damages-for-delay clauses

- Contracts that are silent on delay

- Delay in early completion situations

- Root causes of delay and suspensions of work

- Importance of the notice requirement

- Constructive notice

- Difference of terminations from delays or suspensions of work

- Federal contract default termination clause

- Federal contract termination-for-convenience clause

- Genesis of termination-for-convenience clause

- Abuse of discretion

- Termination-for-convenience clause in other contracts

Delays and Suspensions of Work

Delays in construction contracting can be both psychologically and financially destructive, just as they are in everyday life. Whether the delay results from an act of God, breach of contract by one of the parties, or differing site conditions, its impact on construction contracts is often catastrophic. The old adage “time is money” is definitely true in these situations.

Time Is of the Essence

Construction prime contracts and subcontracts often contain a statement that “time is of the essence.” These words appear to mean that contract performance be started promptly and continue without interruption until completion within the specified time period. Taken absolutely literally, the words mean that the contractor or subcontractor has an absolute duty to perform all contract requirements with no delay whatsoever and is in breach of the contract for failing to complete the contract work within the contractually specified time. Similarly, these words also suggest that an owner who does not promptly review and approve shop drawings or promptly perform other contractually specified duties has breached the contract.

The common judicial view is not quite so stringent. Courts usually apply the time-is-of-the-essence concept only to delays in performance that are unreasonable. In this view, construction contracts by their very nature are so fraught with the possibility of delay that some delay is almost inevitable. Also, the clause is sometimes interpreted to mean that the contractor or subcontractor is required to meet time deadlines, but the owner or prime contractor in subcontract situations is not—that is, it is a “one-way street.” However, contractors, subcontractors, and owners would be well advised to act as though time-is-of-the-essence requirements will be strictly enforced with respect to their commitments to others. They would equally be wise not to count too heavily on reciprocal commitments made by others being strictly enforced.

Delays v. Suspensions of Work

Interruptions to work can result in either a delay or a suspension of work. A suspension of work results from a written directive of the owner to stop performance of all or part of the contract work. When this occurs, work on the entire project or on some discrete part of the project ceases entirely until the owner lifts the suspension. A delay differs from a suspension in two ways: First, a delay may be only a slowing down or a temporary interruption of the work without stopping it entirely. Second, whether a slowing down or a temporary interruption of work, a delay is triggered by something other than a formal directive from the owner to stop work. As with suspensions, delays can affect the entire project or only a discrete portion of it. Suspensions of work and delays can be caused by a variety of conditions-bad weather, strikes, equipment breakdowns, shortages of materials, changes, differing site conditions, or some act, or failure to act, of the owner separate from a directive to the contractor to stop work. Regardless of the cause, and whether within the control of the parties to the contract or not, suspensions and delays can be devastating for both parties to the contract.

The distinction between a suspension of work and a delay is a technical one. In the following discussion, the word delay indicates a loss of time, whether caused by a suspension of work or by some other delaying factor. Such delays result in increases to direct and indirect time-related costs for both the contractor and owner, with the magnitude of the cost increases depending on the extent of the suspension or delay. In addition to these increases in time-related costs, the contractor often experiences increases in direct costs due to inefficiencies caused by the interruption of performance.

The owner’s cost increases usually involve additional project administration costs since supervisory staff is on the job longer as well as consequential cost increases due to the project going on line later than anticipated. As any cost estimator knows, time-related costs have a tremendous impact on the overall cost of performance. The potential magnitude of these costs makes interruption in the performance of the work a very serious matter for both owner and contractor. There is no doubt that time is money in the construction contracting world.

Compensable v. Excusable Delay

Once contract time has been lost, a threshold question is whether the delay is compensable or excusable—that is, whether the contractor will be paid, or made whole, for the extra costs incurred as a result of the delay or whether only an extension of contract time will be granted.

An excusable delay is a non-compensable loss of time for which the contractor will receive an extension of time but no additional payment. Excusable delays are not the fault of either party to the contract. Although given an extension of time, the contractor must bear the costs associated with the delay. Since they are also absorbing time-related costs, the owner is also bearing the consequences of the delay. Thus, each party bears its own share of the costs of an excusable delay. Common examples of excusable delays include strikes, unless caused by the contractor’s breach of a labor contract or some act contrary to reasonable labor management and inclement weather over and above the normal inclement weather experienced at the project’s location.

A compensable delay entitles the contractor to both a time extension and to compensation for the extra costs caused by the delay. Unless the contract contains an enforceable no-damages-for-delay clause, an owner-caused delay is a compensable delay. It is also possible that some delays that would normally be excusable only may become compensable if they flow from an earlier compensable delay. An example is a case where an owner-caused delay resulted in follow-on work to be performed at a time in the year when normal weather-related delays are likely to occur, and when that work would have been completed before the inclement weather had the owner-caused delay not occurred. In this situation, the extra costs resulting from performing in the normal inclement weather, although ordinarily not compensable, become compensable.

Contractual Provisions for Compensable Delay

A contractor cannot reasonably expect to be paid for delays that are self-inflicted. On the other hand, one would expect that the contractor be compensated when the delay is caused by the owner. The extent to which the contractor is entitled to compensation for extra costs resulting from delays and suspensions varies according to the contractual provisions for compensable delay. Reading and understanding these provisions is critical to protection of the interests of both contractor and owner.

The Federal Suspension of Work Clause

The federal contract suspension of work clause reads as follows:

SUSPENSION OF WORK

-

The Contracting Officer may order the Contractor, in writing, to suspend, delay, or interrupt all or any part of the work of this contract for the period of time that the Contracting Officer determines appropriate for the convenience of the Government.

-

If the performance of all or any part of the work is, for an unreasonable period of time, suspended, delayed, or interrupted (1) by an act of the Contracting Officer in the administration of this contract, or (2) by the Contracting Officer’s failure to act within the time specified in this contract (or within a reasonable time if not specified), an adjustment shall be made for any increase in the cost of performance of this contract (excluding profit) necessarily caused by the unreasonable suspension, delay, or interruption and the contract modified in writing accordingly. However, no adjustment shall be made under this clause for any suspension, delay, or interruption to the extent that performance would have been so suspended, delayed, or interrupted by any other cause, including the fault or negligence of the Contractor or for which an equitable adjustment is provided for or excluded under any other term or condition of this contract.

-

A claim under this clause shall not be allowed (1) for any costs incurred more than 20 days before the Contractor shall have notified the Contracting Officer in writing of the act or failure to act involved (but this requirement shall not apply as to a claim resulting from a suspension order), and (2) unless the claim, in an amount stated, is asserted in writing as soon as practicable after the termination of the suspension, delay, or interruption, but not later than the date of final payment under the contract.[1]

Note that the clause first establishes the authority of the contracting officer to order the contractor to “suspend, delay, or interrupt all or part of the work…. ” Then, it promises that, if the performance of all or any part of the work is suspended, delayed, or interrupted for an “unreasonable” period of time by an act or failure to act of the contracting officer, an adjustment will be made for any increase in the cost of contract performance excluding profit.

A separate clause in the federal contract provides that the contracting officer will “extend the time for completing the work” for justifiable cause, which includes delay due to acts or failure to act of the government. The contractor must notify the contracting officer of the cause of the delay within ten days of its occurrence or within such further period of time before the date of final payment under the contract that may be granted by the contracting officer.

Thus, the federal contract provides that the contractor receive both the costs and an appropriate extension of contract time for delay caused by any government act or failure to act administratively in respect to contract changes, constructive changes, differing site conditions, and so on. Therefore, delays of this type are compensable delays under the terms of the federal contract.

Delays and Suspensions in Other Contracts

Although many federal contract provisions are widely copied throughout the industry, the federal delay provisions are often not contained in other contracts. The federal contract approach could be said to be at one end of the spectrum and contracts containing no-damages-for-delay clauses at the opposite end.

No-Damages-for-Delay Clauses

A typical no-damages-for-delay clause reads as follows:

NO DAMAGES FOR DELAY

The Contractor (Subcontractor) expressly agrees not to make, and hereby waives, any claim for damages on account of any delay, obstruction or hindrance for any cause whatsoever, including but not limited to the aforesaid causes, and agrees that its sole right and remedy in the case of any delay . . . shall be an extension of the time fixed for completion of the Work.

Under these provisions, the contractor’s or subcontractor’s relief in the event of delay “for any cause whatsoever” is limited to an extension of contract time for whatever period the delay can be shown to have extended overall contract performance. There is no cost adjustment. Taken literally, this clause means that the contractor receives no relief other than a time extension even in instances where the owner’s acts or failure to act, including the owner’s negligence, caused the delay. This provision is a classic example of an exculpatory clause.

Judicial Attitudes on No-Damages-for-Delay Clauses

Individual judicial response to no-damages-for-delay clauses has been mixed. Courts in some states are loath to enforce the clause because the contract documents are drafted by the owner and advertised on a “take it or leave it” basis, compelling the contractor to accept the clause or refrain from bidding. Contracts resulting from such bidding documents are called contracts of adhesion. Many feel that such contracts are bargains unfairly struck, particularly when the potential delay may be caused by some act or failure to act on the part of the owner. When the owner’s acts or omissions have been particularly egregious, courts often refuse to enforce the clause. However, this is not universally true. In the state of New York, for example, courts generally enforce no-damages-for-delay clauses on the reasoning that the bidding contractors were aware of the risks imposed by the clause and should have included sufficient contingencies in the bid to cover them. This mindset is totally opposite the thinking behind the differing site conditions clause and similar clauses where owners try to eliminate large bid contingencies by creating even-handed bidding conditions.

The following cases illustrate the courts’ uneven treatment of this issue. For example, the highest court of the state of New York held that a no-damages-for-delay clause prevented contractor recovery of even those damages caused by the owner’s active interference with the contractor’s work. The contractor completed its contract 28 months later than originally scheduled and attributed the delay to the city’s failure to coordinate its prime contractors and to interference with the sequence in timing of the contractor’s work. A trial court, hearing the contractor’s suit for $3.3 million, instructed the jury that the contractor could not recover unless the city’s active interference resulted from bad faith or deliberate intent, and the jury denied recovery. The Court of Appeals of New York upheld the trial court’s instructions, describing the no-damages-for-delay clause as “a perfectly common and acceptable business practice” that “clearly, directly and absolutely, barred recovery of delay damages.”[2]

Courts in Illinois and Iowa have ruled similarly. In the Illinois case, when the contractor received notice to proceed with construction of a new high school, the site was not ready. After the site became available, the owner began to issue a barrage of change orders that eventually totaled more than $2.1 million. In a lawsuit filed by the contractor to collect delay damages, an official of the owner testified that in order to avoid cost escalation, the contract had been awarded before all design decisions had been finalized. The architect’s field representatives testified that, although this was new construction, it resembled a remodeling job before it was completed. Nonetheless, the trial court denied recovery of delay damages. In affirming the trial court, the Appellant Court of Illinois held, “If the contract expressly provides for delay or if the right of recovery is expressly limited or precluded, then these provisions will control.” The court further opined:

Lombard’s experience with public construction projects should have enabled it to protect itself from risks by either increasing its bid or negotiating the deletion of this contractual provision…. In any event, the Commission bargained for the right to delay with the insertion of the no-damage provision.[3]

In the Iowa case, a contractor installing lighting and signs on a new interstate highway was not permitted to start work until two years after the contract was awarded because of delays by others in the construction of the highway. The Iowa Department of Transportation paid for cost escalation on certain materials but refused to compensate the contractor for the delay, relying on a no-damages-for-delay clause in the contract. The trial court directed a verdict for the Transportation Department, and the Supreme Court of Iowa upheld the directed verdict. Incredibly, the Supreme Court said:

There was no evidence that 2-year delays were unknown or even that they were uncommon in highway construction.[4]

Other courts have taken a more lenient view. In Missouri, a contract was awarded for the alteration of the superstructures of two bridges. Separate prime contracts had been let for the construction of the bridges’ substructures. The superstructure contractor received notice to proceed eight months before scheduled completion of the substructures, and to comply with the superstructure schedule, the contractor immediately placed mill orders and began steel fabrication. Because of a differing site condition problem, the substructure completion was delayed, and the superstructure contractor was forced to start field work 175 days behind schedule. The owner granted a 175-day time extension but refused to pay additional compensation, relying on a no-damages-for-delay clause included in the contract. At the subsequent trial, it was found that when the notice to proceed was issued, the owner was aware of the differing site condition problem and the likelihood that the substructure contractor would be delayed. A federal district court awarded the superstructure contractor substantial delay damages, and the U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed. Both courts held that active interference is a recognized exception to the enforceability of no-damages-for-delay provisions. The U.S. Court of Appeals further stated that active interference requires a willful bad faith act by the owner, which in this case had occurred because the owner knew that a delay by the substructure contractor was likely but nonetheless issued a notice to proceed to the superstructure contractor.[5]

In a Florida case, the contractor for the construction of a shopping center was delayed because the owner was late in providing necessary drawings and specifications and delayed executing change orders, even though written change authorization was required before the contractor could proceed with the work. The contract contained a no-damages-for-delay clause. The contract was completed behind schedule, and when the owner withheld final payment, the contractor sued for the contract balance plus damages incurred because of the owner-caused delay. In ruling for the contractor, the District Court of Appeal of Florida held that active interference by the project owner is a well-recognized exception to the enforceability of no-damages-for-delay clauses and that the owner’s unreasonable delay in issuing drawings and specifications and executing change orders amounted to active interference.[6]

Contracts With No Provisions for Delays

Some contracts are silent on the issue of damages for delay. They contain no express language that either establishes or denies the contractor’s right to be paid for the extra costs associated with owner-caused delays. Under these circumstances, the only way the contractor can recover the costs and lost time associated with owner-caused delays is through a lawsuit proving breach of contract on the part of the owner. The particular breach that would have to be proved would be the breach of the owner’s implied warranty not to impede or interfere with the contractor’s performance (see Chapter 13). Although a heavy burden, this is a far better situation for the contractor than if the contract contained a no-damages-for-delay clause. Of course, for the contractor, the best contract contains fair and equitable provisions promising compensation for costs and time extension for delays caused by the owner.

Delay in Early Completion Situations

Occasionally, a contractor makes a claim for recovery of extra costs resulting from a suspension, delay, or interruption of work by the owner even though all the contract work is completed by or before the contractually specified completion date. In delay in early completion situations, is the contractor entitled to be paid delay costs?

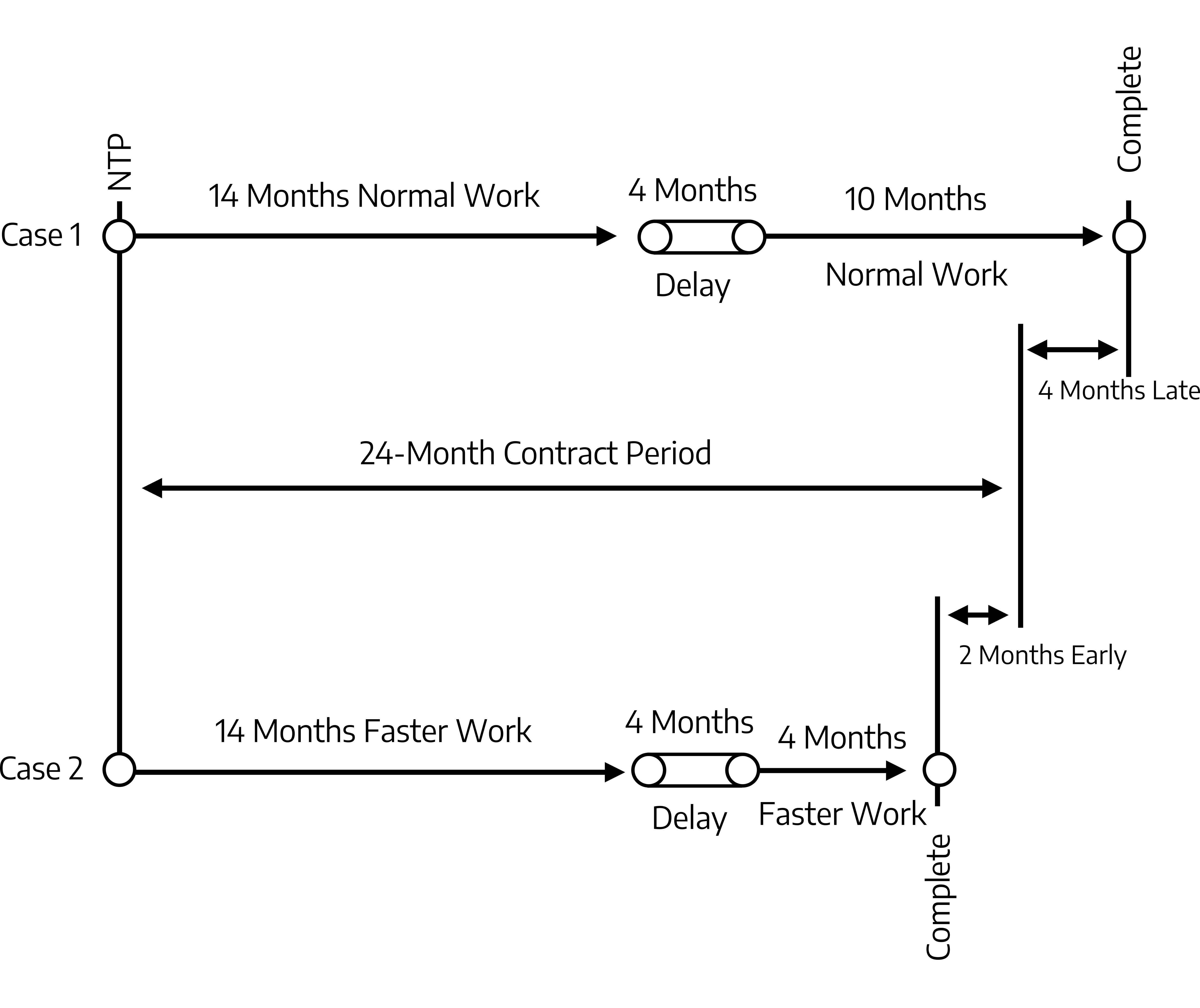

This question can be illustrated by comparing this situation to one in which the delay causes the contract to be completed after the specified contract completion date (see Figure 16-1). In the first case, after working for 14 months at a pace sufficient to meet contract requirements, the contractor was delayed for four months. Performance then continued at the pre-delay pace, and the project was completed four months late. Without the delay, the project would have been completed on time. If the delay was caused by the owner and the contract does not contain a no-damages-for-delay clause, the contractor is entitled to the extra costs for the four-month delay as well as a four-month time extension.

In the second case, the contractor worked 14 months at a pace faster than that required to meet the 24-month contractual requirement when the four-month delay occurred. Following the delay, the contractor progressed at this same pace for four additional months and finished the contract in 22 months, two months early. In this situation, it is more difficult for the contractor to sustain a claim for damages. Many owners take the position that, since the contractor finished the contract early, there was no damage caused by the delay, and, thus, the contractor is not entitled to either a time extension or extra costs. Presumably, these owners consider that the contractor’s bid was based, or should have been based, on taking the full allowable time for contract completion and, since performance was not delayed beyond the time allowed for completion, the contractor is due nothing.

The weakness of this position is that the contractor accepted all risk of performance of the contract and, in the absence of an owner-caused delay, would be liable for all extra time-related costs if the contract was not finished on time as well as for any contractually mandated liquidated damages. It cannot then reasonably be argued that the contractor should not also be entitled to save costs by finishing the work earlier than required by the contract if able to do so. Therefore, the owner causing a four-month delay is liable for the resulting extra costs to the contractor even though the contractor finishes the contract work early.

In this case, the contractor also should have been given a four-month extension of time at the conclusion of the delay, extending the time allowed for contract performance to 28 months after notice to proceed. Had the contract been extended in this manner, the contractor finished six months early, just as would have been the case if there had been no owner-caused delay. If not prohibited from doing so by explicit contract language, the contractor has the right to complete the contract early and, if prevented from doing so by an owner-caused four-month delay, as in this case, is entitled to be paid any extra incurred costs due to the delay.

Federal case law and most state law is highly supportive of the preceding principle. The Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals ruled in a 1982 case that a contractor had the right to complete the contract ahead of schedule and the government was liable for preventing or hindering early completion. A contract for the renovation of military buildings provided that the government was to arrange access to the individual buildings within two weeks of the contractor’s request for access. The government failed to provide access within the time specified for several of the buildings. Even though completing the project in less than the contractually stipulated time, the contractor submitted a claim for delay damages. The board said:

Barring express restrictions in the contract to the contrary, the construction contractor has the right to proceed according to his own job capabilities at a better rate of progress than represented by his own schedule. The government may not hinder or prevent earlier completion without incurring liability.[7]

In another federal case, an excavation contractor had submitted a schedule showing project completion in February, indicating the intention to work under winter conditions. However, the contractor’s in-house schedule, based on more optimistic production, indicated much earlier project completion. The contractor was achieving its in-house schedule, but when the quantity of unclassified material to be excavated overran the estimated bid quantity by 41%, the contractor was prevented from completing excavation before the winter season, forcing them to shut down until spring. The government denied the contractor’s claim for delay damages on the grounds that the submitted schedule indicated working under winter conditions. The U.S. Court of Claims (now the United States Court of Federal Claims) held that it did not matter that the contractor had not informed the government of its intended schedule. The court stated:

There is no incentive for a contractor to submit projections reflecting an early completion date. The government bases its progress payments on the amount of work completed each month, relative to the contractor’s proposed progress charts. A contractor which submits proposed progress charts using all the time in the contract, and which demonstrates that work is moving along ahead of schedule will receive full and timely payments. If such a contractor falls behind its true intended schedule, i.e., its accelerated schedule, it will still receive full and timely progress payments, so long as it does not fall behind the progress schedule which it submitted to the government.

On the other hand, if a contractor which intended to finish early reflected such intention in its proposed progress charts, it would have to meet that accelerated schedule in order to receive full and timely progress payments; any slowdown might deprive the contractor of such payments even if the contractor is performing efficiently enough to finish within the time allotted in the contract. In short, a contractor cannot lose when it projects that it will use all the time allowed, but it can be hurt by projecting early completion.[8]

Owners have more difficulty understanding their liability when they are not aware that the contractor intends to finish the work early. Contractors are therefore well advised to put the owner on notice formally whenever they are planning to complete the contract work earlier than required by the contract even though, as the preceding Court of Claims decision demonstrates, there is no contractual requirement to do so. Although not stated in the court decision, even if the contractor informs the owner that they intend to finish early, they retain the contractual right to revert to the original completion date if future events should force a change in plan.

There are exceptions to these rules. Some contracts contain explicit provisions that, although not prohibiting early completion, make clear that the owner will only be responsible for otherwise compensable delay costs or time extensions for delays that extend contract performance beyond the contractually stipulated date. For instance, contracts for subway construction in Los Angeles and a tunnel contract on the Boston Harbor Project in Massachusetts contain contract provisions to this effect. The language in the Boston Harbor Project reads as follows:

An adjustment in Contract Time will be based solely upon net increases in the time required for the performance for completion of parts of the Work controlling achievement of the corresponding Contract Time(s) (Critical Path). However, even if the time required for the performance for completion of controlling parts of the Work is extended, an extension in Contract Time will not be granted until all of the available Total Float is consumed and performance for completion of controlling Work necessarily extends beyond the Contract Time.[9]

The contract separately provided that without an extension of contract time, there would be no extra payment for time-related costs.

When provisions of this kind are included in the contract, they will be enforced and the contractor will receive no compensation for delay damages when completing the contract early.

Causes for Delays and Suspensions of Work

What are the root causes of delays and suspensions of work? What causal events seem to occur again and again? The following are typical examples:

Defective Specifications

One of the most common causes of delay is defective specifications resulting from the application of the Spearin Doctrine. When the drawings and specifications contain errors or omissions, costly delays often result-first, in attempting to comply with the erroneous drawings and specifications and, second, in waiting for the errors to be corrected and revised drawings and specifications to be issued.

Site Availability Problems

Another common cause of delay is lack of site availability at the time the notice to proceed is issued. Unless the contract provides otherwise, the contractor is entitled to the full use of the site at the time of notice to proceed. If the site is not available at that time, the contractor may be delayed. Also, an owner’s failure to provide a reasonable means of access to the work or interruption of access previously provided may delay the contractor.

Changes and Differing Site Conditions

Delays are also caused by changes directed by the owner, including changes because of problems associated with encountering differing site conditions. Just the requirement to perform added work may delay completion of the contract, and additional time is often lost waiting for the architect or engineer to revise the drawings and specifications when changes are required. This is particularly true when differing site conditions are encountered.

Owner’s Failure to Act Administratively

The owner may delay the contractor by failing to act or by acting in a dilatory manner administratively. The contractor is entitled to expect reasonable promptness in performance of contractual acts required of the owner, such as approvals of shop drawings and so on. If the owner does not cooperate, the contractor is delayed. Problems also arise when the contractor needs additional information, instructions, or a directive to proceed in connection with changes or differing site conditions, and the owner either refuses or is unreasonably slow in providing the needed information, thus delaying the contractor.

Case law decisions previously cited in Chapters 13, 14, and 15 illustrate the courts’ handling of such causes of delay.

Notice Requirements

The federal suspension of work clause and the clauses in most other construction contracts that promise relief for the contractor in the event of suspensions, delays, or interruptions contain a stringent notice requirement. Several aspects of this requirement are important.

Purpose of the Notice Requirement

Usually the contractor is required to furnish written notice to the owner within a stated period of time following any event that the contractor contends has caused or will cause a delay. Without such notice, the owner may not know that some act or failure to act is delaying the contractor. The requirement is reasonable, and failure on the contractor’s part to comply with it may result in waiver of entitlement to relief.

A secondary reason for notice is to establish a start date for the delay. This reason applies to all delays, both compensable delays caused by the owner and excusable delays. Although not appreciated at the time, in case of dispute, the time extent of many delays may have to be decided by a court or arbitrator years after the event, and a record establishing the start date can be invaluable.

Case law decisions denying contractors’ recovery due to lack of notice are legend. For instance, the U.S. Court of Appeals denied any recovery for extra costs when a contractor encountered more subsurface rock than indicated in the contract documents because they failed to notify the owner within five days of any event that could give rise to a claim for additional compensation or an extension of time, as the contract required. The contractor’s claim, without prior notice of claim, was filed three months after completion of the work where the rock was encountered.[10]

Similarly, the Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals denied a contractor’s claim for extra compensation due to the poor condition of exterior surfaces on Navy housing units that were being painted. The claim was not raised until after the contractor had applied primer and finished coats to the surfaces. Once the surface had been primed and painted, there was no way for the government to evaluate or verify the contractor’s allegations.[11]

Constructive Notice

In some circumstances, the owner may be held to have received constructive notice of delay. For instance, if an act of God shuts down the work or the owner issues a written directive to suspend all work, the owner is presumed to be aware of the associated delay. Constructive notice means that, even though not specifically notified formally, the owner knows that the work is being delayed.

In Ohio, a contractor on a sewer construction project failed to give the owner notice when differing site conditions were encountered. The contractor had bid the project on the basis that it would be possible to bore a tunnel and jack the sewer pipe into place for most of the job, which would have been possible according to the soil boring logs contained in the contract documents. During the work, saturated silty sand was encountered, which had not been indicated in the boring logs, preventing the contractor from using the jacked-pipe method of construction. A far more expensive open-cut method was required. The owner’s representatives were present at the site throughout performance and were aware of the soil conditions encountered. Additionally, many meetings were held to discuss the problem, and extensive written correspondence passed between the contractor and the owner.

When the contractor submitted the claim under the differing site condition clause, the owner denied the claim on the grounds that timely notice had not been given as required by the contract. The Court of Appeals of Ohio ruled that the contractor’s claim was not barred by failure to give written notice because the owner through its on-site representatives knew of the conditions, which served as constructive notice of the situation. In the words of the court:

There is no reason to deny the claim for lack of written notice if the District was aware of differing soil conditions throughout the job and had a proper opportunity to investigate and act on its knowledge, as a purpose of formal notice would thereby have been fulfilled.[12]

Although most courts would probably rule as the Ohio court did in similar circumstances, the contractor should always promptly give written notice of a delay to the owner.

Terminations

There is an obvious difference between terminations and suspensions or delays. Suspensions or delays mean a slowing of work or a cessation of work that is temporary in nature. However, terminations mean the cessation is permanent. Some construction contracts contain provisions where, under circumstances stated in the contract, both the owner and the contractor may terminate the contract, but the following discussion refers only to situations in which the contract is unilaterally terminated by the owner.

Requirement for an Enabling Clause

The owner’s right to terminate the contract depends on the existence of a specific clause in the contract giving the owner that right. Practically all construction contracts contain clauses permitting the owner to terminate the contract when the contractor is not meeting the contract requirements. Such terminations are called default terminations. Today, most contracts also contain a clause permitting termination for the convenience of the owner. In both cases, specific contract clauses establish the owner’s right to take the termination action.

Default Terminations

The federal contract default termination clause provides in pertinent part:

DEFAULT (FIXED-PRICE CONSTRUCTION)

-

If the Contractor refuses or fails to prosecute the work or any separable part, with the diligence that will insure its completion within the time specified in this contract including any extension, or fails to complete the work within this time, the Government may, by written notice to the Contractor, terminate the right to proceed with the work (or the separable part of the work) that has been delayed. In this event, the Government may take over the work and complete it by contract or otherwise, and may take possession of and use any materials, appliances, and plant on the work site necessary for completing the work. The Contractor and its sureties shall be liable for any damage to the Government resulting from the Contractor’s refusal or failure to complete the work within the specified time, whether or not the Contractor’s right to proceed with the work is terminated. This liability includes any increased costs incurred by the Government in completing the work….[13]

This contract language provides very strong rights to the government in order to protect the public interest when a contractor fails to meet the obligations of the contract. The contractor loses any further right to proceed and, together with the surety, is liable for all excess costs that the government may incur in completing the contract. Default termination language in other contracts contains similar provisions.

The consequences of default terminations are so severe that this step should be taken only in extreme situations. The attitude of our federal courts on this point is clear in the following citations from typical case law:

Termination for default is a drastic action which should only be imposed on the basis of solid evidence.[14]

It should be observed that terminations for default are a harsh measure and being a species of forfeiture, they are strictly construed.[15]

Convenience Terminations

The federal fixed-priced contract termination-for-convenience clause reads as follows:

TERMINATION FOR CONVENIENCE OF THE GOVERNMENT (FIXED-PRICE)

-

The Government may terminate performance of work under this contract in whole or, from time to time, in part if the Contracting Officer determines that a termination is in the Government’s interest. The Contracting Officer shall terminate by delivering to the Contractor a Notice of Termination specifying the extent of termination and the effective date.

-

After receipt of a Notice of Termination, and except as directed by the Contracting Officer, the Contractor shall immediately proceed with the following obligations, regardless of any delay in determining or adjusting any amounts due under this clause:

-

Stop work as specified in the notice.

-

Place no further subcontracts or orders (referred to as subcontracts in this clause) for materials, services, or facilities, except as necessary to complete the continued portion of the contract.

-

Terminate all subcontracts to the extent they relate to the work terminated.

-

Assign to the Government, as directed by the Contracting Officer, all right, title, and interest of the Contractor under the subcontracts terminated, in which case the Government shall have the right to settle or to pay any termination settlement proposal arising out of those terminations.

-

With approval or ratification to the extent required by the Contracting Officer, settle all outstanding liabilities and termination settlement proposals arising from the termination of subcontracts; the approval or ratification will be final for purposes of this clause.

-

As directed by the Contracting Officer, transfer title and deliver to the Government (i) the fabricated or unfabricated parts, work in process, completed work, supplies, and other material produced or acquired for the work terminated, and (ii) the completed or partially completed plans, drawings, information, and other property that, if the contract had been completed, would be required to be furnished to the Government.

-

Complete performance of the work not terminated.

-

Take any action that may be necessary, or that the Contracting Officer may direct, for the protection and preservation of the property related to this contract that is in the possession of the Contractor and in which the Government has or may acquire an interest.

-

Use its best efforts to sell, as directed or authorized by the Contracting Officer, any property of the types referred to in subparagraph (b)(6) of this clause; provided, however, that the Contractor (i) is not required to extend credit to any purchaser and (ii) may acquire the property under the conditions prescribed by, and at prices approved by, the Contracting Officer. The proceeds of any transfer or disposition will be applied to reduce any payments to be made by the Government under this contract, credited to the price or cost of the work or paid in any other manner directed by the Contracting Officer….[16]

-

The genesis of the termination-for-convenience clause dates back to the end of the Civil War when the cessation of hostilities placed the government in the position of remaining contracted for supplies and equipment that were no longer needed. At that time, the general purpose of the clause was to permit the government to stop contract performance when a major change in circumstances obviated the need for further performance. Since the clause first appeared in federal contracts, a number of federal court and board decisions have broadened its use to the point of permitting the government to terminate a contract for practically any reason, providing that the government acts in good faith. More recently, several federal court and board decisions have been more restrictive to prevent the contracting officer’s abuse of discretion when invoking the clause. In most instances today, the clause is invoked for legitimate reasons, and abuse of discretion cases are relatively rare.

Further actions that the contractor should take when the clause is invoked are fully spelled out in succeeding paragraphs of the federal clause (not cited here). A procedure is established for the contractor to make a monetary claim to the government for an equitable adjustment to settle the contract fairly. Generally speaking, such termination settlements reimburse the contractor for all costs incurred, including settlement costs with subcontractors and suppliers plus a reasonable profit thereon. Anticipated profit on the unperformed terminated work is not allowed.

Termination-for-convenience clauses in other contracts may or may not follow the line of the federal clause. A prudent contractor should be particularly interested in the provisions in these clauses governing how the contract will be settled in a termination-for-convenience situation.

Conclusion

Closely related to delays, suspensions of work, and terminations are the subjects of liquidated damages, force majeure, and time extensions. These topics are discussed in the next chapter.

Questions and Problems

- Discuss the popular view and the judicial view of the meaning of the words “time is of the essence” in a construction contract, subcontract, or purchase order.

- What is the prudent view of time-is-of-the-essence language in a contract with respect to the following:

- Your contractual commitments to others; and

- Others’ contractual commitments to you.

- Explain two differences between a “delay” and a “suspension” of work.

- In what two ways does delay to a construction contract increase costs for both the contractor and owner?

- Explain the difference between an excusable delay and a compensable delay. State some common examples of excusable delay.

- Explain the principal provisions of the federal contract suspension of work clause.

- Explain the principal provisions of a typical no-damages-for-delay clause.

- Are no-damages-for-delay clauses universally enforceable?

- What is the reasoning of courts that

- Refuse to enforce no-damages-for-delay clauses?

- Do enforce no-damages-for-delay clauses?

- When the contract is silent on the subject of damages for delay, what course of action must a contractor follow to recover time and money lost caused by an owner’s delay when the owner refuses to grant additional time and money?

- Explain why a contractor is entitled to be paid for extra costs suffered because of an owner-caused delay when, in spite of the delay, the contractor finishes the contract on or before the contractually stipulated date. Under what circumstances is the contractor not entitled to be paid such costs when the contract is finished on or before the specified date?

- What can a contractor do in advance to enhance the chances of recovering costs incurred because of owner-caused delays when the contractor plans to finish before the contractually specified date?

- What are the four general root causes of delay discussed in this chapter?

- Explain two reasons for the importance of prompt written notice to the owner when the contractor has been delayed. Does the necessity for prompt written notice occur only when the owner is delaying the contractor or for excusable delays as well?

- Explain constructive notice. Does the fact that constructive notice may exist mean that the contractor should not also give prompt written notice?

- Explain how a termination differs from a delay or suspension of work.

- Name and explain the two types of terminations discussed in this chapter. Do they each require an enabling clause in the contract? Does the federal contract contain an enabling clause for each?

- What was the original reason behind the termination-for-convenience clause in the federal contract?

- Does current federal contract law allow the government the completely unfettered right to invoke the termination-for-convenience clause?

- What should be the primary concern of the contractor concerning termination-for-convenience clauses in contracts other than the federal contract?

- F.A.R. 52.242-14 48 C.F.R. 52.242-14 (Nov. 1996). ↵

- Kalisch-Jarcho, Inc. v. City of New York, 448 N.E.2d 413 (N.Y. 1983). ↵

- M. A. Lombard & Son Co. v. Public Building Commission of Chicago, 428 N.E.2d 889 (Ill. App. 1981). ↵

- Dickinson Co., Inc. v. Iowa State Dept. of Trans., 300 N.W.2d 112 (Iowa 1981). ↵

- United States Steel Corp. v. Missouri Pacific Railroad Co., 668 F.2d 435 (8th Cir. 1982). ↵

- Newberry Square Development Corp. v. Southern Landmark, Inc., 578 So.2d 750 (Fla. App. 1991). ↵

- Appeal of CWC, Inc., ASBCA No. 26432 (June 29, 1982). ↵

- Weaver-Bailey Contractors, Inc. v. United States, 19 Cl. Ct. 474 (1990). ↵

- MWRA Contract CP-151, General Conditions Article 11.12.1. ↵

- Galien Corp. v. MCI Telecommunications Corp., 12 F.3d. 465 (5th Cir. 1994). ↵

- Appeal of Lamar Construction Co., Inc., ASBCA No. 39593 (Feb. 6, 1992). ↵

- Roger J. Au & Son, Inc. v. Northeast Ohio Region Sewer District, 504 N.E.2d 1209 (Ohio App. 1986). ↵

- F.A.R. 52.249-10 48 C.F.R. 52.249-10 (Nov. 1996). ↵

- Mega Construction Co., Inc. v. United States, 29 Fed. Ct. 396 414 (1993). ↵

- Composite Laminates v. United States, 27 Fed. Ct. 310 (1992). ↵

- F.A.R. 52.24902 48 C.F.R. 52.249-2 (Nov. 1996). ↵