2. Contract Formation, Privity of Contract, and Other Contract Relationships

Key Words and Concepts

- Contract formation

- Offer

- Acceptance

- Consideration

- Offering entity’s standard terms and conditions

- Conflict with the prime contract bidding documents

- Counteroffer

- Negotiation

- Meeting of the minds

- Subcontractor listings in bids

- Nonenforceable contracts

- Privity of contract

- Third-party beneficiary theory

- Intended v. incidental beneficiary

- Multiple prime contracts

Chapter 1 discussed various sources of the rules by which the construction industry operates. One important source of these rules was found to be the actual contracts entered into by the various “players” or participating entities in the industry. The first part of this chapter will examine the concepts of contract formation followed by a discussion of privity of contract and other contract relationships.

What Constitutes a Contract?

Since contracts are so important in defining the rules by which the construction industry operates, it should be obvious that when two parties enter into a contractual relationship, each would know and acknowledge that fact. However, this is not always the case. When one of the parties denies that a contract exists, it becomes important to understand when, and how, legally binding contracts are formed. Three elements for contract formation are necessary: an offer, an acceptance, and consideration.

Offer

What is an offer? What is its essential nature? One legal authority has defined an offer as a manifestation of interest or willingness to enter into a bargain made in such a way that the receiving party will realize that furnishing unqualified acceptance will seal the bargain.[1] If the willingness to enter into a bargain is manifested so that the person to whom it is made is aware, or should be aware, that some further manifestation of willingness will be required before an unqualified acceptance would seal the bargain, then what has transpired is not an offer.[2] For example, a house painter who declares, “I’ll paint your house for a price of $3,000 during the third week of September, provided my other work will let me,” or words to that effect, has not made a binding legal offer because the manifestation of willingness is qualified or “hedged.”

What about the format of the offer? Is any particular format required? In the general case, no format is required as long as the offer meets reasonable standards of completeness and clarity. However, there are exceptions, the most prominent being the particular kind of offer occurring in construction that we refer to as a bid or a proposal. Bids and proposals are usually made in response to an advertised notice called an invitation for bid (IFB) or a request for proposals (RFP). Both an IFB and an RFP by their written terms usually require that the bid or proposal be in a specific format; if it is not, it is considered a “nonconforming” offer and will be rejected. Other than in situations where a format is specified, no mandatory format is required for an offer to be legally sufficient.

Does the offer have to be in writing? Generally, it does not—that is, a verbal offer that meets reasonable standards of completeness and clarity can be legally sufficient. Again, there are important exceptions. Bids and proposals made in response to advertised IFB or RFP notices invariably require written submissions. Also, offers for the sale of goods are governed by the provisions of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), which requires offers of over $500 value to be in writing. Other local statutes may impose requirements on commercial transactions within the jurisdiction of the locality including, in some instances. a requirement that an offer must be in writing to be legally binding. Other than these kinds of exceptions, a valid offer can be either written or oral.

In every case, whether written or oral, a legally binding offer must be clear. It must define or describe that which is being offered. In the previous simplistic example, there is a lot of difference between

“I’ll paint your house for a price of $3,000 during the third week of September provided my other work will let me.”

and

“I’ll paint your house for a price of $3,000. My price includes scraping off all existing loose, flaking paint to bare wood, priming bare wood with Sherwin-Williams exterior primer, and applying two coats of Sherwin-Williams exterior house enamel, colors of your choice, one for the body of the house and one for the trim. Glazing work or repair of downspouts and drains is not included. The work will commence the third week in September and be completed that week, weather permitting.”

The second version, even if it were expressed verbally, is probably sufficiently clear and definitive to constitute a valid legal offer. The first is not, completely aside from the presence of the qualification.

Moving on, what defines the duration of an offer? Put another way, once given, for how long is an offer good? Sometimes an explicit statement in an offer clarifies that the offer will be good for only the period stated. Also, when offers or bids are made pursuant to the terms and conditions of an IFB or an RFP, the period for which the bidder may be held to the terms of his or her offer will ordinarily be explicitly stated in the IFB or RFP. Other than in exceptions such as those just given, an offer will be deemed legally valid until it is formally withdrawn. If the offer is not formally withdrawn, it will be deemed valid for a reasonable time. Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted definition of a “reasonable time.” Reasonable time thus becomes what a judge or an arbitrator thinks is reasonable in a particular case should a dispute arise.

Offers can be withdrawn in at least two different ways of importance to construction practitioners. First, if the offer contains a statement establishing a fixed duration, withdrawal at the end of that stated period would be implicit. Second, an offer that does not contain a statement establishing a fixed duration can usually be unilaterally withdrawn by the person or entity making it at any time prior to acceptance.

A particular issue concerning offers commonly results in construction disputes—whether or not the offering entity’s standard terms and conditions are deemed applicable to an offer. Another word for standard terms and conditions is boilerplate. That is, the fine print typically appearing on the back of vendors’ sales offers that has been carefully drafted to their advantage. Obviously, if the face of the offer explicitly states that it includes the offeror’s standard terms and conditions, these would apply. In addition, even though not explicitly stated on the face of the offer, the offeror’s standard terms and conditions apply if it could be shown that the person to whom the offer was made knew about them through previous dealings with the offeror where such standard terms and conditions did apply. For instance, a contractor who had habitually purchased form lumber from a particular supplier and who knew about the supplier’s standard terms and conditions and had accepted them in the past probably would be held to that knowledge and acceptance in regard to a new offer, even though the face of the offer did not explicitly state that it was subject to the supplier’s standard terms and conditions.

Another issue unique to the construction industry is created when the subcontractor and supplier bids to prime contractors include standard terms and conditions that are in conflict with the prime contract bidding documents. This can occur even when these bids are stated to be in accordance with the prime contract bidding documents as illustrated in the following common bidding situation:

A subcontractor submits a bid to a prime contractor who, in tum, is submitting a prime bid to the owner in accordance with the prime contract bidding documents. The sub-bid states prominently on its face that it is submitted “in accordance with the prime contract bidding documents” or words to that effect. However, buried in the boilerplate on the back of the subcontractor’s quotation form is a statement that the sub-bid offer is good for a period of ten days and, if not accepted within this period, the subcontractor is not bound to the offer. The effective date of the sub-bid is the same as the date of the prime bid. The prime contract bidding documents require the prime bid to the owner to be held open for a period of 60 days. The prime contractor’s bid is the lowest, and the prime contractor is awarded the contract 45 days after the bid date and shortly thereafter attempts to enter into a subcontract with the subcontractor. The subcontractor refuses to honor the sub-bid on the grounds that the offer expired ten days after the date of the prime bid.

Now what? Clearly, the prime contractor was in no position to contract with the subcontractor until awarded the prime contract by the owner. How would this conflict be resolved?

The sub-bid was stated to be “in accordance with the prime contract bidding documents.” Thus, if it can be established that the subcontractor knew, or should have known, about the prime contract bidding provisions, those provisions would take precedence over the bidder’s standard terms and conditions. Chapter 7 deals with this completely unnecessary kind of conflict between prime contractors and their subcontractors and suppliers and explains how to avoid it.

Acceptance

Moving on to the acceptance, the second element that must exist to form a contract, a number of points are important. Obviously, for the acceptance to have any relevance and legal meaning, it must be an acceptance of whatever was offered. A form of acceptance that changes the offer in any significant respect is not an acceptance at all but a counteroffer. An exchange of offers and counter offers between two parties constitutes a negotiation. In a negotiation, only the final offer and acceptance matter in respect to contract formation. A contract between two parties cannot be legally binding until and unless there is meeting of the minds—that is, the mutual agreement is not made under duress—at the time the contract is formed. Both parties must understand and accept that they have mutually agreed to be bound by the same set of terms and conditions or, in other words, by the final offer and acceptance. The trouble starts when the parties later discover that they did not have a common understanding of the agreement. Such is the genesis of many construction contract disputes.

As in the case of the offer, the acceptance may normally be written or oral and, if written, may be in any format, providing that a true meeting of the minds results. The only exceptions are where written or specifically formatted acceptances are required by the terms of an IFB or an RFP, by local statute, or by state laws that have adopted the Uniform Commercial Code, which specifically requires that an acceptance be in writing.

The construction industry has also spawned a recurring dispute involving a question about acceptance found in no other line of commercial activity. The dispute arises when the advertised bidding documents require prime contractors to list the names of their subcontractors on the face of the prime bid, indicating that they have relied on those sub-bids and have incorporated them in the prime bid (see sub-bid listing laws discussed in Chapter 1). This type of requirement is fairly common and when present is ordinarily known and understood by both prime contractors and subcontractors prior to the sub-bids being given. Under these circumstances, subcontractors often contend that the prime contractor’s act of incorporating the sub-bid in the prime bid and listing the name of the subcontractor constitutes a legally binding acceptance of the sub-bid offer. Unfortunately, from the subcontractor’s point of view, courts and boards have generally held to the contrary—that is, in and of itself, the use of a sub-bid and the listing of the subcontractor by a prime contractor in the bid to an owner does not constitute a legally binding acceptance of that sub-bid. An acceptance of any offer, including sub-bids, must be communicated directly from the party to whom the offer was made to the party who made it rather than communicated indirectly through a third party (the owner). This holding may seem unfair, particularly when contrasted to the doctrine of promissory estoppel discussed in Chapter 12. Nonetheless, this has been the usual case law ruling whenever this question arises.

Consideration

The third and final element necessary for contract formation is the consideration. In construction, the consideration may be money, but not always. It can just as well be some other “cash good” thing, such as the discharge of an obligation that has a value. The value may not be great. The main point is that consideration for both parties to the contract must always be present in one form or another in order for a contract to be formed. One way to think of consideration is that each party must have a rational reason for entering into the contract and an expectation of receiving something of value for performing the contract satisfactorily. In a construction contract, the owner’s consideration is getting the project work performed and the contractor’s consideration is receiving the contract price.

Contract Must Not Be Contrary to Law—Nonenforceable Contracts

A binding contract can never be formed without the presence of the three necessary elements for contract formation explained previously. However, the undeniable presence of the offer, acceptance, and consideration does not always guarantee the existence of a binding legal contract. In addition, the contract must not contravene the law and, if a public contract, must not contravene or be contrary to public policy. For example, an otherwise valid contract to set fire to a building enabling the other party to the contract to collect the insurance would not be legally enforceable.

In a construction industry context, a more common situation arises in public work where an otherwise valid contract is entered into by a public official not legally empowered to contract for the work. Such circumstances can lead to cases where the contractor has performed the work in good faith and then been unable to secure payment.

A good illustration of normal contractual relationships being voided because the contract was illegal is afforded by an Alabama case where the contractor was not paid for extra work performed because the governor of the state had not approved the contract/change order as required by statute.[3] Another is a New York case where the contractor was not paid for work performed and was forced to pay back monies that had previously been paid, because the city commissioner who had awarded the contract was found to have been bribed.[4]

Privity of Contract and Other Contract Relationships

In construction contract disputes, the threshold question is: “Does a contractual relationship exist between the parties to the dispute?” As discussed in Chapter 1, two important kinds of liability are contract liability and tort liability. Contract liabilities arise whenever the provisions of a contract, whether express or implied, are breached (broken) by one of the parties to the contract.

Privity of Contract

Contract liability flows from the existence of a contract. Without a contract, there can be no contract liability and, consequently, no sustainable legal cause of action for breach of contract. Therefore, if a party has been damaged by another and seeks redress through a lawsuit under a theory of contract liability, that party must first establish the existence of a contract with the party who caused the damage by breaching that contract. The existence of such a contractual relationship is called privity of contract.

It is not uncommon for a construction contractor to sue architect/engineers or construction managers for alleged failure to properly perform their duties associated with the construction contract, although the contractor does not have a contract directly with them. Such lawsuits must be based on tort with the contractor claiming tortious interference with construction activities or negligence on the part of the architect/engineer or construction manager. In tort cases, a cause of action does not depend on the existence of a contract, so the privity of contract issue does not arise.

Third-Party Beneficiary Relationship

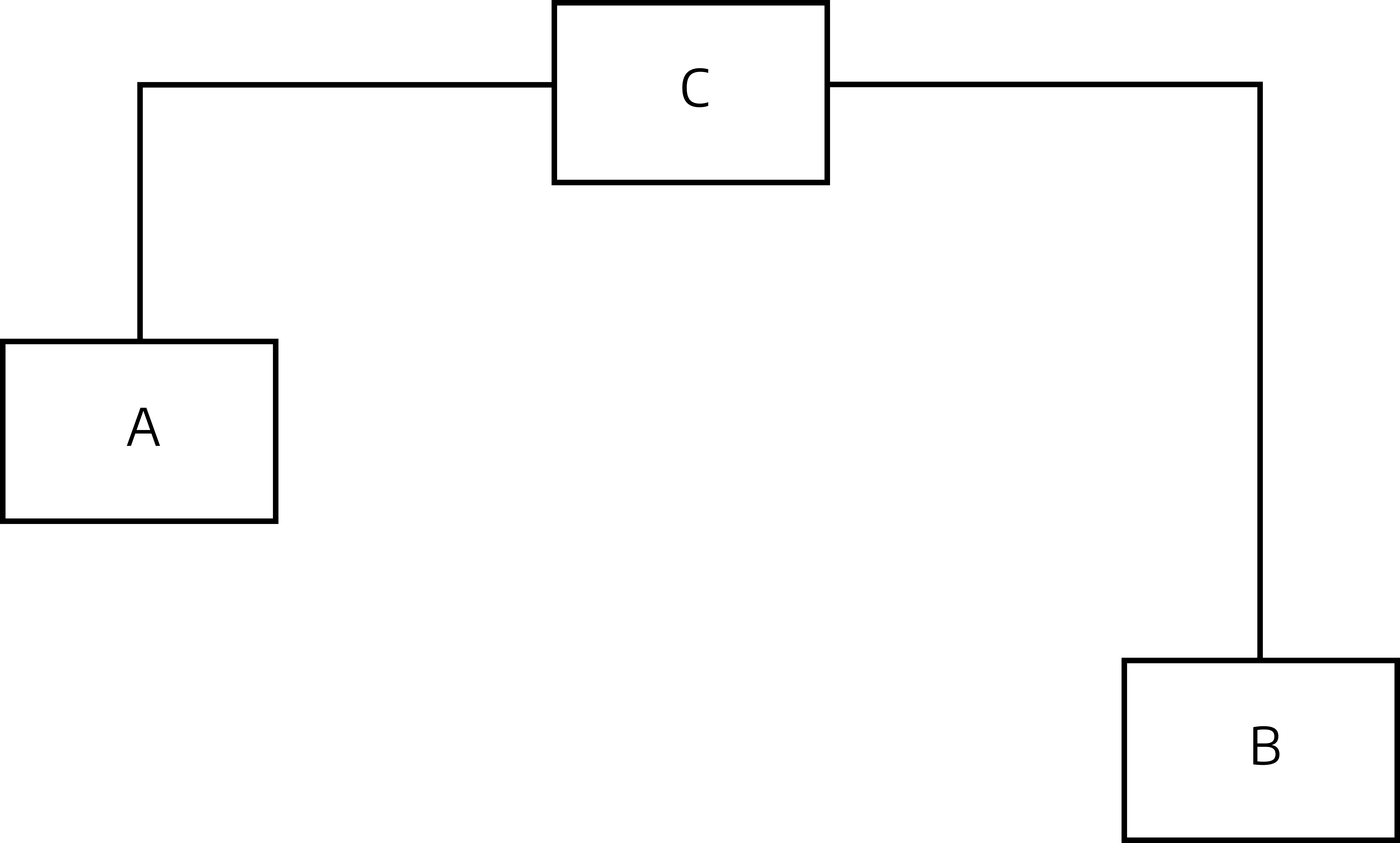

Contract or tort liability involving two parties is straightforward enough. However, a more complex situation sometimes arises in construction cases where lawsuits involving contract-type liabilities may be sustained against a party with whom one does not have a contract. Such lawsuits depend on the third-party beneficiary theory. The basic concept is that when each of two or more separate entities has a valid contract with a common third entity, they may be third-party beneficiaries of the contract between the “common” entity and the other noncommon entities. This relationship is illustrated in Figure 2-1.

In this situation, entity A has a valid contract with owner C, and entity B also has a valid contract with owner C. If the third-party beneficiary relationship is found to exist between entities A and B, A can sue B for damages suffered by A if B breaches some provision of B‘s contract with C. Likewise, B can sue A for damages suffered by B if A breaches some provision of A’s contract with C.

For example, suppose that an owner C has a loan agreement with bank B to advance funds to cover monthly approved estimates for work completed on a construction project. Owner C also has separately contracted with contractor A to construct the project according to approved drawings and specifications. All goes well until bank B stops advancing funds without legal justification, thus breaching B’s contract with owner C. Under these hypothetical circumstances, contractor A could probably successfully sue bank B and collect full payment for work completed on the argument that A was an intended third-party beneficiary of the bank’s contract with owner C, even though no contract existed between the contractor and the bank.

Third-Party Beneficiary Intent

The third-party beneficiary relationship illustrated in Figure 2-1 will be deemed to exist if it can be shown that the three parties had the intent to establish it when the contracts were formed. How can such an intent be shown? Obviously, if the wording of the contracts contains any explicit provisions establishing such intent, that intent would be deemed to exist.

Even though the contracts do not contain explicit language establishing intent, courts sometimes reasonably infer that the parties had that intent from the circumstances surrounding the particular contracts. In deciding whether to apply the third-party beneficiary rule, courts will make a careful distinction regarding the beneficiary relationship. It is not enough that one party may benefit from the fruits of the other’s contract with the common owner. Courts will also want to know whether the benefit was incidental or intended. A third-party beneficiary relationship that is merely incidental is insufficient to establish rights of recovery. On the other hand, an intended third-party beneficiary relationship will establish rights of recovery.

Suppose, for instance, that in the previous example the bank loan agreement did not state the proceeds of the loan were intended to finance the construction project and did not refer to the construction project in any other way. In those circumstances, a court might conclude that the construction contractor’s benefit from the loan proceeds was merely incidental rather than intended, thus denying the contractor rights of recovery.

Multiple Prime Contracts

A second common example is the multiple prime contractor situation. Suppose that civil works contractor A, mechanical contractor B, and electrical contractor C each contract directly with common owner D on the same project, requiring the work forces of all three contractors to be present on the site simultaneously. If the written or implied terms of each prime contract with owner D make little or no reference to the other prime contracts, and any one of the contractors A, B, or C damages one or more of the others through a breach of their individual contracts with owner D, the damaged contractor(s) would have no right of recovery directly against the contractor who caused the damage. The contracts with D do not establish an intended third-party beneficiary relationship. As discussed in Chapter 13 on contract breaches, the damaged contractor under the circumstances just described could well have a valid breach of contract cause of action against the owner for failing to manage or control the other prime contractors properly, but a lawsuit based on the third-party beneficiary rule would fail.

This principle is well-illustrated by an Illinois case where the appellate court ruled that a prime contractor on a multiple-prime contract could not sue one of the other prime contractors who had allegedly caused a delay because the multiple-prime contract documents did not create an affirmative duty toward other contractors on the site. There was no intended third-party beneficiary relationship. The court ruled, however, that the damaged contractor could sue the owner for failure “to properly supervise the construction project.”[5]

Years ago, the previous situation frequently occurred in projects involving multiple prime contracts. Now, owners often protect themselves from such breach of contract suits by inserting identical language in each prime contract stating that, if one of the prime contractors damages any of the others in the course of their individual contracts, the damaged contractors’ only recourse is to seek recovery directly from the contractor causing the damage. In no circumstances will the owner be responsible.

An excellent example of this latter approach was the policy of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) in administering the construction of the Boston Harbor Project, an immense sewerage collection and treatment project that is one of the largest projects of its type in the world. Approximately 30 or 40 separate prime contractors were engaged within a very confined site on Deer Island on the north end of Boston Harbor. These prime contracts contain precisely the kind of language just described, effectively insulating the MWRA from breach of contract claims from individual contractors alleging failure of the owner to properly control this virtual army of prime contractors working on the site.

The MWRA case is an example of the use of exculpatory clauses—or disclaimers—that lay off a liability that the owner would otherwise have. Under the circumstance described above, the intended third-party beneficiary relationship would be established and, if any of the prime contractors damaged any of the others through a breach of contract with the owner, the damaged contractor could directly sue the contractor causing the damage, even though privity of contract did not exist.

A Tennessee case illustrates the right of a co-prime contractor to sue another co-prime because the project bid documents provided that several prime contractors would be working on the site and that their progress schedules were to be “strictly observed.” In that case, the court felt that such language was sufficient to establish the third-party beneficiary relationship, because it implied that each contractor could rely on that requirement in the other’s contracts being complied with.[6]

In either of the multiple prime contract situations just described, if the behavior of the contractor causing the damage were so bad as to constitute disregard of a civil duty owed to the other primes, the damaged prime contractor would have legally sustainable grounds for suing in tort, which does not depend on privity of contract, as an alternative to the other available theories of recovery.

For example, if a civil work contractor unnecessarily and carelessly created excessive quantities of abrasive dust that interfered with a mechanical contractor’s assembly and installation of permanent machinery, the mechanical contractor would probably be successful in suing the civil work contractor in tort.

Conclusion

This chapter reviewed the elements necessary for contract formation from the perspective of the construction industry, the privity of contract concept, and the application of the third-party beneficiary relationship to common construction contracting situations. Chapter 3 will present an overview of prime construction-related contracts as an introduction to more detailed discussion of prime construction contracts presented in later chapters.

Questions and Problems

- What is an offer? Need it be in a particular format? Need it be in writing? Under what circumstances would a specific format be required? Under what circumstances would the offer have to be in writing?

- What does the issue of clarity have to do with the legal sufficiency of an offer?

- Must a legally sufficient offer necessarily contain an explicit statement of the time duration within which the offer may be accepted? Under what circumstances are explicit duration statements required? If a legally sufficient offer does not contain an explicit duration statement, how long would the offer be deemed to be open to acceptance?

- In what ways may an offer be withdrawn?

- Discuss the rules that determine when an offer in the construction industry is deemed to incorporate the offeror’s standard terms and conditions. Make clear the circumstances in which such an offer would be so deemed. Explain the usual rule that courts follow when an offer purported to be in accordance with bid plans and specifications is made by an entity whose standard terms and conditions conflict with the specified bid provisions.

- What is the fundamental requirement that a legally sufficient acceptance must meet? What is a purported acceptance that changes the terms of an offer called? Do the rules concerning the question of oral v. written form in the acceptance vary from those applying to offers?

- Discuss the usual court holding in the case of a subcontractor’s claim that a prime contractor’s listing of the subcontractor in the prime’s bid to the owner constitutes a legally binding acceptance by the prime of the subcontractor’s offer.

- Is the presence of consideration necessary for formation of a legally binding contract? Must the consideration be money? If not, what must it be?

- Under what two circumstances discussed in this chapter would a contract containing legally sufficient elements of offer, acceptance, and consideration be invalid and nonenforceable?

- What is the threshold question in breach of contract cases? What does privity of contract mean? Why is privity important?

- What two situations discussed in this chapter would permit a sustainable lawsuit where privity of contract would not matter?

- What rule will courts apply in deciding whether or not a claimed third-party beneficiary relationship exists?

- An owner has entered into separate prime construction contracts with contractor A, contractor B, and contractor C, all on the same construction project. Each contract contains similar provisions, none of which state any benefit that A, B, and C have as a result of the others’ contracts with the owner. None of the contracts refer to the others in any way. Although not negligent, contractor B falls far behind schedule in performance of the contract, which causes significant increases in the cost of performance of the separate contracts that contractors A and C have with the owner.

- Are contractors A and C likely to succeed in sustaining a lawsuit against B for damages suffered due to B’s failure to perform contract work in a timely manner? State the basis for your opinion.

- Assuming slightly different facts—namely, that B conducted contract operations in a grossly careless and unsafe manner that adversely affected A’s and C’s operations-respond to question (a), including the basis for your opinion.

- Second Restatement of Contracts § 24. ↵

- Id. § 26. ↵

- Rainer v. Tillett Bros. Const. Co., 381 So. 2d (Ala. 1980). ↵

- S.T. Grand, Inc. v. City of New York, 344 N.Y.S.2d 938 (N.Y. 1973). ↵

- J. F. Inc. v. S. M. Wilson & Co., 504 N.E.2d 1266 (Ill. App. 1987). ↵

- Moore Construction Co., Inc. v. Clarksville Department of Electricity, 707 S.W.2d 1 (Tenn. App. 1986). ↵