1. Interface of the Law with the Construction Industry

Key Words and Concepts

- Parties

- Common law

- Customs and practices of the construction industry

- Statutes

- Regulations

- Contractors

- Architect/engineers

- Owners

- Public owner

- Private owner

- Service and supply organizations

- Labor force

- Government in its regulatory capacity

- General public

- Construction document sequence

- National Labor Relations Act

- Davis-Bacon Act

- Lien laws

- Miller Act

- License laws

- Subcontractor listing laws

- Equal Employment and disadvantaged business opportunity laws

- Uniform Commercial Code

- Tort law

- Contract liability

- Express contract provisions

- Implied contract provisions

- Tort liability

- Statutory liability

- Strict liability Absolute liability

This book deals with the business and legal aspects of construction contracting practice from the perspective of a participating contractor. The word legal connotes the operation or existence of law. In what follows, law is meant to include federal- or state-enacted laws or statutes, the rules of federal and state regulatory bodies promulgated to give practical effect to enacted statutes, and the common law. Common law is that body of past court decisions, dating from the legal practice in England prior to American independence, that serves as authority or precedent governing future decisions. It can be thought of as “judge-made” law. Since judges have been, and continue to be, influenced by the customs and practices of the construction industry, these customs and practices in a sense are part of the law as well.

Before examining in detail the law as just defined, we should look into the various elements of the construction industry. Who is involved? Who are the players or—as one usually hears—who are the parties who in one way or another participate in the construction process?

The Typical Parties

Although others may be peripherally involved, the important parties certainly include the following major party groups.

Construction Contractors and Subcontractors

First, construction contractors and their subcontractors are obviously the key participants. These are the entities charged with the responsibility of actually putting construction work in place. That is, those entities who determine the means, methods, techniques. sequence, and procedures and direct the actual construction activities.

Architect/Engineers

The architect/engineer (A/E) who designs the work and often administers the construction phase of the project personifies the second important group of participants. These entities are the creators of the drawings and specifications for the planned construction.

Construction Owners

The construction owners for whom the work is done and without whom there would be no construction industry constitute the third important segment. This group is the source of the money that drives the industry. Construction contracts with private owners often operate very differently from those with public owners. For that reason, the distinction between private and public owners is important.

The private owner includes just about any person or entity that is not a local, state, or national governmental body. Examples include you or your neighbor who wants a home built and large commercial entities such as restaurant and retail chains, real estate developers, and the giant industrial corporations. The private sector also includes quasi-public bodies that may be regulated by state governments but are still private companies. Examples in the western United States include, among others, the Pacific Gas and Electric Company and Southern California Edison Company, which are regulated by the State of California Public Utilities Commission.

On the other hand, the public owner can be local, state, or federal governmental bodies. The public sector also includes entities created for specific purposes by actions of the voters, such as school districts, water supply and sewer districts, and transportation or transit authorities.

Service and Supply Organizations

A fourth segment consists of the service and supply organizations of the industry, such as the firms that manufacture and market construction equipment. Other examples include the producers of the basic materials of construction such as cement, concrete aggregates and other stone products, lumber and timber products, steel, petroleum products, and many other raw materials or manufactured items.

Insurance companies and sureties are service organizations. There is an important difference between the insurance and surety business, even though the same entity often engages in both, which is explained in Chapters 8 and 9.

What about banking institutions? Do you consider them to be important service organizations? If you understand the significance of the term “credit line,” you know the answer. Few owners or contractors could exist without the participation of the banks, which furnish construction loans for owners and equipment loans or operating capital loans for contractors.

Finally, the service and supply group of entities includes consultants and attorneys who furnish personal services or advice. Consultants include specialty designers for such requirements as dewatering and ground support systems, management consultants, scheduling consultants, construction claims consultants, and many others. Attorneys provide legal advice to the various parties involved in construction and represent them in court as well as in many business situations.

Labor Force

Another major category of participant is the labor force. Without this segment, nothing would get built. Labor force, as used here, means not only organized labor, consisting of international and local labor unions, but also that very large group of workers in this country who comprise the open shop or merit shop segment.

Local, State, and Federal Governments

Another category of player is local, state, and federal government, not in the previously discussed role as a construction owner, but in their regulatory capacity as the promulgators of many of the rules and regulations governing the operation of the industry.

General Public

Finally, that broad body of persons constituting the general public must be included. Construction does not occur in a vacuum, and large projects, particularly those in heavily populated areas, temporarily affect the lives of many persons who are not involved in the actual construction work but who are simply living or working in the area. The general public can greatly affect construction projects in two ways. First, construction planning must consider the impact on the public during actual construction. Second, planning must cover any permanent effects on the public, including the environment, which is also “public.”

The provision of large programs of general liability insurance speaks to the first question, and the increasing requirements for environmental impact assessments, which take place before actual construction work is permitted, attest to the second.

Rules for Participants

The major participants or players in the construction process have just been discussed. What constitutes or defines the manner in which these participants interact or should interact?

Contracts

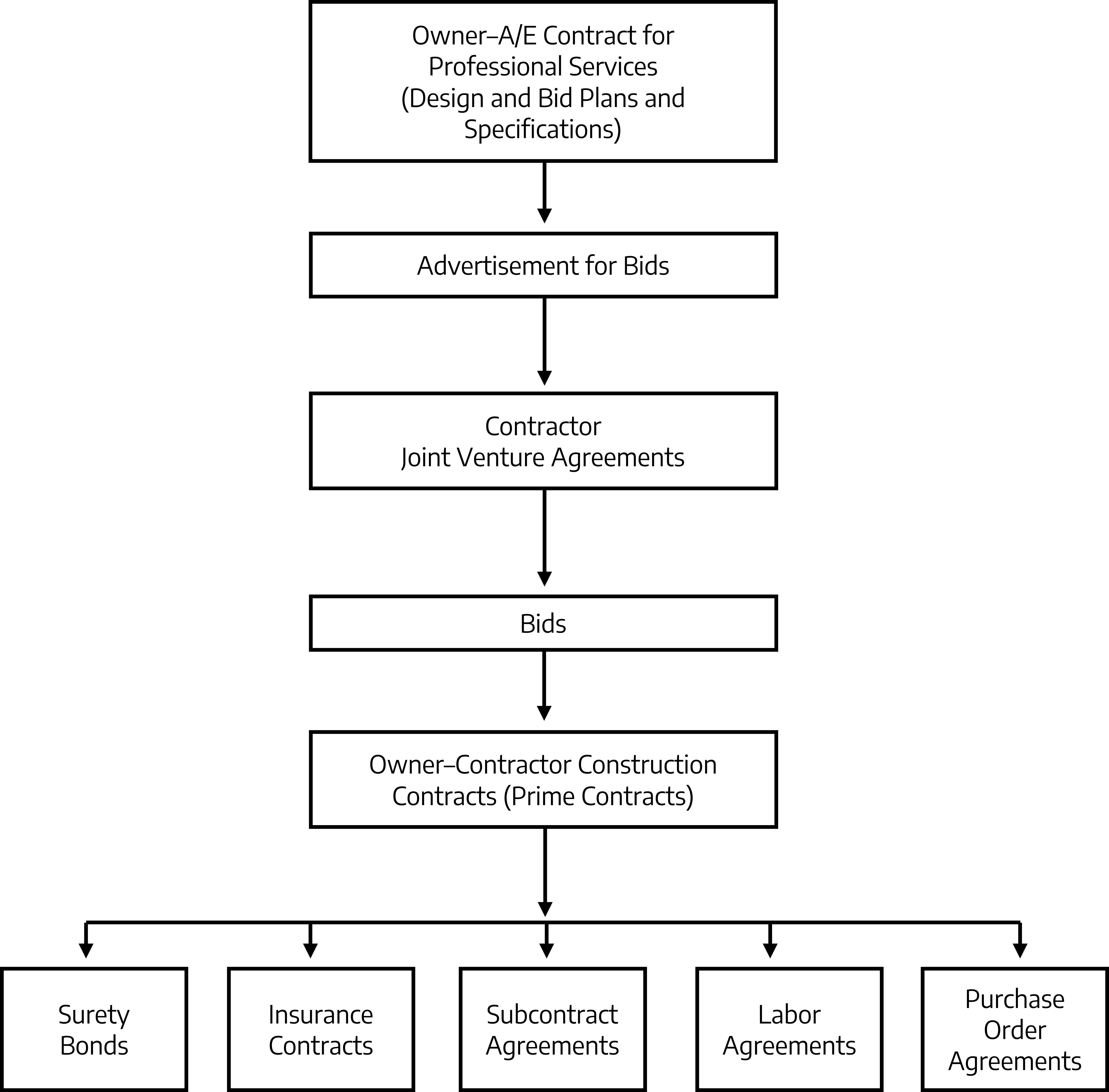

A primary body of rules for the conduct of the construction process is derived from the provisions of contracts and contract-related documents agreed to by participants in the industry. Figure 1-1 is a flowchart that represents the typical construction document sequence in which the more common contracts used in construction relate to each other.

The process typically starts with an owner who wants a project or a facility built. This person (or entity) signs a professional service contract with an architect/engineer to design the project and create a set of drawings and specifications. Next, the project is advertised for bids by a contract-related document called an advertisement. The advertisement often results in a pre-bid contract between one or more contractor bidders for the purpose of setting forth the terms of their agreement to submit a bid jointly and, if the bid is successful, to construct the project jointly. Such a contract between contractors is called a joint venture agreement. A contract-related offer to the owner to construct the project under stated commercial terms, submitted by a single contractor or joint venture contractor bidders, is the bid.

Bids are evaluated by the owner, eventually resulting in a prime construction contract to which the owner and the successful contractor or joint venture bidder are parties. The existence of the prime construction contract usually generates the need for surety bonds, insurance policies, subcontract agreements, labor agreements, and purchase order agreements, all of which are contracts that involve the prime contractor as a party. At this level, these secondary contracts, which flow from the existence of the prime construction contract and involve the prime contractor as a party, are called first-tier contracts.

If first-tier subcontract agreements are drawn up, they may generate a new family of second-tier surety bonds, insurance contracts, subcontract agreements, labor agreements, and purchase order agreements. In a similar manner, it is possible that a family of third-tier contracts may be generated.

Laws, Statutes, and Regulations of Governmental Agencies

A second important source of rules governing the construction process consists of three separate categories of laws, statutes, and regulations of governmental agencies.

The Federal Procurement Statutes are the source of basic rules and authority for the contracting regulations promulgated by the executive branch of the federal government. These statutes can be found in the United States Code (USC).

The Federal Regulations are the detailed rules for contracting by the federal government. These rules are currently called the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR). In addition, most federal agencies and subagencies have supplemented the FAR, resulting in the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) and the US. Army Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (AFARS). Subsubagencies have also created supplements such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (EFARS). These various regulations are published by the respective agency. Some of them are also published by commercial publishers such as the Commercial Clearing House (CCH), and most are published in the Federal Register and codified yearly in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).

State and local laws and ordinances are published and codified by the various states according to individual practices, which vary from state to state and municipality to municipality. Some of the more prominent federal and state laws include the following:

- National Labor Relations Act (the Wagner Act). This federal act is the primary law in the United States governing the relations between employers and their work force.

- Davis-Bacon Act. This federal act establishes minimum wage rates that must be paid on any federal project or on any project that is financed with a significant amount of federal funds.

- State Mechanic’s Lien Laws, the federal Miller Act, and the various state “little” Miller Acts. These state and federal laws operate to ensure that persons or entities providing labor or materials for construction projects receive the payment that they are due.

- State Contractor License Laws. A number of states have enacted laws that require persons or entities to demonstrate certain minimum qualifications, post a bond, and pass a qualification examination in order to operate a construction contracting business.

- State Subcontractor Listing Laws. A number of states have enacted laws to prevent “bid shopping,” a practice of some prime contractors that is unfair to subcontractors and material suppliers. In California, for instance, prime contractor bidders are required by law to list in their prime bid the name of the subcontractor, the type of work, and the subcontract price for every item of work that they intend to subcontract with a subcontract value greater than one-half of one percent of the prime contract bid price. Upon award of the prime contract, the prime contractor is then compelled to subcontract the listed work to the listed subcontractor at the listed subcontract price. The prime contractor is relieved of that obligation only if the named subcontractor is unable or unwilling to enter into a subcontract agreement with substantially the same terms and conditions as the prime contract, or, alternately, the prime contractor elects to perform the listed work with his or her own forces.

- Equal Employment Opportunity Laws, Disadvantaged Business, and Women-Owned Business Participation Laws, and Other Forms of “Set-Aside”Laws. These laws and the ensuing regulations at the city, state, and federal levels are intended to remedy past patterns of discrimination in employment and business opportunity based on ethnic origin or sex.

- Uniform Commercial Code. This code has been adopted by statute in virtually every state. Its primary purpose is to establish fair and uniform trade practices applying to the sale of goods as distinct from the performance of construction services. Nevertheless, the code has an enormous impact on the construction industry since so many of the “nuts-and-bolts” transactions in the industry involve the sale of goods.

Tort Law

The third and final contributor to the rules governing the conduct of construction operations is a body of the common law called tort law. What is a tort? Broadly speaking, a tort is a civil wrong. The central concept of tort law is that in living our daily lives we cannot with impunity, either intentionally or unintentionally, conduct our affairs in a manner that will injure or damage others.

Liability in the Construction Process

At this point, we have discussed the participants in the construction industry and briefly examined the sources of the rules for the construction scenario. A common thread throughout is the liability involved in practically all forms of construction-related activity. This thread consists of three broad classes of liability arising in one or more separate ways.

Contract Liability

The most prominent and obvious way a participant in the construction process becomes exposed to potential liability is by becoming a party to a legal contract. This first broad class of liability is called contract liability and results when a party to the contract breaches the contract by failing to conform to one or more of its provisions.

There are two basic kinds of contract provisions. The first is a provision that is plainly written in the text of the contract document itself. This type of provision is called an express contract provision. It is stated explicitly in the contract. Most people understand provisions that are stated prominently and clearly in black letters in the text of the contract document.

The second kind of contract provision flows from the contract but is not in the form of an explicit statement. These provisions come from time-tested, commonly held understandings that are implied by the contract. Such commonly held understandings are said to be implicit in the contract and are considered implied contract provisions—or implied warranties. An example of an implied warranty is that each party when entering into a contract implicitly warrants that he or she will not act, or fail to act, in a manner that interferes with the other parties’ ability to perform their duties under the contract. These commonly held understandings come both from the customs and practices of the construction industry and from past decisions of courts, known as case law, another term for “judge-made law” or “common law.”

Examples of both kinds of contract provisions are covered in later chapters. Breach of either kind results in contract liability.

Tort Liability

The second broad class of liability flowing to persons engaged in construction is tort liability based on tort law. The general tort concept, discussed earlier in this chapter, is part of the common law. Tort liability does not depend on the existence of a contract. Many individuals in all segments of the industry continually incur tort liability without realizing it because they mistakenly believe their liabilities are limited to those resulting from breach of the provisions in the contracts to which they are a party.

A second mistaken notion is that tort liability arises only when a person knowingly and intentionally acts in a manner that injures or damages another. Intentional acts that injure others certainly do create tort liability, but tort liability can also be created by an act that is unintentionally committed. An intentional tort would be to damage someone else’s property on purpose, whereas if the damage was caused because one was negligent, the tort would be unintentional. An intentional tort may constitute a criminal act in addition to a civil wrong, giving rise to criminal penalties as well as monetary damages.

Statutory Liability

The third broad class of liability is that imposed by law or statute and is called statutory liability. This class of liability flows directly from the provisions of enacted laws or statutes that apply in specific localities as well as from federal laws that apply throughout the United States. As is true with contract and tort liabilities, statutory liabilities may be either express or implied.

Strict Liability

Any form of liability, whether contract, tort, or statutory, is a serious matter to be avoided whenever possible. A frequently used second liability descriptor that can apply to all three broad classes of liability is strict liability, which means that it is not necessary to prove fault or negligence to establish that a person or entity is liable for some act or failure to act. The mere fact that the act or failure to act occurred is all that is necessary to establish the liability.

Strict liability is usually associated with tort liability situations, but it can apply to other classes of liability as well. For instance, express warranties that are frequently included in construction contracts also impose strict liability on the contractor in the event of failure to honor or make good the terms of the warranty. Such a warranty might provide, for instance, that the contractor warrants that a roof installed under the contract will not leak for a period of, say, five years, and that if it does leak within this period, the contractor will make repairs at no additional cost to the owner so that the roof will not leak. Unless the roof leaked for some reason for which the owner was directly or indirectly responsible, courts will interpret the requirements of the warranty strictly. The owner would not have to prove that the contractor was at fault or was negligent. The mere fact that the roof leaked is all that is necessary to establish the contractor’s liability for the necessary repairs.

Just how strictly express warranties can be enforced is illustrated by a 1988 case in which the Iowa Supreme Court affirmed a lower court’s award of foreseeable consequential damages suffered by the owner of a distillery due to a design/build contractor’s failure to meet the performance guarantees stated in the contract. The contract provided that the completed plant would be capable of producing 190,000 gallons of ethanol per month and in so doing would not consume more than 36,000 BTU of heat per gallon of ethanol produced. The completed plant never met the stated output and consumed more BTUs per gallon than stated, causing the owner to lose money. The plant eventually was closed. The damages awarded the owner included the operating losses suffered during the period of plant operation plus the difference between the initial cost of the completed plant and its greatly diminished salvage value.[1]

A special kind of strict liability that applies to construction contracting is liability to third parties for damage that results from the performance of ultrahazardous construction activities such as blasting or demolition work in urban environments or liability for any activity that causes damage to a property owner’s land (as distinct from damage to buildings or other improvements on the land). This particular type of liability is sometimes called absolute liability. The standard of care used in conducting the construction operations or the precautions taken to avoid damage are not taken into consideration. The only thing that matters is that the damage was caused by the construction activity. If it was, the contractor’s liability is absolute.

Conclusion

This chapter briefly examined the major participants in the construction industry in the United States today, the rules by which they interact with each other, and the different kinds of liability knowingly or unknowingly assumed by participants in the industry. The emphasis here is that the first and foremost source of the rules governing the interactions of participants is the contracts into which they voluntarily enter.

Succeeding chapters continue this emphasis on the importance of contracts. Chapter 2 discusses the elements required for contract formation from a construction industry perspective leading into privity of contract and other contract relationships. The following chapters deal with the more important details of the contracts most commonly used in the construction industry.

Questions and Problems

- What is common law? How have the customs and practices of the construction industry influenced its evolution?

- What are the seven main groups of participants in the construction industry? Who are typical members of each group?

- What are the seven major statutes—or groups of statutes, laws, or regulations—that were identified in this chapter? What is each intended to accomplish?

- What is a tort? Is tort law a part of the common law?

- Define and suggest possible examples of the following:

- Contract liability

- Tort liability

- Express terms or provisions

- Implied terms or provisions (sometimes called implied warranties)

- Statutory liability

- Strict liability

- Absolute liability

- Can certain contract liabilities also be strict liabilities? Can tort liabilities be strict liabilities? Can statutory liabilities be strict liabilities? Explain each of your answers.

- Consider the following factual situation: The parties to a construction contract were a contractor and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps). The work of the contract was to construct an earth levee embankment along a river from material borrowed from a designated borrow pit shown on the contract drawings. To provide a means for the contractor to haul the borrow material from the borrow pit to the levee site, the Corps had previously obtained a 50-foot-wide easement through a landowner’s property. The contract contained no provisions one way or the other concerning potential damage to the landowner’s property, only that the contractor would be allowed to haul earth over the 50-foot easement previously obtained by the Corps. During the course of the contract work, construction equipment leaked crankcase oil, and a large quantity of fuel oil was inadvertently spilled by the contractor on the land within the 50-foot easement. The landowner alleged serious damage to the land and sued the contractor for damages. On the basis of these facts. answer the following questions:

- If the damage to the land could be proved and you were the contractor, would you concentrate your legal efforts in attempting to convince the court that you had no liability or in seeking to prove that the extent of the actual damage was small? Explain your answer.

- If the contractor had decided to contest the liability issue and the court ruled in favor of the landowner, what kind of liability would be involved: contract, tort, or statutory? Explain your answer.

- If liability was found to exist in (b), would it flow from violation of some express provision of the contract or statutory law or from violation of an established principle founded in the common law? Explain your answer.

- Consider these two situations:

Situation A

A construction contract contains a provision that the contractor must guarantee that a sewer system to be installed will not be subject to groundwater infiltration of over 500 gallons per day per inch diameter of pipe per mile. Upon completion of the installation, tests reveal infiltration of 12,500 gallons per day in an 18,000-foot run of six-inch pipe.

Situation BA contractor encounters rock in an urban area excavation and elects to loosen it by blasting. The advice of experts was obtained, and the blasting operations were conducted with great skill and care. However, cracking occurred in the plaster walls of several houses in the immediate vicinity of the work as a result of the blasting. Briefly discuss these two situations, stating whether either of them results in liability for the contractor and, if so, the type or kind of liability involved.

- Farm Fuel Products Corp. v. Grain Processing Corp., 429 N.W.2d 153 (Iowa 1988). ↵