9 Assessing Agricultural Education

Tiffany Drape

Setting the Stage

The end of the unit is nearly here, and we must provide progress reporting. A stack of papers sits on our desk, more documents are on our computer, and the wall is lined with projects we’ve had our learners working on. We think, “Don’t forget all of the SAE projects that are off school grounds and CDE contest results.” Immediate feelings of dread and being overwhelmed, not knowing where to start, and wondering how to even grade all of this overcome us. “Forget it, everyone gets an A,” we think. The easy way seems like the path of least resistance so we can prepare for the next day and leave school at a reasonable hour. But we know our building principal will be observing us and asking us to provide examples of learner work, lesson plans, and how they were assessed so they can track our progress and report to the School Board and accrediting bodies. We go down the hall and ask another teacher what they do and how they grade. They email some rubrics. We scour the internet for assessments that are like the content we’ve been teaching hoping to find some fast help.

I can vividly recall this scenario my first year of teaching. No one taught me how to manage all the responsibilities I’d be tasked with, let alone how to then manage assessment, progress reports, and Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) accommodations, and then do a good job of reporting it to provide evidence of scholarly achievement. It was a watershed moment for me, and it will be for you too. Everything is new and unfamiliar, everything feels immediate, but much of it won’t lead to providing evidence of assessment.

Objectives

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce our readers to assessing agricultural education. More specifically, the objectives are to:

- Briefly review testing and assessment in the United States.

- Explore the use of formative assessment as a tool to evaluate agricultural education to support its importance in secondary education.

- Investigate backward design as one way to provide evidence as a form of assessment.

Introduction

Understanding that every program is different and agricultural education is not a static program across states, regions, territories, or countries, this chapter aims to help us understand what assessment is, what counts as evidence, who determines this, and how we can use these to provide evidence of learning and career skill development for twenty-first century agricultural education. What I propose is formative, longer-term assessment, not the once-per-year test that our education system is currently built on. To provide evidence to our stakeholders, community members, and other folks who will want to know how we’re training learners, formative assessment can drive home the importance and perhaps even necessity of agriculture education and Career and Technical Education (CTE) as an integral part of public education.

Overview of Assessing Agricultural Education

This overview provides a brief history of education standards at the state and national levels. Standards Based Education (SBE) rose to become mainstream in the 1970s and 1980s. Before this, most jobs in the United States required only an eighth-grade proficiency. With the rise of international trade and outsourcing of labor and manufacturing, the United States soon realized that it needed employees with higher-level skills and an eighth-grade education was no longer sufficient for these jobs.

Governors took initiative with drafting and implementing standards for their respective states and territories. By 1989, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics published “Curriculum and Evaluation Standards for School Mathematics.” In 1990, President Bush announced a set of education goals for the nation and the governors followed suit, forming a task force to monitor each state’s goals. As the 1990s progressed, all but one of the states and territories developed their own unique statewide standards, and most either bought off-the-shelf tests for statewide use or created their own. Most states and territories worked with commercial testing companies to produce custom tests, frequently of much the same design as the most popular off-the-shelf tests. The tests satisfied the need of the accountability wing of the standards movement for an instrument that could be used to hold teachers accountable. In doing so, the tests fell far short of the kind of assessment tool that would provide incentives that fostered problem solving and critical thinking in the schools.

Note that standards vary on tribal, Indigenous, and other sovereign lands. The Bureau of Indian Education works as part of the US government to provide direction and management of all education functions, including the formation of policies and procedures, the supervision of all program activities, and the approval of the expenditure of funds appropriated for education on Indigenous lands. This encompasses 183 schools among 64 reservations in 23 states and 26 tribal colleges and universities.

As the twentieth century ended, the accountability movement came to dominate the standards movement in most states. States began building out comparison charts showing how schools compared to one another and to the state standards on the state tests. School districts everywhere began to find themselves under pressure to improve student performance based on the tests. This pressure was, of course, passed down to the schools and teachers. Many of the state tests were narrowly focused on facts and skills, rather than on a real understanding of the subject, critical thinking, and problem solving. Because of this, teachers focused almost wholly on test preparation and narrowed the curriculum. This depressed the achievement of many learners who would have achieved at higher levels if there had been no accountability system. Many teachers felt that the new tests and the accountability system that went with them were destroying effective teaching.

How did this narrow the curriculum?

The National Research Council (2011) concluded that the emphasis on testing yielded little learning progress but caused significant harm to both learners and teachers. Teachers who succumbed to the pressure were forced to only cover what would appear on the test, teach in less inclusive ways, and conform their teaching methods to the multiple-choice format that many tests are designed for, and many were driven out of the profession.

Narrowing the curriculum undermined student engagement, discouraged inclusive education, and harmed learners from low-income and underrepresented minority (URM) backgrounds, English language learners, and learners with disabilities. Children from white, middle- and upper-income backgrounds were more likely to be placed in “gifted and talented” or college preparatory programs where they are challenged to read, explore, investigate, think and progress rapidly while their less privileged peers often lagged even farther behind.

Missing from this standards-based model, but part of other educational assessment and curriculum delivery models, were: (1) high standards that incorporate a “thinking curriculum,” like critical thinking; (2) assessments that teachers would like to teach to; (3) authority for the school principals and others who bear the burden of accountability to enact changes when necessary; (4) clear curriculum frameworks that would make it possible to build fully aligned instructional systems; and (5) investments in the tools and training the people would need to do the job.

In 2002, No Child Left Behind (NCLB) expanded, booming the high-stakes testing industry and becoming one of the major drivers in school performance determination. The impact of this law proved to be wide reaching, affecting every single school in some way. One of the major aspects of NCLB was the provision that required states adopt a system of accountability whereby learners, teachers, administrators, and schools are evaluated annually based on learners’ standardized test performance and that consequences follow when student scores are low or annual gains in school achievement are not made.

Negative consequences include narrowing the curriculum, teaching to the test, pushing learners out of school, driving teachers out of the profession, and undermining student engagement and school climate.

Learners from low-income and minority-group backgrounds, English language learners, and learners with disabilities, are more likely to be denied diplomas, retained in grade, placed in a lower track, or unnecessarily put in remedial education programs. They are more likely to receive a “dumbed-down” curriculum, based heavily on rote drill and test practice. This ensures they will fall further and further behind their peers. Many drop out, some ending up in the “school-to-prison pipeline.” On the other hand, children from white, middle- and upper-income backgrounds are more likely to be placed in “gifted and talented” or college preparatory programs where they are challenged to read, explore, investigate, think, and progress rapidly.

As a result, teachers and administrators feel enormous pressure to ensure that test scores consistently rise. Schools narrow and manipulate the curriculum to match the test, while teachers tend to cover only what is likely to be on the next exam. Methods of teaching conform to the multiple-choice format. Education increasingly resembles test prep. It is easy to see why this could happen in low-scoring districts. But some high-scoring schools and districts, striving to keep their top rank, also succumb. The pressure is so great that a growing number of administrators and teachers have engaged in various kinds of cheating to boost scores.

High-Stakes Testing

We can’t talk about learning standards without talking about high-stakes testing. Since its inception, it’s grown into a billion-dollar business. SAT, ACT, LSAT, GRE, and MCAT are a few of the acronyms we might be familiar with and perhaps have even had to take yourself. High-stakes testing has arguments both for and against them and the debates about costs, equity, and access continue. Whether we like them or not, our learners will have to take them or have taken them already. Understanding their role in public education and how we can use them as part of our agriculture programming can be helpful in providing evidence to our stakeholders in our school district.

These tests are not only used to assess student aptitude and achievements, but also to inform how funding is funneled, assess curriculum and instruction, and help make predictions about how successful a student will be after they graduate. Most folks never take the time to investigate how these tests came to be adopted en masse or if they are in fact valid and reliable tools at determining aptitude and achievement of learners or a school. We know that high-stakes testing is not the panacea but the education system we may work in will use these tests as input to make decisions each year.

We know that high-stakes testing affects things like a student passing to the next grade level and choosing a school or moving within a district and schools being able to receive funding for special services and IEP accommodations. The list is endless. In some schools, learners will take as many as 113 standardized high-stakes test from K-12.

Most Americans trust that these tests were crafted with the utmost care and accurately report on student achievement in a reliable and valid way. For the most part, these tests have been integrated into the current education system. Most citizens don’t question the information generated from these tests and how they are used.

Opportunity for Agricultural Education

This is the opportunity for agricultural education to lead on the reimagining of what the future of standards might look like. Compulsory education is one of the longest running experiments in our country and agricultural education should continue to be part of this basic education that school-aged children deserve. Creating compelling, reliable methods to formatively assess learners is one way to ensure that the importance of agricultural education does not get lost. We can teach learners how to critically think, problem solve, and provide long-term evidence of learning. Agricultural education can adapt with these changes. Many agricultural education teachers are already dual certified, offer college level courses to empower learners with inclusive education, and can be asked to teach one or more classes outside of their certification area, depending on their state/territory certification policies. With the wide variety of agricultural education classes, dual enrollment, college credit, and the integration of Future Farmers of America (FFA) and Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE), agricultural education has expanded the narrow curriculum in a manageable and actionable way. Now the field needs to prove why it works and model how it can work while working with and respecting NCLB, SBE, and high-stakes testing.

Agricultural education and CTE offer valuable skills, but they can be hard to justify without evidence. Not all administrators view evidence the same way. A ribbon with a county fair SAE project or win at a Leadership Development Event (LDE) is not always considered assessment. As budgets shrink, test scores continue to drive funding, and resources continue to be stretched, agricultural education must take advantage of the work it’s currently doing to create the program we envision. Whether we’re a veteran teacher in that school or it’s our first job, the goal of assessment should be to leave it better than we found it. What “better” means is up for interpretation.

In every education setting we’ll work in, both formal and informal, there will always be the trend or the popular thing at the time. Word walls, learning objectives, book clubs, and a host of other district mandated teaching strategies will be employed by administrators, and we’ll be expected to conform to these things. How can we design assessment to endure long past the newest trend? How do we incorporate the new trend without feeling like we need to start from scratch?

We’re Not Grading, We’re Collecting Evidence

Let’s reframe our thinking first. We’re not grading assignments. We’re collecting evidence to determine student progress and pointing them toward their next steps. The mental switch alone will provide us the time, space, and permission to figure out if we want to prioritize assessment. When we think of it as providing feedback and pointing in the next direction, it no longer turns into this “thing we have to do” but will hopefully make it the thing we need to inform the learners, ourselves, and other interested stakeholders. We don’t have to collect all the evidence by ourselves either. Expanding the relationship with our learners to engage them in their own progress through keeping records, actively reflecting, exhibiting incremental progress, and sharing those things with us will help take some of the burden from us. Providing feedback is not a one-way conversation, it should be reciprocal.

What Counts as Evidence?

Almost anything can count as evidence. Let’s start with existing evidence. New teachers rarely look at what already exists regarding assessment and with learners who may have taken prior coursework in that program. Other existing data can be student records, IEP plans, and prior results from FFA and SAE work. This can serve as baseline evidence and gives us and the learners a place to begin identifying what milestones or progress they can work toward.

Some say that any assessment framework and any assessment model that tracks progress against individual learning intentions and targets counts as evidence. This operates under the assumption that these models and frameworks exist, which they may not be the case during our first year or three of teaching. Evidence comes from two principal sources: direct observation and the examination of artifacts.

If we need a nonexhaustive list of what could count as evidence:

- Images, still and moving

- Audio evidence

- Interviews, in audio or transcribed form

- Group discussions, in audio or transcribed form (check school policies on recording)

- Documents

- Observations

- Field notes

- Data from think-aloud protocols

- Anecdotes

- Answers to questionnaires

- Record books

- Results from CDE’s or other leadership events

We also need to consider what counts as evidence for teacher evaluations. The two are intimately linked. We may want to inquire about this with our mentors, colleagues, and building principal to help us understand the evaluation itself and what’s being evaluated. The task then becomes figuring out what to do with it, how to assess it, and then how to package and communicate it to the various stakeholder groups.

Formative and Summative Assessment

While there are many kinds of evidence from the list above, how we organize and report evidence falls in one of two camps: formative or summative assessment. We can put a play on words to help us remember the difference between formative and summative. Summative assessment refers to a summary at the end. Summative assessment, which is what high-stakes testing is, is the one time, one test that determines a multitude of aspects of a student, their teachers, their school, and their performance across that class or grade.

Formative refers to assessment that is formed along the way or incrementally. Instead of one test to determine the success or failure of a student, I’m proposing we take a formative approach to assessment.

Here’s why: Agricultural education is an evolving industry, and an evolving curriculum goes with it. The curriculum is always adapting, improving, learning new things that add to our collective education. As the agriculture industry changes, we must adapt as well. Formative assessment gives us the autonomy to adapt without losing the rigor and evidence-based collection.

What would happen if we could collect that evidence incrementally instead of waiting until the end of the marking period or term and then panicking because grades are due? As we look back at the pile of “work” or evidence, many teachers look at it and say or think “What did I even do with these kids the past X number of weeks?” Some are more organized, but new or young teachers are often so overwhelmed by everything that they forget that the evidence they provide informs decisions about their learners, their own employment, the school, and the community. There are so many aspects to be mindful of when starting out, assessment often falls by the wayside until it doesn’t, and the principal or team leader needs that evidence for reporting.

We may be asking ourselves several questions: How do we do this? Collect intentional evidence to provide formative evidence?

Let’s think about it backward. At the end, what do we want our learners to know, or what skills should they have acquired, and what evidence do we want to be able to provide to prove incremental progress?

Learning Confirmation

Let’s use this sample objective to help guide us:

- Goal for the learner: Learners will be more proficient public speakers.

- Objectives: Understand, describe, and report on agricultural issues.

- Task: Apply information to design and develop a prepared public speech for a contest.

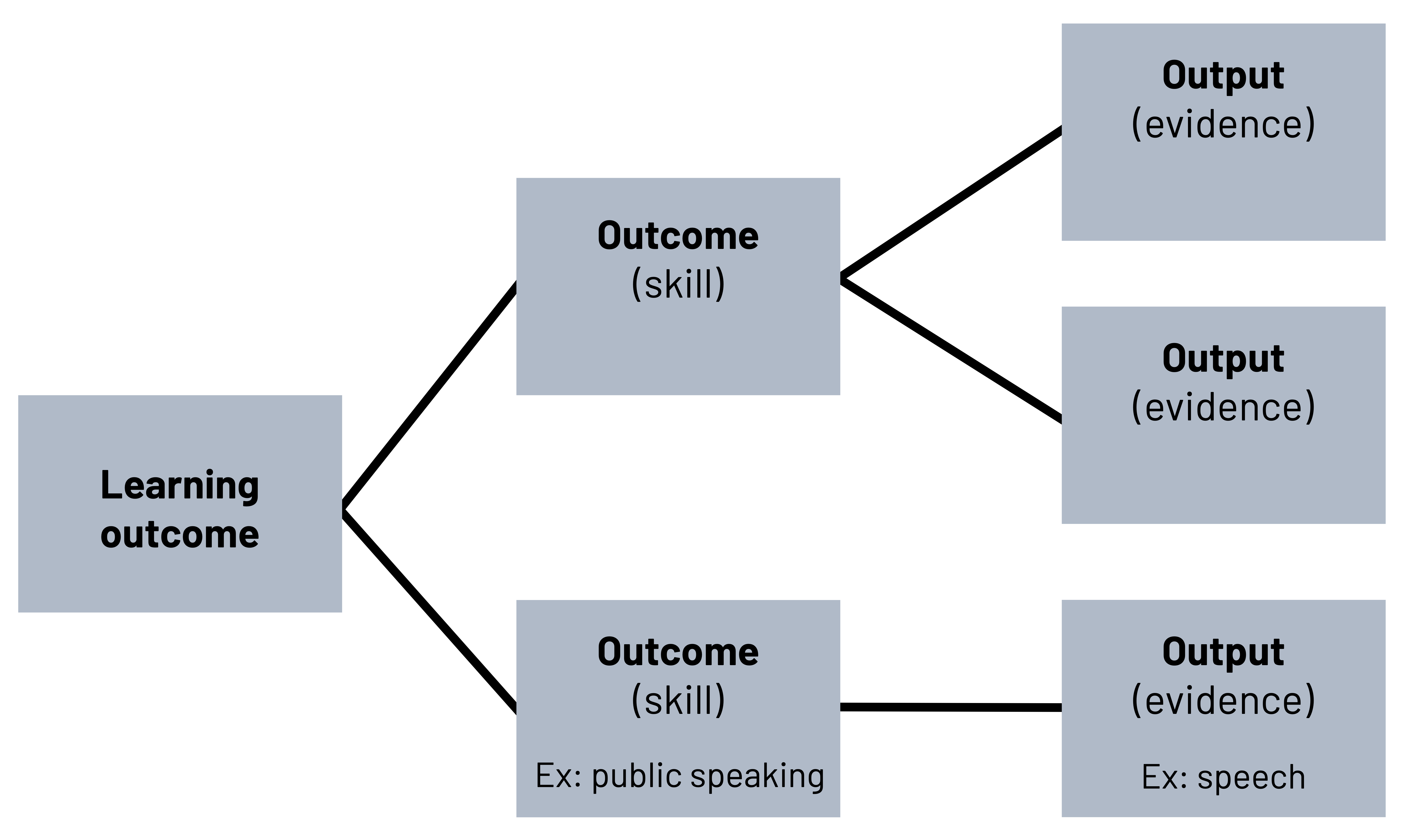

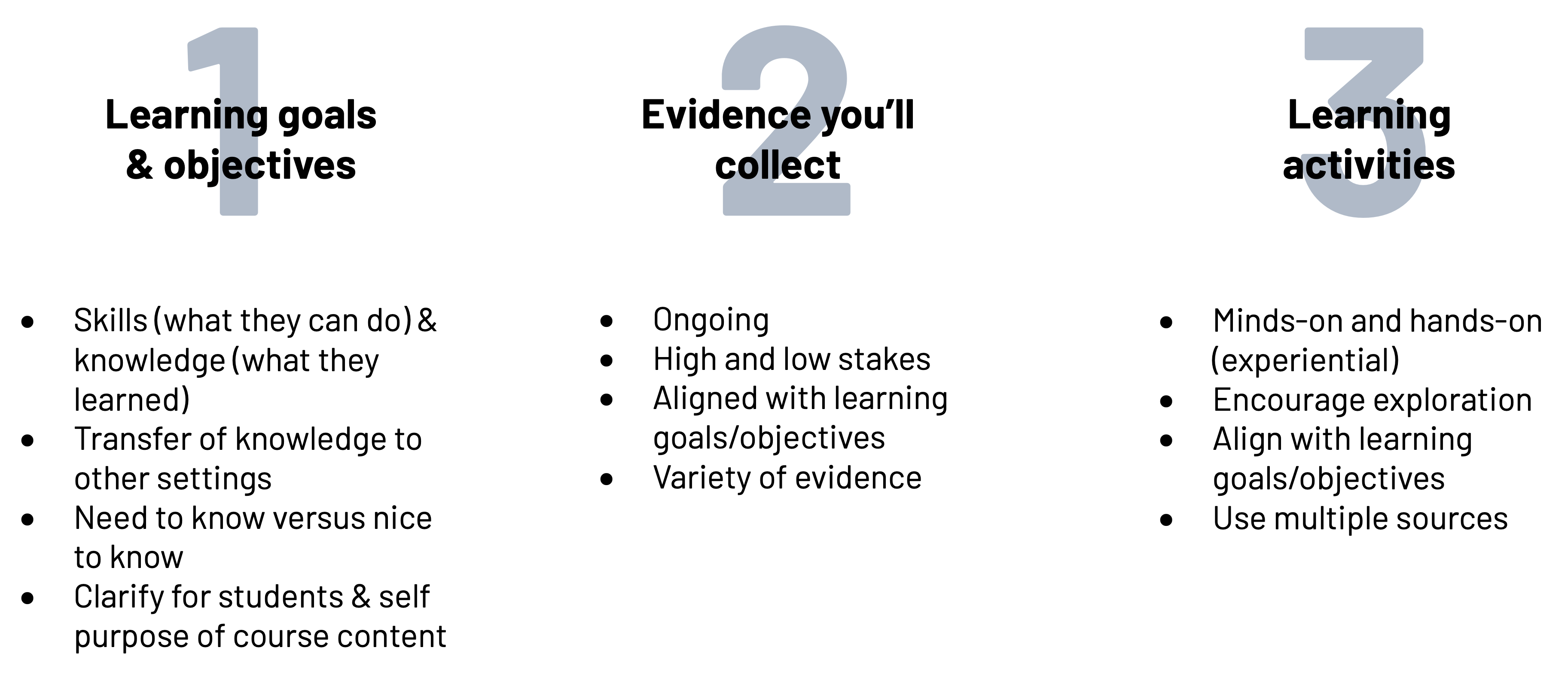

Backward Design: A Primer

What if we designed our formative assessments using a backward design? Thinking about what we want the student to understand, explain, and expand at the end of that course can help us work from the end back to day one (figure 9.1). Along the way, we can collect the incremental pieces that will account for the evidence we’ll use in the formative assessment of the learners. Since evidence is broadly defined, we can move away from that “traditional test” we’ve been taught and expand what we might want to collect that counts as evidence. Instead of one recording of the student presenting their speech at the end of the course, recording at several points during the class will create a trail of evidence that we can use to assess student progress and with stakeholders to show incremental progress over time. We may find that sometimes those “traditional tests” are still useful, but they’re not the only or best way to provide evidence of student progress toward that objective at the end of the course. What other pieces of evidence could we collect to provide concrete progress in our learners throughout the course?

We can start planning with the final outcome in mind to guide the class, account for changes along the way, and offer places for us as the teacher to make adjustments. We can ask ourselves several questions to help frame our thinking. Start with the “need to know” questions first: What do learners need to understand at the end of the unit or course? What skills will they acquire through completing the unit or course? At what points will feedback be important to give so learners can keep moving forward? How are we ensuring this is inclusive and will accommodate learners who may need more time to grasp concepts or have other needs?

Move onto what might be “nice to know” questions: What might be nice to include if we have space? What can be removed if something happens that hinders the progress?

Finally, “what do we need” questions: What do we need to learn to teach our learners? What resources do we need to teach the content? Where can we find the information and resources we’ll need?

Laying the answers out on note cards or organizing using a visual aid can help refine and prioritize what we might teach. As an example, if lessons are taking longer than anticipated, we can go back to our design and decide which activities and pieces of evidence will provide the information we need and what can be changed, edited, or cut. It will not change the goals or objectives of the class; it will only adjust and adapt the formative evidence we collect along the way. (See figure 9.2.)

When we think about the end first, it can help us make decisions about what we can do, what we have time for, and identify points along the way where formative evidence should be collected. This is also something we can provide for our own teacher evaluations with specific points for the supervisor that can be used to gauge our progress and set our own incremental goals as an educator.

Applying the Content

Questions to ask:

- What do we want learners to understand at the end of the unit/course? What evidence do we need to exhibit that proficiency or skill?

- Next, what steps or skills do learners need to learn to meet objective one?

- What pieces of evidence from class activities do we need to collect to provide incremental progress to meet objective one?

Deliberately asking ourselves these questions can help us distill what’s important for a student to be competent in versus what’s less important. It can then inform our decision-making process on what we’ll count as evidence, at what point(s) it will be collected, and how it will be assessed. In short:

- Identify the desired results (big ideas and skills).

- Determine acceptable levels of evidence that support that the desired results have occurred (culminating assessment tasks).

- Design activities that will make desired results happen (learning events).

Secondary questions after we’ve made this initial list or document could include how much time these activities take, what will count as evidence, what supplies/materials we need, and what considerations exist for students with IEP/special needs.

Assessing the Learning Activities

Let’s be honest, there is no right or perfect way. Looking for a panacea will not be found. What we’re sharing are some basic guiding tenants to begin thinking about, practicing, and implementing to help us begin our teaching career. Our teaching style, the community we work in, and the learners we serve are a few components that will inform how we assess learners. First know that we can (and should consider) using existing rubrics to assess learner work. Returning to the example of a public speaking course, the MANRRS Public Speaking Contest, National FFA Public Speaking Contest, or any related guidelines can be used and adapted to fit our student’s needs. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel and we can make changes to adapt preexisting models to our learners and their work. We can use the same rubric over the life of the public speaking class or unit and document student progress over time. This will show areas of improvement for both us and the learner and provide a long-term evidence trail over the life of the class or unit.

Formative assessment not only means collecting incremental evidence as a process over time but giving specific feedback to learners that is then turned into student action, assessing regularly, sometimes even daily, and taking the data to modify the learning plan and instruction for the learners. Rapid feedback loops must be incorporated to offer learners regular feedback. Feedback can be given in multiple ways and doesn’t have to be long. It could be as simple as figuring out how to get a learner to stop using filler words (e.g., um, like) and can be documented through recordings that the student then reviews and works to alleviate their use. Having those recordings will provide incremental evidence that the student did improve their public speaking skills.

Formative assessment allows for the student to participate as well. When we look for progress over time, the learner can actively participate in deciding what they deem as progress. Using fewer filler words, being able to reflect on class activities, and making adjustments should involve the learners so they can not only participate in their own learning, but also participate in their progress to achieve that learning.

- What would our backward design look like using the example of the public speaking course?

- What changes or edits are needed?

- What pieces of evidence would we collect to show as evidence?

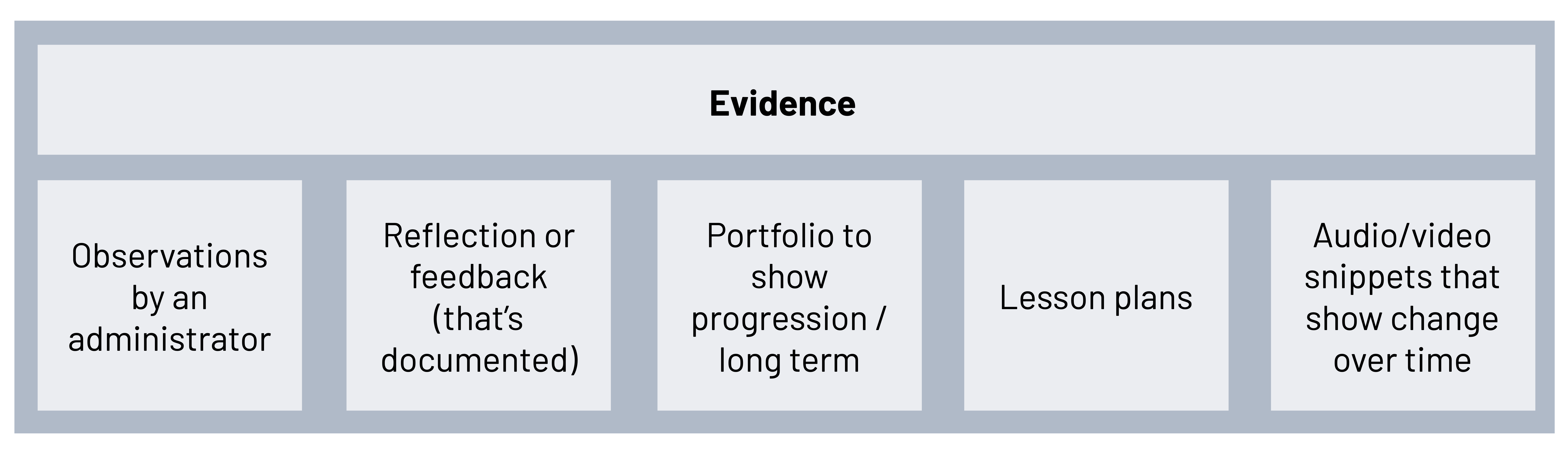

Using Formative Assessment for Teacher Evaluations

We’ll collect a lot of small pieces of incremental evidence from our learners. We may have audio recordings of speeches, drafts of speeches with edits, and perhaps even a result from the CDE contest with a picture of that learner presenting in the contest. Our learners can help with this as well, providing drafts, reflective feedback, and organizing any of the evidence. All these together can tell a compelling story that can be used to evaluate our progress as a teacher.

It’s one thing to be able to report that we had a successful student at the contest, but if our class had more than one student, we should consider including their evidence since it likely showed improvement from day one to the end of the class. That collection of audio files, speech drafts, and self-reported feedback from the learners puts together a compelling set of evidence that can speak to our effectiveness as an educator and provide data for our evaluations (see figure 9.3).

Peer review/exchange, a type of assessment: Take this existing curriculum and work through it. Does it meet the learning objectives set forth? Please provide at least two pieces of evidence in the curriculum that meet those objectives and identify them. Exchange with your peer(s) and work through their work. What agreement did you have? Where did you find different evidence to support the learning objectives? In what ways is curriculum subjective? When we interpret, what should we be mindful of when working with learners? What should we be mindful of when working with administrators and other stakeholders?

Reflective Questions

In Summation and Reflection

We can only handle so much during our first year of teaching. Instead of trying to “do it all,” decide on one or two places to begin evaluating and amending the assessment plan. It will take practice and multiple iterations. We’ll learn as much, if not more, than our learners.

If we go back to our introduction of the teacher with piles of work but no way to assess, what might they do to triage the situation? Since this could be us soon, know that it is common, it takes practice, and it’s OK to ask for help and guidance.

What do we want agricultural education to look like in the future? What steps might we need to undertake related to assessment to get to that vision shared?

Glossary of Terms

- formative: Monitor student progress during the program or intervention

- summative: Evaluate student learning at the end of the program or intervention

Figure Descriptions

Figure 9.1: Flow chart. Learning outcome maps to an outcome or skill, such as public speaking. That outcome maps to an output ot evidence, such as a speech. Each learning outcome can have multiple outcomes. Each Outcome can have multiple outputs. Jump to figure 9.1.

Figure 9.2: Start with learning goals and objectives. This includes: (1) skills (what they can do) and knowledge (what they learned), (2) transfer of knowledge to other settings, (3) need to know versus nice to know, and (4) clarify for students and self purpose of course content. Then think about evidence you’ll collect. This includes: (1) ongoing, (2) high and low stakes, (3) aligned with learning goals/objectives, and (4) variety of evidence. Lastly, learning activities. This includes: (1) minds-on and hands-on (experiential), (2) encourage exploration, (3) align with learning goals/objectives, and (4) use multiple sources. Jump to figure 9.2.

Figure 9.3: Evidence includes: observations by an administrator, reflection or feedback that’s documented, portfolio to show progression or long term, lesson plans, and audio or video snippets that show change over time. Jump to figure 9.3.

Figure References

Figure 9.1: Backwards design. Kindred Grey. 2023. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.2: Backward course design. Kindred Grey. 2023. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.3: What counts as evidence for teacher evaluations. Kindred Grey. 2023. CC BY 4.0.

References

Danielson, C. (2007). Enhancing professional practice: A framework for teaching. ASCD.

Evidence for Learning. (2020, December 3). Evidence for Learning in action! https://www.evidenceforlearning.net/eflinaction/

The National Research Council. (2011). Incentives and test-based accountability in education. The National Academies Press.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2011. Incentives and Test-Based Accountability in Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12521

Nichols, S. L., & Berliner, D. C. (2007). Collateral damage: How high-stakes testing corrupts America’s schools. Harvard Education Press.

PBS. (2020, December 15). Americans Instrumental in Establishing Standardized Tests. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/sats/where/three.html

Stateuniversity.com. (2021, March 23). Standards Movement in American Education. https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2445/Standards-Movement-in-American-Education.html